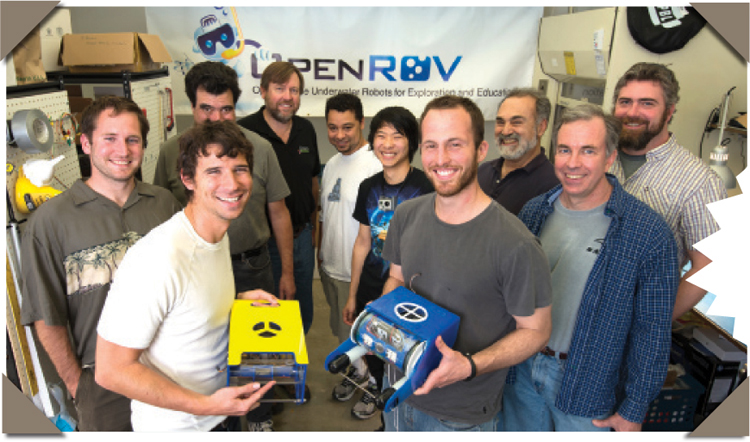

David Lang and Eric Stackpole, co-founders of the OpenROV underwater robot project.

Gregory Hayes

THE ACCIDENTAL maker

A pursuit of bandit gold leads to a different kind of treasure.

Nate Van Dyke

“Flashback ... 1800s. Northern California. Gold rush. Two Native American men rob a gold mining operation and make away with an estimated 100 pounds of gold. A sheriff’s posse is assembled to track them down.

After days of chase, they eventually catch the two men, but they no longer have the gold. The sheriff’s posse makes an offer: ‘Tell us where you hid the gold and we’ll spare your lives.’ The men explain that they hid the gold in the Hall City Cave. Despite the sheriff’s promise, both men are hung on the spot.

The posse returns to the area the men described and, sure enough, there’s a cave. They don’t find the gold, but toward the back of the cave they find a hole six feet in diameter and filled with water. The underwater cavern extends down farther than they can see, and they lack the tools or technology to explore further, so the sheriff’s posse gives up.”

Eric Stackpole, standing in the lobby of the Fisherman’s Wharf Hostel in San Francisco, took a deep breath and continued his story. He went on to recount numerous cave divers and treasure hunters who, having heard the Legend of the Hall City Cave, had tried and failed to reach the bottom, many of whom had stories of neardeath experiences.

By this time, my jaw was on the floor. This was the first time I had met Eric in person. The cave story was, quite literally, the beginning of the conversation. After Eric showed me an early prototype of the robot he was building to explore the cave, I knew I wanted to be involved — I had to be involved.

There was just one problem: I was completely useless. I had no making, design, or engineering skills to bring to the table. I had never even soldered before. But despite my lack of manual literacy, I convinced Eric to let me tag along. Having read about MakerBot and DIY Drones, I encouraged him to make the project open source, and told him I’d help document and share information. I knew how badly this type of adventure and excitement was missing from my office-bound life, and I was certain that others would feel the same.

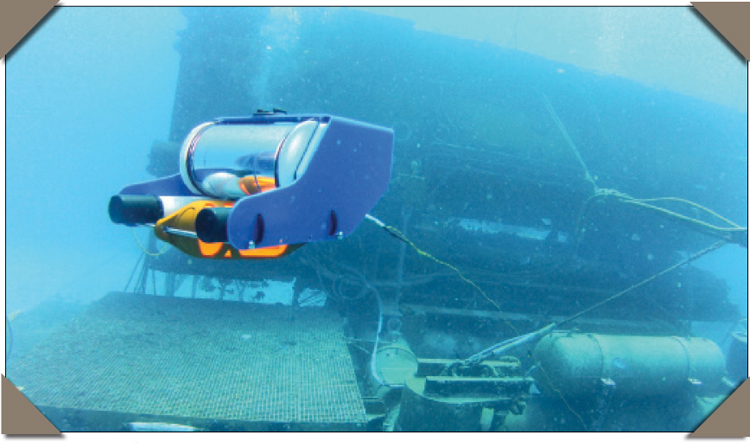

Testing OpenROV on NASA’s NEEMO-16 mission to the Aquarius Reef Base undersea laboratory in the Florida Keys.

