The service economy we see all around us is the result of a 300-year socioeconomic revolution. In Chapter 1, “Dawn of the Social Age,” we traced the path that transformed a rural society, driven by an agricultural economy, into a manufacturing society driven by the Industrial Revolution. This revolution happened through massive economies of scale, which were the results of automation and standardization.

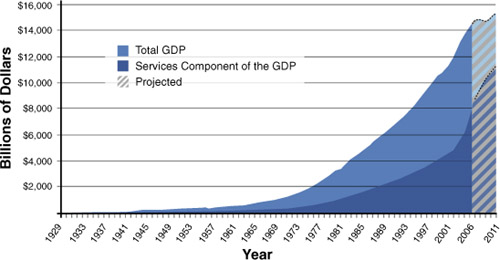

These industrial efficiencies opened opportunities to create and offer services that provided higher economic returns than those obtained through manufacturing. Services soon became both an important differentiator and a key growth element for many businesses. In the United States, more than 60 percent of the population today works in service-related businesses, and this trend shows no signs of slowing with a GDP services component that is expected to reach almost 80 percent by 2011.[1] World GDP, which was approximately $52 trillion in 2008,[2] is expected to grow to $82.5 trillion by 2013[3] with continued growth in the services component. In fact, the services component of the GDP has grown steadily since just after World War II (see Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1. The service component of the GDP has become more than 43 percent of the total U.S. GDP in the last 40 years. Data from the U.S. Department of Commerce.[4]

In the Social Age, services businesses stand to gain the most from an environment that will be dominated by innovations in services models and offerings. In this chapter, we explore the financial implications that are upon us in the Social Age and the ways social networking and technology adoption are affecting GDP. We see how leveraging social networking tools within the organization and using external social networks as a powerful new marketing channel can invigorate services businesses to grow and increase their market share.

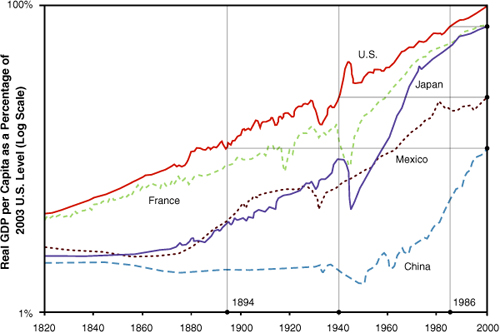

Even in the face of a linear acceleration in technology adoption, the GDP of developing countries continues to lag the United States. Countries such as South Korea, Japan, Singapore, New Zealand, and Australia, for example, have surpassed U.S. rates of cell phone adoption, but they still lag in per capita GDP growth.[5]

In an interview for this book, Harvard University professor Diego Comin talked about the wealth of data he’s gathered that demonstrates a correlation between technology adoption and GDP growth. But although we might expect there to be a direct correlation, Dr. Comin’s research demonstrates that GDP grows more slowly than the rate of technology adoption.[6]

Other factors must therefore be at play here as well, and I believe at least part of this divergence can be explained by the degree to which an economy is driven by social networking. The effect of social networking between organizations within a country was examined by Dr. Effie Kesidou[7] in her study, “Local Knowledge Spillovers in High Tech Clusters in Developing Countries.” Dr. Kesidou defines local knowledge spillovers as “the externalities that are the result of the inability of one firm to retain the economic returns of its innovation activities.”

For example, if company A creates an innovation but cannot protect the innovation through patents or sufficient secrecy, the idea might “leak” to company B, which, in turn, can benefit from it. Dr. Kesidou demonstrates that the wider and stronger the social networks between companies, the higher the likelihood of knowledge spillovers, which ultimately benefit the country in which the companies are located. These spillovers accelerate the benefits gained from the new technology, which has an aggregative effect that increases the country’s capability to profit from adoption of the new technology.

Local knowledge spillover is one of the reasons high-tech companies gravitate to the same geographical area. Here in the United States, Silicon Valley in the West, or the 128 corridor in the Northeast have been traditional technology magnets. These tightly knit regions not only benefit the local economy, at least partially due to local knowledge spillovers, but they also drive the GDP of the country.

