CHAPTER 11

Information Governance and Privacy and Security Functions*

Privacy and security go hand in hand. Privacy cannot be protected without implementing proper security controls and technologies. Organizations must not only make reasonable efforts to protect privacy of data, but they must go much further as privacy breaches are damaging to customers and reputation. Potentially, they could put companies out of business.

Privacy and data protection awareness skyrocketed in 2018 with the implementation of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which gave new privacy rights to individuals in the EU and EU citizens everywhere, while creating significant new regulatory burdens on companies that handle personal data (PD), personally identifiable information (PII), and protected health information (PHI). Major corporations, after decades of automation, suddenly were being held to account for all instances and uses of personal consumer data. To do so, data maps and information flow diagrams had to be created to inventory all instances of stored personal data and learn how it flows through the organization.

This inventorying step is often one of the first in launching information governance (IG) programs, so the trend provided a significant increase in support for formal IG programs.

Information Privacy

By Andrew Ysasi

In a 2018 survey, Americans stated that they were more concerned with privacy than with healthcare or economic growth.1 Privacy came of age in 2018, when the EU GDPR went into effect. Its impact was felt across the globe, as citizens became more aware of privacy concerns.

Information privacy refers to individuals or corporations controlling what others know about them. Unlike information security, privacy is not objective, but subjective. What one believes needs to be private can vary. (Some think that privacy is a moral or legal right, while others have argued that privacy isn't about controlling information about oneself.)2 Privacy has been a widespread debate for the past century, and as the Internet has become engrained in societies and cultures, it will continue to be a concern for individuals and organizations.3 In the United States, personally identifiable information (PII) is used to determine privacy attributes, for example, last name, home address, place of birth, and so forth. Often, PII is referred to as information that is not publicly available or in public works.4

In the digital age, individuals who are concerned about their privacy are often at the mercy of the corporations and developers of software to control how an individual's information is used. Individuals often use apps to work, manage finances, socialize, and play games on smartphones or tablets. The apps on portable devices often require permission from the user to use the information to operate at their full potential. As a result, individuals permit the organizations that manage the apps to store passwords, credit card information, bank accounts, digital cookies, fingerprints, and a myriad of personal information. If apps or software have privacy controls, an individual may choose to restrict what information is stored, how it is used, and who their information can be shared with. In extreme cases, individuals may opt to share personal information on social media sites with little regard for their privacy. Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, Foursquare, and LinkedIn are some examples of social media where individuals may reveal a great deal of personal information.5

Organizations should have an interest in privacy. Whether consumers or employees demand privacy or privacy is regulated in the countries they operate is something an organization should understand and have plans to address. Many organizations have a responsibility to their shareholders to be profitable or, if not an entity to gain profit, ensure that they are meeting their mission within the guidelines of their corporate structure. Privacy concerns can have a direct impact on an organization. Organizations that are more driven by profits may have fewer privacy concerns or controls than organizations that provide significant privacy protection.6

Further, organizations may operate in jurisdictions or industries where there are laws or rules around privacy. For example, organizations should determine if they operate in an “opt-in” or “opt-out” jurisdiction, or if they are required to protect information because they operate in the healthcare or financial industries. Opt-in climates typically favor the privacy of the individual whereas opt-out favor an organization. Hospitals and insurance companies usually have laws and rules they need to follow to protect PII (personally identifiable information) or PHI (protected health information). Laws and regulations define what constitutes as PII and provide further guidance on how the information should be handled.

Criminals often target organizations to gain access to private information to sell or disrupt the organization. A database of privacy data breaches can be found at privacyrights.org. Privacyrights.org reports over 11.5 billion records have been breached from over 9000 breaches since 2005.7 As data breaches become more prevalent, governments and privacy professionals have advocated for strict laws to protect individuals. Scholars believe that net neutrality, the Internet of Things (IoT), the human genome (medical), and cryptocurrencies will impact privacy for individual and organizations throughout the next decade.8

Generally Accepted Privacy Principles

The Generally Accepted Privacy Principles (GAPP) can be used to guide privacy programs. Please see Chapter 3 for more detail.

Privacy Policies

Privacy policies are ways for organizations to explain what they do with PII. Privacy policies may be found on websites or may be used internally only at an organization. Researchers predict that organizations will have tools available for individuals to choose how their information is used via privacy policies.9 The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) has provided a template for organizations,10 and it includes the following:

- Why the policy exists—to comply with a law or protection from a data breach.

- Data protection laws—specific examples of laws the organization is subject to follow.

- Policy scope—who the policy applies to, employees, contractors, vendors, and individual.

- Data protection risks—identifying to users what could happen if private information is provided.

- Responsibilities—an explanation of what the organization is responsible to protect, who or whom is ultimately is responsible (e.g. board of directors, data protection officer, privacy officer, IT manager, marketing manager) and what will be done to protect information.

- Guidelines for staff—not sharing information, using a strong password, not sharing credentials, not disclosing information unnecessarily.

- Data storage—how information is stored and where it may be stored.

- Data use—why information is needed for businesses and what is done to the information.

- Data accuracy—that data collected is accurate, updated when wrong, and a way for individuals to report inaccurate information.

- Subject access requests—how individuals can determine what is collected about them and how they can retrieve or edit the information.

- Disclosure—the possibility of disclosing information to authorities or for legal reasons.

- Providing information—clarification on how an individual's information is being processed and what their rights are.11

The IAPP has a privacy policy version that includes the European Union's GDPR provisions for organizations that must comply with the GDPR privacy requirements that can be found at the same site as the template outlined above.

Privacy Notices

Privacy notices are typically exclusive to external facing stakeholders or to the public, where privacy policy could be both.12 The Better Business Bureau in the United States advises that a privacy notice should include five elements:

- Notice (what personal information is being collected on the site or by the organization)

- Choice (what options the customer has about how/whether personal data is collected and used)

- Access (how a customer can see what data has been collected and change/correct it if necessary)

- Security (state how any data that is collected is stored/protected)

- Redress (what customer can do if the privacy policy is not met)

Fair Information Practices (FIPS)

HEW Report

“The first steps toward formally codifying Fair Information Practices began in July 1973, when an advisory committee of the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare proposed a set of information practices to address a lack of protection under the law at that time.”13

As a result of this group, the HEW report was created formerly known as the Records, Computers and the Rights of Citizens. The HEW report summarized fair information practices as:

- There must be no personal data recordkeeping systems whose very existence is secret.

- There must be a way for an individual to find out what information about him is in a record and how it is used.

- There must be a way for an individual to prevent information about him obtained for one purpose from being used or made available for other purposes without his consent.

- There must be a way for an individual to correct or amend a record of identifiable information about him.

- Any organization creating, maintaining, using, or disseminating records of identifiable personal data must assure the reliability of the data for their intended use and must take reasonable precautions to prevent misuse of the data.14

OCED Privacy Principles

In 1980, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published guidelines on the protection of privacy and personal data and were recently updated in 2013.15 The eight fair information principles outlined by the OECD are as follows.

Collection Limitation Principle

There should be limits to the collection of personal data, and any such data should be obtained by lawful and fair means and, where appropriate, with the knowledge or consent of the data subject.

Data Quality Principle

Personal data should be relevant to the purposes for which they are to be used, and, to the extent necessary for those purposes, should be accurate, complete, and kept up to date.

Purpose Specification Principle

The purposes for which personal data are collected should be specified not later than at the time of data collection, and the subsequent use limited to the fulfillment of those purposes or such others as are not incompatible with those purposes and as are specified on each occasion of change of purpose.

