13

Fake It Until You Make It

Debra was excited: “You've been using EI on me all along and teaching me to use it even whilst I was learning about it.” It was almost an accusation.

“That's true.” Johann responded mildly. He had been expecting this. In fact, he was surprised it had taken so long.

“Why didn't you tell me?”

“What would have been the point?” he asked gently. “You didn't believe in EI or see any use for it in business in general and the matrix in particular. So instead of telling you what I was doing I just did it and waited for you to figure it out yourself. But, remember, I did say that I'd be transparent and I will. It just wasn't the right time before now.”

Debra smiled. “So go on … ,” she challenged.

“What, you want me to reveal my secrets?” Johann pretended to be shocked. “Actually I do have a list.”

“Of secrets?” Debra's sarcasm was apparent.

“Well, yes. I mean, they're not secrets but I think they are the ‘secret to EI’. I'm working on the ‘fake it until you make it’ principle here but it seems to work or at least it did for me. Years back I had a mentor – I didn't call him that of course – and he was always able to get great results from the people around him even when they didn't work for him. People opened up to him and trusted him. Everybody liked this guy so, over the years, I started to note down the things he did, and mimicked them. I didn't really understand why. Then, I added to the list when I saw other people do things that seemed to help them. When I started looking into EI I realized that my list was pretty much a set of tools to help you ‘fake’ EI or, to put it another way, to practise in a way that helps you get better at it.

“It's a very practical list. Basically what I tried to do was break down what people did – their practice or skill if you like – into the smallest possible units of behaviour. I've called them the tools. Then all I had to do was use those tools a lot. Over time I got better at using most of them and in some of them I'm really good now. I still struggle with others.”

So he's on different rungs of the ladder with the different tools, Debra thought. “What do you mean you broke the skills into tools?” she asked.

“Well, let's take presenting as an example. Presenting is a skill and my test for this is: ‘if someone tells you to get better at this, can you do it without more information?’. Like, someone says, ‘Debra, you need to work on your presentation skills’. How useful is that?”

“Not very.”

“Exactly. So we don't teach presentation skills or EI. Not if we want to do it properly. We break down what makes a good presenter – what do they do? And what does someone with high EI do? Because we can do something useful with that. We can teach that. And those tools are multi-purpose – they can be used to help you do lots of different things.”

“I see,” Debra said. “Can you give me an example?” If not quite on the edge of her seat, Debra was certainly interested.

“Take misaligned goals as an example. How much time and energy do you think is wasted in the average organization because of misaligned goals?”

Debra assumed this was a rhetorical question.

“If you read up about EI you'll be told that having high EI helps with dealing with misaligned goals. You'll learn that emotionally intelligent individuals manage their emotions well when goals are discussed. They know it's normal to feel frustration and stress when goals are misaligned, and they have the ability to manage their frustration and stress and prevent these emotions from rising to the point that their discussions become unproductive. They can predict the stress the misaligned goals will cause to themselves and others and so raise their concerns in advance. And they can communicate their concerns so that people respond favourably. This is all very well. But it doesn't tell you what to do!

“Training will tell you what to do of course. If you do training in EI you'll learn that it's important to, for example, listen or find mutual cause. But the only way you'll actually get better at doing those things, to dealing with misaligned goals is if you actually use these tools.” Johann seemed surprised at the audacity of his own claims.

“So you're saying that the things on this list are like a magic bullet?”

“No. I'm saying that they're all highly gifted bullets. None of them alone can do everything although each one in itself is powerful; but together they're much more powerful than when used separately.”

“Can't wait to hear them,” Debra deadpanned.

Johann leaned back and, counting with his fingers counted off:

“Seems like some of these at least can be understood in more than one way?” Debra enquired.

“Absolutely, but that's OK. It doesn't have to be detailed. Think of it as an aide memoire, something you can refer back to when explaining things to other people. And this way you see the tools as being multipurpose. You only have 14 things to remember to get better at. And you can tell if you're doing them or not.

“Only 14?”

