CHAPTER 8

Information Governance and Legal Functions

Robert Smallwood with Randy Kahn, Esq., and Barry Murphy

Perhaps the key functional area that information governance (IG) impacts most is legal functions, since legal requirements are paramount. Failure to meet them can literally put an organization out of business or land executives in prison. Privacy, security, records management, information technology (IT), and business management functions are important—very important—but the most significant aspect of all of these functions relates to legality and regulatory compliance.

Key legal processes include electronic discovery (e-discovery) readiness and associated business processes, information and record retention policies, the legal hold notification (LHN) process, and legally defensible disposition practices.

Some newer technologies have become viable to assist organizations in implementing their IG efforts, namely, predictive coding and technology-assisted review (TAR; also known as computer-assisted review). In this chapter we cover the 2006 and 2015 changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP), explore the need for leveraging IT in IG efforts aimed at defensible disposition, the intersection between IG processes and legal functions, policy implications, and some key enabling technologies.

Introduction to E-Discovery: The Revised 2006 and 2015 Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Changed Everything

Since 1938, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure “have governed the discovery of evidence in lawsuits and other civil cases.”1 In law, discovery is an early phase of civil litigation where plaintiffs and defendants investigate and exchange evidence and testimony to better understand the facts of a case and to make early determinations of the strength of arguments on either side. Each side must produce evidence requested by the opposition or show the court why it is unreasonable to produce the information. As the Supreme Court stated in an early case under the Federal rules, “Mutual knowledge of all the relevant facts gathered by both parties is essential to proper litigation” (Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495, 507 (1947)).

The FRCP apply to US district courts, which are the trial courts of the federal court system. The district courts have jurisdiction (within limits set by Congress and the Constitution) to hear nearly all categories of federal cases, including civil and criminal matters.2

The FRCP were substantially amended in 2006, and further modified in 2015, specifically to address issues pertaining to the preservation and discovery of electronic records in the litigation process.3 These changes were a long time coming, reflecting the lag between the state of technology and the courts’ ability to catch up to the realities of electronically generated and stored information.

After years of applying traditional paper-based discovery rules to e-discovery, amendments to the FRCP were made to accommodate the modern practice of discovery of electronically stored information (ESI). ESI is any information that is created or stored in electronic format. The goal of the 2006 FRCP amendments was to recognize the importance of ESI and to respond to the increasingly prohibitive costs of document review and protection of privileged documents. These amendments reinforced the importance of IG policies, processes, and controls in the handling of ESI.4 Organizations must produce requested ESI reasonably quickly, and failure to do so, or failure to do so within the prescribed time frame, can result in sanctions. This requirement dictates that organizations put in place IG policies and procedures to be able to produce ESI accurately and in a timely fashion.5

All types of litigation are covered under the FRCP, and all types of e-documents—most especially e-mail—are included, which can be created, accessed, or stored in a wide variety of methods, and on a wide variety of devices beyond hard drives. The FRCP apply to ESI held on all types of storage and communications devices: thumb drives, CD/DVDs, smartphones, tablets, personal digital assistants (PDAs), personal computers, servers, zip drives, floppy disks, backup tapes, and other storage media. ESI content can include information from e-mail, reports, blogs, social media posts (e.g., Twitter posts), voicemails, wikis, Web sites (internal and external), word processing documents, and spreadsheets, and includes the metadata associated with the content itself, which provides descriptive information.6

Under the FRCP amendments, corporations must proactively manage the e-discovery process to avoid sanctions, unfavorable rulings, and a loss of public trust. Corporations must be prepared for early discussions on e-discovery with all departments. Topics should include the form of production of ESI and the methods for preservation of information. Records management and IT departments must have made available all relevant ESI for attorney review.7

This new era of ESI preservation and production demands the need for cross-functional collaboration: Records management, IT, and legal teams particularly need to work closely together. Legal teams, with assistance and input of records management staff, must identify relevant ESI, and IT teams must be mindful of preserving and protecting the ESI to maintain its legal integrity and prove its authenticity.

Big Data Impact

Now throw in the Big Data effect: the average employee creates roughly one gigabyte of data annually (and growing), and data volumes are expected to increase over the next decade not 10-fold, or even 20-fold, but as much as 40 to 50 times what it is today!8 This underscores the fact that organizations must meet legal requirements while paring down the mountain of data debris they are holding to reduce costs and potential liabilities hidden in that monstrous amount of information. There are also costs associated with dark data—useless data, such as old log files, that takes up space and continues to grow and needs to be cleaned up.

Some data is important and relevant, but distinctions must be made by IG policy to classify, prioritize, and schedule data for disposition and to dispose of the majority of it in a systematic, legally defensible way. If organizations do not accomplish these critical IG tasks they will be overburdened with storage and data handling costs and will be unable to meet legal obligations.

According to a survey by the Compliance, Governance, and Oversight Council (CGOC), approximately 25% of information stored in organizations has real business value, while 5% must be kept as business records and about 1% is retained due to a litigation hold.9 “This means that [about] 69 percent of information in most companies has no business, legal, or regulatory value. Companies that are able to [identify and] dispose of this debris return more profit to shareholders, can use more of their IT budgets for strategic investments, and can avoid excess expense in legal and regulatory response” (emphasis added).

If organizations are not able to draw clear distinctions between that roughly 30 percent of “high-value” business data, records, and that which is on legal hold, their IT department are tasked with the impossible job of managing all data as if it is high value. This “overmanaging” of information is a significant waste of IT resources.10

More Details on the Revised FRCP Rules

Here we present a synopsis of the key points in FRCP rules that apply to e-discovery.

- FRCP 1—Scope and Purpose. This rule is simple and clear; its aim is to have all rules construed by both courts and parties in litigation “to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action.”11 Your discovery effort and responses must be executed in a timely manner.

- FRCP 16—Pretrial Conferences; Scheduling; Management. This rule provides guidelines for preparing for and managing the e-discovery process; the court expects IT and network literacy on both sides, so that pretrial conferences regarding discoverable evidence are productive.

- FRCP 26—Duty to Disclose; General Provisions Governing Discovery. This rule protects litigants from costly and burdensome discovery requests, given certain guidelines.

- FRCP 26(a)(1)(C). Requires that you make initial disclosures no later than 14 days after the Rule 26(f) meet and confer, unless an objection or another time is set by stipulation or court order. If you have an objection, now is the time to voice it.

