3 Selection methods

3.1 Introduction

The process of selection is perhaps the most important of activities in managing human resources. To say an organisation is only as good as the people in it is a cliché, but like most clichés it is substantially true. Choosing the right person for the job enhances organisation efficiency by ensuring the job is well done. More than this, effective selection can help enable ‘promotion from within’ and make management development policies practical realities. In this latter context selection must be seen in the light of the company’s manpower plan which follows from its business plan.

The importance of good selection is highlighted by the effects of making wrong choices, for example:

• increased recruitment costs from having to readvertise a vacancy and time spent screening application forms, writing letters, setting up initial interviews and other assessment methods;

• the damaging effect on team morale — caused by staff instability — can be aggravated by diminishing respect for a management which has demonstrably showed lack of judgement through its selection methods;

• while the vacancy remains or the wrong person is in the job, the job is not being properly done, creating an opportunity cost to the organisation which can be substantial.

The chances of picking the right person at the outset are greatly influenced by the choice of assessment available to management and the degree of accuracy employed to assess knowledge, competencies and personality traits.

Selection is essentially a two-way process where the employing organisation seeks to assess the suitability of applicants in terms of what it requires. Applicants make similar judgements on their own criteria, i.e. what they want from the job and from the organisation.

Selection is very much a process concerned with making a prediction from data obtained about candidates from methods of assessment such as cognitive tests and personality measures about how they will perform once in the job. From the individual’s point of view the process is similar except that the prediction is based upon the perceived demands of the job, e.g. effort, abilities, pressures, etc. and the self-assessed abilities and motivations of any individual.

The assessment applicants make has been described as their self-efficacy;1 this is the confidence they have in their own abilities to do the job successfully. Applicants are unlikely to take a job unless they feel they can do it. Similarly, a potential employer would only offer a job if it was felt that the candidate would be successful in it. Unfortunately both individuals and organisations can make predictions often based on insufficient evidence or data and sometimes these predictions are wrong — resulting in further recruitment costs; the opportunity costs of a vacancy not filled; the (often negative) impact on team morale and the effect on the individual.

How well methods of assessment, including self-efficacy, actually work depends on their predictive validity and the concept of validity as a whole which has a fundamental impact on the efficiency of the selection process. Since the purpose of assessment is to discriminate between job applicants — on legal grounds — in terms of their suitability for the job, the assessment methods used are all forms of tests. The term ‘tests’ is used to refer to the generality of assessment methods.

3.2 Validity

The validity of an assessment method, e.g. psychometric tests, interview, work sample, assessment centre ratings, concerns what the test measures and how well it does so. The word ‘valid’ is meaningless in the abstract, i.e. without specific reference to the particular use for which the test is being considered. All procedures for determining validity are concerned with performance on the test and other independently observable or specified behaviours. There are four types of validity, as follows:

1. content-related validity

2. criterion-related validity

3. construct-related validity

4. face validity.

Content-related validity

If a test samples and measures the knowledge, skills or behaviours required to perform the job successfully then the test has content validity. Content validity is usually determined by a detailed job analysis, with each duty or task described — together with the associated knowledge and skills required to perform it. The most important and the most frequent activities should be identified so that the job analysis provides an accurate picture of the whole and also provides a weighting for the skills and knowledge required when compiling the Person Specification.

There should be a direct relationship between job content and test item. For example, when recruiting secretaries for whom spelling might be an important ability, a preferred method of testing this would be to dictate a passage involving words typically used in the job and then checking for errors of spelling, rather than use a multiple choice test with the instruction to ‘Underline the correctly spelled word’. Content validity can also play an important role in deciding issues of unfair discrimination.

Criterion-related validity

This kind of validity is a measure of the relationship between performance on a test and performance on a criterion or set of job performance criteria – these might be competencies, performance ratings or objective measures.

This type of validity is in many ways the most important to successful selection given that the selection process is essentially predictive. There are two types of criterion-related validity – concurrent validity and predictive validity – and these are now explained.

Concurrent validity: The concurrent validity of a test is established by selecting a large sample (about 100) of existing job holders and asking them to complete the test. These job holders are then assessed on their work performance — the assessment usually being done by immediate managers, who do not have prior knowledge of individual test results. Performance criteria might be 5- or 7-point rating scales or sometimes job holders are grouped into high, medium and low performers. Scores on the test are then matched against performance and a test is said to have concurrent validity if there is a statistically significant relationship between test scores and performance.

Predictive validity: Predictive validity refers to the extent to which scores on a test actually predict performance criteria. For example, to establish the predictive validity of a test of numerical reasoning ability job applicants would take the test but the results would not be used to influence the hiring decision. Instead, applicants would be selected by whatever existing assessment methods currently apply. At a later stage, perhaps after 6 months or so of being in employment, performance criteria ratings would be obtained and matched against the scores the former applicants (now employees) obtained on the numerical reasoning test. If there is a close relationship between test score and job performance then the test can be said to have significant predictive validity.

Concurrent vs predictive validity: Since selection involves prediction, it follows that organisations would carry out a predictive validity study before introducing any new methods of assessment. There is no doubt that such studies provide the best evidence for adopting or rejecting an assessment technique. In practice, however, they are rarely used, for a number of reasons.

First, the costs involved; it might be that in the case quoted above the numerical reasoning test was a poor predictor of performance. While it could be argued that this is still important knowledge it is not always easy to convince organisations of this. A further problem is sample size: for a validation study to have any statistical credibility this should be around the 100 mark. So with a predictive validity study we are looking for 100 applicants for the same or similar jobs who are subsequently hired. Except in ‘start up’ situations, it may take all but the very largest employers many years to reach a figure of 100 new starters, by which time many of the early starters may have left, performance criteria may be changed, the job may have become more/less difficult due to the economic environment, technology may have changed the job, etc. Such difficulties make predictive validity studies a comparatively rare event except in the largest and most stable organisations.

Concurrent validity studies, on the other hand, are somewhat easier to conduct. The problem of sample size is still an issue, tending to make it difficult for small to medium-sized firms to carry them out. It is a relatively large organisation which will employ 100 people all engaged in the same or broadly similar jobs. However, given sufficient people, the time factor is not an issue. Other factors, however, which need to be considered, perhaps principally the need to allay the employees’ fears that they are completing tests for the sole purpose of research into a new assessment method and not as criteria for ‘selection’ for redundancy or some other unwelcome change.

Several factors limit the extent to which concurrent validity can be used as an indicator of predictive validity. First, if a test has content validity, i.e. it measures ability needed in the job, then experience in the job may improve performance on the test, producing average test scores less likely to be attained by job applicants — thus potentially good employees may be wrongly rejected. Second, the conditions in which job seekers as against existing staff compete may also make a difference to comparable results. For example, a test involving problem-solving may be done less well by people with higher anxiety levels (job seekers) than by existing staff for whom the outcome is not pass or fail. Nevertheless, concurrent validity studies are easier to undertake than predictive studies and many organisations do carry them out and use the results as best evidence about validity prior to ‘going live’, using a new assessment method as a selection tool.

