9 Equal opportunities

9.1 Introduction

In the economic climate of the late 1990s many authors advocate that organisations should behave in strategic, pro-active ways in order to gain competitive advantage and thereby survive as effective operations. The principles of managing human resources indicate that competitive advantage can only be achieved through the efficient utilisation of employees at all levels.

The fundamental starting-point must be to ensure that, in the first place, a balance of different types of people are recruited into an organisation and once inside are developed, promoted and retained. To achieve this ‘balance of diversity’ there must be available a pool of applicants for all vacancies (external or internal), open to everyone equally, and there should be no discrimination against individuals who may be disadvantaged due to their belonging to a specific group. Disadvantaged groups who traditionally suffer discrimination include women, disabled people and people from certain racial groups or ethnic backgrounds that are in the minority within the potential workforce, and older workers.

An organisation made up of diverse groups, containing a wide range of abilities, experience and skills, is more likely to be open to new ideas and different possibilities than one which is more homogeneous in terms of worker background and experience. While the ethical case for equal opportunities is a strong one, it will be the economic case that will be the deciding reason for organisations to take note of equal opportunities and implement effective policies.

The real issue for the future is not whether any particular group achieves equality, but whether the UK can compete successfully internationally if all groups of people are not treated as equal. Statistics produced by the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) and the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) indicate that in the future, not only will there continue to be high unemployment but also a parallel skills shortage in Great Britain. The reasons for this shortage of skill development in our current and potential workforce are complex and not discussed here. However, continued lack of availability of appropriate skills will force employers to look at traditionally under-utilised groups, whether they are groups such as women, ethnic minorities, disabled or older workers. This latter group are currently not protected by employment legislation in the UK.

There are two ways in which action can help to overcome the disadvantages these groups suffer. One is to influence attitudes and preconceptions held by our society about them and the other is to introduce and implement legislation to prevent discrimination. Influencing attitudes is a very slow process. It may take more than one generation to filter through society. Indeed, the debate relating to whether it is possible to change attitudes and behaviours at all fills many chapters in texts about organisation behaviour.

Legislation has been introduced intermittently since the mid-1970s in an effort to reduce the disadvantages these groups experience. But as Ross and Schneider (1992)1 point out, statistical evidence over the past 20 years indicates that the law is not a particularly effective vehicle for influencing change in attitudes or in practice. The future labour market situation may leave organisations with little alternative but to alter traditional thinking. Their approach reflects the assumption that the law merely sets out minimum standards and that there are compelling business reasons for embracing equal opportunities.

In 1991 Joanna Foster,2 in her role as chair of EOC, said, ‘Equal Opportunities in the 1990s is about economic efficiency and social justice’, and while the case for equal opportunities has been argued on moral and ethical grounds, economic reasons are central, with the law providing the modus operandi. The law has played a valuable role in defining and outlawing discrimination against particular groups. Some discussion of legislation relating to equal opportunities is set out later in this chapter. This should be read in conjunction with Chapter 8 which covers all key aspects of UK law on equal opportunities.

Both CRE and EOC have played and continue to play important law enforcement and campaigning roles. Let us hope that the newly formed National Disability Council (NDC) will aid the implementation of the recent disability legislation — Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

In view of these developments, we can but wonder why in practice so little progress has been made in equal opportunities. Cooper and White (1995)3 believe that the reasons may be related to the fact that the positions of power in UK organisations are dominated largely by white males. ‘Therefore those who are in the best position to promote change have no personal experience of discrimination.’ This view is supported by an EOC report (1995)4 showing that in specific employment sectors, such as banking, building societies and post offices, men in managerial positions totalled 68 per cent of all managers. Similarly, only 31 per cent of medical practitioners were women. Latest figures5 for the total UK workforce show that 45 per cent of the workforce is female. Nevertheless, women’s earnings have begun to increase. In 1975 they were at 71 per cent of male earnings; by 1995 this figure had improved to 80 per cent of male earnings — a modest improvement perhaps when we consider that equal opportunities legislation has been in force for over 20 years.

Women employees

There are over 5 million part-time workers in the UK, 87 per cent of whom are women and the numbers are rising. Pay for part-time work is often lower despite the Equal Pay Act. Recent changes to part-time employees’ employment protection enforced by European Community legislation will perhaps begin to have an impact shortly and we should see an improvement in women’s pay relative to that of men. However, we should also realise that over 2 million female part-time workers earn so little or are so sporadically employed that they do not pay National Insurance, have no entitlements to unemployment benefits, sickness pay or state pensions, and therefore the true picture of equality is rather blurred by official statistics since they do not feature in them.

