13 International human resource management

13.1 Importance of international HRM

Business is increasingly being transacted across national boundaries, within a highly competitive global context. Market place competitiveness — on price/cost/value/quality/innovation — is essential for business survival and, in the long term, most companies need to aim for growth, whether in domestic or foreign markets, to survive, otherwise stronger global competitors will take over their traditional domestic markets. In countries such as the UK, domestic markets for certain goods are saturated, so companies need to look overseas for growth opportunities.

The rate of ‘internationalisation’ of business will increase, not decrease, so an appreciation of aspects of business internationalisation will become ever more important for a manager. Business is carried out by and through people, whether customers, suppliers or employees, so those without some appreciation of managing people in an international context start with a career handicap. Even within national boundaries, the challenge of effectively managing a multicultural workforce is exercising many organisations.

What is international HRM?

International HRM is neither copying people management practices from other countries, as cultural differences inhibit effective transfer, nor learning about the cultures of every other country and modifying behaviour accordingly, as this is too time-consuming and more than slight behaviour adaptation is hard.1 What characterises international HRM is the interaction between the human resource functions, countries and types of employees:2 parent country nationals (PCNs), local or host country nationals (HCNs), and nationals from neither the parent nor host country but from a third country (TCNs).3 This creates greater complexity than is encountered when managing people within one country, plus the need for cross-cultural sensitivity.

What specifically comprises the human resource function will vary over time, between companies and countries, as will the identity of whoever — HRM specialist or line manager — executes these functions. International HRM is a fluid dynamic entity,4 changing whenever pressures in the organisation’s internal or external environment result in alterations to the business.5

As HRM is dynamic and context-specific, international HRM is not one theory, system or prescriptive approach to managing people, which can be applied globally. Each country and industry will have its own characteristics and thus its own HRM style. However, as some of the external environmental pressures, such as political systems, laws, economy, will influence all organisations within one country, there will be characteristics sufficiently in common to suggest national characteristics influencing HRM in that country, which can be used as guidelines by the non-national considering business there.

The areas of HRM practice which change significantly or require attention when undertaken internationally are, according to Torrington:6

• cosmopolitans (employing people who spend part of their time in another country);

• culture;

• compensation;

• communication;

• consultancy;

• competence (of people to work across cultural and national boundaries);

• coordination (between the parts of the organisation).

Whatever else international HRM is or is not, it also has relevance for the manager of a multicultural workforce7 operating within one country, as it is essentially about ‘managing people’, not necessarily employees, from culturally divergent backgrounds and it includes developing the processes, mechanisms and links needed to do so effectively.

Variables influencing international HRM

Variables internal to the company: the organisation can choose its policies and practices, structure, and staffing approaches. Although influenced by the external environment at strategic and operational level, these are largely within organisational control.

Variables external to the company: the political, economic, sociological, technological context of the country in which the company is operating. Traditionally, these are seen from an organisational perspective as uncontrollable variables with a one-way influence on internal variables and business strategy, rather than vice versa. Over time, however, the aggregation effect of similar business strategies or HRM practices across several organisations operating in the same external environment can influence the external variables. For example, the HR practices of several companies can influence the attitude of people to what is perceived as a ‘good’ employer.

Competitive position: the business strategy, deriving from the organisation’s competitive position, governs the nature of international HRM initiatives to some extent. If competition is largely on price, HRM initiatives which increase cost without adding positive value will be inappropriate.

A multinational enterprise (MNE) has to consider specific socio-economic, political, technical, and competitive variables and internal organisational variables in each country in which it operates. This, plus managing the ‘links’ between each country and an ‘alien status’ make international HRM and the role of its specialist HR more difficult.

Managing many variables and complexity is easier, and change speedier, if HR activities are decentralised to the units in question. This raises the issue of what to devolve. The approach taken should, in theory, match the structure of the business, which should reflect the overall business strategy; but in practice decisions are not so clear-cut. What if the organisation has many different types of business units abroad — small sales office, large and small manufacturing units, R&D facility, regional marketing centre, perhaps a couple of joint venture companies? The same approach to what is devolved may not be appropriate for all parts of the business.

Devolving all selection and promotion endangers availability of sufficiently broad-based and relevantly experienced senior staff for the future, which is why management development at middle/senior management level is seen by many organisations as too important to be left to national units. Apart from a holding company structure, the greater the decentralisation, the greater the need for integrative mechanisms, and management development can be a crucial integrating mechanism for a MNE operating globally.8

Philips Sound and Vision HRM is highly devolved but they pay great attention to international management development and integrative mechanisms:

• international and cross-functional secondments are arranged, e.g., a marketeer from the USA might be assigned to the head office HRM department in the Netherlands;

• meetings for staff from disparate locations and functions are arranged to exchange ideas and disseminate effective practices;

• business school graduates from a range of countries are taken on placement into the head office HRM department.

To avoid becoming inward-looking, Philips’ main board is not just staffed by Dutch nationals.

Convergence or divergence in international HRM practices?

The Price Waterhouse Cranfield Project9 studies, started in 1990, to assess the impact over time of the Single European Market on HRM and the degree to which a strategic coherent approach10 was being used (see Figure 13.1) found:

Figure 13.1 The integration/devolvement matrix: models of HRM in ten European countries

Source: Brewster, Larsen, Human resource management in Europe

• HRM issues are similar across Europe but they are handled differently;11

• distinct patterns of HRM amongst Nordic, Central European and Latin countries (this had been suggested by Hofstede’s 1980 national cultural values study12), but France did not fit easily into any of the three models;13

• common practices in terms of appraisal, development and job evaluation language;14

• increased written and verbal employee communications;

• increased usage of atypical work, part-time work and fixed-term contracts;

• the number of HR functional heads at board level varied considerably between countries but their involvement in business strategy was considerably lower than the number with board seats;15

• of those companies which had written HR strategies, only a half to 75 per cent turned these into action plans;16

• differences in the role of the HRM specialist in terms of involvement in organisational policy making and devolvement of HR practices to the line (see Figure 13.1);17

• devolvement tended to be of recruitment, selection and training, but not industrial relations, to line managers;18

• training is a key area of concern for a majority of European HRM departments;19

• strengths in national level centralised pay bargaining — except in the UK and France where it had decreased.20

The IBM/Towers Perrin Worldwide Study of HRM practices for achieving competitive advantage21 assessed the relative importance of various HR approaches and practices at the time of the survey and as perceived by the end of the century. The perceived future importance of the 38 HR practices surveyed, in achieving competitive advantage, was greater than at the time of the survey.22

These studies indicate the emergence of five groupings of countries, in terms of their approach to managing their human resources:

• the UK, Australia, the USA and Canada; with Germany and Italy moving towards this Anglo-Saxon HRM approach;

• France alone;

• Korea alone;

• Brazil, Mexico and Argentina;

• Japan.

13.2 Staffing the international organisation

Management and staffing approaches

Four broad approaches to managing and staffing foreign subsidiaries and senior HQ posts of an international organisation can be discerned:23

1. Ethnocentric: parent company nationals (PCNs) manage subsidiaries and staff senior HQ jobs; strategic decisions are made at headquarters.

2. Polycentric: subsidiaries have significant autonomy and are managed by host country nationals (HCNs) but PCNs fill senior headquarters jobs.

3. Regiocentric: HCNs and third country nationals (TCNs) from other countries within a geographic region are moved to senior posts within the region; significant regional decision-making autonomy.

4. Geocentric: a global strategy is established at headquarters; subsidiaries are managed and senior headquarters jobs are filled, regardless of nationality, by whoever has the requisite skills: PCNs, HCNs, TCNs.

The approach used must be consonant with overall business strategy and will depend on the nature of the business, its structure and resources, including the experience and skills of senior decision makers. The MNE may use different approaches in different parts of the world or in different product/service divisions.

Staff working outside their home country

An organisation needs to be clear conceptually about what it perceives to be the difference between the various categories of staff working internationally as this will impinge on the employment package offered. Torrington24 (1994) sees staff who work outside their home country as falling into five general categories, each of which has distinctive HRM and acculturation needs:

1. The ‘mobile worker’, who is not tied to one country or company but moves around as job opportunities present themselves.

2. The ‘occasional parachutist’, who makes occasional brief troubleshooting/meeting attending/subsidiary inspection visits to foreign parts.

3. The ‘engineer’, who, home country-based, makes forays, usually unaccompanied by family and often to remote inhospitable locations, of 2 weeks to 3 months abroad.

4. The ‘international manager’ who, probably multilingual and cross-culturally aware, makes frequent overseas short visits abroad liaising, selling, researching business opportunities, dealing with company and government representatives, without any involvement in the internal management structures of the organisations whose representatives he meets.

5. The ‘expatriate’ or ‘corporate transferee’, who has family-accompanied or unaccompanied job postings of 2 to 3 years in a foreign business unit before returning to a job in the home country.

It costs about three times as much to use an expatriate as to hire an HCN,25 so the organisation should carefully consider if and why expatriation is needed. Expatriate failure — the premature return of the expatriate, or sub-optimal performance in the foreign posting — is expensive; the direct costs of return and replacement may be exceeded by indirect costs: business contacts who have lost confidence in the organisation,26 lower morale amongst staff remaining in the subsidiary,27 and the returner’s decreased confidence which may affect performance on return.28 Particular attention should be paid to: selection and preparation for expatriation, support whilst away, and repatriation.

Selection for expatriation should be based upon: job factors, ability to relate to the other culture, motivation to expatriate, family situation and language skills.29 Managerial or technical skill is not an indicator of cultural adaptation skill.30 Lack of technical skill is rarely a cause of expatriate failure31 in USA and European MNEs, but inability to adapt to the new culture is, so emphasis should be placed in selection on identifying coping skills and a positive cross-cultural attitude, bearing in mind that a positive attitude is not necessarily reflected in behaviour.32

Motivation of both the employee and the family to expatriate — or to sustain an unaccompanied posting – is crucial; spouse adaptation affects the employee’s adaptation and hence assignment success.33 Inability of spouse34 or the family35 to adapt are the most common reasons for expatriate failure amongst USA and European MNEs, although amongst Japanese MNEs it is the employee’s failure to cope with larger foreign responsibilities.36

To minimise ‘culture shock’, before final appointments are made, a ‘taster’ visit to the proposed location helps mould realistic expectations of what living there will entail. Preparation for expatriation should include the spouse and children and, bearing in mind the problems of adjusting to international assignments which European managers cited most frequently: relationships and value differences with locals, work overload, the way business was done locally, language, and HCNs lacking appropriate skills,37 it should cover: cross-cultural issues specific to the new environment, advice, help and support on practical matters, and language training.

When in post, expatriates need time to adjust to the local environment; up to six months is suggested,38 so performance evaluations should allow for this. Coordinated local support facilities, including monitoring and meeting training and development needs, and the facilitation of a new social network, for the family too, both help to reduce expatriate failure.39

Constraints on potential expatriates are: disruption of children’s education, spouse unwillingness to give up career, fear of losing visibility at the corporate headquarters and difficulty in re-absorbing the returning managers.40 Plans need to be made before departure to keep expatriates in touch with developments and headquarter’s ‘politics’ during their absence, to facilitate physical repatriation, cope with reverse ‘culture shock’ in work and social life and ensure repatriates will be able to return to suitable jobs.41

Headquarters managers need an awareness of the psychological impact, social and work life upheaval involved in expatriation and repatriation, so they can appreciate the difficulties facing returning expatriates who can take up to a year to readjust.42 High returner turnover means organisations are suffering a significant financial and human resource investment loss.43 ‘Organisational capability’ cannot be increased unless structured debriefings take place which enable both management learning to be disseminated throughout the organisation, and recognition to be given to expatriates for their experiences and learning.44

The ‘common denominators’45 of successful expatriation among European and Japanese MNEs are:

• a long-term orientation towards planning and performance appraisal;

• thorough preparatory training for the assignment;

• a wide-ranging support system for expatriates;

• overall suitability for working as an expatriate;

• company loyalty which restricts job mobility;

• an international orientation in the company as a whole;

• a longer history of dealing with expatriation;

• employee language skills.