The criteria problem

There are some problems associated with defining and measuring performance criteria. Since criterion-related validity is a measure of the relationship between scores or performance on an assessment method and how well people actually do the job — the performance criteria — it follows that if it is not possible to obtain criteria which permit accurate evaluation between people and which reflect the real purpose of the job, then the results of validation studies are devalued. Job criterion measures fall broadly into two categories:

1. objective criteria

2. subjective criteria.

Objective criteria: Objective criteria measures generally refer to performance outputs or aspects of the job which can be objectively measured. Some examples are the volume, quantity or calls to order ratio for sales people; the number of times the telephone rings before it is answered as a measure of the efficiency of a switchboard operator; delivering a project on time, within budget and up to quality might be criterion measures for evaluating the performance of a project manager.

The problem of using such measures as indicators of job success is that there is a tendency to select those aspects of a job more easily measurable but not necessarily of fundamental importance to the core of a job. For example, with the telephone operator, the manner in which a telephone is answered might be more important to the image of an organisation than the fact that the telephone was answered after 3-4 rings. Of course, a best position is where the telephone is answered promptly and in the right manner, but where measurable criteria are in place, concentration tends to be placed on them sometimes to the detriment of ‘softer’ but equally important criteria.

A further issue is the extent to which ‘outside’ factors, i.e. outside the control of employees, affect performance. For example, decreases in labour turnover may reflect high unemployment and lack of job opportunities elsewhere rather than the efficiency of management policy on employee retention. In the same way, changes in exchange rates may have substantial effects on the volume of export sales but nothing whatsoever to do with the quality or abilities of export sales people, making individual assessment on sales criteria very difficult. Such situations in themselves render so-called objective assessment open to subjective influence. An assessor might attribute improvements in export sales in some individual cases to changes in exchange rates, yet in other cases to improvements in selling ability — in the former attributing changes to the situation and in the latter making attributions to the person. Ways of establishing more reliable objective criteria are discussed later.

Subjective criteria: Perhaps the most frequently used example of subjective criteria is based often on competencies and/or overall performance and invariably using a 5- or 7-point rating scale. It is not the intention here to review or discuss the somewhat exhaustive findings on the bias inconsistency and error associated with such ratings. Perhaps the best-known of these errors is the ‘halo’ effect, defined by Saal et al. (1980)2 as a ‘rater’s failure to discriminate between conceptually and potentially independent aspects of the ratee’s behaviour’ (in the case of performance criteria, raters may not be able to make distinct judgements between a ratee’s position with regard to separate competencies), thus, for example, the individual rated, say, 5 on ‘managing people’ will be likely to be judged similarly on ‘problem solving’ or ‘planning and organisation’. A further error comes from leniency or severity meaning a tendency to assign a higher or lower rating than performance warrants.3 Finally there is a tendency for raters to rate around the mid-point of the scale — ignoring the outer limits — an error of central tendency leading to restriction of range.

Rater characteristics also affect ratings; Herriot (1984)4 reports sex and occupation interaction in such a way that female workers are rated less favourably when in traditional masculine occupations. Ethnic origin and gender also interact: Herriot also cites incidences where the more white men there were as assessors in an assessment centre, the lower black women were rated.

Clearly all inadequacies in being able accurately to measure the efficiency of one employee against another can have serious effects on the results of any criterion validity study and, more importantly, can make selection more like a lottery than a systematic, logical process.

Construct-related validity

The construct-related validity of a test is the extent to which the test is measuring some theoretical ability, construct or trait. As an example, take a personality trait such as extroversion and assume the task is to construct a set of interview questions which will give an accurate measure of the trait. The construct validity of the interview can be established by having all the interviewees complete a personality test which measures ‘extroversion’. If interviewees are defined as extroverts via the interview and as extroverts via the personality measure then the interview can be said to have construct validity. Establishing construct validity may involve quite extensive studies and a large number of people to achieve statistical respectability.

Face validity

Finally, an assessment method will have face validity if questions or test items are seen by candidates to be reflective of the nature of the job. Thus in devising a test for would-be accountants, face validity would be enhanced if terms used in the accounting profession featured in the test, e.g. profit, depreciation, costs, budget, etc. While there is no evidence that face validity affects candidates’ performance, the use of job-relevant items and questions will serve to give applicants more information about the job, thus facilitating the self-selection process mentioned above.

3.3 Correlation

Construct- and criterion-related validity are assessed and expressed by a correlation coefficient while content and face validity are assessed by more qualitative means. The correlation coefficient (denoted by ‘r’) indicates the strength of the relationship between two (or more) variables and takes on values ranging from −1.0 (perfect negative relationship) to 0 (no relationship), and to +1.0 (perfect positive relationship). This is linear correlation which assumes a straight line relationship between the variables. Some examples may help to clarify this, as shown by Figures 3.1-3.3.

