The compounded technological advances of the past 200 years have reduced the cost of communication to a point that many take it for granted. Low-cost communication has created dramatically increased efficiency, which has become a catalyst for entirely new social and business organizations. More complex social structures and intricate business collaboration networks are now possible and generate incredible organizational efficiencies in businesses of all sizes.

Traditional hierarchical structures have great value to organizations where information is controlled or consolidated at the top. Military services depend on a rigid and well-defined hierarchical structure, but dynamic market forces have forced businesses to rethink this traditional, top-down approach. Business strategists realize that hierarchical structures just don’t work as effectively in the Social Age. In an earlier stage of development, businesses focused on economies of scale, growing as fast as possible, and relying on highly centralized company structures. Strategists and executives had the information required to lead the organization, and they pushed the information down to the work-force through organizational layers.

In the Social Age, information resides in the network, within organizational layers. This creates a new world order of communication, requiring different ways of working and thinking. Add market pressures, and increasing globalization, and any business that hopes to survive must respond aggressively. As businesses “globalized,” organizational evolution quickly moved from highly centralized hierarchies to multinational structures with independent businesses empowered to optimize for local markets.

But the multinational structure has proven to have some drawbacks. The primary deficiency of this model has been the duplication of services driven by local business units optimizing for their markets, but failing to take into consideration the overall corporate financial perspective. For example, businesses structured around the multinational model tend to create duplication of IT solution procurement and fulfillment as they satisfy specific requests from each regional team. This can create a plethora of solutions that drive IT costs higher and introduce operational inefficiencies. These same needs can be addressed more cost-effectively with a well-defined supply chain IT solution to optimize the business. A more effective way to handle this problem is through the establishment of a shared service that can be customized but not duplicated by the regions.

The Globally Integrated Enterprise addresses the deficiency of the multinational model. The Globally Integrated Enterprise is a more efficient organizational model in which common business processes are standardized to lower the cost of IT and simplify overall end-to-end delivery. Increasingly, companies are moving toward the Globally Integrated Enterprise model—radically challenging their existing business model, embracing disruptive technologies such as cloud computing, and most importantly, providing the tools and encouragement for employees to work in communities. In the Social Age, companies will continue to transform their organizational structures to become more agile and community-centric. They will have loosely connected structures arranged around business communities that are fluidly formed and disbanded based on new projects, innovation efforts, and market demands. Employees will come together for a project, based on their relevant expertise, and then disband when the project concludes.

New collaboration and social networking tools also help create better global perspectives. Teams collaborate across country boundaries, language differences, and cultural barriers to ensure everyone has an equal voice in the process. These tools create a flatter, smarter, and more nimble business structure—a business structure that truly leverages the benefits of a global marketplace by integrating the power and energy of a worldwide “business crowd.”[1] These expanded business communities offer a clear competitive advantage to organizations that embrace them. Social networking tools enable the entrepreneurial team of a company to more easily come together around difficult challenges and efficiently create innovative solutions.

Communities supported by social networking tools typically encompass a variety of skills, cultures, and locations, but common goals and passions motivate them and bind them together. The low cost of participation—in both effort and expense—often leads to these communities being noncollocated. By expanding the community geographically, those who participate are often among the recognized experts in their fields. Ease of participation and higher levels of expert participation create more valuable outcomes, and participants tend to work together better and share information more readily than traditional collocated groups.

Just as happens in society at large, these ad hoc communities also develop their own sense of identity and culture that might only be loosely associated with the corporate “vibe.” Although everyone might not wear a company-logoed shirt, these communities are typically marked by a drive to excel and to contribute to the business in a meaningful way. Participants are respected for the value they provide to the community, rather than for their hierarchical corporate position or social status. In many ways these communities create their own work ethic that encourages members to contribute and generate value through healthy peer pressure.

Objections might be raised by those who are new to this model. “How can someone halfway around the world relate to and work with someone here in the states? After all, aren’t the nonverbal cues we receive from our colleagues, along with our powers of observation about their workspace, important in our working relationship?” Both of these are excellent questions and both get at the heart of what makes socially networked communities so powerful.

In today’s global marketplace, teaming with people you’ve never met face-to-face is increasingly common. These colleagues might be from completely different cultures, have completely different business practices, and even be working while you’re sound asleep, ten time zones away. But to get the job done, you have to effectively collaborate with these distant colleagues, just as you do with the team in the offices and cubicles all around you.

