8

Defining EI

Johann smiled as he watched Debra take a number of sheets of paper out of her bag.

“This is what I came up with when I sat down to think about what it takes to do well in the matrix. And then I Googled it for a while and there didn't seem to be anything hugely important that I had missed. What do you think?” She offered the papers to Johann.

“It's great to see you've put so much thought and work into it. Before I look at the list, let me ask you a couple of questions.”

Debra nodded.

“OK. The first question is ‘if you could do all of the things on your list perfectly would it solve all the issues created or exacerbated by working in a matrix?’”

Debra laughed. “I think it would solve most problems in the world! Seriously, let me look back at what we said the main problems were for people working in a matrix. We said that people in a matrix work across functions and geographies, with people with different values, attitudes and expectations. This means that communication can be difficult even if there is an apparently shared language. They often suffer from information overload as they are peripherally involved in a very high number of projects or initiatives and struggle to manage their time. As a result, their ‘day job’ suffers. Sometimes they have conflicting or what seem like completely contradictory objectives and targets. Decisions can take months to get approved as ‘everyone’ needs to consulted. As a result some people go maverick and play only by their own rules – which they'll probably get away with for a while as there may be confusion over who they are accountable to.”

Johann grimaced, “succinctly put!”

“So yes, maybe. If I could, in some parallel universe, do all of the things on this enormous list, then I would probably be able to get over most of these problems.”

Johann pushed further, “And would it allow you to take advantage of all the potential in the matrix?”

“You mean the chance to work on different projects with people from different backgrounds so that you have a wider network and so the ability to learn, progress and move – by function or geography for example? To be able to use the diverse experience and knowledge so that we get to the best possible solution? To be a clever Lego® piece who uses the flexibility of being able to do different things with different people so that I am aware of new opportunities and so that people think of me for these projects? To get to hear different points of views and expertise and use them to serve the client better so that we're all more successful? Yes,” Debra admitted, “I think that I could really master the matrix if I could do the things on my list.”

“OK. So, to sum up, we've identified the pros and cons of the matrix and noted down some things that people do to become successful in the matrix. Now we need to decide which ones you would like to work on.” Johann paused again. “So which of these would you like to work on first?”

Debra looked down the list. Although she knew exactly what she should be working on – she had identified it as she wrote it down – she wasn't sure she should say it. Noticing her hesitation, Johann made it easier for her by asking a closed question.

“Do you know which one it is?”

“Yes,” Debra admitted.

“What is it?”

“I don't want to say.” The words escaped from Debra's mouth.

“OK. You don't have to say.” Johann paused. “Why don't you want to say?”

“It feels very ‘fuzzy’ and self-indulgent. And I don't want to make you think that I'm either of those things.”

Johann smiled again. “Would it help if I told you what I was working on with my coach at the moment?”

Debra was surprised to hear Johann had a coach. Clearly he really did buy into this development thing.

“We're working on my ability to prioritize – I've found myself overwhelmed as I've taken on new projects and I'm trying to get a handle on things. I've worked out that the criteria I used in the past don't work anymore, and I'm trying to come up with a new set.”

“I want to work on being more open about my own needs.” Debra spoke quickly.

“It seems like you've just made the first step!” They both laughed.

“The thing is,” Debra continued, “everybody goes on about team work all the time and I want to be a team player – of course I do. I want to play nicely with others but I don't want to be a doormat. I'm fed up of working late because someone else didn't do what they should or seeing someone ruin a presentation I worked hard on. And they still get a good review and bonus and promotions.”

“OK, well, leaving aside for the moment the whole question of teams and whether or not the current obsession with them is useful, let's try and focus on the real issue here. What are you trying to achieve? And remember it needs to be something specific so that we know if we've achieved it.”

“I want to get better at saying what I want.”

“Can you be more specific? Think about situations in which you don't say what you want and tell me what you want to change. Can you think of something that happened fairly recently maybe? Do you remember the details?”

“Well, actually, there was something this week. I have a colleague who is constantly late with reports. She always has a great excuse. But that's the point – she always has a great excuse. And it means I can't plan my own day with any kind of certainty.”

“And you haven't spoken up? She doesn't know this?”

“She should know. It's obvious, isn't it?”