Figure 3.1 Perfect correlation

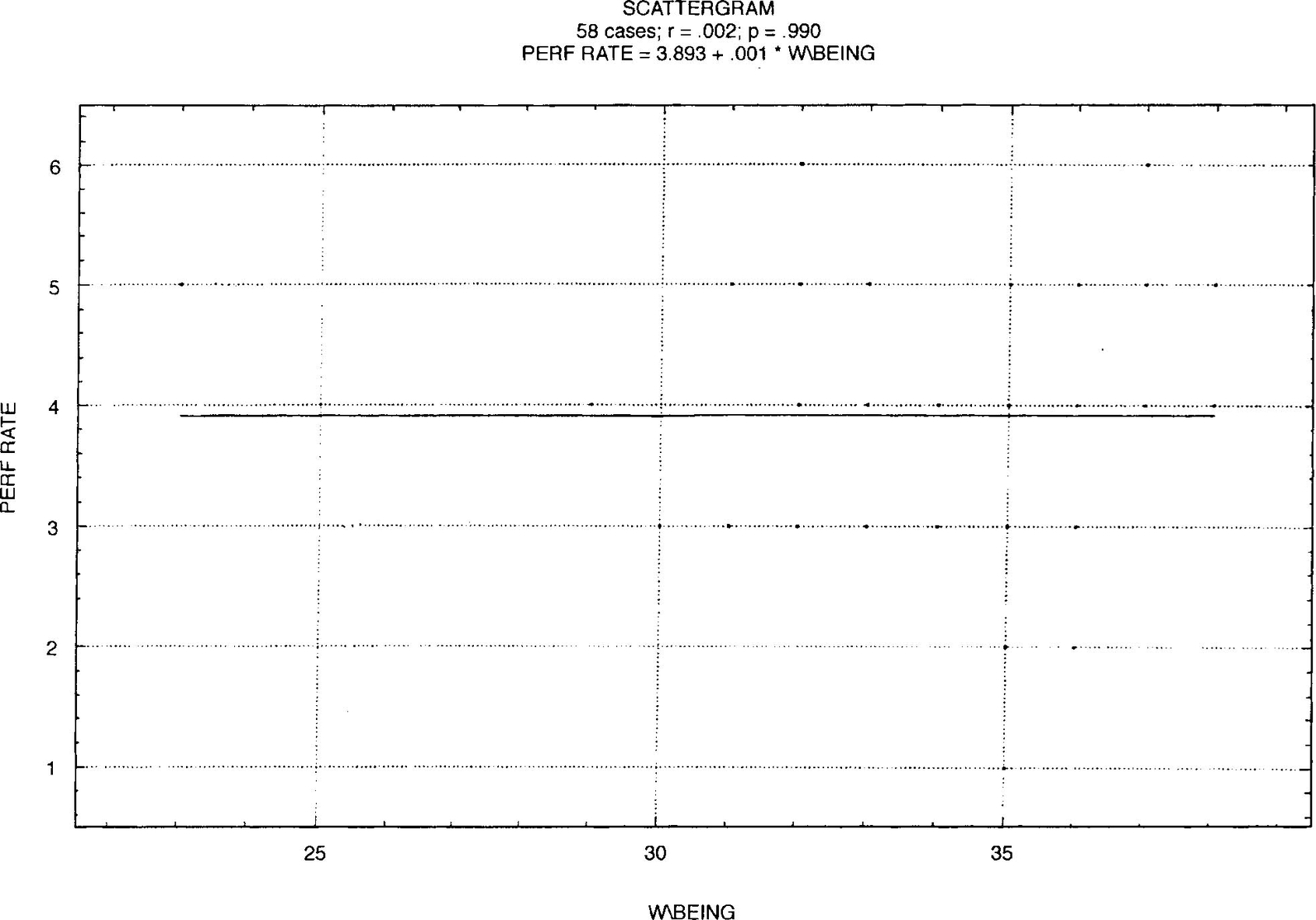

Figure 3.2 Zero correlation

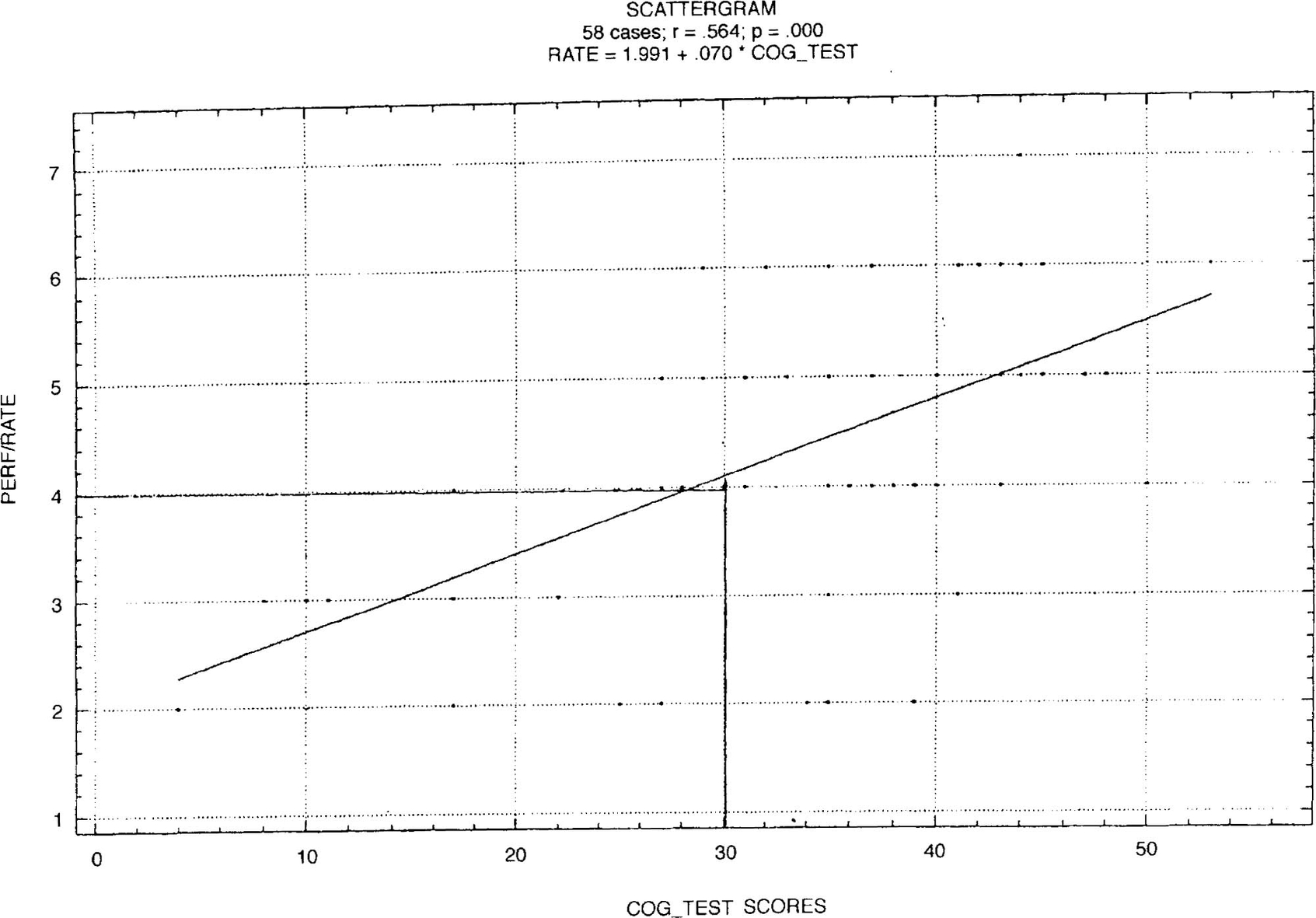

Figure 3.3 Best fit correlation

Changes in room temperature and changes in the mercury level of a thermometer would represent a correlation of +1.0 as temperature increases and the mercury level moves up the scale. Zero correlation might be indicated by changes in body temperature and times of the day — assuming the body remains still and is healthy — the body will maintain a constant temperature regardless of time. A negative correlation occurs when decreases in one variable are associated with increases in another; for example, number of days training in interview techniques and volume of staff turnover within the first three months of employment, the implication being that more effective assessment leads to lower staff turnover.

The coefficient of correlation under certain measurement conditions represents the slope of a straight line with a value of r = 1.0 being perfect correlation shown by a 45° line going through the origin of the graph. A line with a slope of 0 would be horizontal, indicating a correlation coefficient of 0. Correlation analysis provides a line which provides the best mathematical fit to the data — even though as can be seen in Figure 3.2 the fit is still poor.

