8 The legal framework of employment

A manager with responsibilities for human resources cannot ignore the legal framework of employment. There is a great volume of employment law and it is both complex and subject to frequent change. This chapter can only outline the law sufficiently to alert managers to the circumstances in which they may need to seek expert advice. It must be understood that the broad rules set out here may be subject to qualifications which might modify their operation in particular situations.

8.1 The legal system in Britain

To understand employment law it is necessary to have some knowledge of the legal system. Strictly speaking, laws are enforceable only within the jurisdiction to which they apply and within the UK there are three distinct jurisdictions, namely, (a) England and Wales; (b) Scotland ((a) and (b) together make up Great Britain); and (c) Northern Ireland. However, as the three jurisdictions share one Parliament, and the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords is for most purposes the highest appeal court for each, there are few major regional differences. Moreover, the development of the European Union has already brought a high level of harmonisation of laws throughout the Member States.

Sources of law

Laws stem from two important sources: litigation and legislation.

Litigation: In former times this was the more important source of English law. Centuries ago judges decided disputes according to local custom; in time, through reporting of judgements, some customs became common to the whole country and provided the foundation of the ‘common law’ system whereby the decisions of the higher courts create precedents which are binding in future litigation. Today good reporting ensures that the majority of significant judicial decisions are published.

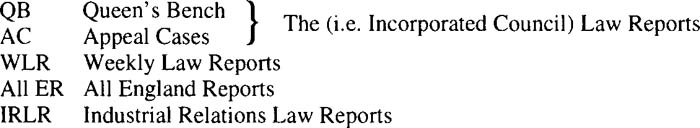

A number of cases are cited in this chapter so it may be helpful to explain the referencing system which lawyers employ to denote where a case can be found in a law library. For example, the citation Gascol Conversions Ltd v Mercer [1974] ICR 420 indicates that this case (which incidentally bears the names of those involved in the litigation) is reported at page 420 of Industrial Cases Reports for the year 1974. Other important modern series of reports are:

Managers may subscribe to IRLR: quality daily papers usually carry brief reports of the more important of the previous day’s hearings as part of their news service. The Times reports are available on the Internet.

The development of legal rules through decided cases has limitations since, on the one hand, it depends on the fortuitous occurrence of situations which provoke litigation and, on the other, the system of precedent can produce rules which cannot easily be adapted as society changes.

Legislation: Since the beginning of the twentieth century the UK Parliament has increasingly legislated to direct the development of the law although the foundations of modern employment law were laid in the nineteenth century. In the UK because legislation has developed pragmatically to deal piecemeal with defects in the law, there is no single Act of Parliament constituting a code in which all rules relating to employment are contained. Most of the legislation currently in force originated in the 1970s but such has been the pace of change that barely a year has passed without major amendments being made. The position has been somewhat simplified in the 1990s by two major consolidation statutes: the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 (hereafter TULR(C) Act) and the Employment Rights Act 1996 (hereafter ER Act). The first of these brings together trade union law, including individual worker rights in relation to trade union membership and activities, and the latter replaces the Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act 1978.

Other major statutes which will be considered in some detail here are

Equal Pay Act 1970 (as amended)

Health and Safety at Work Act 1974

Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (as amended)

Subordinate legislation: So complex has society become that Parliament has not for many years attempted to legislate in detail; the detail has been spelt out in regulations made subordinate to the framework legislation.

Codes of Practice: Statutes may also enable, or even direct that a Code of Practice be made to provide guidance as to a proper mode of conduct in given circumstances within the scope of the statute’s provisions. The Code of Practice is a regulatory device which enables legislation to be fleshed out without introducing the rigidity of subordinate legislation, for unlike statutes and regulations, compliance with Codes of Practice is not mandatory. Codes may be of evidential value in a court of law, and in reality it is very hard to justify why the relevant code has not been followed. There are a number of Codes of Practice relevant to employment law: a very important example is the Code of Practice on Disciplinary Practice and Procedures in Employment.

Europe: When the UK joined the European Community in 1973 it became immediately bound by the founding treaties, particularly the 1957 Treaty of Rome – cornerstone of the European Economic Community – (some Articles of this Treaty, such as Article 119 on equal pay, are very important to employment law) and by any laws made further to the Treaties.

The European Union (EU), since 1993, most frequently legislates by adopting Directives to further the purposes of the Treaties: a Directive is, as its name suggests, an instruction to the Member States. It requires them to implement its provisions, within a stated time. In the UK Directives are sometimes implemented in Acts of Parliament (e.g. the Sex Discrimination Act); sometimes by regulations made under an existing statute, e.g. the Framework Directive (89/391/EEC) to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work, was implemented in Great Britain by the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1992, which were made under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. It is also possible for regulations to be made under the European Communities Act 1972, an Act of the UK Parliament passed to facilitate the UK’s entry into the European Community. The troublesome Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 1981 were made in this way to implement the Acquired Rights Directive (77/187/EEC). The UK response to Directives is often to make separate provision for the various jurisdictions which make up the UK, e.g. the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 does not apply to Northern Ireland.

If experience proves that UK legislation has failed to capture the intention of the EC, further amending legislation may be necessary: thus the Equal Pay Act 1970 was amended by the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations 1983 to introduce the concept of work of equal value into the Act of 1970.

Interpretation: Words used in legislation often require interpretation: indeed, there is an Interpretation Act 1978, which interprets words frequently used in legislation, for example, ‘he’ used in a statute normally includes ‘she’ (a lawyer’s discriminatory practice employed in places in this chapter!). In spite of this Act much statutory interpretation is left to courts, and case law which develops in relation to an Act of Parliament can considerably influence the impact of the legislation; therefore the legal practitioner relies less on a Stationery Office copy of a statute than upon text books which incorporate subsequent judicial interpretations of that legislation. In recent years the interpretations of the European Court of Justice in litigation concerning other Member States have had an effect on the interpretation of UK laws.

Deregulation: In the 1990s the UK government has been committed to reducing the amount of detailed regulation, but it is proving difficult to reconcile this objective with the commitment of the EU to producing detailed rules in order to harmonise the law of the Member States.

Criminal and civil law

Rules of law fall into two main categories: criminal and civil.

Criminal law: This aims to regulate society, and imposes sanctions, such as fines and imprisonment, on those who do not observe the rules. Criminal cases are normally brought to court by the police (through the Crown Prosecution Service) or by a special enforcement agency such as the Health and Safety Executive’s inspectorate. Criminal law is enforced in England through the magistrates’ courts and the Crown Court. Minor criminal charges are tried summarily in magistrates’ courts; serious offences are tried upon indictment, before a jury, in a session of the Crown Court, but only after a preliminary enquiry has been conducted in a magistrates’ court to determine whether there is a case to answer. Appeal may lie from decisions of the Crown Court to the Court of Appeal, and thence to the House of Lords.

The criminal law plays a relatively unimportant role in employment matters, with the notable exception that breaches of occupational health and safety laws are usually criminal offences, but management will, no doubt, cooperate with the police should it appear that criminal offences, for example theft, have occurred at the workplace. Also, industrial disputes have a regrettable tendency to encourage violence; for example, picketing has often provoked police intervention with resultant criminal prosecutions. The rules invoked in such situations will normally be drawn from the general body of the law, rather than employment law.