Use Limitation Principle

Personal data should not be disclosed, made available, or otherwise used for purposes other than those specified in accordance with Paragraph 9 except:

- With the consent of the data subject; or

- By the authority of law.

Security Safeguards Principle

Personal data should be protected by reasonable security safeguards against such risks as loss or unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure of data.

Openness Principle

There should be a general policy of openness about developments, practices, and policies concerning personal data. Means should be readily available for establishing the existence and nature of personal data, and the main purposes of their use, as well as the identity and usual residence of the data controller.

Individual Participation Principle

An individual should have the right:

- To obtain from a data controller, or otherwise, confirmation of whether or not the data controller has data relating to him;

- To have communicated to him, data relating to him within a reasonable time;

at a charge, if any, that is not excessive;

in a reasonable manner; and

in a form that is readily intelligible to him;

- To be given reasons if a request made under subparagraphs (a) and (b) is denied, and to be able to challenge such denial; and

- To challenge data relating to him and, if the challenge is successful to have the data erased, rectified, completed, or amended.

Accountability Principle

A data controller should be accountable for complying with measures which give effect to the principles stated above.

Madrid Resolution 2009

In 2009, the Madrid Resolution brought 50 countries together to provide further guidance on information privacy. The resolution was designed and signed by executives from 10 international organizations, and one of the most important recommendations is governments “promoting better compliance with the applicable laws regarding data protection matters.”16

While the Madrid Resolution was a big step in achieving global privacy awareness and guidance, it was merely viewed as a starting point for addressing the dynamic landscape of personal privacy across the globe. In 2010, the United States Department of Health Services Privacy Office stated an opinion on the Madrid Resolution, specifically criticizing the fact that governments and regulatory authorities were not included, and recommending that all stakeholders be involved in the development of a global privacy framework.17 It is also worth noting the Director of the Spain Data Protection Agency (AEPD), Artemi Rallo: “These standards are a proposal of international minimums, which include a set of principles and rights that will allow the achievement of a greater degree of international consensus and that will serve as reference for those countries that do not have a legal and institutional structure for data protection.”18 It appeared in 2010 that a global privacy framework was on the horizon.

EU General Data Protection Regulation

The European Union's Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provided the most significant privacy framework, policy, and regulatory overhaul history.

“In 2016, the EU adopted the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), one of its greatest achievements in recent years. It replaces the 1995 Data Protection Directive which was adopted at a time when the Internet was in its infancy.”19

Compliance for GDPR and enforceability requirements went into effect on May 28, 2018, and required organizations to seek consent from individuals before collecting their personal information.20 Further, GDPR requires organizations to assign a Data Controller and provides specific principles related to the processing of personal data found in article 5:

Personal data shall be:

- Processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject (“lawfulness, fairness and transparency”);

- Collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes; further processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific, or historical research purposes or statistical purposes shall, in accordance with Article 89(1), not be considered to be incompatible with the initial purposes (“purpose limitation”);

- Adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed (“data minimization”);

- Accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date; every reasonable step must be taken to ensure that personal data that are inaccurate, having regard to the purposes for which they are processed, are erased or rectified without delay (“accuracy”);

- Kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the personal data are processed; personal data may be stored for longer periods insofar as the personal data will be processed solely for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes in accordance with Article 89(1) subject to implementation of the appropriate technical and organisational measures required by this Regulation in order to safeguard the rights and freedoms of the data subject (“storage limitation”);

- Processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of the personal data, including protection against unauthorized or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organizational measures (“integrity and confidentiality”).21

Failure to comply with GDPR requirements comes with hefty penalties. Fines are not assessed without an investigation and guidance. GDPR outlines the 10 criteria to determine the amount an organization can be fined:

- Nature of infringement: The number of people affected, damage they suffered, duration of infringement, and purpose of processing.

- Intention: Whether the infringement is intentional or negligent.

- Mitigation: Actions taken to mitigate damage to data subjects.

- Preventative measures: How much technical and organizational preparation the firm had previously implemented to prevent noncompliance.

- History: Past relevant infringements, which may be interpreted to include infringements under the Data Protection Directive and not just the GDPR, and past administrative corrective actions under the GDPR, from warnings to bans on processing and fines.

- Cooperation: How cooperative the firm has been with the supervisory authority to remedy the infringement.

- Data type:: What types of data the infringement impacts.

- Notification: Whether the infringement was proactively reported to the supervisory authority by the firm itself or a third party.

- Certification: Whether the firm had qualified under approved certifications or adhered to approved codes of conduct.

- Other: Other aggravating or mitigating factors may include the financial impact on the firm from the infringement.22

Lower-level fines can be up to €10 million, or 2% of the worldwide annual revenue of the prior fiscal year, whichever is higher. Higher-level fines can be up to €20 million, or 4% of the worldwide annual revenue of the prior fiscal year, whichever is higher.23 The EU is quite evident through GDPR that consumer privacy is of the utmost importance, and organizations that choose to mishandle the data of EU citizens will suffer substantial financial losses. On the day that organizations were required to be compliant, Facebook and Google were hit with over $8 billion in lawsuits.24 Facebook and other large companies seem to be making strides to comply, but other organizations are trying to block EU citizens from their sites to mitigate risk.25 GDPR provides comprehensive oversight and guidance on how to protect consumer information and what happens if an organization does not comply. However, it is yet to be determined if GDPR will provide adequate privacy protection of consumer data without hindering EU citizens from experience foreign sites or companies wishing to expand their market in the EU.

GDPR: A Look at Its First Year

By Mark Driskill

The EU implemented sweeping new data privacy and protection laws meant to protect the personal data (PD) of those in the EU—importantly—be they citizens, temporary residents or visitors, from unauthorized use, and, extraterritorially, wherever in the world their personal data is stored or used.

The issues stem from the EU's broad definition of PD and the long history in Europe of privacy being viewed as a fundamental human right, against too much history of dictatorships and fascist control. The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took effect, provoking a new era of tech-company corporate accountability.

The GDPR didn't just standardize data privacy and protection across all (current) 28 member states of Europe, but refined both how to seek permission to use personal data and refresh the personal rights of each person in the EU to view and take control of their own personal data.

As 2018 came to a close, it was revealed that some major tech companies use personal data in ways that violate personal privacy in many ways.

Large data handlers like Facebook, Google, and Amazon have come under close examination by EU regulators, forcing CEOs in the “personal surveillance data business” to defend, and even rethink, their business models (e.g. Google then cited privacy regulation as a major threat to their business model in corporate documents). These have included both Privacy Regulators around GDPR (e.g. UK ICO, Ireland DPC, etc.) and EU competition regulators. Under the new GDPR these companies, without exception, must follow EU privacy law. The issues rest primarily with the advertising data insights these companies have created using proprietary algorithms. The invasiveness is secretive and at times unsettling, as these companies seem to know when someone will buy a pair of socks!

At first glance, it might seem as if the first year of GDPR compliance was largely uneventful, at least in terms of other leading global news stories. It's really a journey, as the EU regulators and analysts have shared. With almost 95,000 privacy complaints filed, they have only just started to process those investigations, findings, and enforcements. So many of the “privacy fines” we've seen since GDPR went live were really cases that occurred pre-GDPR and were thus much smaller in scope and penalties under the prior EU privacy regulation. What has been happening quietly, almost behind the scenes, is a tacit acceptance that data privacy from the person-centered perspective must begin with forcing larger companies such as Facebook, Google, and Amazon to comply. This hangs over companies in the consumer tech sector like thick fog. American businesses and culture do not like anyone telling them how to run things. Apparently, this is also true for GDPR compliance, adding to a persistent lack of full compliance.

