12 Appraising and rewarding performance

The quest to link rewards to performance has a long history. One of the earliest approaches, payment by results, was examined in Chapter 11. As jobs have come to require greater and greater amounts of discretion by job holders, and as the service sector has grown in significance, traditional forms of work measurement have become less and less relevant, and new approaches have been developed, frequently seeking to improve future performance, rather than simply rewarding what was perceived as good past performance. As a result many appraisal schemes have incorporated elements of ‘management by objectives’, and more recently, attention has been paid to so-called ‘performance management’ schemes that attempt to link individual objectives with corporate and departmental goals. At the same time many companies have been developing competency profiles for their jobs, and have consequently attempted to link rewards with the manifest capacity to carry out a good job of work. All three approaches can be found today in many organisations.

12.1 Appraisal

Carried out properly, appraisal is an essential part of good management, stimulating a two-way flow of useful information between managers and subordinates that continuously clarifies roles and objectives and engenders support in the pursuit of mutually agreed goals. Appraisal is considered in this chapter in the context of reward management, although it also has a significant role in training and development and in career planning. Opinion is divided over the use of appraisal for both pay and development purposes. Those who favour limiting its use to development argue that linking it to pay can undermine attempts to provide honest feedback and an emotion-free review of strengths and weaknesses and participative setting of targets.1 Those who support the linking of appraisal to pay argue that pay should be seen to be linked to performance in order to increase motivation and to establish the credibility of pay decisions. There can be no right or wrong answer to this dilemma; as with most management decisions of this nature, it all depends on key variables present in the situation.

Because so many problems have arisen in the past in the design and implementation of appraisal schemes, many have questioned their worth.2,3 The principal argument in favour of formalised appraisal schemes is that they place the process of subjective judgement onto a more objective basis, a basis moreover that is open to scrutiny. The principal arguments against formalised appraisal schemes are that a high proportion have failed to meet their objectives, and in the process have alienated both staff and management, and that the process of formalisation leads to the bureaucratisation of what should essentially be a natural process. It is possible, however, to develop appraisal schemes that avoid these mistakes, and make a really useful contribution to the objectives of the organisation, reward good performers, help all employees to do better, and enhance the personal sense of achievement of all concerned. The principal considerations, based on research evidence and examples of best practice, are enumerated below.

The first consideration is clarity concerning aims. Is the aim primarily to improve current performance, to ascertain staff development needs, or to reward high performers? The evidence from research and practice is that no system can achieve all these aims simultaneously. But the biggest mistake is to think that the introduction of an appraisal scheme can by itself rectify serious defects in the manner in which an organisation is managed. Therefore before introducing formal appraisal a management audit needs to be carried out, asking such key questions as:

• Has the organisation a clear mission and a well-thought-out corporate strategy?

• Has it communicated these to employees?

• Are managers well trained in managing people?

• Do attitude surveys indicate high levels of job satisfaction?

Having satisfied these preliminary considerations, decisions must be taken about how formalised the appraisal scheme needs to be. The critical question here is the extent to which the organisation needs to be run on bureaucratic or decentralised and flexible lines. A bureaucratic hierarchical structure requires a matching highly formalised appraisal system based on well-defined job descriptions. However, very few organisations these days can afford to be bureaucratic, because bureaucracies cannot adapt easily to change, and for most organisations the environment is undergoing rapid change. Therefore, most organisations will require appraisal systems that are both simple and flexible, and easy to operate.

The third consideration is just what is to be appraised. The evidence from research and experience is that the primary focus should be on the achievement of results, and not on personality traits. Individuals can do very little to change their personalities, but they can do much about improving their performance. This indicates that appraisal forms should focus on the results aimed for, and whether they are being achieved.

The fourth consideration is how to measure or ‘appraise’ performance. This requires realistic quantifiable targets, with specific time spans for their achievement. Measurement can then concentrate on the extent to which results are being achieved by a due date.

The fifth consideration is participation. To what extent should subordinates participate in the setting of performance aims? As brought out in , the evidence is that other things being equal, the more individuals genuinely participate in the setting of goals, the more committed they are to achieving them, the more likely they are to improve their performance.

The sixth consideration is training, both the training and development of subordinates and of superiors. Subordinates will need training and development in order to achieve targets, and superiors carrying out appraisal will need training in the skills of appraisal. Many managers do not find appraisal an easy job to carry out, and lack the skills to conduct appraisal interviews. Appropriate investment in training is essential.