Civil law: This is intended to give parties the opportunity to obtain redress from the person or organisation who has injured them. In England most civil disputes are determined in county courts, but cases which are very complex or involve a lot of money are tried at first instance (i.e. initially) in the High Court. Appeals go to the Court of Appeal and finally to the House of Lords. There are different courts in other parts of the UK.

European Court of Justice (ECJ): Where there appears to be a difference between UK and Community law the matter may be reviewed in the ECJ. The ECJ is empowered to hear references from national courts for interpretation of Community law (Article 177 of the Treaty of Rome and s.3(1) of the European Communities Act 1972): it is also concerned with actions alleging failures by Member States to fulfil the obligations of the Treaty of Rome (Article 170). The UK has been brought to account on several occasions, for example in Commission v United Kingdom (safeguarding of employees’ rights in the event of transfers of undertakings) [1994] ICR 664, the ECJ found the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations to be deficient because they did not provide for consultation with employees where there was no relevant recognised trade union. Consequently, UK law was changed by the Collective Redundancies and Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) (Amendment) Regulations 1995.

Even an industrial tribunal (see below) may refer a question to the ECJ for interpretation. However, the European Communities Act 1972 directs UK courts to interpret the laws before them in accordance with any relevant Community laws and so judges give a ‘purposive’ interpretation of UK statutes to give effect to EU law wherever possible (see Pickstone v Freemans PLC [1989] 3 WLR 265 – where the House of Lords granted a women’s equal pay claim even though there was a man employed on the same work).

The rights of the individual employee to apply to the court for interpretation of employment provisions are complex: they depend on the nature of the rule in dispute and whether the employee is in public or private employment. Article 119 (on equal pay) being unequivocal can be directly relied on by employees (see Marshall v Southampton & SW Hants AHA [1986] 2 WLR 780).

Industrial tribunals

Employees (and in some cases workers more generally) have, since the late 1960s, by statutes been granted rights (such as the right not to be unfairly dismissed) which are enforceable only through industrial tribunals. Such rights are additional to common law rights (such as those relating to wrongful dismissal) which were formerly, and remain even today, enforceable in county courts and the High Court. While these statutory rights are not themselves enforceable in common law courts, common law rules may influence the decision reached in cases concerning such rules. Tribunals are empowered by the Industrial Tribunals Extension of Jurisdiction (England and Wales) Order 1994 to hear most claims for common law damages which are outstanding on the termination of an employee’s contract of employment.

Appeals from an industrial tribunal lie on a matter of law to the Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) (a special court of High Court status); further appeal lies with the Court of Appeal and finally to the House of Lords. Since the higher appellate courts are common law courts they also tend, some believe wrongly, to infuse principles of common law into the statutory system and, unlike industrial tribunals, they (including the EAT) provide binding precedents on statutory interpretation.

Originally it was imagined that industrial tribunals would provide a swift and cheap resolution of employees’ complaints; so complainants are not entitled to legal aid. Experience has shown that issues can be complex and when cases are appealed it may be a long time before a dispute is finally resolved. The rules of operation of industrial tribunals are now largely contained in the Industrial Tribunals Act 1996. Industrial tribunals are likely to be renamed employment tribunals and alternative methods of dispute resolution may be introduced (Employment Rights (Dispute Resolution) Bill).

Advice, conciliation and arbitration

Legislation (currently the TULR(C) Act), has provided for an official Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) to promote the improvement of industrial relations, and in particular to encourage the extension of collective bargaining. ACAS is empowered to provide, free of charge, advice to employers, employers’ associations, workers and trade unions on any matters concerned with industrial relations or employment policies. It may also publish general advice on these matters. In addition, it may issue Codes of Practice containing practical guidance to promote the improvement of industrial relations. Its most significant code is that on disciplinary practice and procedures. It is also empowered to inquire into any question relating to industrial relations generally, or in any particular industry or undertaking and (with certain safeguards) publish its findings.

ACAS’s mission is to improve the performance and effectiveness of organisations by providing an independent and impartial service to prevent and resolve disputes. Thus ACAS’s statutory functions include the provision of assistance in the settlement of workplace disputes. An ACAS conciliation officer will offer assistance (merely to facilitate a settlement) where any complaint has been filed with an industrial tribunal.

Parties to an agreement may always include in that agreement a provision that in the event of dispute they will ask a particular person, or institution, to arbitrate: even if the original agreement did not make provision for use of arbitration, the parties may elect to go to arbitration when a dispute has actually arisen. Arbitration has not traditionally featured strongly in UK employment law, though it may be used to determine a dispute which has arisen out of a collective agreement. Where there is a strike or one is threatened, ACAS may, at the request of one or more of the parties to the dispute, and with the consent of all, refer the matter to the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC).

It is possible, in theory, for disputes between an individual employee and employer to be resolved by arbitration but this has not been customary in the UK, though there has been some support for such systems to be used instead of the present statutory procedures involving industrial tribunals. However, as the law currently stands, this could only be done if there was a special dismissal procedure (see ER Act s. 110), otherwise any arrangement for arbitration would be likely to fall foul of the rule prohibiting persons from bringing proceedings before an industrial tribunal (ER Act s.203).

Collective and individual employment law

Common law considered the employment relationship as essentially an individual arrangement between employer and employee, creating personal, and non-assignable rights and duties for the parties to it (Nokes v Doncaster Amalgamated Collieries Ltd [1940] AC 1014). Today the ability of the parties to negotiate contractual terms is somewhat restricted by statutory controls: for example, the very rule as to the personal nature of the relationship has been largely undermined by the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 1981, which are intended to protect the employee from suffering termination of contract when the employer transfers the business to another employer (Regulation 4A entitles the employee to refuse transfer but 4B intends that in the event of refusal the employee will be treated as having voluntarily terminated the contract).

The significance of personal relationships in employment is also likely to be reduced where a trade union negotiates employment terms for a class of employees with an employer or its representative association. Individual contracts of employment may then incorporate collectively bargained terms. Any study of employment law has therefore to consider both the contractual relationship between the employer and employee and the relationship between the employer and trade union(s).

A third aspect is the relationship between the trade union and its individual members but this is beyond the scope of this chapter.

8.2 Individual employment law

The contract of employment at common law

Contract has played an important part in the development of English common law and there are many contractual rules which are applicable regardless of the context in, or the purposes for which, a contract has been formed; but, in addition to this general law, a number of specific rules have developed to govern that particular kind of contract known as a contract of employment. From 1970 onwards the contract of employment has been increasingly governed by statute, but arguably, in the recent past, legislation has for a number of reasons been less relevant and the role of common law has again become more prominent.

Identifying the contract of employment

It is important at the outset to distinguish a contract of employment from other contractual relationships, including other kinds of contracts for the performance of work, because both common law and statutes have distinguished the employee, i.e. the worker who has a contract of employment, and given such workers and their employers rights and duties which are at the core of employment law, and which distinguish employment from other commercial arrangements, like those for the provision of services or the sale of goods.

