IRONWOOD

One of the world’s great engineering materials grows on trees.

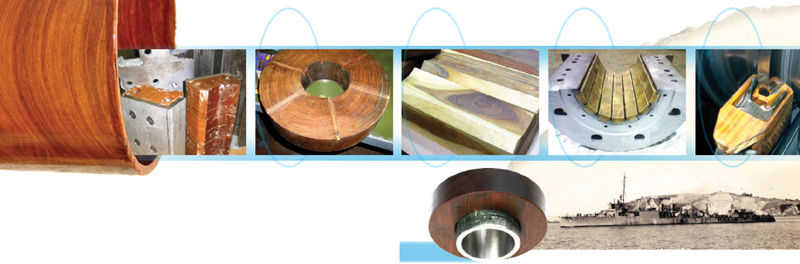

Lignum vitae stern tube bearings were used by the U.S. Navy.

Photos courtesy of Bob Shortridge

A simple shed up a gravel drive off a country road in rural Virginia is not where you’d expect to find the world’s largest stockpile of one of the great engineering materials. But find it there you will. The material is a tropical hardwood called lignum vitae (LIG-num VYE-tee). And the stockpile is the property and passion of a man named Bob Shortridge.

Shortridge is an expert timber framer — he’s the founder of Dreaming Creek timber frame homes — and for years, he used an old lignum vitae mallet to carve mortises and tenons in heavy oak beams. “You don’t want to be tap-tap-tapping on your chisel all day,” he said, and the lignum mallet had a heft that lighter plastic mallets couldn’t match. But the mallet was stolen, and he was unable to find a readymade replacement, or even the raw material to make one himself. He got curious. What made lignum vitae work so well? And why couldn’t he get any?

Lignum vitae is the wood of two closely related species, Guaiacum officinale and Guaiacum sanctum, native to the Caribbean islands and the arc of coast from the Yucatan through northern Brazil. They grow slowly and crookedly and don’t reach much more than 40 feet in height and 2 feet in diameter.

The name is Latin for “wood of life,” and comes from its adoption by late Renaissance Europeans as a kind of panacea. Filled with fragrant resins and oils, the heavenly scent was thought to be good for the earthly spirit and fleshly ailments. A 1540 pamphlet was entitled Of the Vvood Called Guaiacum, That Healeth the Frenche Pockes, and Also Helpeth the Goute in the Feete, the Stone, Palsey, Lepre, Dropsy, Fallynge Euyll, and Other Diseses.

But it was lignum vitae’s physical properties that brought it into widespread use. It’s one of the so-called ironwoods, 20 or so species (mostly tropical) renowned for the strength, durability, and density of their timber. Most ironwoods have specific gravities greater than 1: put them in water and they sink.

Lignum vitae is considered the toughest, strongest, and heaviest of them all. And its copious resins and oils render it virtually pestproof, almost immortal in both fresh and salt water, and naturally self-lubricating. And so it quickly became the high-strength stainless steel of the Age of Sail, used to make blocks and deadeyes for tensioning masts and sails, fids (oversized marlinspikes) for splicing ropes, and the pinions and bearings of the rudders. For two centuries, if it was vital to the working of a sailing ship and had to last, it was made of lignum vitae.

But amazingly, the wood continued to be vital long after sailing became obsolete. It turned out to be an ideal material for the thrust blocks and bearings needed to support propeller shafts: it can handle enormous axial loads, needs no oiling, and uses the water itself as coolant. Right through World War II, navy ships and even submarines relied on lignum bearings. The engineers of two of the largest icebreakers ever built, the U.S. Coast Guard’s 13,500-ton Polar Star and Polar Sea, mounted the ships’ triple screws on lignum. And the massive turbines of many older hydroelectric plants rest on it, as well.

In the second half of the 20th century, artificial bearings largely replaced lignum vitae. Shortridge built his stockpile because he wants to bring it back. He’s a lifelong, pragmatic conservationist. One reason he got into timber framing was to create a more valuable, sustainable market for mature white oak, which was being clear-cut just to make cheap, one-time-use pallets. And lignum is non-polluting, unlike metal bearings, which leak oil; natural and non-toxic, unlike the exotic materials used to make synthetic bearings; and renewable.

For years, Shortridge had to track down and buy up old stocks of lignum lumber, because Guaiacum had been virtually wiped out across its original range. But recently, he discovered an area in Central America where a healthy, self-sustaining population still grows. (He declines to specify where, worried that doing so would endanger them.) He has secured harvesting rights and implemented a forestry plan that takes only a fraction of the mature trees, and renders all harvested areas offlimits to further cutting for decades. His new venture, Lignum Vitae Bearings, is supplying brand new parts to shipbuilders, hydro plants, and other industries. Just like the originals, they’ll last 50, 60, even 70 years before needing replacement. It’s not a business that’ll ever rely on high-volume sales — but it’s one that’s built to last. ![]()

Tim Heffernan writes about heavy industry and the natural world. He lives in New York.