The seventh consideration is timing. Should appraisals be once a year, or more frequent? Traditionally appraisal has been conducted once a year in order to coincide with the annual salary review, linked in turn to the financial year. But a one-year cycle is rarely appropriate to work tasks. Work tasks may have natural cycles that range from days to months or even years. Therefore it may be right to conduct appraisals (‘performance reviews’) at any time in the year to mark the conclusion of relevant tasks or projects.

The final consideration is ‘ownership’. The appraisal scheme must be ‘owned’ by those who operate it, and this usually means line management. A scheme foisted on to managers by HRM colleagues will not work if it is not perceived as being helpful. This calls for considerable consultation and delegation, and at the same time a degree of monitoring and evaluation to ensure that schemes work well.

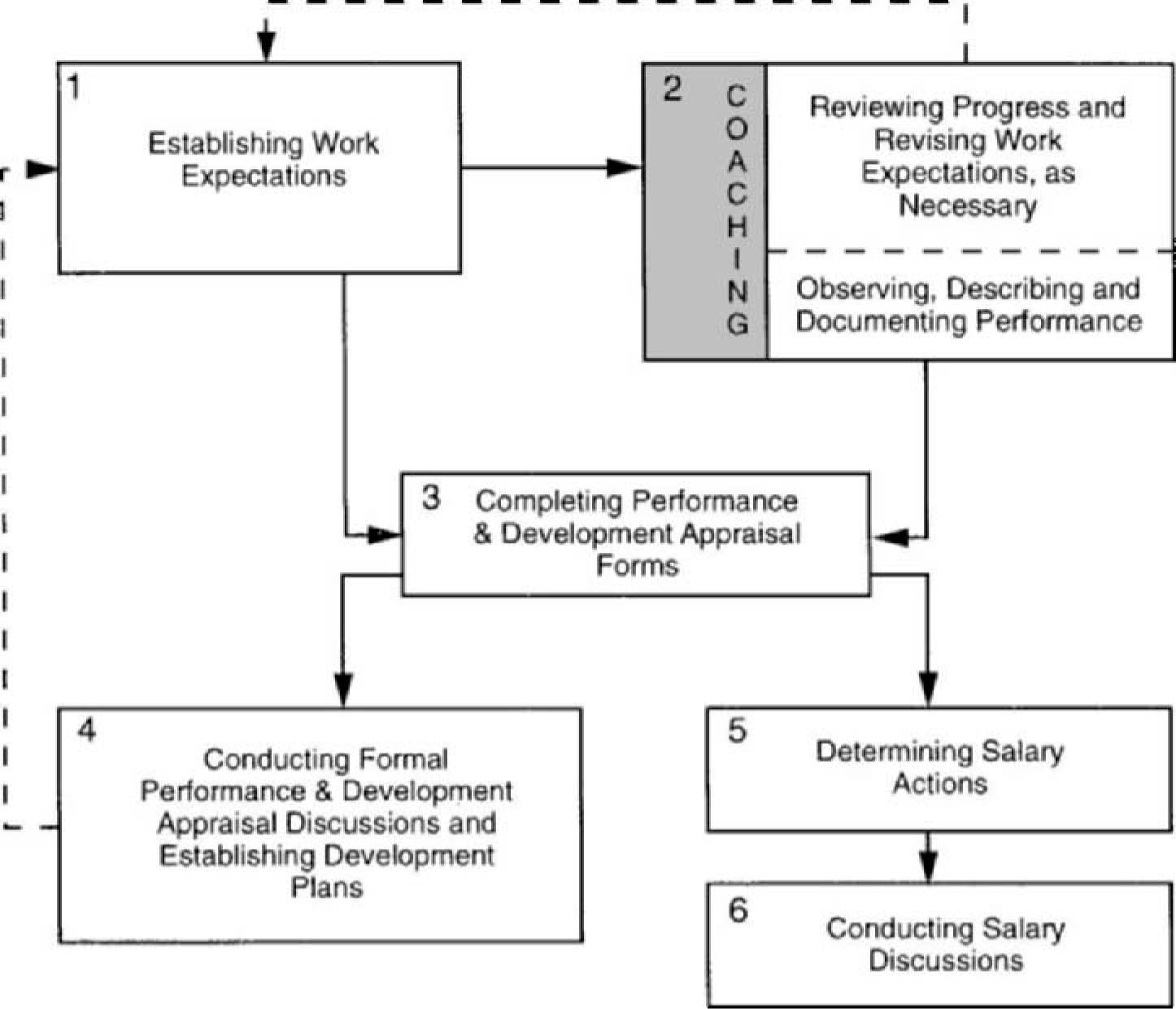

The basis of a good appraisal system planned and administered on conventional lines is brought out in Figure 12.1.