An employer who requires the outside of a building to be painted might negotiate in one of two ways for the performance of this work. He might either indicate the work to be done and ask another to quote a price for the job or, alternatively, he might ask someone to work for a certain wage until the task was completed. In this example the law would probably hold a contract arising out of the first arrangement to be a ‘contract for services’ because the parties to the contract might be regarded as contracting as separate business enterprises, so that the worker would be an independent contractor: the second arrangement would most probably be a ‘contract of service’, that is to say the worker would be held to be an employee and the relationship formed would be a contract of employment. The position in the first example would be unambiguous if the person tendering for the work were an employer of labour, or a person who had a large capital investment in plant whose use would significantly contribute to the performance of the task. Difficulties might arise in both situations if the worker engaged had only labour to offer but wished to be treated as ‘self-employed’ with an organisation separate from that of the employer. In such circumstances the law, rather than the contracting parties, would determine the nature of the contract and would tend to classify the arrangement as a contract of service, weighing the intention of the parties as only one of a number of relevant factors.

No single perfect test has been devised by the courts for the identification of the distinction between the two types of contract, in spite of the many cases which have been heard. One of the major problems is identifying a test which might be applied for whatever reason the contract might be under scrutiny. The worker’s status is relevant not only to determine the rights and duties contained in the contract, but also to determine the extent of the employer’s liability to third parties for injuries caused to them by the worker. It also determines assessment for income tax, though in recent years for some marginal situations, regulations have set out arrangements for payment of income tax independently of consideration of the type of contract under which work was performed. The Inland Revenue may thus have taken away one of the incentives for claiming self-employment status.

The courts have always held that the more the employer is able to control the activities of the worker, the more likely it is that that worker is an employee. However, there are many circumstances in which, although it is inappropriate for an employer to exercise any real control over a worker, there is no dispute that the worker is so ‘integrated’ into the employer’s organisation as to be an employee (servant). The courts therefore regard the ‘control test’ as only one factor in determining whether the contract is one of employment. The matter was analysed thus by Mackenna, J. in Ready Mixed Concrete (South East) Ltd v Minister of Pensions and National Insurance [1968] 2 QB 497:

a contract of service exists if the following three conditions are fulfilled: (i) the servant agrees that in consideration of a wage or other remuneration he will provide his own work and skill in the performance of some service for his master (ii) he agrees, expressly or impliedly, that in the performance of that service he will be subject to the other’s control in a sufficient degree to make that other master (iii) the other provisions of the contract are consistent with its being a contract of service.

The contractual provisions will not be consistent with there being a contract of employment if the worker is taking the chance of making a profit and running the risk of making a loss out of the sale of labour rather than offering personal service for a wage which will be paid regularly whether or not there is profitable employment.

This chapter is concerned with the attributes of the contract of employment, since it remains the principal employment relationship. In particular, modern statutory regulation of employment, such as social security law and unfair dismissal law, is primarily concerned with the protection of the employee rather than the self-employed person.

Legally binding agreement

A contract of employment is (as Mackenna, J. reaffirmed) a legally binding agreement. It is created by agreement, and while it exists it imposes rights and duties on the parties to it. In due course it is terminated.

Formation of the contract of employment

No person (whether employer or worker) in the UK is under any legal obligation to enter into a contract of employment: in a free society there is neither a right nor a duty to work, and conversely there is neither a right nor a duty to employ labour; but parties who elect to make contracts enter into obligations that they will normally be bound by law to honour, incurring liability if they fail to do so. Thus if persons enter contracts which promise employment ‘starting 1st of next month’, but learn on or before that date that they are not required, they may sue for damages, even though they have not actually earned their pay by doing the work (Sarker v South Tees Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (1997), The Times 23 April). On the other hand, if a person performs a task without previously entering an agreement under which the other party promised to pay for the work, no claim for payment will be possible (Lampleigh v Braithwait [1616] 80 ER 155). It will be unlawful discrimination, if a person intending to contract, refuses to do so with a particular person on grounds of race, sex or on grounds of being, or not being, a trade union member.

There are certain situations in which, although the parties have made an agreement, they will not have entered into a legally binding contract:

1. There is no intention to create legal relations. Where parties are negotiating in a commercial environment the courts will presume an intention to make a contract unless they have expressly said that they are not so doing, or that they are not may be implied from their conduct. The rule is not significant in regard to the contract of employment but explains why there is no litigation between employer and trade union for enforcement of the collective bargain; the customary rule that the collective bargain is presumed not to be intended to be legally binding (see Ford v Amalgamated Union of Engineering and Foundry Workers [1969] 2QB 303) is now enacted in TULR(C) Act, s.179.

2. The parties lack the legal capacity to make a binding contract. Certain persons are not allowed to incur normal legal obligations, for example, persons under the age of 18 have only a limited contractual capacity and can only be bound by contracts of employment which are beneficial to them. In former days this rule was important. Today there is a greater reliance on statutory protection enforced in the criminal courts (e.g. while the UK is reluctant to implement some of the provisions of the Directive on the Protection of Young People at Work (94/33/EC) the health and safety provisions are implemented under the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1992). There are few constraints on capacity which are important in the employment contract today: for example, although it is doubtful whether the Crown may bind itself contractually, civil servants have the same right as other employees to bring a complaint against their employer if they are unfairly dismissed (ER Act, s. 191).

3. The agreement is tainted by illegality. The courts will not assist in the enforcement of an agreement which is tainted by illegality. It would be difficult to identify all the situations in which a contract of employment might become unenforceable because of some illegality associated with its formation or performance. It is only possible to give examples here. Contracts in restraint of trade, that is contracts which unreasonably restrict the freedom of the employee to sell his labour to another employer, are illegal: such restraints are more likely to be considered unreasonable if they are to continue after the termination of the contract. Similarly unenforceable are contracts to evade income tax by classifying part of wages as expenses (see Napier v National Business Agency Ltd [1951] 2 All ER 264). Normally the courts refuse to assist a party to enforce any of his contractual rights where the contract is tainted by illegality, but in employment contracts sometimes they will sever the illegal aspects and enforce the remainder.

4. There is no consideration. The courts will not enforce an agreement in which there are not mutual obligations; each party must have agreed to make payment for what the other party is promising. Nevertheless, the courts do not normally investigate the adequacy of the bargain so an employee will not usually be able to repudiate employment because the agreed wage is below the ‘going rate’ for the job, especially while the UK does not have statutory minimum wage rates.

5. Form of the contract. There is no requirement that a contract of employment be made in writing, but writing provides valuable evidence of what was agreed. The disadvantage is that such a document is itself constraining, for it is difficult to persuade a court that more was actually expressly agreed than is in the document. A court would not, for example, be sympathetic towards the argument that, while the document referred to a 30-hour week, it was verbally agreed that a further 10 hours a week overtime were to be worked as a contractual obligation (see Gascol Conversions Ltd v Mercer [1974] ICR 420). The importance of having on record what was intended is now recognised by the statutory requirement that the employee receive written particulars of employment. As a consequence of the statutory requirement the majority of employers now purport to give a full written contract.

Agreed terms of the contract

Terms may be incorporated into a contract in one of two ways: by express agreement and by implication.

Express terms: The common law allows the parties freedom to determine the terms on which they will form the contract, and the courts will not require them to observe terms which they have not expressly or impliedly incorporated into their contract, unless the matter is governed by statute. An agreement between employer and union as to the terms of a contract of employment will not become part of an individual’s contract of employment unless the collectively agreed terms have been expressly or impliedly so incorporated (see National Coal Board v Galley [1958] 1 WLR 16).

