Chapter 3

Where Are the Customers' Yachts?

An out‐of‐town visitor was being shown the wonders of the New York financial district. When the party arrived at the Battery, one of his guides indicated some handsome ships riding at anchor. He said,

“Look, those are the bankers' and brokers' yachts.”

“Where are the customers' yachts?” asked the naïve visitor.

—Fred Schwed, Where Are the Customers' Yachts?1

If you've never read an investment book before, chances are you've never heard of index funds. Financial advisors rarely like to discuss them. Index funds are flies in caviar dishes for most financial advisors. From their perspective, selling them to clients makes little sense. If they sell index funds, they make less money for themselves. If they sell actively managed mutual funds, financial advisors make more. It really is that simple.

Most expats, however, should be interested in funding their own retirement, not somebody else's.

The term index refers to a collection of something. Think of a collection of key words at the back of a book, representing the book's content. An index fund is much the same: a collection of stocks representing the content in a given market.

For example, a total Australian stock market index is a collection of stocks compiled to represent the entire Australian market. If a single index fund consisted of every Australian stock, for example, and nobody traded those index fund shares back and forth (thus avoiding transaction costs), then the profits for investors in the index fund would perfectly match the return of the Australian stock market before fees. Stated another way, investors in a total Australian stock market index would earn roughly the same return as the average Australian stock.

Global Investors Bleed by the Same Sword

Now toss a professional fund manager into the mix—somebody trained to choose the very best stocks for the given fund. Unfortunately, the fund's performance will likely lag the stock market index. Most active funds do. Regardless of the country you choose, actively managed mutual funds sing the same sad song.

Recall why from the previous chapter. Professionally managed money represents nearly all of the money invested in a given market. Consequently, the average money manager's return will equal the return of the market—before fees. Add costs, and we're trying to run up that downward‐heading escalator.

Consider the UK market. According to a study published by Oxford University Press, “Mutual Fund Fees around the World,” the average actively managed fund in Great Britain costs 2.28 percent each year, including sales costs.2 Regardless of the market, the average professionally managed fund will underperform the market's index in equal proportion to the fees charged.

Ron Sandler, former chief executive for Lloyds of London, reported a study for The Economist, suggesting that the average actively managed unit trust in Great Britain underperformed the British market index by 2.5 percent each year. It's no coincidence that the average UK unit trust (mutual fund) cost British investors nearly 2.5 percent per year.3

You might think that's nothing…a bit like a waiter's tip. But it's more like the tip of an iceberg. Here's an example. A 30‐year‐old investor might have an investment time horizon of 55 years. She would start selling parts of her portfolio once she retires. But she would keep most of the money invested, selling portions of the portfolio each year to cover retirement living costs (see the last two chapters for a full explanation).

If British stocks averaged 8 percent per year over her investment lifetime, an investor paying 2.5 percent per year in fees would earn about 5.5 percent per year after fees. If inflation averaged 3.5 percent per year (that's close to the long‐term developed world average), the investor would earn an after‐inflation return of just 2 percent per year.

Table 3.1 shows how that might look over 55 years. I've compared it to a British stock index (which I'll show British investors how to buy).

Table 3.1 Growth of a £5,000 Lump‐Sum Investment over 55 Years

| British Stock Market Index | Actively Managed British Stock Market Fund | |

| Annual Return of British Stocks* | 8% | 8% |

| Annual Fee | 0.10% | 2.5% |

| Annual Return after Fees | 7.9% | 5.5% |

| Real Annual Return after Inflation (3.5%) | 4.4% | 2.0% |

| After‐Inflation Value after 55 Years | £53,394 | £14,858 |

*This isn't a prediction of how British stocks or funds will perform, nor does it predict future inflation. It simply serves as an example of the tyranny of fees.

Not all actively managed funds fall behind their benchmark indexes. But most of them do. The SPIVA Scorecard shows how many disappoint. Let's start by looking at actively managed funds created by US firms. Each fund fits into a different category. For example, some stock market funds hold only US stocks. Other US‐sold mutual funds hold global stocks. Others are categorized as emerging‐market stock market funds because they invest only in emerging‐market stocks.

Table 3.2 shows that over the 10‐year period ending December 31, 2016, the US stock market index beat 82.23 percent of actively managed US stock market mutual funds. The global stock market index beat 84.26 percent of actively managed global stock market funds. The emerging‐markets stock market index beat 85.71 percent of emerging‐market funds.4

Table 3.2 US‐Sold Actively Managed Funds: Percentage of Actively Managed Funds That Failed to Beat the Market over the 10 Years Ending December 31, 2016

SOURCE: SPIVA US Scorecard: https://us.spindices.com/documents/spiva/spiva‐canada‐scorecard‐year‐end‐2016.pdf.

| Index | 10 Years | |

| US Stock Market Funds | S&P 1500 | 82.87% |

| Global Stock Market Funds | S&P Global 1200 Index | 84.26% |

| Emerging‐Market Funds | S&P IFIC Composite Index | 85.71% |

Canadians shouldn't feel smug after seeing these results. Canadians pay the second‐highest investment fees in the world (after the expats who buy offshore pensions). Table 3.3 shows that over the 10 years ending December 31, 2016, the Canadian stock market index beat 91.11 percent of actively managed Canadian stock market funds. Canadian fund managers did even worse when investing in US and global stocks.

