CHAPTER 10

Post-Deal Integration

An M&A deal does not end with the completion of the transaction at closing, although very often that is when the public attention to the deal from outside the company largely disappears. It may therefore seem to outsiders that the deal is complete, but in most cases the closing of the deal is only the start of the truly hard work of making the newly formed company work.

In fact, once the deal is closed, post-deal integration is the only, and last, step responsible for realizing the value that was planned from the start. Therefore, the success of the previous phases (strategic planning, financial analysis, deal structuring, and negotiation) will typically depend upon a robust and dynamic post-deal integration plan and the successful implementation of that plan. As told to us by Giuseppe Monarchi, Managing Director and Head of Investment Banking and M&A Europe at Credit Suisse, “I feel that the well-known 7-Ps British Army adage [Proper Planning and Preparation Prevents Piss Poor Performance] applies very much to M&A, although I prefer to use the simpler 4Ps: preparation prevents poor performance.”

M&A is a means to an end – not just an end in itself. For companies using M&A as a tool to accomplish corporate objectives, post-deal integration should be carried out carefully with focus from the top of the organization and sound execution throughout. Unfortunately, in many deals the focus is exclusively on completing the deal and not enough attention is paid to the various organizational and people issues that will be faced after closing. This contributes to the high failure rate of M&A deals. There is also the tendency to focus on some of the seemingly bigger issues (such as the decision as to who will be CEO, the name of the company, and even the new logo). They forget that, according to a 2012 Capgemini study, areas such as IT integration may contribute more than 40% of the synergies in a merger and that the IT spend will likely have to increase by an average of 15% in the first few years as systems are merged.

Post-deal integration is the “quiet” phase of the typical merger as, to the outside world, there is usually very little discussion about the deal at this time; unless, of course, it is falling apart and was a high profile deal. It may be headline-grabbing “news” when two large firms announce their intention to combine in a merger or acquisition, and this is especially true when the transaction is hostile and competing bidders enter the fray. But once the deal is completed, the focus usually shifts to the internal. As post-deal integration is the most important phase of the deal, the lower level of public attention should not be considered a proxy for how critical this actually is to the merger's ultimate success or failure.

The success of the deal depends more upon the post-deal integration than any other single step in the M&A process. This is often misunderstood by many M&A practitioners and advisors, who believe that success will naturally follow when there has been a proper selection of the target, combined with the best price/valuation.

A merger will likely fail if it has the right strategic rationale but that strategy is implemented poorly; likewise, failure will follow a merger carried out at the best price but with bad post-deal integration. On the other hand, if a deal has no sound strategic rationale or if the strategy was based on circumstances that have since changed, and even if the deal was done for far too high a price, the newly combined firm can still be successful if there is effective and creative management of the new organization after the merger.

As we saw at the beginning of Chapter 1, most mergers have been failures: the simplest way to improve that track record is to focus on post-deal integration. The increase in attention on this phase since the turn of the millennium is already reflected in the higher rates of success since that time.

Change Management

The post-deal integration period is very similar in many ways to any strategic change management process for a company. As such, it must continually assess the speed of the changes being made (fast or slow, incremental or discontinuous), establish clear leadership, communicate effectively, maintain customer focus throughout the process, deal with resistance both internal and external, make and thus not defer tough decisions, and take initiatives focused on the end result. It must be dynamic, adapting to the ever-changing circumstances.

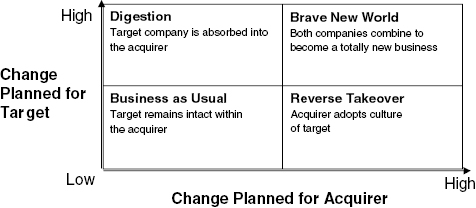

As acquisitions occur for different reasons, post-deal planning should reflect the change desired from the deal (see Figure 10.1). As will be discussed later, most deals fall into the top left corner where one (typically larger) company completely digests and absorbs the (typically much smaller) company. But it cannot be assumed that this is the case for all deals and, if the strategy behind the deal is unclear, then there is no reason for management to expect successful post-deal integration.