In the past, employment law contracts tended to be rather terse and the parties had a regrettable tendency not to make express provision for many of the situations which might reasonably be expected to arise. This problem is largely alleviated by statute, now so phrased as to comply with the Proof of an Employment Relationship Directive (91/533/EEC).

Implied terms: The courts are prepared to imply a term into a contract to give business efficacy to that contract, or because it is obvious to a bystander that it was the intention of the parties to include such a term. In addition, they will imply a term into an employment contract because it is usual for such a term to be implied in employment contracts generally, or because the term is one which it is customary to include in an employment contract with the particular employer or in the particular industry. A term which is completely contrary to what the parties have actually said, or may by their conduct be deemed to have intended, will never be implied. As a result of case law it has long been recognised that there are duties to be implied in a contract of employment on the part of both the employer and the employee.

The duties of an employer are:

1. To pay the agreed wages when they have been earned. If an employee is unable to work because of illness the employer will certainly be bound to make payments of sums due under social security legislation but there may also be a duty to provide the employee with contractual pay (but see Mears v Safecar Security Ltd [1982] IRLR 183. In the case of a salaried employee, there is an implied term that wages will be paid during illness until the contract is terminated (Orman v Saville Sportswear [1960] 1 WLR 1055).

2. To provide the opportunity to work if the wage depends on the provision of work (Turner v Goldsmith [1891] 1 QB 544); the usual view is that the employer is entitled to retain a worker on full pay without provision of work (Collier v Sunday Referee Publishing Co Ltd [1940] 2KB 647) although this was doubted by Lord Denning in Langston v Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers [1974] ICR 180.

3. To reimburse the employee for expenditure properly incurred by the employee in the course of employment.

4. To take reasonable care to provide the employee with a safe system of work.

In the absence of agreement there is no duty on an employer to provide an employee with a reference. An employer who does provide a reference must take care to give an accurate one, otherwise there may be liability to pay damages to the employee (if the reference is defamatory) or to either the recipient of the reference (Hedley Byrne & Co. v Heller & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465) or the employee (Spring v Guardian Assurance Co. [1994] 3 All ER 129) where the reference is incorrect due to negligence. There might also be liability to compensate the employee if reference is made to ‘spent’ criminal offences (see Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974).

The duties of an employee are:

1. to perform contractual duties personally: their performance may not be delegated;

2. to obey reasonable orders; but a single act of disobedience is unlikely to be serious enough to warrant dismissal (Laws v London Chronicle Ltd [1959] 1 WLR 698);

3. to account to the employer for money received for the employer (Reading v Att. G [1951] AC 507);

4. to indemnify the employer for loss caused by incompetent performance of contractual obligations, e.g. by negligence (Lister v Romford Ice & Cold Storage Ltd [1957] AC 555). As a result of a gentlemen’s agreement between insurance companies this duty is unlikely to be enforced (but see Janata Bank v Ahmed [1981] IRLR 457).

5. to respect the employer’s trade secrets.

Breach of an implied term may lead to an action in a common law court for damages for breach of contract; in practice it is more likely to be evidence in either wrongful or unfair dismissal proceedings to justify or dispute the termination of the contractual relationship.

Statement of particulars of employment

Sections 1-7 of the ER Act require the employer to give the employee a written statement of particulars of employment not later than two months after the beginning of employment, and, if the contractual arrangements are subsequently changed, a new statement must be provided within a space of a month of the change. In essence the statement must give:

1. the names of the employer and employee;

2. the date when the employment began;

3. the date on which the employee’s continuous employment began (taking into account any relevant employment with a previous employer);

4. the scale or rate of remuneration;

5. the intervals at which remuneration is paid;

6. any provisions relating to hours of work;

7. any provisions relating to:

(a) holidays;

(b) sickness;

(c) pensions;

8. the notice required to terminate the contract;

9. the title of the job;

10. (where relevant) the expected duration of the employment;

11. the place of work;

12. any relevant collective agreements;

13. (where relevant) information about employment outside the UK.

The statement is also required to include (except in small firms) a note specifying any disciplinary rules or referring to a document which specifies such rules. It must also identify a person to whom the employee can apply if dissatisfied with any disciplinary decision and a person to whom to apply for redress of any grievance, the manner in which any such application should be made, and what, if any, further steps are consequent upon that application.

These requirements encourage employers positively to address the matters set out above, though there is no need to make provision for every one of these matters. Unfortunately, while well-informed employers comply with the statute, there is no effective means of ensuring that all employers are aware of and meet their obligations. There is no penalty for failing to provide these particulars but an employee who has not received an appropriate statement may complain to an industrial tribunal (ER Act 1995 s.11; see also Mears v Safecar Security Ltd [1982] IRLR 183).

The Act does not affect the common law rule that a contract of employment may be created orally, and care should be taken to ensure that a document which is given with the intention of achieving a minimal compliance with the Act is not unintentionally elevated to the status of a written contract. An employer could give the statutory statement this status by giving it to an employee stating that it was that employee’s contract of employment (see Gascol Conversions Ltd v Mercer [1974] ICR 420).

Termination at common law

At common law a contract is usually terminated by performance; each party carries out the contractual obligations and the contractual relationship ends. It has always been exceptional for a contract of employment to be terminated by performance though it is possible to create employment of this description by employing a person on the agreement, preferably recorded in writing for clarification of statutory rights, that the contract is for a fixed term (see now ER Act ss.95 and 197) or for a specific task.

The great majority of employment contracts are made for an indefinite period and are, at common law, terminated by variation, notice, breach or frustration.

Variation: The parties may agree to alter the terms of the contract (thus terminating it) and make a new one to have immediate effect: this is a negotiation of no practical importance in employment since the law presumes the total employment period is one continuous contract (ER Act s.210). It used to be thought that if either of the parties did not agree to accept a contractual variation which the other sought to impose unilaterally, the contract would be terminated. Case law has indicated that it may be possible for the aggrieved party to resist the variation (see e.g. Rigby v Ferodo Ltd [1988] ICR 29) but this may not be of great assistance in saving the contract on its original terms, in the long run, since the other party could respond by giving notice to terminate it (see notice below and also unfair dismissal).

Notice: The contract will be terminated if either party gives notice of wishing to terminate and that notice duly expires; alternatively, the employment may sometimes be terminated forthwith by the employer giving wages in lieu of notice. It is now necessary to give at least the statutory period of notice (ER Act s.86). The employee who has been continuously employed for 1 month or more is required to give the employer 1 week’s notice. The employee’s entitlement varies in length in accordance with the period for which that employee has been continuously employed by that employer:

Employment of over 1 month and under 2 years = 1 week’s notice.

Employment of over 2 years and under 12 years = 1 week’s notice for every year of service.

Employment of over 12 years = at least 12 weeks’ notice.

Now that an employee has statutory rights in relation to redundancy and unfair dismissal, it is unusual for an employer to be able to terminate by notice the contract of an employee with two or more years’ continuous employment without incurring further liability.

Breach: The contract will be terminated if one of the parties fails to fulfil the contractual obligations and the other party demonstrably regards this repudiatory conduct as a termination of the contract (see London Transport Executive v Clarke [1981] ICR 355). If the wrongful conduct is sufficiently serious for the injured party to be released from contractual obligations that party has no need to give notice to terminate the contract (ER Act s.86(6)).