Expatriation is not the only way to internationalise the organisation’s experience: cross-cultural seminars, extended business trips, international networks and project teams are also useful mechanisms, and they reduce loss of visibility and power in the corporate centre. Importing foreign nationals for an expatriate spell at head office may be the most significant trend for the future.46

13.3 Structures of international organisations

Business decisions about the way an international organisation is structured can be enhanced if a manager has an appreciation of:

• forces precipitating change in an organisational structure;

• issues requiring consideration when changing an organisation structure;

• the fit needed between strategy, structure and organisation culture;

• the current structure, desired restructuring outcomes and what the likely secondary effects are of both the restructuring process and the new structure, in terms of customer service and staff reactions;

• the additional factors influencing strategy and structure in a MNE:

• competition in several markets;

• currency and exchange risk;

• country characteristics — cultural issues;

• trading freedoms/cross-border restrictions, affecting goods and money;

• economic imperatives requiring economies of scale but political imperatives dictating adaptation to local conditions.

• the stages in internationalisation, which impact on management and especially HRM.

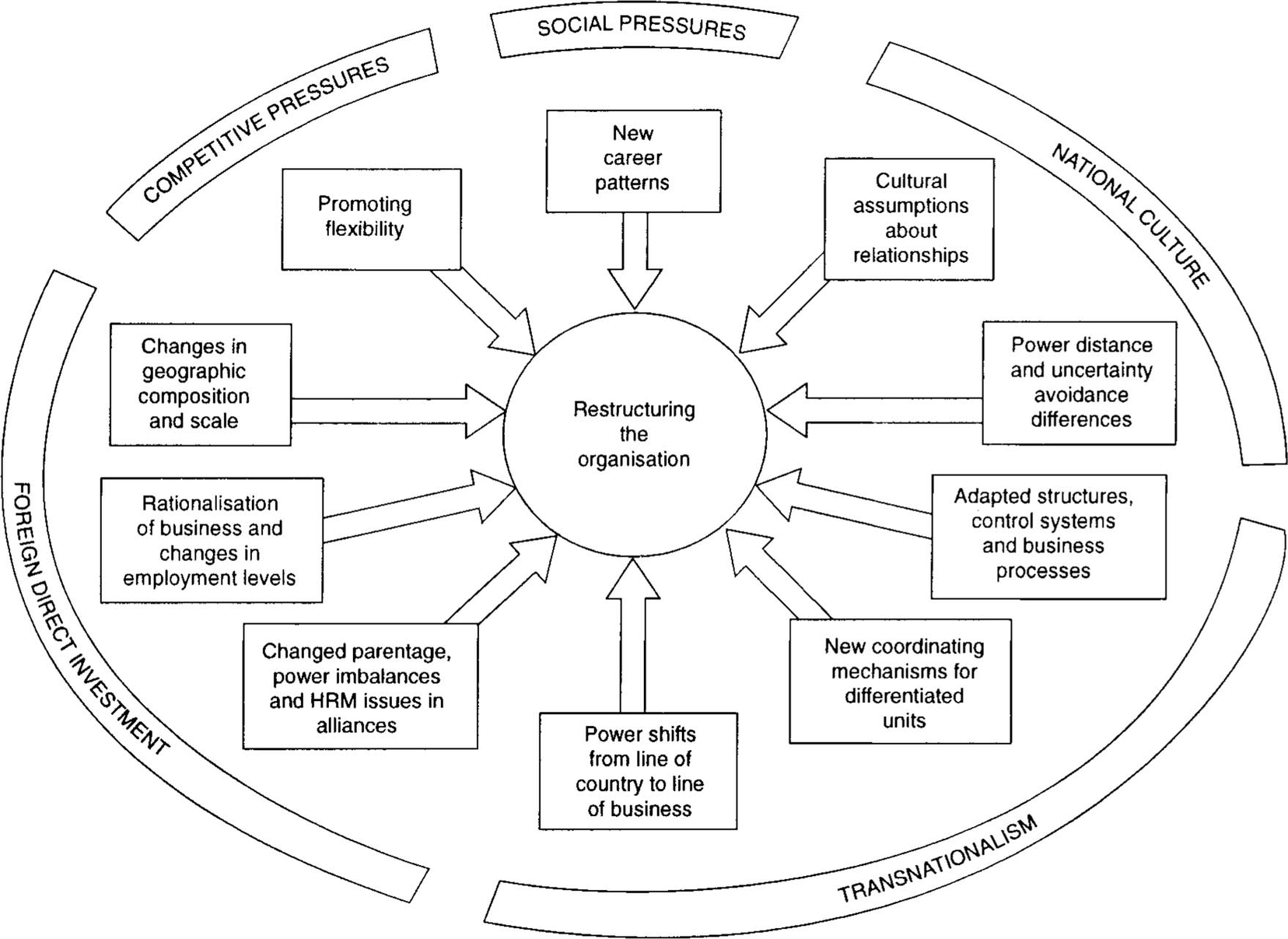

In the early stages of internationalisation, organisation structures tend to evolve in response to immediate market opportunities and constraints rather than in accordance with an articulated, comprehensive and rational plan. Later, significant environmental changes or business growth trigger consideration of the appropriateness of a structure. The pressures precipitating such changes in structure are shown in Figure 13.2.

Figure 13.2 The forces precipitating changes in organisation structure in Europe

Source: Sparrow, Hiltrop, European human resource management

Humes47 suggests analysing organisation structures along three dimensions:

1. Operational distance: the extent to which the constituent parts of the MNE are directed by the whole.48

2. Interacting organisational perspectives of: function, product, geography.49

3. Controlling management dynamics of: structure, staffing, shared values.50

MNEs based in different cultures and geographic areas tend to develop different combinations of the three dimensions suggested by Humes.51

• NORTH AMERICA: geography driven, structure stressed: control by formal systems and standards — ‘formalisation’.52

• WESTERN EUROPE: product driven, staffing stressed: careful selection and development of key decision-makers with good interpersonal and networking skills, posted to subsidiaries — ‘socialisation’.53

• EAST ASIA: major decisions taken at headquarters, a propensity to intervene in foreign subsidiaries — ‘centralisation’,54 function driven, shared values stressed.55

Regardless of the ‘Triad’ (i.e. North America, Japan, Western Europe) power groups from which the parent MNE originated, the structural approaches to dealing with international operations have some similarities, in so far as foreign subsidiaries tend to be run as separate entities to domestic product divisions in the early stages of internationalisation; subsequently, global product divisions develop. Over time, some convergence of structural approach, towards global product divisions, supported by continental organisations can be detected.56 When managing people across national boundaries and markets, the fact that products in some markets may be ‘rising stars’ but ‘dogs’ or ‘cash cows’ in others militates against a common structural and staffing approach for the whole organisation.

In terms of management mechanisms for resolving conflict between two people, national approaches vary: the British approach is to develop interpersonal skills and networks to allow the protagonists to settle the issue themselves in the context of the specific situation — the ‘village market’; the French resort to hierarchy — the boss decides — the ‘pyramid’; the Germans prefer comprehensive pre-set rules to govern the matter — the ‘well oiled machine’.57

There are several forms of MNE. Porter58 differentiates the industry types in terms of the nature of the competition they face — and thus the degree of interdependence of the parts of the MNE — on a continuum from ‘multidomestic’ to ‘global’. Competition in one country will be independent of competition in other parts of the company elsewhere in the world in the case of ‘multidomestics’, so they can be structured and managed as a portfolio of several domestic industries. Retailing is an example. In ‘global’ industries, such as aviation, competitive status in one country will affect that in others; they need global integration in their activities to capture the intercountry linkages needed to achieve competitive advantage. Facilitating the multifarious, multi-way, multi-level links between constituent parts of the global MNE is a key HRM role.

The form and extent of business internationalisation vary widely between and within organisations, so the implications for HRM will range from administrative to strategic involvement. HRM responsibilities may be with the HRM department, line management or another department. Contextual contingent variables will be prime determinants of who does what, and what is done in an organisation. Bearing in mind the ‘domestic multicultural’ aspect of international HRM,59 from an HRM perspective, organisations ‘internationalise’ before they establish overseas operations, as can be seen from the HRM model of internationalisation of an organisation. In practice, an organisation will not necessarily go through all the stages of the internationalisation model, and complex MNEs usually operate with a mix of several structural forms.

HRM model of internationalisation of an organisation

Conceptually, there are six stages in the full internationalisation of an organisation. At stages 1 and 2 the organisation has no foreign subsidiaries.

Stage 1 Multicultural management

• strategic focus: domestic market;

• any international sales or sourcing is via domestic-based intermediaries;

• local workforce ethnically heterogeneous, thus managers require multicultural awareness (customs, body language, etc.): HRM starts to internationalise.

Stage 2 Import/export

• strategic focus: domestic market, but some product export using overseas contacts;

• direct international resourcing of some materials/components, using overseas contacts;

• human resources may be imported to work in the domestic organisation (e.g. UK NHS imports nurses from Ireland and Finland and doctors from Germany);

• some work may be exported to people living abroad (e.g. outsourcing programming to computer programmers in India).

From Stage 3 onwards, the organisation has foreign subsidiaries. The following parts of the model delineate international organisations by their approach to control and the degree of globalisation of strategy, drawing on work by Bartlett and Ghoshal.60

Stage 3 International

• knowledge transfer is parent to foreign subsidiary;

• ‘export’ approach to strategy;

• ethnocentric staffing approach;

• parent central control.

Stage 4 Multinational or multidomestic

• portfolio of many foreign companies, run as discrete national entities;

• control decentralised on local matters, so sensitive to national differences;

• polycentric staffing approach.

Stage 5 Global

• global strategies;

• tight centralised strategic control at parent hub.

Stage 6 Transnational

• local flexibility but global integration;

• ability to manage across national boundaries;

• ‘ability to link local operations to each other and to the center in a flexible way, and in so doing, to leverage of those local and central capabilities’;61

‘Networks’62 and ‘heterarchies’63 are elaborations on the transnational form rather than new models. They feature:

• multiple strategic centres, with coordinating responsibility for specific activities64 (e.g. design centre in Italy, information technology centre in the UK);

• a network of intra-organisational relationships at several hierarchical levels between the organisation’s parts; and a network of inter-organisational relationships with competitors and stakeholders;

• a focus on coordination through interpersonal relationships, rather than just by structure and procedures;

• complex management reliant on interpersonal skills of staff.65, 66

A transnational is not so much a specific physical structural form, but rather, a way of thinking. As well as dealing with the HRM issues arising in earlier stages of internationalisation, developing a transnational presents special challenges for the HRM function:

• fostering global thinking in top managers;

• creating ‘formal’ structures which facilitate and do not impede the operation of a matrix in the mind;

• selecting and developing staff with a global mindset who are able to cope with ‘cluster’ rather than hierarchical structures and who have the interpersonal skills to operate in a network way;67

• devising effective motivation, reward, appraisal and future development programmes: encouraging a learning organisation;

• facilitating change management;

• fostering values and a structure supportive of the transnational strategy;

• developing, in conjunction with information systems specialists, appropriate systems and information flows to underpin the networking.