This is because different types of acquisition bring with them different post-deal problems. For example, a company dealing with overcapacity in a mature market will need to reduce costs quickly and will typically impose its own systems on the target (although willing to look for “best of breed” as the target may have some better systems). If a company is using acquisitions as a substitute for in-house R&D, as is common with many technology and pharmaceutical companies, then it will typically keep the research functions separate after the acquisition for a period but rapidly integrate other areas. Other deals are asset acquisitions, for which there is little need to factor in the human resource elements needed in a full integration. Each situation is unique. Different work streams will also vary in length of time: IT systems integration may take a year or two while client coverage and senior management changes, for example, may complete within the first 100 days.

Integration Costs

The costs of doing integration poorly can be immense. These costs are not just limited to the visible out-of-pocket quantifiable expenses of the deal, such as the rebranding of products and branches, printing new brochures and business cards, marketing campaigns, redundancy packages, and systems integration costs. As discussed in the valuation chapter, the overall cost also includes items that are very difficult to quantify but that will have a major impact on the newly merged company's bottom line. Some of these items include the following:

- Hiring and training new employees and existing employees in new positions.

- Time-consuming and distracting meetings and activities during integration (diverting focus from marketing, new product development, and other income-producing non-merger activities).

- Dysfunctional politicking and power fights.

- Decrease in employee efficiency during the period of uncertainty (one report in the Harvard Business Review in 2000 estimated that the efficiency of staff can decline by more than 80% in the immediate period following the announcement of a merger or acquisition).

- Customer confusion and competitors' attempts to poach clients during this period.

Integration Planning

Integration planning should begin at the deal idea-generation stage and continue throughout the merger process. When sound strategic and financial strategies that have combined to bring the merger or acquisition to fruition have been followed, they become the basis of post-deal integration. This planning is the first phase of integration, with post-closing execution being the second. These two stages necessarily overlap, as some execution can, in some deals, begin prior to closing.

Unfortunately, there are often very large disconnects between the various deal teams: those which developed the strategy, the financial team valuing the firms, the negotiation team, and then the team – the whole new organization – that must implement the integration. Many of the external advisors to the deal are also gone once the deal is completed (although a whole set of new advisors may have arrived) and even the internal planners may now be focused on the next deal. It is often left to the “new” managers themselves to implement what others have planned.

There are five major stages in the post-deal integration process, each with distinctive characteristics that must be handled differently. The first three stages take place during the first, pre-closing phase, while the last two usually take place after the deal has closed. Attention needs to be paid to all of the phases, because it is a gross error to assume, as many do, that pre-closing mistakes can be corrected by the post-deal integration.

Integration Phase One: Pre-closing

- Stage 1. High-level merger planning: discussion at the senior executive level which should be kept confidential; these discussions should include talks about how the companies can or will combine. The advisors for the post-deal period may be selected at this time. There are deals where no contact has yet been made with the target company, so this planning will need to be preliminary and flexible enough to change once the due diligence has been conducted internally in the target.

- Stage 2. Formal (or leaked) announcement: employees and management will have mixed emotions and expectations rise in many cases due to external discussion about the deal's potential. For some organizations, there can be relief once the deal has been announced, especially if the company had been in trouble and there had been rumors of a merger or a previous attempt at one that had fallen through. There is excitement from some, especially those who were engaged in the merger planning. Due to the natural uncertainty of most about the deal, it is important to be able to announce some integration plans at the same time, or within days of the deal announcement. Best practice would have the first level of management determined by the time the deal is announced (although this may not be possible if the deal leaks prematurely); ideally, each additional layer of management should be announced every six to eight weeks.

- Stage 3. Initial organizational change pre-closing: the two companies both know that they will combine, but the deal has not officially closed, so most of the integration cannot yet be started. Even before they become one company, the changes will have started. The organization is unstable and, although many employees have the best intentions to cooperate, goodwill may quickly erode because of uncertainty about many aspects of the post-deal end-state. Post-deal planning is now out in the open, with a need for the effective use of business intelligence. A large number of people, both internal and external, will be engaged in these planning efforts.