Disabled employees

Estimates are that there are 3.9 million people, over 10 per cent of the potential UK workforce, with some impairment or disability affecting their ability to gain employment.6 It is expected that employment legislation under the Disability Discrimination Act, which came into effect in January 1997 to protect disabled people, will have a positive effect on the numbers of disabled employed over the next decade.

The law has nevertheless impacted on some areas of discrimination, most notably in the area of recruitment advertisements. The incidence of discriminatory practices in recruitment advertising has reduced dramatically over the past 20 years. It is, however, more difficult to ascertain the degree of change in equality of opportunity for the female workforce in relation to training and promotion practices within organisations. Firm evidence to support the belief that discrimination is diminishing for women within organisations would require detailed national research. In the absence of this, however, it is clear from material appearing in the national press as well as details held at Companies House for limited companies and also published annual company reports that there are more female directors in businesses now than was the case 20 years ago.

Ethnic minority groups

Unemployment among ethnic minority groups is notably higher than that of the white population; indeed, it currently stands at ‘about double that for the white population, even when age, sex and level of qualification were taken into account’7 and when employed, a far higher proportion of ethnic minority groups work in unskilled manual jobs than do the white population. Thanks to monitoring figures, many organisations now have data showing that they employ more ethnic minority employees than they did 20 years ago. But research carried out by O’Neilly (1995)8 shows that these employees are often discriminated against when seeking promotion opportunities: ‘there is a real danger, not only that an organisation will fail to make the best use of its prime resource, but that future cohorts of good ethnic minority recruits will look at the workforce, read the message and take their talents elsewhere’. This echoes my earlier comments that to succeed in business we must promote equality of opportunity to all.

This chapter outlines the legal framework and regulatory bodies set up to support the legislation within the UK, considers aspects of diversity and discusses equal opportunity policy and practice with reference to some of the organisations who have been working to reduce discriminatory practices in the workforce.

9.2 The legal framework and regulatory bodies

Legislation aimed at eliminating or vastly reducing inequalities of opportunity in employment was first introduced in the UK in 1965 and 1968 with the Race Relations Acts, later replaced by the Race Relations Act 1976. 1970 saw the introduction of the Equal Pay Act, followed by the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. More recently the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 was introduced. By joining the European Community (EC) in 1973, the UK accepted the terms of the Treaty of Rome. This had some impact on our equal rights legislation. Subsequently, certain amendments have been made to UK law where appropriate.

In brief, the current legal position in the UK is that organisations are required not to discriminate against individuals on grounds of race, sex, marital status or disability in selection for employment. In addition, the law states that employees be treated equally in respect of rewards including benefits, training and promotion once they have been employed. Also if the situation should arise where redundancies or short time working are under consideration by an employer, all employees regardless of race, sex, marital status or disability should be treated equally and not be subject to discrimination.

The nature of discrimination

Racial or sexual discrimination can be direct or indirect. Direct discrimination occurs when a person is treated less favourably than another person on grounds of sex or race. Indirect discrimination occurs when a person (employer) applies to one person (employee) the same requirement or condition which he applied to another but:

1. which is such that the proportion of employees in that racial group who can comply with the condition is considerably smaller than the proportion of people not of the employee’s racial group who can comply with it; and

2. which is to the employee’s detriment because he/she cannot comply with it; and

3. which the employer cannot show to be justified irrespective of the sex (colour or ethnic or national origins) of the person to whom it is applied.

Indirect discrimination is well illustrated by the case of Manila v Dowell Lee [1983] IRLR 209, where the complaint resulted from a requirement for male school children to wear school caps. It was a requirement with which a smaller proportion of Sikhs could comply than could non-Sikhs because Sikhs customarily wear turbans. The schoolboy in this case could physically comply with the requirement but, in practice, for religious reasons, was unable to do so.

Positive discrimination

Both the Sex Discrimination Acts 1975 and 1986 and the Race Relations Act 1976 make it lawful to encourage and provide training for people of one sex or racial group who have been under-represented in particular work in the previous 12 months. However, although advertisements can explicitly encourage applications from one sex or racial group, all other applicants must also be treated fairly and no discrimination must be allowed to take place.

Equal pay

The Equal Pay Act 1970, as amended by the Equal Pay (Amendment) Regulations 1983, and the Sex Discrimination Act 1986, established the right of women and men to be treated equally with regard to terms and conditions of employment when they are employed on the same or broadly similar work or work which, though different, has been given equal value under a job evaluation scheme, or work which is of equal worth in terms of the demands of the job. It applies equally to men and women and to full-time and part-time employment.

Of course there are different jobs within the workplace, some of which may justifiably be paid at a higher rate and the lower paid jobs may by coincidence be carried out by women. So that even when it is proved that the woman is doing similar work, she will have no right to equal pay if an employer can show that there is a material difference, not based on sex, between the two employees which justifies the difference in payment. What constitutes a material difference in one instance, may be irrelevant in another; as is usual, it all depends on the facts of each case.