A December 2018 Forrester survey commissioned by Microsoft found that more than half of businesses failed to meet GDPR compliance checkpoints.26 Other highlights included:

- 57% instituted “privacy by design.”

- 59% “collected evidence of having addressed GDPR compliance risks.”

- 57% “trained business personnel on GDPR requirements.”

- 62% “vetted third-party vendors.”

This last item is perhaps the most troubling: 38% have yet to vet their third-party software vendors. This means that a significant portion of the global economy is not meeting GDPR compliance. The Forrester survey's primary findings were that only 11% of global companies are prepared to undergo the type of digital transformation needed to fully comply with GDPR-based privacy needs of citizens. In its entirety, GDPR has yet to make a significant impact, at least one beyond large tech company compliance.

A key implied issue that ultimately influences GDPR compliance checkpoints is the balance between intrusion into a company's business practices and its ability for profitmaking. Industry leaders note that in order to truly protect personal data, you must know exactly where and whose it is. This necessarily requires intrusion.

Enforcement and Precedent Setting

With the new GDPR mandate in place, EU member countries have a valuable tool for ensuring compliance even as these companies undertake actions to protect their business models. Ireland, for example, has “opened 10 statutory inquiries into Facebook and other Facebook-owned platforms in the first seven months” since GDPR was adopted in May 2018.27

The Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) commissioner Helen Dixon notes that the inquiries match the public's interest in “understanding and controlling” their own personal data. The Irish DPC fully intends that these be precedent-setting. Given the widespread global use of Facebook and its plethora of connected apps, such inquiries from other EU member countries cannot be far behind.

In perhaps the most egregious case yet, a whistleblower forced Facebook to reveal that “as many as 600 million users’ passwords were stored in plain text and accessible to 20,000 employees, of which 2000 made more than 9 million searches that accessed the passwords going back to 2012.”28 Added to this blatant breach of basic cybersecurity practices is the fact that Facebook knew about the issue back in January and spent several months trying to keep it from the public.29 They would surely have been embarrassing questions to answer during the recent US Congressional hearings.

As Forbes points out, cybersecurity at Facebook just might be obsolete. In the wake of the sensational stories regarding recent Russian interference into American elections, “Facebook did not conduct a top-down security audit of its authentication systems.” This is a profound, if not provocative, revelation, particularly given Mark Zuckerberg's promise to reform Facebook's business practices.

That promise, made to Congress just prior to GDPR's May 2018 rollout, seems now to be empty. While Zuckerberg testified, his company continued its intrusive practices, even as he tried to simplify for legislators Facebook's business practices.

In the business world, laws and regulations are street signs to setting precedent. During this initial phase of GDPR compliance, it is crucial that leading EU countries, such as Germany, take positions of authority. Germany's Federal Cartel Office, the federal agency that regulates Germany's competition laws, set a new precedent in a February 2019 court ruling. In an anti-competition class-action case, the German court severely limited Facebook's ability to collect user data inside Germany. This essentially walls off Germany's Facebook users from the rest of Facebook's user base. The precedent set by German regulators was substantial. Facebook (at least in Germany) can longer use tactics such as using user data to make fictitious profiles. Moreover, it can no longer use Facebook Pixel, a single character imbedded in a page that transmits data back to the company's servers. With the German precedent, Facebook can no longer claim that what it does with user data on its platform is proprietary.

In some ways, the first year of “GDPR-live” was marked by both confusion and denial that such regulation was really needed. Today, the establishment of a nation-specific precedent is the exception, not the rule. However, enough cannot be said about the fact that Germany is one of the main economic powers of the globe. Without German leadership, GDPR might die an unceremonious death. The same must happen in other countries involved in setting global economic policy.

In short, GDPR-style privacy must come to the United States. Thankfully, California is leading the way with its California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which went live in January 2020.

Privacy Programs

Privacy programs are often required to manage the national and international requirements to protect consumer information. The IAPP has a rigorous certification called the Certified Information Privacy Manager (CIPM), and the outline30 for the exam provides a framework to build a privacy program.

- Vision—The purpose of the privacy program and what the program will achieve.

- Team—Key stakeholders who have direct responsibility for privacy matters that may include a Chief Privacy Officer (CPO), Data Protection Officer (DPO), Data Controller (DC), executive sponsorship, inside or outside legal counsel, technology leadership, compliance leadership, and records and information leadership.

- Policies—Privacy policies for websites, social media, e-mail, mobile apps, internal practices, and privacy policies addressing applicable international, national, and local laws should be reviewed and examined.

- Activities—Examples of activities are training, awareness, updating agreements with key stakeholders, addressing cross-border concerns, reviewing insurance and assurance options, evaluating privacy compliance software tools, and conducting privacy impact assessments along with specific risk assessments that relate to privacy concerns or regulations.

- Metrics—Collection, responses time to inquiries, retention, PIA metrics, maturity levels, and resource utilization are some examples of how organizations can measure privacy.

Privacy in the United States

FCRA

Privacy in the United States has a fairly recent history. In 1970, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) was placed into law to protect consumers. With the FCRA, consumers were able to correct errors on their credit report.31 FCRA was amended in 1996 and again in 2003 by the Fair and Accurate Credit Transaction Act that addresses issues related to identity theft. Under FCRA there are obligations users of credit reports must follow, which include:

- Users must have a permissible purpose—as in the uses of credit reports are limited.

- Users must provide certifications—they have a right to request the report.

- Users must notify consumers when adverse actions are taken—users must be notified if their credit was a result of something not occurring.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) provided updates to the FCRA on their website located at www.ftc.gov.32 Further, the FTC is the enforcement arm of FCRA and FACTA.

HIPAA

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 was created to improve the delivery of healthcare services and to provide standards on how patient records are handled in data exchanges. HIPAA oversight is provided by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under the Office for Civil Rights (OCR).33 Entities covered under HIPAA are:

- Health care providers

- Health plans

- Health care clearinghouses

The entities were broken up into two Covered Entities (CE) and Business Associates (BA) and personal information they managed is referred to as Protected Health Information (PHI).

Protected health information is any individually identifiable health information transmitted or maintained in any form or medium, which is held by a covered entity or its business associate, identifies an individual or offers a reasonable basis for identification, is created or received by a covered entity or an employer, and relates to a past, present or future physical or mental condition, provision of health care or payment for health care to that individual.34

In 2000, HIPAA was amended to include the “Privacy Rule” that required:

- Privacy Notices

- Authorization of Uses and Disclosures

- Access and Accountings of Disclosures

- “Minimum Necessary” Use or Disclosure

- De-identification

- Safeguards

- Business Associates accountability

- Exceptions35

In 2003, HIPAA was amended further with the Security Rule, which focused on the protection of electronic medical records. It required covered entities to:

- Ensure confidentiality of electronic medical records

- Protect against any threats or hazards to the security or integrity of records

- Protect against any reasonably anticipated users or disclosures that are not permitted

- Ensure compliance with the Security Rule by the staff

- Identify an individual responsible for implementation and oversight of the Security Rule and compliance program

- Conduct an initial and ongoing risk assessments

- Implement a security awareness program

- Incorporate Security Rule requirements into Business Associate Contracts required by the Privacy Rule

In 2009, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act was enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 to promote the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology.36 Further, HITECH separated out four categories of how fines would be distributed, and another noteworthy change was the correction of a violation within 30 days.37 Below is the penalty structure for HIPAA violations:

- Category 1: A violation that the covered entity was unaware of and could not have realistically avoided, had a reasonable amount of care had been taken to abide by HIPAA Rules.