Joint ventures generate particular management demands:

• the creation of appropriate HRM policies, mechanisms and structures: those of one partner/a mixture/a new approach?;

• coordinating operations run by people from different companies, accustomed to their parent company way of doing things;

• developing an appropriate culture for the joint venture.

The HRM role in international HRM

For support and primary activities in the value chain, and for the value chain as a whole, the HR function undertakes direct, indirect or quality assurance activities, each of which plays a different role in gaining competitive advantage.68 Which activity is most critical for an HR department will depend on the industry in which it is operating and the structure of the organisation, and whether the HR department is the parent’s or a subsidiary’s.

The role of the ‘international’ HR manager varies considerably according to the development stage of the international operations. HR interventions must match the needs of the organisation at the time. The more complex the organisation structure, the more the HR role tends towards focus on ‘soft’ HRM issues: management development, cross-cultural awareness, reinforcing corporate culture.

Schuler and Dowling69 identified from their 1988 survey that the major challenges for the international HRM function in strategic planning included:

• identifying top management potential early;

• identifying critical success factors for the future international manager;

• providing developmental opportunities;

• tracking and maintaining commitments to individuals in international career paths;

• tying strategic business planning to human resource planning and vice versa;

• dealing with the organisational dynamics and multiple (decentralised) business units while attempting to achieve global — and regional — (for example, Europe-) focused strategies;

• providing meaningful assignments at the right time to ensure adequate international and domestic human resources.

The international HR manager needs:

• to shed ethnocentricity and think globally, and facilitate this in others, as failure to recognise HRM differences in different countries often causes major problems;70

• to have a broad understanding of the MNE’s foreign operations and their importance to the company plus foreign experience gained in a line, as opposed to subsidiary, HRM department, role. However, international HR professionals spend about 54 per cent of their time on pay issues and only 10 per cent on strategy;71

• to have the abilities and personal skills to gain acceptance in involvement in strategic decision-making at corporate level.72

The competencies needed by international HR practitioners to develop an effective career in international HRM have been identified by the IPD from a study of 500 companies in 14 countries, and produced in a guide (1995).73

13.4 National cultures

National or ethnic culture is different from organisation culture. At national level cultural differences are mostly in values — absorbed during childhood from the family, rather than in practices; at organisation level, differences are mostly in practices — learnt at the workplace as an adult.74

All managers operating internationally, even ‘occasional parachutists’, need guidance on observable behavioural variables: meeting, greeting, eating, negotiating, etc., even if they have limited time to consider the underlying values which drive the behaviour. Operating cross-culturally, managers need to predict reactions to their behaviour or actions and interpret those of others: ‘What will be the reactions if I manage this situation in a certain way or introduce that HR practice in our foreign subsidiaries?’ Unless the gap between the cultures is small, this is not possible unless the manager appreciates the foreign contacts’/employees’ underlying values, beliefs and assumptions which will govern their behaviour. In practice, understanding these requires an appreciation of how they differ from one’s own cultural influences; but to use one’s own ethnocentric cultural orientation as a basis for behavioural prediction or interpretation in other cultures leads to misunderstandings and business failures, as can be seen in the Lehman example. The manager needs to be able to switch from a ‘self’ to an ‘others’ orientation.

Lehman Brothers have proceeded to issue writs in the Chinese courts against two state-owned subsidiaries for non-payment of debts. In the commentaries by the parties and the media, one can be forgiven for gaining the impression that both sides in this dispute operated from a basis of trust. The Americans trusted the PRC firms would pay but the PRC firms trusted the Americans would not make insensitive demands.75

Characteristics of culture

Cultures are integrated, coherent, inter-related systems; if one aspect changes, it affects other aspects of the culture. Culture is not genetically inherited, but learnt. It can influence biological processes and reflexes.76 None the less, there are certain ‘cultural universals’, i.e. human needs requiring satisfaction, which are common to all cultures, such as;77

• economic systems;

• family and marriage systems;

• education systems;

• social control systems;

• supernatural belief systems.

A greater empathy for, rather than criticism of, cultural differences, can be developed if a manager is aware of the similarities within societies; this makes criticism of the differences less likely as they are seen as environmentally determined solutions for human problems faced throughout the world.78

In discussing features of national cultures the distinction must be made between characteristics of the individual (personality) and characteristics which are commonly found throughout that society (culture). Individuals in every culture vary enormously one from another, so should be approached as unique human beings, and without making stereotypical judgements about them in advance. Culture does not represent the ‘average citizen’ or a ‘model personality’; rather, it is a set of likely reactions, statistically found more frequently, in that society of people with common ‘software of the mind’.79 These generalisations about likely reactions are heuristic (general guides which help discovery and understanding) and not invariable or precise reflections of reality.80 The normative limits of ‘acceptable behaviour’ are in any case hard to define.

Cultures are characterised by continual change, albeit at different speeds at different times, in response to: internal pressures of discovery, and invention; and external pressures of selective diffusion and adaptation. The speed of adoption of a new cultural item, whether it is a material object, a technology, a behaviour, a practice or an attitude will be heavily affected by five variables81 (see Table 13.1).

Table 13.1 Factors influencing the adoption of innovations

Source: adapted from Rogers, 1971

Objects and technology are much more likely to be adopted than behaviour, social patterns and belief systems, because they can be seen to be useful by several people and do not necessarily threaten basic values. Imported management practices may call for changes in basic values or at least behavioural variations which are inconsistent with deeply held beliefs: they may be rejected or simply not work. For example, the introduction, into a culture with strong communitarian values, of pay related to individual performance, challenges the very fabric of the culture by introducing ‘competition’ between members of the ‘in group’, whose effective functioning has hitherto been by means of the group operating as a harmonious whole.

A practical approach to transplanting management practices across cultures requires assessing the impact of the practice on cultural values. If there is likely to be a clash, the ‘Concept, Brand and Contents’ approach can be used. The Concept of what the MNE wants to achieve is internationally transferable, for example, pro-active employee performance management. The Brand name or label for the practice can be varied to ensure acceptability locally, as can the ‘Contents’ of the employee performance package. The ‘what’ that needs to be achieved is common; the ‘Brand’ or the ‘label’, plus the specific ‘Contents’ — means to achieving the desired outcome — can be varied.

Culture: common problems, different solutions

Hofstede,82 analysing work-related values data, confirmed the existence across cultures of common problems but different habitual methods of problem resolution. The original four common problem areas or ‘dimensions’ related to:

1. Power distance. This dimension addresses the question: who is accepted as having the power to decide what?83

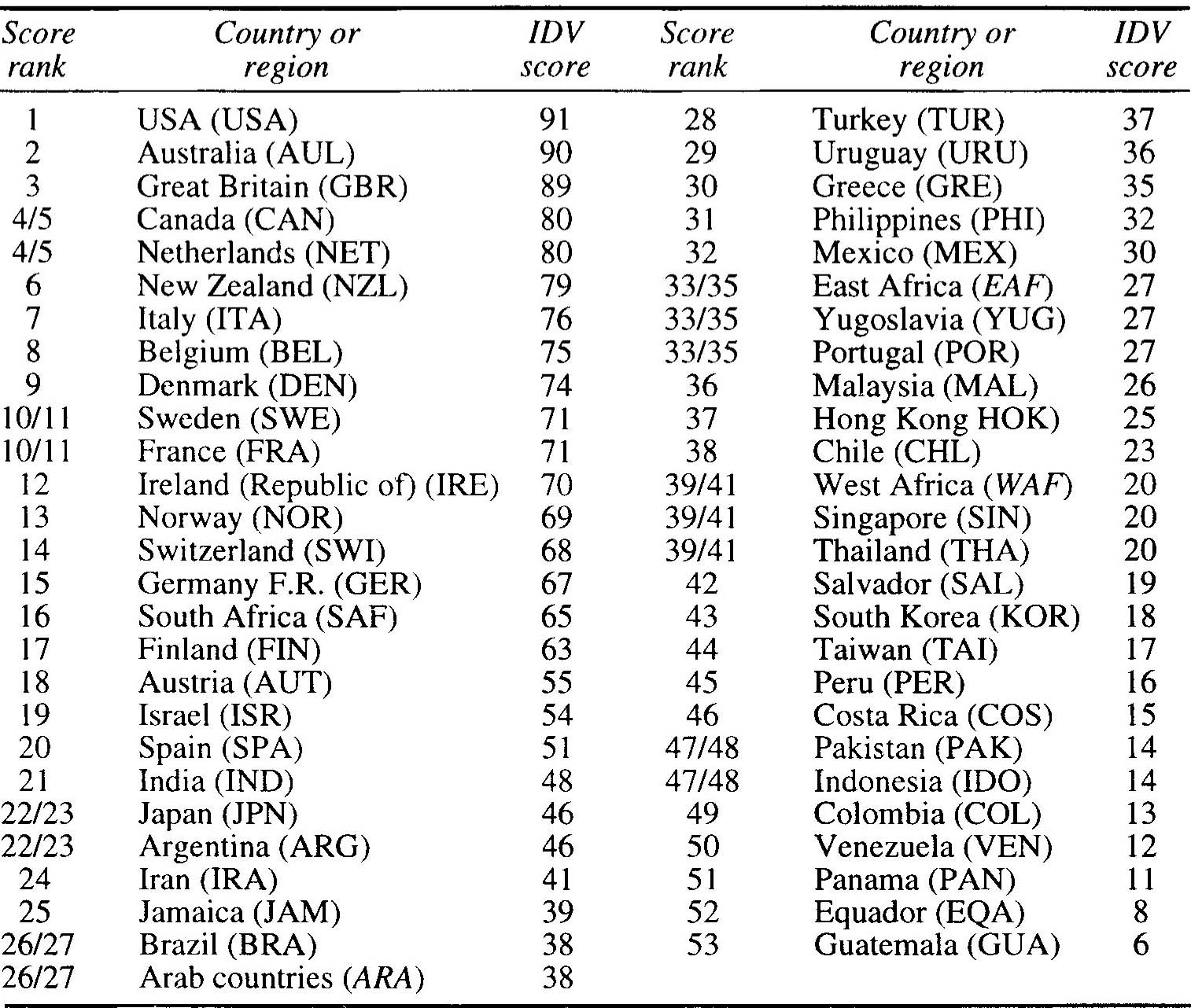

2. Individualism, with its opposite, collectivism. The USA is a highly individualistic society, Japan is collectivist (see Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 Individualism index (IDV) values for 50 countries and 3 regions

Source: Hofstede, Cultures and organizations

Note: Initials in brackets are country codes used in Figure 13.3 (opposite).

