10 Motivation and rewards

10.1 Introduction

Reward management aims to improve the performance of employees, and this in turn requires positive measures to ensure high levels of motivation. Most organisations try to motivate employees by offering financial rewards in return for skill, time, and effort. Financial rewards alone are generally insufficient to create sustained levels of motivation. Evidence points to the need to adopt measures that satisfy a range of desires which employees bring with them to the workplace, including the desire for satisfactory pay, job security, satisfying work, good working conditions, opportunities to maintain and improve skill levels, status, and good social relationships in the workplace.

Mention was made in Chapter 2 of the need to develop a positive employment policy in order to attract and retain quality staff. Policies in the UK need to take account of survey findings on the attitudes of British workers, such as the recent wide-ranging survey which indicated that British workers were more dissatisfied than those in any other European nation, according to a study of 400 companies in 17 countries,1 and an opinion poll carried out for the GMB union which showed most workers did not regard pay, overtime, or fringe benefits as overwhelmingly important. They were more interested in job security and job satisfaction.2 Basic pay ranked fourth for the men surveyed, and seventh for women. The women surveyed felt that it was more important to work for an employer whom they respected, to have a clean and healthy place to work, and to have a say in how they worked.

Pay systems need to be designed as part and parcel of a total employment package which motivates employees to strive for higher levels of performance. All too frequently company pay systems have had the opposite effect, rewarding years of service and conformity to rules and regulations rather than the employee’s contribution to organisational goals, and involving a minimal expenditure of effort. By applying research findings on motivation, policies and practices can be formulated which contribute to commitment and performance.

This chapter reviews the nature of motivation, its relevance to performance, and theories of motivation appropriate to the management of rewards, as a prelude to a consideration of reward management policies and practices in the following two chapters.

10.2 Motivation

Motivation is a psychological concept related to the strength and direction of human behaviour.3 It is frequently explained as a driving force within individuals by which they attempt to achieve some goal in order to fulfil some need or expectation. There is an implication of deliberate choice by individuals to exert effort; Mitchell defines motivation as ‘The degree to which an individual wants and chooses to engage in certain specified behaviour’.4

In the workplace setting, motivation is concerned with the manner in which individuals choose to exert effort in pursuit of their goals, and, correspondingly, with the manner in which employers attempt to create work environments which stimulate such effort. Understanding motivation at work requires an understanding of the goals which individuals are pursuing, and the manner in which these goals and expenditure of effort are influenced by group dynamics, job design, organisation structure, and financial and other incentives.

Three theories of motivation are particularly relevant to motivating people in work situations. These are the so-called ‘two-factor’ theory, ‘expectancy theory’, and ‘goal-setting’ theory.

10.3 Two-factor theory

The research into motivation conducted by Herzberg in the United States over thirty years ago has been replicated on a number of occasions since, and continues to carry weight today. Based on individual responses to questions as to what provides them with the most memorable instances of happiness or unhappiness at work, people tend to indicate two different sets of factors, one contributing to happiness, the other to unhappiness. Typically, the former list includes:

• a sense of achievement;

• recognition by superiors;

• responsibility inherent in the job;

• satisfying job content;

• promotion.

By way of contrast, the negative factors typically include the following:

• company policy and administration;

• relationships with supervisors and peers;

• physical working conditions.

Pay also attracts comment, some favourable, some unfavourable. This led Herzberg to dub the second list ‘Hygiene’ factors, on the grounds that corrective action needs to take place before positive motivation will result, in the same way that human beings have to observe the rules of hygiene before they can progress to high levels of physical fitness and performance.5

These findings have led to the inference that pay is a hygiene factor, and that employers should therefore focus on achieving a well-administered pay system and erase causes of dissatisfaction among employees, before moving on to the more exciting measures that create high levels of motivation and performance. While there is a large measure of truth in this inference, and experience and research both tell us that it is extremely hard to motivate employees dissatisfied with their pay schemes, it neglects the role that money can have in achieving high levels of motivation. For a significant proportion of employees, particularly high-flying managers and sales staff, financial rewards are an important form of recognition. Money can become a goal in itself, as well as a reinforcing behaviour which leads to high performance.

