CHAPTER 9

Information Governance and Records and Information Management Functions *

Records and information management (RIM) is a key impact area of information governance (IG)—so much so that in the records management (RM) space, IG is often thought of as synonymous with or a simple superset of RM. But IG is much more than that. We will delve into the details of RM here—a sort of crash course on how to identify and inventory records, conduct the necessary legal research, develop retention and disposition schedules, and more. Also, we identify the relationship and impact of IG on the RM function in an organization in this chapter.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines (business) records as “information created, received, and maintained as evidence and information by an organization or person, in pursuance of legal obligations or in the transaction of business.”1 It further defines RM as “[the] field of management responsible for the efficient and systematic control of the creation, receipt, maintenance, use, and disposition of records, including the processes for capturing and maintaining evidence of and information about business activities and transactions in the form of records.”2

RIM extends beyond RM (although the terms are often used interchangeably) to include information—that is, information such as e-mail, electronic documents, and reports. For this reason, RIM professionals must expand their reach and responsibilities to include policies for retention and disposition of all legally discoverable forms of information, RIM professionals today generally know that “everything is discoverable” and that includes e-mail, voicemail, social media posts, mobile data and documents held on portable devices, cloud storage and applications, and other enterprise data and information.

Electronic records management (ERM) has moved to the forefront of business issues with the increasing automation of business processes and the vast growth in the volume of electronic information that organizations create. These factors, coupled with expanded and tightened reporting laws and compliance regulations—most especially the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)—have made ERM essential for most enterprises, especially highly regulated and public ones.

ERM follows generally the same principles as traditional paper-based records management: There are classification and taxonomy needs to group and organize the records; and there are retention and disposition schedules to govern the length of time a record is kept and its ultimate disposition, which is usually destruction but can also include transfer (e.g., U.S. federal agency records sent to the national Archives and Records Administration for archiving and safekeeping) or long-term archiving. Yet e-records must be handled differently, and they contain more detailed data about their contents and characteristics, known as metadata. (For more detail on these topics see Appendix A.)

E-records are also subject to changes in information technology (IT) like file formats and protocols that may make them difficult to retrieve and view and therefore render them obsolete. These issues can be addressed through a sound ERM program that includes long-term digital preservation (LTDP) methods and technologies for digital records needed to be maintained 10 years or more.

ERM is primarily the organization, management, control, monitoring, and auditing of formal business records that exist in electronic form. But automated ERM systems also track paper-based and other physical records. So ERM goes beyond simply managing electronic records; it is the management of electronic records and the electronic management of nonelectronic records (e.g. paper, CD/DVDs, magnetic tape, audio-visual, and other physical records).

Most electronic records, or e-records, originally had an equivalent in paper form, such as memos (now e-mail), accounting documents (e.g. purchase orders, invoices), personnel documents (e.g. job applications, resumes, tax documents), contractual documents, line-of-business documents (e.g. loan applications, insurance claim forms, health records), and required regulatory documents (e.g. material safety data sheets). Before e-document and e-record software began to mature in the 1990s, many of these documents were first archived to microfilm or microform/microfiche.

Not all documents rise to the level of being declared a formal business record that needs to be retained; that definition depends on the specific regulatory and legal requirements imposed on the organization and the internal definitions and requirements the organization imposes on itself, through internal IG measures and business policies. IG is control of information to meet legal, regulatory, business and risk demands. In short, IG is security, control, and optimization of information.

ERM is a component of enterprise content management (ECM), just as document management, Web content management, digital asset management, enterprise report management, workflow, and several other technology sets are components. ECM encompasses all an organization's unstructured digital content, which means it excludes structured data (i.e. databases). ECM includes the vast majority—typically 80 to 90%—of an organization's overall information that must be governed and managed. Structured information held in databases makes up the remainder; however, due to its structured and consistent nature it is more easily managed.

ERM extends ECM to provide control and to manage records through their life cycle—from creation to destruction. ERM is used to complete the life cycle management of information, documents, and records.

ERM adds the functionality to complete the management of information and records by applying business rules to manage the maintenance, preservation, and disposition of records. Both ERM and ECM systems aid in locating and managing the records and information needed to conduct business efficiently, to comply with legal and regulatory requirements, and to effectively destroy (paper) and delete (digital) records that have met their retention policy time frame requirement, freeing up valuable physical and digital space and eliminating records that could be a liability if kept.

In the last few years, the term content services has been used to supplant and expand the definition of ECM, mostly to include cloud-based platforms that offer Software-as-a-Service tools to manage content. This renaming effort has been led by Gartner, and many see it as a necessary recharacterization of a market that has evolved.

Records Management Business Rationale

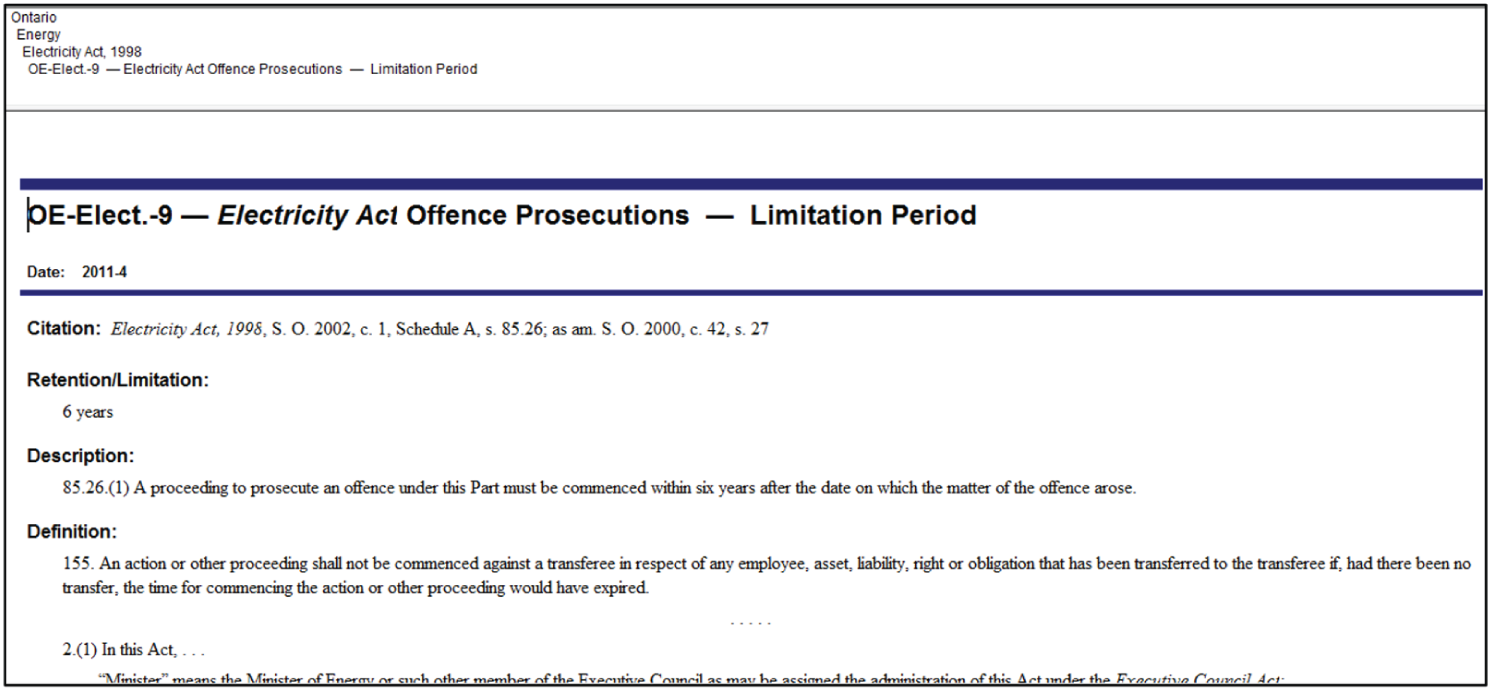

Historically, highly regulated industries, such as banking, energy, and pharmaceuticals, have had the greatest need to implement RM programs, due to their compliance and reporting requirements. However, over the past decade or so, increased regulation and changes to legal statutes and rules have made RM a business necessity for nearly every enterprise (beyond very small businesses).