The courts will not issue an order (i.e. specific performance) requiring the parties to continue an employment contract when one of them has indicated the wish to sever the relationship, but occasionally an injunction will be granted to prevent an employer carrying out an intention to terminate the contract, particularly if the employee concerned has had long and satisfactory service with that employer (Hill v CA Parsons & Co Ltd [1972] Ch 305).

Frustration: In certain rare circumstances a contract will be deemed to have terminated by operation of law because an event has occurred, beyond the control of the parties, which makes its further performance impossible or futile, always providing that this event is not one expressly provided for in the contract. Occasionally contracts of employment have been deemed to have been frustrated by outbreak of war, more frequently because of a long incapacitating illness (see Condor v Barron Knights Ltd [1966] 1 WLR 87) suffered by, or a prison sentence (see Hare v Murphy Bros. Ltd [1974] ICR 603) served by, the employee. The occurrence of the frustrating event immediately releases both parties from further contractual obligations. If an employee suffered a serious incapacitating accident it would seem that the relationship would be severed from the moment of the accident, but in the case of prolonged illness or imprisonment, the courts have not identified the exact time at which the relationship has ended and have in the past been content to hold that the contract has ceased to exist by the time that the employee seeks to return to work. Nowadays there is reluctance to see a case put outside the rules of unfair dismissal by an employer establishing that the contractual relationship was ended by frustration rather than by dismissal and judges have expressed the view that, if the contract is to be fairly terminated, the employer ought to note what has happened by formally dismissing the employee (see London Transport Executive v Clarke (see above)). Since the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 s.6, placed a duty on employers to make reasonable adjustments to accommodate a disabled employee, it may be more difficult for an employer to claim that an employee’s accident or illness has frustrated the contract.

Common law rights and remedies

If loss is suffered because the contract of employment is either broken or wrongfully terminated, an action for damages will lie in either a county court or the High Court but since 1994 industrial tribunals have some jurisdiction to deal with common law issues (see above). A common law action for wrongful dismissal may be attractive to the manager with an exceptional contractual entitlement to notice; but for most employees, since dismissal with notice is lawful, and damages will be limited to the sum, if any, due to compensate for an inadequate period of notice, and loss of fringe benefits, the common law provides little satisfaction (see Addis v Gramophone Co [1909] AC 488). The Court of Appeal has held that where a contract provides for wages in lieu of notice, the employee is entitled to payment for the full notice period: there should be no deduction in respect of earnings in the notice period (Abrahams v Performing Rights Society Ltd [1995]).

The unsatisfactory common law led to statutory reforms in the 1960s and 1970s to give employees protection against redundancy and unfair dismissal. However, the adequacy of these statutory remedies is questionable: they are dependent on the employee concerned having 2 years’ continuous employment before dismissal, and they are of little satisfaction in times of depression when alternative employment is hard to find. For these reasons there has been something of a revival of the use of common law courts both as a means of establishing contractual rights (e.g. R v BBC, ex p Lavelle [1983] IRLR 404) and as a means of preventing or postponing dismissal (Hill v Parsons, see above).

8.3 Statutory protection

Since the nineteenth century, but increasingly after 1970, legislation has provided workers, particularly employees, with protection during the performance of their work and in relation to the termination of that employment. Some of these statutory provisions have already been identified (e.g. the right to receive particulars of employment) but in the following sections the most important of the remainder will be indicated.

Equality of opportunity

The common law rules of contract are based on the assumption that the contractual parties have equality of bargaining power; they therefore proved unhelpful to minority groups whose bargaining power was weak. Women and racial minorities are especially vulnerable and it has proved necessary to legislate to make it unlawful to discriminate against a person on sexual (Equal Pay Act 1970 and Sex Discrimination Acts 1975 and 1986) or racial grounds (Race Relations Act 1976). The legislation, which (Equal Pay Act apart) is not confined to employment issues, has the positive objective of achieving equal opportunities, and the sex discrimination legislation, while predominantly concerned with eliminating discrimination against women, also outlaws discrimination against men. The sex discrimination and equal pay statutes are intended to implement the EU requirements for equal opportunities.

In addition, a variety of provisions have addressed employment-related discrimination against persons on grounds of trade union membership and activities, or because of their other roles and activities at the workplace. In relation to trade union membership (or non-membership), it is unlawful to refuse employment (TULR(C) Act s. 137), or to take action short of dismissal (s.146), or to dismiss an employee (s.152). In the case of employees the statute expressly states that the discrimination must not be on account either of membership/non-membership or union-related activities. Similar protection against discrimination during employment, or by dismissal, are granted to safety and other employee representatives, employees refusing Sunday work and employee trustees of occupational pension schemes. Recently the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 has addressed disability on grounds of physical or mental impairment. It remains lawful to discriminate on grounds which are not expressly prohibited, notably on grounds of age, unless such discrimination in fact amounts to sex discrimination (e.g. Price v Civil Service Commission [1978] ICR 27; James v Eastleigh Borough Council [1990] 2 AC 751).

The nature of discrimination: Sexual or racial discrimination may be direct or indirect. Direct discrimination is treating a person less favourably than another on grounds of sex or race. Indirect discrimination occurs when a person applies to one person the same requirement or condition which he applied to another but:

(a) which is such that the proportion of women (persons of the racial group) who can comply with it is considerably smaller than the proportion of men (persons not of that racial group) who can comply with it; and

(b) which he cannot show to be justified irrespective of the sex (colour, race, nationality or ethnic or national origins) of the person to whom it is applied; and

(c) which is to (her) detriment because (she) cannot comply with it.

Mostly direct discrimination is easily recognised but surprisingly in James v Eastleigh (see page 139) it was found to be direct discrimination to charge a 60-year-old man to use a swimming pool, whereas a woman could enter free at this age: this was so even though the apparent discrimination was a reflection of the age at which the old age pension became available.

Indirect discrimination sometimes occurs through practices which are so deeply embedded in culture and tradition that their discriminatory character is hard to recognise. It might, for example, be indirect discrimination to offer employment or promotion opportunities only to persons with a record of continuous full-time employment if it were established that only white men could comply with this requirement (see Price v Civil Service Commission, page 139). Indirect discrimination may be exonerated if it is established that there is a justification, but the courts are not sympathetic to explanations related merely to matters of practice or convenience (see Steel v Union of Post Office Workers [1978] ICR 181).

Discrimination in employment: Legislation makes discrimination unlawful in a number of specific situations related to the formation and execution of the contract of employment. It is unlawful for an employer to discriminate in the arrangements made for the purpose of determining who should be offered employment. This very wide provision could cover placing and wording of advertisements, the contents of application forms, and the procedure of selecting for interview.

It is unlawful to discriminate in the terms on which employment is offered or by refusing or deliberately omitting to offer employment. It is also unlawful to discriminate in respect of access to opportunities for promotion, transfer or training, or to any other benefits, facilities or services, or by refusing, or deliberately omitting, to afford access to them. It is unlawful to discriminate by dismissing or subjecting a person to any other detriment.

Discrimination in the matters outlined may be lawful if sex or race, as the case may be, is a ‘genuine occupational qualification’. Each Act includes a list of circumstances in which exceptionally discrimination may be allowed, as, for example, where the job involves participation in a dramatic performance and a particular type of person is required for reasons of authenticity.