Table 3.3 Canadian‐Sold Actively Managed Funds: Percentage of Actively Managed Funds That Failed to Beat the Market over the 10 Years Ending December 31, 2016

SOURCE: SPIVA Canada Scorecard: https://us.spindices.com/documents/spiva/spiva‐canada‐scorecard‐year‐end‐2016.pdf.

| Index | 10 Years | |

| Canadian Stock Market Funds | S&P/TSX Composite Index | 91.11% |

| US Stock Market Funds | S&P 500 Index | 98.28% |

| Global Stock Market Funds | S&P Global 1200 Index | 96.40% |

| Emerging‐Market Funds | S&P IFIC Composite Index | N/A |

For example, during the 10‐year period ending December 31, 2016, the US stock index beat 98.28 percent of Canadian stock market funds that invest in US stocks. Canada's global fund managers didn't do much better. The global stock index beat 96.40 percent of Canadian stock market funds that invest in global stocks.5

The actively managed funds that are sold in Europe were mostly stinkers too. The European stock market index beat 90.41 percent of European actively managed stock market funds over the same 10‐year period. The US stock index beat 97.91 percent of actively managed European funds that invest in US stocks. Table 3.4 shows that the global stock market index beat 98.45 percent of European actively managed funds that invest in global stocks. And (as shocking as it seems) the emerging‐market stock market index beat all of the actively managed European stock market funds that invest in emerging‐market stocks.6

Table 3.4 European‐Sold Actively Managed Funds: Percentage of Actively Managed Funds That Failed to Beat the Market over the 10 Years Ending December 31, 2016

SOURCE: SPIVA Europe Scorecard. http://us.spindices.com/documents/spiva/spiva‐europe‐scorecard‐year‐end‐2016.pdf.

| Index | 10 Years | |

| Eurozone Stocks | S&P Eurozone BMI Index | 90.41% |

| US Stock Market Funds | S&P 500 Index | 97.91% |

| Global Stock Market Funds | S&P Global 1200 Index | 98.45% |

| Emerging‐Market Funds | S&P IFIC Composite Index | 100% |

Over an investment lifetime, beating a portfolio of index funds with actively managed funds is about as likely as growing a giant third eye.

American Expatriates Run Naked

Unlike most global expats, Americans can't legally shelter their money in a country that doesn't charge capital gains taxes. And actively managed mutual funds attract high levels of tax. There are two forms of American capital gains taxes. One is called short‐term, the other long‐term. Short‐term capital gains are taxed at the investor's ordinary income tax rate. Such taxes are triggered when a profitable investment in a non‐tax‐deferred account is sold within one year.

I can hear what you're thinking: “I don't sell my mutual funds on an annual basis, so I wouldn't incur such costs when my funds make money.” Unfortunately, if you're an American expat invested in actively managed mutual funds, you sell without realizing it. Fund managers do it for you by constantly trading stocks within their respective funds. In a non‐tax‐sheltered account, it's a heavy tax to pay.

Stanford University economists Joel Dickson and John Shoven examined a sample of 62 actively managed mutual funds with long‐term track records. Before taxes, $1,000 invested in those funds between 1962 and 1992 would have grown to $21,890. After capital gains and dividend taxes, however, that same $1,000 would have grown to just $9,870 in a high‐income earner's taxable account.7 American expats, as I'll explain in a later chapter, must invest the majority of their money in taxable accounts.

Because index fund holdings don't get actively traded, they trigger minimal capital gains taxes until investors are ready to sell. And even then, they're taxed at the far more lenient long‐term capital gains tax rate.

In a 2009 New York Times article, “The Index Funds Win Again,” Mark Hulbert reported that Mark Kritzman, president and chief executive of Windham Capital Management of Boston, had conducted a 20‐year study on after‐tax performances of index funds and actively managed funds. He found that, before fees and taxes, an actively managed fund would have to beat an index fund by 4.3 percent a year just to match the performance of the index fund.8

Flying parrots will serve you breakfast before a portfolio of actively managed funds beats a portfolio of index funds (before fees) by 4.3 percent over an investment lifetime. Researchers Richard A. Ferri and Alex C. Benke reported in their 2013 research paper, “A Case for Index Fund Portfolios,” that the slim number of portfolios that beat index funds before taxes between 2003 and 2012 did so with an annual advantage ranging between only 0.29 percent and 0.54 percent per year.9 And that's before taxes.