Figure 3.1 gives an example of perfect correlation, r = 1.0. All the points representing room temperature and levels of mercury lie on the straight line. Note that where r = 1.0 there is perfect prediction, thus if room temperature moves to 10° from 15° then the mercury level will do likewise. Regrettably, correlation of this magnitude is never encountered in the selection field.

Figure 3.2 represents a zero correlation between performance ratings for 58 middle managers in a wholesale newspaper firm and their scores on the personality trait of ‘sense of well-being’. Note the straight line is horizontal. It can be seen that the dots where the variables have been plotted against each other are almost randomly distributed and bear no obvious relationship to the horizontal line. In terms of prediction the graph is of no use; changes in performance ratings have no bearing on difference in ‘personal well-being’.

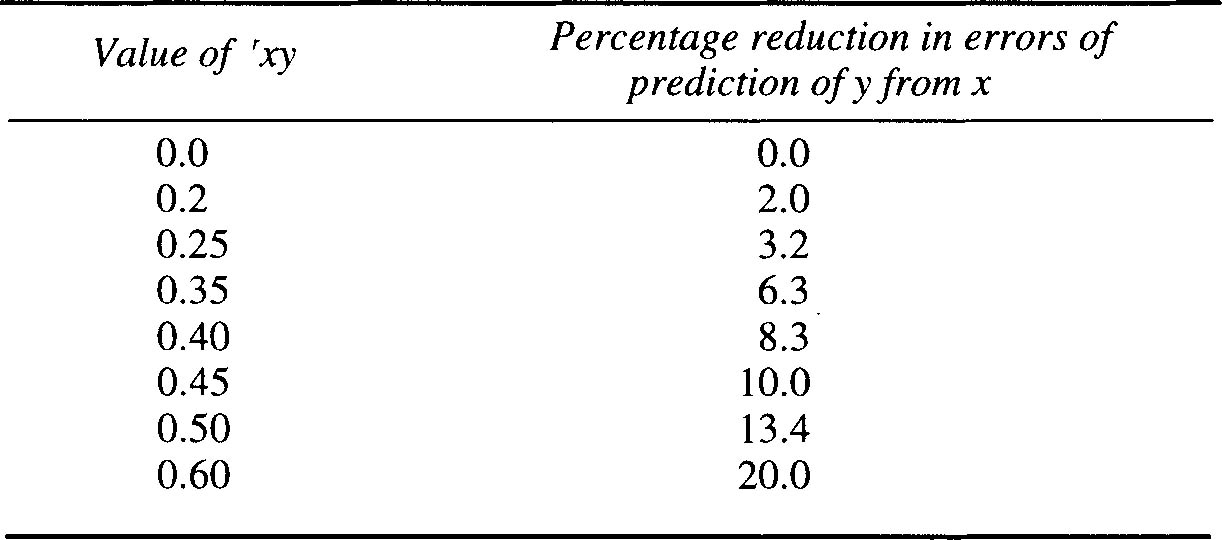

Figure 3.3 represents a scattergram showing the relationship between scores on a test of verbal and numerical ability and overall performance ratings for 58 managers employed in a leading grocery organisation. Note the scatter points are distributed around the straight line rather than on it, emphasising that the line is one of ‘best fit’ with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.564, which represents high criterion-related validity. Even so, it was decided that the cut-off point on test score is 30, with a corresponding performance rating of 4. Thus anyone scoring less than 30 would be rejected. (All the points in the area less than 30 but not more than 4 represent rejections — in spite of satisfactory ratings.) These scores are termed ‘false negatives’. Similarly, there would have been a number of ‘false positives’ shown by the points in the area exceeding 30, but less than 4. These people would have been recruited only to have turned out unsuccessful, given a criterion of minimum performance rating of 4. Fortunately, in the majority of cases the predictions would have been accurate. From such examples it can be seen that the greater the value of r, the greater the degree of accuracy in prediction, as Table 3.1 shows.

Table 3.1 The correlation coefficient and forecasting accuracy

3.4 Measuring validity

Construct- and criterion-related validities are measured by a correlation coefficient. In the case of criterion-related validity the variables are scored on the assessment method and on some criterion measures. The resulting correlation is known as a validity coefficient. With construct-related validity, the correlation may be between scores on two similar tests, e.g. if scores on two tests of general cognitive ability correlate with a validity coefficient of r = 0.8, then it can reasonably be assumed that both tests are measuring the same type of ability.

Construct-related validity may also be assessed using factor analytical statistical techniques which are beyond the scope and purpose of this book. Content-related validity is assessed through qualitative means, using observation and interpretation. For example, comparing job analysis and person specifications with test questions will provide evidence that the assessment method is designed to measure the competencies, knowledge, etc. required to do the job. A similar situation occurs with face validity.

3.5 Reliability

Reliability is a key concept used in the evaluation of methods of assessment. It is defined as ‘the consistency of scores obtained by the same person when re-examined with the same test on different occasions or different sets of equivalent items (questions) or under other variable examining conditions’.5

Consistency or stability is another necessary condition for test validity. A test is of no value if someone, for example, is classified as an extrovert on first being tested but emerges as an introvert if the same personality test is completed a week later. Any criterion-related validity study using such data would be seriously flawed. Perhaps more graphically, if a rule measures a piece of cloth as 1 metre on one occasion but as 1.1 metres on another, then the ruler is of very limited use as a measure — the same principle applies with tests.

Measuring reliability

The most widely used measure is known as test-retest reliability. Here the same people complete the same test on two occasions, the two sets of scores are then correlated and the resulting coefficient is known as a ‘reliability coefficient’. The time interval between tests has a bearing on the value of the reliability coefficient — the longer the interval, the lower the coefficient.

Another method of assessing reliability and consistency is using parallel or alternate forms of test. The same people can be tested on one form of the test and then tested on an equivalent form. The resulting correlation of the two sets of scores is the reliability coefficient. The time interval between tests has a bearing on the reliability coefficient and as with test-retest reliability this should be stated when reliability coefficients are quoted.

Split-half reliability

Another form of reliability is internal consistency, also known as split-half reliability. Here a single test is divided into two halves, e.g. a test of 100 questions would be split into the equivalent of 2 tests of 50 items each. The scores from each half would then be correlated and a coefficient of reliability obtained. There is no time element involved so stability is not assessed. The reliability coefficient is more a measure of the degree to which the test is measuring the same characteristic or ability — consistency, in fact. Tests are generally split on an odd/even question basis.

Before leaving reliability, it is worth pointing out that reliability tends to increase with the length of a test.