Harassment (including harassment on grounds of sexual orientation) may amount to unlawful sex discrimination but dress codes may be lawful if circumstances require them, provided comparable rules are imposed for both sexes. In the recent past dismissal in relation to childbirth has been contested under both UK and EU laws (see Webb v Emo Air Cargo (UK) Ltd [1994] IRLR 482) but this form of discrimination may occur less in future, given it is now unlawful to dismiss a person merely on grounds of pregnancy.

It is also unlawful to discriminate in relation to pay. The Equal Pay Act 1970 deals with inequality between the sexes, a broadly similar provision to be found in the Race Relations Act 1976. The 1970 Act had the broad objective that where men and women were doing the same work, they should receive equal pay, but the enactment of a statutory formula to achieve this objective proved difficult and the original Act was revised.

Under the present law the terms of a woman’s contract are deemed to include an ‘equality clause’ which relates to both pay and other contractual terms so that it is not, for example, lawful to require a woman to work longer hours for the same pay as her male colleagues receive. The equality clause applies:

(a) where the woman is employed on like work with a man in the same employment;

(b) where the woman is employed on work rated as equivalent with that of a man in the same employment; and

(c) where a woman is employed on work which, not being work in relation to which (a) or (b) applies is, in terms of the demands made on her (for instance, under such headings as effort, skill and decision), of equal value to that of a man in the same employment.

In spite of the restriction in (c), the House of Lords has allowed an equal value claim to be made even though there was a man employed on like work: in the view of the House, to have decided otherwise would have defeated the objectives of Article 119 of the Treaty of Rome (Pickstone v.Freemans PLC [1988] IRLR 357). Certainly, any other decision would have invited employers to suppress wage rates by ensuring that there was at least a minimal representation of both sexes on the payroll.

An employer may avoid the requirements of the equality clause by proving that a variation in pay is genuinely due to a material factor (gmf) which is not the difference of sex. It is controversial how far ‘market forces’ can be used in this context. In Rainey v Greater Glasgow Health Board [1987] AC 224 the House of Lords was prepared to allow this as a lawful explanation of the lower pay rate for women as compared to men. But in Enderby v Frenchay HA [1994] 1 All ER 495, the European Court held that the burden was on the employer to justify the lower pay of the women and did not accept that it was a sufficient justification that the rates were determined in collective bargaining. In Ratcliffe v N. Yorks CC [1995] IRLR 439, the House of Lords found for dinner ladies who had been dismissed and re-engaged at lower rates in order to enable their employer to tender competitively.

Matters of sex discrimination and equal pay are often difficult to distinguish but they are areas in which there has frequently been reference to the European law and in these circumstances it is especially important to identify the basis of the complaint, for if it can be based on Article 119 of the Treaty (equal pay), the claimant can rely on direct enforcement of the decision regardless of whether the employer is in the public or private sector (see Jenkins v Kingsgate [1981] ICR 715). Claims concerned with inequality in age of retirement (Marshall v Southampton & SW Hants AHA [1986] IRLR 140) and pensionable age (Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange [1990] ICR 616) have been found to be equal pay claims within Article 119.

Equal pay and sex discrimination claims are presented by way of complaint to an industrial tribunal. ‘Equal value’ claims are subject to a complex procedure, under which an independent expert is appointed to investigate the claim. Hearings therefore tend to be protracted, but interesting comparisons have been pursued (see e.g. Hayward v Cammell Laird Shipbuilders Ltd [1988] IRLR 257 – comparison between a female cook and male shipyard workers). The impact of the Act generally is limited in that there is no provision for class actions, so claims are made only for individual, rather than groups of, workers. However, where the provisions of a collective agreement stipulate different contractual terms for employees according to sex, either party to the agreement may refer it to the CAC which has powers to direct that the agreement may be suitably amended. The Equal Opportunities Commission has now introduced a Code of Practice guiding employers in the implementation of equal value.

Both the Race Relations and the Sex Discrimination Acts contain provisions making it unlawful for bodies other than the employer to discriminate; in particular it is made unlawful for a trade union to discriminate in relation to membership.

The Commissions: Under each principal Act there is established a Commission which is charged with working towards the elimination of discrimination; for this purpose it is empowered to investigate where discriminatory practices appear to exist and to serve a ‘non-discrimination notice’ on any person whom the Commission is satisfied is committing, or has committed, unlawful discrimination. The notice requires the person on whom it is served to refrain from the discrimination and may require positive action to rectify the situation. If the notice is not complied with, the Commission may apply to a county court for an injunction: breach of such a court order would be contempt of court and could result, in the last resort, in imprisonment. The Commissions have used their powers to issue Codes of Practice relevant to employment.

Enforcement: The major responsibility for ensuring that unlawful discrimination is subject to legal process rests with the individuals who have suffered discrimination. It is frequently difficult for a complainant to obtain the information on which to base a complaint so the legislation has authorised a form by which the aggrieved person may question the respondent’s reasons for acting as alleged. Not only will the answers thus received help to determine whether a complaint should be made, but the document may constitute evidence at the hearing of a complaint. The Commission may assist a claimant, when a case is complex or involves an important matter of principle.

Positive discrimination and quotas: UK law, like EU law (see Kalanke v Frei Hansestadt Bremen [1995]) does not generally favour positive discrimination and has little sympathy for quotas. It does not permit a person to refute an allegation of discrimination by demonstrating operation of a ‘quota system’, but the production of employment records which showed a reasonable distribution of men and women and of racial groups might be evidence of lack of intention to discriminate in a particular case. Such evidence might be valuable in cases of indirect discrimination. These records are also likely to be valuable aids to management monitoring performance and evaluating policies (see recommendations of Equal Opportunities Commission’s Code of Practice).

The Disability Discrimination Act 1995: This came into effect in January 1997, with the objective of protecting anyone with a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term effect (i.e. for at least twelve months or is terminal) on ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. The Act is by no means a mirror image of the sex and race discrimination legislation: it does not expressly address indirect discrimination but does allow justification of direct discrimination. It prohibits discrimination in recruitment, promotions, transfer, benefits, dismissal and ‘any other detriments’. Employment-related claims lie in industrial tribunals. The effectiveness of the Act depends on regulations and codes of practice now being introduced to spell out its framework provisions such as Guidance on matters to be taken into account in determining questions relating to the definition of disability and Code of Practice for the elimination of discrimination in the field of employment against disabled persons or persons who have had a disability. A National Disability Council will advise the government.

Other major statutory rights during employment

The 1970s saw the introduction of a statutory floor of rights for employees during the course of their employment. In the years since, sometimes as a result of EU Directives, these rights have been further developed and amended. It is only possible to refer to them briefly here.

Terms relating to wages: These terms are as follows:

1. Protection of wages. The Wages Act 1986 (now ER Act ss. 13–27) gave workers certain rights to complain to an industrial tribunal in respect of problems related to payment of wages. The employer’s power to make deductions from wages or require payments from workers is restricted. Broadly, the employer may make only deductions where these are required by statute (e.g. PAYE) or there is an actual agreement between employer and worker. There is also special protection for those in retail employment: deductions for cash shortages must not exceed 10 per cent of the gross wages payable when the deduction fails to be made, though the deficit may be carried forward to the following pay day, and when the employment ends there is no limit to the amount the employer may deduct or demand. However, the Act does not permit an employer to make a deduction for over-payment of wages: a dispute on this matter must go before a county court. These provisions have much increased the workload of tribunals even though, in Delaney v Staples [1992] 1 AC 687, the House of Lords held that payment in lieu of notice was damages not wages (payment during ‘garden leave’, i.e. suspension during notice, is wages!). This distinction may not be important now that tribunals have jurisdiction to hear claims for common law damages.