Integration Phase Two: Post-closing

- Stage 4. Post-deal integration: often intense during this period (typically for approximately 100 days post-closing) but with a high level of organizational instability, including “us vs. them” mentality and intra- and interdepartmental hostility. The newly combined company should have a well-developed post-deal plan, combined with the business intelligence techniques noted earlier. Problems can be anticipated but flexibility around the changing organization is important, even if a few major decisions have been “cast in concrete” so that employees and others have some indication of future stability.

- Stage 5. Psychological integration and organizational stabilization: roles and systems are by this point clarified and there have been successes demonstrating the power of the new organization. This is a long-term, gradual process which may take years to finalize, as some changes take a long time to realize. The end game is clear and employees, customers, and suppliers consider the combined companies to be “business as usual.” The company may now be planning the next deal.

Note that formal post-deal integration does not start until the deal is completed and closed (just prior to stage 4 above), but the planning for that post-deal period should be discussed from the very start, at stage 1.

These stages can take a varying amount of time to complete, and the last phase can still be unfinished as long as a decade after completion of the deal. For example, in a case we also saw in Chapter 1, Morgan Stanley took eleven years following its 1997 merger with Dean Witter finally to consolidate its two broker dealers into one, only dropping the Dean Witter name in April 2007. Even after successful integration, many companies still have employees who identify themselves years later as being from either one or the other original company.

Keys to Integration Success

A joint study by PA Consulting and the University of Edinburgh School of Management showed that when acquirers' integration followed what they defined as “best practice,” their share price returns were 3.6% above the value predicted had the acquisition not taken place. This demonstrates that there is value in this phase of a deal, and that success depends on more than identifying the right target companies and negotiating the best price (although both those factors can also contribute to a greater ability to achieve successful integration).

In order to achieve a successful post-deal integration – and thus the success of the whole deal – there are nine areas that require attention which will be discussed in more detail below:

- Communicate

- Leadership

- Engineer successes

- Advisors

- Nurture clients

- Retain key employees

- Adjust, plan, and monitor

- Integrate the two cultures

- Decide quickly

These can be remembered by a simple mnemonic: CLEAN RAID.

Communicate

The company's management and the integration team will need to make sure that there is adequate focus on communication. The communications must emanate from the very top of both organizations or else they run the risk of lacking credibility. Managers must “walk the talk” and show that they have recognized the changes to the organization and their impact on individual employees. The very senior managers can best communicate the vision of the deal and the related business logic.

To help drive the success of the deal, this communication should start with the deal announcement – in other words, well before post-deal integration starts. In one of our surveys released in 2014, two-thirds of successful acquirers publicly shared details of their new organizations post-deal, which helped to prevent unnecessary and often incorrect rumors and to mitigate the negative consequences of stress and anxiety on employees. Only one-third of acquirers in the failure group shared such information.

There is no best way to provide this type of communication, as each organization will have its own culture and existing communications tools. It could be in the form of hotlines, newsletters, presentations, and workshops. The informal lines of communication are potentially of greater importance and, although differing in each organization, ways should be found to exploit them.

No matter what methods are used to communicate, they must demonstrate transparency and openness at all times; a lack of candor or honesty will be immediately sensed by most employees, and the goodwill that is critical to have in place for the successful implementation of the deal will be destroyed. It is best to tell employees, communities, and other stakeholders everything that you can as early as you can, especially when the news is negative. Positive messages should be repeated. Management should recognize that their actions speak louder than words.

In a period when employees are uncertain about their future, it is better to over-communicate than wait for a time when there is something new to say. One of the worst statements for senior management to make around the time of the merger integration is: “We will tell you something when there is something new to tell.” The internal company gossip channels will be full of rumors, most of them false, especially when management itself has created a communication void that needs to be filled. The best way to stop these rumors is to communicate effectively and often, even at the risk of being repetitive.

One way to achieve success is to avoid some of the communications pitfalls that companies have fallen into in the past when merging or acquiring. The temptation to communicate in a way that placates staff is intense, yet can often backfire when reality appears. This is especially true if senior managers begin to believe the hype and spin of their own public communication statements: the press releases that they've issued through their public relations agencies, the presentations to investment banking industry analysts, and the memos sent by their internal communication teams.