“No, you're right. There's 15! Last but not least there is the one that is both the easiest and the hardest:

“I'm surprised that listening isn't on the list?” Debra asked.

Johann was agitated. “But it is on the list. What do you think listening is? ‘Reflect what you notice,’ ‘Acknowledge what you hear,’ ‘Check for confirmation’ and so on – I would argue if you can do all of the things I just said on the list, you'd be a pretty good listener!

“The idea is to break things down so that you or somebody else can SEE or HEAR you do the behaviour/use the tool. That way it's a mechanical thing. Almost anyone can remember to check for confirmation – it's not hard. But few people know how to get better at listening. This set of tools is supposed to be really practical.

“It's like professional golfers. They might be working on 100 things with their coach, but they won't try to change all of these during the act of playing an important round. They'll step on the tee of a competition focusing on doing one thing better. Play 18 holes, take stock, monitor improvement. They go off and work on all aspects again with the coach, then back to the course for another competitive round – with just one ‘swing thought’ in their heads. They might use the same thought again the next round, or they might move on to another aspect. They're always working on changes, but in bite-sized pieces to affect measurable change.

“We need to break things down into bite-sized pieces that we can work on.”

“But some of these will depend on others. Like if one tool isn't working properly then the others will not work at full capacity either.”

“True enough,” Johann admitted. “But, and this is the rub, you can probably only work on one or maybe two things at a time if you're going to do it properly. Three at a real push. And even if it's only one then at least you're getting better at one thing. When you've done that you can start on the next. I mean, what are your other options? Give up?”

“OK. Can you give me some examples of these tools at work?”

“Sure. Research has found that decisions in matrix organizations are more untimely and can be of lower quality than in traditional forms of organization, although, of course, better decision making should be part of the advantages of the matrix. Emotionally intelligent individuals recognize that some emotions are likely and look out for them. When they think they spot them they confirm the emotion and its source and, the emotion out there and acknowledged, they then choose how to behave from the various options open to them. For example, they might work to defuse any anger because they know that the research suggests it leads people to make snap judgements – they do not consider the available information and the possible consequences. Or they might increase anxiety to influence more thorough processing of information or induce happiness for more creativity.

“Can you make the connection? Between what I've just described and the tools on the list?”

Debra looked at the notes she had scribbled as Johann listed the 15 tools.

“Yes, they would have to use all of them. Even 15. ‘Do what you say you will do’ but that is pretty much the case in every situation.”

“How do you make out that they'd have to review regularly?”

“Well, they must review the business literature regularly to know about the research you described.”

“Good point! I'll have to add that interpretation to the master list.”

Debra was intrigued to see this master list but did not, yet, ask Johann for it. “I still don't see how you teach this though? I mean, beyond a certain level.”

“That's true. But it's probably true of most skills. I mean, once you've learned the basics of riding a bike, how do you teach somebody to get better?”

“I suppose it depends. Once you get past the basics. Yes, and so training in EI focuses on the basics, and, if you're lucky, you'll get a chance to use some of the tools although probably not in a way that makes it clear that you can use each of them in lots of different ways. But to get really good, what do you need to do? How can you teach somebody to get really good at EI?”

“Well, I'm not sure,” Johann admitted. “But I think it's mostly about being an example (like the guy I learned from), then, after that, you can be transparent about the tools you're using and after that it'll probably depend on the individual. The ‘teacher’ needs to have high EI and try different things, notice what happens and then make adjustments. After the basics you don't really teach; you help the other person to learn. But I suppose there are a few tools to add to the list that could be especially useful to ‘teachers’.”

“Like what?” Debra asked.

“I'm still learning about this so the list is changing more. Let me find it.” Johann opened his desk drawer. “I've added:

He explained. “Like ‘say more about X’ or ‘anything else?’ because you're human and your concentration will slip at times and you won't know what they were talking about. And because sometimes simple questions are the best. The three questions to deal with the three ‘clever stories’ of victims, villains and helplessness are a great example of a stock question that you can use a lot.

Debra nodded.