Sex discrimination

The Sex Discrimination Act 1975, as amended by the Sex Discrimination Act 1986 and the Employment Act 1989, makes it unlawful to discriminate on grounds of sex or marital status in a number of specific situations related to the employment situation, for example, in the recruitment and selection process; in the provision of access to promotion, transfer or training, or to any other benefits, facilities or services normally provided to employees.

Sex discrimination is not unlawful where a person’s sex is a ‘genuine occupational qualification’ for the job. Each Act includes the specific circumstances in which discrimination may be permitted, for example, in a single sex prison or hospital or where there is a need for certain welfare, educational or similar services to be provided by a person of a particular sex. Further details are given in Chapter 8.

Sexual harassment

Although sexual harassment is not mentioned specifically in the legal provisions relating to sex discrimination or unfair dismissal, complaints may be brought to an industrial tribunal under either of these of these headings in certain circumstances. Sexual harassment was defined by the European Commission Council of Ministers in 19909 as

conduct of a sexual nature, or other conduct based on sex, affecting the dignity of women and men at work, including conduct of superiors and colleagues if:

• such conduct is unwanted, unreasonable and offensive to the recipient;

• a person’s rejection of or submission to such conduct is used explicitly or implicitly as a basis for a decision which affects that person’s access to vocational training, access to employment, continued employment, promotion, salary or any other employment decisions; and/or

• such conduct creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating work environment for the recipient.

Complaints of sexual harassment may constitute sex discrimination where it is established that the claimant has been treated in a way which would not have been applied to someone of the opposite sex in the same circumstances, and that this treatment has resulted in some loss such as disciplinary action, dismissal (actual or constructive), transfer or failure to promote or train.

Race discrimination

The Race Relations Act 1976 makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person, directly or indirectly on grounds of race, in the field of employment. Discrimination occurs when, on racial grounds, a person is treated less favourably than others would be treated, or is segregated from others and there is ostensibly equal treatment in that a requirement or condition is applied to all people, but the number of people in a particular racial group who can comply with it is proportionately smaller than the number of people outside it who can comply, and the employer cannot justify the requirement as necessary to the job.

Indirect discrimination can occur where, for example, employers require higher language standards than are needed for the safe and effective performance of the job.

Although generally prohibiting discrimination in employment, like the Sex Discrimination Act, this Act allows race discrimination in certain circumstances such as genuine occupational qualification of the job, for example, in modelling, photographic work, welfare services to a particular racial group and in public restaurants where authenticity requires members from a particular racial group.

Racial harassment

Racial harassment can be a form of racial discrimination concerned not with practices and procedures but more with individual behaviour of one person towards another. Employers must ensure that their employees are not racially harassed either by their colleagues or by the public and any other external contacts, while carrying out their duties.

Racial harassment may involve racist insults and ridicule, jokes, display of racist literature, the use of racist names, and so on.

Disability Discrimination Act 1995

The Disability Discrimination Act 1995, which came into force in January 1997, makes discrimination against disabled people for a reason related to their disability unlawful in the field of employment and places a duty of ‘reasonable adjustment’ on employers with more than 20 employees, to help overcome practical difficulties caused by employers’ premises or working practices. The Act applies to employees, job applicants and contractors who are disabled physically or mentally.

The Code of Practice accompanying the Act provides general guidance and outlines the reasonable steps required by employers as ‘reasonable adjustment’. Although not a legally binding document, the Code will have a strong influence on the operation of industrial tribunals who will have to consider the practicalities of making adjustments to premises, working methods, hours of work, etc. as well as the costs (to the employer) of making these changes, and the degree of usefulness of any such changes to the disabled employee. A company may be justified in refusing to make high cost adjustment for a temporary employee but would be expected to meet such a cost for a permanent member of staff.

It is too early to estimate the Act’s impact on the employment of disabled people, but it will certainly affect the way organisations view disabled people and their employment. As James and Bruyere (1995)10 observed – the Act imposes new obligations on employers with regard to the management of workplace disability and ‘the challenge of the new Act demands much more than the review and development of appropriate policies and procedures but also that organisations improve the coordination existing between all of those involved in the prevention and handling of disability at work, including occupational health staff, safety advisers, line managers, human resource management, safety representatives’.

National Disability Council

Introduced in tandem with the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, to advise the government, the National Disability Council (NDC), unlike CRE and EOC, has not been given the status of an Employment Commission and cannot represent individuals at industrial tribunals. Litigation is thus in the hands of disabled individuals who may or may not be able to afford to fight a claim, or feel confident to do so by virtue of their disability. We may find that employment lawyers will be willing to take the first few test cases for disabled clients without fee so that they can become the ‘experts’ in disability industrial tribunals. The change in government in May 1997 may see the Council upgraded to Commission status with more power to exert some influence in this area. Only time will tell.