In summary, communications were ineffective according to a Watson Wyatt (now Towers Watson) survey in 2008 because of inadequate resources applied to them, the communications campaign was either too slow or ended too early, senior management paid inadequate attention to the issue, not all groups were contacted during the campaign, the messages were inconsistent, or they were not well planned or too infrequent. This is a large number of issues to keep in mind just for communication, but that is why there needs to be adequate focus if deal success is to be achieved.

Leadership

It is important to set up the appropriate structure and organization for the post-deal integration, starting with the Leadership. The top of the company needs to be seen internally and externally as being focused on the success of the deal. It is the senior management of the company that must challenge decisions and assess the progress of integration. In an acquisition, this must be led by the acquiring company's management, by those most familiar with the culture and operations of the new owners. In fact, a study by Cass Business School's M&A Research Centre released in 2014 found that successful acquirers were quicker to remove and replace the target company's senior executive team: among successful acquirers, only 38% of CEOs and 19% of CFOs remained in post six months after completion, compared to 44% and 38% respectively in deals that ultimately failed.

The CEO needs to appoint an integration manager who comes from a high level in the organization, ensures middle management buy-in and involvement through the use of integration planning committees and task forces, and makes quick decisions on compensation where necessary (such as retention contracts). The CEO should be meeting with clients, suppliers, and analysts perhaps even more frequently than usual.

A single integration manager should be appointed, although some mergers have co-managers, with a senior individual from both companies, who together have responsibility for the integration. It is rare that the co-manager structure can work as efficiently as one manager; certainly this is not a long- or even mid-term solution.

Integration managers are needed to speed up the integration process, create a structure, forge social connections between the two organizations, and help engineer short-term successes. The integration manager should be identified, and should start the post-deal planning at the very outset of the deal process – even if it is not yet certain that it will be consummated. The earlier that the post-deal planning can start, the easier and more effective the post-deal integration will be. In fact, the integration manager should ideally be present at all of the major pre-merger planning meetings. Furthermore, this continuity of planning and implementation should be the process in all deals. Indeed, “where a deal does not have a champion, it can run into trouble,” a VP for Corporate Development at 3M Company, a very successful serial acquirer, told Mercer, the management consulting firm. “You need someone to own every deal; otherwise, it will not happen.”

Who would make the ideal integration manager? It is best if such an individual has deep knowledge of the acquiring company, is successful in his/her own career to date, does not need to take credit for the success of the deal, is comfortable with chaos, is willing to put in the long hours typically required, is trusted by senior management in the acquirer, has emotional and cultural intelligence, and has an ability to delegate. It would also be ideal to have someone familiar with the acquired company, its products, and culture. If, as often happens, two integration managers are selected (one from each company), it is important that one of the managers has the ultimate authority to make the final tough decisions.

One of the original companies in any merger or acquisition will be the leader in the new organization (often the smaller of the two) and it is dangerous to pretend that the two companies are equals. This is especially important when the deal is obviously an acquisition – unfortunately, there are many examples in which the acquirer has been improperly advised to refer to the deal as a “merger” in order to mollify the staff of the acquired company (for example, the acquisition of Bankers Trust by Deutsche Bank in 1999 when Deutsche Bank was perhaps overly sensitive about the cultural issues involved in being the first European bank to acquire a major US bank with a long and proud history).

The integration should also be facilitated by a number of task forces. The precise number will be dependent on the size and complexity (products and geographical locations) of the combined organization. These task forces will exist at different levels in the organization, although best practice would suggest the need for one overall “integration steering committee” to manage the whole process. They should also be managed by, and composed of, full-time employees, with external assistance where required. This process cannot be effectively outsourced, and companies that have tried to use consultants and others to manage the integration process have typically been less successful than those who recognize the importance of the tasks and therefore allocate adequate internal senior resources to the management and coordination of the following key tasks:

- Making key managerial and staff decisions.

- Developing a consistent strategy for each affected division.

- Aligning structures, systems, and processes.

- Identifying critical business risks.

- Determining corporate identity, brands, and imaging.

- Communicating, including the importance of tracking and using social media.

- Coordinating the temporary external advisors with the internal teams.

- Working with suppliers, especially where there are overlaps between suppliers of the two legacy companies.

- Resolving conflicts at all levels, internally and externally.