- Rule 26(b)(1). The rule as amended in 2015 expressly states that the scope of discovery must be proportional to the needs of the case, taking into account the importance of the issues at stake, the amount in controversy, the parties’ relative access to relevant information, the parties’ resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving issues, and whether the burden or expense of discovery outweighs its likely benefit. The rule allows parties responding to discovery to argue that in certain cases that discovery is unreasonably burdensome.

- Rule 26(b)(2)(B). Introduced the concept of not reasonably accessible ESI. The concept of not reasonably accessible paper had not existed. This rule provides procedures for shifting the cost of accessing not reasonably accessible ESI to the requesting party.

- Rule 26(b)(5)(B). Gives courts a clear procedure for settling claims when you hand over ESI to the requesting party that you shouldn't have.

- Rule 26(f). This is the meet and confer rule. This rule requires all parties to meet within 99 days of the lawsuit's filing and at least 21 days before a scheduled conference.

- Rule 26(g). Requires an attorney to sign every e-discovery request, response, or objection.

- FRCP 33—Interrogatories to Parties. This rule provides a definition of business e-records that are discoverable and the right of opposing parties to request and access them.

- FRCP 34—Producing Documents, Electronically Stored Information, and Tangible Things, or Entering onto Land, for Inspection and Other Purposes. In disputes over document production, this rule outlines ways to resolve and move forward. Specifically, FRCP 34(b) addresses the format for requests and requires that e-records be accessible without undue difficulty (i.e. the records must be organized and identified). The requesting party chooses the preferred format, which are usually native files (which also should contain metadata). The key point is that electronic files must be accessible, readable, and in a standard format.

- FRCP 37—Failure to Make Disclosures or to Cooperate; Sanctions. As amended in 2015, Rule 37(e) spells out a more uniform test for courts finding that curative measures or sanctions are appropriate to impose based on a party's failure to preserve ESI. If ESI should have been preserved but is lost due to a party's failure to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and it cannot be replaced, then upon a finding of prejudice a court may order measures to cure the prejudice. In the case of intentional misconduct, this may even include case-ending sanctions. This rule underscores the need for a legally defensible document management program under the umbrella of clear IG policies.

Landmark E-Discovery Case: Zubulake v. UBS Warburg

A landmark case in e-discovery arose from the opinions rendered in Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, an employment discrimination case where the plaintiff, Laura Zubulake, sought access to e-mail messages involving or naming her. Although UBS produced over 100 pages of evidence, it was shown that employees intentionally deleted some relevant e-mail messages.12 The plaintiffs requested copies of e-mail from backup tapes, and the defendants refused to provide them, claiming it would be too expensive and burdensome to do so.

The judge ruled that UBS had not taken proper care in preserving the e-mail evidence, and the judge ordered an adverse inference (assumption that the evidence was damaging) instruction against UBS. Ultimately, the jury awarded Zubulake over $29 million in total compensatory and punitive damages. “The court looked at the proportionality test of Rule 26(b)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and applied it to the electronic communication at issue. Any electronic data that is as accessible as other documentation should have traditional discovery rules applied.”13 Although Zubulake's award was later overturned on appeal, it is clear the stakes are huge in e-discovery and preservation of ESI.

E-Discovery Techniques

Current e-discovery techniques include online review, e-mail message archive review, and cyberforensics. Any and all other methods of seeking or searching for ESI may be employed in e-discovery. Expect capabilities for searching, retrieving, and translating ESI to improve, expanding the types of ESI that are discoverable. Consider this potential when evaluating and developing ESI management practices and policies.14