3.6 Improving criterion-related validity

Applying meta-analytical techniques (a process whereby the results of many separate studies can be combined), Schmidt, Hunter and Urry (1976)6 demonstrated that the validity of tests of cognitive abilities, verbal, numerical and reasoning aptitudes can be widely generalised across occupations and job functions, suggesting that jobs in advanced technological societies require a common core of cognitive abilities to perform them successfully and that these skills are predictive of performance in different fields of activities.7

The results of this research suggest that tests of cognitive abilities can be successfully introduced as an aid to selection for many kinds of jobs, in many occupations. It is vital to ensure any such tests have content and predictive validity since poor evidence to support this can lead to breaches of equal opportunity legislation.8

With regard to the criterion-related validity of personality measures, it has been shown that validity is significantly increased where a logical link can be established between a personality trait and a specific job activity, e.g. conscientiousness and planning ability. Validity coefficients as high as 0.3 have been reported in such cases.

The accuracy of self-efficacy expectations is likely to be improved where there is a clear understanding of what the job entails, the particular difficulties, most frequent and important activities, not forgetting cultural aspects of the organisation. This kind of information can be communicated via initial recruitment advertisements, job descriptions, interviews and most importantly by allowing job applicants to speak to existing job incumbents, at the actual workplace to find out what the job really entails. Such ‘realistic job previews’ apart from fulfilling the purpose of permitting more accurate self-efficacy expectations have also been shown to reduce labour turnover.9

Since estimates of self-efficacy are likely to be overstated (high self-confidence is often a desirable trait), to reduce the effects of this a simple questionnaire can be constructed on key activities of the job as shown below.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 = very little confidence and 10 = absolute confidence please indicate your level of confidence.

| Rate 1-10 | |

| Reducing costs whilst maintaining quality | ——— |

| Improving management development strategies | ——— |

| Reducing labour turnover | ——— |

| Improving the cost per recruit | ——— |

This completed questionnaire can then be used as part of a structured interview with questions such as ‘You are extremely confident about reducing labour turnover — what do you see as the issues involved and what is the basis for your confidence?’ Such questions can produce unique and revealing insights into candidates’ perceptions of the job — which can then be checked against received wisdom and candidates’ self-perceptions and the evidence for them.

3.7 Choosing performance criteria

Job analysis can identify key activities and major responsibilities which are important in deciding the basis on which individual performance is judged. In terms of objective measures, it is advisable to sample criteria over a long rather than short period of time. Lane and Herriot (1990)10 found that the predictive validity of self-efficacy ratings increased, the longer the time period over which changes in gross profit and admissions were measured. Common sense confirms this view, for example, assignment or examination marks taken over all subjects over an entire year will be a more reliable measure of ability than one result only.

Choose measures over which individuals have substantial control, in other words, measures which when changed reflect variations in job holder performance rather than in other external factors over which the job holder has limited, if any, control.

Accuracy of performance ratings can also be improved by ensuring the rater has had relevant contact with the ratee,11 watching the job being done, perhaps. Finally, the rating process can usually be improved with training. Appropriate training could include improving observational skills, strengthening rater knowledge of job requirements and analysis of common rater errors.

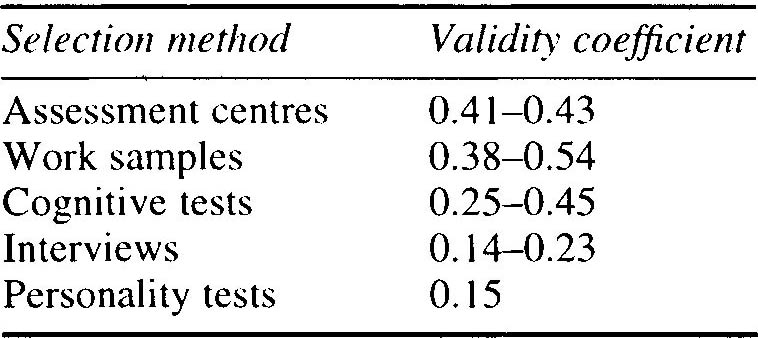

Selection tools

As discussed earlier, the validity of any selection method is clearly dependent on the reliability of the particular test being used and the degree of appropriateness of the purpose for which the test is being used. With this in mind, Robertson and Smith (1989)12 calculated the approximate validity coefficients commonly used as a yardstick with which to compare the validity of the various assessment techniques currently in use to determine selection decisions. These are shown with their respective validity coefficients in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Average validity coefficients for selection methods

Source: Smith and Robertson 1989

3.8 Psychometric tests

Psychological or psychometric tests refer to standardised tests constructed to measure mental abilities or attributes. Within the context of occupational selection, tests of cognitive abilities and personality measures are frequently included in the selection process. The use of psychometrics for selection and development is somewhat patchy in UK organisations. A number of research surveys show variation in the purpose and extent to which tests are being used within organisations.13 Psychometric tests have increasingly gained in popularity in Britain in recent years for staff selection and development purposes with personality tests and cognitive tests now being used for a range of positions from junior clerical to senior managers and in a variety of environments including manufacturing, service industry and managerial environments.14

Cognitive tests

Cognitive tests or ability tests can be split into two major categories: attainment and aptitude tests. Attainment tests are measures of learned or acquired knowledge. Traditional examinations to assess the level of knowledge acquired by students in a specific subject fall into this category. In an occupational setting such measures may be useful in order to establish that the employee has a sufficient grasp of a specific subject to be able to undertake the demands of the job. Professions such as medicine and law require their practitioners to undertake a series of attainment tests in order to gain professional qualifications. Such qualifications assure an employer that a potential employee has the essential knowledge and/or skills to work to a minimum standard of competence.

Aptitude tests concern an individual’s ability to acquire skills or knowledge in the future. They may be designed to measure either general ability levels or a specific aptitude. All such tests are designed to be carried out in a standardised fashion; tests are strictly timed so that all candidates have the same length of time available in which to complete the tests. The environment must be suitable with minimum distractions to candidates in order to ensure that they perform at their optimum level. Test instructions are delivered to all candidates in an identical fashion, and scoring is carried out in an objective manner with the use of pre-coded scoring systems. Many tests can now be scored by computer scanner to calculate performance levels. The advantages of such standardised systems include the fact that all candidates are tested under the same circumstances, asked the same questions and given identical tasks to do. The objectivity of scoring systems eliminates the opportunity for personal biases and interpretation of individual testers to influence the performance rating of the candidate. Scores on these tests are interpreted using norm tables which allow us to compare an individual’s performance against a group of their peers, e.g. fellow school leavers or graduate applicants. Using this system of scoring, one test can thus be suitable for use at a variety of achievement levels. A range of tests is available for different levels of occupations. In particular there is a wide range of verbal and numerical tests, some of which are job-specific and aim to test people using the type of information they are likely to deal with in the job, e.g. technical or sales-oriented.

General ability or general intelligence tests aim to assess a candidate’s intelligence level by examining a cross-section of mental areas including verbal ability, numerical ability, the ability to recognise and interpret shapes, and so on, using pen and paper-based exercises. These tests are used in a variety of situations from educational to occupational settings. In the case of selection, general ability or general intelligence tests are often used where specific job measures are not important or not available and the candidate’s potential to benefit from, e.g., a management training course is more important than their current levels of knowledge in a particular area.

