In earlier chapters, we established that innovation is a key byproduct of collaboration. As we also demonstrated, innovation is not just about technology, business models, or policies but also about social innovation.

Social software is at the core of this innovation, enabling us to create and support new social structures as a way to explore, develop, and adopt new ideas. Establishing a culture of innovation depends on effective communication, strong relationships, and increasing levels of trust. The right social tools can make a tremendous difference to the innovation process and the pace of business transformation.

The challenge for a business leader is to scale the effect of social software beyond individual value, to provide lasting benefit to the organization, and to the broader economy. In a 2008 IBM study that included more than 750 executives from around the world, collaboration was identified as key to fostering innovation and growth.[1] The challenge is making it happen. In Chapter 9, “Social Brain and the Ideation Process,” we discussed the role of social software in the ideation process. In this chapter, we move to the next step, to explore the ways social software can drive innovation and technology adoption, including specific guidance on bringing social innovation to your organization.

Social networking communities are not about the tools but about the people. Tools are just that—tools. That’s why I called this book The Social Factor and not The Social Tools.

The challenge for businesses today is to create an effective, collaborative environment for innovation, leveraging the incredible power of social networking. Great ideas and great innovations come from the minds of people, and socially networked innovation programs are a vital means for empowering people to effectively collaborate in an ever-more-complex world. A successful innovation community ensures that wikis and blogs are not only social venues, but that they also measurably advance the objectives of the company, including the growth of the bottom line.

Above all, the mark of an efficient innovation process is that everything is as easy as possible. Nurture innovators by encouraging them to submit ideas they believe will be of interest to the community. Respond quickly to innovator submissions, using a formal evaluation process that includes an interview and an overview of the innovation program. Be specific about the obligations of the innovator and what the innovator can expect from the innovation community.

Three primary functions are vital to any effective innovation program (see Figure 10.1). In whatever way possible, remove roadblocks to the process of innovation. Employees are too busy with other priorities to struggle with systems—or people!—who stand in the way of their innovation. Second, make wide use of social tools to ensure that innovators can easily reach early adopters and receive feedback on their innovation. Finally, get people excited! A weekly newsletter (or biweekly if you’re short on time) provides a regular reminder about new offerings on your innovation site, along with success stories about innovations that graduated from the program and are now saving time or producing revenue for your company. Consider promoting your innovation program through an organized campaign that includes low-cost giveaways such as ID belt clips and pens with the logo of the program.

Figure 10.1. An innovation program leverages technology and social networking to nurture and encourage innovation.

By leveraging your IT infrastructure and innovation program, you can quickly and efficiently move ideas from abstract concept, to concrete proposal, to prototype, to solution. Innovators should have access to the entire innovation community to test their ideas and receive feedback to improve their solutions. In many ways, an innovation program feeds on itself as ideas are shared across the community.

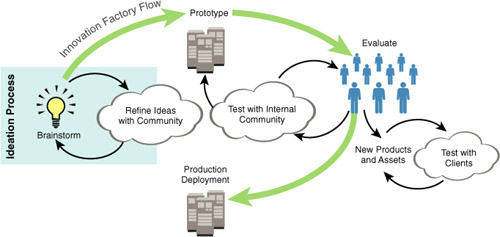

The “innovation factory” concept, shown in Figure 10.2, illustrates the way an idea is transformed by an innovation community into a prototype. The prototype is evaluated by the community, which provides additional feedback to refine the solution. After several iterations, the solution can be deployed externally. Customers and Independent Software Vendors (ISVs) provide feedback to better tune the solution for the intended market. Finally, the solution can be packaged as a software offering or deployed internally to a production environment.

Figure 10.2. This figure illustrates the Innovation Factory Workflow to harvest innovation across your business. This workflow extends from the ideation process to the hardening of an idea into a new product or IT efficiency into the production environment.