Age discrimination

The protection of older workers is not covered by legislation in the UK in spite of attempts by some politicians to introduce legislation. By the year 2000, 26 per cent of the total UK population will be aged over 55, yet latest national figures available11 show that the participation rate of older people in economic life is declining.

Although a handful of firms in the UK have operated successful policies to attract older people (e.g. B&Q over-50s’ advertising campaign) as employees, it is still the practice of many organisations to place advertisements or include a maximum age in their selection criteria for job applicants. At present, much of the debate about age discrimination concerns treating older workers less favourably, but it may also be discriminatory to treat younger employees less favourably. As we move towards the millennium, it may depend on UK government policy, or stronger influence by the European Union to alter the situation with regard to legislation on age discrimination.

Equal Opportunities Commission

The Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC), established in 1976, works towards the elimination of discrimination, promotes equality of opportunity and keeps under review the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and the Equal Pay Act 1970. It further promotes research and activities of an educational nature and in consultation with the Health and Safety Commission, keeps under review certain health and safety legislation which requires men and women to be treated differently. It has produced a Code of Practice which gives guidance on the steps considered reasonably practicable for employers to take to promote equality of opportunity and to eliminate discrimination in employment. In 1996 EOC published a Code of Practice on Equal Pay to provide practical guidance and to recommend good practice on pay provision in organisations. This has drawn on decisions from the UK courts and the European Court of Justice (ECJ) as well as good practice known to EOC. The Code gives guidance on drawing up an equal pay policy as well as a suggested policy outline.

The Commission may also represent an individual claiming discrimination on grounds of sex against an employer at an industrial tribunal.

Commission for Racial Equality

The Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) was set up by the Race Relations Act 1976 to work towards the elimination of discrimination, to promote equality of opportunity and good relations between persons of different racial groups and to keep under review the working of the Act.

The Commission has issued a Code of Practice on Employment. It has powers to institute formal investigations where there is some evidence of discrimination and can issue a non-discrimination notice following an investigation and obtain an injunction from a County Court if a non-discrimination notice is not being complied with within 5 years of its issue.

It has also produced a ‘Standard for Racial Equality for Employers’ with the aim of helping employers develop racial equality strategies and to measure their impact. While the Standard does not have legal status, it seeks to provide a link between the Code of Practice on Employment and the broader strategies favoured by employers when working with communities and clients.

The Commission may also represent an individual claiming discrimination on grounds of race against an employer at an industrial tribunal.

Monitoring

Monitoring signifies checking, recording and analysing data. It is of necessity a bureaucratic system but if it helps employers to recognise and deal with discrimination, whether on grounds of race or sex or both, then it achieves its purpose. The CRE Code of Practice states that employers should regularly monitor the effects of selection decisions and personnel practices and procedures in order to assess whether an equal opportunities policy is being achieved.

The EOC recommend that employers retain records of the breakdown of applications received from men and women, the breakdown of successful appointees as well as the breakdown of staff and seniority of staff within their organisations. At the recruitment stage, both CRE and EOC suggest that records of applicants and interviewees be retained for three years, so that if an employer is challenged by a candidate complaining of discrimination, the gender and racial breakdown of external applicants and those within the organisation can be provided for any investigations. Both Commissions recommend that ethnic and sex monitoring information be kept separate from the application forms or curriculum vitae when processing candidates and the names of candidates should not be known to the people responsible for short-listing as names could indicate the sex or racial origin of candidates.

For monitoring to succeed, candidates need to know why information is sought by prospective and current employers. For example, the reasons for asking ethnic questions should be stated on job application forms and on staff surveys for ethnic monitoring purposes and confirmation that any details given will be protected from misuse must be made clear to those completing such forms. Recommended methods of keeping and collecting monitoring data are available from both Commissions. The National Disability Council (NDC) recommends that similar activities be carried out by organisations for the monitoring of disability in employment.

9.3 Diversity or equal opportunity?

The terms ‘diversity’ and ‘equal opportunity’ are used, often interchangeably, to describe initiatives which can help to remove barriers to employment for people in society. Diversity and managing diversity are increasingly used by employers, not only as an alternative, broadly equivalent term to equal opportunity, but also as a redefinition or redirection of equal opportunity policy development.