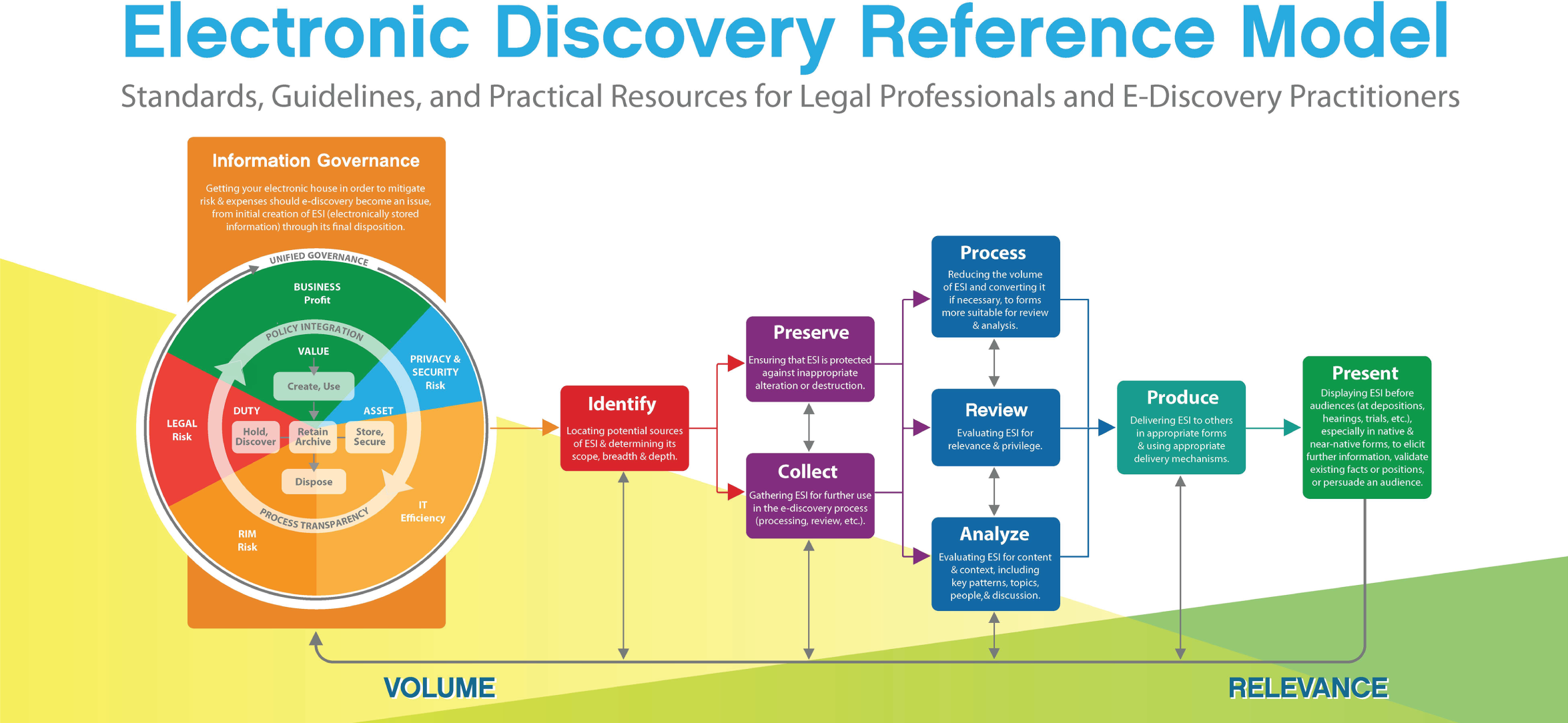

E-Discovery Reference Model

The E-Discovery Reference Model is a visual planning tool created by EDRM.net to assist in identifying and clarifying the stages of the e-discovery process. Figure 8.1 is the graphic depiction with accompanying detail on the process steps.

Figure 8.1 Electronic Discovery Reference Model

Source: EDRM (https://www.edrm.net/frameworks-and-standards/edrm-model/).

- Information governance. Getting your electronic house in order to mitigate risk and expenses should e-discovery become an issue, from initial creation of electronically stored information through its final disposition

- Identification. Locating potential sources of ESI and determining their scope, breadth, and depth

- Preservation. Ensuring that ESI is protected against inappropriate alteration or destruction

- Collection. Gathering ESI for further use in the e-discovery process (processing, review, etc.)

- Processing. Reducing the volume of ESI and converting it, if necessary, to forms more suitable for review and analysis

- Review. Evaluating ESI for relevance and privilege

- Analysis. Evaluating ESI for content and context, including key patterns, topics, people, and discussion

- Production. Delivering ESI to others in appropriate forms, and using appropriate delivery mechanisms

- Presentation. Displaying ESI before audiences (at depositions, hearings, trials, etc.), especially in native and near-native forms, to elicit further information, validate existing facts or positions, or persuade an audience15

The Electronic Discovery Reference Model can assist organizations in focusing and segmenting their efforts when planning e-discovery initiatives.

Guidelines for E-Discovery Planning

- Implement an IG program. The highest impact area to focus are your legal processes, particularly e-discovery. From risk assessment to processes, communications, training, controls, and auditing, fully implement IG to improve and measure compliance capabilities.

- Inventory your ESI. File scanning and e-mail archiving software can assist you. You also will want to observe files and data flows by doing a walk-through beginning with centralized servers in the computer room and moving out into business areas. Then, using a prepared inventory form, you should interview users to find out more detail. Be sure to inventory ESI based on computer systems or applications, and diagram it out.

- Create and implement a comprehensive records retention policy, and also include an e-mail retention policy and retention schedules for major ESI areas. This is required since all things are potentially discoverable. You must devise a comprehensive retention and disposition policy that is legally defensible. So, for instance, if your policy is to destroy all e-mail messages that do not have a legal hold (or are expected to) after 120 days, and apply that policy uniformly, you will be able to defend the practice in court. Also, implementing the retention policy reduces your storage burden and costs while cutting the risk of liability that might be buried in obscure e-mail messages.

- As an extension of your retention policy, implement a legal hold policy that is enforceable, auditable, and legally defensible. Be sure to include all potentially discoverable ESI. We discuss legal holds in more depth later in this chapter, but be sure to cast a wide net when developing retention policies so that you include all relevant electronic records, such as e-mail, e-documents and scanned documents, storage discs, and backup tapes.

- Leverage technology. Bolster your e-discovery planning and execution efforts by deploying enabling technologies, such as e-mail archiving, advanced enterprise search, TAR, and predictive coding.

- Develop and execute your e-discovery plan. You may want to begin from this point forward with new cases, and bear in mind that starting small and piloting is usually the best course of action.

The Intersection of IG and E-Discovery

By Barry Murphy

Effective IG programs can alleviate e-discovery headaches by reducing the amount of information to process and review, allowing legal teams to get to the facts of a case quickly and efficiently, and can even result in better case outcomes. Table 8.1 shows the impact of IG on e-discovery, by function.

Table 8.1 IG Impact on E-Discovery

Source: Barry Murphy.

| Impact | Function |

| Cost reduction | Reduce downstream costs of processing and review by defensibly disposing of data according to corporate retention policies Reduce cost of collection by centralizing collection interface to save time Keep review costs down by prioritizing documents and assigning to the right level associates (better resource utilization) Reduce cost of review by culling information with advanced analytics |

| Risk management | Reduce risk of sanctions by managing the process of LHN and the collection and preservation of potentially responsive information |

| Better litigation win rates | Optimize decision making (e.g. settling cases that can't be won) quickly with advanced analytics that prioritize hot documents Quickly find the necessary information to win cases with advanced searches and prioritized review |

| Strategic planning for matters based on merit | Determine the merits of a matter quickly and decide if it is a winnable case Quickly route prioritized documents to the right reviewers via advanced analytics (e.g., clustering) |

| Strategic planning for matters based on cost | Quickly determine how much litigation will cost via early access to amount of potentially responsive information and prioritized review to make decisions based on the economics of the matter (e.g. settle for less than the cost of litigation) |

| Litigation budget optimization | Minimize litigation budget by only pursuing winnable cases Minimize litigation budget by utilizing the lowest cost resources possible while putting high-cost resource on only the necessary documents |

Legal Hold Process

The legal hold process is a foundational element of IG.16 The way the legal hold process is supposed to work is that a formal system of polices, processes, and controls is put in place to notify key employees of a civil lawsuit (or impending one) and the set of documents that must put on legal hold. These documents, e-mail messages, and other relevant ESI must be preserved in place and no longer edited or altered so that they may be reviewed by attorneys during the discovery phase of the litigation. But, in practice, this is not always what takes place. In fact, the opposite can take place—employees can quickly edit or even delete relevant e-documents that may raise questions or even implicate them. This is possible only if proper IG controls are not in place, monitored, enforced, and audited.

Many organizations start with Legal Hold Notification (LHN). LHN management as a very discrete IG project. LHN management is arguably the absolute minimum an organization should be doing in order to meet the guidelines provided by court rules, common law, and case law precedent. It is worth noting, though, that the expectation is that organizations should connect the notification process to the actual collection and preservation of information in the long term.