Specific ability tests

Specific ability tests aim to test just one area of an individual’s ability and appropriate tests are chosen according to the specific abilities required to do the job in question. The most common groups of such tests are the following.

Verbal ability tests: These generally aim to test either the level of verbal understanding or the verbal critical reasoning skills of the candidate. They normally consist of either a series of words from which a meaning needs to be decided or else require the candidate to read a passage of information and then answer a series of questions based on the text. These tests do not aim to measure attainment but level of language fluency. In selection they are used for a wide range of jobs — from those which demand that candidates understand basic written literature such as health and safety directions, to senior positions where an aptitude for interpreting detailed information from complex reports is of importance.

Numerical ability tests: These tests examine the numerical strengths of candidates; normally they involve a series of mental arithmetic tasks to be calculated in a short period of time. Numerical critical reasoning tests use graphs or charts from which candidates interpret statistical information and deduce conclusions from the information provided.

Diagrammatic ability tests: These tests usually consist of a series of abstract shapes and diagrams which candidates are required to follow and interpret. They are used in assessing those who are likely to have to follow instructions in diagrammatic format such as electricians or those having to work from engineering or architectural plans.

Spatial ability tests: Candidates are required to visualise and mentally manipulate 2- and 3-dimensional shapes, often being asked to recognise patterns or changes in series of pictures. Such tests are used primarily in selection of technical staff.

Mechanical ability tests: The ability to demonstrate mechanical reasoning aptitude is tested using a series of pictures which require candidates to interpret the meanings of the pictures and the likely outcome of certain mechanical interactions. A basic knowledge of physics may facilitate the interpretation of such diagrams. Performance on these tests may be somewhat influenced by previous experience as well as mechanical aptitude.

Manual dexterity tests: Manual dexterity is usually assessed by setting candidates a physical task requiring them to assemble a number of components in a short period of time. Speed and precision are usually the focus for such tests although many dexterity tests reflect the specific requirements of the job, e.g. a mechanic might be asked to assemble part of a car engine.

Personality questionnaires

Judgements about personality are made on a daily basis as we attempt to understand and mentally categorise the people we come into contact with. We assign certain attributes to individuals on the basis of their physical appearance such as their height, weight and skin colour, and we also associate certain stereotypical characteristics to features such as nationality or regional accents. Most of the assumptions we make about people on first meeting them are based on very little real information, are open to our personal biases and are often quite inaccurate. A more structured attempt to measure scientifically or compare people has been devised in the form of ‘paper and pen’ personality tests which attempt to compare individuals objectively along a number of dimensions.

Personality measures originated in the clinical environment where they were used as diagnostic tools and as measures of mental stability. The Woodworth Personal Data sheet was the first widespread personality measure to be used in an occupational environment. This questionnaire was used in the First World War as a screening device to sift out those individuals mentally unsuited to service in the army. In essence it was a standardised psychiatric interview which could be administered in a self-completion format to many individuals at once.

There are many psychological approaches and theories as to the nature and definition of personality. Apropos selection, the trait and type theories assume a number of stable and enduring dimensions of an individual’s personality which can be measured and assessed to establish suitability for specific job requirements. Personality tests used in an occupational environment are standardised self-completion questionnaires. Typically they present a number of statements about preferred ways of behaving and ask the candidate to indicate whether or not each statement is likely to reflect their behaviour. There are no right or wrong answers to the questions; respondents’ answers are used to build up a profile about their preferred mode of behaviour in a number of circumstances. Examples of the typical items found in personality questionnaires can be seen below:

| True | False | uncited | |

| (i) I enjoy being the centre of attention | □ | □ | □ |

| (ii) I like solving technical problems | □ | □ | □ |

| (iii) I prefer to work on my own than with a group | □ | □ | □ |

The traits being measured by personality inventories vary somewhat in both definition and number, though five core traits known as ‘the Big Five’ are generally found in most of the commonly used personality questionnaires, these include: extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and intellect. The 16PF, one of the most widely used personality tests in Britain, was designed by Cattell to measure 16 personality factors or traits. Scores are assembled to produce a profile on the 16 scales including traits such as reserved-outgoing, tough-minded-sensitive, practical-imaginative and submissive-dominant. Norms, or average test scores, are available for a variety of professions including accounting, engineering and chemists. Other tests such as the Occupational Personality Questionnaire (OPQ) — developed specifically for the UK selection market — measure a number of traits in three broad dimensions: relationships with people; thinking style and feelings and emotions. Other versions of the OPQ have been designed to assess job-specific characteristics such as those traits identified as relevant to a sales job or customer service positions. Questionnaires can be administered either in the traditional pen and paper format or on computer. Scores from the OPQ can either be interpreted by a qualified administrator or can be fed into a computer software expert system which produces a personality profile and detailed report.

Personality tests give an insight into the way in which individuals perceive themselves. A number of obvious problems such as candidates’ desire to shape their answers according to the requirements necessary to gain employment are associated with the use of personality questionnaires. Research has shown their predictive validity to be quite low compared with other psychometric tests; however, when used in conjunction with other selection tools such as cognitive tests, and an exploratory feedback interview (from an appropriately qualified individual), the personality profile can provide a good starting-point for further discussion. It may be very useful in flagging up issues to be addressed in interview which might not otherwise have been discussed.

3.9 Other kinds of test

Work samples

The only certain way of knowing how an individual will perform in a job is to employ them. Given the impracticality of employing all applicants, a realistic alternative is to allow candidates to demonstrate their relevant skills, knowledge or abilities by carrying out a sample of the work. Occupational fields such as advertising, art or architecture have long required applicants to show portfolios or samples of their work as part of the screening process. Work sample tests may be assessments of a practical skill such as a word processing test to assess speed and accuracy for an office post, or a wiring test for an electrician.

In-tray/in-basket exercises

For jobs which are less easily measured such as managerial posts, ‘in-tray’ or ‘in-basket’ tests are commonly used to assess candidates’ ability to cope with typical contents of a manager’s daily work. Such tests require candidates to demonstrate abilities relevant to the particular job such as prioritisation of tasks, critical analysis of reports and written communication ability. The advantage of these tests is that they can be designed to reflect the requirements of the job very closely and this will increase the content and predictive validity of the tool. The materials used in this kind of test normally reflect the nature of the materials a post holder would be expected to deal with daily, e.g. a human resources manager might have to consider problems including selection issues, staff shortages and a formal disciplinary process, while a purchasing manager might have to deal with balancing budgets, stock control issues and purchasing decisions.