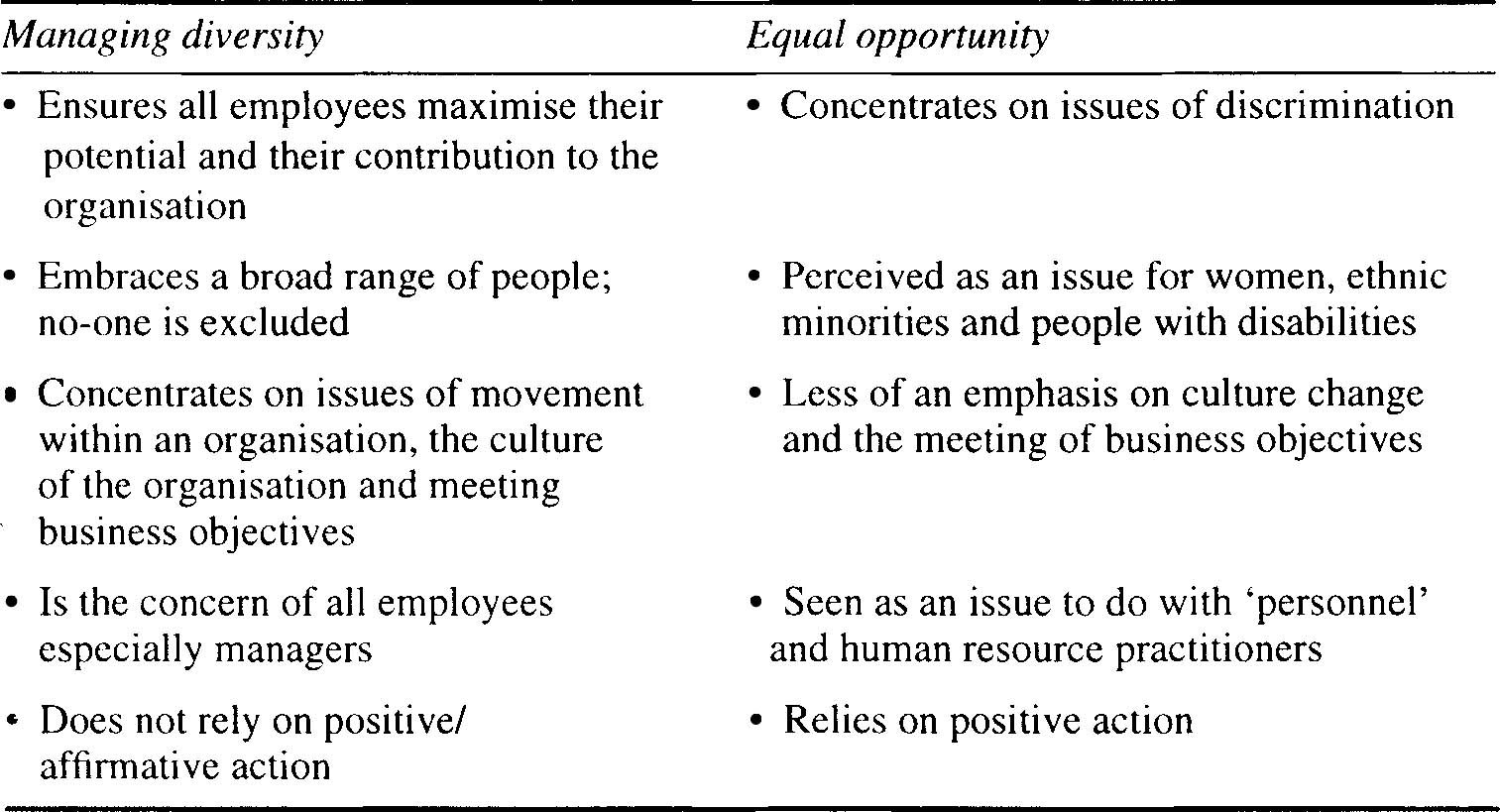

Managing diversity relies on the concept that the workforce consists of a diverse population of people. Diversity recognises that people differ, not just in the more obvious ways of gender, ethnicity, age and disability but in visible and non-visible ways including background, personality, culture, work styles and approach, etc. Kandola and Fullerton (1994)12 clarify the difference between equal opportunity and diversity as being that equal opportunity theories of the 1960s and 1970s were more concerned with assimilation and integration of minority groups, whereas diversity recognises that harnessing people’s differences will create a productive environment in which everybody feels valued and where their talents are being fully utilised and in which organisational goals are being met. This is summarised in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Differences in approach between diversity and equal opportunity policies

Source: Kandola, Fullerton, Diversity

The concept of diversity has aided managers as they strive for long-term change in organisations. The value that it places on the differences between people has helped to motivate employees and to increase productivity.

Comments on diversity from the Institute of Personnel and Development have focused on ways of maximising individuals’ potential and contribution to organisations. Worman (1996)13 states ‘managing diversity is not just about concentrating on issues of discrimination, but ensuring that all people maximise their potential and their contribution to the organisation … it is a concept which embraces a broad range of people’.