How to Kick-Start Legal Hold Notification

Implementing an LHN program attacks some of the lower-hanging fruit within an organization's overall IG position. This part of the e-discovery life cycle must not be outsourced. Retained counsel provides input, but the mechanics of LHN are managed and owned by internal corporate resources.

In preparing for a LHN implementation project, it is important to first lose the perception that LHN tools are expensive and difficult to deploy. It is true that some of these tools cost considerably more than others and can be complex to deploy; however, that is because the tools in question go far beyond simple LHN and reach into enterprise systems and also handle data mapping, collection, and work flow processes. Other options include Web-based hosted solutions, custom-developed solutions, or processes using tools already in the toolbox (e.g. e-mail, spreadsheets, word processing).

The most effective approach involves three basic steps:

- Define requirements.

- Define the ideal process.

- Select the technology.

Defining both LHN requirements and processes should include input from key stakeholders—at a minimum—in legal, records management, and IT. Be sure to take into consideration the organization's litigation profile, corporate culture, and available resources as part of the requirements and process defining exercise. Managing steps 1 and 2 thoroughly makes tool selection easier because defining requirements and processes creates the confidence of knowing exactly what the tool must accomplish.

IG and E-Discovery Readiness

Having a solid IG underpinning means that your organization will be better prepared to respond and execute key tasks when litigation and the e-discovery process proceed. Your policies will have supporting business processes, and clear lines of responsibility and accountability are drawn. The policies must be reviewed and fine-tuned periodically, and business processes must be streamlined and continue to aim for improvement over time.

In order for legal hold or defensible deletion (discussed in detail in the next section—disposing of unneeded data, e-documents, and reports based on set policy) projects to deliver the promised benefit to e-discovery, it is important to avoid the very real roadblocks that exist in most organization. To get the light to turn green at the intersection of e-discovery and IG, it is critical to:

- Establish a culture that both values information and recognizes the risks inherent in it. Every organization must evolve its culture from one of keeping everything to one of information compliance. This kind of change requires high-level executive support. It also requires constant training of employees about how to create, classify, and store information. While this advice may seem trite, many managers in leading organizations say that without this kind of culture change, IG projects tend to be dead on arrival.

- Create a truly cross-functional IG team. Culture change is not easy, but it can be even harder if the organization does not bring all stakeholders together when setting requirements for IG. Stakeholders include: legal; security and ethics; IT; records management; internal audit; corporate governance; human resources; compliance; and business units and employees. That is a lot of stakeholders. In organizations that are successfully launching and executing IG projects, many have dedicated IG teams. Some of those IG teams are the next generation of records management departments while others are newly formed. The stakeholders can be categorized into three areas: legal/risk, IT, and the business. The IG team can bring those areas together to ensure that any projects meet requirements of all stakeholders.

- Use e-discovery as an IG proof of concept. Targeted programs like e-discovery, compliance, and archiving have history of return on investment (ROI) and an ability to get budget. These projects are also challenging, but more straightforward to implement and can address subsets of information in early phases (e.g. only those information assets that are reasonable to account for). The lessons learned from these targeted projects can then be applied to other IG initiatives.

- Measure ROI on more than just cost savings. Yes, one of the primary benefits of addressing e-discovery via IG is cost reduction, but it is wise to begin measuring all e-discovery initiatives on how they impact the life cycle of legal matters. The efficiencies gained in collecting information, for example, have benefits that go way beyond reduced cost; the IT time not wasted on reactive collection is more time available for innovative projects that drive revenue for companies. And a better litigation win rate will make any legal team happier.

Building on Legal Hold Programs to Launch Defensible Disposition

By Barry Murphy

Defensible deletion programs can build on legal hold programs, because legal hold management is a necessary first step before defensibly deleting anything. The standard is “reasonable effort” rather than “perfection.” Third-party consultants or auditors can support the diligence and reasonableness of these efforts.

Next, prioritize what information to delete and what information the organization is capably able to delete in a defensible manner. Very few organizations are deleting information across all systems. It can be overly daunting to try to apply deletion to all enterprise information. Choosing the most important information sources—e-mail, for example—and attacking those first may make for a reasonable and tenable approach. For most organizations, e-mail is the most common information source to begin deleting. Why e-mail? It is fairly easy for companies to put systematic rules on e-mail because the technology is already available to manage e-mail in a sophisticated manner. Because e-mail is such a critical data system, e-mail providers and e-mail archiving providers early on provided for systematic deletion or application of retention rules. However, in non–e-mail systems, the retention and deletion features are less sophisticated; therefore, organizations do not systematically delete across all systems.

Once e-mail is under control, the organization can begin to apply lessons learned to other information sources and eventually have better IG policies and processes that treat information consistently based on content rather than on the repository.

Destructive Retention of E-Mail

A destructive retention program is an approach to e-mail archiving where e-mail messages are retained for a limited time (say, 90 days), followed by the permanent manual or automatic deletion of the messages from the organization network, so long as there is no litigation hold or the e-mail has not been declared a record.

E-mail retention periods can vary from 90 days to as long as seven years:

- Osterman Research reports that “nearly one-quarter of companies delete e-mail after 90 days.”

- Heavily regulated industries, including energy, technology, communications, and real estate, favor archiving for one year or more, according to Fulbright and Jaworski research.

- The most common e-mail retention period traditionally has been seven years; however, some organizations are taking a hard-line approach and stating that e-mails will be kept for only 90 days or six months, unless it is declared as a record, classified, and identified with a classification/retention category and tagged or moved to a repository where the integrity of the record is protected (i.e. the record cannot be altered and an audit trail on the history of the record's usage is maintained).

Newer Technologies That Can Assist in E-Discovery

Few newer technologies are viable for speeding the document review process and improving the ability to be responsive to court-mandated requests. Here we introduce predictive coding and technology-assisted review (also known as computer-assisted review), the most significant of new technology developments that can assist in e-discovery.

Predictive Coding

During the early case assessment (ECA) phase of e-discovery, predictive coding is a “court-endorsed process”17 utilized to perform document review. It uses human expertise and IT to facilitate analysis and sorting of documents. Predictive coding software leverages human analysis when experts review a subset of documents to “teach” the software what to look for, so it can apply this logic to the full set of documents,18 making the sorting and culling process faster and more accurate than solely using human review or automated review.