The innovation team that supports all this activity should include experts in consulting, project management, technology and infrastructure, marketing, communications, and design. Eliminating the barriers to innovation is the primary focus of an innovation program. Although the combination of an innovation Web site and the team’s vast range of expertise will remove practical barriers for participants in your innovation program, the availability of IT hosting for the program might pose a different set of challenges. To overcome the infrastructure challenges cost-effectively, a dynamic and elastic cloud infrastructure environment should be designed for the innovation program, as we discussed in Chapter 6, “Cloud Computing Paradigm.”

Building on the innovation factory concept, innovations begin with a proposal describing the new concept and the value to the business. The evaluation team then reviews and gathers additional information about the proposal. At this point, the evaluation team might act as advocates or mentors, gathering technical resources to support the innovators, obtaining IT resources, and fostering communities to support the evaluation of the new concept.

The innovation process is composed of several phases:

• Initial value assessment—The first-adopter community collaborates to provide qualitative feedback. Innovation concepts are assessed in this phase for potential value delivered, weighed against a risk assessment based on past experience.

• Early adopter feedback—If the offering passes the first step, it is handed to a literal cast of thousands, representing the business’ internal early-adopter community. This group installs, uses, and tests the limits of the new application, providing feedback through forums and wikis. The innovation team aggregates this feedback and compiles usage statistics, user satisfaction details, and other metrics.

• Value proposition—In this phase, the innovation community uses a value assessment to evaluate the solution, which is then combined with the early adopters’ feedback. A “value number” and a general assessment relating to the offering is the result. This result can lead to the graduation of the offering to become a formal product, a product enhancement, or a part of the internal IT production environment.

• Graduation—Graduation represents the movement of an innovation into the next phase of its lifecycle. When an innovation demonstrates, through metrics and assessments, that it has clear business value, the innovation program provides a conduit to extend the reach of the innovation to the business units. Each innovation might be different in scope and overall strategy, so graduation is also relative to the solution. Some move quickly into production, whereas others might continue for a time in the program until a product plan release is fully developed.

Innovation forums, provided as an integral part of the program infrastructure, yield invaluable insight, user comments, and ideas about each offering. Forums provide a centralized repository in which to gather information relating to software defects, device issues, usability problems, and features not initially considered by the application development team. It is the social interaction between the early adopters who use the code, and the innovators who put forward the solution, that results in a continuous refinement of the application.

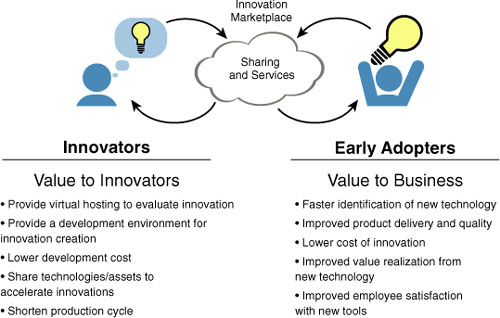

The innovation factory process encourages the harvesting of new ideas, but the value to the business occurs only when innovators effectively interact with early adopters to make use of the innovation. When this synergy occurs, value flows to innovators because they gain the insight of passionate users who understand the business pain points and opportunities. The innovation factory process includes the generation of an idea marketplace where innovators are encouraged to share ideas and assets that can accelerate the innovation process. The production cycle is also significantly shortened because an audience of early adopters always stands ready to test and provide feedback for the innovators.

Businesses benefit from well-defined innovation programs because they can help accelerate the identification of new technologies that can generate new business opportunities. At the same time innovation programs can generate quantifiable return on the investment (ROI) through improvements on delivery time and product quality. Social tools play an important role for innovation programs because employees become more productive and engaged with their ideas when the community expresses interest in the new concept. Figure 10.3 illustrates the value of an innovation marketplace to innovators and early adopters.

Figure 10.3. Innovation programs provide value to innovators and early adopters and can ignite your business with new ideas and products to keep you ahead of competitors.