All of these areas are critical, whether obvious from the outset (such as cultural or product overlaps) or seemingly superficial but actually very important to some individuals (such as office location, branding, and company name). It is important to identify all of these issues early in the post-deal integration process or even before the acquisition closes.

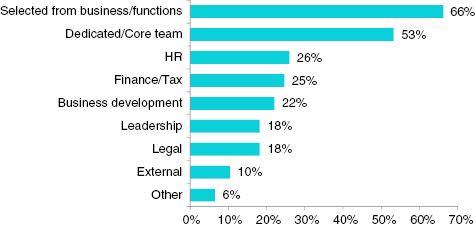

Additionally, all of the key departments in the company will need to be involved (see Figure 10.2), and early enough in the process to facilitate the integration. It is best if those who were involved with the planning of the deal can also play some role in the integration. As one manager of a Latin American financial advisory firm told us, “If people from the pre-closing team are seldom involved in and held accountable for the post-merger integration success, the post-closing team is left dealing with the implications of bad decisions made at the outset.”

Often the senior management team assumes that the back-office functions will be able to conduct the integration without adequate time to plan. As Gareth Creasey, Program Director, Mergers & Acquisitions at one high tech company told us, “IT [the Information Technology division] finds out about the deal in the morning of the announcement. The CIO [Chief Information Officer] is informed the night before.” And Tony Desai, Director, Strictly Acquisition, LLC said further of IT's involvement: “Traditionally IT's role was that of a deodorant. One felt its need only when it was absent.”

Engineer Successes

One way to maintain the client base, and even to grow it, while simultaneously motivating employees and suppliers to stay with the company, is through the engineering of successes. These successes then need to be communicated to the various stakeholders of the company.

The problem for two companies who have announced that they will merge is that people will be sceptical of the official announcements about why the deal makes sense and how it will be better for them, if they are clients, suppliers, or employees. It is therefore necessary to demonstrate success quickly. Yet, this is often very difficult, if not impossible, when the two companies haven't even combined yet! Thus the need to design a process whereby the companies can state publicly that it IS working. In one deal, when The Bank of New York merged with Mellon Financial, the CEOs of both banks knew that they would not be able to combine officially for a period of about six months, as they had numerous regulatory hurdles to pass before full integration would be possible. So how did they engineer an early success even before the deal closed? They set as a goal that they would “lose no clients.” This was a target that could be continually monitored even before the companies combined.

These stories about success can be used to demonstrate the power of the new organization and should be communicated as soon as possible after the deal is announced (and planned well before that time). When communicated properly, these will help to retain important clients, employees, and suppliers.

Advisors

Chapter 4 discussed the critical role of external advisors. Recall from that chapter that it is the advisors who are often the experts: they deal every day with mergers and acquisitions, whereas the merging companies may only do a significant deal once every few years.

Post-deal integration typically raises a new set of problems for the companies, and with it a different group of advisors. There will be a number of “outsiders” who play various roles in the post-deal integration, just as many of these individuals and organizations assisted the pre-merger process. In fact, some external advisors are needed for their skills: for example, certain human resource issues, such as pension fund planning and key manager appointments, legal advice regarding redundancies, outplacement services, and accounting issues such as the integration of the financial systems. These skills typically do not exist in most companies, as they only make the occasional acquisition, or there isn't sufficient excess capacity internally to deal with the extra demands of integration.

These advisors will need to be “controlled” and coordinated by the integration managers. Those managers will also need to keep an eye on “uncontrollable” outsiders (such as regulators, the press, financial analysts, and competitors) which will also need managing to the greatest degree possible. External expert advisors may be able to assist here, too.

Nurture Clients

With all the changes taking place within the company as it tries to integrate effectively, it is too easy to lose sight of the revenue side of the business, the focus on clients. While the company is worrying about who gets what job and what color the new logo will be, the outside world will not be so distracted: customers can be poached if they are not nurtured. Sharp competitors will use the uncertainty caused by a merger to their advantage while the attention of the new company is focused elsewhere. They will act quickly to poach clients (and targeting the best clients first) and staff (again starting with the high performing staff, as will be discussed below). Similarly, supplier relationships are at risk as well. A key challenge of the integration process is to make sure that business as usual continues while all the internal changes are taking place.