Local knowledge spillovers are a powerful indicator that social networking serves to efficiently disseminate and propagate tacit knowledge, which accelerates the use and adoption of new technologies. Dr. Kesidou’s findings offer compelling evidence that a country that fosters collaboration and social networking between industries and organizations (including universities), and with international companies, will accelerate the pace of technology adoption. As a by-product of increased technology adoption, greater business advantages are generated, resulting in GDP growth.

There appears to be a strong correlation between the social networking capacities of a country and its capability to realize efficiencies and opportunities derived from new technologies. Countries such as China and Mexico, which have made exceptional efforts to adopt new technologies, are nevertheless still lagging in their GDP, perhaps in part for this reason (Figure 11.2).

The tremendous acceleration of communication technologies in the Social Age has been indispensable to the growth of economies around the world. This acceleration has also created new phenomena that are the result of nearly instantaneous dissemination of information. As we explore one of these phenomena in the next section, in a way we’re returning to concepts first suggested in Chapter 9, “Social Brain and the Ideation Process,” about the workings of the human brain. As we said, when the brainpower of many people is joined to foster innovation, the results can be amazing. But group thinking, or perhaps we should say, “group enthusiasm,” can also cause headaches—or opportunity—for your innovation efforts, depending on the way you manage it.

If you’ve seen news reports of lines of people stretching around the block waiting to buy the latest gadget, you have an idea what this section is about. Although we’re each individuals, with individual thought processes, our various communities—work, home, neighborhood, online social networks, the broader culture—heavily influence us and our perceptions.

Traditional media and our social networks combine into a “crowd perception” that surrounds us and constantly influences our subconscious. In fact, our values and judgments might not be as original as we’d like to think. This crowd perception also drives unrealistic expectations about new innovations. These overly enthusiastic expectations are often referred to as the “hype” associated with a new technology. It is crucial for a business to recognize the reality and influence of hype if it is to be successful in its innovation efforts.

The most recent example of hype is probably the dot-com bubble and the subhypes that sprang up around a host of Internet companies, many of which quickly became worth billions of dollars (on paper) and yet had not generated a single dollar of profit. With a mighty crash the hype ended and reality set in, as the dot-com boom turned to bust.

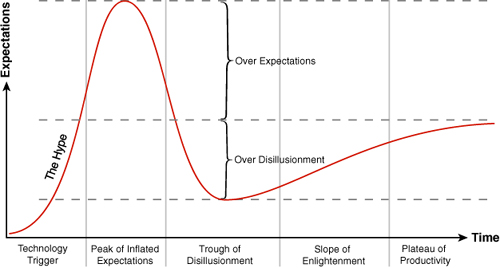

Although stunning in its scope, the dot-com boom and bust represented the normal “perception cycle” of communities who adjust their expectations after going through a thoughtful evaluation process. The hype cycle model was developed by Gartner in 1995 to help its customers distinguish between true value and mere hype. In 2008, the concept was published by Jackie Fenn and Mark Raskino in their landmark book Mastering the Hype Cycle: How to Adopt the Right Innovation at the Right Time.[9]

Fenn and Raskino demonstrate that the introduction of a hot, innovative product to market triggers high expectations. Early adopters tend to overestimate its value and consequently create considerable hype around the innovation. A period of disillusionment follows, but eventually a rebound occurs. This step is the “slope of enlightenment” period, and is based on more realistic expectations; here customers begin to properly judge the true value of the innovation (Figure 11.3).

The Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) in the late ‘90s is a recent example of the hype cycle. Multiple failed attempts with early operating systems and cumbersome, nonstandardized interfaces quickly turned excitement about the PDA to a period of disillusionment. The PDA’s astronomical expectations and hype actually brought down many companies during the 2001 recession. The PDA technology eventually evolved into today’s smart phones. Now, there are nearly four billion cell phones subscribers worldwide, claiming a staggering 61 percent market penetration as of 2008.[10]

Helping people get organized was the original intent of the PDA, but millions of smart phones have demonstrated that low-cost communication and community collaboration are primary drivers of new technology in this area. The faltering start of the PDA merely laid the foundation for a better solution—the smart phone, whose primary value is to connect with others in a more natural and convenient way.