In a face-to-face work environment, verbal and nonverbal cues help you work with colleagues. Through casual conversations, or by observing coworkers interact with each other, you gain valuable insight into personality and work style. Even the way people decorate their offices can help you connect with them. Knowing the whole person can be vital for team success. We all tend to gravitate toward people we like, and knowing someone socially can build a better working environment. The challenge is to foster this same interpersonal connection and team spirit among people who sometimes work in locations separated by 10,000 miles or more.

Social networking, in this case, becomes something of a virtual representation of your workplace. What do people in your office know about you just by observing your work space? Malcolm Gladwell says that the best way to find out about a job candidate is not by any of the usual methods. “Forget the endless ‘getting to know’ lunches. If you want to get a good idea of whether I would make a good employee, drop by my house one day and take a look around.”[2]

With social networking we can hang our family pictures on the virtual walls of our blog. We can share the latest news about our local sports team, or highlight a competitive sales win. Did you just finish your first marathon? Perhaps you’ll find that five people in the Mumbai office are marathon runners as well. In addition to chatting around the water cooler about a recent customer experience, many employees are now blogging about it as well.

Share bookmarks with your teammates by using a social bookmarking site where your collective knowledge is always available. Show your preference for a sports team by joining a fan club on a social networking site. You can also share your membership in professional organizations. With social networking tools there are countless ways to let your colleagues know you better, which ultimately improves teamwork and camaraderie.

Socially networked business communities work together continuously, leverage external channels, and remain loosely connected to other teams and business units. This structure is successful because of constant information sharing and the transparency created by technologies such as wikis, blogs, and other services that socialize the enterprise in a way that information becomes equally accessible to everyone in the business.

The openness and transparency of collaborative communities—both outside and inside the confines of corporate firewalls—represent a significant shift that overturns traditional delivery and management approaches.

The loose structure of these communities provides profound benefits to the organization. Rather than being constrained by traditional department boundaries and hierarchies, Social Age organizations can quickly redeploy resources or restructure within the social networking model as opportunities or challenges arise. For the Globally Integrated Enterprise, such nimbleness is a powerful competitive advantage.

Unlike monolithic corporations of an earlier age, the Social Age organization is not threatened by change but is hungry for it. The Social Age organization is interested in innovation as a way to continually generate value for customers and society. It is truly integrated globally and driven by the energy of its communities. It is disruptive by nature, always questioning the status quo and responding quickly to opportunities. Perhaps above all, the global corporation of the Social Age is genuine with its employees, not just generous. This is significant because Social Age employees often seem to value transparency, honesty, and camaraderie in the workplace more highly than they do additional compensation. The unprecedented wealth experienced by the Net generation has created profound social needs and expectations of higher ethical behavior in the work place.

As we explore later, there is an abundance of retail social tools available on the Internet from which your business can choose. These tools enable anyone to create a Web site to exchange ideas, brainstorm, or collaborate with others. These services are typically free if you’re willing to give up some privacy, receive advertising, or tolerate occasional service outages. Similar tools have been adopted internally at many corporations, but with key adaptations to provide more reliability, privacy, and business efficiencies. Advertising has similarly been stripped out of these tools, which is seen as an unnecessary distraction in most corporate settings.

Along with easy-to-access and user-friendly tools, the Social Age will be marked by communication that continually becomes more effective and affordable. Any business can use—and take for granted—wikis, blogs, micro blogs, instant messages, collaboration tools, tag services, smart phones, cloud data storage, 3D virtual office spaces, customized business search engines, standardized transaction services, and many other services that enable formation of business communities.

CEOs and CIOs are increasingly acknowledging and validating social models of interaction and communication. We have seen investments of up to 20 percent of IT budgets in collaboration and innovation initiatives with customers and employees. European conglomerate Rheinmetall is a good example of a company with a substantial commitment to social networking and collaboration tools.

With multibillion Euro annual revenues, Germany’s Rheinmetall is a leading automotive and defense technology company with locations in Europe, North and South America, and Asia. Rheinmetall has offices in 17 countries and 60 locations, and uses a variety of social tools to support its worldwide workforce of 19,000 employees.