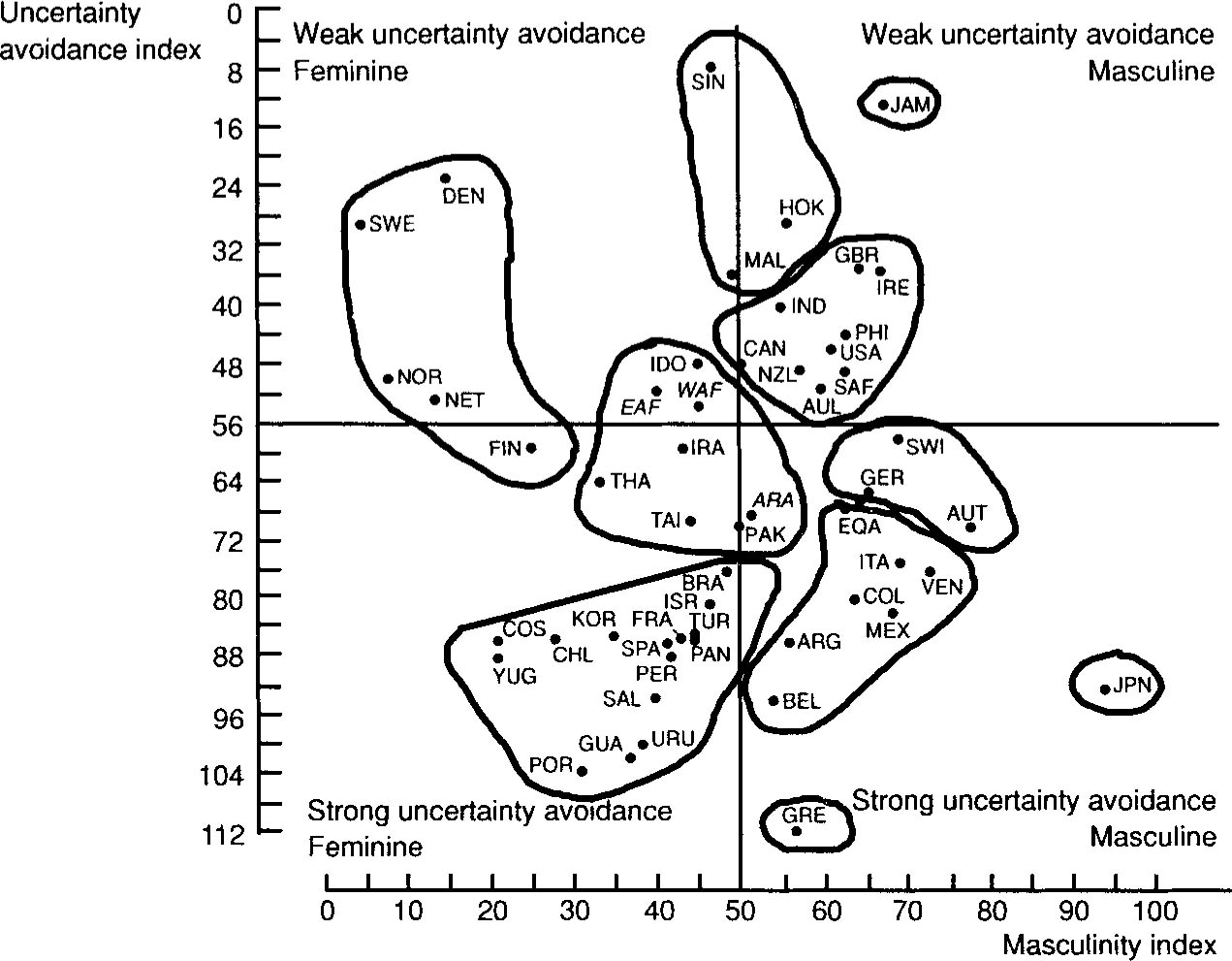

3. Masculinity, with femininity as the other pole, is ‘the desirability of assertive behavior against … modest’.84 Masculine societies attach importance to earnings, recognition, advancement, challenge; feminine ones to good boss and harmonious colleague relationships, employment security and living in a desirable area (see Figure 13.3).

Figure 13.3 The position of 50 countries and 3 regions on the masculinity/femininity and uncertainty avoidance dimensions

4. Uncertainty avoidance which, poled as weak and strong, concerns the extent to which people feel threatened by unknown situations, lack of structure and ambiguity, so seek to avoid the anxiety these create by operating according to rules or diktats of superiors.85 (See Figure 13.3).

Hofstede’s first and last dimensions affect thinking about organisations themselves. The second and third dimensions concern thinking about people within organisations.86

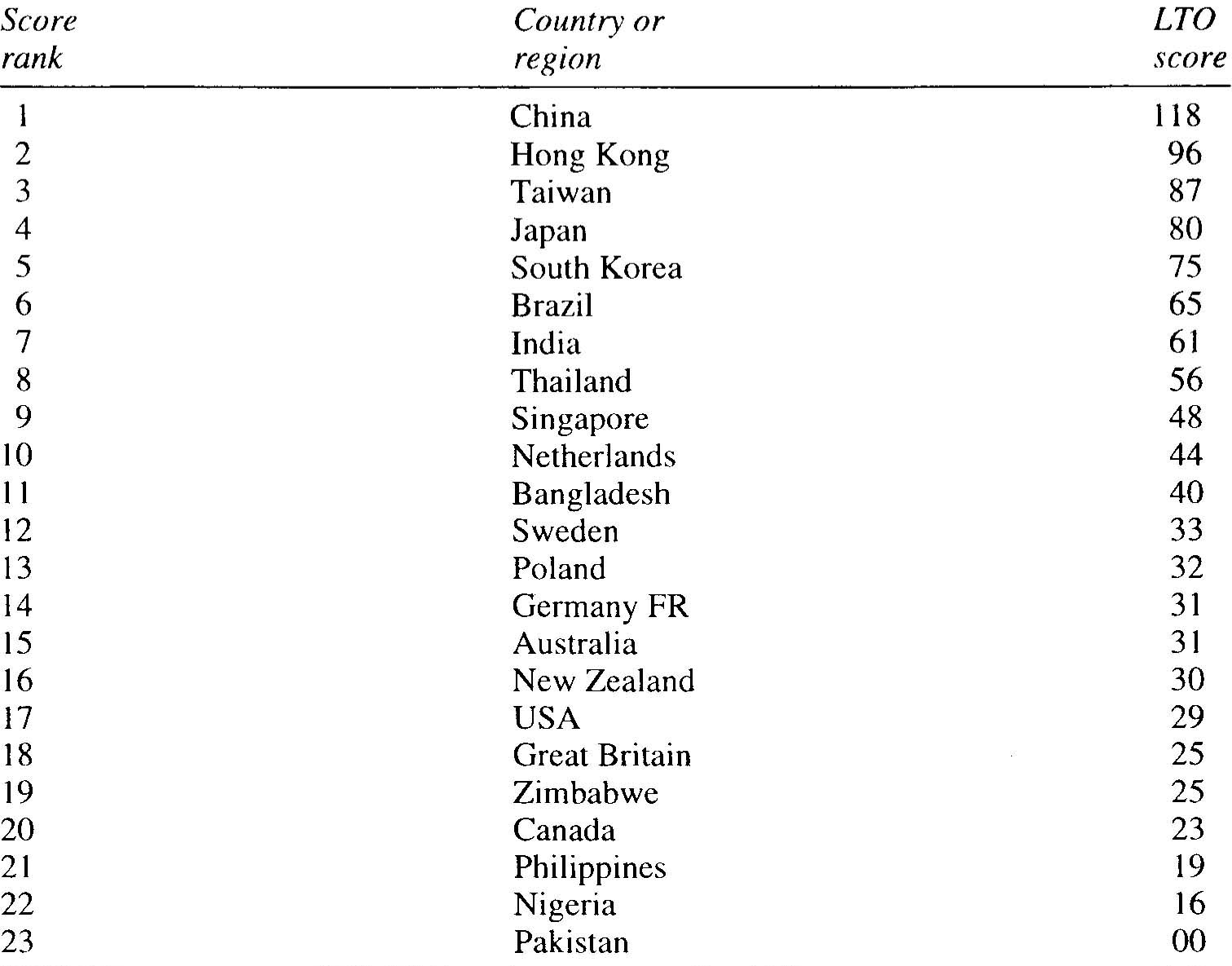

The questions in Hofstede’s87 original survey reflected the ‘Western’ cultural bias of the survey compilers: so Michael Bond compiled a survey with questions based on Eastern values, the Chinese Value Survey (CVS). From this, a new dimension emerged, which reflected at both poles aspects of traditional Confucian values, so was named ‘Confucian dynamism’.88 Confucian dynamism has poles of long-term orientation (LTO) and short-term orientation (STO). The LTO pole reflected values seen as dynamic and future-orientated: persistence and perseverance, ordering relationships by status and observing order, thrift, having a sense of shame-and thus of obligation to carry out one’s duties (see Table 13.3). The STO pole values were seen as relatively more static and past and present-orientated: personal steadiness and stability, preservation of ‘face’ (yours and that of others within your group), respect for tradition, meeting social obligations, reciprocation of greetings, presents and favours.89 The importance of Hofstede’s, Bond’s and Hampden-Turner and Trompenaar’s (1995)90 work for HR managers is that in assessing, for example, the likely transferability of management practices and structures, rather than rely upon single country descriptions or dual country comparisons, data are available from the same base across several countries to provide the guiding heuristics a global MNE may need. Because a country scores high on one dimension, it does not mean that the characteristics of the other pole are unimportant in that culture, so can be ignored; merely that the one pole tends to be more important when forced choice questions are used. (What is involved in the relationship of a ‘good’ boss and a ‘good’ employee differs between cultures. Failure to appreciate these differences can be problematic for managers dealing with any HRM issues such as structuring, motivation, decision-making and remuneration in foreign subsidiaries, and for those managing a foreign workforce who expect loyalty systems and motivational approaches to be those they experienced back home).

