Chapter 10

The 30 Questions Do‐It‐Yourself Investors Ask

What's the Difference between an Exchange‐Traded Index Fund (ETF) and an Index Fund?

An ETF and an index fund (also known as a tracker fund or indexed mutual fund) are much the same. If they track the same market and charge equivalent expense ratios, they should perform identically. For example, Vanguard's S&P 500 index fund holds the same 500 stocks that the iShares S&P 500 ETF holds. But the manner of purchasing an index fund and ETF differ. You buy index funds directly from a fund company. Doing so rarely incurs commission costs, and investors can often reinvest dividends for free.

In contrast, investors purchase ETFs directly from a stock exchange through a brokerage that usually charges commissions. As with regular index funds, investors also receive dividends. But there's rarely an option to reinvest those dividends automatically into additional ETF shares (iShares UK has some exceptions). Instead, dividend deposits—which come either monthly or quarterly—get lumped into the cash portion of the brokerage account. When you add new money to your account (from your savings) it also gets deposited into the cash portion of the account. You can use such cash to purchase an ETF holding, combining the money you deposited from your savings with any dividend cash in the account.

Nonexpatriate investors in some countries can purchase commission‐free index funds from a few select brokerages. But opportunities for expats to do likewise are limited. It's tempting for Canadian, Australian, or British expats to purchase index funds from their home‐country financial institutions. But doing so may generate higher taxable consequences.

Many expatriates (with Americans being an exception) can avoid paying capital gains taxes on investment profits if they invest with firms situated where they won't be charged capital gains taxes and if their resident country won't tax them on foreign earned investment gains. Legal tax havens for investments include locations such as Luxembourg, Singapore, Hong Kong, some of the British Isles, and the Cayman Islands.

Do Non‐Americans Have to Pay US Estate Taxes upon Death if They Own US Index Shares?

The US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is crafty. Non‐Americans buying ETFs off a US stock market could end up paying estate taxes to the US government at death if the investment holdings exceed US $60,000.1 Some people living la vida loca might enjoy sticking their heirs with an American estate tax, but most expats would prefer to bequeath money to their family, not the US government.

Table 10.1 shows four identical US index funds that non‐Americans could buy shares in through an offshore brokerage. The only differences are the expense ratio costs and where each product is domiciled. (Incidentally, all of these funds now post lower expense ratios than they did in 2013, when I researched for this book's first edition.)

Table 10.1 S&P 500 Indexes Available on Different Global Exchanges

SOURCES: Vanguard USA; Vanguard Canada; Vanguard UK; iShares Australia.

| ETF | Purchasing Symbol/Quote/Ticker and Available Exchange | Expense Ratio | Would US Estate Taxes Apply? |

| State Street Global Advisors S&P 500 ETF | SPY: New York Stock Exchange | 0.09% | Yes |

| Vanguard Canada S&P 500 ETF | VFV: Toronto Stock Exchange | 0.08% | No |

| Vanguard S&P 500 UCITS ETF | VUSA: London Stock Exchange | 0.07% | No |

| iShares Australia S&P 500 ETF | IVV: Australian Stock Exchange | 0.04% | No |

Costs as of June 2017.

What's a Sector‐Specific ETF?

Hundreds of different ETF products exist, many of which are sector specific. That means you can buy ETFs tracking almost anything: small company stocks, mining stocks, health care stocks, retail company stocks. Some of the ETFs flooding the markets are just plain wacky. An ETF focusing on the fishing industry is one.

Most exist to excite gamblers. Those thinking that mining stocks will surge this month may purchase a mining stock ETF, perhaps trading their health care ETFs to do so. Meanwhile, an even more backward stock market junkie might choose (and yes, it exists) an ETF specifically designed for its gut‐wrenching volatility. The ETF market is a bit like Bangkok. Anything goes.

