Chapter 5

Be Flexible: When Letting Them Have It Their Way Makes Sense

Flexing with the Autonomous

I kissed a lot of butts to get where I am today, and now it's time for someone to kiss mine.

—A consulting team manager

I told them that I could only work three times a week, and they scheduled me five times a week…This has happened to me twice. So, I ended up quitting.

—A Millennial

We want to have a say about when we work and how we do our work.

—A Millennial

All things being equal, when there is a choice between getting your way and going their way, go their way. The idea that leaders and managers are going to change members of the current generation into what they want them to be is a strategy destined for failure. Only by flexing with the concerns of Millennials will today's managerial leaders have opportunity to develop the trust and rapport required to lead them.

The Millennial Intrinsic Value: Work-Life Blending

Work-life blending is one of the most celebrated values of the Millennial generation. They work to live—not live to work. They don't mind accessing work during their personal time, but they want to access their personal life during work. They want time for friends, family, and doing the things they enjoy. It does not mean that they are lazy. It does not mean that they do not want to work. They want work that is meaningful. They want work that is challenging. And they want it on their terms. They do not necessarily wish to forego upward mobility or opportunity for advancement but at the same time they show little or no reluctance to change companies in an effort to have it all. The fact that many of them are relationally and materially untethered affords them the option of moving back home or cohabitating so they can hold out for the job they want—or the job that gives them what they want.

The intrinsic value of work-life blending leads to a workplace value that Millennials hold—autonomy (see Table 5.1), but not for the reasons you would think. They do not wish to be free of direction or supervision. Rather, giving Millennial employees autonomy on the job communicates that you believe in their ability and trust them. Like other employees, they detest being micromanaged. However, other generations dismiss a micromanager as anal or controlling. Not Millennials. They take micromanaging behavior personally because it connotes a lack of trust or confidence in them. A common refrain heard from Millennials in our study—though not in exactly these words—was, “Show us what you expect us to do, and then get out of our way.”

Table 5.1 Flexing with the Autonomous

| Flexing (Be Flexible) | Autonomous |

| The ability to modify workplace expectations and behavior. It requires empathetic listening and the willingness to adapt to different ways of doing things. | Millennials express a desire to do what they want when they want, have the schedule they want, and not worry about someone micromanaging them. They don't feel they should conform to office processes as long as they complete their work. |

Autonomy is not only an intrinsic value of Millennials but also an intrinsic motivator. Many managers have lamented over the futility of trying to put motivation into unmotivated people. The best thing a manager can do is to create an environment in which a person becomes self-motivated or intrinsically motivated. Daniel Pink and others argue that external motivators such as reward and punishment are less effective in today's work environment and can actually be counterproductive. Intrinsic motivation consists of three elements: (1) autonomy, (2) mastery, and (3) purpose.1 Managers who practice flexibility create environments in which people self-motivate.

The Bias of Experience

We can imagine you are thinking to yourself, “I have made sacrifices my whole career to get to where I am, and now you are telling me I need to be more flexible?” Yes, but only when it makes sense.

The lamenting manager we quoted previously may have been more frank than others. However, her sentiment was shared by many of the managers we interviewed. One of the unspoken promises of the workplace is that if you are hardworking and loyal then your day will come after years of patience—you will get to influence your organization the way previous generations of leaders did in their turn. Junior employees will feel obligated to listen to you. You might even get to call the shots outright. Many managers are finding that is not their experience. Quite frankly, there is an unrealized expectation that experience and position should count for something in the eyes of their subordinates. The expectation is there because managers remember their own journey of entering and assimilating into the workforce. We heard comparison after comparison, “I would have never asked for time off having only been on the job for a month.” Or, “He told me he was a volunteer high school coach and needed to leave for practice by 2:30 p.m. every day; I'd love to have seen my old supervisor's face had I told him something like that.” It wasn't that it was hard to say no to some requests; they just resented being put in the position to say no or to be the heavy.

As difficult as it is, you have to suspend the bias of your own experience and not compare yourself to them. It only creates frustration and resentment unless you are using yourself as the bad example (addressed in Chapter 9). A great exercise is to listen to yourself or your colleagues and make a note of when comparisons are being made. It happens more frequently than you think.