Why Brokers Want to Muzzle Warren Buffett

Most financial advisors wish to muzzle the brightest minds in finance: professors at leading business universities, Nobel Prize laureates in economics, the (rare) advisors with integrity, and billionaire businessmen like Warren Buffett. Brokers make more when experts are mute.

Warren Buffett, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, is well known as history's greatest investor. And he criticizes the mutual fund industry, suggesting, “The best way to own common stocks is through an index fund.”10

Buffett wrote a parable of the money management industry in Berkshire Hathaway's 2006 annual report. It stars a family called the Gotrocks.11

The family owns every stock in the United States; nobody else owns a single share.

Consequently, the family shares all of the revenue generated by those businesses. But instead of harmoniously splitting that money forever, they live up to their name (“got rocks” in the head) by hiring helpers to redistribute those earnings to the family, with the helpers charging the family fees to do so. Those helpers, of course, are brokers, mutual fund salespeople, and financial services companies. Their fees detract from the wealth the Gotrocks are entitled to.

The parable synchronizes with William F. Sharpe's thesis in “The Arithmetic of Active Management.”12 In it, the economic sciences Nobel Prize laureate proves that, before fees, investors in the stock market earn the return of the market, on average. After fees, as a group, they get scalped. Referencing a parasitic industry, Warren Buffett laments, “People get nothing for their money from professional money managers.”13

That's why Warren Buffett instructed his estate's trustees to put his heirs' proceeds into index funds when the great man dies.14

Nobel laureate Sharpe explains it's delusional for most people (and most advisors) to anticipate beating market indexes over the long term. In a 2007 interview with Jason Zweig for Money magazine, he stated his view:

| Sharpe: | The only way to be assured of higher expected return is to own the entire market portfolio. |

| Zweig: | You can easily do that through a simple, cheap index mutual fund. Why doesn't everyone invest that way? |

| Sharpe: | Hope springs eternal. We all tend to think either that we're above average or that we can pick other people [to manage our money] who are above average…and those of us who put our money in index funds say, “Thank you very much.”15 |

Daniel Kahneman, another famed Nobel Prize–winning economist, echoed the sentiment during a 2012 interview with the magazine Der Spiegel:

Merton Miller, a 1990 Nobel Prize winner in economics, says even professionals managing money for governments or corporations shouldn't delude themselves about beating a portfolio of index funds:

In the documentary program Passive Investing: The Evidence the Fund Management Industry Would Prefer You Not See, many of the world's top economists and financial academics voice the futility of buying actively managed funds. But as the title suggests, it's the program most financial advisors will never want you watching.18

Financial Advisors Touting “The World Is Flat!”

Your financial education is the biggest threat to most globe‐trotting financial advisors seeking expatriate spoils. Consequently, many are motivated to derail would‐be index investors from gaining financial knowledge.

Self‐Serving Argument Stomped by Evidence

Here is one of the most common arguments you'll hear from desperate advisors hoping to keep their gravy trains running:

Index funds are dangerous when stock markets fall. In an active fund, we can protect your money in case the markets crash.

This is where a salesperson tries scaring you—suggesting that active managers have the ability to quickly sell stock market assets before the markets drop, saving your mutual fund assets from falling too far during a crash. And then, when the markets are looking safer (or so the pitch goes), a mutual fund manager will then buy stocks again, allowing you to ride the wave of profits back as the stock market recovers.

There are problems with this smoke screen. First, nobody should have all of his or her investments in a single stock market index fund. Investors require a combination: a domestic stock index fund to represent their home‐country stock market (or the country where they plan to retire), a global stock market index fund to provide global exposure, and a bond market index fund for added stability. (Bonds act like portfolio parachutes. They're loans investors make to governments or corporations in exchange for a guaranteed rate of interest.) If the global stock markets dropped by 30 percent in a given year, a diversified portfolio of stock and bond market indexes wouldn't do the same.

Have some fun with self‐proclaimed financial soothsayers. Ask which calendar year in recent memory saw the biggest stock market decline. They should say 2008. Ask them if most actively managed funds beat the total stock market index during 2008. If they say “yes,” you've exposed your Pinocchios. A Standard & Poor's study cited in the Wall Street Journal in 2009 detailed that the vast majority of actively managed funds still lost to their counterpart stock market index funds during 2008—the worst market drop in recent memory. Clearly, active fund managers weren't able to dive out of the markets in time.19

SPIVA published detailed proof. In 2008, US stocks plunged 37 percent. But despite that horrible year, the US stock index beat 64.23 percent of actively managed US stock market funds.20

Global stocks fell 40.11 percent in 2008. Yet the global stock market index still beat 59.83 percent of actively managed global stock market funds during that calendar year.21

Warren Buffett wagered a $1 million bet in 2008, unveiling more damning evidence against expensive money management. A few years previously, the great investor claimed nobody could handpick a group of hedge funds that would outperform the US stock market index over the following 10 years.