Chris Gerty (undersea laboratory)

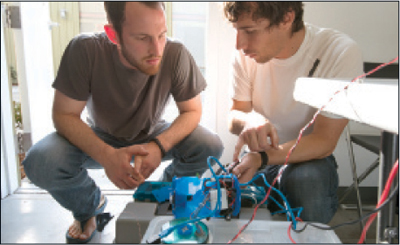

Shown at TechShop with his laser cutting class and with his welding instructor, Lang used the skills gained during his Zero To Maker experience to help develop these early prototypes of OpenROV.

Eric Stackpole (prototypes); Andrew Taylor

I never could have predicted where my desire to get involved would lead.

Zero to Maker

A few months after that inspiring meeting, Eric and I had created a website and forum for other DIY ocean explorers at OpenROV.com. I enjoyed it — I was learning a little bit here and there — but I was still a long way from considering myself a maker.

My moment, my push over the edge of the getting-involved cliff, came when I lost my day job working for a startup in Los Angeles. Although I knew the company was in a tough spot, I wasn’t prepared. The moment was sharp — a sudden realization that all I was qualified to do was sit in front of a computer screen. After meeting Eric and getting a taste for the adventure and possibility inherent to engineering and making, I knew I couldn’t just scramble back into the rat race.

I wanted the skills of an industrial designer but I didn’t have the time or money to go back to school. Instead, I decided to create my own DIY Industrial Design curriculum. I showed up at TechShop in San Francisco, told them my plan, and spent the next two months taking as many classes as I could — woodshop to welding, laser cutting to 3D scanning.

“I knew I wanted to be involved — I had to be involved.”

During the same time, OpenROV began to gain momentum. The forums grew from a back-and-forth discussion between Eric and me (mostly Eric explaining physics and underwater robotics to me) to a community of hundreds of people — amateur and professional ocean engineers alike. The idea of a low-cost, open-source underwater robot had clearly struck a nerve. With the help of this community, the robot design evolved, and we planned our trip to the Hall City Cave.

My skills steadily increased as I continued my “Zero to Maker” journey, which I documented for MAKE (blog.makezine.com/tag/zerotomaker). I was starting to move through the world differently: seeing problems as solvable and exciting, situations as malleable, curious about the origins and workings of everything.

The transformation didn’t take long — the span of just a few months — but it wasn’t always smooth. I found that the process was less about learning new tools than it was about adopting a “maker mentality.” There were subtle tricks I picked up through spending time with maker superheroes like Tim Anderson, writer of the “Heirloom Technology” column for MAKE, like learning “enough to be dangerous,” immediately trying to teach whatever I learned, and celebrating failure. Other lessons were big, obvious moments where I was clearly not one of the group. One of the most vivid lessons came the first time we water-tested our OpenROV.

Sunken Epiphany

Eric and I had finally come to a point in the process where the next logical step was to test the robot in the water. We set up our experiment in the backyard of my aunt’s house around the swimming pool, with my aunt curiously looking on. We decided Eric would be the videographer, leaving me to control the ROV. As Eric positioned the underwater camera, I tested the motors — they all ran perfectly, but were about to be put to the true test below the surface.

I lowered the robot into the water and walked back to the controls. Eric watched intently. I got back to the laptop and fired the forward thrusters — the two rear propellers which, when running in tandem, would push the robot forward. They worked! Well, they worked for a few minutes anyway, before one of the propellers stopped responding to the signals. We retrieved the robot and tried again, and it worked again briefly. Pretty soon, though, no matter what tricks or alterations we tried, we knew the ROV was underpowered. It sank to the bottom.