“Maybe. Although if it were obvious that would make her someone completely uncaring. Is she that person? In every situation?”

“Well, no. Not in every situation. In fact she was lovely to me when I first joined.”

“What impact is her behaviour having on you?”

“It's stressing me out. And I try not to work with her now which is a shame because she'd be perfect for a project I want to run.”

“So why don't you talk to her?”

“What's the point? She probably won't stop!”

“Well maybe not. But she certainly won't if you don't tell her, will she? Look, it's like this. Imagine you had a puppy and it peed in the corner…”

Debra looked at Johann, surprised. “OK” she said uncertainly.

“Bear with me. The first time the puppy pees it doesn't know any better, right?”

“Right.”

“So, if you don't want the puppy to pee in the corner, you have to teach it that it's wrong, right?”

“Right.”

“And if you don't teach the puppy then it's not the puppy's fault it misbehaves in the future, it's yours! Right?”

“Right.”

Debra seemed to be following but Johann wanted to be sure. “What I'm saying is that your colleague is the puppy and you are not stopping her from peeing in the corner!”

Debra burst out laughing. “OK,” Johann was laughing too. “Of course, I don't mean that she's a puppy or that you should train her like a puppy. I just mean that if you don't have the conversation nothing will change.”

“OK, fair enough,” Debra agreed. “But I don't know where to begin.”

“Ah, well, that's a different problem,” said Johann. “And I can help you with that. Here's a great book. Have a read of this and we can discuss it and use it to plan your conversation at our next meeting. OK?”

Debra took the copy of Crucial Conversations and, scanning the back briefly, put it in her bag and returned her attention to Johann.

“So,” he said, “we talked about what you wanted to achieve and, in essence, it's about having the tools to have difficult conversations so that you can speak up without ruining relationships. As a first step towards getting there, you're going to read Crucial Conversations before our next session so we can then use it, if you want, to plan your conversation with the annoying colleague. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” said Debra, wondering how she was going to fit this in on top of all the real work she had to do. Well, she could always just skim it.

“Is there anything that might stop you doing this? Do you have enough time? I don't want you to commit to something you can't do.” Johann fell silent.

Debra looked at him. How had he known? “No,” she said, “I'll read it and I'll be prepared. Thanks for the book.”

“No problem.” Johann crossed his arms. “So, we've looked at one thing on the list. You seemed to have a lot on there?”

Debra looked down at the sheets. “Yes, way more than is practical really. And, even more worrying, it all seems a bit, I don't know, ‘nebulous,’ is that the word? I mean, I've written that people who are good in a matrix are good at communicating. OK, fine. So what? I mean, how does it help me to know that? I suppose I could go on a communications skills course but, really, at this stage in my career? If I don't know by now how to look people in the eye and adjust my tone of voice then I doubt being told to do so by some over-priced trainer in a nice hotel whilst my real work piles up is going to help.”

Johann was delighted that Debra was being so honest and straightforward – it made his life so much easier and, of course, it wasn't always the case with mentees. Or anyone for that matter.

“OK, well I can see how it's a bit overwhelming. In all honesty, I think that's why we tend to let the ‘soft’ stuff go – there's a lot of it and we don't seem to be very good at helping people to get better at it. That's why I think the idea of emotional intelligence is useful. It kind of provides a ‘peg’ on which all the different skills can be hung.”

Debra didn't snort. She knew that wouldn't go down well and, although Johann talked about ‘soft’ skills, she definitely didn't want him to feel any disrespect from her as she wasn't sure that she wanted to be on his wrong side – he had a tendency to say things straight out that could be disconcerting.

And he asked good questions. In fact, he may have just asked one now. Debra pulled her attention back to the small room she was sitting in with Johann, who was looking at her expectantly. She shook her head. “Sorry, I was miles away. Can you repeat the question?”

Johann tried not to be irritated. “I asked if you felt whether you have a clear understanding of what is meant by EI or emotional intelligence?”

Debra considered: she had read all the articles Johann had sent her and she was sure that she could recognize someone who was emotionally intelligent but she didn't really have a definition. “No,” she admitted, “I suppose I don't.”

“I suppose it's no wonder we have such trouble selling the idea,” Johann mused, “given nobody seems able to define it.”

“That'll do for a start,” thought Debra as she considered all the other objections she had to the idea of emotional intelligence.