CIO Markus Bentele talked about the challenges of implementing social software at Rheinmetall. “We have a legal structure for the organization we must maintain,” Bentele said, “but we wanted to build a virtual structure spanning these different entities, and [social tools] are enabling us to do this.” The automotive business of Rheinmetall has five product divisions with a total of nearly 12,000 employees. “We wanted them to be able to network and tap into the entire organization for expertise, help, and ideas,”[3] said Bentele. Rheinmetall needed to connect people from various parts of the organization into virtual teams and communities to effectively drive the business.

“Along with subsidiaries in Europe, North America, and Asia,” Bentele said, “we maintain a tightly woven network of branches and company representatives. Proximity to the customer is one of our most important principles. Rheinmetall needed a single point of entry for all employees worldwide that would give them access to the collaboration tools and all their intranet and business intelligence systems.”

Social networking was strategic to Rheinmetall for growing its business. “We experimented with a few social tools like wikis and blogs,” Bentele said, “to see how they could be used in business environments, and users asked for more. We also identified that we needed to implement a social computing system for several important reasons.”

Bentele went on to list three primary drivers of social networking at Rheinmetall:

• A tool in the recruiting war for talented employees—Social networking provided Rheinmetall with credibility as a Social Age company in the eyes of job candidates.

• A paradigm shift in communications—New employees and trainees communicate in different ways—they don’t use e-mail, or write things down; they are expert at communicating via instant messaging and social tools such as blogs. Without social networking, communication at Rheinmetall would suffer and collective knowledge would be limited.

• Evolutionary changes in information location—No longer do Rheinmetall employees “go it alone” when it comes to research. Millennials, including those at Rheinmetall, grew up with Wikipedia. They get information from established networks and rely on those networks to get things done.

It is fascinating to hear Bentele explain the role of demographics in the use of social tools at Rheinmetall: “We have four generations working at our company,” Bentele said. “The first are the older executives who still like to work with paper. The second generation work mostly with e-mail and groupware; the third use instant messaging, and the fourth—the newest recruits—work in wikis and blogs.”

Bentele said that these different approaches aren’t so much a function of age as they are a function of cultural influence and mind-set. As a result, Rheinmetall offers flexibility in the use of social and communication tools, which Bentele believes fosters a more productive environment. “It is [simply] not possible to mandate that everybody use the same tools,” says Bentele.

For other CIOs considering social tools, Bentele offers an enthusiastic endorsement: “This technology is not just an opportunity; it is a necessity.”

Social networking was embraced by the general public before it was embraced by most businesses, and its influence continues to grow in all areas. The Social Age generation is being conditioned—as no previous generation has been—to feel comfortable sharing information, collaborating with distant colleagues and acquaintances, having a global mind-set, and valuing (not just tolerating) transparency.

Our expectations during the Social Age have risen as well. In the dot-com era we were pleased with a web page that was fairly current that could execute a commercial transaction. The Internet was originally thought of as only a static content delivery model. As such it was just a better, faster print medium; it was primarily unidirectional—content producers to readers. There was little if any bidirectional capability in the early days. If someone had valuable information to share with others, there was no easy way to get the word out. Although everyone could set up their own Web sites, this just exacerbated the problem—now there were just that many more isolated islands of information.

During the dot-com era, a plethora of Web sites were created with no collaboration interfaces between them. New web crawlers and search engines tried to bridge the gap between these isolated data sources but didn’t provide the interactive experience that most people instinctively desire as a natural social behavior. After all, we are social animals!

The transformation to dynamic bidirectional interaction—a social-centric Internet—was driven by Web 2.0 technologies, higher bandwidth capacity, and easily accessible new media. Users today expect web applications to be interactive—capable of receiving input from readers and benefiting from the input of others using the application. Customers now demand a way to rate products and have an easy way to complain about or praise a product. The pressure is building for all businesses to provide a channel for customer feedback and social collaboration.

For your business, however, the Social Age means much more than just creating an electronic suggestion box or customer feedback form. True social networking transformation creates self-sufficient communities that can actually help run part of your business. For example, a business can foster a socially networked customer community to work jointly with its own support team to provide better customer service. These business communities can help fix bugs, build an effective communication campaign, select the next product enhancement, or even share ideas for new business directions. No business has a monopoly on good ideas. Why not tap into what might be your best source of new ideas for your product—those who already use it!