Hedge funds are like actively managed mutual funds for the Gucci, Prada, and Rolex crowd. To invest in a hedge fund, you must be an accredited investor—somebody with a huge salary or net worth. Hedge fund managers market themselves as the best professional investors in the industry. They certainly have plenty of flexibility. Hedge funds (according to marketing lore) make money during both rising and falling markets. Managers can invest in any asset class they wish; they can even bet against the stock market. Doing so is called “shorting the market,” where fund managers bet that the markets will fall, and then collect on those bets if they're right.

Buffett, however, doesn't believe people can predict such stock market movements, charge high fees to do so, and make investors money.

Hedge Fund Money Spanked for Its Con

Grabbing Warren Buffett's gauntlet in 2008, New York asset management firm Protégé Partners bet history's greatest investor that five handpicked hedge funds would beat the S&P 500 index, a large US stock index, over the following 10 years. Protégé Partners selected five hedge funds with index‐beating track records (each was actually a fund that contained winning hedge funds within it). But historical results are rarely repeated in the future.

The bet began in 2008. Stocks crashed that year, so it should have been a great year for hedge funds. If the fund managers could have predicted the crash, they would have pulled far ahead. But that didn't happen. In the years that followed, the S&P 500 ran like a Kenyan from a pack of pudgy men.

By January 2017, just one year remained on the bet. Vanguard's S&P 500 Index was up 85.4 percent. The hedge funds were up just 22 percent. In fact, none of the funds of hedge funds kept pace with the S&P 500. The best performing one was up just 62.8 percent.22

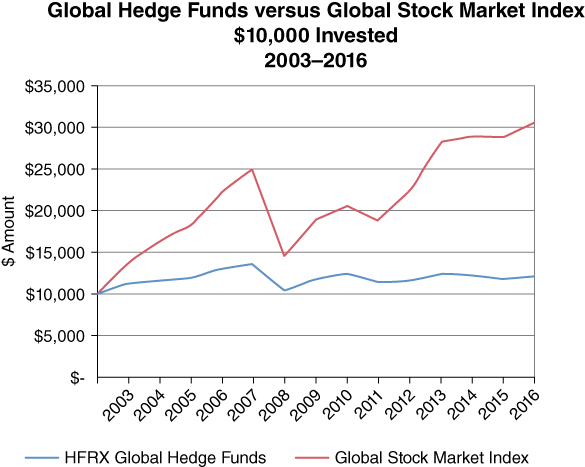

If you've read Simon Lack's book, The Hedge Fund Mirage, these results won't surprise you. He says hedge funds produce horrible returns. Lack reveals that a portfolio balanced between a US stock index and a US bond index would have beaten the typical hedge fund in 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011.23 After his book was published, hedge funds continued to underperform the balanced stock and bond index in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

Between 2003 and 2016, the average hedge fund gained a total of 21.27 percent. That's a compound annual return of just 1.5 percent per year. In other words, your grocery bills rose faster than the typical hedge fund. Inflation beat the typical hedge fund. In contrast, Vanguard's balanced stock market index fund (60% US stocks; 40% US bonds) returned a total of 185 percent. That's a compound annual return of 8.4 percent per year.24

Such a shortfall for the masters of the universe is so great, in fact, that even if the hedge fund managers had worked for free (not charging their usual 2 percent per year plus 20 percent of any profits) a balanced US index fund would have still given them a beating.

The global stock market index also beat them to a pulp. Figure 3.1 shows how $10,000 would have grown in hedge funds between 2003 and 2016 compared to the growth of a global stock market index. The hedge funds would have turned that money into $12,127. The global stock index would have turned it into $30,684.25

Figure 3.1 Hedge Funds Fail to Live Up to Their Hype

SOURCE: Hedge Fund Research Centre; Morningstar.com.

Consider the hedge fund industry's failure to beat portfolios of market indexes. If they can't do it, what chance does your financial advisor have? If your advisor has Olympian persistence, you might hear this:

You can't beat the market with an index fund. An index fund will give you just an average return. Why saddle yourself with mediocrity when we have teams of people to select the best funds for you?

If the average mutual fund had no costs associated with it, then the salesperson would be right. A total stock market index fund's return would be pretty close to average. In the long term, roughly half of the world's actively managed funds would beat the world stock market index, and roughly half of the world's funds would be beaten by it. But for that to happen you would have to live in a fantasy world where the world's bankers, money managers, and financial planners all worked for nothing—and their firms would have to be charitable foundations.

If your advisor's skin is thicker than a crocodile's, you might hear this next:

I can show you plenty of mutual funds that have beaten the indexes. We'd buy you only the very best funds.

Studies prove that selecting mutual funds based on high‐performance track records is naïve. Morningstar is a firm that rates mutual fund performances, giving five stars for funds that have beaten their peers and the comparative index, down to one star for funds with disappointing track records.

According to Morningstar, 72 percent of investors purchased funds rated four or five stars between 1999 and 2009. And why wouldn't they? Whether you're selecting mutual funds on your own or hiring an advisor to do so, going with a proven winner makes sense. But ironically, that's about as smart as sipping seawater.

Star ratings change all the time, and funds that earn five stars during one time period are rarely the top‐rated funds during subsequent years.

Tim Courtney is the chief investment officer of US‐based Burns Advisory. He grew frustrated that so many of his clients insisted he choose actively managed mutual funds with five‐star ratings. After back‐testing the performances of the funds most highly rated by Morningstar during the decade ending in 2009, he found that they usually performed poorly after earning five‐star designations. Not only did most of the funds go on to underperform their benchmark indexes, but they also underperformed the average actively managed mutual fund.26

What if, however, your advisor kept an eye on the star ratings, moving your money from funds that slip in the rankings to newly crowned five‐star funds? Such attention to detail isn't likely, which is good, because it's a terrible strategy.

Hulbert's Financial Digest is an investment newsletter that rates the performance predictions of other newsletters. Studying Morningstar's five‐star US funds from 1994 to 2004, Hulbert's found that if investors continually adjusted their mutual fund holdings to hold only the highest‐rated funds, a total stock market index would have beaten them by 45.8 percent over the decade. In an American expatriate's taxable account, the deficit would be even greater. After taxes, Morningstar's top‐rated funds underperformed the US stock market index by 64.2 percent.27

Historical track records mean little. Even Morningstar's director of research, John Rekenthaler, recognizes the incongruity. In the fall 2000 edition of In the Vanguard, he said, “To be fair, I don't think that you'd want to pay much attention to Morningstar's ratings either.”28

So if Morningstar can't pick the future's top funds, what odds does your financial planner have—especially when trying to dazzle you with a fund's historical track record?

What's maddening about such forecasting attempts is that only 9 percent of funds performing among the top 100 in a given year are able to land there again the following year. The chart in Figure 3.2, courtesy of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), shows the shocking reality.

Figure 3.2 How Many Top 100 Funds Remain in the Top 100 the Following Year?

SOURCES: © 2017 Index Fund Advisors, Inc. (IFA); © Morningstar, Inc. Printed with permission.

The SPIVA Persistence Scorecard gets published twice a year. They look at actively managed funds that are among the top 25 percent of performers. Then they determine what percentage of those funds remains among the top 25 percent of performers. There were 641 US stock market funds among the top 25 percent of performers as of March 2014. By March 2016, just 7.33 percent of them remained among the top quartile. Look for these reports every six months. The data always presents a similar eye‐opening tale.29

One fund company in the United States, however, claims they can beat a stock market index. It's called American Funds. The firm's website displays a championship‐winning chart showing that five of its actively managed funds trounced the S&P 500 between 1976 and 2016. It says, “So the next time you hear ‘You can’t beat the index' consider American Funds' long‐term track record.”30

But it's tougher to beat a market index today than it ever was in the past. Larry E. Swedroe and Andrew Berkin detailed this in their book, The Incredible Shrinking Alpha: And What You Can Do to Escape Its Clutches. Swedroe is a principal and the director of research for Buckingham Strategic Wealth. He's also a prolific researcher.

Swedroe explains in his book that it was easier to beat a stock market index in the past. Brilliant investors found a way to do it. Warren Buffett profiled some of these great investors in his 1984 speech, “The Superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville.”31 The people he profiled didn't just beat the market. They crushed it. Buffett's buddy, Bill Ruane, managed the Sequoia Fund. It averaged 17.2 percent per year after fees between 1970 and 1984. The S&P 500 averaged 10 percent per year. Another one of Buffett's friends, Tom Knapp, ran the Tweedy Browne fund. Between 1968 and 1983 it earned 16 percent per year after fees. The S&P 500 averaged just 7 percent during the same time period.32

What was their secret? They bought cheap stocks based on something called a price‐to‐earnings ratio. Today, we call them value stocks. Back‐tested studies show that many investors who bought value stocks beat the stock market index.