“But, of course, there are a couple of definitions that are fairly well established and agreed. Having said that, I'm not sure that knowing a definition is as useful as getting the concept and living it – I remember a company I heard about that wanted to instil a culture where everyone spoke up. The way they did this was by putting everyone through training so that they could all define culture and identify cultural levers. It went really well – everybody could give the definition and tell you the seven levers or whatever. Unfortunately they never did anything with those levers or the definition so the whole thing kind of died a death.” Johann stopped talking.

“OK,” said Debra, a little irritated herself now that Johann had started off on his talking horse again. “But it would be useful to see it defined and to use,” she stressed the word, “that definition when we're talking.”

“Fair enough.” Johann fired up his computer. “I'll just be a minute,” he said as he looked for the relevant file. Debra sat back and looked around his office. Noticing a picture of Johann and a very pretty blonde woman with two kids she asked, “is that your family?”. “Yes,” he replied, distracted, “my wife and our two grandchildren.” Debra silently congratulated herself on not asking him if it was his daughter.

“Ah, there it is.” Johann was triumphant. “According to my notes, Salovey and Mayer revised their initial definition of EI to: “The ability to perceive emotion, integrate emotion to facilitate thought, understand emotions and to regulate emotions to promote personal growth.”

He stood up and wrote it on the whiteboard that covered almost all of one wall. “I'm not sure why they revised it – the old one seemed OK, and pretty much the same thing – academics! But what I like about it is that it is so simple. It says that emotional intelligence is about being able to sense emotions and understand them so that we can use them when they're useful and manage them when they're not. What do you think?”

Debra thought it was a perfectly reasonable definition of emotional intelligence but she didn't know what she was supposed to do with it or how it helped her and she said this.

“Look, it's about behaviour really. What they're all saying is that our emotions impact our behaviour and so we need to be able to manage these if we're to manage our behaviour and get what we want.

And of course that other people's behaviour is motivated by their emotions and we need to be able to decode these, and help them to do so too, if we want to change their behaviour.”

“That seems manipulative,” thought Debra.

As if he'd heard her thoughts, Johann carried on. “Note that phrase ‘help them do so too’ – the idea is to use this for good although, like with any tool, people can use it to be manipulative. But I don't know what to tell you – that's true of everything, isn't it?” He shrugged his shoulders.

“Look, there's a lot of research out there (Goleman, Boyatzis and McKee's book springs to mind) that suggests that the ‘leader's mood is quite literally contagious, spreading quickly and inexorably throughout the business’. They say that, because the brain's emotional centre, the limbic system, is an ‘open-loop system’ (it relies on external sources to maintain itself), then we rely on our connections with others to decide our moods. If our moods can affect others and theirs can affect ours then surely knowing that must be useful?” Johann stopped talking so that Debra could respond.

“OK, so emotional intelligence is about recognizing and using emotions so that we can manage our behaviour but there's got to be more to it than that?”

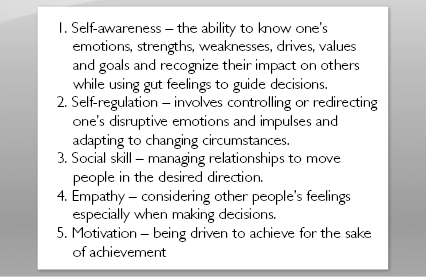

“Well, yes and no, I mean, Goleman's model looks at five different aspects of EI.” He showed Debra a slide.

“That doesn't seem too far away from what the academics came up with? There's also an ability-based model done by Mayer and Salovey but I don't have much trouble seeing the similarities here too. This one looks at four types of abilities.” He showed another slide on his screen. “Although, of course, the Goleman model talks about abilities underneath the five aspects I showed you before.”

He paused. “This model sees emotions as information that helps you to make sense of the environment. And suggests that we vary in our ability to process this information and connect it to other things. That strikes me as true. What do you think?”

Debra considered. “So what they're saying is that EI isn't about character or personality traits, for example shyness or extroversion or even about particular talents, for example being great at golf. Instead it's about a mental skill set – it might come more or less naturally but we all have the same ‘number of dots’ – we're just more or less practised at connecting them and then doing something with the picture.”