“I didn't have to ask too many questions or try too hard with you as you opened up. But you can always get better at asking questions – both to yourself and others. They're useful in so many ways that this tool should probably be some kind of mega tool. A power tool! So we now have 15 tools and a power tool! One that you can use in many ways – to get clarity, to confirm, to probe, to doubt, to get details so you can build understanding and then empathy.

“But the most important thing another person can do is help you to practise – to work through in slow time – like we did, in advance. We're creatures of habit and practising helps us build good ones. And helps us feel confident enough to try things in real life.

“But, look, no teacher is going to be perfect. That ‘ladder of learning’ we talked about has more than four rungs. The fifth rung is reflective ability, or ‘conscious competence of unconscious incompetence’ and that leads you to noticing where you can still improve so you slip back to the third rung for a time. Which is good because that's how you stay sharp.”

You're sharp but not the tool? Debra thought. “How do you use the detailed list?” she said aloud.

“Well, now I know it by heart of course. Although I still read it before big deal meetings and look at it once a week. And I ask myself what I should add or take away. I don't want to let it get too big as it stops being useful I think. Once a quarter I choose one of the tools and ask someone to observe me just using that and to give me feedback. I force myself to become more aware of that tool and my use of it and I sometimes tell people what I'm working on and ask for their help.

“The thing is – it's not complicated but it does take commitment.

“What you're trying to do is help someone to move up the rungs from unconscious incompetence to conscious competence. You start where they are and you help them but it's their responsibility to do the work.

“As they get better you point out what they're doing well and give them a heads up on what is stopping them from getting to the next level. Like when a kid learns to walk – eventually they get really good at it and run and then they get good at that. But to be a professional runner you need to deconstruct your run before you can reconstruct it. A coach can help but the work is up to the runner. It's up to them to practise and the coach or mentor or whoever can help by asking them to reflect and by questioning their thinking and their actions in a useful way.

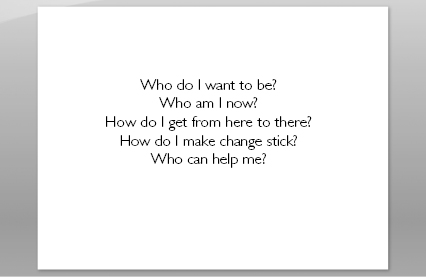

“Another way I can help is through what Goleman, Boyatzis and McKee call ‘a journey of self-discovery and personal reinvention’. They suggest asking a number of questions. Some might find the questions a bit, um ‘American?’ if you know what I mean?”

Debra nodded. “What are they?” Johann found the slide and flashed it on the screen.

“I know,” he said, anticipating Debra's response. “But imagine if you were able to stop yourself in the middle of a flash of anger and answer those questions before you reacted. Just like in the Crucial Conversations book. That would be useful, right?”

Debra agreed. “Obviously.”

“Well, the only way to do that is to get to Level 4 on the use of those tools – to be aware that that is what you should be doing and noticing when you do and don't do it, and noting the results and then doing it more and more and better and better until you do it without noticing!”

“Or I achieve Nirvana! It does seem like a lot of work?” Debra suggested.

“Well, yes.” Johann didn't seem to have any problem with that. “You don't think your way into a different way of acting; you act your way into a different way of thinking. So many people I talk to want there to be a different answer. There isn't. It's like that training course you mentioned that you went on and liked – The Leadership Challenge? You have to do things differently and that involves pain and heartache sometimes and embarrassment and boredom at other times. But it's worth it because, eventually, it's less exhausting as you're being truly authentic.

“You have no choice but to be authentic because you need to be trusted. You are not only allowed to have a point of view and to state it, you're almost obliged to because you have the tools to do it in a way that will help the situation you find yourself in. So you know your stances on major work issues and are open and willing to engage in conversations about them. This is important because if others are to trust you they need and want to know where you stand – they don't want to have to guess or be blindsided midstream.

“And you can be transparent. EI helps you to understand the difference between navigating the political waters of your organization and actually becoming the politics itself – how to get support for your initiatives but be clear about what you are doing, why you are doing it, and how you are doing it. With high EI you can communicate this to people in a way that they can understand and hear you.”