The classic hype cycle curve in Figure 11.3 reveals the overly enthusiastic expectations at the beginning of the cycle triggered by the innovation. The disillusionment period follows, before enlightenment, when the true value of the innovation is realized. Expectations finally plateau, and the hype cycle curve flattens out as the technology matures.

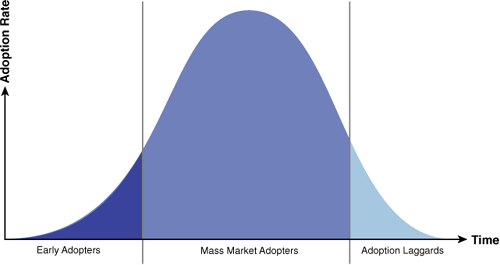

People and companies—which are actually just groups of people—are heavily influenced by the hype around a new technology and often jump in, hopeful of gaining an edge on the market. As we consider the hype cycle, however, it’s helpful to keep in mind that behind the volatile and sometimes dramatic hype cycle is the somewhat less volatile adoption cycle. In Chapter 10, “Social Innovation,” we reviewed the adoption cycle up close through the Technology Adoption Program (TAP). The adoption cycle identifies essentially three different personality types, each of which takes a slightly different view and approach to new technologies. These three types can be broadly categorized as early adopters, mass market adopters, and laggard adopters.

Early adopters, although being relatively fewer in number, tend to be a bit more daring, while at the same time making their thoughts and feelings known (sometimes loudly) about new technology. They’re willing to collaborate with innovators to improve new technologies. They publish their enthusiasm and their criticisms on their blogs, often greatly influencing others.

As a product evolves and improves to satisfy the needs of a wider market, adoption increases. After some time the pressures of the market and standardization lead to the commoditization of the innovation, and mass adoption takes place. Technology laggards finally begin adopting the new technology as a substitute for earlier, less-efficient products. This natural process of technology adoption traces a normal bell curve shape[11] (Figure 11.4).

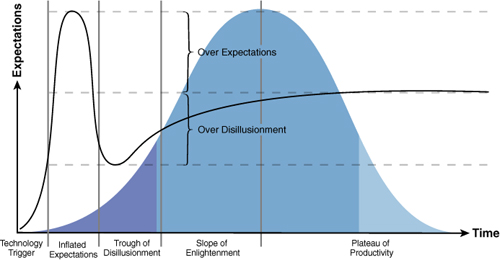

Business strategists need to understand that there is overlap between the hype cycle and the adoption cycle. By failing to properly manage expectations about a new technology, the hype cycle can get out of control, creating astronomically unrealistic expectations about the new technology, and potentially deepening the disillusionment channel that inevitably follows. This phenomenon is more easily understood when we combine the dramatic extremes of the hype cycle with the natural adoption curve.

Most of the hype for a new technology is driven by early adopters, as illustrated on the left side of Figure 11.5. They act as sort of the main booster rocket, getting the innovation off the launch pad. Because they are often perceived as experts in their field, early adopters attract a lot of attention, and their opinions—in blog postings, magazine articles, or other media—carry relatively greater weight. If not properly managed, however, early adopters can create inflated expectations about the technology, leading to an uncomfortable period of disillusionment and possible dissatisfaction.

This is a good reason to establish a well-managed innovation program. By segregating early adopters from mass market adopters, you can essentially calibrate expectations during the critical early stages of new product introduction. As you introduce the product into the broader audience of mass market adopters, the capabilities and limitations of the product are fully known, and the disturbing disillusionment period is left behind.

This analysis of the hype cycle is important for another reason. If your company is considering a new technology for internal use, it pays to understand where that technology is in the hype cycle. Perhaps you’ve identified a technology that will be perfect to solve one of your business challenges, or that you believe will be well received by your customers. It’s a hot technology. The trade magazines have been running the inventor’s picture on their front covers, and you heard that the company across town is installing version 1.0 for its engineering teams.

CEOs and CIOs are, by definition, professional risk managers. They know there’s a time to jump in and a time to take a step back. Understanding the hype cycle can help. In general, the best time to adopt a new technology is not during the first leg of the hype cycle. Instead, that’s usually the time to take a step back and watch for the beginning of the period of disillusionment. During the disillusionment period, the market tends to over-penalize companies for any shortcomings of the product or the new technology. This provides the opportunity to adopt the new technology at a lower cost and with more realistic expectations.