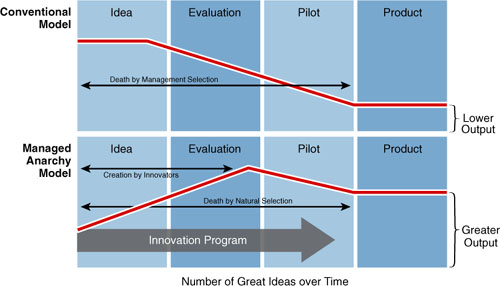

To bypass some of the bureaucracy associated with project plans and the formal waterfall development process, I instituted a “managed anarchy” process (see Figure 10.4). This process allowed multiple competing ideas or implementations of an idea to be developed simultaneously and battle each other. Management did not select solutions, but instead the community was the final arbiter. The “knowledge of crowds” proved to be an effective means to accomplish better innovations in less time, by leveraging community feedback early in the process to correct costly mistakes. This process provided concrete feedback to innovators, and even when their solutions were not selected for graduation, the process provided a helpful educational experience.

Figure 10.4. Advantages of Managed Anarchy over traditional waterfall development process are illustrated here. When teams compete, and are free to express ideas through social tools, more innovation is generated during the evaluation process. The result is a greater number of new products and production efficiencies.

Many companies’ product teams have recently recognized the value of innovation programs as a way to run their internal pilots or supplement their beta programs, and several high-profile software products have been brought through this process to take advantage of the innovation community.

Managed anarchy is also an excellent process for sharing niche applications (also called situational applications[2]), and tools that service the “long tail” of business requirements. This long tail of requirements usually falls outside of regular application development efforts. Teams with needs for specialized tools or information usually remain dissatisfied with formal production solutions created by IT organizations because their needs remain unfulfilled. These kind of situations are typical of software needs represented by the right side of the “long tail,” where software has low volume demand but nevertheless generates great value to its users. This niche application market of “situational applications” focuses on rapid construction of “just good enough” tools to meet a wide array of transient business needs, rather than trying to discover the next great innovation. A great illustration of a situational application is the Genographic Project discussed in Chapter 9. The initial focus of that project was on meeting transient business needs the scientists had for gathering DNA sampling, but the result was an elegant and useful solution for a project that has spanned several years.

We’ve demonstrated the many benefits of social networking in the enterprise, through social ideation and social innovation, and the implicit benefits of social technology to the wider economy, but barriers remain. More than 75 percent of CEOs rated collaboration as “very important” to innovation, and yet only 50 percent believed their firms collaborated sufficiently, and only 8 percent said that they were “very effective” at fostering collaboration across the enterprise.[3]

It seems one of the reasons for these difficulties is a failure to recognize that social software is about more than just tools adoption. A variety of challenges must be faced to ensure successful adoption of social software. For example, organizational silos—the inherent tendency of organizations to partition themselves based on specialization—are one of the biggest inhibitors of collaboration. Part of the process for overcoming silos is to encourage a shift in the mind-set from “knowledge is power” to the mind-set that “shared knowledge is more power.”

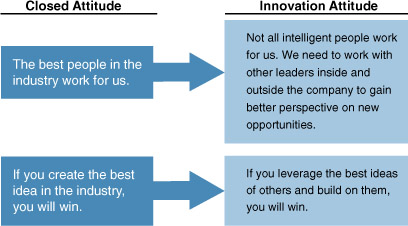

Honestly facing the reality that your business doesn’t have a monopoly on good ideas, nor that it has all the smartest people in the industry, will go a long way to encourage participation in broader collaboration. Adoption of social software tends to change attitudes and break silos. Also, as collaboration increases within a company, ideas are generated more frequently and business transformation is accelerated by new innovations (see Figure 10.7).

Figure 10.7. Social tools create a cultural change in the organization, moving from a “Closed Attitude” to an “Innovation Attitude” that encourages innovation and collaboration.