It is therefore important to encourage the sales force and relationship managers to be alert to signs of problems with their clients. This can be done through effective use of business intelligence. For example, Maersk Lines, in its 2005 acquisition of Royal P&O Nedlloyd to create the largest shipping carrier in the world, focused much of its post-deal integration effort on the retention of customers from both the Maersk Line side of the business and also the target's side. From their experience with earlier acquisitions, they had developed good post-deal communication processes with customers linked to a monitoring program to track revenues. This acquisition will be discussed further in the next chapter. Remember as well the discussion above (in “Engineering Success”) about IBM creating a “bump-free” client experience and BNY Mellon emphasizing focus on “lose no clients” whereby the latter ultimately claimed a 97% client retention rate as compared to a rate of close to 80% when two of their competitors merged a few years earlier.

Retain Key Employees

As with clients, it is critical for the ongoing business to retain key employees in both the acquiring and acquired companies. Each employee will be most concerned about “me.” If those concerns are not addressed, no other business will get done properly as managers and employees will be distracted: this will make it difficult to have effective integration and also will have an impact on the business. The intelligence function should help the acquirer to identify their key personnel, which is critical given that our own surveys found that even successful deals had a combined headcount after the first year that was 2.6% lower than the headcount of the two companies before they merged. It is notable that the combined headcount was only 1% less after the second year, which means that new employees were hired, but wouldn't it have been easier, better, and cheaper to have retained the employees during that first year?

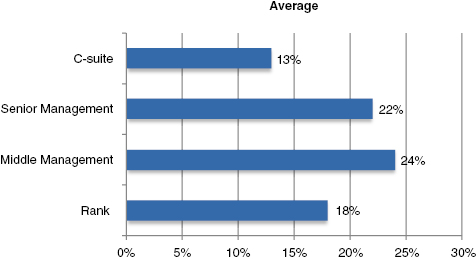

Human resource management issues during integration will include changing the board of directors, choosing the right people for the right positions at all levels in the organization, management and workforce redundancies, aligning performance evaluation and reward systems, developing employment packages and strategies to retain key people, and generally managing conflicting expectations of staff throughout the new company. All of this takes a high degree of coordination and sensitivity, and must be done immediately after the deal is announced. In the 2013 survey conducted by Mergermarket for TheStoryTellers, noted earlier, it was found that 48 days was the average time for employees to say that they were proud to work for the new company following an acquisition. One does not want to be losing the key employees during this period. That same survey found as well that up to a quarter of management (that the buyer wants to retain) end up leaving the newly combined companies, as shown in Figure 10.3.

A survey by Towers Watson released in early 2011 found that retention bonuses were the most effective tool that a company could use when it wanted to keep key employees following the announcement of a merger. Other tools, in order of effectiveness, were: providing equity grants in the new company, promotions to more senior roles, personal outreach by leaders and managers, participation in one or more integration task forces, and lateral moves either to new roles or different locations. Interesting, however, was the fact that only 23% of companies used the most effective technique of retention bonuses, and only 15% equity awards. The most commonly used tactic, by 40% of companies, was one of the least effective – moving someone to another lateral role. Another Towers Watson survey, in 2012, found that the company needs to identify the retention candidates early in the deal process, which means at or before the due diligence phase. Leaving this to the post-deal integration period may be too late as the top staff may already have left.

A critical task will be the early identification of these key employees. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, that group may not include the very senior management (CEO and CFO), who may be too wedded to the former organization. That same 2014 study by Cass Business School found that companies which retained operational staff boosted their success rate. Successful deals posted an average 63% retention rate for operational and business personnel, while for deals which ultimately failed, the retention rate was only 46% six months after closing.

An organization going through a merger or acquisition can be similar in many ways to an individual going through a divorce. It is a significant change and there are certain emotional responses that the organization or individual will pass through in becoming comfortable with the new situation. The psychological phases may range from denial and anger, through sadness and relief, to the end result: at least an acceptance of the situation and a feeling that “it's actually working out well.”