Predictive coding uses a blend of several technologies that work in concert:19 software that performs machine learning (a type of artificial intelligence software that “learns” and improves its accuracy, fostered by guidance from human input and progressive ingestion of data sets—in this case documents);20workflow software, which routes the documents through a series of work steps to be processed; and text analytics software, used to perform functions such as searching for keywords (e.g., “asbestos” in a case involving asbestos exposure). Then, the next step is using keyword search capabilities, or concepts using pattern search or meaning-based search, and sifting through and sorting documents into basic groups using filtering technologies, based on document content, and sampling a portion of documents to find patterns and to review the accuracy of filtering and keyword search functions.

The goal of using predictive coding technology is to reduce the total group of documents a legal team needs to review manually (viewing and analyzing them one by one) by finding that gross set of documents that is most likely to be relevant or responsive (in legalese) to the case at hand. It does this by automating, speeding up, and improving the accuracy of the document review process to locate and “digitally categorize” documents that are responsive to a discovery request.21 Predictive coding, when deployed properly, also reduces billable attorney and paralegal time and therefore the costs of ECA. Faster and more accurate completion of ECA can provide valuable time for legal teams to develop insights and strategies, improving their odds for success. Skeptics claim that the technology is not yet mature enough to render more accurate results than human review.

The first state court ruling allowing the use of predictive coding technology instead of human review to cull through approximately two million documents to “execute a first-pass review” was made in April 2012 by a Virginia state judge.22 This was the first time a judge was asked to grant permission without the two opposing sides first coming to an agreement. The case, Global Aerospace, Inc., et al. v. Landow Aviation, LP, et al., stemmed from an accident at Dulles Jet Center.

This was the first big legal win for predictive coding use in e-discovery.

Basic Components of Predictive Coding

Here is a summary of the main foundational components of predictive coding.

- Human review. Human review is used to determine which types of document content will be legally responsive based on a case expert's review of a sampling of documents. These sample documents are fed into the system to provide a seed set of examples.24

- Text analytics. This involves the ability to apply “keyword-agnostic” (through a thesaurus capability based on contextual meaning, not just keywords) to locate responsive documents and build create seed document sets.

- Workflow. Software is used to route e-documents through the processing steps automatically to improve statistical reliability and streamlined processing.

- Machine learning. The software “learns” what it is looking for and improves its capabilities along the way through multiple, iterative passes.

- Sampling. Sampling is best applied if it is integrated so that testing for accuracy is an ongoing process. This improves statistical reliability and therefore defensibility of the process in court.

Predictive Coding Is the Engine; Humans Are the Fuel

Predictive coding sounds wonderful, but it does not replace the expertise of an attorney; it merely helps leverage that knowledge and speed the review process. It “takes all the documents related to an issue, ranks and tags them so that a human reviewer can look over the documents to confirm relevance.” So it cannot work without human input to let the software know what documents to keep and which ones to discard, but it is an emerging technology tool that will play an increasingly important role in e-discovery.25

Technology-Assisted Review

TAR, also known as computer-assisted review, is not predictive coding. TAR includes aspects of the nonlinear review process, such as culling, clustering and de-duplication, but it does not meet the requirements for comprehensive predictive coding.

Many technologies can help in making incremental reductions in e-discovery costs. Only fully integrated predictive coding, however, can completely transform the economics of e-discovery.

Mechanisms of Technology-Assisted Review

There are three main mechanisms, or methods, for using technology to make legal review faster, less costly, and generally smarter.26

- Rules driven. “I know what I am looking for and how to profile it.” In this scenario, a case team creates a set of criteria, or rules, for document review and builds what is essentially a coding manual. The rules are fed into the tool for execution on the document set. For example, one rule might be to “redact for privilege any time XYZ term appears and add the term ‘redacted’ where the data was removed.” This rule-driven approach requires iteration to truly be effective. The case team will likely have rules changes and improvements as the case goes on and more is learned about strategy and merit. This approach assumes that the case team knows the document set well and can apply very specific rules to the corpus in a reasonable fashion.

- Facet driven. “I let the system show me the profile groups first.” In this scenario, a tool analyzes documents for potential items of interest or groups potentially similar items together so that reviewers can begin applying decisions. Reviewers typically utilize visual analytics that guide them through the process and take them to prioritized documents. This mechanism can also be called present and direct.

- Propagation based. “I start making decisions and the system looks for similar-related items.” This type of TAR is about passing along, or propagating, what is known based on a sample set of documents to the rest of the documents in a corpus. In the market, this is often referred to as predictive coding because the system predicts whether documents will be responsive or privileged based on how other documents were coded by the review team. Propagation-based TAR comes in different flavors, but all involve an element of machine learning. In some scenarios, a review team will have access to a seed set of documents that the team codes and then feeds into the system. The system then mimics the action of the review team as it codes the remainder of the corpus. In other scenarios, there is not a seed set; rather, the systems give reviewers random documents for coding and then create a model for relevance and nonrelevance. It is important to note that propagation-based TAR goes beyond simple mimicry; it is about creating a linguistic mathematical model for what relevance looks like.

These TAR mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. In fact, combining the mechanisms can help overcome the limitations of individual approaches. For example, if a document corpus is not rich (e.g. does not have a high enough percentage of relevant documents), it can be hard to create a seed set that will be a good training set for the propagation-based system. However, it is possible to use facet-based TAR—for example, concept searching—to more quickly find the documents that are relevant so as to create a model for relevance that the propagation-based system can leverage.27

It is important to be aware that these approaches require more than just technology. It is critical to have the right people in place to support the technology and the workflow required to conduct TAR. Organizations looking to exercise these mechanisms of TAR will need:

- Experts in the right tools and information retrieval. Software is an important part of TAR. The team executing TAR will need someone that can program the tool set with the rules necessary for the system to intelligently mark documents. Furthermore, information retrieval is a science unto itself, blending linguistics, statistics, and computer science. Anyone practicing TAR will need the right team of experts to ensure a defensible and measurable process.

- Legal review team. While much of the chatter around TAR centers on its ability to cut lawyers out of the review process, the reality is that the legal review team will become more important than ever. The quality and consistency of the decisions this team makes will determine the effectiveness that any tool can have in applying those decisions to a document set.

- Auditor. Much of the defensibility and acceptability of TAR mechanisms will rely on the statistics behind how certain the organization can be that the output of the TAR system matches the input specification. Accurate measures of performance are important not only at the end of the TAR process, but also throughout the process in order to understand where efforts need to be focused in the next cycle or iteration. Anyone involved in setting or performing measurements should be trained in statistics.