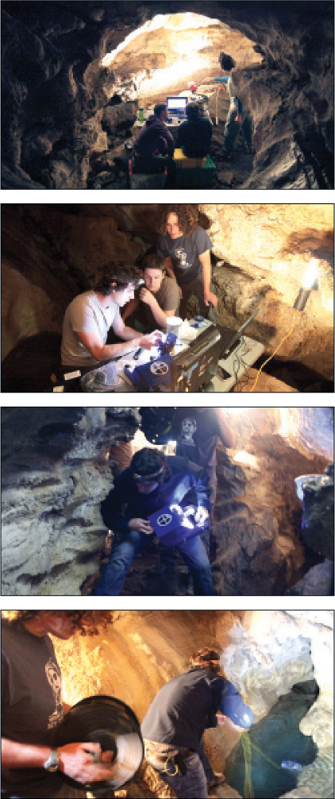

The OpenROV team inside the Hall City Cave, preparing to explore the underwater portion of the cave with an early OpenROV prototype.

Brian Lam, Zack Johnson (top)

At this moment — realizing all our previous work didn’t accomplish the goal — I saw the difference between Eric and myself. Again, I was useless. Nothing I could suggest would be of any help. While I was dwelling on the fact that it wasn’t working, Eric was already going through possible solutions. He was running calculations, trying different configurations, suggesting alternatives.

Gregory Hayes (far left); Gunther Kirsch

My perspective on the moment was different than Eric’s, in a way that couldn’t be attributed to our level of interest or initiative. I was, just like Eric, completely fascinated and intrigued by everything we were working on. I had, just like Eric, the willpower to try something new. Something else was different — something deeper than initiative and less formal than a master’s degree in engineering.

The difference was Eric’s incorrigible willingness to try things another way.

I’ve come to define that distinctly maker trait as the Persistent Tinkering Mentality (PTM), and I didn’t have it. Not naturally, anyway. But the robotsinking epiphany became a catalyst for change, and I’ve since developed a much stronger PTM muscle.

“The difference was Eric’s irrepressible willingness to try things another way.”

Community Is Golden

As my maker skills continued to develop, so did the OpenROV design, not because of my contributions, but because Eric and I had vastly improved the most important maker skill of all: sharing. The robot’s entire software stack was developed by the OpenROV community, which by the time we made the trip to the cave, had grown to nearly a thousand people. Nearly a dozen friends joined us for the adventure.

We didn’t find treasure in the cave, but it didn’t matter. We had built the robot we’d dreamed about and, more importantly, had a lot of fun doing it. We’ve discovered hundreds of new friends and collaborators interested in what we’re doing. Our open source team is now global, with the main software developers in Europe, and a distributed network of contributors and experimenters all over the world. Our development calls on Google+ frequently have participants from three continents.

The future of OpenROV is as much about the community as it is the robot. We want to continue to innovate and develop low-cost underwater robots — “cheaper and deeper”— but we also want to explore what’s possible with a distributed network of DIY ocean explorers. What might we find? How will we share data? What can we learn together? For me personally, the real treasure was never gold, but something far more precious. This maiden voyage of our little robot was a tremendous experience, but my journey started long before that day in the cave. My challenges were more fundamental than any technical design. I had gone from nonexistent engineering or design experience to making contributions to an award-winning underwater robot. A project that seemed intimidating and impossible to me only a year earlier had shaped me into a completely new person. I had flipped the switch from being a passive consumer of life to an engaged, creative participant in it. I had gone from Zero to Maker.

Maker Misconceptions

Before I dove into making, I barely knew which way to hold a hammer. I wasn’t sure I could ever fit in or learn the ropes. I had preconceived ideas about makers: who they were, how they worked, and how they learned. I imagined a long, lonely, and tedious study of engineering, tools, and science — skills that I had bypassed on the fast track to be more “marketable.”

My assumptions were completely off. These preconceptions turned out to be the toughest obstacle I would need to overcome. Once I recognized how unfounded they were, my own inner maker was able to come crawing out of his shell.

1. It’s not about DIY.

I quickly learned how makers really work: together. I was surprised that making was such a team sport. My first trip to Maker Faire left me with the impression makers were lone geniuses, toiling away in garages or workshops, putting countless hours into a project, repair, or invention and coming together once a year to show off their creations. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Makers are, above all, a connected and collaborative bunch. They meet online and share ideas on forums, blogs, and discussion groups. They give away their designs and collaborate on projects with people all over the world — the exact opposite of the competitive secrecy I had come to embrace in the corporate world.