Notable industry drivers fueling the growth of RM programs include:

- Increased government oversight and industry regulation. Government regulations that require enhanced reporting and accountability were early business drivers that fueled the implementation of formal RM programs. This is true at the federal and state or provincial level. In the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) created and enhanced standards of financial reporting and transparency for the boards and executive management of public corporations and accounting firms. It also addressed auditor independence and corporate governance concerns. SOX imposes fines or imprisonment penalties for noncompliance and requires that senior officers sign off on the veracity of financial statements. It states clearly that pertinent business records cannot be destroyed during litigation or compliance investigations. Since SOX was enacted, Japan, Australia, Germany, France, and India also have adopted stricter “SOX-like” governance and financial reporting standards. Newer legislation, such as the EU GDPR, and global privacy concerns have further driven the need for updated and expanded RM programs. This has given the RM profession a boost in visibility and energy.

- Changes in legal procedures and requirements during civil litigation. In 2006, the need to amend the US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) to contain specific rules for handling electronically generated evidence was addressed. The changes included processes and requirements for legal discovery of electronically stored information (ESI) during civil litigation. Today, e-mail is the leading form of evidence requested in civil trials. The changes to the US FRCP in 2006 and its update in 2015 had a pervasive impact on American enterprises and required them to gain control over their ESI and implement formal RM and electronic discovery (e-discovery) programs to meet new requirements. Although they have generally been ahead of the United States in their development and maturity of RM practices, Canadian, British, and Australian law is closely tracking that of the United States in legal discovery. The United States is a more litigious society, so this is not unexpected.

- IG awareness. IG, in sum, is the set of rules, policies, and business processes used to manage and control the totality of an organization's information. Monitoring technologies are required to enforce and audit IG compliance. Beginning with SOX in 2002 and continuing with the massive US FRCP changes in 2006 and 2015, along with the introduction of the far-reaching GDPR legislation, enterprises have been forced to become more IG aware and have spurred ramped up efforts to control, manage, and secure their information. A significant component of any IG program is implementing an RM program that specifies the retention periods and disposition (e.g. destruction, transfer, archive) of formal business records. This program, for instance, allows enterprises to destroy records once their required retention period (based on external regulations, legal requirements, and internal IG policies) has been met and allows them to legally destroy records with no negative impact or lingering liability. This practice, if consistently implemented, allows for the elimination of information that has low value to make room for new information that has higher business value.

- Business continuity concerns. In the face of real disasters, such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Hurricane Katrina, and Superstorm Sandy, executives now realize that disaster recovery and business resumption is something they must plan and prepare for. Disasters really happen, and businesses that are not well prepared really go under. The focus is on vital records, which are those most mission-critical records that are needed to resume operations in the event of a disaster, and managing those records is part of an overall RM program.

Why Is Records Management So Challenging?

With these changes in the business environment and in regulatory, legal, and IG influences comes increased attention to RM as a driver for corporate compliance. For most organizations, a lack of defined policies and the enormous and growing volumes of documents (e.g. e-mail messages) make implementing a formal RM program challenging and costly. Some reasons for this include:

- Changing and increasing regulations. Just when records and compliance managers have sorted through the compliance requirements of federal regulations, new ones at the state or provincial level are created or tightened down, and even those from other countries, such as GDPR, have had an impact.

- Maturing IG requirements within the organization. As senior managers become increasingly aware of the value of IG programs—the rules, policies, and processes that control and manage information—they promulgate more reporting and auditing requirements for the management of formal business records.

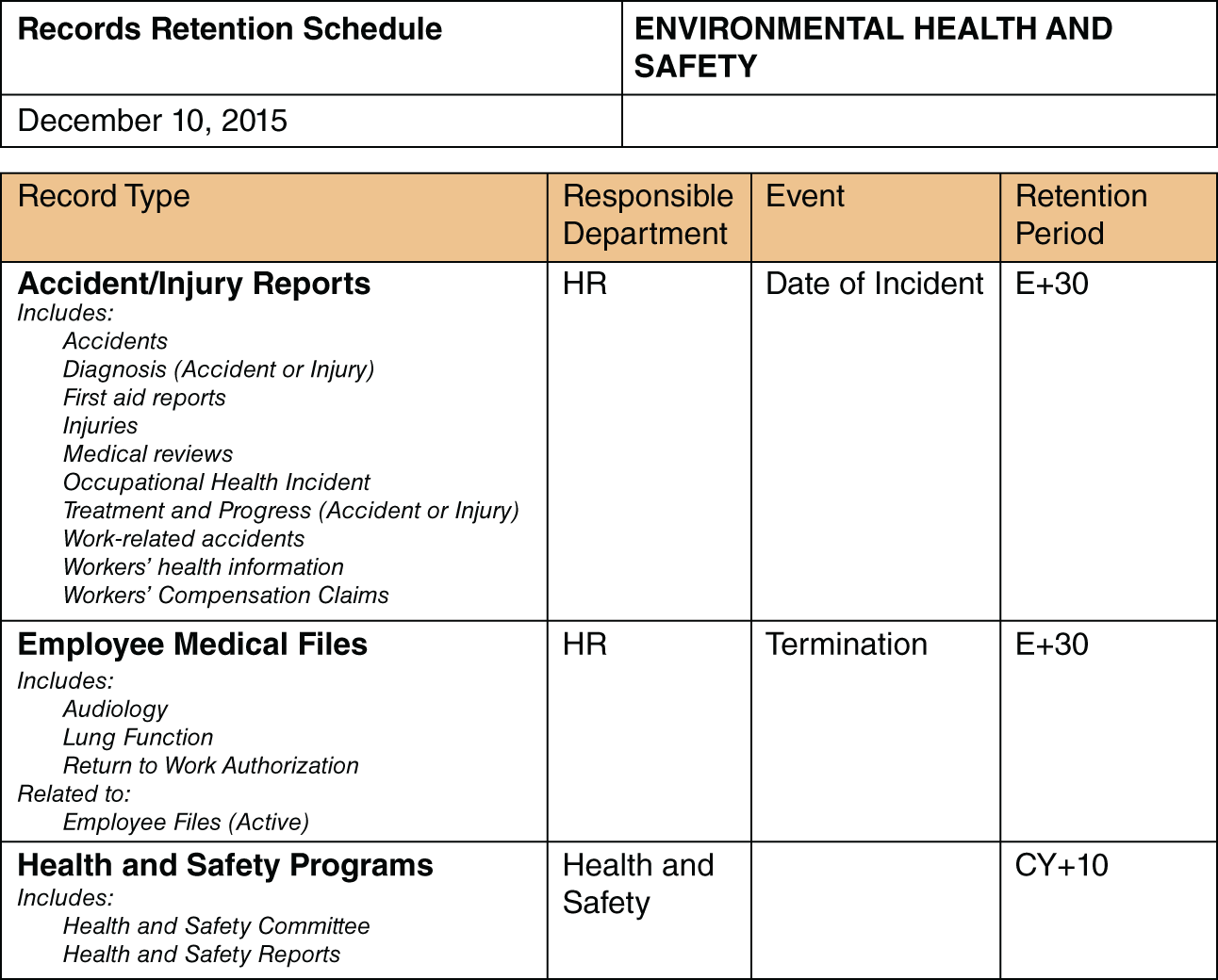

- Managing multiple retention and disposition schedules. Depending on the type of record, retention requirements vary, and they may vary for the same type of record based on state and federal regulations. Further, internal IG policies may extend retention periods and may fluctuate with management changes.3

- Compliance costs and requirements with limited staff. RM and compliance departments are notoriously understaffed, since they do not generate revenue. Departments responsible for executing and proving compliance with new and increasing regulatory requirements must do so expediently, often with only skeletal staffs. This leads to expensive outsourcing solutions or staff increases. The cost of compliance must be balanced with the risk of maintaining a minimum level of compliance.