- Category 2: A violation that the covered entity should have been aware of but could not have avoided even with a reasonable amount of care (but falling short of willful neglect of HIPAA Rules).

- Category 3: A violation suffered as a direct result of “willful neglect” of HIPAA Rules, in cases where an attempt has been made to correct the violation.

- Category 4: A violation of HIPAA Rules constituting willful neglect, where no attempt has been made to correct the violation.38

Other US Regulations

The United States has scores of other regulations that have shaped the US privacy landscape:

The Graham-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) issued in 1999 prohibited the sale of detailed customer information to, for example, telemarketing firms. GLBA is enforced by the FTC and allows consumers to “opt out” of having their information shared with affiliates. Like HIPAA, GLBA has safeguards and requires administrative, technical, and physical security of consumer information as well as privacy notice requirements.

The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 2000 (COPPA) was the result of the FTC's 1998 Privacy Online: A Report to Congress.39 Privacy related to children in the United States was the primary focus of COPPA, and required website companies and other operaters to adhere to a set of requirements, including privacy notices, or be subject to fines.

Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act of 2003 (CAN-SPAM) applies to anyone who advertises products and services by e-mail generated in the United States.40 CAN-SPAM's aim is to reduce deceptive advertising by e-mail, include warnings for sexually explicit content, and the ability to opt-out from future e-mails. CAN-SPAM is governed by the FTC.

Certain states in the United States have taken action to protect the privacy of citizens.

Massachusetts rolled out 940 CMR 27.00: Safeguard of personal information in 201041 and the California Consumer Privacy Act in 2018, which will be enforceable in 2020,42 focus on privacy and security of citizen information as a result of ongoing data breaches. What information is collected, specifically by social media entities Facebook and Google, why it is collected, and obtaining personal information in usable formats are some highlights of the California law. The law also requires children under 16 to opt in to allowing companies to collect their information.43 Further, it is thought that future privacy laws from other states may modify their privacy laws to mirror California.

California Consumer Privacy Act

California's new privacy law went into effect on January 1, 2020. This act is designed to give California residents a better way to control and protect their personal information. California consumers will have the right to order companies to delete their personal data—similar to what Europe's all-encompassing GDPR regulation calls for (but not as strict). Many US states have begun debating new privacy laws using the CCPA and GDPR as models to protect the personal rights of individuals and consumers.44

Privacy regulations are rapidly spreading worldwide in countries such as India, Brazil, and Australia. Even the US Congress has been working on a bill that could soon become federal law.

California consumers will have the legal right to force companies to not only delete their personal information but also disclose what personally identifiable information (PII) has been collected about them, demand the reasons for collecting it, and order the companies to refrain from selling any of it. The personal information protected in these regulations contains a lot more than just financial or banking data; PII includes all “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is associated with, or could be reasonably linked, directly or indirectly, to a consumer or household.” This consists of many different types of information, including IP addresses, biometric data, personal characteristics, browsing history, geolocation data, and much more.

On June 28, 2018, the California Congress passed Assembly Bill 375, the CCPA. The act will apply to any “for-profit” organization that grosses at least $25 million annually and interacts with 50,000 or more Californians, or derives at least half of its annual revenue from selling personal information. Most importantly, the CCPA applies to businesses “regardless of location” that meet the above criteria. You must comply if you process personal information of Californians whether your corporation is located in California or not.

What was interesting is how the CCPA was rushed into law and signed by Governor Jerry Brown in June of 2018, just days before a deadline to withdraw a state ballot measure on a privacy proposition coming up in the November election. Tech companies like Google and Facebook were ready to fight against this voter initiative because it would have been more strict—holding them more accountable with more far-reaching rules and heavier fines. These same tech giants are currently lobbying congress in Washington, DC, to create new federal privacy laws. Not surprisingly, big tech companies are only looking out for themselves as they try to preserve their “surveillance” business model by watering down impending privacy legislation.

It is important to note that the CCPA has already been amended and politicians promise to make more changes before the CCPA goes into full effect in January 2020.

Privacy in Asia

The Asia-Pacific region is no stranger to privacy concerns. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) endorsed the 1998 Blueprint for Action on Electronic Commerce that discussed the creation of a fair and open digital economy that promoted confidence and trust with consumers. In 2005, APEC published their privacy principles that included:

- Preventing harm

- Notice

- Collection limitations

- Uses of personal information choice

- Integrity of personal information

- Security safeguards

- Access and correction

- Accountability45

In 2015, APEC added the principle of Choice, which emphasized that individuals should have a choice in how their information is used.46 The APEC privacy framework also provides implementation guidelines to guide organizations of all types on how to implement the privacy framework.

Infonomics and Privacy

Doug Laney explored a concept known as infonomics in his seminal 2018 book that discussed how organizations could monetize, manage, and measure information as an asset.47 While the use of internal or consumer data raises privacy concerns, Laney suggests viewing data as an asset and working within the privacy and legal parameters to maximize the value of information. Sometimes this may involve spinning off a new legal entity to provide some distance between the parent company and a data monetization venture, for legal and branding purposes. Laney's book discusses how information is used to generate new revenue for marketing purposes, providing access to third parties and streamlining operations. While these concepts may go against general privacy principles, it is possible to navigate privacy concerns with Laney's ideas. He provides “Seven Steps to Monetizing Your Information Assets,” and goes on to explain how to report your information assets on your balance sheets, and provides formulas. While doing so, it is essential to understand the impact of privacy risks associated with monetizing information.

Privacy Laws

The protection of personally identifiable information (PII) is a core focus of IG efforts. PII is any information that can identify an individual, such as name, Social Security number, medical record number, credit card number, and so on. Various privacy laws have been enacted in an effort to protect privacy. You must consult your legal counsel to determine which laws and regulations apply to your organization and its data and documents.

The CCPA is waking up other US states to the need for more robust privacy legislation, while at the same time there is a move underfoot for the first national privacy legislation. If this goes forward, then there will be legal battles regarding preemption of the federal law in states having stricter privacy laws, using a “states’ rights” argument, and the federal government will argue that they have preemptive legal authority.

The Federal Wiretap Act “prohibits the unauthorized interception and disclosure of wire, oral, or electronic communications.” The Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986 amended the Federal Wiretap Act significantly and included specific on e-mail privacy.48 The Stored Communications and Transactional Records Act (SCTRA) was created as a part of ECPA and is “sometimes useful for protecting the privacy of e-mail and other Internet communications when discovery is sought.” The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act makes it a crime to intentionally breach a “protected computer” (one used by a financial institution or for interstate commerce).

Also relevant for public entities is the Freedom of Information Act, which allows US citizens to request government documents that have not previously been released, although sometimes sensitive information is redacted (blacked out) and specifies the steps for disclosure as well as the exemptions. In the United Kingdom, the Freedom of Information Act 2000 provides for similar disclosure requirements and mandatory steps.

In the United Kingdom, privacy laws and regulations include the following:

- Data Protection Act 1998

- Freedom of Information Act 2000

- Public Records Act 1958

- Common law duty of confidentiality

- Confidentiality National Health Service (NHS) Code of Practice

- NHS Care Record Guarantee for England

- Social Care Record Guarantee for England

- Information Security NHS Code of Practice

- Records Management NHS Code of Practice

Also, the international information security standard ISO/IEC 27002: 2005 comes into play when implementing security.