Swedroe respects history's great investors. “They were decades ahead of their time,” he says. “They learned that you could beat the market by picking small stocks or value stocks or quality stocks with increasing price momentum.” But today, most active managers know that. Swedroe says the market has changed. “Today, professional investors account for as much as 90 percent of stock market trading. And each decade, they get better and more sophisticated.”33

Beating the market has always meant the same thing. You have to beat the average stock investor. But because institutional investors manage most of today's money, they now represent what's average. To beat the market, you have to beat the pros.

“Not only do those pros keep getting better,” says Swedroe, “but the gap between the best pros and the rest of the pros is narrowing.” He says it's much like professional baseball. During the first 20 years of the modern era (1903–1921), the average Major Leaguer batted about .250 to .260. Batting averages are similar today. But in the early 1900s, the stand‐out players crushed the rest. Between 1903 and 1921, Ty Cobb batted better than .400 twice (1911 and 1912). Joe Jackson batted .408 in 1911. And George Sisler batted .420 in 1920.

“No one hits .400 anymore,” says Swedroe.34 The players are all well trained, genetically gifted, and coached well. You'll see the same thing in other pro sports. The difference between the best and the rest keeps getting narrower, much as it does with investing.

Now let's come back to the mutual fund company American Funds. On their company website, they say, “the next time you hear ‘You can’t beat the index' consider American Funds' long‐term track record.”35

SPIVA's data says mutual funds that win in the past don't typically beat the market in the years that follow. Larry Swedroe says it keeps getting tougher for actively managed funds to beat their benchmark index. When we look at American Funds' five top performers, we can see that they're a lot like former professional soccer player Diego Maradonna, or former professional tennis player Jimmy Connors. Their days of dominance went out with the Cabbage Patch Doll craze.

In the AssetBuilder story, “Investing with American Funds Is Like Betting on Tiger Woods,” I showed that Vanguard's total stock market index beat these former winning funds over the previous 1, 3, 5, 10, and 15‐year periods ending April 14, 2017.36

It's easy to find actively managed funds that have beaten the index in the past. But neither you nor your advisor will be able to pick the funds that will win over the next year or decade.

If the salesperson's tenacity is tougher than a foot wart, you'll get this as the next response:

I'm a professional. I can bounce your money around from fund to fund, taking advantage of global economic swings and hot fund manager streaks, and easily beat a portfolio of diversified indexes.

Sadly, many investors fall victim to their advisor's overconfidence. Instead of building diversified accounts of index funds, they build actively managed portfolios with yesterday's winners. Sometimes it's a collection of mutual funds with strong historical track records, or a focus on funds from a recently profitable geographic region. The results are often disastrous.

Adam Zargar, a British expatriate in Dubai, had such an experience with an investment representative who sold him a Royal Skandia portfolio. On October 29, 2010, the advisor built a portfolio of funds heavily tilted toward emerging markets, such as India, Thailand, and China. By doing so, Adam's advisor violated investing's golden rule: diversification. Spreading assets among a variety of markets and asset classes increases safety. We shouldn't try to gamble that a recently scorching fund from a specific geographic region or asset class (gold, oil, commodities, etc.) will continue to blaze just because it did so recently.

But that's how most people invest. Adam's advisor was no exception. During the 12 months before Adam's advisor selected his funds, the emerging markets had increased by roughly 25 percent. His World Materials fund had gained 40 percent—before Adam bought it. The advisor chose funds by looking through the rearview mirror, and he failed to diversify. Three years later, Adam's portfolio was in the ditch.37

Nobody makes money every year, of course. But in the three years following the inception of Adam's portfolio in 2010, the British stock market soared 43 percent. Vanguard's Global Stock Market Index (an average of the world's stock markets) rose 32 percent. The US stock market jumped 61 percent.

Despite the globally rising tide, Adam's portfolio lost money. Often, yesterday's hottest geographic sector becomes tomorrow's biggest loser. Futile performance chasing is common. Failing to diversify is common. And most people fall victim.

Adam's advisor was like a boy playing doctor. He didn't understand how financial anatomy works. You might think a professional analyst would have a lot more luck. But that's just wishful thinking.

There are special types of funds called tactical asset allocation funds. These fund managers don't have to stick to a single geographic sector. They don't have to stick to stocks. They might buy bonds one week, stocks the next. They might buy emerging‐market stocks if they think that they will fly. The following week, they could sell them in favor of real estate stocks. These managers are professionals. They keep their fingers on the globe's economic pulse. They try to make skillful trades to reflect where they think the big money will end up next.

One of these guys is Rick Consalves. He cofounded AmericaFirst Capital Management, LLC in January 2007. He's the firm's president and chief executive officer. He also manages the AmericaFirst Income Fund Class A (AFPAX).38

Mr. Consalves is smart. Morningstar categorizes his AmericaFirst Income Class A fund as a tactical asset allocation fund. That means Mr. Consalves isn't just picking US stocks. He's trying to figure out whether US stocks, international stocks, or bonds are set to move. When he makes his decisions, he trades to gain an edge.