“That does sound worth it.” Debra was amused that Johann was still selling the concept to her.

“Of course it is.” Johann was in evangelical mode. “These tools are the only game in town.”

Debra now felt that there should be more to it. Just using 15 tools and thinking and reflecting on how it went so you get better? And then practising again? Well, she reflected, I suppose it worked for sports stars and musicians and dancers. All I'm really doing is practising a behaviour – just like them, she thought.

Once again Johann seemed to show an uncanny ability to read her mind. “It's like Andy Murray or someone like that.” He stopped to check that she got the reference. “He's clearly got an in-born talent.”

“True. But it doesn't have to be someone with that job description. If you want to give yourself every chance to succeed in changing your behaviour – something that is notoriously difficult to do – just ask any smoker or coffee drinker. Weirdly, they also say that it's just as important to keep seeing that person when things are going well as during times of stress. Soaring cortisol levels and an added hard kick of adrenaline can paralyse the mind's critical abilities, so people fall back into old habits during these times.

“According to Goleman, leaders can improve their emotional intelligence if they are given:

- Information – candid assessment of their strengths and limitations from people they can trust.

- Guidance – a specific development plan using ‘naturally occurring’ workplace encounters as the laboratory for learning.

- Support – someone to talk to as they practise how to handle different situations.”

“That makes sense to me – you could be describing the job of a great manager or coach or mentor.”

“And, because the research suggests that people will vary on how proficient they are at different parts of EI, a generic training course probably won't be much use. For example, some people could be worse at identifying how others feel while others are less adept at managing emotions. So you need one-to-one help to make sure you get the right intervention at the right time and you will certainly need different people at different parts of your career.”

“The way you say it seems to take away from what you do – are you really saying anyone could help me?” Debra asked.

“Well, yes and no. I mean it doesn't have to be someone older and wiser and more senior. But it does have to be someone who practices what they preach. These tools aren't hard to use but it takes time to develop the right skill set and, as we discussed before, many people don't take the necessary time.

“There's a story of an external executive coach who was asked by a CEO to work with the CFO. ‘Please help me,’ the CEO said. ‘I can't get this guy to do anything I want!’. ‘What do you want him to do?’ asked the coach, writing down the answer the CEO gave. The coach then met the CFO and asked him what issue he would like to address. ‘My biggest problem,’ the CFO said, ‘is that I just don't know what this guy wants from me’. The coach asked him if it would be helpful to have a list and, when the CFO agrees, shares it with the CEO. Six weeks later all is peace and productivity with the CFO, so the CEO asks the coach to come in for a meeting. ‘You're a genius,’ said the CEO. ‘How did you do it?’. When the coach explained, the CEO got angry. He felt he'd been tricked. ‘Anybody could have done that,’ he said. The coach was forced to explain, gently, that that was true. But nobody had.”

Debra laughed. “Maybe if the coach had had higher EI he might have anticipated that reaction!”

“Good point,” Johann laughed too.

“So yes, it could be anybody who uses the tools, but like an actor who wants to teach other actors, he'd better be able to explain the process. The coach or mentor needs to have that ‘Rung 5’ level of self-awareness.

“But don't forget, it's about the coachee or mentee or student or whatever you want to call them too – they have to listen and take responsibility for change!

“One thing I forgot to say about how having a mentor or coach is that they should focus you on that responsibility. Their objective is to help you to act in whatever way you've decided will help you. They'll need to understand how to manage your emotions, so that you can eventually do that as well. Your job is to do the work, to try the behaviours. They can help by getting you to focus on potential obstacles and asking great questions. They can make sure you have SMART actions, but as Goleman et al. say: ‘the only way to develop your social circuitry effectively is to undertake the hard work of changing your behaviour’.”

“OK. I'm convinced. And delighted I have a mentor.”

Johann bowed.

“But it must cost a fortune? I mean the basic training alone is expensive and then the coach or mentor. You're not cheap, I assume?”