Cybersecurity

Breaches are increasingly being carried out by malicious attacks, but a significant source of breaches is internal mistakes caused by poor information governance (IG) practices, software bugs, and carelessness. The average cost of a data breach in 2018 was nearly $4 million,49 and some spectacular breaches have occurred, such as the 87 million–plus Facebook accounts and 37 million Panera accounts that were hacked in 2018,50 but perhaps the most colossal was the breach of over 500 million customer records, including credit card and passport numbers, suffered by the Marriott Hotel chain that same year.51 Millions of breaches occur each year: There were an estimated 179 million privacy breaches in the United States in 2017 alone.52

Cyberattacks Proliferate

Online attacks and snooping continue at an increasing rate. Organizations must be vigilant about securing their internal, confidential documents and e-mail messages. In one assessment, security experts at Intel/McAfee “discovered an unprecedented series of cyberattacks on the networks of 72 organizations globally, including the United Nations, governments and corporations, over a five-year period.”53 Dmitri Alperovitch of McAfee described the incident as “the biggest transfer of wealth in terms of intellectual property in history.”54 The level of intrusion is ominous.

The targeted victims included governments, including the United States, Canada, India, and others; corporations, including high-tech companies and defense contractors; the International Olympic Committee; and the United Nations. “In the case of the United Nations, the hackers broke into the computer system of its secretariat in Geneva, hid there for nearly two years, and quietly combed through reams of secret data, according to McAfee.”55 Attacks can be occurring in organizations for years before they are uncovered—if they are discovered at all. This means that an organization may be covertly monitored by criminals or competitors for extended periods of time.

And they are not the only ones spying—look no further than the US National Security Agency (NSA) scandal of 2013. With Edward Snowden's revelations, it is clear that governments are accessing, monitoring, and storing massive amounts of private data.

Where this stolen information is going and how it will be used is yet to be determined. But it is clear that possessing this competitive intelligence could give a government or company a huge advantage economically, competitively, diplomatically, and militarily.

The information assets of companies and government agencies are at risk globally. Some are invaded and eroded daily, without detection. The victims are losing economic advantage and national secrets to unscrupulous rivals, so it is imperative that IG policies are formed, followed, enforced, tested, and audited. It is also imperative to use the best available technology to counter or avoid such attacks.56

Insider Threat: Malicious or Not

Ibas, a global supplier of data recovery and computer forensics, conducted a survey of 400 business professionals about their attitudes toward intellectual property (IP) theft:

- Nearly 70% of employees have engaged in IP theft, taking corporate property upon (voluntary or involuntary) termination.

- Almost one-third have taken valuable customer contact information, databases, or other client data.

- Most employees send e-documents to their personal e-mail accounts when pilfering the information.

- Almost 60% of surveyed employees believe such actions are acceptable.

- Those who steal IP often feel that they are entitled to partial ownership rights, especially if they had a hand in creating the files.57

These survey statistics are alarming, and by all accounts the trend continuing to worsen today. Clearly, organizations have serious cultural challenges to combat prevailing attitudes toward IP theft. A strong and continuous program of IG aimed at securing confidential and sensitive information assets can educate employees, raise their IP security awareness, and train them on techniques to help secure valuable IP. And the change needs to be driven from the top: from the CEO and boardroom. However, the magnitude of the problem in any organization cannot be accurately known or measured. Without the necessary IG monitoring and enforcement tools, executives cannot know the extent of the erosion of information assets and the real cost in cash and intangible terms over the long term.

Countering the Insider Threat

Frequently ignored, the insider has increasingly become the main threat—more than the external threats outside of the perimeter. Insider threat breaches can be more costly than outsider breaches. Most of the insider incidents go unnoticed or unreported.58

Companies have been spending a lot of time and effort protecting their perimeters from outside attacks. In recent years, most companies have realized that the insider threat is something that needs to be taken more seriously.

Malicious Insider

Malicious insiders and saboteurs comprise a very small minority of employees. A disgruntled employee or sometimes an outright spy can cause a lot of damage. Malicious insiders have many methods at their disposal to harm the organization by destroying equipment, gaining unsanctioned access to IP, or removing sensitive information by USB drive, e-mail, or other methods.

Nonmalicious Insider

Fifty-eight percent of Wall Street workers say they would take data from their company if they were terminated, and believe they could get away with it, according to a recent survey by security firm CyberArk.59 Frequently, they do this without malice. The majority of users indicated having sent out documents accidentally via e-mail. So, clearly it is easy to leak documents without meaning to do any harm, and that is the cause of most leaks.

Solutions

Trust and regulation are not enough. In the case of a nonmalicious user, companies should invest in security, risk education, and Security Awareness Training (SAT). A solid IG program can reduce IP leaks through education, training, monitoring, and enforcement. SAT raises user awareness and can be gamified to increase engagement and effectiveness. Newer SAT programs utilize animated cartoon-like videos to keep users interested and engaged.

In the case of the malicious user, companies need to take a hard look and see whether they have any effective IG enforcement and document life cycle security (DLS) technology such as information rights management (IRM) in place. Most often, the answer is no.60

Information Security Assessments and Awareness Training

By Baird Brueseke

Employees’ human errors are the weakest link in securing an organization's confidential information. However, there are some small, inexpensive steps (through employee training) that can reduce information risk.

Security Awareness Training (SAT) programs educate an organization's workforce about the risks to information and potential schemes employed by hackers. SAT provides them with the skills to act consistently in a way that protects the organization's information assets. Bad actors target an employee's natural human tendencies with phishing e-mails and spear-phishing campaigns. SAT training programs often include phishing simulation and other social-engineering tactics such as text message “smishing” and unattended USB drives. SAT products provide a comprehensive approach to employee training, which empowers them to recognize and avoid a broad range of threat vectors.

SAT is an easy effective and easy way to reduce risk. Corporate risk is reduced by changing the (human) behavior of employees. Leading products in this market use innovative methods such as short, animated videos and pop quizzes to teach employees about information security threats.

SAT is not a one-and-done activity. In order to be effective, SAT must be implemented as an ongoing process. Workplace safety programs implemented to meet OSHA requirements serve as a good metaphor. SAT is a continuous improvement process; new threats emerge every day. The leading products incorporate new content on a regular basis and provide employee engagement opportunities that go well beyond the traditional computer-based training activities.

SAT Is a Quick Win for IG Programs

One of the quick—and low cost—wins that an Information Governance (IG) program can bring to an organization is the implementation of an SAT program. IG programs are implemented to reduce risk and maximize information value. Security Awareness Training programs are an excellent way to reduce risk and they are easy to implement. Employees have many bad habits that can leave a company vulnerable to data breach scenarios.

In response to the ever-increasing cyber security threat faced by business, a new subsegment of the Information Security market has emerged and matured in the last five years. The Security Awareness Training market grew 54% from 2015 to 2017. Projected revenues for 2018 were $400 million and growth was strong.

Cybersecurity threats are constantly evolving. One of the important things to understand when evaluating Security Awareness Training programs is the vendor's cycle for new content development and deployment in the training platform. Some of the features to look for and evaluate when selecting a SAT product are:

- Interactive content in varied formats designed to keep learners engaged

- Training designed to teach resistance to multiple forms of social engineering

- Optimization for smartphone and tablet usage

- Gamification and other methods to engage employees and increase participation

- Prestructured campaigns for different types/levels of employees

- Role-based training with optional customization based on corporate environment

- Robust library of existing content and flexible micro-learning topics

- Internal marketing and communication tools for use by the HR department

- Short lessons, approximately 5–10 minutes in length

- Integrated quizzes and metrics to track employee participation and retention

- Integration with corporate LMS

- Integration with end-point security systems

It is important to understand that SAT products typically include not only training, but also simulated attacks. Therefore, the way in which the SAT product interacts with existing cybersecurity defenses is a serious consideration. For example, if the training program administrator sends out a simulated phishing attack e-mail, that e-mail needs to make it through the SPAM filter and into the employee's e-mail inbox before the employee can be tempted into potentially clicking on the bad link.