You know you need to transform your business, and it appears a new technology might be the way to do it. But is it really? Successful implementation of a new idea to transform your business requires careful consideration and analysis.

Be sure to evaluate the return on investment (ROI) and Pre-Tax Income (PTI) not only of the technology under consideration, but also of possible alternatives. To maximize your ROI and PTI on new ideas or products, take into consideration the timing and maturity of the market to receive you innovation. Great ideas ahead of their time don’t produce good ROI.

To maximize the chances for the success of a transformation or innovation project, plan for an assessment period to simulate multiple business scenarios. Simulating various business scenarios on a spreadsheet is far less expensive—and stressful—than watching your Profit and Loss statement suffer because of ill-conceived, real-world experiments. Give yourself enough time for the transformation, and protect your innovation project during the fragile development process and early adoption cycle. Don’t let innovations get killed before they have a chance to prove themselves to the market. Ensure that your innovation process evaluates new ideas in a way that takes into consideration future market conditions, and ways they could lower cost of operations.

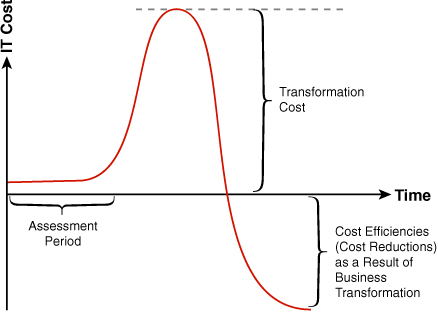

Ultimately, the analysis of a new technology should demonstrate that the cost efficiencies gained will outweigh the overall cost of transformation (Figure 11.6).

The Social Factor is about this tremendous revolution we are a part of—a revolution of low-cost communication and unprecedented social connections. This revolution is possible only because of the powerful and amazing Social Age tools at our disposal. For the users of social networking tools, they now wonder how they were ever able to live without them. We’ve offered many examples of the advantages and opportunities available with social networking. But if you’re still not convinced, consider the case of a relatively unknown U.S. senator from the state of Illinois, who only a few years ago was laboring in the south side of Chicago as a community organizer.

From his days in Chicago, this young senator understood something very powerful. He understood that when people got organized at a local level, about issues of local interest, they are eager to work together. And he understood something else as well—he understood that we are living in the Social Age. He took what he knew about getting people organized at the local level, and combined it with what he knew about social networking, and he created a presidential campaign unlike any ever seen before.

Previous presidential campaigns (most notably that of Howard Dean in 2004) provided early and powerful evidence that the political game had changed. If someone hoped to compete for the highest office in the land, a comprehensive Internet strategy was not just an option, it was a necessity. And it was Howard Dean’s IT team at Boston-based Blue State Digital that created the framework of the socially networked locomotive that became the Obama campaign. Using Dean’s Internet campaign machinery as its foundation, Blue State Digital forged a completely new strategy that made use of every possible social networking tool to reach the electorate.

When I interviewed Blue State chief technology officer Jascha Franklin-Hodge for this book, he provided incredible insights into the Obama campaign. He told me about the way Obama used social networking to help empower his supporters. He said that Obama realized democracy worked best when you have high participation from people, and social tools are the best vehicle to accomplish that.

“Early on,” Franklin-Hodge said, “the emphasis in the campaign was on traditional fund-raising, using the Obama campaign Web site. But after Super Tuesday—when more than half the delegates were committed—it became apparent that Obama had a strong emotional appeal that carried him to a virtual tie with Hillary Clinton in those crucial primaries. For much of 2007, conventional wisdom held that Clinton would easily win the nomination. For ten years Clinton had been building the most powerful political machine anyone had ever seen. But here was Obama, really connecting with the average voter. We knew we had to tap into the excitement of those voters to help drive the campaign.”

Franklin-Hodge paused briefly, and said with a laugh, “And we only had eleven months to do it.”