Figure 12.1 Conventional company performance appraisal process

Source: Page RC, Tornow, WW, Personnel Administrator, January 1985

Note the emphasis on coaching in Figure 12.1. Line management has the primary responsibility in high-performance organisations for coaching and developing their staff.

12.2 Behaviour scales

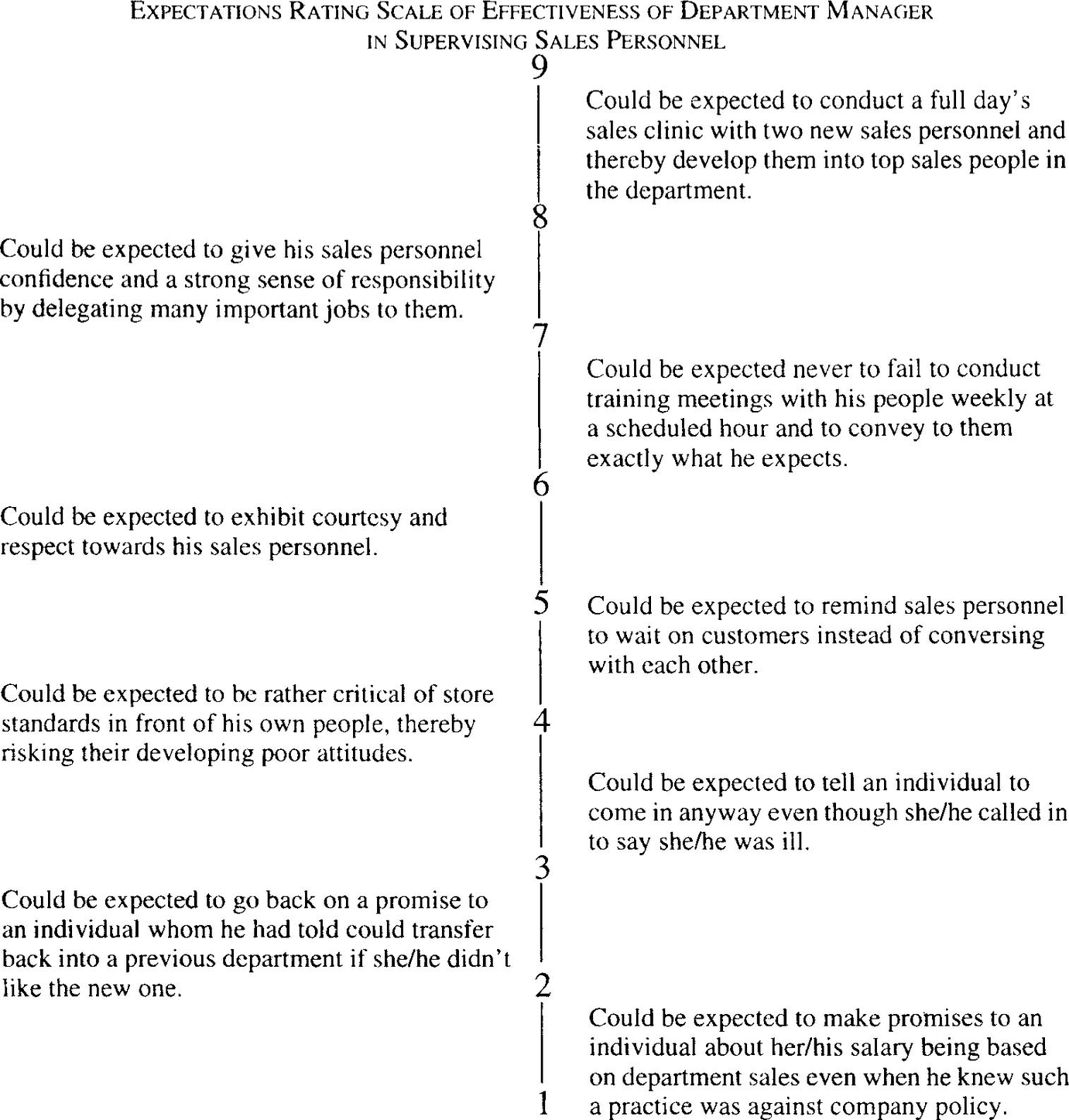

On the grounds that it is behaviour rather than personality that should be appraised and rewarded, many appraisal schemes include behaviour scales. Competency schemes, examined below, represent a form of behaviour scale.

Behaviour scales describe a range of behaviours that contribute to a greater or lesser degree to the successful achievement of the cluster of tasks which make up a job. Supervisors conducting an appraisal are asked to indicate which statements on the specially designed form most accurately describe a subordinate’s behaviour. A sophisticated version of this approach is represented by ‘Behaviourally Anchored Rating Scales’ (BARS). Statements about work behaviour are used to create scales, which must then be tested to confirm their relevance and precision. This is a time-consuming process, and although a number of claims for its success have been made, further evaluation is needed.4 An example is provided in Figure 12.2.