2. Itemised pay statement. The employer is required to supply at or before the time at which wages are paid, a written statement showing the gross amount of wages, the amount and purposes of deductions, the net amount of wages payable and where different parts are paid in different ways, the amount and method of payment of each part payment (ER Act s.8).

3. Guarantee payments. An employee who has been continuously employed for at least one month, but has no contractual right to receive full wages when laid off because there is no work, must be paid according to the provisions of the statute. A guarantee payment is not due where the absence of work is caused by a trade dispute involving any employee of the employer or associated employer. Nor will an employee who has refused suitable alternative work, or failed to comply with reasonable requirements imposed by the employer, be entitled to payment. The amounts payable are relatively small so it is unlikely that the employee will obtain normal wages (ER Act ss.28–35). These provisions are not relevant to salaried employees who are entitled to full pay, even though there is no work for them to do.

4. Suspension from work on medical grounds. An employee who has to be suspended from normal work by his employer by reason of a statutory provision (and there is no suitable alternative employment) may not be dismissed; and is entitled, while suspended, to be paid for up to 26 weeks. These provisions apply to a few situations where a harmful substance, such as lead, could cause illness: they do not apply if the employee is in fact ill, and therefore entitled to sickness payments (ER Act ss.64–65).

Time off from work: These terms are as follows:

1. Time off for trade union duties. An employee who is an official of an independent trade union recognised by the employer is entitled to take paid time off during his working hours for:

(a) negotiations with the employer related to those aspects of collective bargaining for which the trade union is recognised by the employer; or

(b) undergoing training relevant to these duties (TULR(C) Act s.168).

There is a Code of Practice concerning the amount of time an employee should be permitted to take off.

2. Time off for trade union activities. An employer must permit an employee who is a member of an appropriate trade union to take time off during working hours to take part in trade union activities (TULR(C) Act s.170).

3. Time off for public duties. An employee who performs certain specified public duties, such as being a justice of the peace, is entitled, subject to certain provisos, to take time off for the purpose of those duties (ER Act s.50).

4. Time off to look for work or training. An employee given notice of dismissal for redundancy is entitled to reasonable time off to look for new employment or make arrangements for training for future employment (ER Act s.52).

5. Time off for ante-natal care. A pregnant employee is entitled to time off for ante-natal care (ER Act s.55).

Pregnancy and childbirth: Rights in pregnancy and childbirth have been considerably strengthened following the EC’s Protection of Pregnant Workers Directive (92/85/EC), but the UK was not involved when the Parental Leave Directive was initially discussed by the other 14 Member States.

The ER Act provides that a woman may not be dismissed on grounds of pregnancy (s.99) and one who is suspended from employment on maternity grounds is entitled to remuneration (s.66). A woman absent from work on maternity leave is entitled to the terms and conditions of employment — except remuneration — which would have been applicable if she had not been absent (e.g. she maintains her seniority) (s.71). She is entitled to at least 14 weeks’ maternity leave (s.73), but she may not return to work until two weeks after the birth and, if necessary, leave will be extended to cover this. Maternity leave may begin as early as the 29th week of the pregnancy but will begin on the first day after the beginning of the 6th week before the expected week of childbirth (ewc) on which she is absent from work because of the pregnancy. Entitlement to leave depends on notification to the employer, not less than 21 days before the intended start of the leave, and the employer may request a medical certificate (ss.74/75). An employee who has 2 years’ continuous employment by the beginning of the 11th week before the expected week of childbirth, has the right to return to work after the end of her maternity leave and up to 29 weeks after the childbirth, provided that she informs her employer at the same time when she informs him of the intention to take maternity leave (s.79), and complies with the other statutory requirements as to re-affirming her intention after the birth of the child.

Pay entitlement during maternity leave depends partly on statutory provisions and partly on the contract. Regulations provide that a woman who has 26 weeks’ continuous service by the 15th week before the ewc, who has had average earnings above the threshold for payment of National Insurance contributions for the 8 weeks ending with the qualifying week and (unless not reasonably practicable) given 21 days’ notice that she intends to stop work because of pregnancy, is entitled to 18 weeks’ statutory maternity pay: 6 weeks at 90 per cent of normal earnings, 12 weeks at sick pay rate. Her contract may give her a further entitlement related to her salary.

Occupational health and safety

The law has two roles in respect of occupational health and safety: it provides compensation for victims of industrial accidents and diseases and it provides operational standards with the objective of eliminating from the working environment the hazards which may cause accidents and ill-health.

Compensation: An injured person (quite apart from claiming social security benefits) may bring an action for damages, claiming both for loss of income and for ‘non-pecuniary’ loss such as pain and suffering. This is equally true whether the accident occurs at the workplace or elsewhere, even in the victim’s home. However, persons who suffer injury while at work, or as a result of work activities, were in practice more likely to succeed in their claims than were other categories of litigants; today the organisation’s responsibility to members of the public is virtually the same as to its employees (Margereson and Hancock v JW Roberts Ltd [1996]), though historically the employer owed a special responsibility to employees, based on an implied term in their contract. The desirability of employers providing compensation for injuries to their employees, where the employer is legally responsible, is recognised by the Employers’ Liability (Compulsory Insurance) Act 1969: it requires the employer to be insured against liability for such accidents if they arise out of and in the course of the employee’s employment.

To succeed in a claim for damages the plaintiff (victim) must prove either that the defendant has committed the tort of negligence or that he has broken a statutory duty.

Negligence When claiming in negligence the plaintiff must prove that the defendant owed a duty of care; that this duty was broken by negligent conduct; and that this breach caused the injury.

The courts today take a liberal view as to the existence of duty situations and few claims for personal injury fail because the plaintiff cannot establish the defendant’s duty to take care. Thus the plaintiff’s decision as to who to sue is largely determined by considering which of a range of possible defendants is likely to be able to pay any damages awarded, and what evidence there is of negligent conduct causing the injury. For the employee, the employer is likely to be the most attractive defendant, both because of the insurance requirement and because litigation has spelt out that employers must provide their employees with a safe system of work, including safe plant and equipment, a safe working place and instruction and training. Where the employer is a small sub-contractor, the plaintiff may prefer to sue a more substantial organisation, such as a head contractor, in the justifiable belief that the courts expect a high standard of care from large organisations.

Breach of statutory duty Sometimes a plaintiff can identify a statutory duty imposed upon a person (usually an employer) for the protection of persons such as the plaintiff, and show that this duty has been broken and that its breach has caused the plaintiff to suffer the alleged injury. The rules governing such claims are complex, but these actions have become less usual with the development of the tort of negligence and because modern statutory provisions lend themselves less to this form of litigation than did the legislation which pre-dated the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974.

Vicarious liability An employer is liable (even if not personally at fault) for the injuries caused by the wrongful acts of his employees in the course of their employment. So if one employee injures another (or a member of the public) by negligent conduct, the victim may claim damages from the employer (see Mersey Docks & Harbour Board v Coggins & Griffiths (Liverpool) Ltd and McFarlane [1947] AC 1).