In smaller companies, it may be sufficient to whitelist to the domain from which the phishing e-mail is being sent. In larger organizations that have Security Information Event Monitoring (SIEM) and other automated cyber defense systems, the company's IT/Security Team would likely request integration of a notification process for the simulated attack campaign in order to avoid a rash of false alarms from the security monitoring systems.

Security Awareness Training can provide a quick win for IG programs. The training immediately reduces risk. At the same time, management can point to the employee participation metrics as proof that proactive efforts are being made to enhance the organizations’ security posture.

Cybersecurity Assessments

In today's cyber threat landscape, companies have a fiduciary duty to assess their cyber security posture. This is the root function of a Cybersecurity Assessment. Typically, third-party vendors are contracted to perform the Assessment. These firms have expertise in a variety of cybersecurity skills that they use to tailor the engagement to a scope appropriate for the organization being assessed.

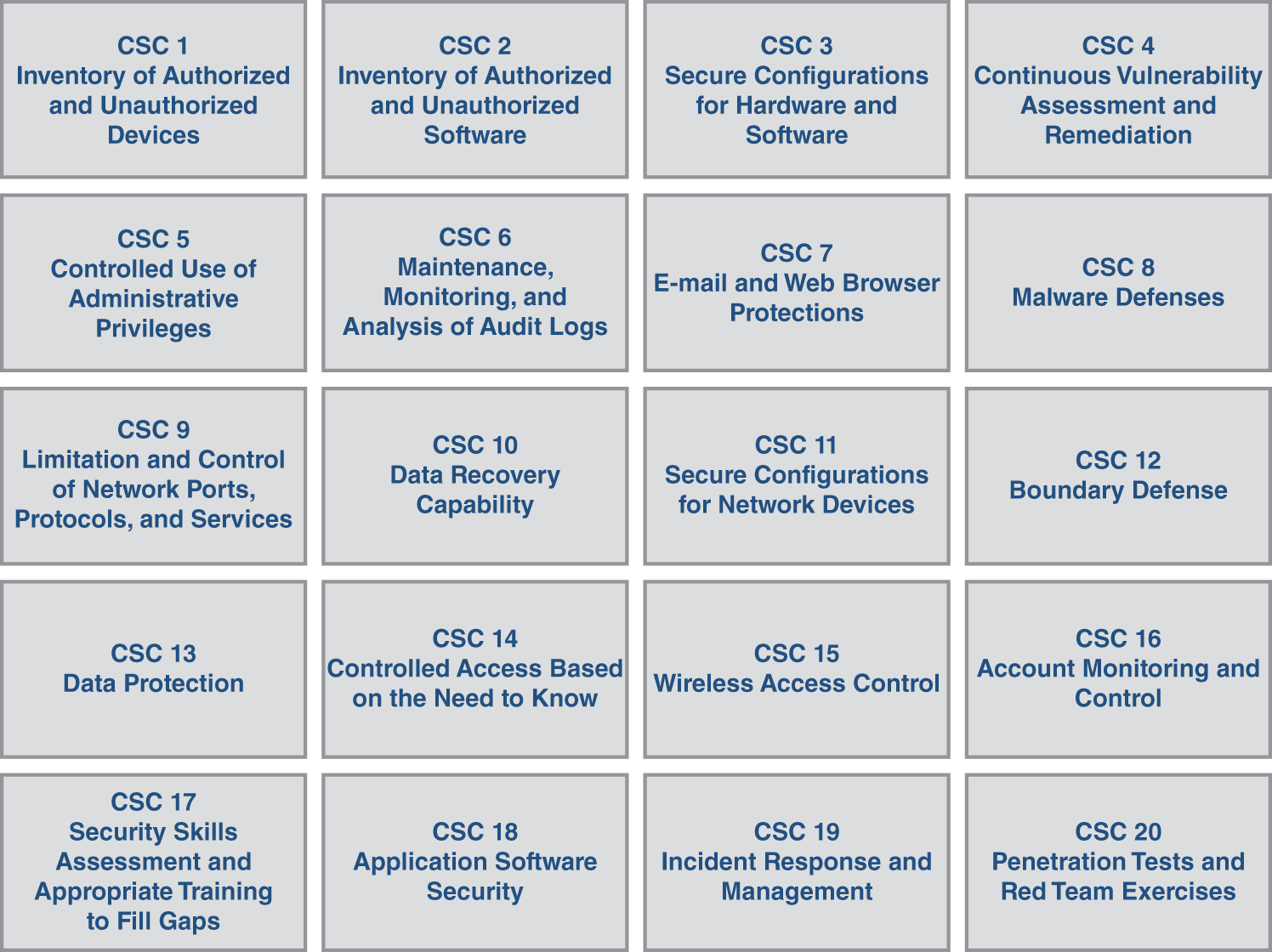

One of the first steps when starting a Cybersecurity Assessment project is to select a framework. This choice will become part of the project requirements and in large part define the scope of work to be performed by the third-party vendor. There are several frameworks to choose from including: ISO 27001, COBIT 2019, NIST Cybersecurity Framework, NIST 800-53, DOD 8570, DCID 6/3, HITRUST CSF, and the Cloud Security Alliance's Cloud Controls Matrix. Even the Motion Picture Association of America has defined a cybersecurity framework to protect their member's intellectual property.

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework consists of five “functions,” which are: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover, as shown in the following.

These five functions are subdivided into 22 categories—and then each category has multiple controls. One issue with the NIST framework is that a comprehensive Security Assessment using this framework can quickly become a big project, often too big for the organization's size.

For small and medium-sized business, a good step forward is to specify the Center for Internet Security (CIS) Top 20 controls as the framework the independent Cyber Security team will assess. The CIS Top 20 controls provide an easy to understand assessment tool that senior executives will understand.

Once the CIS controls are evaluated, the organization's security posture can be easily visualized using color coded infographics and risk score heat charts. Many Security Assessments include an evaluation of the business's people, process, and technology. There is no point in spending technology dollars if the existing corporate processes do not support their use. These decisions can be explored using Radar charts to visualize the cyber readiness of three metrics: people, process, and technology. Radar charts depict cybersecurity assessment scores in a circular chart with gradient ranking that shows executives the information they need to act on to enhance their security posture.

The term vulnerability assessment applies to a broad range of systems. For example, in the context of a disaster recovery plan, the vulnerability assessment would include the likelihood of flooding, earthquakes, and other potential disasters. In the digital sphere, a vulnerability assessment is an evaluation of an organization's cybersecurity weaknesses. This process includes identifying and prioritizing specific computer configuration issues that represent vulnerable aspects of an organization's computing platforms.

The Institute for Security and Open Methodologies (ISECOM; www.isecom.org/research/) publishes the Open-Source Security Testing Methodology Manual that documents the components of a vendor neutral approach to a wide range of assessment methods and techniques. A vulnerability assessment project typically includes the following:

- Inventory of computing assets and networked devices

- Ranking those resources in order of importance

- Identification of vulnerabilities and potential threats

- Risk assessment

- Prioritized remediation plan

A vulnerability assessment starts with an inventory of computer systems and other devices connected to the network. Once the items on the network have been enumerated, the network is scanned using an automated tool to look for vulnerabilities. There are two types of scans: credentialed and noncredentialed. A credentialed scan uses domain admin credentials to obtain detailed inventories of software applications on each of the computers. This method provides the security team with the information necessary to identify operating system versions and required patches.