Figure 12.2 Behaviour rating scale

Source: Journal of Applied Psychology 1973, 57: 15–22

12.3 Multiple rating in appraisal

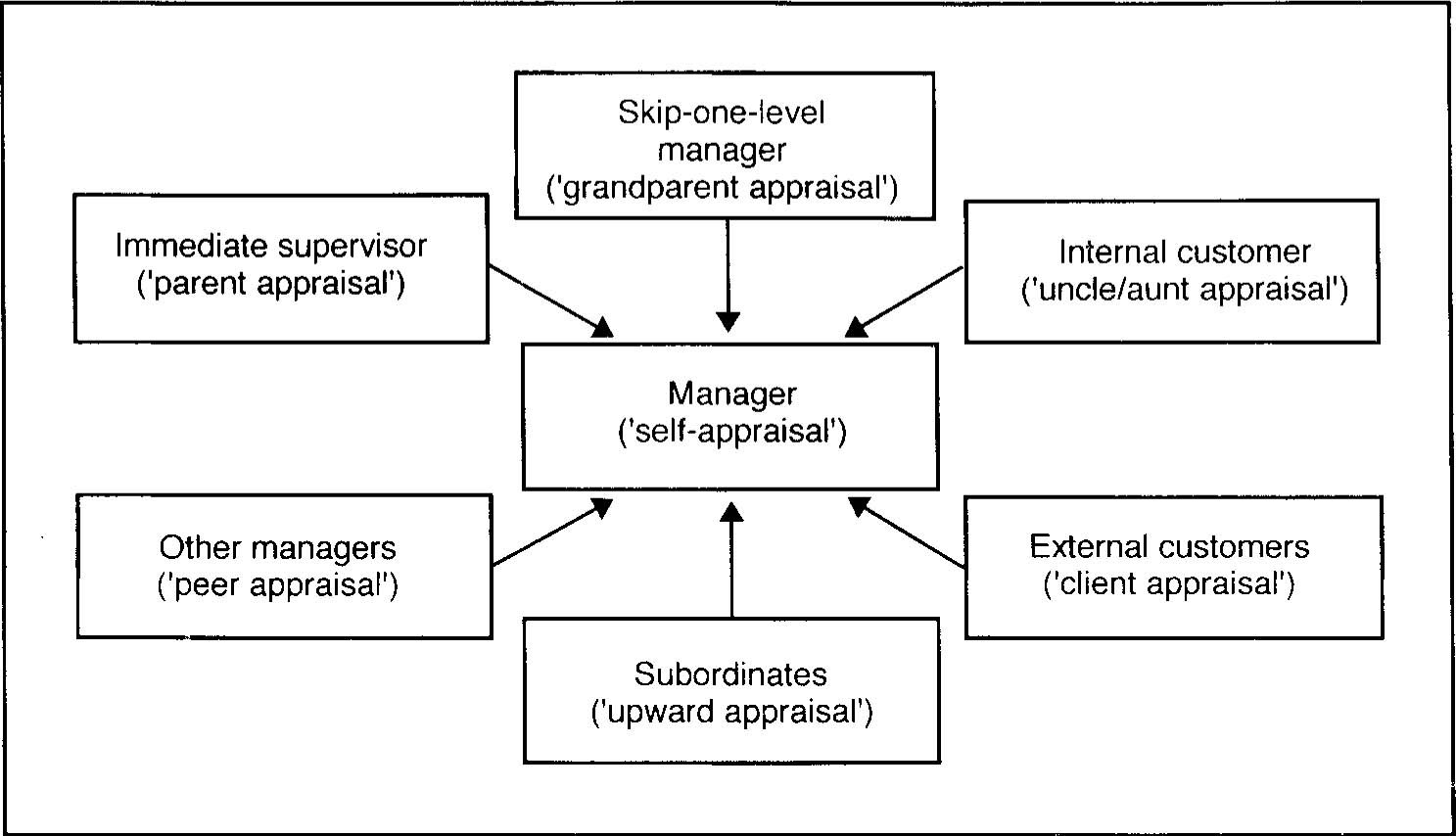

Traditional appraisal systems have involved just the appraiser and the appraisee. Recent developments in appraisal have seen a move away from one-to-one rating towards multiple rating, which in turn may involve lateral and upward appraisal. Flatter organisation structures, moves to empower employees, participative leadership styles, the recent emphasis on self-development rather than course attendance, and the possible trauma induced by downward appraisal in the appraisee, have led many leading companies to forms of multiple assessment. The best known version is the so-called ‘360 degree appraisal’, in which comment on performance is provided by subordinates and peers as well as superiors. The range of possible options is illustrated in Figure 12.3.

Figure 12.3 Potential appraisers in a multi-appraisal system for managers

Source: Redman T, Snape E, Personnel Review 1992; 21(7): 33

Typical large organisation 360 degree appraisal schemes are designed to enable the principal ‘stakeholders’ in a person’s performance to comment and provide feedback. This may include the boss, direct and indirect reports, peers, and internal and external customers.5 Information is usually collected through questionnaires. The locus of the appraisal thus shifts from a formal one-to-one appraisal interview situation to one where feedback is received in the less hostile environment of the normal place of work, and support by counselling and assistance is then offered as appropriate. Confidentiality for the appraisee and anonymity for the respondents is clearly very important.

Possible pitfalls include a negative emphasis, lack of confidentiality, poor communication, lack of support, and that traditional British failing, a ‘flavour of the month’ approach. Research evidence on the effectiveness of these types of schemes in improving organisational performance is still limited but the potential benefits of broadening the base of appraisal appeals to many companies.6 Strong reservations are still expressed about linking multi-appraisal to pay review. A recent survey showed 81 per cent of top UK companies limiting it to staff development purposes.7

Another recent development has been the introduction of the so-called ‘balanced score card’. This measures management performance across a range of categories, employing multiple feedback that can include both staff and customer comments. Typically, staff may be asked to complete a questionnaire concerning the performance of their management team, and this will influence the size of the pay rise accorded to their managers.8