Table 13.3 Long-term orientation (LTO) index values for 23 countries

Source: Hofstede, Culture and organizations

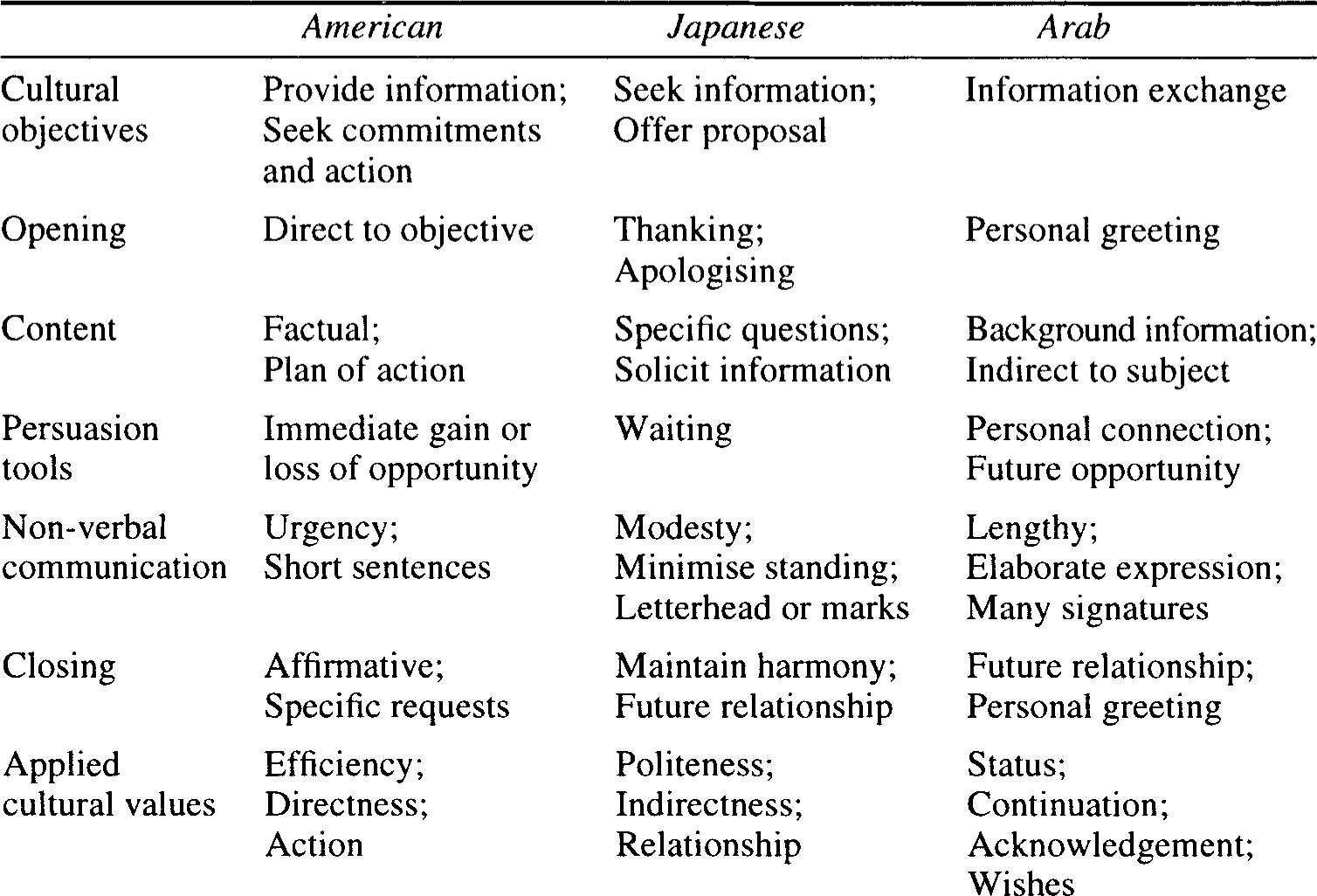

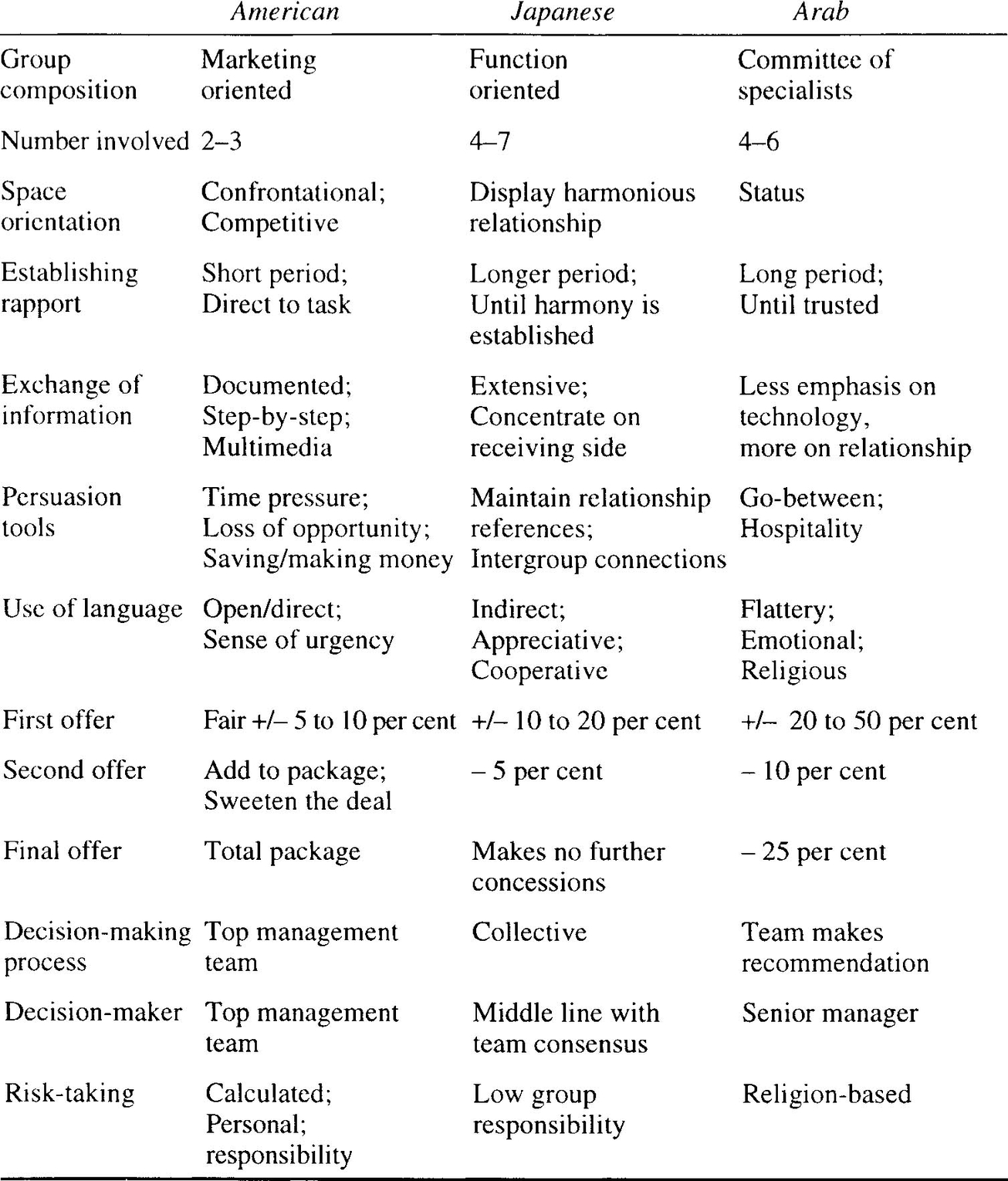

The Elashmawi and Harris91 book offers useful heuristics for three specific cultures: American, Japanese, Arab, including information about basic issues involved in dealing with people cross-culturally: meeting, greeting, letter writing styles, introduction approaches, exchanging cards, disciplining, negotiating, running training sessions, etc.

Nations vary in their view of the importance of, and the linkages between, the past, present and future. Americans view time sequentially: as having no links between the three time dimensions but with a focus on the future; Japanese and Germans tend towards a synchronous view of time with the three dimensions tending towards being condensed; the French place a greater importance on the past than the other two dimensions (see Figure 13.4). Circle size shows importance. Circles placed apart reveal sequential thinking. Circles overlapping reveal synchronous thinking, with a seminal future and remembered past, present, here and now. The characteristics of sequential and synchronising managers identified by Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars are given in Table 13.4.

Figure 13.4 How managers in 12 nations conceived of Past (left), Present (centre) and Future (right)

Source: Hampden-Turner, Trompenaars, Seven cultures

Table 13.4 Characteristics of managers with sequential or synchronizing perceptions of time

Source: Harnpden-Turner, Trornpenaars, Seven cultures

Charles Hampden-Turner and Fons Trompenaars (1995)92 identified seven valuing processes fundamental to wealth creation in organisations, and found national differences in how the dilemmas posed by these processes were resolved (see Table 13.5). Some cultures were ‘universalist’ – wanting things to be decided by universal, codified and ‘one rule for all’ principles – these were Anglo-Saxon and Northern European countries. ‘Particularists’ – France, Italy, Japan, Singapore and Belgium at the other end of the continuum – tended to value friendship and personal relationships above following rules, or rather the Japanese concept of what was the ‘rule’ or guiding principle for behaviour differed from the typical Western concept.93

Table 13.5 Valuing processes fundamental t o wealth creation and the dilemmas they pose

Source: constructed from pp. 5-12, Harnpden-Turner, Trornpenaars, Seven cultures

The Japanese concept of organisation is a harmonious network of particular people; the American view is tasks, systems and functions. The United States is a highly analytical culture, valuing deconstruction, facts, ‘the bottom line’ above a holistic integrative approach which is favoured by Japan, Singapore and France. With such differences in national business values, the manager should not use norms for employee values, attitudes and satisfaction obtained in the parent country as yardsticks against which to measure foreign subsidiaries’ responses in employee attitude surveys. International survey organisations have developed country-specific norms.

However, Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars perceive value resolution to be a circular process with one country focusing on one aspect of a value as a means to achieve an end which another country sees as the means (not the end) to achieve their end, i.e. what the first country views as the means. This is illustrated in Figure 13.5.

Figure 13.5 The circular nature of value resolution

13.5 Business values and ethics

If business values are accepted as being largely culturally determined, whose business values should a MNE apply? This point is important, for while business values can be examined without making judgements about whether the values are right or wrong, good or bad, business values applied to real situations become business ethics, which are prescriptive and carry with them the implication of a prior judgement of ‘rightness’. The issue becomes, whose business values is it right to apply? The answer to this is far from straightforward; several options are possible.

1. Values pertaining at the parent company headquarters. This is an ethnocentric ‘export’ approach to ethics, workable where there is a close match between the moral ethos in the parent and host countries, but impracticable where there is a significant difference.

2. Values of the host country. This polycentric ‘when in Rome do as the Romans do’ approach to ethics, while sensitive to local differences, creates several different ethical approaches to business within the MNE, thus the opportunity for inconsistency, bad publicity and opprobrium in the eyes of the stakeholders who might wonder why, for example, the MNE uses child labour overseas but decries it back home.

3. Values generated by the MNE after careful consideration of the issues, consultation with subsidiaries and managers operating internationally. These values transcend the moral ethos in any particular country – a geocentric approach to ethics, yet have to be formulated taking into account a range of moral climates, the needs of employees operating within them, and stakeholder sensibilities.

4. Adherence to local law. Some see the aim of business as profit maximisation and what matters is law, not ethics.94 While the rationale for this is different from the polycentric approach, potential outcomes are similar. This presupposes, incorrectly:

(a) that all behaviour is governed by law, or any behaviour is permissible if law does not govern it; and

(b) that it is, in fact, custom and practice for law to be obeyed in each country.

5. Ignore the issue, leave it up to employees themselves abroad to decide on how they behave. Apart from the potential for inconsistency, this seemingly empowering approach to ethics is usually an abrogation of organisational responsibility in the face of

‘difficult’ issues. For a manager operating overseas, resolving ethical dilemmas can be a lonely business, particularly in an organisation in the early stages of internationalisation, which has yet to have had enough overseas experience for managers at parent head office fully to appreciate the problems. Overseas managers can feel isolated, unsupported and ‘damned if they do and damned if they don’t’ when their actions generate adverse publicity and a punitive MNE reaction.

MNE attitudes to supporting foreign posted staff with ethical dilemmas vary between organisations, according to their stage of internationalisation, the extent of their previous experience of operating internationally, the subject of the ethical dilemma, and the attitude of the boss back at the parent.

What constitutes appropriate ethical conduct may develop through unwritten norms evolving through group interactions; but in a MNE norms will differ between locations. Hence written codes of conduct, openly adopted, published and proactively communicated, have been developed by many companies to address ethical issues.

To be effective, they require the active involvement and support of senior managers. This means not just words for PR purposes but following through with action.

In 1987, Bob Haas, the Chairman and CEO of Levi Strauss & Co., had a top management retreat to consider the development of long-term business values and produced:

• a Mission Statement – why the company is in business;

• a Business Vision Statement – what it wants to be;

• an Aspiration Statement – how it can meet its goals.

These reflect core corporate values which, as much as cost, competition and efficiency, influence business decisions. The company’s approach to difficult ethical issues is reflected in how they dealt with the issue of their Bangladesh sub-contractors employing female workers under 14. If the girls had no jobs they would be likely to become prostitutes to support their families. After discussions with the sub-contractors the issue was resolved by Levi Strauss paying for educational tuition fees, books, and school uniforms until the girls reached age 14; the sub-contractors paid the girls whilst they were attending school.95

A MNE could take a two-tier approach of generic global values and locally specific ones,96 with the former perhaps including ‘marketing, information policy, environmental protection, animal experiments, research policy’.97 The two-level concept accommodates the ‘think global, act local’ principle but in practice may not make the issue of corruption, pervasive in many countries, any easier to deal with.