Commentators on ‘diversity’ and ‘equal opportunities’ have remarked that they are not and should not be seen as an alternative to equal opportunities. The two concepts are interdependent. For example, Ford (1996)14 points out that equality and diversity have an impact on all people management processes, from the nature of the employment contract, hours and place of work, through compensation and benefits, to employee behaviour and attitudes that welcome rather than fear differences. Ford feels that whatever definition an organisation uses for equality and diversity, the important fact is that, by adopting such a strategy, the organisation is working for commercial success.

The CRE (1996),15 while welcoming the concept of diversity as a positive overall objective with equal opportunities as an essential and integral part, has anxieties about diversity policies in general. ‘If diversity policies produce no progress towards racial equality we will continue to champion the need for specific equality measures to achieve this. Diversity policies which produce no racial equality impact will also be producing little that is of real benefit to their employees.’

Different but equal: diversity in practice

Organisations such as SmithKline Beecham have adopted diversity as a way forward; recruitment advertising in 1996 states:

Make no mistake about it, discrimination is a major part of SmithKline Beechams’ employment strategy; what’s more, we’re proud of it. After all, we want to ensure that only the best people join us. So we ruthlessly reject anyone who doesn’t make the grade. But gender, colour, race, religion, nationality, disabilities or sexual orientation don’t come into it. Why should they, unless they affect your ability to do the job? Because that’s what concerns us when we receive an application. In other words we are more interested in individual qualities like commitment, talent, energy and creativity.

The company benefits hugely from an integral diversity and equality policy. It’s not merely a matter of legislation; it’s sound business strategy. We realise that people from different backgrounds bring individual skills and approaches. Besides, we want a workforce which accurately reflects the community.

Bernard Fournier, managing director, Rank Xerox has explained his company’s policy in the following terms:

Equality and diversity are about creating an environment where everyone is treated equally, whatever their race, religion, sex, colour or any other type of difference. I see differences as a source of enrichment. To be successful we have to be creative and apply diverse perspectives to business problems. Everyone should be able to contribute and should progress in the company in relation to his or her ability.

Rank Xerox16 describes its objectives as qualitative and quantitative. It aims to:

• create an environment where management can respond positively to differences in the people who work for Rank Xerox, its potential employees, its customers and its suppliers;

• encourage everyone to contribute to their full potential — based solely on their ability, competence and performance;

• challenge the traditional workplace culture and work patterns to eliminate barriers;

• introduce measurable goals for a more diverse workforce profile that reflects the skills, talents and experience available.

9.4 Equal opportunities policies

Recommendations from the CRE, EOC and NDC are that organisations should develop written equal opportunities policies embracing recruitment, promotion and training, all of which should be clearly linked to the aims and objectives of the organisation. They also stress the importance of communicating the policy to employees and their representatives, where applicable, to applicants and potential applicants, customers and clients, shareholders, suppliers of goods and services as well as external bodies such as Training and Enterprise Councils and the public.

To create a written policy, a step-by-step approach is advisable:

1. Develop outline draft policy.

2. Prepare an action plan including targets for senior management, detailing responsibilities for policy implementation, resources for any changes necessary to fulfil the policy, timetables for action and implementation and intended methods of measuring effectiveness.

3. Arrange consultation with all employees and their representatives and any external specialist advisory bodies.

4. Provide training for all employees including all senior managers to ensure consistency of approach and an overall understanding of the importance of equal opportunities. Arrange specific training for those people responsible for recruitment, selection, appraisal interviewing and training.

5. Carry out an audit to review current procedures for recruitment, selection, appraisal or performance review, disciplinary and grievances, promotion, training, health and safety, selection criteria for redundancy, transfer and redeployment.

6. Write clear and justifiable job criteria for each job in the organisation to ensure that they are objective and job-related.

7. Consider pre-employment training, where appropriate, to prepare job applicants for selection tests and interviews.

8. Examine the feasibility of flexible working schemes such as career breaks, job sharing, flexitime, shift work, childcare, prayer breaks or areas for prayer, etc.

9. Set up monitoring systems adjusting documentation for recruitment accordingly, to collect appropriate information as necessary for monitoring.

10. Larger organisations should introduce an Equal Opportunities Committee to maintain a positive approach to the issues surrounding equality of opportunity and to review equal opportunity in practice.

11. Finally, agree the equal opportunities policy and set a regular review date to ensure that it is kept up to date.

Managing equal opportunities

Over 25 years have now passed since the first legislative steps were taken to eliminate unfair discrimination in the workplace and we have seen a vast range of different approaches unfolding within organisations. The public sector was the first to respond and some rather bureaucratic systems were implemented which sometimes served to make the situation more complex than it needed to be. Many organisations now have separate policies for racial strategy, equal opportunity on grounds of sex, disability equality, and diversity policies. There is no right or wrong approach. It is up to each organisation to design policies and procedures to fit with their individual approach to business operations and culture while adhering to the spirit and intention of legislation.