12.4 Performance management

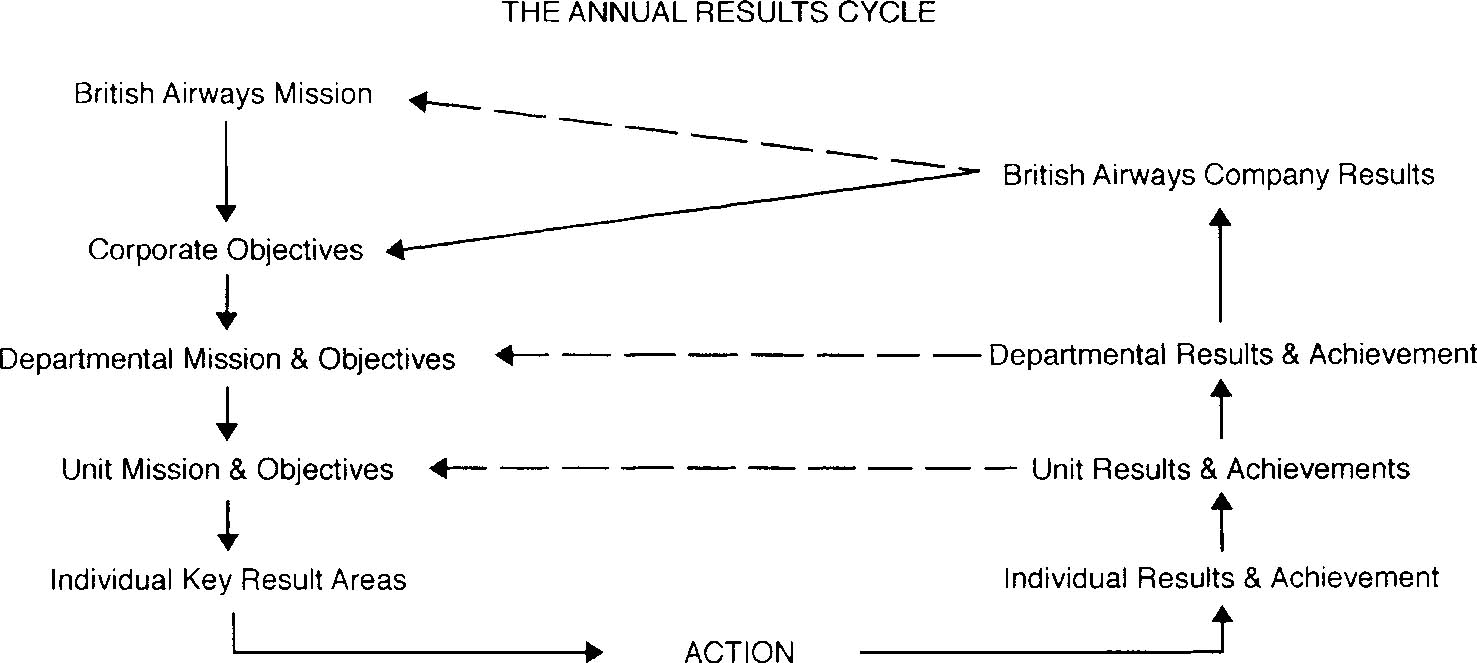

Performance management is a comprehensive term describing a process in which employees participate with their superiors in setting their own performance targets. These targets are directly aligned with the stated goals of their departments. As part of the process, employees are provided with the training and resources needed to achieve their targets, and are rewarded for achieving these targets. In this way rewards and appraisal are specifically linked into an organisation’s mission and goals, in a manner rarely achieved in traditional appraisal schemes.9

Well-developed performance management systems will usually incorporate the following items:

• a statement outlining the organisation’s values;

• a statement of the organisation’s objectives;

• individual objectives which are linked to the organisation’s objectives;

• regular performance reviews throughout the year;

• performance-related pay;

• training and counselling.

An example of this system in practice is shown in Figure 12.4.

Figure 12.4 Performance management, company annual results cycle

On the face of it, performance management appears to be a sensible way of managing any organisation. However the evidence is that only one-fifth of large organisations have adopted a performance management approach.10 The success of performance management can be restricted by any of the following:

• a reactive rather than pro-active strategy;

• insufficient involvement by line management;

• a climate of fear;

• over-emphasis on bottom line results;

• introduced simply as a performance-related pay scheme;

• too much red tape.

But when these mistakes have been avoided, or have been rectified, the results are usually beneficial.11 It is not yet possible to demonstrate a long-term link between performance management and economic success, but when properly executed it represents a more sensible system of motivating and rewarding staff than the old-fashioned bureaucratic systems it has been replacing.

12.5 Pay for skills

Traditionally skilled workers have been paid more than their less skilled fellow workers. New technology means that unskilled jobs are disappearing rapidly and there is now an emphasis on quality, team working, and adaptability. This in turn requires new skills and new attitudes. In order to acquire and retain a workforce with appropriate skills, and support the acceptance of new values and attitudes, some employers are linking rewards directly to the acquisition of relevant skills.12 For this to work, the amount of money attached to the acquisition and demonstration of a relevant skill needs to be sufficient to encourage employees to make the necessary effort.

Skills-based pay (SBP) is on the increase in both the manufacturing and service sectors. Nearly one-quarter of employers responding to an IPM/NEDO survey said that they had introduced changes to their payment systems in the past two years aimed at encouraging the acquisition of new skills.13

The two most common approaches are to pay one or more skill supplements linked to the acquisition of skill modules, or to create higher pay grades for those with extra skills. Research by Incomes Data Services established that in their case study, companies’ payments per module ranged from about £200 to £700, the average being about £300.14 The second approach is to create a separate multi-skilled pay grade. In such cases, multi-skilled status is more likely to be seen as promotion and the precise pay level may depend on the nature of the subsequent job.