Mahoney (1995)98 sees all commercial bribery as being bad for business, bad for the participants, bad for the society in which it occurs, but what constitutes corruption differs between societies. Managers operating abroad need some guidance on what is a ‘gift’, a ‘bribe’, an ‘extortion’ payment. The following distinction is helpful:

• bribing is paying people to induce them to behave unethically or to gain some particular advantage; and

• extortion is paying people to do their jobs; i.e. making payments not required by law but which individuals demand, albeit subtly, for ‘the proper performance of a task not its perversion’.99

The former is hard to justify ethically. The latter is usually of more concern for people operating internationally. Some ‘officials’ with whom the business person has to deal may be poorly paid and see the only way to acquire more money as being to delay performing their job functions until given financial inducement. Paying such extortion, just to get normal business transacted is seen as less ethically reprehensible than paying a bribe, but Mahoney sees it as justifiable only if all the following four conditions prevail:

1. There is no other way of doing one’s business in that country.

2. The payment is not to persuade someone to do wrong; rather, it is to stop threats or stop them from doing wrong.

3. The business person is engaged in legitimate and lawful business which is of benefit to wider stakeholders in the society and the economy, than just the immediate participants in the business.

4. Concomitantly, the business person is trying to do everything possible to prevent the practice of such extortion; for example by trying to ensure that the officials in question are paid a living wage.100

Snell (1995)101 identifies four types of ‘psychic imprisonment’ which can restrict a manager’s ability to solve ethical dilemmas.

1. limited ethical reasoning capability;

2. stereotypical assumptions about organisation structures, power and responsibilities;

3. lack of power or responsibility in the organisation;

4. a moral ethos incompatible with the individual’s own stage of ethical reasoning.

The first two types of psychic imprisonment are restrictions internal to the manager, while the latter two are ‘moral mazes’, mainly external to the individual.

Moral dilemmas arise if the manager is pressured to enact a lower stage of ethical reasoning than her/his habitual mode. The manager’s role in ethical matters could usefully include:

• identifying the real ethical dilemmas staff encounter, operating in their organisation’s foreign environment;

• stimulating discussion, including the views and problems of expatriate and HCN staff, on dilemmas, possible solutions/standards, organisational support, and ethical codes;

• contributing, at senior level, to the development of appropriate ethical codes;

• code communication and explanation;

• setting an example by personal adherence to the organisation’s ethical codes;

• in the case of a large organisation with substantial foreign operations or frequent buying/selling contacts overseas, pressing for the appointment of an ‘ethics ombudsperson’ to whom, in total confidentiality, staff could apply for guidance on code interpretation and action, in the light of specific problematic situations which have arisen;

• ensuring that appraisal, promotion and reward mechanisms, and the way they operate in practice, do not favour unethical behaviour: management mechanisms and actions must be consonant with ethical statements;

• selecting staff operating across national borders who are best able to cope with the ethical dilemmas likely to arise in the particular host cultures.

Managers may also become involved with disciplinary action against ethical code breakers. They also may have to deal with ‘whistle blowers’ who, adhering to the organisation’s ethical code, embarrassingly publicise the unethical behaviour of others or who, personally operating at a higher level of ethical reasoning than the organisation, publicise what, from their perspective, is unethical behaviour.

Both situations pose difficult dilemmas for the manager. In an organisation operating domestically, business ethics (both personal and organisational), organisational politics, personal power/survival, and career, are not easy imperatives to balance. Managing in an international organisation, the considerations become more complex.

13.6 Culture: language and non-verbal communication

When business deals are conducted between people speaking different languages, it is vital that both parties have the same conception of what is agreed. This requires translators with up-to-date knowledge of the language, the type of vocabulary being used and its correct situational usage: speakers of ‘social’ Russian would have difficulty with business or engineering terms, and their misapprehensions could have disastrous consequences.

When simultaneous translation is required, the best approach is to have two translators: each to translate into their mother tongue from the foreign language. Legal documents present problems requiring specialist translators, not least because the legal concepts of one nation may not be those of another, yet the implications have to be understood by both parties.

A culture evolves words to reflect the needs of its environment so may not have the vocabulary to express a concept related to a different one. For example, in the early 1990s, the Chinese definition of ‘marketing’ – in a UK published Chinese/English dictionary — ill expressed the meaning of the Western concept, creating bewilderment for PRC students studying business in the UK. Before the PRC economic reforms ‘marketing’ was not a relevant concept to the PRC. A recommended approach, for those operating in a foreign language of which they have imperfect knowledge, and coming from a very different culture, is to look up the meaning of a word in the same language dictionary of the foreign language: the word will be explained in the context of that culture.

Just as connotations of a word vary between cultures, slang and euphemisms provide additional pitfalls. The business consequences of linguistic faux pas may be more serious than the wry amusement occasioned in a Moscow hotel by a notice stating: ‘If this is your first visit to the USSR you are welcome to it’.102

‘He has no power’ is a typical Japanese insult about a boss, whereas ‘I don’t like him’ is typical in some Western cultures.103 ‘I don’t like him’ might indicate antipathy based on objections to a boss’s non-job-related personal characteristics, but it is more likely to refer to antipathy based on shortfalls in job-related interpersonal or technical skills. To Japanese managers a boss is usually characterised by power rather than job skill; but Western managers see job skill as the predominant characteristic of a boss.104 However, the connotations of the concept of a boss’s ‘power’ differ between nations. To the Japanese, the boss is powerful because he has harmoniously integrated the particular resources of which he has charge; this – to a UK mind – infers job skill. Hence, both phrases, while saying different things, mean the same: ‘the boss is no good at his job’. However, to the Westerner, power has connotations of ‘a subversive influence in which the moral order, by which the best performers rise to the top, is corrupted by the private agendas of empire builders and power seekers’.105

Linguistic styles vary between nations. Concise and to the point is an American preference; Arab speakers use what, to an American, seems to be an over-elaborate rhetorical style. To an American, excessive politeness, thanking and apologising characterise Japanese communication. The international manager needs to be able to interpret linguistic styles in their contexts.

Japanese has several words for ‘no’. Other East Asian and Arab cultures have several ways of indicating a negative response without being as direct as saying a flat ‘no’. Such circumlocution, totally understandable within their cultural contexts, where saving the other’s face is a way of showing respect and maintaining harmony, can be frustrating to, or misunderstood by, many North American or UK managers. However, polite circumlocution — but different polite circumlocution — is also used in English: what does ‘I’m not too keen on this idea’ really mean? Elashmawi and Harris’s (1993)106 table of cultural contrasts in written business communications in America, Japan and Arab countries, offers helpful heuristics to interpreting linguistic styles (see Table 13.6).

Table 13.6 Cultural contrasts in written business communications

Source: Elashmawi, Harris, Multicultural management

Implicit models of boss-subordinate communications vary between cultures:

A Western management perspective assumes that the subordinate’s willingness to initiate upward communication indicates a ‘healthy’ relationship reflecting high trust in the boss as well as openness. This position may need to be tested in Southeast Asian organisations, which generally value authority in superior-subordinate relationships. Upward communication could also mean that the employee may criticise or challenge his/her boss’s decisions. This could be perceived as not according the boss the respect attached to his/her status.107

Some 65 per cent of communication is non-verbal;108 the meaning we attribute to nonverbal stimuli is defined by our culture, which leaves plenty of room for misunderstanding in cross-cultural exchanges.

Hall (1959, 1966, 1976)109 classified cultures as:

• ‘low context’, where the transmission of explicit verbal messages constitutes the majority of the communication (e.g. Western societies);

• ‘high context’, where the physical environment, what they know and have internalised are used, as much as words, to understand the situation (e.g. Chinese culture).110

High context cultures tend to be polychronic, compared to Western cultures.111

Non-verbal communication can include:

• paralinguistics: the non-verbal use of the voice, e.g. pitch, rate of speech, volume;

• kinesics: movements, e.g. facial expressions, hand and limb gestures;112 gait, posture, eye contact, touching;

• proxemics: the distance between people with which those concerned feel comfortable; significant national differences exist in what is deemed appropriate for intimate, personal, social and public space between people;113

• silence;

• olfaction (scents or smells such as perfume);

• colour and graphic symbols;

• clothing, hairstyles, cosmetics and accessory artifacts: jewellery, fly whisks, etc.;114

• chronemics: the perception and use of time.115

In considering non-verbal communications, Ferraro116 warns of the dangers of:

• overgeneralising;

• assuming that all non-verbal cues are of equal significance within a given culture, and apply across both genders and all social levels;

• over-emphasising the differences between cultures in non-verbal communications;

• believing the consequences of misunderstanding non-verbal cues are always catastrophic.

Divergence or convergence in national cultures?

Child (1981)117 found that those studies indicating convergence of national cultures mostly concerned organisation structures and technology used; divergence theories focused on behavioural differences. Hofstede (1994)118 believes the thesis ‘national cultures are becoming more alike’ is based on observation of the more superficial layers of culture like ‘practices’: the way people dress, what they buy, films they watch, sports and leisure activities they undertake; deeper values between nations continue to differ significantly.

there is very little evidence of international convergency [in cultural values] over time, except an increase of individualism for countries that have become richer. Value differences between nations described by authors centuries ago are still present today, in spite of continued close contacts. For the next few hundred years countries will remain culturally very diverse.119

For many years to come, cultural awareness training will thus remain an important issue for businesses operating internationally.

Training for cultural awareness

Organisations lacking resources and time to acculturate staff operating internationally ‘in house’ might use bodies such as the UK-based Centre for International Briefing, at Farnham, Surrey, who offer pre-departure acculturation programmes, tailored to specific needs, covering almost any country in the world.