Another barrier to effective social networking can be the misperception that participants will engage in bad behavior in a social networking environment. Anonymous or pseudonymous rogue posters on external social networks might make people wary of similar behavior in the business setting. To encourage the trust needed in the business social networking environment, you should require the use of real names. Real names also help establish the credibility of a contributor who offers information, and the experience with more than 350,000 IBMers demonstrate that in the business environment, social software is more effective when anonymity is not permitted.

People are often also concerned that social software will add more work to their already-full plates. Success stories go a long way to convince others that time invested in social software can produce excellent returns. For example, Sacha Chua, a strong advocate for social software at IBM, talked about the increased efficiency she enjoys through her use of social software.

“Taking a few extra minutes to share a tip, solution, or presentation,” Chua said, “saves me so much time. I calculate that I’ve spent about 100 hours preparing presentations to reach about 2,000 people. Spending a few extra hours to post all those presentations online, I’ve reached about 10,000 people. That’s a small effort for five times the reach.”[4]

Although behavioral change is a key (if not primary) inhibitor to adoption of social networking, poor tools and skills can also get in the way. Poor implementation, lack of integration into the workflow, poor usability, accessibility problems, platform issues, and stability issues can dishearten all but the most intrepid adopters.

Finally, readiness levels within an organization will also affect the rate of social software adoption. To determine your readiness for social software, the answers to questions similar to the following can provide valuable insights and prompt useful planning discussions:

• Is your organization risk averse to new approaches or technologies?

• Do departments work in silos?

• Are there established online communities or social networks within the organization?

• How committed to or interested in social software is the organization?

• Is there executive sponsorship or buy-in?

• Are business goals clearly defined?

• Are there policies for online information and user identification?

• Will current business processes be disrupted or made redundant with new forms of interaction? What does the transition look like?

• Does the company have the appropriate software capabilities?

• Will the company IT infrastructure support social software?

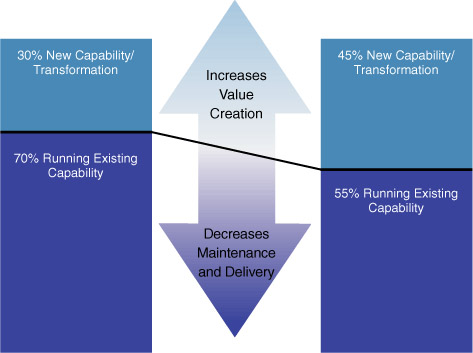

A company that doesn’t invest in the future doesn’t have a future. This is why innovation programs and social tools are so important to the growth of a business. The more efficient a company is, the more money it shifts from the process of “running” the enterprise to “transforming” the enterprise.

On average, CIOs spend 70 percent of their budget keeping the current system up and running—this is a combination of fixed and variable costs that includes IT infrastructure and support. By contrast, only 30 percent is invested in transformation and innovation projects. In many ways, the amount of investment allocated for transformation is a good barometer of future success. A balance that allocates closer to 45 percent for innovation and 55 percent for infrastructure operation seems to be a more successful mix (see Figure 10.8). Market forces today require constant differentiation of products and services, so an effective innovation and transformation program is crucial for keeping your business in front.

The incredible power of social networking in the enterprise has been dramatically demonstrated at IBM. We hope these lessons are helpful if your organization is in need of a business case. If you are in the processes of creating a business case for social networking tools, it is vital to articulate the value of social software to gain support for its implementation. This can be done in several ways:

• Usage metrics to capture social software adoption trends

• Success stories to provide anecdotal evidence of value

• User survey data to demonstrate improved productivity and usefulness

• Social network analysis to demonstrate the impact of improved relationships on problem solving and organizational efficiency