Prevention: It is recognised that it is better to avoid industrial accidents and work-related ill-health than to compensate for them; so statutory codes have established standards for the workplace and special inspectors are appointed with powers to enter premises to investigate whether these standards are being observed. These statutory duties are enforced in the criminal courts. There were by 1970 more than 30 statutes concerned with safety at the workplace, perhaps the best known of which was the Factories Act 1961; in addition there were more than 500 regulations.

The Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 was a reforming Act. It was an enabling, or framework Act with the objectives of securing the health, safety and welfare of all persons at work and of protecting the public against risk arising out of the activities of persons at work. This legislation has now been underpinned by a number of sets of Regulations, many of them to implement Directives adopted under Article 118A of the Treaty of Rome. It will be noted that the Act extends protection to workers generally rather than just to employees: there is often some room for dispute whether EC Directives which do not usually use the word ‘employee’ are looking beyond the narrow interpretation of the employment relationship.

The 1974 Act set up the Health and Safety Commission and gave it a general responsibility for occupational health and safety. The tasks of inspection and enforcement were entrusted to the Health and Safety Executive and the inspectorates were brought under the control of the Executive. Many offences became triable upon indictment, and, in addition, the inspectorate was given new powers of enforcement through improvement and prohibition notices.

Improvement notices are orders from inspectors requiring persons upon whom they are served to carry out specific tasks to comply with their statutory duties. A prohibition notice is an order that a certain activity shall cease, on the grounds that it involves a risk of personal injury. It is a criminal offence to fail to comply with an order but the validity of the order may be disputed in an industrial tribunal.

General duties: The general duties contained in the 1974 Act (ss.2–9) aim to establish safe systems of work, and for this purpose they identify, and impose duties upon, those involved in the work activity. They are very broad but are of a high standard; for the most part they impose absolute liability for unsafe situations unless the accused can prove that it was not reasonably practicable to do more to achieve safety (e.g. R v British Steel PLC [1995] 1 WLR 1356).

Regulations may be made to create specific standards in respect of specific situations but although important regulations have been made, many incorporating EU standards (e.g. Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 1994), it seems unlikely that the general duties will ever be fully discharged by observing all the relevant regulations, since they encompass the total operational system.

It is fundamental to compliance with the 1974 Act that safety be seen as a matter of safe systems and related to the proper management of people. The principal responsibility for safety at the workplace falls upon employers and the Act requires them to do all that is reasonably practicable to ensure the health, safety and welfare at work of all their employees (s.2) and of other workers and the general public (s.3 e.g. R v Board of Trustees of the Science Museum [1993] 1 WLR 1171). The Act also places general duties on controllers of premises (s.4, see Mailer v Austin Rover Group PLC [1989] 2 All ER 1087) and those who supply articles and substances for use by people at work (s.6).

Section 7 imposes a duty upon employees while at work to take reasonable care for their own health and safety and that of other persons who may be affected by their acts or omissions at work and to cooperate with their employer and other persons to enable them to discharge their statutory obligations in respect of health and safety. EC Directives (reflected in British regulations) give some content to this duty, e.g. the Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992, regulation 5 requires ‘Each employee while at work shall make full and proper use of any system of work provided for his use by his employer’.

Supplementary to, and in explanation of, the general duty imposed on the employer in s.2(1) of the Act, s.2(2) requires:

(a) the provision and maintenance of plant and systems of work that are, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe and without risks to health;

(b) arrangements for ensuring, so far as is reasonably practicable, safety and absence of risks to health in connection with the use, handling, storage and transport of articles and substances;

(c) the provision of such information, instruction, training and supervision as is necessary to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety at work of his employees;

(d) so far as is reasonably practicable as regards any place of work under the employer’s control, the maintenance of it in a condition that is safe and without risks to health and the provision and maintenance of means of access to and egress from it that are safe and without such risks;

(e) the provision and maintenance of a working environment for his employees that is, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe, without risks to health, and adequate as regards facilities and arrangements for their welfare at work.

As part of his duty, the employer is also required to provide a written statement of his safety policy, and the organisation and arrangements for the time being in force for carrying out that policy and to bring this statement and any revision of it to the notice of all his employees. The arrangements which are set out should relate to the findings of the risk assessment which the employer is now required to make under the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1992.

Both the Act itself and regulations to comply with EC Directives (e.g. the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations and the Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations 1992) stress the need to provide instruction and training of workers. A relatively early decision of the Court of Appeal held that s.2(2)(c) obliged employers to provide information to sub-contractors’ men so that they did not endanger their own employees, and s.3(l) required them to provide information to the visiting workers for their own safety (R v Swan Hunter Shipbuilders and Telemeter Installations Ltd [1981] ICR 831). Subsequent cases have stressed the responsibility of employers to control the work of contractors and their employees (e.g. R v Associated Octel Ltd [1994] IRLR 540).

EC Directives require worker involvement in safety matters. The Safety Representatives and Safety Committees Regulations 1977 provide for recognised trade unions to appoint safety representatives. These regulations set out the functions of such representatives and the ways in which the employer is required to cooperate with them. Their principal functions are to carry out regular inspections of the workplace, to consult with the employer, to represent their constituents, to inspect documents and to receive information both from the employer and the inspectorate. They are also entitled to investigate accidents and must be consulted where changes are to be introduced at the workplace. Two safety representatives may require that the employer set up a safety committee, but there are no regulations as to the constitution and functions of such a committee. The regulations are not mandatory but represent a set of rights with which the employer with a recognised trade union may be required by the union to comply, in default of any alternative negotiated arrangements. Further regulations have now given slightly less generous rights to employees in workplaces where there is no recognised trade union.

The general duties may not be used in civil actions for compensation and they are enforceable in the criminal courts only by the inspectorate. Employers, the performance of whose duties to provide safe systems will often depend on the conduct of others, will need to rely on contractual arrangements to ensure that safety is maintained by these other people: under the contract of employment the employee whose conduct is unsafe may be disciplined; commercial contracts with other organisations may give the employer rights to monitor the conduct of these contractors and their workers; and purchase contracts may relate to the safety of the products to be supplied.

8.4 Statutory protection at dismissal

Unfair dismissal

Statutory provisions (now ER Act ss.94–135) give many employees the right not to be unfairly dismissed; the principal exceptions are most employees who have not the qualifying 2 years’ employment, and those who, at the time of dismissal are over retirement age.

There are no moral connotations in the term ‘unfair dismissal’; it has a statutory meaning and qualified employees are entitled to the statutory remedies even though their cases are without merit, but the complainant without merit may be denied compensation (see Devis & Sons Ltd v Atkins [1977] AC 931).

The employee who considers that (s)he has been unfairly dismissed may present a complaint to an industrial tribunal within three months of the effective date of termination of the employment, that is within three months of the last day on which the employment relationship subsisted (e.g. when working out notice, the date on which the notice to terminate expires). The general rules concerning effective date of termination might lead to hard cases (see Dixon v Stenor Ltd [1973] ICR 157), as for example where an employee is required to leave immediately and so reduce the qualifying period of service — in such cases employees are treated for the purpose of service as if they had worked out their notice.

The burden is on the employee to satisfy the tribunal that there has been dismissal, the burden then shifts to the employer to establish that the dismissal was for one of the reasons permitted by the statute. The statute provides (s.95(1)) that an employee shall be treated as dismissed if, but only if: