Historic eras by definition can be fully understood only with the passage of time. Perhaps you witnessed the World Trade Center attack on September 11, 2001. It was a singular event, but we now recognize that it foreshadowed the long, expensive, and painful “war on terror” in Iraq and elsewhere, and it led to a soul-searching re-evaluation of U.S. foreign policy. Perhaps in August 1981 you heard that IBM® had introduced the personal computer, which made computing available to everyone for the first time—a singular event, but one that marked the beginning of one of the most remarkable eras in the history of humankind.

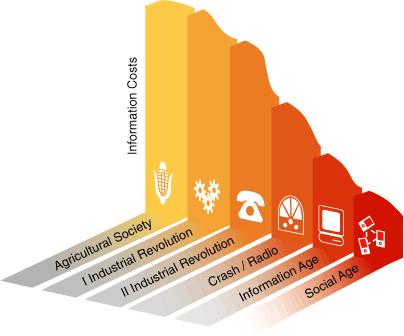

To better understand how we arrived at the Social Age, a brief overview of the shape and impact of earlier eras is vital. Perhaps most notably, these eras were marked by an ever-decreasing cost of both communication and transportation. Together these decreasing costs were fundamental to the eventual dawn of the Social Age.

We need to return only to the mid-nineteenth century to see the first seeds of the Social Age being sown. At an early stage of the Industrial Revolution, there was a massive transformation of the labor force. A shifting skill set naturally followed the financial rewards, which were no longer found in farming, but in manufacturing. Because manufacturing was concentrated in large population centers with deep labor pools, the bucolic, community-oriented farming lifestyle vanished for many. In its place were congested cities and noisy, overcrowded, and dangerous factories. Apart from conversations with neighbors or coworkers or the occasional letter, communication for these people was rare and expensive. Long work hours, low wages, poor working conditions, and poor transportation all made extensive communication an unaffordable luxury.

The events that followed transformed America forever and represented the first quantum leap toward the Social Age. The steam engine, an ever-growing rail system, and perhaps most profoundly, the advent of inexpensive long-distance communication by telegraph, all served to dramatically catapult both social and economic growth.

In 1849, Samuel F. B. Morse simplified bulky and unwieldy telegraph designs into a practical and easily deployable device.[1] Not content with merely increasing communication efficiency, Morse quickly leveraged his telegraph technology into a revolutionary system that automatically signaled the location of trains, dramatically increasing safety on the growing rail system. Telegraph lines deployed at the same time as new railroad track ensured that telegraph would become the de facto communication standard of the early Industrial Age.

Coupled with Morse code, these extended telegraph lines served to provide a quick and low-cost communications channel. Although there was nothing intuitive about Morse code (short and long signals could be sent and deciphered only by highly trained telegraphers), it was nevertheless by far the fastest communication method of its time. As we explore in detail later in this chapter, the railroad safety features offered by telegraph and the broad deployment of the vastly improved telegraph technology are excellent examples of the way standardization plays a key role in lowering barriers to adoption.

Communication expanded still further with President Lincoln’s signing of the Pacific Railway Act, which was created as part of Lincoln’s ongoing vision of national unity. Subtitled “An aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri river to the Pacific Ocean, and to secure to the government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes,”[2] the act was signed in 1862, and the project was completed in 1869, four years after Lincoln’s death.

For the first time, the East and West coasts were knitted together by rail and telegraph lines. Some of the first telegraph lines in the project were used by Lincoln to receive Civil War battle reports, and the general public used them to communicate across the country with loved ones. For the first time, people could stay connected quickly and at relatively low cost with people who moved West during one of America’s greatest periods of migration.