- Changing information delivery platforms. With cloud computing, mobile computing, Web 2.0, social media, and other changes to information delivery and storage platforms, records and compliance managers must stay apprised of the latest IT trends and provide records on multiple platforms all while maintaining the security and integrity of organizational records.

- Security concerns. Protecting and preserving corporate records is of paramount importance, yet users must have reasonable access to official records to conduct everyday business. “Organizations are struggling to balance the need to provide accessibility to critical corporate information with the need to protect the integrity of corporate records.”4

- Dependence on the IT department or provider. Since tracking and auditing use of formal business records requires IT, and records and compliance departments typically are understaffed, those departments must rely on assistance from the IT department or outsourced IT provider—which often does not have the same perspective and priorities as the departments they serve.

- User assistance and compliance. Users often go their own way with regard to records, ignoring directives from records managers to stop storing shadow files of records on their desktop (for their own convenience) and inconsistently following directives to classify records as they are created. Getting users across a range of departments in the enterprise to adhere uniformly with records and compliance requirements is a daunting and unending task that requires constant attention and reinforcement. Increasingly, the solution is to automate the task of classification as much as possible using file analysis tools, often enabled with artificial intelligence (AI).

Benefits of Electronic Records Management

A number of business drivers and benefits combine to create a strong case for implementing an enterprise ERM program. Most are tactical, such as cost savings, time savings, and building space savings. But some drivers can be thought of as strategic, in that they proactively give the enterprise an advantage. One example may be the advantages gained in litigation by having more control and ready access to complete business records. This yields more accurate results and more time for corporate attorneys to develop strategies while the opposition is placing blunt legal holds on entire job functions and wading through reams of information, never knowing if it has found the complete set of records it needs. Another example is more complete and better information for managers to base decisions on. Further, applying the principles of infonomics may help organizations find new value or even to monetize information.

Implementing ERM represents a significant investment. An investment in ERM is an investment in business process automation and yields document control, document integrity/trustworthiness, and security benefits. The volume of records in organizations often exceeds employees’ ability to manage them. ERM systems do for the information age what the assembly line did for the industrial age. The cost/benefit justification for ERM is sometimes difficult to determine, although there are real labor and cost savings. Also, many of the benefits are intangible or difficult to calculate but help to justify the capital investment. There are many ways in which an organization can gain significant business benefits with ERM.

More detail on business benefits is provided in Chapter 7, but hard, calculable benefits (when compared to storing paper files) include office space savings, office supplies savings, cutting wasted search time, and reduced office automation costs (e.g. fewer printers, copiers, and automated filing cabinets).

In addition, implementing ERM will provide the organization with:

- Improved capabilities for enforcing IG policy over business documents and records.

- Increased working confidence in making searches, which should improve decision making.

- Improved knowledge worker productivity.

- Reduced risk of compliance actions or legal consequences.

- Improved records security.

- Improved ability to demonstrate legally defensible RM practices.

- More professional work environment.

Additional Intangible Benefits

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), a pioneer and leader in e-records implementation in the federal sector, lists some additional benefits of implementing ERM:

- To control the creation and growth of records. Despite decades of using various nonpaper storage media, the amount of paper in our offices continues to escalate. An effective records management program addresses both creation control (limits the generation of records or copies not required to operate the business) and records retention (a system for destroying useless records or retiring inactive records), thus stabilizing the growth of records in all formats.

- To assimilate new records management technologies. A good records management program provides an organization with the capability to assimilate new technologies and take advantage of their many benefits. Investments in new computer systems don't solve filing problems unless current manual recordkeeping systems are analyzed (and occasionally, overhauled) before automation is applied.

- To safeguard vital information. Every organization, public or private, needs a comprehensive program for protecting its vital records and information from catastrophe or disaster, because every organization is vulnerable to loss. Operated as part of the overall records management program, vital records programs preserve the integrity and confidentiality of the most important records and safeguard the vital information assets according to a “plan” to protect the records.

- To preserve the corporate memory. An organization's files contain its institutional memory, an irreplaceable asset that is often overlooked. Every business day, you create the records that could become background data for future management decisions and planning. These records document the activities of the agency that future scholars may use to research the workings of the Environmental Protection Agency.

- To foster professionalism in running the business. A business office with files askew, stacked on top of file cabinets and in boxes everywhere, creates a poor working environment. The perceptions of customers and the public, and “image” and “morale” of the staff, though hard to quantify in cost-benefit terms, may be among the best reasons to establish a good records management program.5

Thus, there are a variety of tangible and intangible benefits derived from ERM programs, and the business rationale that fits for your organization depends on its specific needs and business objectives.

Inventorying E-Records

According to the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), “In records management, an inventory is a descriptive listing of each record series or system, together with an indication of location and other pertinent data. It is not a list of each document or each folder but rather of each series or system”6 (emphasis added).

Conducting an inventory of electronic records is more challenging than performing a physical records inventory, but the purposes are the same: to ferret out RM problems and to use the inventory as the basis for developing the retention schedule. Some of the RM problems that may be uncovered

include inadequate documentation of official actions, improper applications of recordkeeping technology, deficient filing systems and maintenance practices, poor management of nonrecord materials, insufficient identification of vital records, and inadequate records security practices. When completed, the inventory should include all offices, all records, and all nonrecord materials. An inventory that is incomplete or haphazard can only result in an inadequate schedule and loss of control over records.7

The first step in gaining control over an organization's records and implementing IG measures to control and manage them is to complete an inventory of all groupings of business records, including electronic records,8 at the system or file series level.

The focus of this book is on e-records, and when it comes to e-records, NARA has a specific recommendation: inventory at the computer systems level. This differs from advice given by experts in the past.

The records inventory is the basis for developing a records retention schedule that spells out how long different types of records are to be held and how they will be archived or disposed of at the end of their life cycle. But first you must determine where business records reside, how they are stored, how many exist, and how they are used in the normal course of business.

There are a few things to keep in mind when approaching the e-records inventorying process:

- Those who create and work with the records themselves are the best source of information about how the records are used. They are your most critical resource in the inventorying process.

- RM is something that everyone wants done but no one wants to do (although everyone will have an opinion on how to do it).

- The people working in business units are touchy about their records. It will take some work to get them to trust a new RM approach.9

These knowledge workers are your best resource and can be your greatest allies or worst enemies when it comes to gathering accurate inventory data; developing a workable file plan; and keeping the records declaration, retention, and disposition process operating efficiently. A sound RM program will keep the records inventory accurate and up to date.

RM Intersection with Data Privacy Management

By Teresa Schoch

The tsunamic rise in electronic information and increasing complexity in information management10 has resulted in newly created or redefined roles tasked with creating order out of chaos. Information professionals attempt to control their domains in roles described as content management, knowledge management, e-discovery, data management, data security, records management, privacy management, and IG. Due to an increased focus on privacy rights in the EU, as well as in individual US states, potential enforcement actions have had an alarming impact on all of these roles, often causing intraorganizational conflict as enforced silos inhibit compliance with expanding and complex privacy laws.