Having decided on multi-skilling, an employer needs to create a training programme to equip craft workers with the requisite skills. In many cases training is linked to national NVQ or City and Guilds standards.

Experience to date indicates that it is not suitable for all situations, requires careful planning, and needs to be preceded by a more participative and open system of working. Significant resources need to be devoted to training, which includes training in new skills and in team working. Rewards need to be linked not only to the acquisition of skills but to their application, and possibly also to the performance achieved.15

12.6 Competency-based pay

A widely used definition of competency describes it as ‘an underlying characteristic of an individual which is casually related to effective or superior performance in a job’. A working definition of competency, used in a large UK telecommunications company, describes it as ‘a combination of skills, knowledge, behaviour and personal attributes which together are necessary to perform a job effectively and which provide the basis for an objective and consistent review of performance and development needs’. Competencies can include motives, traits, self-concepts, attitudes or values, content knowledge, or cognitive or behavioural skills.

At the level of the organisation, a process of isolating and measuring so-called ‘core competencies’ is required. It is these core competencies that can then be used for selection, training, and reward management purposes. A summary list for senior managers might include the following:

• analytical thinking;

• pattern recognition;

• strategic thinking;

• persuasion;

• use of influence strategies;

• personal impact;

• motivating.

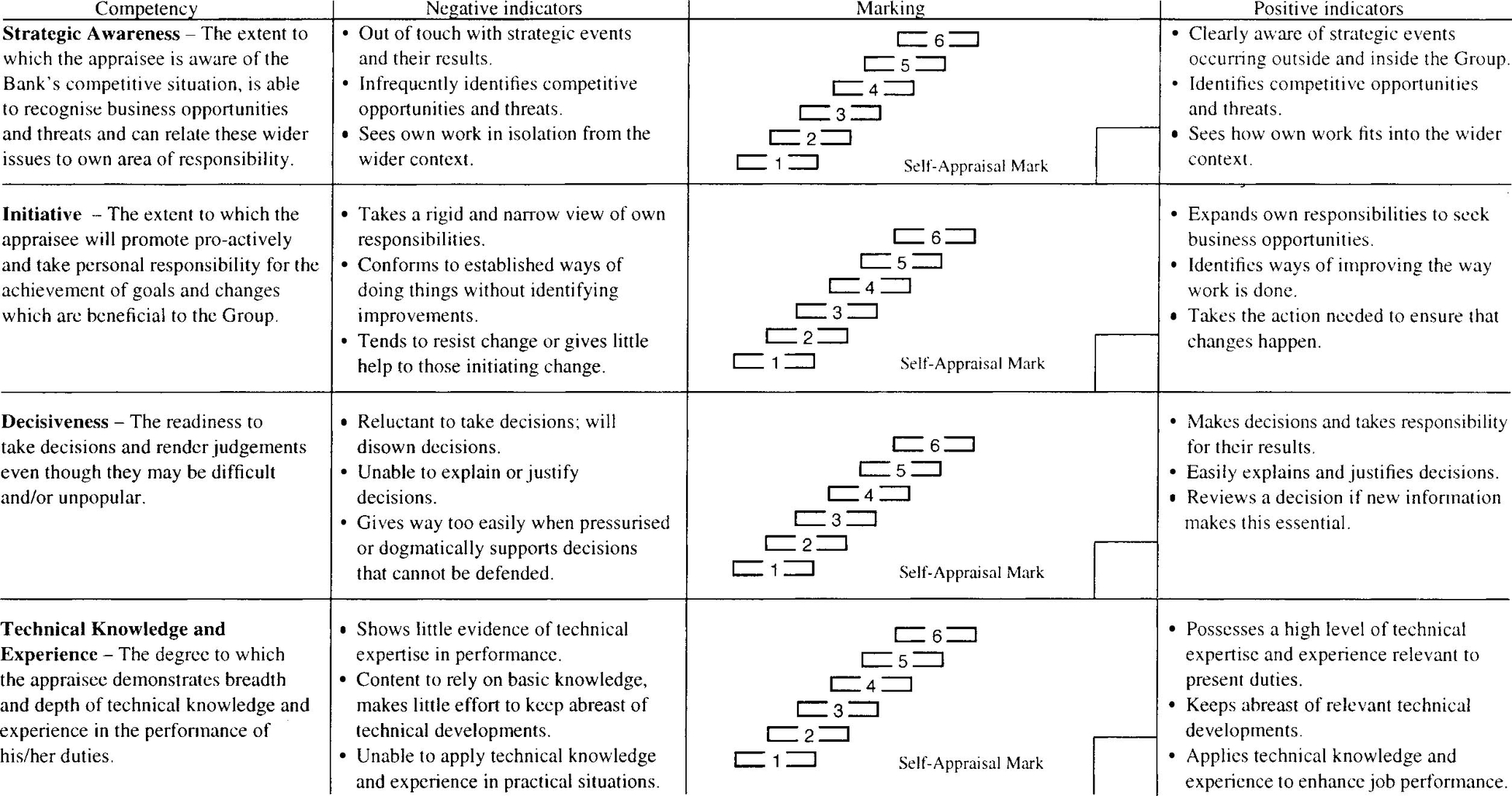

Figure 12.5 Typical competency-based appraisal scheme for bank managers

These can be built into the appraisal system, and rewarded according to standards attained in each area. Linking competencies to explicit forms of behaviour ensures that they are linked to the type of performance which contributes to organisational goals. Figure 12.5 provides an example of competencies built into a company appraisal scheme.

A job family may consist of a number of competency bands, each of which constitutes a definable level of skill, competency and responsibility. Individuals move through these bands at a rate which is related to their performance and their capacity to develop.16 There are three different types of competency-based pay structures – narrow-banded, broad-banded, and performance pay curves, all associated with job families.