Herzberg’s findings on motivation are popular with many managers, who can relate to them on the basis of their own work experience, and because they provide a blueprint for action, clearly indicating areas to be tackled in order to improve levels of motivation at work. Critics of Herzberg fasten on weaknesses in his methodology, including his generalisation from a sample consisting of 203 employees in just one company, mostly engineers, accountants, and the like, and that he used a ‘story-telling’ critical incident method, held to introduce bias.6 While further studies by other researchers replicating his methods with samples drawn from other categories of employee have provided support for his findings — and managers are frequently surprised to learn that these show that shop-floor workers also value a sense of achievement and recognition — critics argue that these are the result of the method used. It has also been pointed out that lack of recognition and achievement are also powerful ‘hygiene’ factors.7 However, further studies have lent support to the idea that both extrinsic (hygiene) and intrinsic (motivational) job factors affect job satisfaction in the qualitatively different ways hypothesised by Herzberg.8

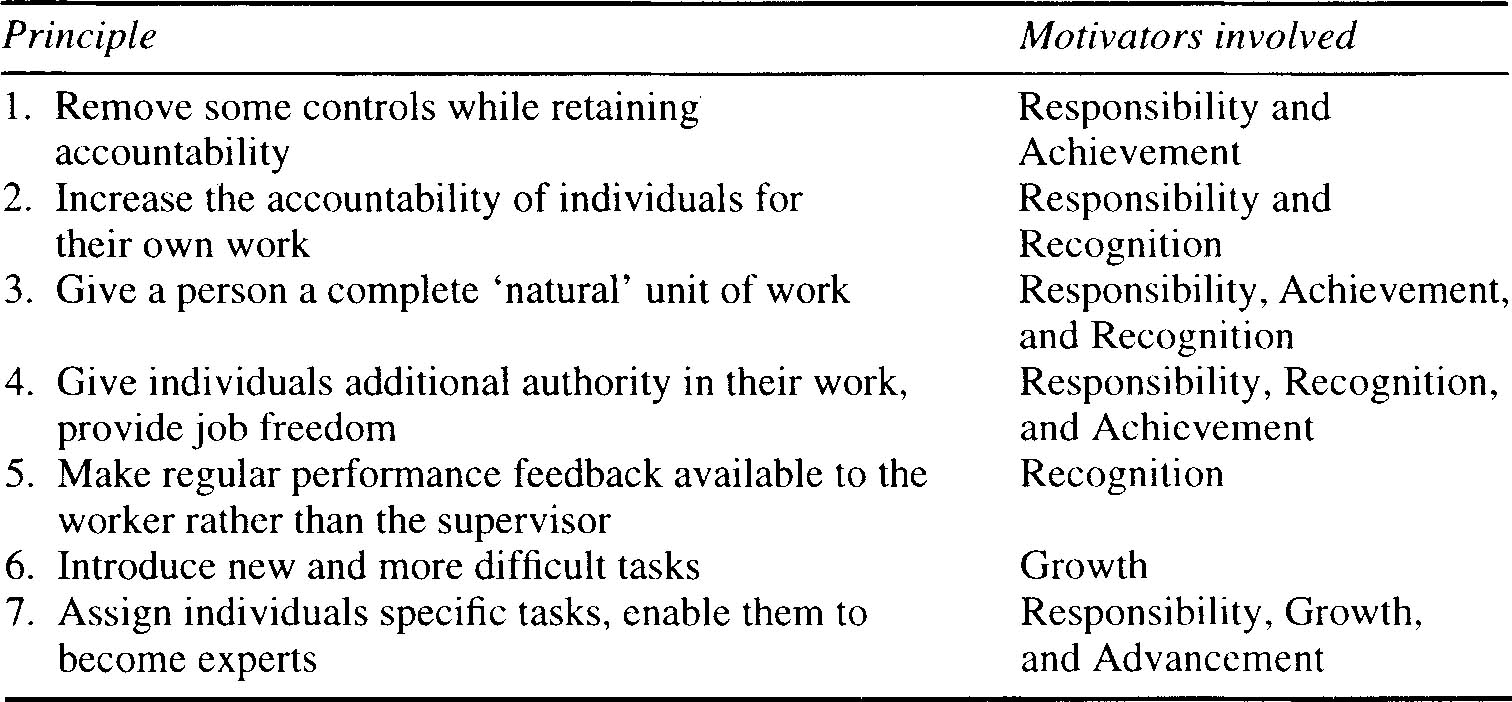

Two-factor theory was associated with the move to redesign and enrich jobs which gained popularity in the 1970s and has recently re-emerged with the drive to multi-skilling in many companies, referred to in Chapter 5. This move to enrich and redesign jobs was given impetus by researchers at the Tavistock Institute, leading to the popularising of the ‘socio-technical’ framework of job design,9 as well as the job characteristics model devised by Hackman and Oldham10 and the ‘requisite-task attributes’ model of Turner and Lawrence11 and Cooper.12 The principles of job enrichment are summarised in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1 A synthesis of the principles of job enrichment