“Oh yes, it all adds up,” Johann admitted. “And we don't even track the expense of people not being at their day jobs because they are attending training or coaching. And for the mentoring or coaching we often don't have enough internal people who are willing and able so we use external suppliers. So yes, it costs. But we need it.

“We need employees who are able to deal with the challenges of the matrix; who can better align various goals, clarify roles and responsibilities, make timely and quality decisions. We need to see results across silos through communication and cooperation. We need people who can build strong bonds because we need those for practical as well as emotional reasons. Those aren't things you learn in one day or even a five-day training session. It takes more time, patience and practice than that.

“Let's imagine a typical matrix situation. There is tension between the function and the geography about a decision – let's say it's a marketing campaign. The ambiguity inherent in the matrix leads to tension and anxiety among employees as they try to reconcile unclear roles and responsibilities. Now, a key tenet of the matrix design is that tension is inherent and desirable. But research shows that employees who are unaccustomed to the tension and don't have the tools to deal with it spend immense time and energy unsuccessfully trying to reduce it. Often senior management don't notice, or they don't care, suggesting foolishly that ‘the tension is built in, live with it’.

“Emotionally intelligent employees are more likely to perceive the tension and its effects, understand the specific issues that are causing the tension, and then facilitate solutions. Those with very high EI are, I bet, able to educate others and help them understand where the tension comes from and strategies for dealing with it.

“Notice that none of the tools are exclusively for use with peers or direct reports. These tools and EI work when you are ‘managing up’ as well. You need to manage up and across not just when you have a difficult boss, an incompetent colleague or an important project. You need to manage up and across, for example, to get the production guys to see that your project will help them meet their goals; to establish authority so you are trusted with new projects; to get volunteers. Managing up is about understanding your boss's priorities, pressures and work style. And you can't do that without EI.

“There are times when individuals, especially those who want to advance very quickly, may become manipulative and try to game the matrix. Because they have different reporting lines, they can play people off in the organization and nobody holds them accountable because it's not clear whose job is whose. You might see someone who appears to be cooperative, but in the background they are motivated to achieve something different which will get them rewarded. You need EI to be able to be vocal, to communicate openly with people in a way that makes it likely they will listen.

“EI can be used in the strangest settings. It seems some bill collectors were trained to express calmness when talking to angry debtors and anger when talking to friendly or sad debtors so as to increase the likelihood that they received payments. Obviously this involved all the different aspects of EI. I wonder how they were trained?”

“They would certainly have been motivated!” Debra pointed out.

“Yes, sales people often seem interested in this. I suppose for the same reason – they see an immediate connection and link to their back pocket, but the rest of us have to look a little harder to see the need to build better relationships. We think that doing our job should be enough. Apparently women are particularly bad at this.” Johann was aware, as a mentor, of the danger of not acknowledging experiences different from his and so had looked into this area. “As I understand it women are likely to not speak up, hiding their light under a bushel. I suppose we've already talked about you in this respect?”

Debra agreed. “And yet we think of women as having higher EI than men usually.”

“Hmmm, interesting point. Maybe women, in general, tend to be better at some things, for example noticing emotions. But this doesn't mean they're good at all parts of EI.

“Anyway, remember the cost of having someone with low EI – the damage they can do to themselves, others and the business in terms of time wasted and absent conversations. It seems to me that we don't have a choice. Either we put the work in and improve our EI, or we accept the frustrations that come with trying to work in a matrix without those tools. Complaining about it will only eventually irritate your co-workers, friends and family. And it won't change a thing.”

Debra nodded her agreement as Johann continued.

“But yes, you're right. It's expensive and takes times and effort to do this right and, if you're using internal people – even senior managers like me – you have to make sure those mentors are properly trained. There is no reason to think that they have the necessary skills.”

“One last thought – it's OK to have training and a mentor/coach, but what about your manager and their manager?”

“Great question. Now you know how this works you won't be surprised that I'm going to suggest that you consider the answer to this for the next session. What have you seen that worked in the past? What would work for you?”

With that, Johann brought the session to an end and Debra gathered her belongings and left the room.