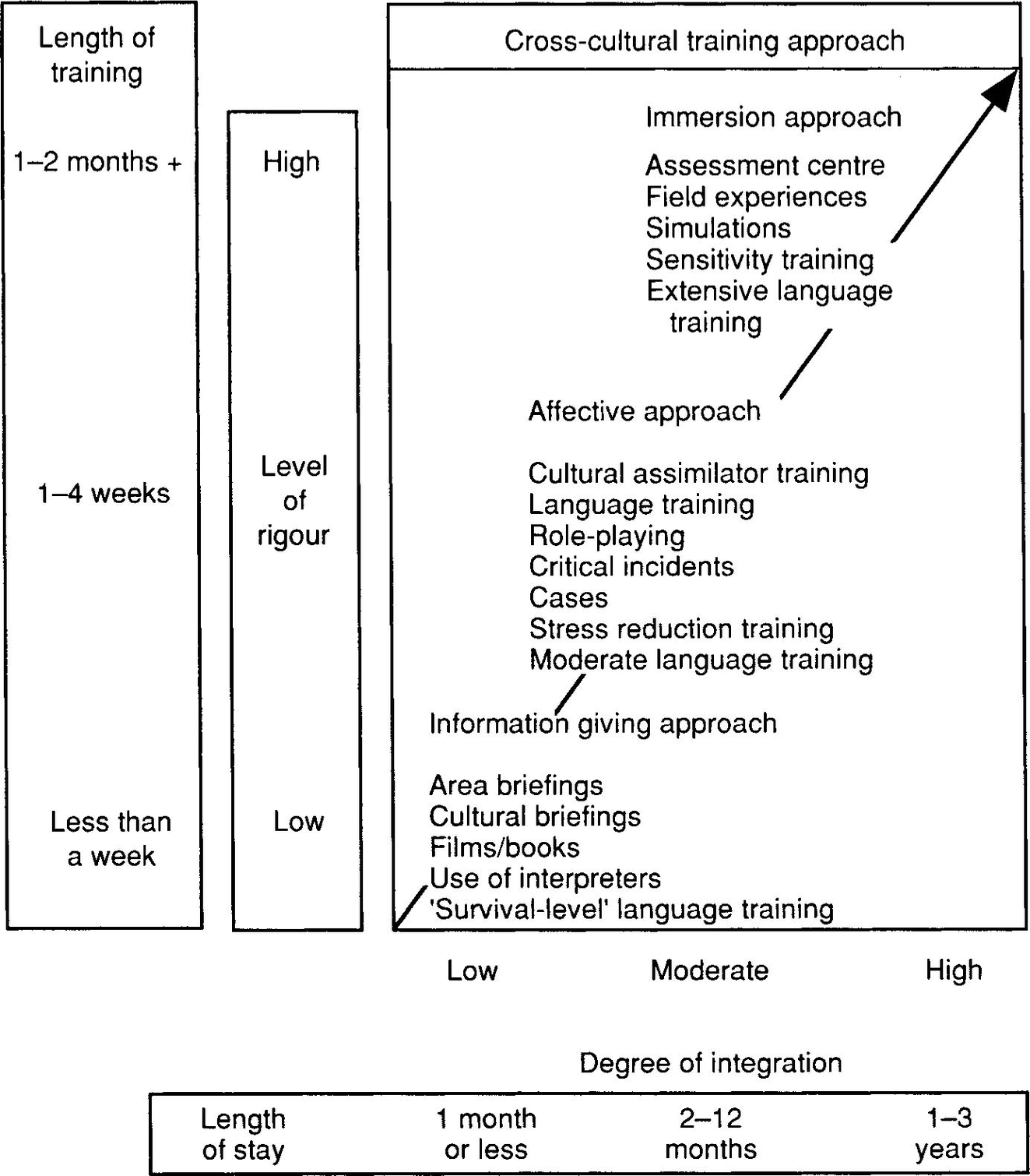

Who should be trained, in what, to what depth and for how long are functions of the extent of interaction required in the new culture and the similarity between the employee’s own culture and the new one.120 As for any training or development situation, there are a range of training methods which can be used. Figure 13.6 offers a framework to identify cross-cultural training needs.

Figure 13.6 The Mendenhall, Dunbar and Oddou cross-cultural training model

Source: Mendenhall et al., Expatriate selection

In-depth country-specific immersion programmes may be suitable for expatriates and those destined to have a long relationship with a specific country, but for ‘occasional parachutists’121 likely to visit a range of different countries for short periods, information-giving sessions or an understanding of cultural components, which can then be applied to a new situation, are more appropriate.

However, as Robinson (1983)122 points out:

the successful international manager is one who sees and feels the similarity of structures of all societies. The same set of variables are seen to operate, although their relative weights may be different. This capacity is far more important than possession of specific area expertise, which may be gained quite rapidly if one already has an ability to see similarities and ask the right questions — those that will provide the appropriate values or weights for the relevant variables.

13.7 Labour market issues

The labour market issues which need consideration when deciding upon the location of a new foreign unit are:

• Is labour of the required type, or which can fairly easily be trained, potentially available?

• What is the employee relations climate?

• What are wage levels, associated social costs of employment, expected or required terms and conditions, and inflation rate trends?

• What local or central government laws and regulations affect employment?

• What is the prevailing attitude amongst HCNs to work, and working for a foreign company?

• What are the costs, advantages and disadvantages of living and working in that location for potential expatriates?

• What are the potential costs of entry and exit in the labour market in that location?

• What work permit and other restrictions affect labour mobility: both HCN mobility within the country and the ability of foreigners to work there?

For example, social costs of employment are higher in some EU countries than in others; labour mobility is restricted within the PRC; in Russia some people are oriented to work with the lowest productivity possible and are uninterested in the work to be done.

Career patterns vary between countries. In Japan, unlike the UK and the USA, staff tend to join a company from university and stay with it throughout their career: ‘lifetime employment’ (shushinkoyo). An employee who leaves the company mid-career tends to be viewed as ‘disloyal’ to the corporate family and is regarded with suspicion by other Japanese employers.123 It is not easy for foreign-owned businesses to establish themselves in Japan by acquiring appropriate high calibre male staff by poaching and offering a higher salary; instead, they tend to look to women — a marginalised category in Japanese business society – or expatriates who may not have the established network relationships important to doing business. Japanese attitudes towards work as a lifetime commitment to a company are slowly starting to change;124 new young graduates or managers who have worked overseas are more predisposed to forgo employment security and join a foreign company with a known name and reputation,’125 particularly if slowing growth within the Japanese company – where promotion is traditionally by seniority – limits career prospects.126

Recruitment and selection

Recruitment through newspaper and journal advertisements is popular in many countries, as is ‘word of mouth’ recruitment – particularly in Greece and Ireland — which UK companies might regard askance for equal opportunities reasons. In Korea, there is a tendency for recruitment to favour people from the same geographic area (ji-yun) or university (hahkyun) as the manager;127 because employee loyalty tends to be to the individual manager rather than the company, a Korean manager who changes jobs may bring staff with him.128

In a UK or USA domestic context, gender is an irrelevant issue in selection. However, in some parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East women are not properly accepted — if at all — in senior roles in a business context. The organisation must take this into account in selection; whatever the domestic stance on gender, the societal values of other countries cannot be confronted head on if the objection to senior businesswomen is rooted in deeply held and widespread religious beliefs. However, some countries are merely unaccustomed to women in senior roles, rather than strongly against accepting them. In Japan, foreign highly skilled businesswomen, particularly if they speak the language, may be regarded as ‘honorary men’ and thus accepted.

France places great reliance on the handwritten application letter which can be analysed by a graphologist, whereas graphology, used by 97 per cent of French organisations,129 is given scant regard because of poor validity by most UK businesses, only 3 per cent of whom admit to using it. Skills shortages, HR activities contracted out to agencies, and increasing pressure on budgets have encouraged French companies to use astrology and numerology, palmistry, phrenology and haemotology130 to assess applicants’ characters. Some countries, such as Denmark, use CVs rather than application forms.131 The emphasis placed on aspects of the candidate’s career and life history differs between countries: in the UK evidence of social and leadership skills is highly regarded; in other countries, such as Germany and France, much more emphasis is placed upon qualifications and grades.

Interviews are widely used but the types of questions regarded as ‘fair’, ‘suitable’ and ‘relevant’ vary between countries. The USA and EU equal opportunities approaches preclude questions about marriage intentions and children, which would be perfectly acceptable, if not expected, elsewhere. In practice, in some EU countries, such as Greece132 and Italy: ‘more searching questions may be put and expected than is normal in the UK, equal opportunity legislation notwithstanding’.133

Candidate behaviour at interview also varies and managers should interpret it in the light of the cultural norms of the applicant’s country. A US candidate is likely to broadcast and play up his/her personal achievements and promise miracles,134 but in other cultures such behaviour may seem like boasting or ignoring the impact of a team’s effort.

Psychological tests and questionnaires, beloved selection tools in many American organisations, meet with limited acceptability elsewhere in the world. Parts of strongly Roman Catholic southern Europe, such as Spain, disapprove of them although trade unions prefer them as a means of limiting nepotism.135 In France, psychometric questionnaires have lost credibility and are less used than hitherto.136 Any psychological instrument to be used outside the country and category of people on which it was norm tested needs very careful examination as to cultural validity and culturally sensitive language translation. Psychological instrument compilers Saville and Holdsworth have produced an eleven language ‘International Testing System’ specifically to meet this need.

A global company, seeking the best talent regardless of national origin, could establish an international assessment centre to identify employees, from a range of countries, with potential senior managerial talent. From their experiences of running a European assessment centre, BP found that participants’ norm reactions vary according to nationality, and culturally determined appropriate behaviour needs careful consideration and interpretation.

Anglo-Saxon assessment centre approaches predicated on ‘everyone has equal rights’ would not work successfully in cultures in which this belief was not implicit.137 The American, UK and northern European analytical, numerical and judgemental emphasis in assessment centres tends to be resisted in Latin countries and France which prefer a more ‘human’ and developmental emphasis.138 Work situation observation exercises would not be acceptable in Arab countries where it is seen as an affront to dignity to be watched whilst working.139

The qualities of an ‘effective manager’ need redefinition according to the culture in which the person will be operating. The implicit meanings behind words such as ‘leadership’ differ between countries, making problematic both the design of exercises to test such a quality and the interpretation of outcomes. While organisation leaders in all countries need to attend to both task achievement and relationship management:

how this is to be accomplished in each setting will be dependent upon the meanings given to particular leadership acts in that setting. A supervisor who frequently checks up that work is done correctly may be seen as a kind father in one setting, as task centred in another setting, officious and mistrustful in a third. The meaning of acts is given by the cultural context within which they occur. In collective cultures, the attribution of meaning is likely to be more concensually shared than would be the case in more individualist societies.140

Training and development

Recruitment sources for new managers and their education and training differ between countries. Evans, Lank and Farquhar (1989)141 identified four distinctive management development approaches, heuristics to national practices which none the less vary considerably within, as well as between, countries: the ‘Japanese’, the ‘Latin’, the ‘Germanic’, the ‘Anglo-Dutch’.

According to a 1992 survey of top managers across Europe,142 common characteristics of management in Europe, compared to Japan and the USA, are:

• orientation towards people as individuals;

• internal negotiation within the company (not top-down orders US-style or the consensual Japanese-style of decision-making);

• managing international diversity (more tolerance for another country’s culture);

• managing between two extremes – the American and Japanese approaches: short-term profit versus long-term growth; the relationship between the individual and the firm of ‘hire and fire’ versus lifelong commitment; the balance between individualism and collectivism in the workplace.143