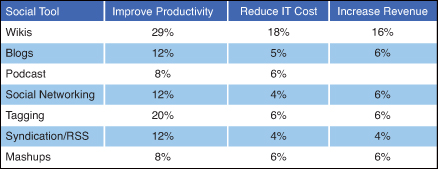

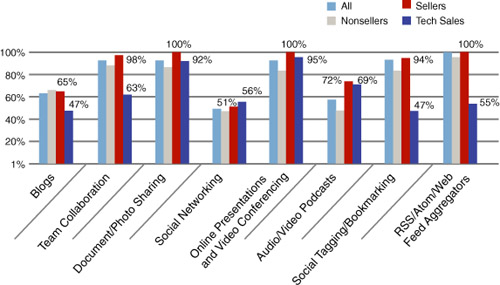

Perhaps not surprisingly, IBM found that the use of social software improved the sales organization’s communication, leading to enhanced team performance. Specifically, these tools helped identify areas in the sales process that needed some improvement. For example, shared community spaces allowed teams to identify customer needs faster and tap into the team’s knowledge of previous client interactions. Previously, this kind of knowledge was locked in the memory of a few salespeople, but the usage of social software freed up valuable institutional knowledge. Tools such as wikis, jams, blogs, mashups, and virtual meetings helped the IBM sales force create sales collateral material like demos. They also identified prospective opportunities faster and created effective sales strategies more quickly. Social tools are especially helpful to sellers and technical support personnel because of the large number of people with whom they interact. A survey of the IBM sales community included more than 20,000 participants and revealed interesting patterns about the perceived value of social activities, depending on job role (see Figure 10.9).

Figure 10.9. Survey results of IBM sales workforce on the impact of various social tools, categorized by job function. In November 2008, participants were asked to rank and quantify productivity increases due to social tools. This is a great example and proof point of the tremendous positive influence social software can have on the productivity of a workforce.

Interviews with literally scores of CIOs and CEOs, along with extensive surveys within the IBM IT community, allowed my team at IBM to quantify the significant business advantages available through social tools. These advantages were categorized in three distinct areas—productivity improvements, IT cost reductions, and revenue increases. Improvements to the businesses were consistently realized within 6 to 18 months of deployment (see Figure 10.10).

With a solid understanding of both the methodology and ROI, there are some central principles that can help ensure the success of your technology adoption and innovation program:

• Social networking—Not surprisingly, social networks are key to technology adoption and innovation within your organization. Recruiting early adopters will help encourage others in the use of social tools. As these social software pioneers make their presence and expertise known and explore ways to promote their reputation as trusted sources, others will follow. Tools such as expertise location, profiling, and reputation tools can also help seekers and contributors quickly connect, accelerating the innovation process. Goals identified at the beginning of the innovation program should be tracked using performance and achievement metrics (for example, number of participants, number of wiki contributors, and so on).

• Transparency—The free flow of information across the enterprise and the creation of a level playing field for all employees and customers are central to the concept of transparency. Transparency can transform companies into true “meritocracies,” where recognition and advancement is based primarily on productivity and maximizing value to customers and stakeholders. This transformation naturally creates a more productive environment. Customers benefit from transparency by getting better products, less costly solutions, and better integration. Perhaps most importantly, customers experience increased responsiveness to product suggestions and requests. Increased transparency benefits employees, raising their visibility to management and their social community. This philosophical change gives employees the freedom to act on new ideas and increases collaboration across the organization. Provide the tools needed for employees to freely share their ideas, but also have the process that supports and encourages innovators to create and act on their ideas. By providing tools to encourage transparency, management nurtures a culture that is supportive of innovation.

• Support structure—Social tools, IT infrastructure, and budget are the three pillars of a successful innovation program. Ensure the selected social tools fit into the existing workflow and integrate with other IT systems. Social tools support the creation of social networking communities, which are crucial for generating new ideas relevant to the business. With the appropriate and properly budgeted IT infrastructure, innovative ideas can more easily flow from socially networked teams. Without a nurturing support structure, employees with good ideas might become discouraged following on with their ideas or simply won’t get started because the inertia is too strong. To encourage innovation, lower barriers wherever possible.