Often, a company's website is an overlooked corporate asset for a vulnerability assessments. The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) maintains a list of the top-10 vulnerabilities most commonly found on websites. Surprisingly, many websites fail to properly implement user authentication and data input checking. These types of vulnerabilities have the potential to expose corporate data to anyone with Internet access. Performing a vulnerability assessment exposes these issues so they may be resolved.

The final output of a vulnerability assessment project is the prioritized remediation plan. This plan uses the results of the risk assessment to determine which vulnerabilities represent the greatest risk to the organization. The total list of vulnerabilities is often numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands. However, not all of the vulnerabilities are big problems requiring immediate attention. The prioritized remediation plan allows IT administrators to reduce corporate risk quickly by focusing on the most important weaknesses first.

InfoSec Penetration Testing

Penetration testing (“pen test”) is a technique used by information security (InfoSec) professionals to find weaknesses in an organization's InfoSec defenses. In a penetration test, authorized cybersecurity professionals play the hacker's role.

Penetration testing attempts to circumvent digital safeguards and involves the simulation of an attack by hackers or an internal bad actor. The same techniques used by hackers to attack companies every day are used. The results of a penetration test reveal (in advance) the vulnerabilities and weaknesses that could allow a malicious attacker to gain access to a company's systems and data.

Some techniques used include brute-force attacks, exploitation of unpatched systems, and password-cracking tools. Organizations hire InfoSec experts with specialized training credentials––such as Certified Ethical Hacker (CEH) and Offensive Security Certified Profession (OSCP)––to conduct authorized attempts to breach the organization's security safeguards. These experts begin the pen test by conducting reconnaissance, often creating an attack surface and Internet footprint analysis to passively identify exposures, risks, and gaps in security. Once potential vulnerabilities are identified, the penetration testing team initiates the exploit attempts using automated tools to probe websites, firewalls, and e-mail systems.

Successful exploits often involve multiple vulnerabilities, which are attacked over several days. Individually, none of the weaknesses are a wide-open door. However, when combined together by an expert penetration tester, the result is a snowball effect that provides the pen test expert with an initial foothold inside the network from which they can pivot and gain access to additional systems.

Penetration testing is a useful technique for evaluating the potential damage from a determined attacker, as well as assess the organizational risks posed. Most hackers and criminals go after low-hanging fruit––easy targets. Regular penetration tests ensure that the efforts required to gain access to internal networks are substantial. The result? Most hackers will give up after a few hours and move on to other targets that are not so well defended.

Cybersecurity Considerations and Approaches

By Robert Smallwood

Limitations of Perimeter Security

Traditionally, central computer system security has been primarily perimeter security—securing the firewalls and perimeters within which e-documents are stored and attempting to keep intruders out—rather than securing e-documents directly upon their creation. The basic access security mechanisms implemented, such as passwords, two-factor authentication, and identity verification, are rendered totally ineffective once the confidential e-documents or records are legitimately accessed by an authorized employee. The documents are usually bare and unsecured. This poses tremendous challenges if the employee is suddenly terminated, if the person is a rogue intent on doing harm, or if outside hackers are able to penetrate the secured perimeter. And, of course, it is common knowledge that they do it all the time. The focus should be on securing the documents themselves, directly.

Restricting access is the goal of conventional perimeter security, but it does not directly protect the information inside. Perimeter security protects information the same way a safe protects valuables; if safecrackers get in, the contents are theirs. There are no protections once the safe is opened. Similarly, if hackers penetrate the perimeter security, they have complete access to the information inside, which they can steal, alter, or misuse.61 The perimeter security approach has four fundamental limitations:

- Limited effectiveness. Perimeter protection stops dead at the firewall, even though sensitive information is sent past it and circulates around the Web, unsecured. Today's extended computing model and the trend toward global business means that business enterprises and government agencies frequently share sensitive information externally with other stakeholders, including business partners, customers, suppliers, and constituents.

- Haphazard protections. In the normal course of business, knowledge workers send, work on, and store copies of the same information outside the organization's established perimeter. Even if the information's new digital environment is secured by other perimeters, each one utilizes different access controls or sometimes no access control at all (e.g. copying a price list from a sales folder to a marketing folder; an attorney copying a case brief or litigation strategy document from a paralegal's case folder).

- Too complex. With this multiperimeter scenario, there are simply too many perimeters to manage, and often they are out of the organization's direct control.

- No direct protections. Attempts to create boundaries or portals protected by perimeter security, within which stakeholders (partners, suppliers, shareholders, or customers) can share information, cause more complexity and administrative overhead while they fail to protect the e-documents and data directly.62

Despite the current investment in e-document security, it is astounding that once information is shared today, it is largely unknown who will be accessing it tomorrow.

Defense in Depth

Defense in depth is an approach that uses multiple layers of security mechanisms to protect information assets and reduce the likelihood that rogue attacks can succeed.63 The idea is based on military principles that an enemy is stymied by complex layers and approaches compared to a single line. That is, hackers may be able to penetrate one or two of the defense layers, but multiple security layers increase the chances of catching the attack before it gets too far. Defense in depth includes a firewall as a first line of defense and also antivirus and anti-spyware software, identity and access management (IAM), hierarchical passwords, intrusion detection, and biometric verification. Also, as a part of an overall IG program, physical security measures are deployed, such as smartcard or even biometric access to facilities and intensive IG training and auditing.

Controlling Access Using Identity Access Management

IAM software can provide an important piece of the security solution. It aims to prevent unauthorized people from accessing a system and to ensure that only authorized individuals engage with information, including confidential e-documents.

Today's business environment operates in a more extended and mobile model, often including stakeholders outside of the organization. With this more complex and fluctuating group of users accessing information management applications, the idea of identity management has gained increased importance.

The response to the growing number of software applications using inconsistent or incompatible security models is strong identity management enforcement software. These scattered applications offer opportunities not only for identity theft but also for identity drag, where the maintenance of identities does not keep up with changing identities, especially in organizations with a large workforce. This can result in theft of confidential information assets by unauthorized or out-of-date access and even failure to meet regulatory compliance, which can result in fines and imprisonment.64

IAM—along with sharp IG policies—“manages and governs user access to information through an automated, continuous process.”65 Implemented properly, good IAM does keep access limited to authorized users while increasing security, reducing IT complexity, and increasing operating efficiencies.

Critically, “IAM addresses ‘access creep’ where employees move to a different department of business unit and their rights to access information fail to get updated” (emphasis added).66

In France in 2007, a rogue stock trader at Société Générale had in-depth knowledge of the bank's access control procedures from his job at the home office.67 He used that information to defraud the bank and its clients out of over €7 billion (over $10 billion). If the bank had implemented an IAM solution, the crime may not have been possible.

A robust and effective IAM solution provides for:

- Auditing. Detailed audit trails of who attempted to access which information, and when. Stolen identities can be uncovered if, for instance, an authorized user attempts to log in from more than one computer at a time.

- Constant updating. Regular reviews of access rights assigned to individuals, including review and certification for user access, an automated recertification process (attestation), and enforcement of IG access policies that govern the way users access information in respect to segregation of duties.

- Evolving roles. Role life cycle management should be maintained on a continuous basis, to mine and manage roles and their associated access rights and policies.