More powerful social networking solutions are now being created for businesses through Services Oriented Architecture (SOA)[4] and web services, which standardize social networking tools and allow them to be connected with other business services. The current barrier between retail social networking applications and enterprise social networking tools behind the firewall will continue to diminish as these open interfaces are embraced. This standardization of web services has enabled corporations to exploit external services through a set of modular encapsulations of services or composite applications that can be used with enterprise web applications.

New social networking services, based on web services, will accelerate business transformation and fundamentally restructure the enterprise around communities. Loosely coupled social connections—those connections that you create through social networking, with people you barely know, but with whom you associate by profession, interest, or project—will play an important role in this transformation. These communities, empowered by SOA and web services, will realize the full value of social connections to collaborate with knowledgeable external and internal participants, and facilitate globalization of the enterprise.

Social networking tools in the business world are about transformation. They are about supporting a new world order that democratizes and socializes business processes. They create more productive and efficient environments for communities to collaborate on projects—with local flavor and worldwide scope.

Organizations of all sizes are exploiting Social Age tools to encourage more effective collaboration by their employees, clients, and business partners. Employment agencies make extensive use of professional networking sites such as LinkedIn.com to identify potential candidates. Likewise, employers use LinkedIn.com to advertise jobs. Retail companies use social networking tools to drive sales and marketing. Everyone, it seems, from giant corporations to grade-school students, are selecting products and suppliers with reference to satisfaction ratings and reviews. But for most organizations, the greatest value in social networking is found in these six areas:

• Teaming and collaboration

• Succession planning

• Recruitment and on-boarding

• Content and expertise capture

• Skills development

• Innovation

Teaming and collaboration are the primary drivers of social networking at most organizations. These tools provide valuable support to employees, business partners, and clients. The agility and reach of the organization is improved when tools are available that help people get to know each other better, ultimately leading to more effective team building and productivity. Particularly in the area of research and development, effective collaboration around key initiatives is vital to the future of your organization. In a 2008 paper, the journal of the International Association for Human Resources said that people with better social capital:

• Close deals faster

• Enhance the performance of their teams

• Help their teams reach their goals more rapidly

• Help their teams generate more creative solutions[5]

Recruitment and on-boarding of new employees is improved with access to social tools. Services external to the firewall (such as LinkedIn.com) can be used to advertise for and find potential hires. A new hire can then access internal social tools to quickly become productive. For example, wikis offer extensive how-tos. Profiles and blogs provide access to mentors, along with the capability to “follow” someone by subscribing to a feed of their activity, as we discuss in Chapter 7, “Social Media and Culture.” In addition, the new hire can find corporate information and navigation assistance in wikis and FAQs. In 2008, the International Association for Human Resources also noted, “Social capital is a key driver in employee retention.”[6] Social tools are useful in recruiting talented employees, but the sense of camaraderie these tools build within the organization is vital for retaining talent.

Skills development is accelerated by being socially networked to existing communities of expertise or interest, and exploring e-learning content adds depth to those skills. Weaving social tools into e-learning has reinvigorated this technology over the past five years, making it more relevant. Everybody can contribute content to e-learning, and social tools allow tagging, ratings, and recommendations. Also, while consuming e-learning, users can now have access to other learners, experts, and communities—in context—through social networking.

Succession planning is more easily accomplished when expertise profiles and skills assessments are current and complete. Social networking tools provide the information vital to succession planning at all levels of the organization. For western companies, which are planning for large numbers of retirees in the next decade, this issue is particularly important.

Content and expertise capture, or the accumulation of tacit knowledge, is significantly enhanced with social tools. The longer someone participates in a social networking community, the more they contribute. This low barrier to entry leads naturally to the next stages of social networking involvement—contributing media, new or updated content on wikis, and developing personal profiles. Media contributions can include anything from spreadsheets and documents to more social forms such as video and podcasts with presentations or screenshot content. Users might ultimately publish blogs or create and lead new communities.

Finally, innovation is arguably the area where social networking is having its most powerful impact in business. In Chapter 10, “Social Innovation,” we explore this topic in detail, using an extensive real-world example at IBM where more than 125,000 contributors collaborated on literally hundreds of exciting new technologies.

For a more empirical understanding of the effectiveness of social networking in the business environment, my team created a project in which IBMers could join a study about the degrees of separation between IBMers and their patterns of communication.