People-related issues typically represent much of the hidden post-deal integration cost to the new organization. Management consultant Scott Whitaker noted that in the first four to eight months following the closing of a deal, the productivity of staff is reduced by 50%. These and the other hidden costs noted earlier are often difficult to quantify. Organizations that anticipate these issues will be best positioned to deal with them effectively and minimize the negative financial impact they represent.

As with the stages of combination noted above, it is important to provide assistance to the organization and individuals to move them through these stages as rapidly as possible. Individuals within the acquirer and the target will behave differently. Often managers in the buyer will act with an air of superiority combined with a drive to dominate all the meetings and move as rapidly as possible to full integration. This may be at odds with the speed of integration needed to realize the benefits that the target brings to the new organization.

The target managers – those who have been chosen or who have decided to remain – may still be recovering from the shock of being taken over and will tend to be defensive about the strengths they bring (including the strengths of their systems and culture). They may have a sense of fatalism about them as they realize their lack of power to determine the outcome of meetings and may therefore consciously or unconsciously resist the changes.

During a merger, it is critical to monitor employees closely to determine how they feel and whether anything can be done by the organization to assist them in adapting to the new company. Certain warning signs that things may not be going as well as anticipated could include any of the following:

- Key employee departures to competitors.

- Increasing absenteeism and poor time-keeping.

- More customer complaints.

- Increasing union activity.

- Low level of employee participation at social events, training, or management courses.

- More legal claims.

- Deteriorating accident and safety record.

- Declining product quality.

- Increase in health insurance claims, especially stress-related.

All are evident from tracking employees, encouraging two-way communication, and the intelligence function. Often, independent organizations will be used to survey employees, but management itself needs to be trained and encouraged to watch for the warning signs as well to act to retain key employees.

Adjust, Plan, and Monitor

Adjustment, planning, and monitoring are necessary at all stages of the merger, and not least during the post-deal period. Managers should prepare for surprises – these will always occur in a situation as complex as merging two companies and their employees. Nothing should be cast in concrete: be willing to make changes, anticipate unexpected external (and internal) events, and manage them as best as possible. Surprises need not surprise: look for the warning signs. This is another area where business intelligence in the form of scenario planning could help. In planning, the managers of the new organization should not try for absolute certainty in the integration decisions, as it is too fluid a process and waiting is often worse than at least some action. Remember the quote from President Eisenhower (from Chapter 3): “I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

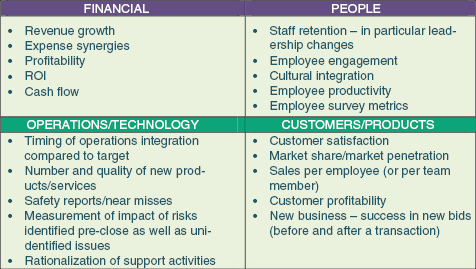

In terms of metrics, there is a wide range of factors that needs to be considered. Each deal is different, but generally these fall into the categories of financial, people, operations/technology, and customers/products, as outlined by Mercer, the management consulting firm, in Figure 10.4. Mercer also reported that 18% of companies tracked against these metrics for two to three years after the deal closed, and another 11% for up to five years. Not surprisingly, 78% of companies that tracked deals told them that using these metrics contributed to their deal success. Remember as well the discussion in Chapter 4 that noted a study which showed that integration milestones were more likely to be met when the corporate development department monitors the integration process.

Metrics not only provide management with the ability to track the progress of integration, but also a sense of control, raising red flags when something is not going to plan. Metrics can be used in other ways as well, being an effective tool to communicate demonstrable progress to employees, clients, and other stakeholders. They should be incorporated into the post-deal communications strategy discussed above.

As noted earlier, planning for the post-deal integration period should start at the beginning of the deal idea stage. This includes identification of who should fill key roles, their responsibilities, and mapping out what the future organization will look like. Business intelligence can be used to determine what changes will be necessary. The more that is done in advance of closing, the easier and faster the integration.

Integrate the Two Cultures

Employees embody and embrace their company's culture, and this culture will differ between the two organizations. The cultures will necessarily change during the integration, even in the acquirer. Cultural integration is paramount: ignoring the “soft” cultural issues of the two companies is a recipe for failure. (Recall the case study of Quaker Oats in Chapter 1, in which the entrepreneurial and quirky culture of Snapple could not be effectively integrated into the old-line, conservative culture of Quaker Oats, despite the fact that the management of Quaker Oats had intended that the acquisition would help to revitalize its company with new ideas.)