Franklin-Hodge went on to explain the way Blue State used social networking to harness “local power” in the national presidential campaign to maintain momentum and build excitement right up to the general election. Rather than using social tools merely to fund-raise, Blue State quickly realized Obama was winning the money battle, so the focus shifted.

Instead of an emphasis on fund-raising, Blue State began to build the social networking tools needed to empower individual supporters. For example, Obama volunteers used the resources on the Obama Web site to establish local organizations. These local organizations might have been as few as three or four people, or literally hundreds of people. The Web site allowed supporters to enter their ZIP code, and lists of local Obama organizations in that area (and upcoming local campaign events) were offered. If there wasn’t a local organization, the Web site provided the tools to establish one. (By the date of the general election, there were more than 35,000 Obama organizations across the country.) Local events such as a county fair could be used as the ad hoc gathering spot for local supporters. The word could go out through the local social network to stop by the Obama table at the fair. Parties were also organized by local organizations in which the excitement and momentum could be sustained.

On the Obama Web site there were podcasts of speeches and streaming video to view or download. And most powerfully, there was a nearly seamless connection not just to the individual supporter who signed up on the Web site, but also to everyone in his or her e-mail address book. That’s right—the Obama campaign offered the option to open your address book to help you reach additional supporters.

“You could provide access to your iPhone address book,” Franklin-Hodge said, “and you could download an application that analyzed your address book by area code. As the campaign progressed, races were tight in certain states—the battleground states, such as Ohio and Pennsylvania. This application essentially searched your address book and presented you with contacts in your address book who lived in battleground states and then asked you to call them to persuade them to vote for Obama.”

In addition to giving you a list of your friends and colleagues in battleground states to call, the application also suggested a few bullet points to highlight while having the conversation.

“We realized that you can only tell people to give money or do something so many times,” Franklin-Hodge said. “They need to make their own decisions about the best way to campaign. We provided the tools they needed and then got out of their way. Most people, for example, weren’t interested in putting an Obama widget on their Facebook page. But when they posted an activity they did on behalf of the campaign, that activity appeared as a news item on the Facebook account of their friends. This low-touch model offered powerful synergies for the campaign.”

“On the one hand,” Franklin-Hodge said, “we were establishing something of a directed anarchy by giving supporters the tools and getting out of their way. On the other hand, we were able to close the data loop very effectively and efficiently. We provided mobile applications the supporters could use to gather data about potential voters as they campaigned. That data could easily be uploaded to the campaign database by a supporter, essentially giving us a street-by-street reading on support for the candidate.”

“Traditionally,” said Franklin-Hodge, “that job was done by a campaign worker staying up until 3:00 a.m., entering all that information by hand into a database. We streamlined and automated the whole process through social tools.”

Not only did the campaign use fresh data to get an accurate snapshot of support as the campaign progressed, they also used that same data to “micro-target” areas where support for the candidate was soft.

The incredible fund-raising efforts of the Obama campaign are well documented, at one point totally more $100 million a month.[12] This success was a function not just of a great Web site, but also of the millions of social connections that were made through each of Obama’s supporters. The campaign demonstrated that a small financial investment in social networking tools provided a national impact and even a worldwide awareness of this young senator from Illinois. Social networking created an exponential multiplier effect that left Obama’s opponents scratching their heads and his critics baffled.

As a relative unknown, he organized the south side of Chicago and gave the people hope. Using social networking he organized his supporters in the 2008 presidential campaign and gave the nation hope. As Obama fulfills his duties as president, he can serve as something of an inspiration to the rest of us, especially to those who still have their doubts about the power of social networking.

Because after all, if it helps get you elected president of the United States, is there anything social networking can’t do?

• There is a direct relationship between technology adoption and GDP growth. The more new technologies are adopted and exploited by a country, the more the country’s GDP grows.

• The service component of the U.S. GDP has increased considerably to become more than 43 percent of the total.

• Social networks, especially across businesses, appear to have a direct relationship to the pace at which a country develops.

• The hype cycle, especially when combined with the adoption cycle, provides valuable insight into the excitement about new technologies and the way you can avoid falling in the hype trap.

• Adoption of social software tends to change peoples’ attitude and helps break silos. Leverage social tools to corral your organization into a common purpose, as the Obama campaign did.