Other than prohibitively expensive e-discovery disasters or unexpected regulatory audits leading to fines, in the past, there has been no real accountability in the United States as to how an organization maintains, organizes, creates, and/or disposes of its information. However, data breaches of private information, as well as the hacking of business and trade secrets, have become commonplace. 11 Corporations have scrambled to determine the what, where, when, and ownership of information that has been compromised, often racing against the clock to notify law enforcement and impacted individuals in time to avoid financial damages. C-level executives have lost their jobs over their company's mishandling of breaches.12 A court allowed a class action by credit card holders against Neiman Marcus,13 and the FTC acted against Wyndham Resorts for failure to protect the data of its customers.14 The potential for fines imposed by the FTC or state attorney generals based on state data-breach laws, damages in private lawsuits, or the untimely loss of highly placed executives increases the potential costs of a future breach. In addition, as reflected in the Neiman Marcus case, damage to a company's reputation due to the glaring scrutiny of its inadequate IG program serves to motivate others to remedy inadequate IG frameworks.15

Meanwhile, the EU has the right to fine US organizations collecting data on EU residents up to 20 million euros, or 4% of global sales, for the mishandling of personal data pursuant to the GDPR, which became effective on May 25, 2018. Records management is at the core of information management, since it is the gatekeeper to all information of ongoing value to the organization (a record is defined as information that has business value or meets regulatory or litigation requirements); it is even more obvious in privacy management now that private data being maintained is required to be held for a specified time in a specified manner. Personal data must be capable of easy access and any data maintained on a protected individual must be accurate. In addition, when private data no longer has business value, the risk of maintaining it becomes prohibitive and it must be deleted in a manner that ensures continued privacy protection. As records managers assess their own domains, they realize that many of the obligations created by new privacy laws can only be met if they understand the new laws’ effects on how they manage personal data pursuant to laws that impact their organization. Some erroneously assumed that privacy managers/attorneys/directors would expand their roles by learning the RIM world and addressing the changes required by privacy laws, but instead, they refer the details of maintaining privacy-related records to their records staff. While their willingness to delegate the legal duties of access, scheduling, deletion, and reliability of personal data is laudable, it creates new dynamics and an increased level of responsibility within the RIM framework that might not be thoroughly understood by the organization.

Since the GDPR has taken effect, many corporate attorneys have instructed the RIM staff to reassess records retention schedules based on the GDPR. Overworked professionals from all domains have developed plans to meet compliance requirements, often attempting to make the law fit into how they have always handled their duties in the past. As an example, the RIM “big bucket” approach, utilized to create records retention schedules for global records containing personal data of EU residents, could lead to fines in the millions. When an EU country requires employment records’ retention of 30 years, while another country requires disposal of the same record types three months after termination of employment, a default to a 30-year schedule for all EU employment-related data is simply an unsound practice. Likewise, deletion of all EU employment data three months after employment termination would leave an organization open to an inability to meet the legal obligations of other jurisdictions, and to the inability to defend the organization in the event of litigation. In this instance, each country needs to be addressed individually. If there is a legitimate basis for maintaining personal data (e.g. potential litigation relating to employment), the data can be maintained under GDPR solely for that purpose, even if there is a privacy-related requirement of a shorter retention period for that specific data. In these “conflict of laws” situations, the data maintained for the interim retention period based on legitimate business interests requires heightened security as well as restricted access. Retention schedules relating to records containing personal data have their own rules, often involving a conflict of laws, that require a new data-scheduling framework within the RIM environment.

In the RIM domain, managing information that contains personal data is an example where less is more. Less information makes it easier and faster to retrieve relevant information (in this case, personal data), costs less to maintain, and limits liability to those whose information is deleted as soon as it no longer has business value. Until recently, the decision to “keep it all” was based on an assessment of return on investment that considered the risks worth taking compared to the cost of ensuring compliance through the creation of a long-term IG roadmap. The lack of calculated routine disposition was defended as a strategic decision to maintain data for marketing or business planning using increasingly sophisticated analytical software.

However, attempting to meet GDPR requirements while maintaining large data pools or warehouses of information that have not been identified, much less classified (the unknown unknown), creates an extremely difficult environment for compliance. For companies that do business with European residents, enforcing defensible disposition has become a critical mission. While scheduling records disposition has become more complex under GDPR, meeting a defensibility standard relating to disposition has become easier.

Generally Accepted Recordkeeping Principles®

It may be useful to use a model or framework to guide your records inventorying efforts. Such frameworks could be the DIRKS (Designing and Implementing Recordkeeping Systems) used in Australia or the Generally Accepted Recordkeeping Principles® (or “the Principles”) that originated in the United States at ARMA International. The Principles are a “framework for managing records in a way that supports an organization's immediate and future regulatory, legal, risk mitigation, environmental, and operational requirements.”16 More detail can be found in Chapter 3.

Special attention should be given to creating an accountable, open inventorying process that can demonstrate integrity. The result of the inventory should help the organization adhere to records retention, disposition, availability, protection, and compliance aspects of the Principles.

The Generally Accepted Recordkeeping Principles were created with the assistance of ARMA International and legal and IT professionals who reviewed and distilled global best practice resources. These included the international records management standard ISO15489–1 from the American National Standards Institute and court case law. The principles were vetted through a public call-for-comment process involving the professional records information management … community.17

E-Records Inventory Challenges

If your organization has received a legal summons for e-records, and you do not have an accurate inventory, the organization is already in a compromising position: You do not know where the requested records might be, how many copies there might be, or the process and cost of producing them. Inventorying must be done sooner rather than later and proactively rather than reactively.

E-records present challenges beyond those of paper or microfilmed records due to their (electronic) nature:

- You cannot see or touch them without searching online, as opposed to simply thumbing through a filing cabinet or scrolling through a roll of microfilm.

- They are not sitting in a central file room but rather may be scattered about on servers, shared network drives, or on storage attached to mainframe or minicomputers.

- They have metadata attached to them that may distinguish very similar-looking records.

- Additional “shadow” copies of the e-records may exist, and it is difficult to determine the true or original copy.18

Records Inventory Purposes

The completed records inventory contributes toward the pursuit of an organization's IG objectives in a number of ways: It supports the ownership, management, and control of records; helps to organize and prepare for the discovery process in litigation; reduces exposure to business risk; and provides the foundation for a disaster recovery/business continuity plan.

Completing the records inventory offers at least eight additional benefits:

- It identifies records ownership and sharing relationships, both internal and external.

- It determines which records are physical, electronic, or a combination of both.

- It provides the basis for retention and disposition schedule development.

- It improves compliance capabilities.

- It supports training objectives for those handling records.

- It identifies vital and sensitive records needing added security and backup measures.

- It assesses the state of records storage, its quality and appropriateness.

- It supports the release of information for Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), Data Protection Act, and other mandated information release requirements for governmental agencies.19

With respect to e-records, the purpose of the records inventory should include the following objectives:

- Provide a survey of the existing electronic records situation.

- Locate and describe the organization's electronic record holdings.

- Identify obsolete electronic records.

- Determine storage needs for active and inactive electronic records.

- Identify vital and archival electronic records, indicating need for their ongoing care.

- Raise awareness within the organization of the importance of electronic records management.

- Lead to electronic recordkeeping improvements that increase efficiency.

- Lead to the development of a needs assessment for future actions.

- Provide the foundation of a written records management plan with a determination of priorities and stages of actions, assuring the continuing improvement of records management practices.20

Records Inventorying Steps

NARA's guidance on how to approach a records inventory applies to both physical and e-records.

The steps in the records inventory process are:

- Define the inventory's goals. While the main goal is gathering information for scheduling purposes, other goals may include preparing for conversion to other media, or identifying particular records management problems.

- Define the scope of the inventory; it should include all records and other materials.