For an organization to use a propagated approach, in addition to people it may need a “seed” set of known documents. Some systems use random samples to create seed sets while others enable users to supply small sets from the early case investigations. These documents are reviewed by the legal review team and marked as relevant, privileged, and so on. Then, the solution can learn from the seed set and apply what it learns to a larger collection of documents. Often this seed set is not available, or the seed set does not have enough positive data to be statistically useful.

Professionals using TAR state that the practice has value, but it requires a sophisticated team of users (with expertise in information retrieval, statistics, and law) who understand the potential limitations and danger of false confidence that can arise from improper use. For example, using a propagation-based approach with a seed set of documents can have issues when less than 10% of the seed set documents are positive for relevance. In contrast, rules driven and other systems can result in false negative decisions when based on narrow custodian example sets.

However TAR approaches and tools are used, they will only be effective if usage is anchored in a thought out, methodically sound process. This requires a definition of what to look for, searching for items that meet that definition, measuring results, and then refining those results on the basis of the measured results. Such an end-to-end plan will help to decide what methods and tools should be used in a given case.28

Defensible Disposal: The Only Real Way to Manage Terabytes and Petabytes

By Randy Kahn, Esq.

Records and information management (RIM) is not working. At least, it is not working well. Information growth and management complexity has meant that the old records retention rules and the ways businesses apply them are no longer able to address the life cycle of information. So the mountains of information grow and grow and grow, often unfettered.

Too much data has outlived its usefulness, and no one seems to know how or is willing to get rid of it. While most organizations need to right-size their information footprint by cleaning out the digital data debris, they are stymied by the complexity and enormity of the challenge.

Growth of Information

According to International Data Corporation (IDC, from now until 2020, the digital universe is expected by expand to more than 14 times its current size.29 One exabyte is the data equivalent of about 50,000 years of DVD movies running continuously. With about 1,800 exabytes of new data created in 2011, 2840 exabytes in 2012, and a predicted 6,120 exabytes in 2014, the volumes are truly staggering. While the data footprint grows significantly each year, that says nothing of what has already been created and stored.

Contrary to what many say (especially hardware salespeople) storage is not cheap. In fact, it becomes quite expensive when you add up not only the hardware costs but also maintenance, air conditioning, and space overhead, and the highly skilled labor needed to keep it running. Many large companies spend tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars per year just to store data. This is money that could go straight to the bottom line if the unneeded data could be discarded. When you consider that most organizations’ information footprints are growing at between 20 and 50% per year and the cost of storage is declining by a few percentage points per year, in real terms they are spending way more this year than last to simply house information.

Volumes Now Impact Effectiveness

The law of diminishing returns applies to information growth. Assuming information is an asset, at some point when there is so much data, its value starts to decline. That is not because the intrinsic value goes down (although many would argue there is a lot of idle chatter in the various communications technologies). Rather the decline is related to the inability to expeditiously find or have access to needed business information. According the Council of Information Auto-Classification “Information Explosion” Survey, there is now so much information that nearly 50% of companies need to re-create business records to run their business and protect their legal interests because they cannot find the original retained record.30 It is a poor business practice to spend resources to retain information and then, when it cannot be found, to spend more to reconstitute it.

There is increasing regulatory pressure, enforcement, and public scrutiny on all of an organization's data storage activities. Record sanctions and fines, new regulations, and stunning court decisions have converged to mandate heightened controls and accountability from government regulators, industry and standards groups as well as the public. When combined with the volume of data, information privacy, security, protection of trade secrets, and records compliance become complex and critical, high-risk business issues that only executive management can truly fix. However, executives typical view records and information management (RIM) as a low-importance cost center activity, which means that the real problem does not get solved.

In most companies, there is no clear path to classify electronic records, to formally manage official records, or to ensure the ultimate destruction of these records. Vast stores of legacy data are unclassified, and most data is never touched again shortly after creation. Further, traditional records retention rules are too voluminous, too complex, and too granular and do not work well with the technology needed to manage records.

Finally, it is clear that employees can no longer be expected to pull the oars to cut through the information ocean, let alone boil it down into meaningful chunks of good information. Increasingly, technology has to play a more central role in managing information. Better use of technology will create business value by reducing risk, driving improvements in productivity, and facilitating the exploitation and protection of ungoverned corporate knowledge.

How Did This Happen?

Over the past several years, organizations have come to realize that the exposure posed by uncontrolled data growth requires emergency, reactive action, as seemingly no other viable approach exists. Faced with massive amounts of unknown unstructured data, many organizations have chosen to adopt a risk-averse save-everything policy. This approach has brought with it immediate repercussions:

- Inability to quickly locate needed business content buried in ill-managed file systems.

- Sharply increased storage costs, with some companies refusing to allocate any more storage to the business. The user reaction, out of necessity, is to store data wherever they can find a place for it. (Do not buy the argument that storage is cheap—everyone is spending more on storing unnecessary data, even if the per-gigabyte media cost has gone down.)

- Soaring litigation and discovery costs, as organizations have lost track of what is where, who owns it, and how to collect, sort, and process it.

- Buried intellectual property, trade secrets, personally identifiable information, and regulated content is subject to leakage and unauthorized deletion, and are a clear target for opposing counsel—or anyone who can access it.

- Lack of centralized policies and systems for the storage of records, which results in hard-to-manage record sites spread throughout the organization.

- The lack of a clear strategy for managing records that have long-term, rather than short-term, business, legal, and research value.

Information Glut in Organizations

- 71% of organizations surveyed have no idea of the content in their stored data.

- 58% of organizations are keeping information indefinitely.

- 79% of organizations say too much time and effort is spent manually searching and disposing of information.

- 58% of organizations still rely on employees to decide how to apply corporate policies.31

What Is Defensible Disposition, and How Will It Help?

A solution to the unmitigated data sprawl is to defensibly dispose of the business content that no longer has business or legal value to the organization. In the old days of records management, it was clear that courts and regulators alike understood that records came into being and eventually were destroyed in the ordinary course of business. It is good business practice to destroy unneeded content, provided that the rules on which those decisions are made consider legal requirements and business needs. Today, however, the good business practice of cleaning house of old records has somehow become taboo for some businesses. Now it needs to start again.