10.4 Expectancy theory

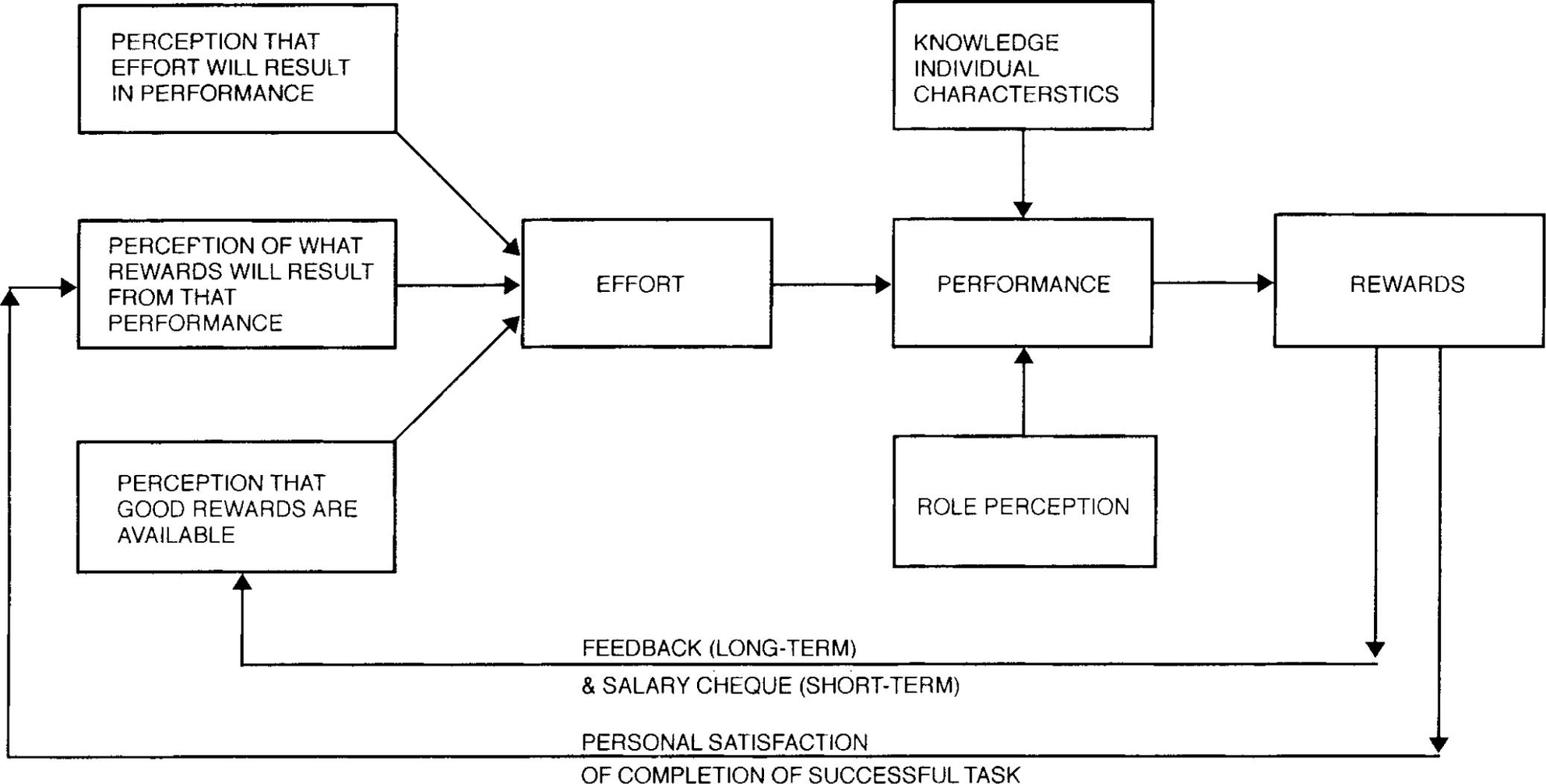

Expectancy theory concentrates, as the name implies, on the expectations which employees bring with them to the work situation, and the context and manner in which these expectations are satisfied. The underlying hypothesis is that appropriate levels of effort, and hence productivity, will only be extended if employees’ expectations are fulfilled. It does not assume a static range of expectations common to all employees, but rather points to the possibility of different sets of expectations. Rewards are seen as fulfilling or not fulfilling expectations. The basic model is illustrated in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Expectancy theory of motivation — applied model

This model emphasises that high levels of performance require clarity about work roles, the selection of workers who possess the appropriate aptitudes and abilities, and subsequent training and job knowledge. Research by Porter and Lawler indicates that the value of the reward, particularly pay, and the perception of the effort-reward relationship combine to influence effort in a positive manner.13 Managers in their sample who perceived their pay to be related to their performance were rated more highly by their superiors than those managers who perceived little relationship.14

The implications for reward management15 include the need to:

• find out what rewards are valued by each employee;

• clarify what constitutes good performance;

• ensure that performance targets can be achieved;

• be clear about the link between rewards and performance;

• check that alternative expectations are not being fostered in other parts of the organisation;

• ensure rewards and bonuses are large enough to attract interest;

• ensure the system is perceived to be fair.