- Obtain top management's support, preferably in the form of a directive, and keep management and staff informed at every stage of the inventory.

- Decide on the information to be collected (the elements of the inventory). Materials should be located, described, and evaluated in terms of use.

- Prepare an inventory form, or use an existing one.

- Decide who will conduct the inventory, and train them properly.

- Learn where the agency's [or business’] files are located, both physically and organizationally.

- Conduct the inventory.

- Verify and analyze the results.21

Goals of the Inventory Project

The goals of the inventorying project must be set and conveyed to all stakeholders. At a basic level, the primary goal can be simply to generate a complete inventory for compliance and reporting purposes. It may focus on a certain business area or functional group or on the enterprise as a whole. An enterprise approach requires segmenting the effort into smaller, logically sequenced work efforts, such as by business unit. Perhaps the organization has a handle on its paper and microfilmed records but e-records have been growing exponentially and spiraling out of control, without good policy guidelines or IG controls. So a complete inventory of records and e-records by system is needed, which may include e-records generated by application systems, residing in e-mail, created in office documents and spreadsheets, or other potential business records. This is a tactical approach that is limited in scope.

The goal of the inventorying process may be more ambitious: to lay the groundwork for the acquisition and implementation of an ERM system that will manage the retention, disposition, search, and retrieval of records. It requires more business process analysis and redesign, some rethinking of business classification schemes or file plans, and development of an enterprise-wide taxonomy. This redesign will allow for more sharing of information and records; faster, easier, and more complete retrievals; and a common language and approach for knowledge professionals across the enterprise to declare, capture, and retrieve business records.

The plan may be still much greater in scope and involve more challenging goals: That is, the inventorying of records may be the first step in the process of implementing an organization-wide IG program to manage and control information by rolling out ERM and IG systems and new processes; to improve litigation readiness and stand ready for e-discovery requests; and to demonstrate compliance adherence with business agility and confidence. Doing this involves an entire cultural shift in the organization and a long-term approach.

Whatever the business goals for the inventorying effort, they must be conveyed to all stakeholders, and that message must be reinforced periodically and consistently, and through multiple means. It must be clearly spelled out in communications and presented in meetings as the overarching goal that will help the organization meet its business objectives. The scope of the inventory must be appropriate for the business goals and objectives it targets.

Scoping the Inventory

“With senior-level support, the records manager must decide on the scope of the records inventory. A single inventory could not describe every electronic record in an organization; an appropriate scope might enumerate the records of a single program or division, several functional series across divisions, or records that fall within a certain time frame” [emphasis added].22 Most organizations have not deployed an enterprise-wide records management system, which makes the e-records inventorying process arduous and time-consuming. It is not easy to find where all the electronic records reside—they are scattered all over the place and on different media. But impending (and inevitable) litigation and compliance demands require that it be done. And, again, sooner has been proven to be better than later. Since courts have ruled that if lawsuits have been filed against your competitors over a certain (industry-specific) issue, your organization should anticipate and prepare for litigation—which means conducting records inventories and placing a litigation hold on documents that might be relevant. Simply doing nothing and waiting on a subpoena is an avoidable business risk.

A methodical, step-by-step approach must be taken—it is the only way to accomplish the task. A plan that divides up the inventorying tasks into smaller, accomplishable pieces is the only one that will work. It has been said, “How do you eat an elephant?” And the answer is “One bite at a time.” The inventorying process can be divided into segments, such as a business unit, division, or information system/application.

Management Support: Executive Sponsor

It is crucial to have management support to drive the inventory process to completion. There is no substitute for an executive sponsor. Asking employees to take time out for yet another survey or administrative task without having an executive sponsor will likely not work. Employees are more time-pressed than ever, and they will need a clear directive from above, along with an understanding of what role the inventorying process plays in achieving a business goal for the enterprise, if they are to take the time to properly participate and contribute meaningfully to the effort.

Information/Elements for Collection

During the inventory you should collect the following information at a minimum:

- What kind of record it is—contracts, financial reports, memoranda, and so on

- What department owns it

- What departments access it

- What application created the record (e-mail, MS Word, Acrobat PDF)

- Where it is stored, both physically (tape, server) and logically (network share, folder)

- Date created

- Date last changed

- Whether it is a vital record (mission-critical to the organization)

- Whether there are other forms of the record (for example, a document stored as a Word document, a PDF, and a paper copy) and which of them is considered the official record

Removable media should have a unique identifier and the inventory should include a list of records on the particular volume as well as the characteristics of the volume, for example, the brand, the recording format, the capacity and volume used, and the date of manufacture and date of last update.

IT Network Diagram

Laying out the overall topology of the IT infrastructure in the form of a network diagram is an exercise that is helpful in understanding where to target efforts and to map information flows. Data mapping is a crucial early step in compliance efforts, such as GDPR. Creating this map of the IT infrastructure is a crucial step in inventorying e-records. It graphically depicts how and where computers are connected to each other and the software operating environments of various applications that are in use. This high-level diagram does not need to include every device; rather, it should indicate each type of device and how it is used.

The IT staff usually has a network diagram that can be used as a reference; perhaps after some simplification it can be put into use as the underpinning for inventorying e-records. It does not need great detail, such as where network bridges and routers are located, but it should show which applications are utilizing the cloud or hosted applications to store and/or process documents and records.

In diagramming the IT infrastructure for purposes of the inventory, it is easiest to start in the central computer room where any mainframe or other centralized servers are located and then follow the connections out into the departments and business unit areas, where there may be multiple shared servers and drives supported a network of desktop personal computers or workstations.

SharePoint is a prevalent document and RM portal platform, and many organizations have SharePoint servers to house and process e-documents and records. Some utilities and tools may be available to assist in the inventorying process on SharePoint systems. This process has been made easier with the introduction of cloud-based SharePoint services.

Mobile devices (e.g. tablets, smartphones, and other portable devices) that are processing documents and records should also be represented. And any e-records residing in cloud storage should also be included.

Creating a Records Inventory Survey Form

The record inventory survey form must suit its purpose. Do not collect data that is irrelevant, but, in conducting the survey, be sure to collect all the needed data elements. You can use a standard form, but some customization is recommended. The sample records survey form in Figure 9.1 is wide-ranging yet succinct and has been used successfully in practice.

| Department Information |

|

|

|

| Record Requirements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| When an employee changes jobs/roles or is terminated? |

|

|

|

|

|

| □ Fiscal Year □ Calendar Year □ Other |

|

|

|

|

| Online? Near Line? Offline? On-site? Off-site? One location? Multiple locations? |

|

| Technology and Tools |

|

|

|

| Disposition |

|

|

|

|

| Records Holds |

|

|

|

Figure 9.1 Records Inventory Survey Form

Source: Charmaine Brooks, IMERGE Consulting, e-mail to author, March 20, 2012.

If conducting the e-records portion of the inventory, the sample form may be somewhat modified, as shown in Figure 9.2.

| Identifying Information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| System Inputs/Outputs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Record Requirements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| □ Fiscal Year □ Calendar □ Year Other _______________________________ |

|

|

|

|

| Online? Near line? Offline? On-site? Off-site? One location? Multiple locations? |

|

| Disposition |

|

|

|

|

| Records Holds |

|

|

|

Figure 9.2 Electronic Records Inventory Survey Form

Source: Adapted from www.archives.gov/records-mgmt/faqs/inventories.html and Charmaine Brooks, IMERGE Consulting.

Who Should Conduct the Inventory?

Typically, a RM project team is formed to conduct the survey, often assisted by resources outside of the business units. These may be RM and IT staff members, business analysts, members of the legal staff, outside specialized consultants, or a combination of these groups. The greater the cross-section from the organization, the better, and the more expertise brought to bear on the project, the more likely it will be completed thoroughly and on time.