An understanding of how technology can help defensibly dispose and how methodology and process help an organization achieve a thinner information footprint is critical for all companies overrun with outdated records that do not know where to start to address the issue. While no single approach is right for every organization, records and legal teams need to take an informed approach, looking at corporate culture, risk tolerance, and litigation profile.

A defensible disposition framework is an ecosystem of technology, policies, procedures, and management controls designed to ensure that records are created, managed, and disposed at the end of their life cycle.

New Technologies—New Information Custodians

Responsibility for records management and IG has changed dramatically over time. In the past, the responsibility rested primarily with the records manager. However, the nature of electronic information is such that its governance today requires the participation of IT, which frequently has custody, control, or access to such data, along with guidance from the legal department. As a result, IT personnel with no real connection or ownership of the data may be responsible for the accuracy and completeness of the business-critical information being managed. See the problem?

For many organizations advances in technology mixed with an explosive growth of data forced a reevaluation of core records management processes. Many organizations have deployed archiving, litigation, and e-discovery point solutions with the intent of providing record retention compliance and responsiveness to litigation. Such systems may be tactically useful but fail to strategically address the heart of the matter: too much information, poorly managed over years and years—if not decades.

A better approach is for organizations to move away from a reactive keep-everything strategy to a proactive strategy that allows the reasonable and reliable identification and deletion of records when retention requirements are reached, absent a preservation obligation. Companies develop retention schedules and processes precisely for this reason; it is not misguided to apply them.

Why Users Cannot, Will Not—and Should Not—Make the Hard Choices

Employees usually are not sufficiently trained on records management principles and methods and have little incentive (or downside) to properly manage or dispose of records. Further, many companies today see that requiring users to properly declare or manage records places an undue burden on them. The employees not only do not provide a reasonable solution to the huge data pile (which for some companies may be petabytes of data) but contribute to its growth by using more unsanctioned technologies and parking company information in unsanctioned locations. This is how the digital landfill continues to grow.

Most organizations have programs that address paper records, but these same organizations commonly fail to develop similar programs for electronic records and other digital content.

Technology Is Essential to Manage Digital Records Properly

Having it all—but not being able to find it—is like not having it at all.

While the content of a paper document is obvious, viewing the content of an electronic document depends on software and hardware. Further, the content of electronic storage media cannot be easily accessed without some clue as to its structure and format. Consequently, the proper indexing of digital content is fundamental to its utility. Without an index, retrieving electronic content is expensive and time consuming, if it can be retrieved at all.

Search tools have become more robust, but they do not provide a panacea for finding electronic records when needed because there is too much information spread out across way too many information parking lots. Without taxonomies and common business terminology, accessing the one needed business record may be akin to finding the needle in a stadium-size haystack.

Technological advances can help solve the challenges corporations face and address the issues and burdens for legal, compliance. and information governance. When faced with hundreds of terabytes to petabytes of information, no amount of user intervention will begin to make sense of the information tsunami.

Auto-Classification and Analytics Technologies

Increasingly companies are turning to new analytics and classification technologies that can analyze information faster, better, and cheaper. These technologies should be considered essential for helping with defensible disposition, but do not make the mistake of underestimating their expense or complexity.

Machine learning technologies mean that software can “learn” and improve at the tasks of clustering files and assigning information (e.g. records, documents) to different preselected topical categories based on a statistical analysis of the data characteristics. In essence, classification technology evaluates a set of data with known classification mappings and attempts to map newly encountered data within the existing classifications. This type of technology should be on the list of considerations when approaching defensible disposition in large, uncontrolled data environments.

Can Technology Classify Information?

What is clear is that IT is better and faster than people in classifying information. Period.

Increasingly studies and court decisions make clear that, when appropriate, companies should not fear using enabling technologies to help manage information.

For example, in the recent Da Silva Moore v. Publicis Groupe case, Judge Andrew Peck stated:

Computer-assisted review appears to be better than the available alternatives, and thus should be used in appropriate cases. While this Court recognizes that computer-assisted review is not perfect, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not require perfection…. Counsel no longer have to worry about being the “first” or “guinea pig” for judicial acceptance of computer assisted review.

This work presents evidence supporting the contrary position: that a technology-assisted process, in which only a small fraction of the document collection is ever examined by humans, can yield higher recall and/or precision than an exhaustive manual review process, in which the entire document collection is examined and coded by humans.32

Moving Ahead by Cleaning Up the Past

Organizations can improve disposition and IG programs with a systemized, repeatable, and defensible approach that enables them to retain and dispose of all data types in compliance with the business and statutory rules governing the business's operations.

Generally, an organization is under no legal obligation to retain every piece of information it generates in the course of its business. Its records management process is there to clean up the information junk in a consistent, reasonable way. That said, what should companies do if they have not been following disposal rules, so information has piled up and continues unabated? They need to clean up old data. But how?

Manual intervention (by employees) will likely not work, due to the sheer volumes of data involved. Executives will not and should not have employees abdicate their regular jobs in favor of classifying and disposing of hundreds of millions of old stored files. (Many companies have billions of old files.) This buildup necessitates leveraging technology, specifically, technologies that can discern the meaning of stored unstructured content, in a variety of formats, regardless of where it is stored.

Here is a starting point: most likely, file shares, legacy e-mail systems, and other large repositories will prove the most target-rich environments, while better-managed document management, records management, or archival systems will be in less need of remediation. A good time to undertake a cleanup exercise is when litigation will not prevent action or when migrating to a new IT platform. (Trying to conduct a comprehensive, document-level inventory and disposition is neither reasonable nor practical. In most cases, it will create limited results and even further frustration.)

Technology choices should be able to withstand legal challenges in court. Sophisticated technologies available today should also look beyond mere keyword searches (as their defensibility may be called into question) and should look to advanced techniques such as automatic text classification (auto-classification), concept search, contextual analysis, and automated clustering. While technology is imperfect, it is better than what employees can do and will never be able to accomplish—to manage terabytes of stored information and clean up big piles of dead data.

Defensibility Is the Desired End State; Perfection Is Not

Defensible disposition is a way to take on huge piles of information without personally cracking each one open and evaluating it. Perhaps it is, in essence, operationalizing a retention schedule that is no longer viable in the electronic age. Defensible disposition is a must because most big companies have hundreds of millions or billions of files, which makes their individualized management all but impossible.