Another notable frustration managers experienced stems from the fact that their own effectiveness depends on what they perceive to be an undependable group of workers. They are undependable because there is no certainty they will be here tomorrow. A university vice president illustrates this sentiment:

I started here at $19,000 a year. The job is a big job. It requires a lot of work, but people stayed longer and there wasn't kind of this movement all over the place. Now it just feels like—and not just here but with colleagues at other universities—it's hard for us to keep our staff at those lower levels for longer than a year or year and a half. And that, obviously, has an impact on the staff and on the office as a whole. It impacts our goals and how we accomplish those goals. It makes it hard to do work because you're constantly retraining people, and that takes a lot of time and energy. So when we go through job interviews, we ask each person: can they see themselves here for three years? We don't ask for a signed contract, but we do ask them up front. It's our hope that they would have the intent of staying here three years, and they all say “oh, yes absolutely.” Then at a year, they're usually looking at other options, or even leaving at that point. I think giving your word means something, seems to mean something different now, and most of my staff see that with their Millennial staff they manage, that giving your word doesn't really mean much to most of them.

The university vice president, though frustrated, eventually enumerated several good business arguments for flexing: realizing organizational goals, reducing training expenses, and maximizing time investment. We add a few more: employee recruiting, retention, and the transfer of tacit knowledge.

One of the biggest challenges facing organizations over the next 10 years will be employee procurement. Lately, Wall Street, Detroit, and the medical industry have feared competition from the federal government, but the real competition with the feds will be for young talent. Many organizations have wised up, and they are taking seriously the need to adapt their recruiting messages to the Millennials. One example is Xerox's employee recruiting campaign. The message is that you can be you at Xerox. Notice the subtlety in the online ad, not only can you be you but we affirm you (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Xerox Employee Recruiting Advertisement

Source: www.xeroxcareers.com.

The test for companies will be to live up to their recruiting advertising. Sometimes marketing can get ahead of development and make the mistake of overpromising and underdelivering. Organizations may have the savvy to sell themselves as employers to attract Millennials. But will they have a management team that can keep them?

Psychological Contract

We believe that all of the nine competencies are critical to retention, but flexing in particular affords you the time to build rapport with employees. Flexing is also perceived as a good faith effort to meet Millennials where they are and a willingness to negotiate expectations. In essence, flexing is a visible expression of the psychological contract. Chris Argyris introduced the concept of a psychological contract to address the white space in the employer–employee relationship that does not get addressed by a formal, written contract. The function of the psychological contract is to reduce employee insecurity and build trust. The concept of a psychological contract is more than 50 years old, but never has it been more useful than for understanding what shapes the workplace behavior of Millennial employees. It explains the angst Millennials experience when deciding whether to stay or go. They weigh their obligations to the organization against the obligations of the organization to them. If they sense an imbalance in realized expectations, they do not protest. Why bother getting into an argument with an authority figure who can only tell you how things used to be when she was young when one can just leave? If you haven't noticed, Millennials have a preoccupation with the obligations of management toward them. One manager said it perfectly, “It seems all I hear from them is, ‘What have you done for me lately.’” Expectations are not static. We believe that flexing demonstrates a good faith effort on the part of managers to address the real-time expectations of Millennials. Flexing is the dynamic for an ongoing dialogue and negotiation of expectation. Willingness to be flexible with respect to scheduling, process, and expectations gives Millennials a feeling of influence on what happens to them in the organization.