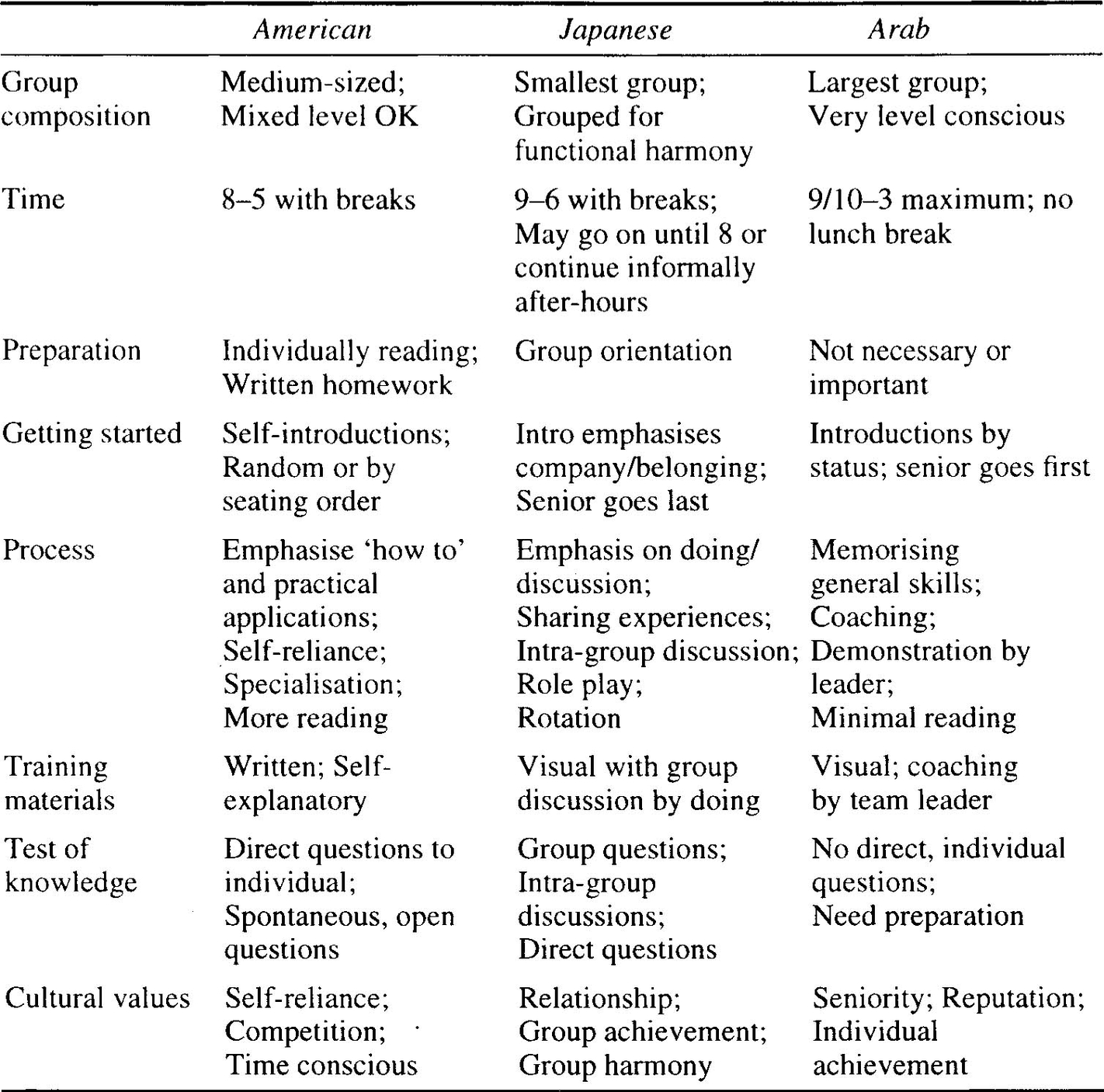

Managers running training sessions for people from different national origins need to be aware that parent company training programmes designed for PCNs, whether managers or other staff, may not transplant without adaptation. Local systems of qualifications, education and training may make them inappropriate; the style of session which worked back home may not be effective, as norms of participation, informality, and views about the status of the teachers and their pronouncements vary. Above, Elashmawi and Harris (1993)144 have identified approaches and dynamics of some ‘typical’ training sessions for different cultures (see Table 13.7).

Table 13.7 Cultural contrasts in training

Source: Elashmawi, Harris, Multicultural management

Employment terms

The nature of the employment contract, the rights and obligations of the parties thereto, and employee and employer expectations of terms and conditions, hiring and firing and employment protections may vary considerably between countries, and may vary within a country for a range of reasons. Employment rights may be affected by whether the employer is a state or private company (PRC), the employee is a core or peripheral worker (Japan), the reasons for the termination (USA, EU countries) and length of service. Workers employed by foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in the PRC are said to have ‘clay rice bowls’, as they are not employed on the basis of lifetime employment – ‘iron rice bowl’ 145 – still prevalent, although now rapidly decreasing, in state-controlled enterprises (SCEs).

In Japan, employment is seen as more of a relationship than a contract and there is a disinclination to register promises in a legalistic manner in a contract document146 as this constitutes ‘alien behaviour which would meet with social disapproval (taningyogi)’.147 Most ‘regular’ staff in Japanese companies never have a contract of employment,148 nor are many of the obligations and expectations of employment explicitly given in the enterprise’s Works Rules.149 It is acceptable to lay off part-time staff or older ‘retirees’ in Japan, but a good company will go to considerable lengths, including accepting underemployment in the enterprise, to avoid making ‘regular’ staff redundant.150 In Korea, during business downturns, layoffs are accepted practice at all organisational levels.151

Performance and reward

Foreign subsidiaries’ financial results are to some extent an outcome of the MNE’s approach to financial management – transfer pricing, exchange rates, accounting conventions – and global competition. Host country import levies, restrictions on profit repatriation and fiscal stance can distort the value of the subsidiary’s performance to the parent.152 Subsidiary financial results should be used with care when appraising the chief executive of a foreign subsidiary; instead, performance could be measured using ‘parallel accounts’ adjusted for the effect of the distorting variables, or against long-range goals such as health and safety improvements, market share and effect on the environment.153 Each main Cable and Wireless business unit reports on: customer and employee satisfaction, business performance, productivity and growth.154 Expatriates who are not chief executives are most appropriately assessed against criteria for their specialism and cross-cultural skills.

The best approach for appraising HCNs in foreign subsidiaries is to use host country appraisal mechanisms, but if a global approach is required, it is preferable to specify what must be achieved, such as:

• coaching;

• appraisal based upon accountability (group or individual);

• development discussions;

• human resource plans;

• instant feedback.

This does not specify how this should be done. This allows for local cultural variation.155 Appraisal outcomes need to be evaluated in the light of cultural norms about praise and negative remarks. In Korea, where job attitude and special ability are appraised as well as performance, many managers are reluctant to give too negative an evaluation of their staff as this will undermine the much valued harmonious relationship between boss and staff; instead, staff are evaluated on a ‘that’s good enough’ (koenchanayo) basis which implies tolerance and sincere appreciation of another’s efforts.156

Values on distributive justice norms vary between countries; the philosophy underpinning reward management might be: equity, equality or needs. Equity underpins most Western approaches to rewards. It implies pay for competencies — inputs, or outputs — performance outcomes. Job holders perceived to be doing work of analogous worth, are used as pay comparators. The implication is that as inputs or outputs increase, rewards should be increased for the situation to be ‘equitable’. Inequity is stressful, and an employee is motivated to reduce it by one means or another.

Equality approaches, where everyone gets the same – for example when a bonus of the same absolute amount is distributed to all staff – are emphasised more in some countries in Southeast Asia. The issue here can become delineating who is part of the ‘in group’ and thus who is deserving of the equal reward. In practice, even collectivist Chinese cultures tend towards an individualistic Western equity-based pay approach, the wealthier they become: individual performance and skill can dramatically affect pay in Hong Kong and Singapore.157

Needs-based rewards are not just found in socialist states. Expatriates are usually housed and given return home flights in accord with their needs as single or family persons.

The perceived relative value of money and other benefits varies between countries, not just because of the local fiscal policy but also because of cultural values. In France, subsidised transport, company restaurant lunches or luncheon vouchers are common and the Philippine worker values a measure of rice with better quality rice being given to skilled workers.158 In the PRC, staff are paid in cash whatever their level, as the banking system is underdeveloped.

In the USA senior executive pay could be 100 times that of the average worker; in European countries a multiple of 12 to 15 is more common and a large disparity is seen as socially reprehensible.159 In Japan too, the gap between top managers’ pay and that of the average workers is small, relative to the USA, as a result of the Japanese emphasis on egalitarianism and togetherness.160

Age and seniority as well as group and company performance determine pay in Japan, but there is little differential for individual performance or exceptional skills.161 Bonus payments, made during the two traditional gift giving seasons in Japan, can comprise as much as a third of total annual pay for an employee and large companies make them to all staff.162

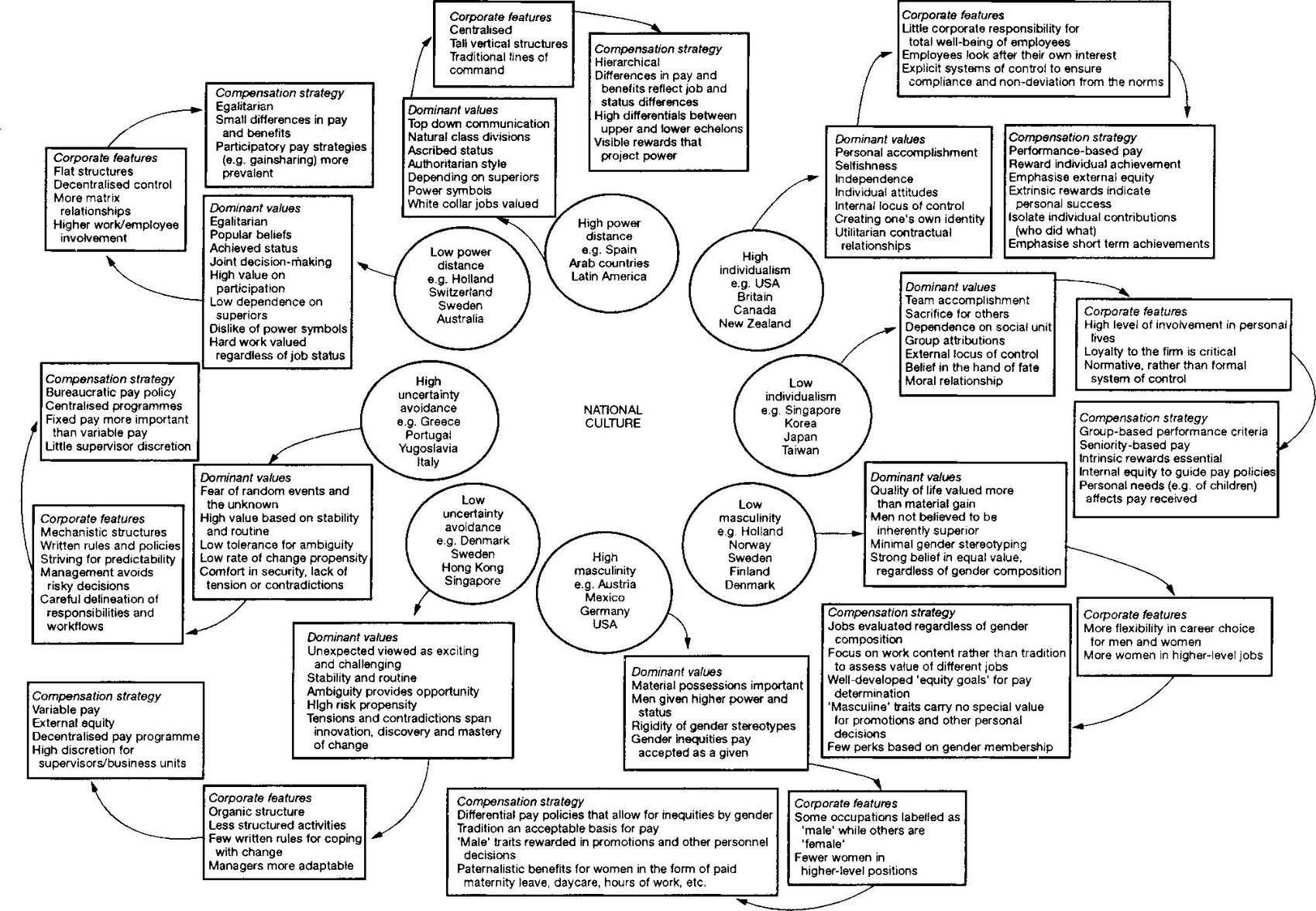

Gomez-Mejia and Welbourne (1991)163 using Hofstede’s164 national culture findings, derived a theoretical framework of appropriate reward strategies from the dominant values and organisational characteristics associated with the poles of each of Hofstede’s four dimensions (see Figure 13.7).

Figure 13.7 National cultures, organisational characteristics and compensation strategies

Source: Gomez-Mejià, Welbourne, in Sparrow and Miltrop, European HRM in transition

They point out that:

• Each of the four dimensions and the country’s placing on them will influence the extent to which the rewards strategy outlined is in fact appropriate.

• Poor reward strategy implementation and work design issues are as likely as cultural differences to create difficulties with rewards.

• Global organisations with their own strong cultures may be able to use these as a philosophical basis for rewards, irrespective of local cultural norms.165

13.8 Expatriate rewards

The philosophy usually stated as underpinning expatriate rewards is to keep the expatriate ‘whole’, i.e. no worse or better off as a result of expatriation. However, expatriates often expect to be better off as a result, and companies may need to ensure that they are if they are to tempt an employee to work abroad.