Critical to the effort is that those conducting the inventory are trained in the survey methods and analysis, so that when challenging issues arise, they will have the resources and know-how to continue the effort and get the job done.

Determine Where Records Are Located

The inventory process is, in fact, a surveying process, and it involves going physically out into the units where the records are created, used, and stored. Mapping out where the records are geographically is a basic necessity. Which buildings are they located in? Which office locations? Computer rooms?

Also, the inventory team must look organizationally at where the records reside (i.e., determine which departments and business units to target and prioritize in the survey process).

Conduct the Inventory

Several approaches can be taken to conduct the inventory, including four basic methods:

- Distributing and collecting surveys

- Conducting in-person interviews

- Direct observation

- Software tools

Creating and distributing a survey form is traditional and proven way to collect e-records inventory data. This is a relatively fast and inexpensive way to gather the inventory data. The challenge is getting the surveys completed and completed in a consistent fashion. This is where a strong executive sponsor can assist. The sponsor can make the survey a priority and tie it to business objectives, making the survey completion compulsory. The survey is a good tool, and it can be used to cover more ground in the data collection process. If following up with interviews, the survey form is a good starting point; responses can be verified and clarified, and more detail can be gathered.

Some issues may not be entirely clear initially, so following up with scheduled in-person interviews can dig deeper into the business processes where formal records are create and used. A good approach is to have users walk you through their typical day and how they access, use, and create records—but be sure to interview managers too, as managers and users have differing needs and uses for records.

You will need some direction to conduct formal observation, likely from IT staff or business analysts familiar with the record-keeping systems and associated business processes. They will need to show you where business documents and records are created and stored. If there is an existing ERM system or other automated search and retrieval tools available, you may use them to speed the inventorying process.

When observing and inventorying e-records, starting in the server room and working outward toward the end user is a logical approach. Begin by enumerating the e-records created by enterprise software applications (such as accounting, enterprise resource planning, or customer relationship management systems), and work your way to the departmental or business unit applications, on to shared network servers, then finally out to individual desktop and laptop PCs and other mobile devices. With today's smartphones, this can be a tricky area, due to the variety of platforms, operating systems, and capabilities. In a bring-your-own-device environment, records should not be stored on personal devices, but if they must be, they should be protected with technologies like encryption or information rights management.

Explore any potential software tools that may be available for facilitating the inventorying of e-records. Some software vendors that provide document management or e-record management solutions offer inventorying tools.

There are always going to be thorny areas when attempting to inventory e-records to determine what files series exist in the organization. Mobile devices and removable media may contain business records. These must be identified and isolated, and any records on these media must be recorded for the inventory. Particularly troublesome are thumb or flash drives, which are compact yet can store 20 gigabytes of data or more. If your IG measures call for excluding these types of media, the ports they use can be blocked on PCs, tablets, smartphones, and other mobile computing devices using data loss prevention (DLP) technology. A sound IG program will consider the proper use of removable media and the potential impact on your RM program.23

The best approach for conducting the inventory is to combine the available inventorying methods, where possible. Begin by observing, distribute surveys, collect and analyze them, and then target key personnel for follow-up interviews and walk-throughs. Utilize whatever automated tools that are available along the way. This approach is the most complete. Bear in mind that the focus is not on individual electronic files but rather, the file series level for physical records and the file series or system level for e-records (preferably the latter).

Interviewing Programs/Service Staff

Interviews are a very good source of records inventory information. Talking with actual users will help the records lead or inventory team to better understand how documents and records are created and used in everyday operations. Users can also report why they are needed—an exercise that can uncover some obsolete or unnecessary processes and practices. This is helpful in determining where e-records reside and how they are grouped in records series or by system and ultimately, the proper length of their retention period and whether they should be archived or destroyed at the end of their useful life.

Since interviewing is a time-intensive task, it is crucial that some time is spent in determining the key people to interview: Interviews not only take your time but others’ as well, and the surest way to lose momentum on an inventorying project is to have stakeholders believe you are wasting their time.

You need to interview representatives from all functional areas and levels of the program or service, including:

- Managers

- Supervisors

- Professional/technical staff

- Clerical/support staff

The people who work with the records can best describe to you their use. They will likely know where the records came from, if copies exist, who needs the records, any computer systems that are used, how long the records are needed, and other important information that you need to know to schedule the records.

Selecting Interviewees

As stated earlier, it is wise to include a cross-section of staff, managers, and frontline employees to get a rounded view of how records are created and used. Managers have a different perspective and may not know how workers utilize electronic records in their everyday operations.

A good lens to use is to focus on those who make decisions based on information contained in the electronic records and to follow those decision-based processes through to completion, observing and interviewing at each level.

For example, an application is received (mail room logs date and time), checked (clerk checks the application for completeness and enters into a computer system), verified (clerk verifies that the information on the application is correct), and approved (supervisor makes the decision to accept the application). These staff members may only be looking at specific pieces of the record and making decisions on those pieces.

Interview Scheduling and Tips

One rule to consider is this: Be considerate of other people's work time. Since they are probably not getting compensated for participating in the records inventory, the time you take to interview them is time taken away from compensated tasks they are evaluated on. So, once the interviewees are identified, provide as much advance notice as possible, follow up to confirm appointments, and stay within the scheduled time. Interviews should be kept to 20 to 60 minutes. Most of all—never be late!

Before starting any interviews, be sure to restate the goals and objectives of the inventorying process and how the resulting output will benefit people in their jobs.

In some cases, it may be advisable to conduct interviews in small groups, not only to save time but also to generate a discussion of how records are created, used, and stored. Some new insights may be gained.

Try to schedule interviews that are as convenient as possible for participants. That means providing participants with questions in advance and holding the interviews as close to their work area as possible. Do not schedule interviews back to back with no time for a break between. You will need time to consolidate your thoughts and notes, and, at times, interviews may exceed their planned time if a particularly enlightening line of questioning takes place.

If you have some analysis from the initial collection of surveys, share that with the interviewees so they can validate or help clarify the preliminary results. Provide it in advance, so they have some time to think about it and discuss it with their peers.

Sample Interview Questionnaire

You'll need a guide to structure the interview process. A good starting point is the sample questions presented in the questionnaire shown in Figure 9.3. It is a useful tool that has been used successfully in actual records inventory projects.

| What is the mandate of the office? |

| What is the reporting structure of the department? |

| Who is the department liaison for the records inventory? |

| Are there any external agencies that impose guidelines, standards, or other requirements? |

| Is there a departmental records retention schedule? |

| Are there specific legislative requirements for creating or maintaining records? Please provide a copy. |

| What are the business considerations that drive recordkeeping? Regulatory requirements? Legal requirements? |

| Does the department have an existing records management policy? Guidelines? Procedures? |

| Please provide a copy. |

| Does the department provide guidance to employees on what records are to be created? |

| What is the current level of awareness of employees their responsibilities for records management? |

| How are nonrecords managed? |

| Does the department have a classification or file plans? |

| What are the business drivers for creating and maintaining records? |

| Where are records stored? On-site? Off-site? One location? Multiple locations? |

| Does the department have records in sizes other than letter (8½ × 11)? |

| What is the cutoff date for the records? |

| □ Fiscal Year □ Calendar □ Year Other |

| Are any tools used to track active records? Excel, Access, and so forth? |

| Does the department use imaging, document management, and so forth? |

| Is the department subject to audits? Internal? External? Who conducts the audits? |

| Are any records in the department confidential or sensitive? |

| Are there guidelines for destroying obsolete records? |

| What disposition methods are authorized or required? |

| How does disposition occur? Paper? Electronic? Other? |

| What extent does the department rely on each individual to destroy records? |

| □ Paper □ Electronic □ Other ____________________________________________ |

| What principles govern decisions for determining the scope of records that must be held or frozen for an audit or investigations? |

| How is the hold or freeze communicated to employees? |

Figure 9.3 Sample Interview Questionnaire

Source: Charmaine Brooks, IMERGE Consulting, e-mail to author, March 20, 2012.