- Risk reduction. Remediation regarding access to critical documents and information.

Enforcing IG: Protect Files with Rules and Permissions

One of the first tasks often needed when developing an IG program that secures confidential information assets is to define roles and responsibilities for those charged with implementing, maintaining, and enforcing IG policies. Corollaries that spring from that effort get down to the nitty-gritty of controlling information access by rules and permissions.

Rules and permissions specify who (by roles) is allowed access to which documents and information, and even contextually, from where (office, home, travel), and at what times (work hours, or extended hours). Using the old policy of the need-to-know basis is a good rule of thumb to apply when setting up these access policies (i.e. only those who are at a certain level of the organization or are directly involved in certain projects are allowed access to confidential and sensitive information). The roles are relatively easy to define in a traditional hierarchical structure, but today's flatter and more collaborative enterprises present challenges.

To effectively wall off and secure information by management level, many companies and governments have put in place an information security framework—a model that delineates which levels of the organization have access to specific documents and databases as a part of implemented IG policy. This framework shows a hierarchy of the company's management distributed across a range of defined levels of information access. The US Government Protection Profile for Authorization Server for Basic Robustness Environments is an example of such a framework.

Challenge of Securing Confidential E-Documents

Today's various document and content management systems were not initially designed to allow for secure document sharing and collaboration while also preventing document leakage. These software applications were mostly designed before the invention and adoption of newer business technologies that have extended the computing environment. The introduction of cloud computing, mobile PC devices, smartphones, social media, and online collaboration tools all came after most of today's document and content management systems were developed and brought to market.

Thus, vulnerabilities have arisen that need to be addressed with other, complementary technologies. We need to look no further than the WikiLeaks incident and the myriad of other major security breaches resulting in document and data leakage to see that there are serious information security issues in both the public and private sectors.

Technology is the tool, but without proper IG policies and a culture of compliance that supports the knowledge workers following IG policies, any effort to secure confidential information assets will fail. An old IT adage is that even perfect technology will fail without user commitment.

Protecting Confidential E-Documents: Limitations of Repository-Based Approaches

Organizations invest billions of dollars in IT solutions that manage e-documents and records in terms of security, auditing, search, records retention and disposition, version control, and so on. These information management solutions are predominantly repository-based, including enterprise content management (ECM) systems and collaborative workspaces (for unstructured information, such as e-documents). With content or document repositories, the focus has always been on perimeter security—keeping intruders out of the network. But that provides only partial protection. Once intruders are in, they are in and have full access to confidential e-documents. For those who are authorized to access the content, there are no protections, so they may freely copy, forward, print, or even edit and alter the information.68

The glaring vulnerability in the security architecture of ECM systems is that few protections exist once the information is legitimately accessed.

These confidential information assets, which may include military plans, price lists, patented designs, blueprints, drawings, and financial reports, often can be printed, e-mailed, or faxed to unauthorized parties without any security attached.69

Also, in the course of their normal work processes, knowledge workers tend to keep an extra copy of the electronic documents they are working on stored at their desktop, or they download and copy them to a tablet or laptop to work at home or while traveling. This creates a situation where multiple copies of these e-documents are scattered about on various devices and media, which creates a security problem, since they are outside of the repository and no longer secured, managed, controlled, or audited.

It also creates records management issues in terms of the various versions that might be out there and determining which one is the official business record.

Apply Better Technology for Better Enforcement in the Extended Enterprise

Protecting E-Documents in the Extended Enterprise

Sharing e-documents and collaborating are essential in today's increasingly mobile and global world. Businesses are operating in a more distributed model than ever before, and they are increasingly sharing and collaborating not only with coworkers but also with suppliers, customers, and even at times competitors (e.g. in pharmaceutical research). This reality presents a challenge to organizations dealing in sensitive and confidential information.70

Basic Security for the Microsoft Windows Office Desktop

The first level of protection for e-documents begins with basic protections at the desktop level. Microsoft Office provides ways to password-protect Microsoft Office files, such as those created in Word and Excel, quickly and easily. Many corporations and government agencies around the world use these basic protections. A key flaw or caveat is that passwords used in protecting documents cannot be retrieved if they are forgotten or lost.

Where Do Deleted Files Go?

When you delete a file it is gone, right? Actually, it is not (with the possible exception of solid-state hard drives). For example, after a file is deleted in Windows, a simple undelete DOS command can bring back the file, if it has not been overwritten. That is because when files are deleted, they are not really deleted; rather, the space where they reside is marked for reuse and can be overwritten. If it is not yet overwritten, the file is still there. The same process occurs as drafts of documents are created and temp (for temporary) files are stored. The portions of a hard drive where deleted or temp files are stored can be overwritten. This is called unallocated space. Most users are unaware that deleted files and fragments of documents and drafts are stored temporarily on their computer's unallocated space. So it must be wiped clean and completely erased to ensure that any confidential documents or drafts are completely removed from the hard drive.

IG programs include the highest security measures, which means that an organization must have a policy that includes deleting sensitive materials from a computer's unallocated space and tests that verify such deletion actions are successful periodically.

Lock Down: Stop All External Access to Confidential E-Documents

Organizations are taking other approaches to stop document and data leakage: physically restricting access to a computer by disconnecting it from any network connections and forbidding or even blocking use of any ports. Although cumbersome, these methods are effective in highly classified or restricted areas where confidential e-documents are held. Access is controlled by utilizing multiple advanced identity verification methods, such as biometric means.

Secure Printing

Organizations normally expend a good amount of effort making sure that computers, documents, and private information are protected and secure. However, if your computer is hooked up to a network printer (shared by multiple knowledge workers), all of that effort might have been wasted.71

Some basic measures can be taken to protect confidential documents from being compromised as they are printed. You simply invoke some standard Microsoft Office protections, which allow you to print the documents once you arrive in the copy room or at the networked printer. This process varies slightly, depending on the printer's manufacturer. (Refer to the documentation for the printer for details.)

In Microsoft Office, there is an option in the Print Dialog Box for delayed printing of documents (when you physically arrive at the printer).

Serious Security Issues with Large Print Files of Confidential Data

According to Canadian output and print technology expert William Broddy, in a company's data center, a print file of, for instance, investment account statements or bank statements contains all the rich information that a hacker or malicious insider needs. It is distilled information down to the most important core data about customers, which has been referred to as data syrup since it has been boiled down and contains no mountains of extraneous data, only the culled, cleaned, essential data that gives criminals exactly what they need.72

What most managers are not aware of is that entire print files and sometimes remnants of them stay on the hard drives of high-speed printers and are vulnerable to security breaches. Data center security personnel closely monitor calls to their database. To extract as much data as is contained in print files, a hacker requires hundreds or even thousands of calls to the database, which sets off alerts by system monitoring tools. But retrieving a print file takes only one intrusion, and it may go entirely unnoticed. The files are sitting there; a rogue service technician or field engineer can retrieve them on a routine service call.

To help secure print files, specialized hardware devices designed to sit between the print server and the network and cloak server print files are visible only to those who have a cloaking device on the other end.

Organizations must practice good IG and have specific procedures to erase sensitive print files once they have been utilized. For instance, in the example of preparing statements to mail to clients, files are exposed to possible intrusions in at least six points in the process (starting with print file preparation and ending with the actual mailing). These points must be tightly monitored and controlled. Typically an organization retains a print file for about 14 days, though some keep files long enough for customers to receive statements in the mail and review them. Organizations must make sure that print files or their remnants are secured and then completely erased when the printing job is finished.

E-Mail Encryption