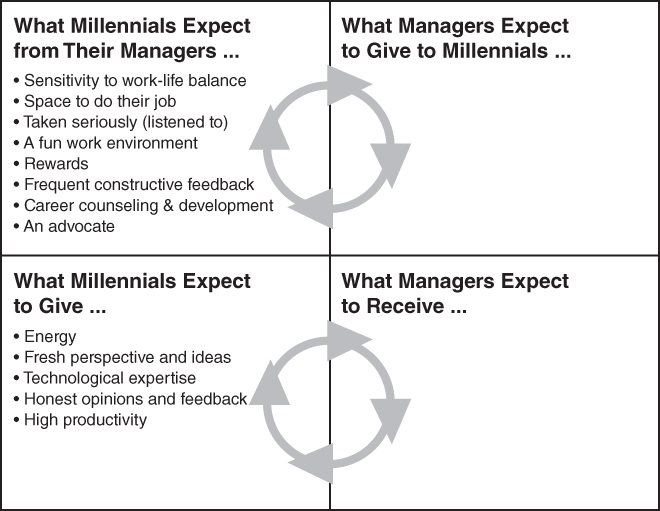

A subtle yet powerful managerial adaptation in perspective is to understand that the best way to get your expectations across to Millennials is to start with what they expect of you. We have provided a diagram (Figure 5.2) for you to think about your expectations in relationship to those of Millennials.

Figure 5.2 Expectation Matrix

Learning from Our Success

A great example of flexing came from a golf pro we interviewed. He talked about working with Millennials, “They have so much going on, and I try to work with them so they can do things, but I also try to talk to them about their priorities.” While willing to be flexible about scheduling, he also took the opportunity to communicate his expectations through helping them establish priorities.

A grocery store manager told us that empathizing and being fair was the key to working with Millennials. She talked about trying to understand what they were experiencing and how it affected their job performance. She also gave us new insight that, although there are areas or times in which a manager cannot be flexible, the manager can still build trust by not playing favorites. “They are looking for consistency from me. You don't always have to give them what they want but you do have to be fair.”

Learning from Our Failure

Contrast the good examples with another grocery store manager who insisted that it was the employee who must adapt to his leadership, and, if they did not “get it,” they'd have to go. He justified not hiring twentysomethings in the following way:

They are transitory. They'll occupy the space with no intent of staying…their job just pays the bills. They are focused on what they want but don't see work as a way to get there. I don't want to hassle with the younger ones.

It was no surprise when he told us of his recruiting and retention problems. We can only wonder how many potentially valuable Millennial employees he passed over because of his unwillingness to be flexible. It is not that this person is necessarily a bad manager; rather, it is that he has a generational blind spot that does not permit him to see twentysomethings in terms of their potential to do excellent work and become valuable assets to his organization. Unfortunately for him (and for his employer), the result of his frustration is managerial paralysis. The manager cannot resolve his frustration with the autonomy orientation of the new workforce, and he is not open to the new approaches of working with them that would make his managerial efforts worthwhile. Unfortunately, this particular situation was not unique in our research. In fact, it was quite common.

Best Practice

One retail manager we interviewed developed an excellent solution to the problem of scheduling: He created a scheduling team—made up of regular employees—and empowered them to create and manage the store schedule. He just asked that they take ownership of the schedule and that they get each employee to sign off on it. A headache became a leadership development opportunity, and being a member of this team became a desirable position.

The outcomes were remarkable. All shifts were covered, and employees proactively protected the schedule and held one another accountable because they did not want to lose the autonomy they had gained. Also, the manager was able to build awareness and empathy among employees about the difficulties he faced in some managerial tasks, because the members of the scheduling team experienced the frustration of scheduling firsthand. Finally, the schedule became a symbol of the manager's flexibility. Of even greater significance to the employees, it also became a symbol of their empowerment. Millennials believe empowerment to be a primary role of the leader.

In a Nutshell

There are two major concerns Millennials have when it comes to workplace satisfaction: (1) the freedom to negotiate their job description and (2) management's recognition that they have a life outside of work.

Some might suggest that being flexible with Millennials is an invitation to make managers a doormat for employee manipulation. We disagree. Having no boundaries and being a pushover for employee demands is not what flexing is about. Flexing is not giving in to whatever employees want to do at work—it is about creating an environment in which they want to do work. Flexing is the ongoing conversation between managers and Millennials about, “How can we do our best work together?”

Letting Millennials have it their way makes sense when…

- They desire work-life blending

- They desire a challenge

- They want to find meaning in their work

- They want to have a voice

- They want to gain experience