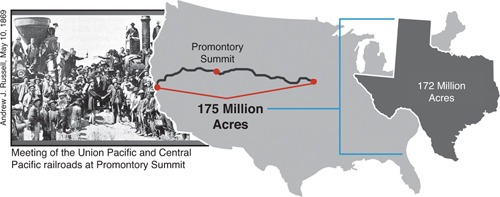

The monumental scope of the Pacific Railway Act is difficult to fully appreciate today. To ensure the success of the project, the government provided more than 175 million acres of land to build it on, 3 million acres more than the size of the state of Texas[3] (Figure 1.1). Although government assistance was important, further efficiencies in the Pacific Railway construction were possible through standardization of railroad track and significant advances in the development of steel. The railroad was one of the largest and most important government projects of the Industrial Revolution, and it stands as an engineering marvel of its time.

Figure 1.1. The 175 million acres donated by the U.S. government to build the Pacific Railroad is greater than than the size of Texas. A celebration on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah, marked the completion of the heroic effort to join America from coast to coast by rail for the first time.

The competitive advantages gained by the completion of the railroad are immeasurable and quickly propelled the United States to a position of global economic power, which it retained for many years. Telegraph cables were soon ubiquitous across the United States, and in due course were laid across the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, creating a connected world—via Morse code—for the first time. The Associated Press was a creature of the telegraph, formed by newspaper publishers who recognized the tremendous profit potential of instantaneous worldwide news bulletins.

The Pacific Railway Act transformed an expensive and often life-threatening westward journey of more than three months to just over one week of relative comfort and low cost. The act not only lowered transportation costs but also enabled vastly improved communication across the nation.

This lower cost of transportation and communication, enabled by the railroad and telegraph lines, transformed the nation and supported the collaboration required by the rapidly expanding country.

The next phase of the Industrial Revolution, which some historians call the “Second Industrial Revolution,” occurred from 1875 to the 1920s, and represents another leap in economic and social development. Electricity, petroleum, automobiles, telephones, and new steel industrial applications generated a host of innovations. Together these advances enabled increased economies of scale through lower cost of communication and manufacturing; and more importantly, for the first time they provided workers with affordable transportation that made longer-distance commuting possible.

The combination of the automobile, electricity, and telephone created the momentum that generated explosive urban development. The automobile increased the distance and speed that food and other goods could be transported. Electricity powered a host of innovations, including electric-powered refrigeration, which also increased the distance goods could travel and their shelf life after they were delivered to a customer. Finally, the telephone was instrumental in maintaining connections over long distance in the new urban and dispersed society. These inventions changed society by empowering and freeing individuals to communicate better and travel farther and faster, at a lower cost.

Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, invented in 1876, leveraged the established telegraph infrastructure to vault communications to the next level. The telephone established a new, low cost communication, which consequently supported further dispersal of communities into the suburbs and encouraged better long distance communication.

Now a community included not just those we talked with face to face; now it included anyone we could talk with on the telephone, no matter the distance. As communication cost decreased still further, it supported a rapidly expanding and more complex society, which in turn fostered even more societal dispersion. It was increasingly apparent that communities dispersed as the cost of communication decreased. Here was early evidence, now fully proven in the Social Age, that productivity doesn’t always require face-to-face interaction.

Rather than revolutions, the first and second Industrial Revolutions can perhaps better be thought of as the evolution of technologies from earlier, less-efficient—and less-effective—predecessors. Much like Darwinian organic evolution, technology progresses through a natural selection process in which those traits most useful to society are propagated and further enhanced with more innovations. Incremental advances occur as less-efficient systems are abandoned or improved—the telegraph becomes the telephone, and the stage coach becomes the railroad.

Technologies that evolve and constantly provide increased value will survive. Each technical advance is driven by an increased need for efficiency and effectiveness, which in turn is driven by the understanding that the delivery of increased value results in increased value received—revenue and profits. Henry Ford recognized the incredible power of innovation to drive profit:

We regard a profit as the inevitable conclusion of work well done. Money is simply a commodity which we need just as we need coal and iron. If money be otherwise regarded, great difficulties are inevitable, for then money gets itself ahead of service. And a business that does not serve has no place in our commonwealth.[4]

In some cases, the evolution of technology is so dramatic that little remains of the foundational idea on which the technology is based. But there are times when even a small incremental change can lead to an innovation with tremendous social and economic impact. Modern electricity represents such an incremental change.

Three main players are on stage for this historic moment in 1887. The first is Thomas Edison, the visionary “Wizard of Menlo Park,” with his 1,000+ patents. Next is the insightful businessman George Westinghouse, the chief rival of Edison, best known to that moment for his invention of a revolutionary air brake system still in use on trains today.[5] And last is Nikola Tesla, the brilliant young inventor with the photographic memory and a reputation for efficiency in the inventive process.

Edison made great progress leveraging direct electrical current (DC). With DC, he created a collection of electric appliances and the first light bulb, all of which had lasting impact on the world. But DC was inefficient and difficult to transport over long distances. It was Tesla’s ingenuity that transformed DC to alternating electrical current (AC) and enabled electricity to be transported over long distances at low cost, establishing our current modern electrical grid.

It was a small change, but AC vastly improved electrical power. George Westinghouse bought Tesla’s AC patent, and together they created the technology that transformed modern life, which even today is used to power the world. Businesses became more efficient and mass production costs were reduced dramatically with a new electric utility enabled by the AC technology. Powerful mass communication devices such as the radio would soon become a reality.

Like electricity, radio also evolved incrementally through many small but significant steps. Through the groundbreaking 1897 work of Guglielmo Marconi—known as the “father of wireless telegraph”[7]—telegraph was no longer bound by copper wire. Leveraging the electromagnetic waves theory first postulated by James Clerk Maxwell in the middle 1800s, Marconi transmitted telegraph through the air and paved the way for the next revolution in mass communication—the radio. In 1907 Lee de Forest created audion, a feedback amplifier and oscillator that used Marconi’s wireless telegraph principles to send the human voice across the airwaves for the first time.[8]

Ten years after Lee de Forest’s audion, the radio became a household fixture. The radio helped keep the nation together through the Great Depression and two world wars. Such a means of mass communication was without precedent in human history. Radio was affordable to most Americans, and listening soon became a national pastime.

Perhaps the greatest validation of the radio as the primary means of mass communication came immediately after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. Within 24 hours of the attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (Figure 1.2) was heard on the radio delivering his most memorable speech to Congress about “[the] date which will live in infamy.”[9] This was a historic moment because a U.S. president used radio to gain immediate access to an entire country and inspire them to work together to win the war. The low cost of the communications medium made Roosevelt’s appeal available to the broadest possible audience in real time.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, National Archive

In our consideration of the Social Age, Roosevelt’s example is also instructive. Roosevelt found that the best method of effective organization was to speak to the largest number of people possible over the least expensive medium. He was leveraging the social aspect of radio to create an unprecedented sense of unity in the country and support for the war. As Roosevelt demonstrated, and as we’ve seen repeatedly in the Social Age, the greatest value of low-cost communication is its capability to enhance the effectiveness of crowds and organizational efforts across a wider range of communities.

The radio also dramatically compressed the time required for news to be distributed, and at a much lower cost than newspapers or other traditional methods. The invention of the television followed with even greater communication power. In fewer than 30 years—from 1950 to 1978—households owning televisions in the United States rose from 9 percent to 98 percent.[11] Television is a prime example of the way communication cost has steadily decreased in the modern era, as illustrated in Figure 1.3.

Although television was an early step in the Information Age, the advent of computers—particularly personal computers—marked the high point of the Information Age and laid the foundation for the Social Age. Beginning in 2000, we entered the transition from the Information Age to the Social Age as fully enabled and “smart” electronic networks were rapidly becoming populated with social services and tools such as Classmates and YouTube. Mass communication up to that time was essentially a unidirectional medium. But now, for the first time, meaningful two-way communication was possible on the Web, using Web 2.0-enabling technology that arrived on the scene around that time.

Social networking tools such as wikis and blogs are possible only because of a bidirectional communications technology known as the Semantic Web. The Semantic Web created the concept of a smart document that is aware of its own content via Extensible Markup Language (XML) tags. A host of technologies support this trend including Resource Description Framework (RDF), Web Ontology Language (OWL), and other XML extensions. For example, if you update a page that is content-aware, the update will be reflected in other related sites. Simply put, when someone changes something on a content-aware Web site “A,” Web sites “B,” “C,” and “D” have their content dynamically updated as well.

The Semantic Web innovations, combined with two-way communication-capable web pages, such as wikis, blogs, and other social networking tools, created a completely new way to get organized, provide information, and collaborate. In turn these changes created even greater efficiencies and propelled social tools to broad acceptance by the general public.

These changes are also happening inside the protected environment of the corporate firewall. For the first time, lower-cost Internet communication and two-way web technologies have enabled businesses to collaborate and leverage large and diverse internal and external communities through social networking services.

Social networking is a critical long-term shift of the Internet revolution and is the primary catalyst of the Social Age. Suddenly, smart content and two-way communication empowers the individual to be heard in a meaningful way. Each person’s opinion carries the same weight as fellow collaborators. Everyone’s credibility is enhanced and his or her opinion is important. Particularly in decision making, the opinion of the crowd is now vital to final outcomes.

As social networking tools gained popularity, the world became increasingly instrumented. Through radio frequency identification (RFID) tags, and other technologies, the previously insensate world suddenly got “smart.” New two-way communication devices can sense human activity, monitor supply chain workflow for bottlenecks, and even analyze weather patterns, making our world smarter and more efficient.

In comments to the Council on Foreign Relations in November 2008, IBM’s CEO Sam Palmisano picked up on this theme. “The world will continue to become smaller, flatter…and smarter,” he said. “We are moving into the age of the globally integrated and intelligent economy, society and planet.” He concluded with a challenge: “The question is what we are going to do with that?”[12]

This is certainly a question we do well to ask ourselves, and one we address in more detail in Chapter 2, “Social Age Organizations.”

As we’ve seen with earlier innovation, the adoption of Social Age technology is accelerating proportional to the decreasing cost of communications. In many ways social networking is following a short, steep pattern of growth reminiscent of other recent transformational technologies such as the personal computer (PC).

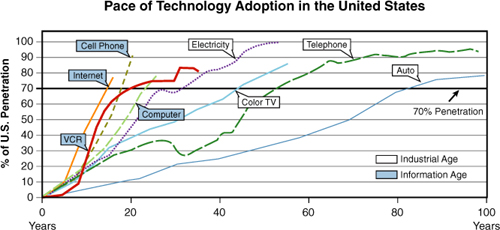

Another example of such growth is the cell phone, which achieved 70 percent market penetration in only seven years. Even with a recession in 2008, the worldwide penetration of cell phones continues to grow at an unprecedented rate. Emerging regions such as Africa and Asia drive much of this increased demand with approximately 250,000 cell phones shipped to those regions in the first quarter of 2008. By comparison, television took nearly 20 years to reach 70 percent penetration. Industrial-Age automobiles took even longer to reach comparable acceptance—more than 100 years.

As each new technical innovation reaches the marketplace, the speed with which it is adopted becomes shorter and shorter. The acceleration of technology adoption has been caused by better communication and increased standardization, which ultimately leads to a lower cost of technology. In this way innovation creates a virtuous cycle—incremental improvements generate lower cost of production, which in turn leads to increased adoption and greater value to society.

By using the assembly line, Henry Ford was among the first to leverage the cost efficiency available through standardization. Perhaps the best illustration of Ford’s philosophy of standardization was his decision to offer his Model T in “any color, as long as it’s black.”[13] More importantly, Ford understood the critical necessity to establish his technology with early adopters before any of his competitors. Ford leveraged the assembly line to lower cost of production that, in turn, lowered the cost of the Model T, making it among the most affordable cars of its time. Early adopters of the Model T drove strong growth and exceptional profitability for Ford, which encouraged competitors to enter the market using similar standardization and assembly line practices.

The Model T is an excellent example of the way early adopters drive a steep demand curve for new technology, which is the part of the adoption cycle with the highest profit margin. Although the initial penetration of the automobile market by early adopters was fast, overall market penetration didn’t achieve the 75 percent mark for 125 years. Today, 75 percent market penetration can be reached with new technology in only a few years, as illustrated in Figure 1.4.

As Ford demonstrated with the Model T, timing is everything to win in any new market. Ford not only reaped the profitable benefits of being first to market with his automobile, he was also the first to transform manufacturing processes with his new assembly line production approach. The result was a standardized product that many could afford, which ultimately led to the commoditization and mass adoption of the automobile. Ford and other entrepreneurs from earlier eras had at their disposal only unidirectional communication such as radio and television to advertise their products. In the Social Age, however, rapid market penetration and adoption of new technology happens much more quickly, and success increasingly depends on effectively marketing to social networking communities.

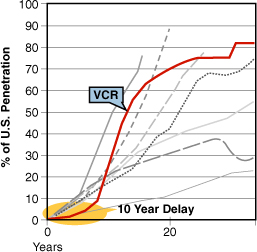

For an example of the dangers of failing to standardize, we need look no further than the competitive battle that raged in the mid-1970s between Sony Betamax and the VHS format of video recorders. Broad acceptance of the VCR was hindered primarily through a lack of standardization. Betamax and VHS were offered simultaneously, dividing the market for ten years (see Figure 1.5), and causing many consumers to delay their buying decisions—no one wanted to get stuck with obsolete technology! As we witnessed recently in the brief, two-year battle between Toshiba HD DVD and Sony’s Blu-ray format,[15] such conflicts are quickly resolved in the Social Age. Social networking tools promote conversations about new technologies across a wide community. These conversations quickly result in a consensus about the superior technology, leading to standardization and broad acceptance.

Importantly, history demonstrates that standardization also quickly leads to commoditization. As standardization is achieved, economies of scale drive costs lower, which in turn further propels adoption of the technology. Commoditization then leads to rapid global acceptance. Faster and lower-cost communication further accelerates the adoption of standardized technology. Two technologies that have commoditized recently—both within the context of fast, low-cost communication—are the personal computer and the cell phone, as demonstrated by their parabolic growth curves in Figure 1.4.

The cell phone is perhaps the most current example of the way low-cost communication has created a massive adoption of technology, which has benefited the Social Age, offering an additional medium of communication. In addition to low cost, the enthusiasm for cell phones is driven by several factors, including its highly customizable design, or its plasticity. From personalized games to ring tones, cell phones can be tuned to communicate any way their owners want. This plasticity will soon lead to cell phones becoming the primary means for collaboration and communication in the Social Age.

With new sensors embedded in cell phones, even credit cards as we know them might become obsolete, using applications such as e-wallet, an IBM-patented technology. E-wallet enables instantaneous connection with credit card companies, banks, and other payers from a cell phone, simplifying the point of sale process.[16] Further transparency for mobile device users becomes available as they enable sensors that are context-aware. By always knowing where their users are, and communicating that information to others, mobile devices will essentially become social coordinators and electronic proxies for their owners.[17]

In many ways, the Internet revolution was just the beginning; the real revolution, taking place now, is social networking. As we discuss in the following chapters, social tools such as wikis, blogs, tags, interactive games, and ratings that enable folksonomies[18] (among others) are at the heart of the Social Age and represent a key value proposition for your business.

The speed with which social networking tools have been embraced is stunning. Every month millions of people and businesses are jumping to get connected, whether to satisfy a basic social need or to sell their products through this powerful new “electronic word of mouth.”

As recently as 2002, blogs were considered arcane technology used mostly by geeks to share their thoughts and witticisms. But the plummeting cost of communication and pervasive social technology has in many ways encouraged the soaring adoption of blogs and other social networking tools in just a few years.