As we’ve said, innovation programs should have their own budget and IT infrastructure, separate from the production environment. Many CIOs have asked me, “How can I replace current processes with streamlined methods that leverage new technology?” In many ways, this is like asking how to change tires on a moving car. The reality is that it is difficult to change a process within the same infrastructure where a legacy application runs. The first time the new process fails (and it will fail because it is new and not as robust as the legacy system), the innovation project will be killed. For this reason alone, a separate innovation environment is crucial.

Similarly, securing an “innovation budget” and an “innovation IT infrastructure” effectively isolates the relatively fragile process of innovation from the market forces of the business. Think of the innovation budget as a small venture capital investment. You’re using this budget to fund the best ideas for a defined period to demonstrate to the company the value of focused innovation. The budget can fund resources, pay for services, and mitigate risk. The innovation IT infrastructure deploys innovations separate from the production environment to avoid conflicts and potential instabilities. Cloud computing can be a great setting for innovation programs. IBM, Amazon.com, Microsoft, Google, and many others provide cloud computing options that minimize capital expenditures and support the structure for innovation programs.

Mature technologies have an advantage when it comes to procuring a budget—an identifiable ROI. Innovation programs, by definition, lack the hard numbers that can justify a specific budget. As we said, viewing the innovation program budget as venture capital makes it easier to get started. Some disruptive technologies can take two years or more to mature before being seriously considered as a replacement for legacy technologies. A separate investment for innovation provides the cushion for innovation programs to prove themselves, rather than being terminated prematurely.

Innovation is hard work. Time and money need to be focused on the effort if transformational change is going to happen. An innovation budget helps pay for key resources to devote 100 percent of their time to the innovation to ensure the success of the project. For an innovation program to be successful, teams don’t need to be collocated. Instead, good social networking tools enable collaboration and a strong sense of community across the team, without regard to geography.

The challenges of today’s economy and the global nature of business require us to think in fundamentally different ways about success. With appropriate attention to innovation, particularly in the context of social networking, we can ensure that our businesses remain profitable and consistently ahead of the competition.

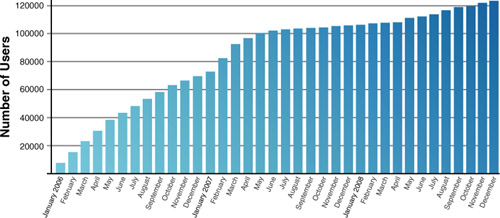

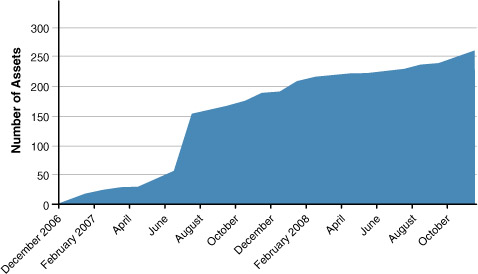

• The Technology Adoption Program at IBM had a fast adoption rate of less than three years. More than 125,000 IBMers joined the innovation program and transformed IBM business processes and business.

• Innovations are best generated within an innovation factory workflow to harvest innovation across your business, from the ideation process, prototyping, and evaluation to deployment.

• Free your organizations to think out of the box and achieve the impossible by embracing an innovation process that is based on the Managed Anarchy model instead of traditional waterfall methodologies.

• Encourage participation in broader collaboration by acknowledging that your business has neither a monopoly on good ideas, nor all the smartest people in the industry. Adoption of social software changes attitudes and helps break silos.

• Use social tools to foster social networks within the business to transform your corporate culture into one that embraces innovation. Embracing change and innovation can energize your employees and accelerate business growth.

• The amount of investment allocated for transformation is a good barometer of the future success of a business. For meaningful transformation in the Social Age, a reasonable balance is to allocate 45 percent of the IT budget to innovation and new capabilities and 55 percent committed to running the existing infrastructure.

• Innovation programs measure ROI through cost reduction metrics and reduced time-to-market for new products. The IBM TAP program provided an estimated ROI of above 50 percent.

• Key success factors for innovation programs include appropriate implementation of social networking tools, business transparency, and a support structure.