According to Morningstar, this fund had 57 percent in US stocks, 35 percent in bonds, and 5 percent in international stocks at the beginning of 2017 (the remaining 3 percent was in cash).39

But it's likely different now because this manager trades a lot. He's always looking for an edge.

If a fund manager traded half of a fund's holdings in a given year, the turnover rate would be 50 percent. If a manager traded every stock within a 12‐month period, the turnover rate would be 100 percent. The turnover, for Mr. Consalves's fund, was a whopping 349 percent in 2016.

Despite all that effort, however, his fund got hammered by almost every index you could find. Since its July 1, 2010, inception to March 27, 2017 (the time of this research), US bonds were 5 percent ahead. International stocks were 35 percent ahead. A balanced stock index (60% stocks, 40% bonds) was 77 percent ahead. And the US stock market index was 109 percent ahead.

Over the five‐year period ending March 27, 2017, AFPAX averaged a compound annual return of 2.7 percent per year.40

I'm not trying to pick on Mr. Consalves. His IQ would probably run circles around mine. But nobody can predict whether US stocks, international stocks, or bonds are going to fly over the next year or more. Mr. Consalves probably knows that. But his fund charges high investment fees from which he earns a fat cut.

Smart investors shouldn't try to move money around, looking for an edge. Morningstar tracks the performance of 316 tactical asset allocation funds. Over the five‐year period ending March 27, 2017, they averaged a compound return of just 3.63 percent per year.41

None of them matched Vanguard's Total Stock Market Index (VTSMX). It averaged a compound annual return of 12.68 percent.42

Tactical asset allocation funds are a lot more show than go. Vanguard's research team wouldn't be surprised. Joseph Davis, Roger Aliaga‐Díaz, and Charles J. Thomas published a report that looked at popular metrics used to predict stock market returns.

They examined price‐to‐earnings ratios, cyclically adjusted price‐to‐earnings ratios, trailing dividend yields, corporate earnings growth trends, and a consensus of predicted earnings growth. They then looked at five different measurements of economic fundamentals, followed by three different multivariable valuation models.

They concluded that “stock returns are essentially unpredictable at short horizons…this lack of predictability is not surprising given the poor track record of market timing and related tactical asset allocation strategies.”43

If a financial analyst can't beat a portfolio of stock market index funds by bouncing money around, your financial advisor won't have a snowball's chance in hell.

Why Most Investors Underperform Their Funds

Chicago‐based Dalbar Inc. compares the results of the US stock and bond market indexes with the profits earned by the average investor. The firm calls this the Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior.

Dalbar claims that between 1987 and 2016, the average investor in US stocks averaged 3.98 percent a year (see Figure 3.3). The US stock market index, in comparison, gained 10.16 percent annually.

Figure 3.3 US Stock and Bond Market Returns versus Investor Returns, 1987–2016

SOURCE: Dalbar Group.

A similar performance gap exists with bonds. During the same 30‐year period, the firm says the average investor in US bonds earned just 0.59 percent per year, compared to 6.73 percent for the US bond index.

Dalbar's data does have its critics. Wade D. Pfau published a 2017 report in Advisor Perspectives to show that the gap between how the market performs and how the typical investor performs isn't as large as Dalbar claims.44 But Pfau doesn't deny that a large gap exists. Morningstar agrees. Each year, Morningstar publishes a report called Mind the Gap.45

Their data shows that the average investor is a bit like Adam Zargar's former financial advisor.

Most people feel good about investing in a market that has recently risen in price, extrapolating that pattern into the future. But stock markets are as unpredictable as the next earthquake. When markets are diving, many investors sell or at least cease to continue buying. By loading up on what's expensive and shunning what's cheap, they buy high and sell low.

Smart investors aren't so silly. Realizing that the markets are random, they buy low‐cost investment products representing the entire global market. They invest regularly, no matter what the markets are doing, and they diversify without speculating. Owning a global representation of investments is much easier than trying to predict the future (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 Financial Advisors Can't Predict the Future

Illustration by Chad Crowe: Printed with permission.

The next time an advisor tries to excite you with a hot fund or economic sector, let him burn his own money—not yours.

If you're countering your advisor's market‐beating claims with proof, he or she might start to panic. When the advisor's desperation peaks, you might hear this:

We use professional guidance to determine which economic sectors look most promising. With help from our professionals, we can beat a portfolio of index funds.

Many of the world's smartest money minds run state and corporate pension funds. I'm not talking about the expensive, dodgy offshore pensions hawked to unwary expats (see Chapter 4 for an explanation of these products). Instead, state and corporate pensions are run at extraordinarily low costs—a fraction of what most retail investors pay. Yet they're still humbled by a portfolio of index funds.