As the list of eight steps to defensible disposition makes clear, different chunks of data will require different diligence and analysis levels. If you have 100,000 backup tapes from 20 years ago, minimal or cursory review may be required before the whole lot of tapes can be comfortably discarded. If, however, you have an active shared drive with records and information that is needed for ongoing litigation, there will need to be deeper analysis with analytics and/or classification technologies that have become much more powerful and useful. In other words, the facts surrounding the information will help inform if the information can be properly disposed with minimal analysis or if it requires deep diligence.

Kahn's Eight Essential Steps to Defensible Disposition

- Define a reasonable diligence process to assess the business needs and legal requirements for continued information retention and/or preservation, based on the information at issue.

- Select a practical information assessment and/or classification approach, given information volumes, available resources, and risk profile.

- Develop and document the essential aspects of the disposition program to ensure quality, efficacy, repeatability, auditability, and integrity.

- Develop a mechanism to modify, alter, or terminate components of the disposition process when required for business or legal reasons.

- Assess content for eligibility for disposition, based on business need, record retention requirements, and/or legal preservation obligations.

- Test, validate, and refine as necessary the efficacy of content assessment and disposition capability methods with actual data until desired results have been attained.

- Apply disposition methodology to content as necessary, understanding that some content can be disposed with sufficient diligence without classification.

- On an ongoing basis, verify and document the efficacy and results of the disposition program and modify and/or augment the process as necessary.

Business Case Around Defensible Disposition

What is clear is that defensible disposition can have significant ROI impact to a company's financial picture. This author has clients for whom we have built the defensible disposition business case, which saves them tens of millions of dollars on a net basis but also makes them a more efficient business, reduces litigation cost and risks, mitigates the information security and privacy risk profiles, and makes their work force more productive, etc.

However, remember auto-classification technology is neither simple nor inexpensive, so be realistic and conservative when building the business case. Often it is easiest to simply use only hardware storage cost savings to make the case because it is a hard number and provides a conservative approach to justifying the activities. Then you can add on the additional benefits, which are more difficult to calculate, and also the intangible benefits of giving your employees a cleaner information stack to search and base decisions on.

Defensible Disposition Summary

Defensible disposition is a way to bring your records management program into today's business reality—information growth makes management at the record level all but impossible. Defensible disposition should be about taking simplified retention rules and applying them to both structured and unstructured content with the least amount of human involvement possible. While it can be a daunting challenge, it is also an opportunity to establish and promote operational excellence through better IG and to significantly enhance an organization's business performance and competitive advantage.

Notes

- 1. Linda Volonino and Ian Redpath, e-Discovery For Dummies (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), 9.

- 2. “New Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,” http://www.uscourts.gov/FederalCourts/Understanding-theFederalCourts/DistrictCourts.aspx (accessed November 26, 2013).

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Volonino and Redpath, e-Discovery For Dummies, p. 13.

- 6. Ibid., p. 11.

- 7. “New Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.”

- 8. “The Digital Universe Decade—Are You Ready?” IDC iView (May 2010). https://www.cio.com.au/campaign/370004?content=%2Fwhitepaper%2F370012%2Fthe-digital-universe-decade-are-you-ready%2F%3Ftype%3Dother%26arg%3D0%26location%3Dfeatured_list.

- 9. Deidra Paknad, “Defensible Disposal: You Can't Keep All Your Data Forever,” July 17, 2012, www.forbes.com/sites/ciocentral/2012/07/17/defensible-disposal-you-cant-keep-all-your-data-forever/.

- 10. Sunil Soares, Selling Information Governance to the Business (Ketchum, ID: MC Press Online, 2011), 229.

- 11. All quotations from the FRCP are from Volonino and Redpath, e-Discovery For Dummies, www.dummies.com/how-to/content/ediscovery-for-dummies-cheat-sheet.html (accessed May 22, 2013).

- 12. Linda Volonino and Ian Redpath, e-Discovery For Dummies (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), p. 11.

- 13. Case Briefs, LLC, “Zubulake v. UBS Warburg LLC,” http://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/civil-procedure/civil-procedure-keyed-to-friedenthal/pretrial-devices-of-obtaining-information-depositions-and-discovery-civil-procedure-keyed-to-friedenthal-civil-procedure-law/zubulake-v-ubs-warburg-llc/2/ (accessed May 21, 2013).

- 14. Amy Girst, “E-discovery for Lawyers,” IMERGE Consulting Report, 2008.

- 15. ECM2, “15-Minute Guide to eDiscovery and Early Case Assessment,” www.emc.com/collateral/15-min-guide/h9781-15-min-guide-ediscovery-eca-gde.pdf (accessed May 21, 2013).

- 16. Barry Murphy, telephone interview with author, April 12, 2013.

- 17. Recommind, “What Is Predictive Coding?” www.recommind.com/predictive-coding (accessed May 7, 2013).

- 18. Michael LoPresti, “What Is Predictive Coding?: Including eDiscovery Applications,” KMWorld, January 14, 2013, www.kmworld.com/Articles/Editorial/What-Is-…/What-is-Predictive-Coding-Including-eDiscovery-Applications-87108.aspx.

- 19. “Predictive Coding,” TechTarget.com, August 31, 2012, http://searchcompliance.techtarget.com/definition/predictive-coding (accessed May 7, 2013).

- 20. “Machine Learning,” TechTarget.com http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/machine-learning (accessed May 7, 2013).

- 21. “Predictive Coding.”

- 22. LoPresti, “What Is Predictive Coding?”

- 23. Ibid.

- 24. Recommind, “What Does Predictive Coding Require?” www.recommind.com/predictive-coding (accessed May 24, 2013).

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Barry Murphy, e-mail to author, May 10, 2013.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. Ibid.

- 29. “The Digital Universe in 2020: Big Data, Bigger Digital Shadows, and Biggest Growth in the Far East,” www.emc.com/collateral/analyst-reports/idc-the-digital-universe-in-2020.pdf (accessed November 26, 2013).

- 30. Council of Information Auto-Classification, “Information Explosion” survey, http://infoautoclassification.org/survey.php (accessed November 26, 2013).

- 31. Ibid.

- 32. Maura R. Grossman and Gordon V. Cormack, “Technology-Assisted Review in E-Discovery Can Be More Effective and More Efficient Than Exhaustive Manual Review.” http://delve.us/downloads/Technology-Assisted-Review-In-Ediscovery.pdf (accessed November 26, 2013).