Expectancy theory challenges management to demonstrate to employees that extra effort will reap a commensurate reward. The evidence of research findings and practical experience is that many employees are not convinced that if they exert more effort they will definitely achieve more, and will be rewarded commensurately. Cynicism has been reinforced by, for example, recent performance management schemes offering bonuses of less than 5 per cent in return for extra effort. The link between effort and reward needs to encompass both the pay packet and a variety of other extrinsic or intrinsic rewards. Reward schemes must therefore create a positive link between the size of the pay packet and the effort expended for employees primarily motivated by money. For others, links must be created between effort and rewards which include job satisfaction and praise and other forms of recognition.

10.5 Goal-setting theory

There exists strong evidence that setting goals for employees leads to higher performance, provided the goals are relevant and acceptable to participants. Goal-setting theories, originally propounded by Locke, have considerable relevance to motivation and reward management.16 At a basic level, this means that all employees should:

• be clear about their individual and group goals;

• participate in the setting of these goals.

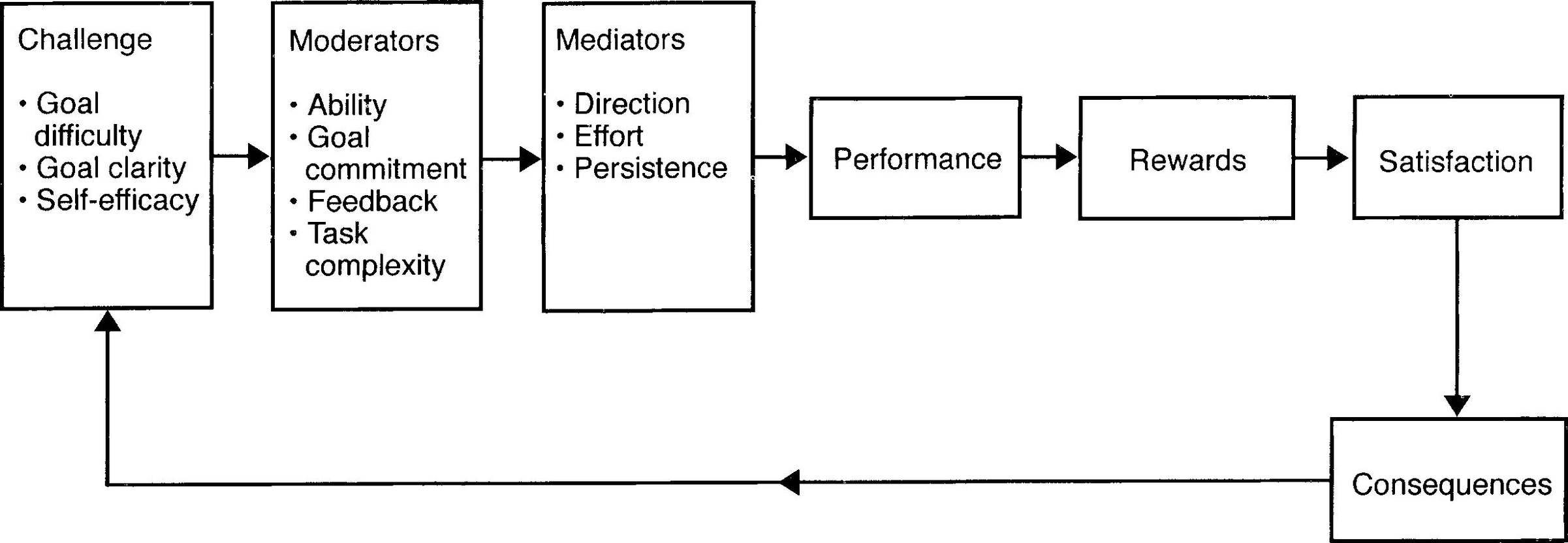

Goal choice is a function of (a) what the individual expects can be achieved; (b) what the individual would ideally like to achieve; and (c) what the individual believes is the minimum that should be achieved. For many people, a goal set and delegated by others serves as a disincentive. For goals to have their full effects it is also necessary for participants to have feedback on whether their performance has been successful. These points are brought out in Figure 10.2.