Most pension funds have their money in a 60/40 split: 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds. The consulting firm FutureMetrics studied the performance of 192 US major corporate pension plans between 1988 and 2005. Fewer than 30 percent of the pension funds outperformed a portfolio of 60 percent S&P 500 index and 40 percent intermediate corporate bond index.46 You could have beaten more than 70 percent of pension fund managers with a diversified portfolio of index funds, while allocating less than an hour a year to your investments.

Armed with such knowledge, you should be able to fend off advisors selling inefficient investment products. As an expat, your future may depend on it.

But what if your employer demonstrates ignorance? This is the problem many expats face. Their employers, without understanding the importance of sidestepping unfair financial services options, invite self‐serving sales reps into their establishments. They are often trying to sell offshore pension platforms. They're expensive, charging up to 30 times more than what people could be paying; they're inflexible, penalizing people heavily for withdrawing funds earlier than a predetermined date; and (no surprise here) they pay high‐enough commissions to satisfy a sultan.

How do astute companies prevent their employees from getting leeched? Google's management offers a roadmap.

In a 2008 article for San Francisco magazine, Mark Dowie reported that Google's progressiveness extends far beyond the World Wide Web:

In August 2004, shares of the company were about to go public on the stock exchange. Hundreds of young Google employees would automatically become multimillionaires. But senior vice president Jonathan Rosenberg wanted to protect them from Wall Street's brokers and financial advisors. Company founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page and CEO Eric Schmidt agreed.

They invited experts to speak, including an economic sciences Nobel Prize winner (Bill Sharpe), a legendary Princeton economics professor (Burton Malkiel), and a man named by Fortune magazine as one of the four investment giants of the twentieth century (John Bogle).

All of the experts said the same thing. The financial services reps that were circling Google at the time were after one thing: fees and commissions for themselves and their firms. Each expert told Google's staff to build low‐cost portfolios of index funds instead.47

Unfortunately, few global firms educate employees on suitable investment products. Many employers, without realizing it, push employees into bed with investment providers they should avoid. Signing a deal with a snake in a three‐piece suit has devastating consequences.

Why Do Financial Advisors Lie?

When I was 10 years old, I lived down the street from a boy named James. He was a nice kid. But he used to tell crazy stories. The neighborhood kids and I believed him for a while. But we soon saw the light.

Plenty of kids lie to gain attention. In fact, we probably all did it. But does money, or the thought of money, bring out our inner James? That might be the case with financial advisors.

Harvard economist Sendhil Mullainathan, Markus Noeth of the University of Hamburg, and Antoinette Schoar of the MIT Sloan School of Management published a study called “The Market For Financial Advice.”

They hired actors to approach financial advisors with a fictitious $500,000 portfolio. In some cases, the portfolios were made with low‐cost index funds. The researchers wanted to see what kind of advice the advisors would give. Over a five‐month period, the actors made nearly 300 visits to financial advisors in the Boston area.

When shown a portfolio of index funds, most turned up their noses. Eighty‐five percent said actively managed funds were better.48

Richard A. Ferri and Alex C. Benke did a study for their white paper, A Case for Index Fund Portfolios. Between 1997 and 2012, they found that portfolios made up of one actively managed fund per asset class stood an 82.9 percent chance of losing to a portfolio of index funds. Portfolios with three actively managed funds per asset class had a 91 percent chance of underperforming.49 This study was done using funds available to Americans. Investors in other countries pay higher fees. This means their odds of beating index funds are significantly worse.

Most advisors have seen similar studies. Are they bad people for choosing less effective products—and lying about those products? Perhaps not. Studies show that money can make a good person, well…less good.

In 2006, Kathleen D. Vohs published a study called “The Psychological Consequences of Money.”50 It showed that money makes us selfish. Subjects played the board game Monopoly with an experimenter who posed as a subject. When the game was over, they put the board away. In some cases, a large stack of Monopoly money was left on the table. In other cases, a small stack or no money remained.

At this point, somebody walked into the room and dropped a box of pencils. It was a staged experiment to see if the subjects would help to pick them up. The subjects with a large sum of Monopoly money on the table picked up the fewest number of pencils.

During another test, an experimenter pretended to have a tough time with a problem. Those whose minds were imprinted by money beforehand weren't very helpful. It was the opposite for those who weren't primed by money.

According to Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, “The psychologist who has done this research, Kathleen Vohs, has been laudably restrained in discussing the implications of her findings.”51

What might she say about financial advisors with real money sitting on their tables? Her insight might explain why many of them lie.

That said, financial salespeople might choose actively managed funds and expensive offshore platforms for a couple of other reasons. They might be foolish or psychopathic. I'll explain that next.