Analyze and Verify the Results

Once collected, some follow-up will be required to verify and clarify responses. Often this can be done over the telephone. For particularly complex and important areas, a follow-up in person visit can clarify the responses and gather insights.

Once the inventory draft is completed, a good practice is to go out into the business units and/or system areas and verify what the findings of the survey are. Once presented with findings in black and white, key stakeholders may have additional insights that are relevant to consider before finalizing the report. Do not miss out on the opportunity to allow power users and other key parties to provide valuable input.

Be sure to tie the findings in the final report of the records inventory to the business goals that launched the effort. This helps to underscore the purpose and importance of the effort, and will help in getting that final signoff from the executive sponsor that states the project is complete and there is no more work to do.

Depending on the magnitude of the project, it may (and should) turn into a formal IG program that methodically manages records in a consistent fashion in accordance with internal governance guidelines and external compliance and legal demands.

Appraising the Value of Records

Part of the process of determining the retention and disposition schedule of records is to appraise their value. Records can have value in different ways, which affects retention decisions.

Records appraisal is an analysis of all records within an agency [or business] to determine their administrative, fiscal, historical, legal, or other archival value. The purpose of this process is to determine for how long, in what format, and under what conditions a record series ought to be preserved. Records appraisal is based upon the information contained in the records inventory. Records series shall be either preserved permanently or disposed of when no longer required for the current operations of an agency or department, depending upon:

- Historical value or the usefulness of the records for historical research, including records that show an agency [or business] origin, administrative development, and present organizational structure.

- Administrative value or the usefulness of the records for carrying on [a business or] an agency's current and future work, and to document the development and operation of that agency over time.

- Regulatory and statutory [value to meet] requirements.

- Legal value or the usefulness of the records to document and define legally enforceable rights or obligations of [business owners, shareholders, or a] government and/or citizens.

- Fiscal value or the usefulness of the records to the administration of [a business or] an agency's current financial obligations, and to document the development and operation of that agency over time.

- Other archival value as determined by the State [or corporate] Archivist.24 (Emphasis added.)

Ensuring Adoption and Compliance of RM Policy

The inventorying process in not a one-shot deal: It is useful only if the records inventory is kept up to date, so it should be reviewed, at least annually. A process should be put in place so that business unit or agency heads notify the RM head/lead if a new file series or system has been put in place and new records collections are created. There are emerging approaches that utilize file/content analytics tools to automate this process.

Following are some tips to help ensure that a records management program achieves its goals:

- Records management is everyone's role. The volume and diversity of business records, from e-mails to reports to tweets, means that the person who creates or receives a record is in the best [position] to classify it. Everyone in the organization needs to adopt the records management program.

- Don't micro-classify. Having hundreds, or possibly thousands, of records classification categories may seem like a logical way to organize the multitude of different records in a company. However, the average information worker, whose available resources are already under pressure, does not want to spend any more time than necessary classifying records. Having a few broad classifications makes the decision process simpler and faster.

- Talk the talk from the top on down. A culture of compliance starts at the top. Businesses should establish a senior-level steering committee comprised of executives from legal, compliance, and information technology (IT). A committee like this signals the company's commitment to compliant records management and ensures enterprise adoption.

- Walk the walk, consistently. For compliance to become second nature, it needs to be clearly communicated to everyone in the organization, and policies and procedures must be accessible. Training should be rigorous and easily available, and organizations may consider rewarding compliance through financial incentives, promotions and corporate-wide recognition.

- Measure the measurable. The ability to measure adherence to policy and adoption of procedures should be included in core business operations and audits. Conduct a compliance assessment, including a gap analysis, at least once a year, and prepare an action plan to close any identified holes.

The growth of information challenges a company's ability to use and store its records in a compliant and cost-effective manner. Contrary to current practices, the solution is not to hire more vendors or to adopt multiple technologies. The key to compliance is consistency, with a unified enterprise-wide approach for managing all records, regardless of their format or location.

Therefore a steady and consistent IG approach that includes controls, audits, and clear communication is key to maintaining an accurate and current records inventory.

Tracking Information Assets: Moving Toward an Information Asset Register

A relatively new concept in IG is the development of an Information Asset Register (IAR). An IAR is a sort of “general ledger of information assets” that lists all information assets, structured and unstructured, their lifecycle retention, privacy and security requirements, where they are housed, and even what hardware is used. Dennis Kessler, Data Governance Lead at the European Investment Bank states, “This asset-based approach to managing information helps to reveal:

- Which people or teams are responsible and accountable for maintaining the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information

- Which people/teams and systems can access information, and for what purposes—whether to create, update, or consume information

- How information flows and is used throughout the organization—which business processes and which decision-making points depend on which information

- Regulatory, compliance, and other obligations”25

Briton Reynold Leming has been developing IAR software for several years. He has created a comprehensive list of benefits that an IAR provides:26

- Understanding Relationships: A related series of records sharing the same purpose (an “asset collection,” if you will) might have a variety of constituent entities (“assets”) in different formats—for example, physical records, digital content, system data. Identifying these within an IAR, with a suitable narrative recorded, will enable an understanding of their relationships and purpose over time. This could include, for example, the “story” of document handling paper originals and resulting images within a document scanning process or the retirement and introduction of systems.27

Allied to this is tagging assets to a business classification scheme of the functions and activities of your organization. This allows the assets to be categorized to a vocabulary of business activity that is neutral to and more stable than organizational structures (which can change more often than what an organization actually does), provides a collated corporate view of assets maintained based upon their purpose (e.g. many departments will hold invoice, staff, policy, and contract records), and supports cross-cutting processes involving different teams. It also allows the consistent inheritance and application of business rules, such as retention policies.

- Security Classification: Assets can be classified within the IAR to an approved security classification/protective marking scheme, with current protective measures recorded, in order to identify if there are any risks relating to the handling of confidential personal or commercially sensitive information. You can assess that assets are handled, stored, transferred, and disposed of in an appropriate manner.

- Personal Data: Specifically, you can identify confidential personal information to ensure that data protection and privacy obligations are met.

The GDPR contains many obligations that require a thorough understanding of what personal data you process and how and why you do so. Many requirements for keeping records as a data controller for GDPR Article 30 can be supported by the information asset inventory. For example, the asset attributes can describe the purposes of the processing, the categories of data subjects and personal data, categories of recipients, envisaged time limits for erasure of the different categories of data, and a general description of the technical and organizational security measures.

It will also help data processors keep a record of the categories of processing, transfers of personal data to a third country or an international organization, and a general description of the technical and organizational security measures.

Much of the information about personal data required for Article 30 compliance is also useful to meet obligations under Article 13 and Article 14 on information to be provided, for example, via privacy notices or consent forms.

Under Chapter 3 of the GDPR, data subjects have a number of rights. Understanding things such as the location, format, use of, and lawful basis of processing for different categories of personal data will enable will support responses to rights and requests.

Under Article 25 of the GDPR there are requirements for Data Protection by design and by default. Additionally, under Article 35 there are requirements relating to Data Protection impact assessments. The inventory can provide insight into which processes and systems need to be assessed based upon, for example, the nature, scope, context, and purposes of processing as well as the risks of varying likelihood and severity for rights and freedoms of natural persons posed by the processing.

As aforementioned, it is important to identify who the personal data is shared with. The inventory can support this as well as specifically enable monitoring of the existence or status or suitable agreements. For example, under Article 28 of the GDPR, processing by a processor shall be governed by a contract or other legal act under Union or Member State law.