Trainability tests

Some positions are not suited to work samples, for instance apprenticeship jobs where it is expected that the successful candidate will acquire the necessary skills ‘on the job’. Technical apprentices are typically trained by a combination of structured training and working with an experienced job holder. In such cases the ability to learn quickly and an aptitude for the relevant skills are the most important determinants of success in the job. Trainability tests typically involve a ‘mock’ training session similar to the type the job holder would receive in the post. After a standardised training session where all applicants receive the same information and tools, a task, e.g. wiring a light, is set, and candidates are assessed on their performance in a number of criteria such as accuracy, speed, tidiness of workmanship, correct use of materials, etc.

3.10 Assessment centres

The selection methods above describe individual selection tools, however, it is widely recognised that multiple assessment methods are more reliable than any single method alone. The assessment centre is a technique which employs a number of assessment tools in an attempt to gather a wide spectrum of knowledge about candidates and achieve more valid selection decisions. Assessment centres were first used in the 1930s by the German Army and were later adopted by the American and British Armies who still use them to select entrants to the military. The first widespread use of assessment centres for graduate recruitment was by AT&T, the American telecommunications company, in the 1950s. Since then assessment centres have gained in popularity for both selection and development purposes and at the end of the 1980s it was estimated that about a third of large organisations in Britain were using assessment centres for selection purposes.15

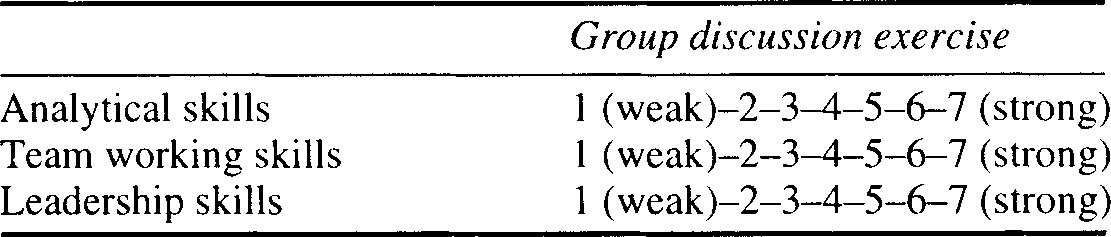

The exercises included in the assessment centre process depend on the nature of the job vacancy. Typically they include the use of psychometric tests, group exercises, presentations, written tasks, ‘in-tray’ or ‘in-basket’ tests and work samples. Candidates’ performance on the various tests and exercises is observed by several raters (normally including relevant line managers as well as HR staff). To increase inter-rater reliability and the overall effectiveness of the assessment centre process, assessment criteria need to be clearly defined and observers trained in the use of the rating scales. An example of the type of scales commonly used in this process can be seen in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Example of rating scales used by observers in assessment centre process

Studies examining the comparable validity of assessment methods rate assessment centres as one of the strongest methods of predicting the performance of a candidate, but they are time-consuming to organise and run as well as being a very costly method of selection. Consequently, the use of assessment centres is largely restricted to graduate and senior management positions.

3.11 The interview

The most commonly used method to select employees is still the interview; very few people in the UK are hired without having at least one face-to-face interview with their employers and many organisations still use the interview as their only tool of assessment. The traditional interview method has been given poor reviews as a way of predicting the best person for a job. A number of research studies examining the validity of the selection interview have found it to be considerably weaker than alternative methods such as cognitive tests or assessment centres.16 The interview as it is normally carried out is unreliable as an assessment method. The information obtained about candidates is often inconsistent and interviewers frequently rate the same candidates quite differently (poor inter-rater reliability). Other factors contributing to the interview’s poor predictive validity include the fact that in structured interviews, material is not consistently covered and the degree or depth of information obtained may depend both on the interpersonal rapport between interviewers and candidates and on the level of nervousness of the interviewee. Other factors to be considered are the likelihood that interviewers will form their impressions of the candidate in the first few minutes of their meeting rather than over the full course of the interview, coupled with the fact that less favourable information tends to have more impact on interviewers than favourable information.17 Despite this, however, few people would be prepared to hire an individual they have not actually had a chance to meet and assess for themselves. Since the interview is unlikely to be abandoned as a selection tool, it is worthwhile trying to improve its reliability and predictive validity. Research shows that structured interviews developed as a result of a thorough job analysis can increase the validity of the interview to as high as r = .35. Several types of interview methods have been developed to try to assess the criteria identified as important to job performance.

Situational interviews

The situational interview is a type of structured interview which includes a set of questions (based on the job analysis) asking candidates to predict how they would behave in various situations likely to occur in the job, for example, in a customer service role, applicants might be asked how they think they would deal with an aggressive customer in a certain situation. All applicants would be asked such standardised questions as part of the overall interview. The consistency of this approach enables more valid comparison and discrimination between candidates.

Competence-based interviews

While the situational interview asks candidates to predict how they would act in the future, competence-based interviews ask applicants to reflect on their behaviour in the past and to describe an occasion on which they have used a specific ability, for example, how they have managed a situation with an aggressive customer in a previous job.

These structured, job-related interview techniques allow greater comparability between competing candidates than the traditional interview style affords. Additional factors such as training of interviewers, identification of important assessment criteria and agreement of expected standards can also increase the inter-rater reliability between interviewers.

Finally, as with all assessment tools, the validity is likely to increase when the interview is used in conjunction with other information about the candidate such as a personality profile or assessment centre results.