Clearly, attempting to integrate two cultures is incredibly difficult, even in situations where there are many apparent similarities between the two companies. When there is a merger rather than an acquisition this is perhaps even more difficult, as it may require a true and full integration and merging of cultures, rather than the adoption by one side (typically the smaller, target company) of the dominant acquirer's culture. If not done well, the culture clashes can destroy the speed and success of the deal, ultimately causing failure and even the divestiture of the acquired company. Therefore, culture can be a high risk factor for deal failure, and one which should not be ignored by management because it is a softer, less easily measured, factor. A survey conducted in 2013 at Cass Business School found that culture was considered by those doing deals to be the biggest contributor to deal success or failure.

Often, the cultural and business integration seeks to find the “best of both” from the two companies, jettisoning the lesser of the two for whichever cultural factor or business system or practice is being considered. The mistake is often to select the larger, stronger, or most experienced of the two, using that as the definition of “best.” A better approach would be to take the best elements of each and combine them to create a totally new culture that is structured to support best the developing strategy of the newly combined companies.

From the cultural side, it is important to make the social connections in terms of communication, identification of common core values, and recognizing the importance of “superficial” issues such as titles and company and division names. It is an issue not just for senior managers but all levels of the organization as both companies will have had unique cultures that may not instantly or naturally mesh. The expectations regarding culture must be articulated clearly by the leadership. As noted above, there is no merger of equals and this illusion should not be applied to the cultures either.

The management expert Peter Drucker posited “Five Commandments” for successful mergers, which mostly point to the importance of getting the culture right:

- Acquirer must contribute something to the acquired company.

- A common core of unity is required.

- Acquirer must respect the business of the acquired company.

- Within a year or so, the acquiring company must be able to provide top management to the acquired company.

- Within the first year of the merger, management in both companies should receive promotions across the entities.

Similarly, the acquisition will be a catalyst for other changes, such as management board responsibilities and risk management, and even the acquirer needs to be prepared to give up its identity.

Decide Quickly

When talking to almost anyone involved in a successful integration, the need for speed in decision-making is usually mentioned in the first sentence; not necessarily speed of integration, as that will depend on the type of deal. There may also be reasons to keep the newly acquired company separate, due to cultural or other business reasons. It is critically important, though, to make the key decisions very quickly, and to communicate these so that everyone understands what is required of them.

Uncertainty is the virus of successful post-deal integrations: it leads to customers, managers, and employees leaving, as noted above. It is not critical that every decision is made correctly; in fact, those same CEOs and senior managers who talk about the need for speed in M&A integrations have also said that they do not require 100% certainty.

The early decisions should be about the overall strategic direction that the new organization will take and which key managers at the top of the newly combined organization will be able to take that strategy forward. The decision making can then be delegated down through the organization.

Be careful of taking too much time to decide the emotive issues. There was one integration manager who told us that more time was spent at board level on determining the name of the newly combined company than all the human resources issues combined.

Speed in integration is also often helpful in achieving a successful merger of the two companies. This is especially true when the deal is between two companies of very different size, where the larger company is digesting the smaller one, which is anyway the largest share of deals as discussed earlier in this chapter. A PwC M&A integration survey in 2008 found that 82% of respondents said that they accomplished favorable cash flow results when integration was faster than normal. Nevertheless, some managers and employees will be uncomfortable with a rapid pace of change, and their concerns will need to be adequately addressed if the deal is to be successful.

Conclusion

In summary, a merger will bring a tremendous number of changes – many unanticipated – and it is critical to understand the importance of knowing how best to work through that change process during the integration. It would be a rare integration process that could fix a bad deal, however, so it is best that this follows a robust pre-closing process. As one CEO told us: “If the business case is wrong, the post-merger integration can hardly overcome the situation; reality is always more challenging than the business case, and you cannot expect the integration team to make miracles.”

The monitoring should allow for flexibility in implementation. It is especially important to include the base business in this: even those areas supposedly not affected by the merger. Early warning systems should alert the transition team and integration manager to any potential problems.