The study was performed under a rigorous scientific process and strict privacy rules were enforced on communications related to e-mail, instant messages, blogs, and wikis. This strictly volunteer project was by invitation only, and anyone who wanted to participate had the opportunity to sign in. Anonymity was ensured through replacement of personal information with numbers. Company confidential and personal sensitive data were also removed.

One of the studies included approximately 30,000 employees using e-mail and instant message, whereas the second study included approximately 157,000 employees using wikis. These studies provided powerful examples of the ways socially networked business communities exchange information and work together.

The study revealed that communities had a few participants who performed the majority of the communication that held the team together. Also, more frequently than expected, the true community leader was neither the formal leader nor the primary keeper of the information (institutional memory).

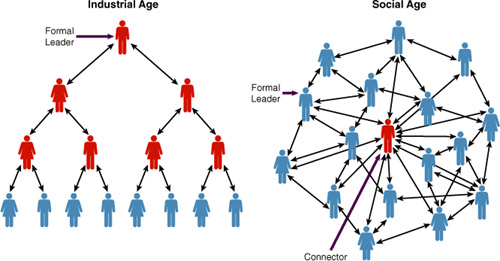

Instead, as illustrated in Figure 2.1, the communities behaved as organic entities that organized around people whom Malcolm Gladwell described as connectors.[8] These connectors kept the team moving and were instrumental in conflict resolution. In essence, these communities formed an effective informal organization. All these organic entities were free to collaborate and solve problems as the situation and business changed. Natural leaders emerged depending on the expertise required and the problem confronted. This community behavior is characteristic of the Social Age, when the organization is given freedom to interact organically and is coupled only loosely with a formal business structure.

Figure 2.1. The true community leader in the center of the Social Age organization (right diagram) is not the formal leader, but is providing most of the communication and is linking the team members together. The formal leader is often a peripheral contributor rather than at the top of the organization as in the Industrial Age.

The old adage “knowledge is power” remains true, but in the Social Age there’s a shift underway. Individuals previously held information as a way to hold onto power. Now information is everywhere, and those who are most adept at sharing that information are the ones who suddenly have the power.

With all social networking, the value of information increases with the number of people contributing to or distributing it. This is one of the tenets of all Web 2.0 systems, as exemplified perhaps most dramatically by Wikipedia. Another factor encouraging the sharing of information is the incredible speed with which some information becomes “old news.” There’s a drive to gain recognition for sharing the information but also for being “first.” A healthy competition to share information quickly is unique to social networking.

Likewise, employees make valuable connections using social tools, both inside and outside the organization. Mark Granovetter, in a 1973 paper, talked about Weak and Strong ties in traditional (nonelectronic) social networks. (A theme also explored by Malcolm Gladwell in The Tipping Point.[9])

Granovetter suggested—perhaps counterintuitively—that weak ties are more valuable. In other words, when people are less strongly connected, there is often more value in a relationship.[10]

The example often cited to support Granovetter’s thesis is a job search. You are more likely to find useful job leads through weaker ties in your network (a friend of a friend) than you are from your strong ties, such as immediate family and work colleagues.

Granovetter took up the topic of social ties again in 1983, when he acknowledged the importance also of strong ties. “Weak ties provide people with access to information and resources beyond those available in their own social circle,” he said, “but strong ties have greater motivation to be of assistance and are typically more easily available.”[11]

Social networking in an organization can help to form and cultivate new weak ties while strengthening and maintaining strong ties.

The following chapters reveal the way employees can leverage the power of social tools to improve internal enterprise processes, create new business opportunities, satisfy internal social needs, and enhance their world. We also explore more closely the social instincts that are behind the strong human tendency to collaborate around communities.

• The Social Age is leading to the rapid reappraisal of traditional “top-down” management hierarchies and tapping into the information that resides within the organizational layers. Loosely structured and highly efficient communities, focused on specific tasks, are replacing less efficient traditional organizational models.

• The successful Globally Integrated Enterprise uses social networking to radically challenge its business model, embrace disruptive technologies, and facilitate and encourage employee communities.

• Social networking tools are widely available, and the increasing uses of SOA technologies allow enterprises to leverage external services and interact with a variety of social networking tools.

• Company blogs are a great way to record institutional memory and provide a channel for expression to the most innovative employees.