Figure 10.2 Simplified Locke and Latham goals model

Source: Locke, Latham Goal setting

Difficult goals lead to high performance only when an individual is committed to them.17 As commitment declines, performance also declines. Commitment to a goal can be considerably improved if employees participate in the goal-setting process. Indeed, research suggests that a goal set and delegated by others serves as a disincentive.18 Providing feedback on performance is necessary if goals arc to be fully effective.19

The most obvious applications of goal theory are in managerial style and the design of appraisal schemes. As management is a process of achieving results through people, successful managers will involve staff in goal setting (‘management by objectives’), ensure the goals can be achieved, and provide feedback on whether goals are being achieved. The ‘mushroom theory of growth’ is proverbial (and not attributable!) in much of British industry — ‘keep staff in the dark and shower them with shit’! Where still practised, this leads to poor quality workmanship, and is in stark contrast with the Japanese style of forms of communication and consultation. The styles of communication needed for modern forms of appraisal and performance management are described in Chapters 6 and 12.

10.6 Creating a motivating environment

This chapter has focused on three of the better known theories of motivation in order to bring out the importance of creating a motivating environment when devising reward management policies. Other theories of motivation have also made a useful contribution to current thinking on this issue, notably equity theory20 and control theory.21 Recent thinking about the manner in which a motivating environment at work can be created has been usefully summarised by Ivan Robertson and Dominic Cooper,22 and includes the following characteristics:

• Employees have a realistic understanding of the links between effort and performance.

• Employees have the competence and confidence to translate effort into performance.

• Performance systems are expressed in terms of hard, but attainable, specific goals.

• Employees participate in setting goals.

• Feedback to employees is regular, informative and easy to interpret.

• Employees are praised for good performance.

• Rewards (including pay) are seen as equitable.

• Rewards are tailored to individual requirements and preferences.

• Employee psychological and physical well-being is recognised as important.

• Productivity is recognised as important.

• Jobs are designed, where possible, to maximise skill variety, task identity, autonomy, feedback, and opportunities for learning and growth.

• Organisation and job changes are brought about through consultation and discussion, not by fiat.

The various forms of pay systems and processes in common use are examined in the next chapter, but all must pass the acid test of whether they motivate and encourage effort.

10.7 References

1. Study by International Survey Research, reported in Personnel Management 1991; 11 January: 7.

2. The Times, 9 May 1991:3.

3. Robertson IT, Smith M, Cooper D. Motivation. London: Institute of Personnel Management, 1992.

4. Mitchell TR. Motivation: new directions for theory, research, and practice. Academy of Management Review 1982; 7(1): 80–88.

5. Herzberg F. One more time: how do you motivate employees?. Harvard Business Review 1968; Jan.–Feb.: 53–62.

6. Vroom VH. Work and motivation. Chichester: Wiley, 1964.

7. House RJ, Wigdor LA. Herzberg’s dual-factor theory of job satisfaction and motivation: a review of the evidence and a criticism. Personnel Psychology 1967; 20, Winter: 369–390.

8. Robertson IT et al. Motivation: 58.

9. Emery FE. Designing socio-technical systems for greenfield sites. Journal of Occupational Behaviour 1980; 1(1): 19–27.

10. Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Work redesign. New York: Addison Wesley, 1980.

11. Turner A, Lawrence PR. Industrial jobs and the worker: an investigation of response to task attributes. Boston, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, 1965.

12. Cooper R. Task characteristics and intrinsic motivation. Human Relations 1973; 26: August: 387–408.

13. Porter LW, Lawler EE. Managerial attributes and performance. New York: Irwin, 1968.

14. Porter LW, Lawler EE, Hackman JR. Behaviour in organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975.

15. Nadler DA, Lawler EE. Motivation: a diagnostic approach. In: Steers R, Porter LM eds. Motivation and work behaviour, 2nd edn, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

16. Locke EA. Towards a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance 1968; 3: 157–189.

17. Locke EE, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting and task performance. London: Prentice Hall, 1990.

18. Naylor JC et al. Goal setting: a theoretical analysis of motivational technology. In: Straw BM, Cummings LL eds. Research in organizational behaviour 1980; 6: 95–114.

19. Erez M. Feedback: a necessary condition for the goal-setting performance relationship. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1977; 62(5): 624–627.

20. Klein HJ. An integrated control theory model of work motivation. Academy of Management Review 1989; 14: 150–172.

21. Greenberg J. A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review 1987; 12: 9–12.

22. Robertson IT, Cooper D. Motivation: evolution or revolution?. Paper presented to Institute of Personnel Management Annual Conference, Seminar 51, 1993.