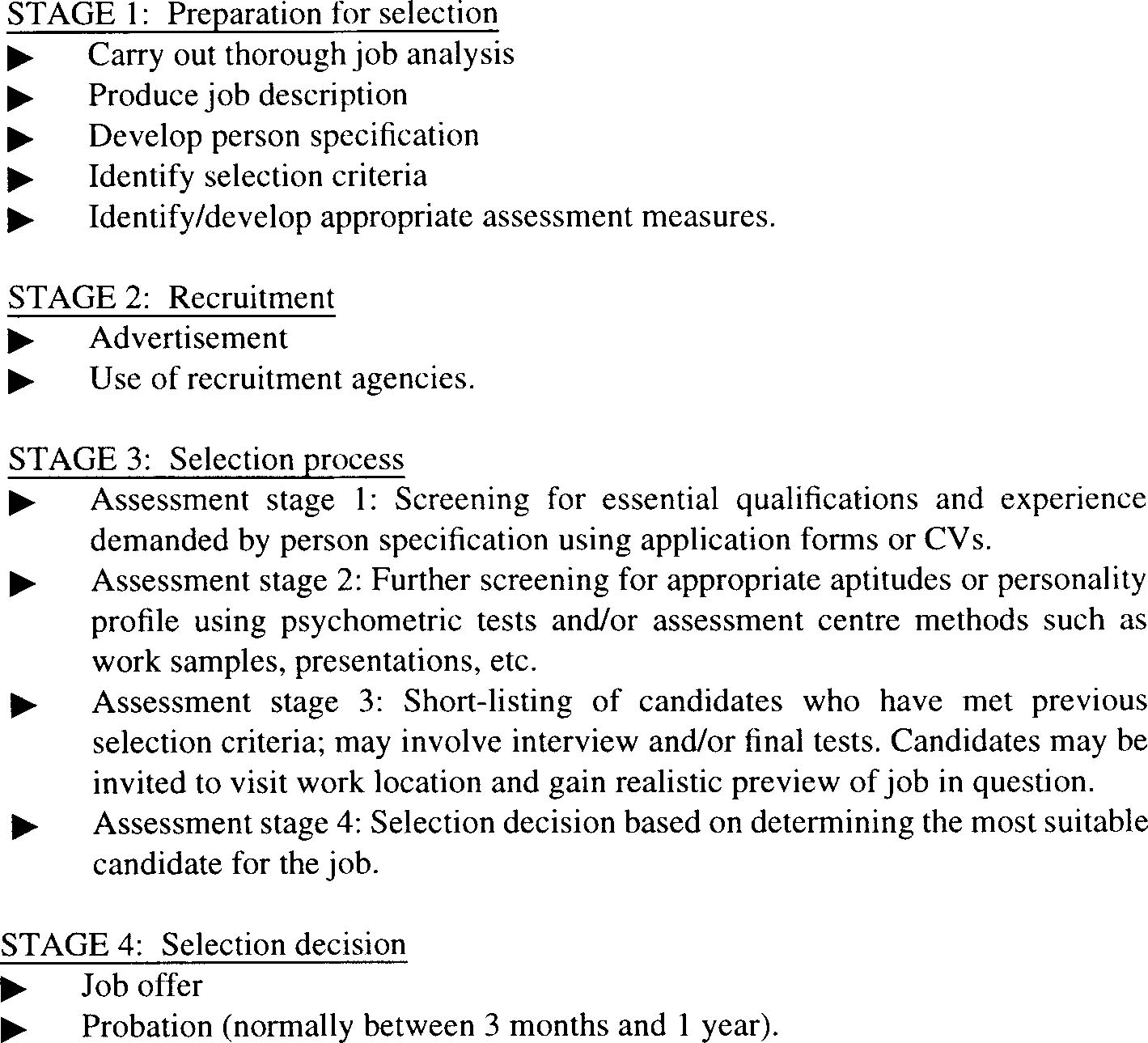

3.12 Choosing a selection method

Torrington and Hall18 point out that although the search for the perfect method of selection continues, HR managers continue to use a variety of imperfect methods in order to cope with the demands of the job. All too often pressures to fill a position rapidly or with minimum expense lead to less than ideal selection processes. For a job vacancy to be filled as suitably as possible, a number of steps are important in order to determine the most appropriate selection criteria and selection methods. In a typical graduate or managerial vacancy, screening and selection of candidates will occur over a number of phases. Figure 3.4 illustrates an example of a typical graduate selection process.

Figure 3.4 Typical graduate selection procedure

As discussed, the complexity, cost and length of a selection process are usually dependent on the level of the job and the calibre of candidate required. The amount of time, effort and money invested in the selection procedure normally reflects the likely impact or value of the potential job holder. For example, those in a position to influence the overall performance of the organisation such as a senior manager or a Chief Executive generally merit more resources than those in junior positions. Some professions, e.g. the military and aviation, have traditionally attracted a great deal of interest in methods for selecting appropriate entrants, where the impact of poor selection decisions may result in disastrous consequences in terms of risk to human life.

Factors which have added greater pressure for the need for effective selection in the 1990s and have influenced the increasing trend towards adopting psychometric measures include:

• The high cost of recruitment and selection processes, coupled with additional cost in terms of lost revenue for lower performance levels during training and ‘settling in’ periods for new staff, ensure the need to try to make a good selection decision and to avoid unnecessary staff turnover.

• Reduced mobility of staff as a result of current labour market trends, meaning that staff are less likely to leave a job of their own accord and, as a result, poor selection choices may impact on the organisation for a long time.

• Legislation, for example equal opportunities and sex discrimination laws, which encourage employers to avoid using unfair or discriminatory selection practices.19

While these factors are important elements for organisations to consider and clearly emphasise the significance of the cost of ‘mistakes’ in the selection process, we must not lose sight of the fundamental reason for trying to ensure the most effective selection procedures: to identify the best person for the job.

3.13 References

1. Bandura A. Social foundation of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1986.

2. Saal F, Downey R, Lahey M. Rating the ratings: assessing the psychometric quality of rating data. Psychological Bulletin 1980; 88: 413–428.

3. Saal F, Landy F. The mixed standard rating scales: an evaluation. Organisational Behaviour and Human Performance 1977; 18: 19–35.

4. Herriot P. Down from the ivory tower: graduates and their jobs. Chichester: John Wiley, 1984.

5. Anastasi A. Psychological testing. New Jersey: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1990.

6. Schmidt F, Hunter J, Urry V. Statistical power in criterion-related validity studies. Journal of Applied Psychology 1976; 61: 473–485.

7. Anastasi, Psychological testing.

8. Kellet D, Fletcher S, Callen A, Geary B. Fair testing: the case of British Rail. The Psychologist 1994; 7(1): 26–29.

9. Premack S, Wanous J. Ameta-analysis of realistic job preview experiments. Journal of Applied Psychology 1985; 70: 706–719.

10. Lane J, Herriot P. Self ratings, supervisor ratings, position and performance. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1990; 63(1): 77–88.

11. Landy F, Farr J. Performance rating. Psychological Bulletin 1980; 87: 72–109.

12. Robertson I, Smith M. Personnel selection methods. In: Smith M and Robertson I eds. Advances in selection and assessment. Chichester: John Wiley, 1989: 89–112.

13. Bevan S, Fryatt J. Employee selection in the UK. Falmer: Institute of Manpower Studies, 1988; Mabey B. The majority of large companies use psychological tests. Guidance and Assessment Review 1989; 5(3): 1–4; Mabey B. The growth of test use. Selection and Development Review 1992; 8(3): 6–8. Williams R. Psychological testing and management selection practices in local government: results of a survey, June 1991. Luton: Local Government Management Board, 1991; Shackleton V, Newell S. Management selection: a comparative study of methods used in top British and French companies. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1991; 64(1): 123–137.

14. Williams R. Occupational testing: contemporary British practice. The Psychologist 1994; 7(2): 11–13.

15. Mabey, The majority of large companies.

16. Arvey R, Campion J. The employment interview: a summary and review of recent literature. Personnel Psychology 1982; 35: 281–322; Schmitt N, Coyle B. Applicant decisions in the employment interview. Journal of Applied Psychology 1976; 61: 184–192; Hunter J, Hunter R. Validity and utility of alternative predictors of job performance. Psychological Bulletin 1984; 96: 72–98.

17. Lane J. Methods of assessment. Health Manpower Management 1992; 18(2): 4–6.

18. Torrington D, Hall L. Personnel management: A new approach, 3rd edition. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall, 1995.

19. Sparrow P, Hiltrop J. European human resource management in transition. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall, 1994.