Competency-based pay currently takes two different forms. One makes pay contingent on achieving certain levels of competency: if competency increases, then so does pay. The other is that of evaluating and grading jobs in relation to competency. A recent study in the UK found considerable interest in competency-based job evaluation schemes, but no widespread take-up. The survey also found considerable confusion and disagreement on the nature and definition of competencies, and warns against paying for the acquisition of competencies rather than their effective use in the workplace.17

Implementing skill-based and competency-based pay schemes requires a considerable investment in time and the establishment of procedures. Care must be taken to ensure that the cost of this investment and the imposition of over-elaborate procedures do not outweigh the benefits of these schemes.

12.7 References

1. Fletcher C, Williams R. Performance appraisal and career development. London: Hutchinson, 1985.

2. McGregor D. An uneasy look at performance appraisal. Harvard Business Review 1957; 35(3): 89–94.

3. Latham M. Job performance and appraisal. In: Cooper CL, Robertson I eds. International review of industrial and organisational psychology. Chichester: Wiley, 1986.

4. Campbell JP et al. The development and evaluation of behaviourally based rating scales. Journal of Applied Psychology 1973; 57: 15–22.

5. Ward M. A 360 degree turn for the better. People Management 1995; 9 Feb.: 20–25.

6. Redman T, Snape E. Upward and onward: can staff appraise their managers?. Personnel Review 1992; 21(7): 32–46.

7. Platt S. Viewed from all angles. Personnel Today 1996; 22 October: 45–7.

8. Littlefield D. Halifax employees to assess management. People Management 1996; 8 Feb.: 5.

9. Yeates JD. Performance appraisal: a guide for design and implementation. IMS Report No. 188. London: Institute of Manpower Studies, 1990.

10. Fletcher C, Williams R. The route to performance management. Personnel Management 1992; October: 45–47.

11. Incomes Data Services Ltd. Performance management. London: IDS Study 518, November 1992.

12. Edward E, Lawler M. Paying the person: a better approach to management?. Human Resource Management Review 1991; 1(2): 145–154.

13. Cross M, Cannell M. Skills-based pay: a guide for practitioners. London: Institute of Personnel Management, 1992.

14. Incomes Data Services Ltd. Skill-based pay. IDS study 500. London: IDS, February 1992.

15. Incomes Data Services Ltd. Paying for multi-skilling. London: IDS Ltd, IDS Study 610, September 1996.

16. Armstrong M, Murlis H. Reward Management, 3rd edn, London: Kogan Page, 1994.

17. Institute of Personnel and Development. Survey on job evaluation. London: IPD, 1995.