Ahoy, future! David Lang, left, and Eric Stackpole point the way.

Gregory Hayes

Gregory Hayes

They’ve pooled resources to create fab labs and makerspaces — physical spaces that serve as hubs for sharing costs and maintenance of larger tools and equipment. It didn’t take me long to understand that little of anything is being done “yourself.” Making is not really about DIY, it’s about DIT, or Do It Together.

2. These aren’t my grandfather’s tools.

Before my immersion, I had a sentimental notion that DIY was about bringing back a bygone era — before hammers and nails were replaced with video games and iPads. I imagined DIYers to be torchbearers, keeping alive the methods and craftsmanship that were marginalized by the onslaught of screens and advertisements. I wanted making to help me connect with something I felt had been lost over the past few generations — a part of being a self-sufficient human that was missing from my life.

“Makers are, above all, a connected and collaborative bunch.”

In a way, makers are the guardians of this industrious self-reliance I had hoped for, but together they’re so much more. They understand and respect their place in history, in a long line of tool makers and tool users. While they do keep traditional knowledge alive, they’re also busy inventing and bringing new technologies into the world.

The new maker tools are byproducts of increasingly affordable computers, components, and sensors. Fueled by the rapid exchange of ideas on the internet, they’re empowering individuals and small groups with a slew of new personal fabrication tools. 3D printers, laser cutters, and other CNC machines (automated machine tools) are now affordable for a home workshop and capable of creating customizable, consumer-ready products.

A product that would’ve cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to prototype and produce 15 years ago can now be created with a downloadable file and access to one of the makerspaces that are popping up in cities all over the world.

The OpenROV flies past the Aquarius Undersea Laboratory, four miles off the coast of Key Largo. The dive was part of the NASA NEEMO 16 mission, extreme environment training for astronauts.

Chris Gerty

3. Only learn “enough to be dangerous.”

Learning to use these tools was shockingly easy. When I started, I predicted I would need a degree in industrial design or mechanical engineering before I could make anything useful or valuable. I never imagined I could come so far in such a short time. In only a few months, I was 3D printing, teaching others how to use the laser cutter, and designing basic parts in CAD (computer-aided design) programs. I started welding, working with sheet metal, and creating plastic molds. I was clearly not a master welder or microcontroller programmer, but I knew enough to get started.

Anything I didn’t know — how to use a machine, what material to use, how to assemble something — I could pick up on the fly. I learned skills as I needed them, depending on the specific problem facing me. And I was never alone. All the makers I met seemed to specialize in one area or another, and everyone was happy to teach what they knew. In fact, I discovered that everyone still had a lot to learn, but we were all able to leverage one another’s skills and knowledge.

Once I let go of my misconceptions, I was welcomed into a community of possibility.

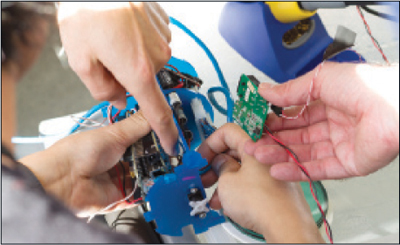

At the OpenROV HQ, members gather for one of the monthly build days.

Gregory Hayes

I realized I was part of something much larger: a maker movement. In exploring this new world, I saw another side of myself, a part that revels in the process of creating and sharing with others.

As it turned out, we never found any treasure in the bottom of the Hall City Cave. Instead, we discovered a community of global collaborators, which has been far more valuable and definitely more fun. ![]()

BIO

David Lang is a co-founder of OpenROV, an open source community of DIY ocean explorers. He is a contributing editor at MAKE and the author of Zero To Maker, a how-to guide for getting involved (and up-to-speed) with the maker movement. He is also a TED Fellow. Prior to underwater robots, David managed a sailing school in Berkeley. He currently lives on a sailboat in the San Francisco Bay.