One organisation to have implemented equal opportunities strategies for business reasons is Frederick Woolley Ltd, a Birmingham manufacturing firm, investigated by Parkyn and Woolley (1994).17 In 1991 the organisation was facing both the effects of recession and demands for increased quality from customers. The company developed an equal opportunities programme which became an integral part of its strategy for survival as it took steps to move from traditional methods of production. The firm was family-owned and run by an all-male management team with 36 per cent of its workforce being female. These workers were under-utilised and under-valued by the firm. The company had to involve and empower its employees in order to develop an appropriate change strategy to meet the new philosophy of continuous improvement.

They recruited their first female director and an equal opportunities programme was instituted to demonstrate how positive action could increase women’s participation in employment, especially in non-traditional female areas including management. They set up an equal opportunities project steering group to highlight the traditional, restrictive ways of deploying women, together with a summary of how these limitations had been affecting the bottom line of the business. Many changes were made to implement the new ideas from the project team including targeted training for women, assertive communication skills for both sexes, new recruitment and promotion procedures. The equal opportunities strategy was a most successful part of the overall new approach to business strategy and the financial position of the company improved dramatically as a result of the many initiatives put in place.

A different approach which worked well was introduced by the WH Smith Group who conducted an Employee Profile Audit in 1995,18 to collect accurate employee data on all 30 000 UK employees. They started by publishing explanatory articles in the in-house magazine, then team briefings took place around the group and question and answer leaflets were prepared for managers. Next, they issued personal information forms to employees asking them to check the accuracy of personal data such as date of birth, grade, and so on. In addition, employees were asked to state their ethnic origin and whether they considered themselves disabled. Some 84 per cent of the forms were returned showing the importance that staff themselves attached to this audit. Following the audit, the company produced a very practical working document containing a number of checklists suggesting ways in which the businesses in the WH Smith Group could take action to improve the diversity of their workforces. The report will be updated and reviewed regularly.

The Group has also supported many initiatives such as one to help unemployed ethnic minority young people find permanent employment. Pre-employment training has also been introduced for a group of unemployed people in London. They have revised their application forms which are now regularly monitored and each business within the group has set up ‘diversity action teams’, consisting of senior line managers and staff representatives, to plan and monitor further action.

Another example is in the financial sector: Midland Bank has introduced 8 weeks’ paid summer work experience for ethnic minority students at the end of their penultimate year at university,19 offering an insight into banking and an opportunity to develop particular skills. High calibre participants are encouraged to apply for entry to the bank’s graduate programme. Midland Bank have publicised the project extensively in the national and ethnic minority press and radio, and all university career offices now have application forms.

The bank now organises induction and development training to introduce candidates to Midland Bank and the graduate recruitment process uses assessment facilities to provide instruction in interview techniques as well as written exercises, with feedback on performance.

For Midland Bank the benefits are that they now receive more applications from ethnic minority graduates, a group previously under-represented and untapped as a source of supply of highly educated labour. In addition, managers within Midland have increased their own cultural awareness with the added benefit that this must bring to all staff.

A further example of interest is British Petroleum (BP)20 whose equal opportunities policy handbook highlights the purposes of the policy:

An equal opportunity policy is important for the individual. But it is also important for the company. Such a policy helps to identify, attract and make the best use of the skills and talents we need to conduct our business efficiently, wherever these may be available. In essence, race, religion, colour, nationality, ethnic or national origins, sex or marital status must not influence, directly or indirectly, the way in which a person is treated.

The policy goes on to detail each employee’s responsibilities in relation to equal opportunities as well as mechanisms for dealing with situations of perceived inequality.

Finally, in British Gas21 the approach to equal opportunity policy is to break it down to embrace different aspects of equality and provide specific actions the organisation has taken to redress the balance of race and sex. For example, the policy relating to women’s issues revolves around ‘family friendly’ approaches; for example, childcare vouchers issued to female employees; career breaks with a guaranteed job after a 2-year break and preference over external applicants given to returners after a 5-year break. Flexible working arrangements such as variable hours, flexitime and job sharing have also been introduced. Similar policies exist for other equal opportunities issues.

Evaluating equal opportunities policies

In order to achieve success, policies must be supported by senior management and trade union leaders and not simply become ‘top-down’ initiatives or simply the concern of specific groups. Leiff and Aitkenhead22 make the point that, ‘Equal opportunities policies are often said to fail because they are not promoted enthusiastically enough or are not implemented in a comprehensive enough manner.’ It is vital that any equal opportunities policies introduced into an organisation not only have the support of all employees but must be seen as a necessary and beneficial activity to the organisation. As already mentioned, influencing attitudes is a slow process and not always easy, but sound policies for equal opportunities and supportive training programmes may do much to influence behaviour and may, over a period of time, alter attitudes. Clearly there has been much progress in the moves towards equalising opportunities in the workplace thanks to the initiatives of companies leading the field.