“Exactly. Great analogy. It's about being able to figure out your own emotions and those of others, and then doing something useful with that information versus being sociable or warm or mean or nasty. And, even assuming you notice the ‘dots,’ that is the emotions, understanding the picture you've drawn with those dots can be hard – especially if that picture is different from something we're used to seeing. Like when we're working across cultures or if there is some other thing that makes it harder to understand someone else's picture, for example the experience of being a different sex or race.” Johann looked at Debra for confirmation that she understood what he was trying to say.

“So, although the emotion may be universal (everyone gets happy or scared or angry) the triggers might be different and so too might be the way those emotions manifest themselves? Hmmm, suddenly, recognizing emotions is harder than it first seems.” Debra admitted.

“Right,” Johann continued, “because not only do you have to be aware that other people are having emotions, be convinced you need to look out for them and be skilled at noticing them even with the ‘noise’ in the signals, you also have to be monitoring your own emotions and behaviours and all of this is in constant interaction whilst you simultaneously carry on a conversation about, for example, where to allocate resources in the budget.”

Debra smiled. “Or something important?”

Johann didn't miss a beat. “You'd think, right? Given all the actually important things on our collective plate that we would all be wonderfully focused so that our personal and, some might say, petty emotions wouldn't get a look in but, of course, when it's important our emotions are clearly going to be involved. Having said that, some of the most emotional debates I've ever seen have been around the allocation of car park spaces!”

“So, if emotions lead to behaviour then why do we pretend that emotions aren't important at work?” Debra asked. She was genuinely interested to hear Johann's insights – especially about colleagues at his level.

Johann shrugged. “I've asked myself this a lot. I don't think it's because we don't care or don't believe it. I mean, these are intelligent people who know that emotions lead to behaviour. One of my colleagues said to me the other day, ‘you know it's weird – we accept in the movies and novels that emotions lead to behaviours and behaviours lead to results – why would we think it's any different in organizations?’ And she was right – organizations are about getting results. But if we just focus on the results nothing changes – we need to go to the source of results – behaviour – and even beyond that to what leads to behaviour – emotions! And emotions are tricky because, although we all have them, they may, as you say, be triggered by different things and be expressed in different ways depending on a variety of factors. Your experience leads to your understanding of your emotions and those of other people. To return to the movie analogy – we understand that movie characters have different reactions to events than we would have because they've had different experiences but we forget that in the workplace and treat everybody as though they are the same as us.

“For me it's very simple. I want as much information as possible when making decisions – in any part of my life. My emotions and their impact on my behaviour are part of that information and so are the emotions and so behaviours of the people I interact with. I'm not perfect but I am getting better at noticing the first step. And I know what questions to ask now.

“Emotional intelligence isn't about having the ‘right’ emotions or dictating behaviour but rather being aware of and thinking about what emotions are going on, why, the impact the emotions might have and what you're going to do about it.

“For example, I had a new CEO earlier in my career – he had taken over from a particularly well-loved leader under somewhat dubious circumstances. Rather than just carrying on he made sure to acknowledge the emotions and deal with them upfront – I reckon he saved himself (and us) six months of gossip and political manoeuvring!

“But, often, there is an element of ‘I didn't get to where I am today’. The guys at the top either didn't need help to become emotionally intelligent because they were naturally good at this stuff. As a result they don't see the need for helping others, or they don't think a training course will work for whatever reason. Or maybe they don't see the need for emotional intelligence because in the world they worked in it was less necessary. Sometimes they hold all of these views at the same time. For example, they say things like ‘our people should know this stuff already – it's basic’ and ‘I don't think you can teach this stuff – it's too hard’. Amazing!

“Deep down I think it's a lack of understanding – they haven't had the chance to observe people with high emotional intelligence. And, of course, you can ignore it and you may very well succeed anyway – perhaps you are indispensable in some way – but your career journey will certainly take longer and be more stressful for you and the people around you.”

Johann realized he'd been talking for a long time. “And on that note we're out of time.” He stood up. “Don't forget to read the book and come prepared to practise the conversation with your tardy colleague. Plus, we can always talk more about emotional intelligence if you want.”

With her mentor's words still ringing in her ears and her head still somewhat confused by this sudden trend to talk about emotions the whole time, Debra left the room. If emotions are so important why didn't we learn about this stuff in school?