Today, a tsunami of blogs comes from all levels of expertise, from professional writers to rank amateurs. People can’t get enough of social tools. Seemingly overnight there are a host of social tools available online, including MySpace, Facebook, Friendster, Orkut Windows Live, Classmates, Cyworld, Bebo, Hi5, and others.[19] Like-minded enthusiasts can connect on 24hTennis, Taltopia, Travellerspoint, Librarything, GoodReads, MyArtSpace, CakeFinancial, and others.[20] You can celebrate your heritage on BlackPlanet, MiGente, Geni, and many others.[21] While you’re at it, why not expand your business network with LinkedIn and Plaxo?[22] All these relatively new sites, attracting tens of millions of visitors each day, are the direct result of the revolutionary changes of the Social Age.

An exabyte is one quintillion bytes—a billion gigabytes. It seems like only yesterday, just when we had learned how many bits were in a byte, that we were suddenly asked to learn about megabytes and gigabytes. Now we need to keep track of exabytes!

IDC said that as of 2007, the digital universe was 281 exabytes in size.[23] IDC predicts that the digital universe will reach nearly 3,000 exabytes by 2010 (3,000,000,000,000 gigabytes). This is actually a conservative estimate, which excludes specialized data from scientific experiments such as the Large Hadron Collider and digital telescopes that generate several exabytes per week.[24]

A computer-age pioneer, Frederick Brooks, Jr., looked back with nostalgia on his early, slower-paced years in the industry and forward with anticipation of the bright future ahead:

When I was a graduate student in the mid-1950s, I could read all the journals and conference proceedings; I could stay current in all the disciplines. Today my intellectual life has seen me regretfully kissing subdiscipline interests goodbye one by one, as my portfolio has continuously overflowed beyond mastery. Too many interests, too many exciting opportunities for learning, research, and thought. What a marvelous predicament! Not only is the end not in sight, the pace is not slackening. We have many future joys.[25]

Brooks penned those words in 1994. Much has happened since then. Not only has the pace “not slackened,” but an exponential acceleration in knowledge has forced us to rethink almost everything about the ways we learn, interact with each other, and get our jobs done.

The video sharing Web site YouTube.com has a number of provocative five- to six-minute videos about the pace of change in our technological world, all of which were apparently inspired by 2007’s Shift Happens (also known as Did You Know?).[26] Originally produced for a teacher’s conference to spark discussion about trends in education, Shift asks a series of questions about the state of world culture and demographic trends.

Shift points out, for example, that the first commercial text message was sent in 1992, and in 2006, the number of text messages sent each day exceeded the total population of the planet. In 2006, there were 3,000 books being published daily. The amount of technical information was doubling in 2006 every two years, and by 2010, technical information is expected to double every 72 hours. In 20 years or so, this means a college freshman studying technical disciplines will learn things that will likely be obsolete by the time he or she graduates.[27]

Social networking certainly contributes to this mind-numbing growth of information, but ironically, social tools are also the best way to deal with this explosion.

So what does all this mean as you consider the impact of the Social Age on your life and business? History has shown that major revolutions—in technology and in politics—create disruption and uncertainty as the old order is threatened and at last replaced by the new. Smart businesses see this disruption and uncertainty as an opportunity. They rush to bring innovations and value propositions to corporations, to the government, and to society at large. Disruptive innovations and solutions confront lower barriers to entry during times of uncertainty and often serve to facilitate the establishment of a new social order.

• The main thesis of The Social Factor is that three forces led to the revolution we call the Social Age: information overload created during the Information Age, standardization of technology that has commoditized key conduits of communication such as pervasive devices like cell phones, and low-cost two-way Internet communication including wikis and other social networking tools.

• Technology revolutions are more appropriately thought of as iterative evolutions from less-effective and less-efficient predecessors to solutions that provide more value to society. An example is the telegraph evolving into the wireless telegraph and eventually into the radio.

• Faster and lower cost of communication combined with standardization leads to more rapid market penetration of technologies.

• The enormous social networking capabilities of the cell phone are transforming it into a genuine social extension for the user.

• Social networking tools are an excellent way to manage the overwhelming flood of information generated by the fast pace of our society.