9.5 The future of equal opportunities

The essence of much of the work involved in managing human resources effectively, according to Torrington and Hall (1995),23 involves discrimination between individuals but the essence of equal opportunity is to avoid unfair discrimination.

As this chapter has attempted to convey, equal opportunity is not only about meeting legal and social responsibilities but also about attaining organisational effectiveness. The ‘diverse organisation’ of the future will be part of the formula for success if the UK is to be competitive on an international basis.

Every organisation will need to develop and build on its own particular experiences of equal opportunities and diversity and will aim for different objectives. Rather than trying to follow a single formula for success, it is up to management to initiate the best policies and practice for their unique environment. In this way will evolve changes necessary to provide the optimum climate in the firm to foster talent, performance and creativity so vital to organisational effectiveness and growth.

9.6 References

1. Ross R, Schneider R. From equality to diversity: A business case for equal opportunities. London: Pitman, 1992.

2. Foster J. Launching the equality agenda. Conference EOC, London, 1991.

3. Cooper C, White B. Organisational behaviour. In: Tyson S. Strategic prospects for HRM. London: IPD, 1995.

4. Some facts about women. London: EOC, 1995.

5. Equal Opportunities Commission. Guidance notes for employers: setting targets for gender equality. London: HMSO, 1995.

6. Dryden G. Post-16 Policy, RNIB. IPD North London Branch Meeting, 1996.

7. Equal Opportunities Commission. Guidance notes for employers: successful positive action. London: HMSO, 1994.

8. O’Neilly J. When prejudice is not just skin deep. People Management 23 Feb 1995: 34–37.

9. European Commission. Council of Minister’s Report. Brussels: 1990.

10. James P, Bruyere S. Handling disability — implications of the new law. Occupational Health Review 1995; Nov./Dec.: 21–24.

11. Labour force survey. London: HMSO, 1996.

12. Kandola R, Fullerton J. Diversity: more than just an empty slogan? Personnel Management 1994; Nov.: 46–50.

13. Worman D. Diversity: code of practice. London: IPD, 1996.

14. Ford V. Partnership is the secret of progress. People Management 1996; Feb. 8: 34–37.

15. Commission for Racial Equality. Case study no. 2. London: HMSO, 1996.

16. People Management 1996; 8 February: 46–50.

17. Parkyn A, Woolley S. Learning to give women an equal input. Personnel Management 1994; June: 20–24.

18. Employee profile audit. London: WH Smith, 1995.

19. Work experience handbook. Midland Bank, 1995.

20. Equal opportunity: What it means in practice. London: BP, 1994.

21. Equal opportunities policy. London: British Gas, 24 December 1993.

22. Leiff S, Aitkenhead M. Assessing equal opportunities policies. Personnel Review 1989; 18(1), 27–34.

23. Torrington D, Hall L. Personnel management: HRM in action. 3rd edition. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall, 1995.

9.7 Further reading

Cassidy J. But not for the author who took on the feminists. 9 January 1994 Sunday Times News Review Section 4, p. 3.

Coussey M, Jackson H. Making equal opportunities work. London: Pitman, 1991.

CRE Case Study No. 1. London: HMSO, 1996.

CRE. Diversity & Racial Equality. London: CRE, 1996.

CRE. Racial equality means business: a standard for racial equality for employers. London: CRE, 1995.

CRE. The Inequality Gap. London: EOC, 1995.

Equal Opportunities Commission. Challenging inequalities between women and men: twenty years of progress 1976–1996. London: EOC, 1996.

Hawkins K. Taking action on harassment. Personnel Management March 1994, 26–29.

Janner G. Sex and ethnic monitoring, discriminating and equal pay. Croner: Surrey, 1984.

Leighton P. Dignity at work. Human Resources Journal Summer 1993, 106–109.

Little A. New disability legislation will affect all employers. Hospitality Oct./Nov. 1996.

McGoldrick A. Equal treatment in occupational pension schemes. Research Report. London: EOC, 1984.

Pye M. The War Between the Sexes. The Telegraph Magazine, 15 October 1995, 15–21.

Shaw M. Achieving equality of treatment and opportunity in the workplace. In Harrison R ed. Human Resource Management. London: Addison Wesley, 1993.

Sullivan A. The witch hunt is ending, Sunday Times 9 Jan 1994, News Review Section 4, 2.

Williams A. Croner’s Guide to Discrimination. Croner: Surrey, 1995.