Article 32 of the GDPR covers security of processing, with requirements to implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk. Then, using the inventory you can assess the security measures in place for assets against their level of confidentiality. It also can help with identifying the data sets where, if anything unfortunate were to happen, there are considerations regarding Article 33 Notification of a personal data breach to the supervisory authority and Article 34 Communication of a personal data breach to the data subject.

- Ownership: The ability to know: Who owns what? This includes understanding ownership both in terms of corporate accountability and ownership of the actual information itself. You could also record who administers an asset on a day-to-day basis if this is different.

- Business Continuity: An organization will have vital/business critical records that are necessary for it to continue to operate in the event of a disaster. They include those records that are required to recreate the organization's legal and financial status, to preserve its rights, and to ensure that it can continue to fulfill its obligations to its stakeholders. Assets can be classified within the IAR to an approved criticality classification scheme, with current protective measures recorded, in order to assess whether they are stored and protected in a suitable manner and identify if there are any risks relating to business critical (“vital record”) information. You can also identify the Recovery Point Objective (RPO) and Recovery Time Objective (RTO) for assets to support a disaster recovery or data protection plan.

- Originality: You can identify whether an asset is original or a copy, ascertaining its relative importance and supporting decisions on removing duplication and the optimization of business processes.

- Heritage: You can identify records of historical importance that can be transferred at some stage to the custody of a corporate or third-party archive.

- Formats: The ability to understand the formats used for information, supporting decisions on digital preservation or migration.

- Space Planning: In order to support office moves and changes, data can be gathered for physical assets relating to their volume, footprint, rate of accumulation, use, filing methods, and so on.

- Subject Matter: If assets are tagged to a business classification scheme of functions and activities, as well as potentially to a keyword list, the organization can understand the “spread” of record types (e.g. who holds personnel, financial, contractual records) and/or “discover” resources for knowledge management or e-discovery purposes.

- Archive Management: The ability to understand what physical records (paper, backup tapes, etc.) are archived, where and when; this might, for example, identify risks in specific locations or issues with the regularity of archiving processes. The organization can also understand its utilization of third-party archive storage vendors—potentially supporting decisions on contract management/consolidation—and maintain their own future-proof inventory of archive holdings. Archive transactions can be recorded if there is no system to otherwise do so.

- Location: The “location” of an asset can of course be virtual or physical. This (together with other questions relating to, for example, security measures) is important to ensure that information assets are suitably protected. It also helps in the planning of IT systems and physical filing/archiving services. The benefits for archive management are explored above and for maintaining a system catalogue below. Other examples might be to identify records to gather when doing an office sweep following vacation of a floor or building, or what assets are held in the cloud, or asset types within a given jurisdiction. It would also support the “discovery” of resources for knowledge management or e-discovery purposes.

- Retention: An IAR can be used both to link assets with approved records retention policies and understand the policies and methods currently applied within the organization, therefore identifying queries, risks, and issues. The IAR can also be used to maintain the actual policies (across jurisdictions if applicable) and their citations; if a law changes or is enacted, relevant assets can be identified for any process changes to be made.

- Disposal: An IAR can be used both to link assets with approved destruction or transfer policies and understand the processes and methods currently applied within the organization, therefore identifying queries, risks, and issues, particularly for confidential information. Disposal transactions can be recorded if there is no system to otherwise do so.

- Source: The source of assets can be identified to understand where information is derived from and better manage the information supply chain. Under article 14 of the GDPR, part of the information the controller shall provide to the data subject to ensure fair and transparent processing includes from which source the personal data originate, and if applicable, whether it came from publicly accessible sources.

- Rights: The rights held in and over assets can be identified, such as copyright and intellectual property, in order to protect IPR and to avoid infringement of the rights of others.

- Applications Catalogue: The application systems in use (e.g. content management, front and back office) can be identified and be linked in locations, people, activities, and, of course, assets. Licensing and upgrade criteria could also be managed. It would also be possible, for example, to identify system duplication or the use of homegrown databases.

- Condition: Both physical and digital assets can degrade: this can be identified for assets with conservation/preservation actions taken accordingly.

- Age: The age of assets can be established, with decisions made on their further retention/disposal, the need for archiving (historic or business), and potentially whether they need to be superseded with newer resources.

- Organization and Referencing: An understanding can be gained of whether structured systems and approaches are in place to describe, reference, and organize physical and digital assets, identifying if there are likely to be any issues with the finding information.

- Utilization: An understanding can be gained of whether assets are proposed, active, inactive, or discontinued/superseded, therefore enabling decisions on their format, storage, disposal, and so on.

- Sharing: An IAR can be used to identify how information is shared within and without the organization, helping to ensure that it is available as required, and that suitable security measures and, where applicable, information sharing agreements are in place. This supports compliance with Article 30 of the GDPR as part of the records of processing activities.

- Provenance: Fundamentally an IAR can provide an accountable audit trail of asset existence and activity, including any changes in ownership and custody of the resource since its creation that are significant for its authenticity, integrity, and interpretation.

- Publications: Information produced for wider publication to an internal or external resource can be identified, including, for example, the audience for whom the resource is intended or useful, the channels used for distribution and the language(s) of the content, thus facilitating editorial, production, and dissemination planning and management.

- Quality: Observations can be recorded on the quality of assets (e.g. accuracy, completeness, reliability, relevance, consistency across data sources, accessibility), with risks and issues identified and managed.

To help carry out Mr. Leming's approach to implementing and IAR, Mr. Kessler provided this succinct sample IAR survey, as shown in the following section.

Sample Information Asset Survey Questions28

- Information Asset Description

- 1.1 Name: A descriptive and meaningful label for the asset

- 1.2 Description: What is the information asset and what it is used for

- Ownership: This section covers the “stewardship” of the information asset, including the key roles and responsibilities of the owner and manager, together with any other stakeholders likely to be affected by the quality and availability of the asset.

- 2.1 Owner has overall accountability for access, use, and management of the asset

- 2.2 Manager: Hands-on manager responsible for day-to-day operations and administration. Expected to be familiar with the details of the asset content, structure and usage, and so likely to be quick to detect evidence of breach, tampering/corruption, and so on

- 2.3 Creator: Source of the information; a person, application system, or external source

- 2.4 Stakeholders/customers: Other stakeholders affected by the use, management, integrity, or availability of the asset

- Dates

- 3.1 Creation date: Date on which the asset was created (if involving a fixed lifecycle)

- 3.2 Last review date: Date on which the asset was last reviewed for completeness and accuracy

- 3.3 Date closed: Date on which the asset was closed/completed/removed from production use

- Confidentiality

- 4.1 Confidentiality: Indicates the confidentiality classification of the information based on the Confidentiality of Information policy, which is distinct from the Risk/Impact Criticality rating in section 7 below.)

- 4.2 Data Privacy and Protection: Indicates whether the asset contains or relates to Personally Identifiable Information (PII) and potential relevance to Data Protection or Data Privacy regulations and legal risk—especially the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- Retention

- 5.1 Retention period: Retention category (if useful—but avoid duplication and inconsistency)

- 5.2 System of Record: Name of the record system used to store the asset (or a subset of related business records)

- Access and Use

- 6.1 Applications and Interfaces: List of applications and interfaces authorized to access the information asset, together with the corresponding access rights

- 6.2 User groups: List of user groups authorized to access the asset, together with the corresponding access rights

- 6.3 Metadata: List of any metadata needed to access or describe the context of the asset

- Risk/Impact of problems/issues

- 7.1 Confidentiality: Impact if the asset is accessed or disclosed without authorization

- 7.2 Integrity: Impact if the information is corrupted, tampered with, or otherwise suffers a loss of integrity

- 7.3 Availability: Impact if the information is lost or unavailable?