Some investors (usually those who don't know what they're doing) buy sector‐based ETFs with the best recent performance record. For example, as I write this in June 2017, the iShares Nasdaq Biotechnology ETF reports a 10‐year compound annual return of 14.71 percent per year. The iShares US Medical Devices ETF has a 10‐year compound return of 11.64 percent per year.2 Both outperformed the US stock market index. But chasing yesterday's winners is an expensive game to play. Often, a hot‐performing sector during one time period often stinks like a turd over the next measured time period.

Such an overflow of different ETFs also pleases brokerages, allowing them to charge fees on every intoxicating trade.

Stick to ETFs providing broad international exposure and broad exposure to your home‐country market. The chapters that follow will show how to build responsible, diversified portfolios.

Should I Buy an Index that's Currency Hedged?

Not if you can help it. Some funds are hedged to a specific currency. When British investors buy, for example, a US stock market index, the fund is subjected to US dollar movements. When a fund company creates a currency‐hedged version, it attempts to limit the foreign currency's influence on the fund.

But currency fluctuations are natural. If we accept that, we'll be better off than if we try engineering fixes for the problem.

To understand the problems with currency‐hedged funds, it's important to recognize that currency fluctuations aren't always bad. If, for example, the British pound falls against most foreign currencies, then investors could profit from a nonhedged international index, as the growing strength of foreign currencies against the pound juices the returns of a foreign stock index in British pounds.

Buying products that try to smooth these ups and downs through currency hedging involves an extra layer of costs—and those costs can hurt your returns.

In Dan Bortolotti's book MoneySense Guide to the Perfect Portfolio, he outlines the true cost of hedging using two US S&P 500 indexes trading on the Canadian market. One was hedged to the Canadian dollar; the other was not. In theory, their returns in local currencies should be the same, but they're not even close. The currency hedging adds an extra cost of 1 percent to 3.5 percent per year.3

According to Raymond Kerzérho, a director of research at PWL Capital, currency‐hedged funds get burdened with high internal costs, dragging down results. In a PWL Capital research paper, he examined the returns of hedged S&P 500 indexes between 2006 and 2009. Even though the funds were meant to track the index, they underperformed it by an average of 1.49 percentage points per year. Although less dramatic, he also estimated that between 1980 and 2005, when currencies were less volatile, the tracking errors caused by hedging would have cost 0.23 percentage points per year.4

The more cross‐currency transactions that a fund makes, the higher its expenses—because even financial institutions pay fees to have money moved around. Consider the example of a currency exchange booth at an airport. Take a $10 Canadian bill and convert it into euros. Then take the euros they give you, and ask for $10 Canadian back. You'll get turned down. The spreads you pay between the buy and sell rates will ensure that you come away with less than $10.

Large institutions don't pay such high spreads, but they still pay spreads.

With indexes, it's best to go with a naturally unhedged product. Accepting currency volatility (instead of trying to hedge against it) will increase your odds of higher returns.

If an ETF is currency‐hedged, it will say so. For example, here are two S&P 500 ETFs that trade on the Canadian stock market. Here's how they look on the iShares Canada website:

XSP iShares S&P 500 Index ETF (CAD‐Hedged)

XUS iShares Core S&P 500 Index ETF

They each track the same stocks. But the first one (XSP) is hedged to the Canadian dollar.

If bond ETFs are currency‐hedged, they don't tend to have the same long‐term performance drags that occur with currency‐hedged stock market ETFs, when compared to their non‐hedged alternatives.

What's the Scoop on Withholding Taxes? (For Non‐Americans)

Most stocks pay dividends, which are cash proceeds to shareholders. Indexes and exchange‐traded funds do likewise because they comprise individual stocks. Regardless of whether your money is situated in a capital‐gains‐free zone, most investors are liable for dividend taxes.

I'll show a Canadian stock market ETF to demonstrate how much an investor would pay in dividend withholding taxes.

If you averaged a pretax return of 10 percent per year, roughly 8 percent of that growth would come from capital appreciation. Such growth reflects the rising value of the stocks within the index. Most stocks pay shareholder dividends as well, and ETF investors are entitled to their share. If dividends were 2 percent per year, then you would pay 15 percent tax on your 2 percent dividend. In this case, your 2 percent dividend would be reduced to 1.7 percent. As a result, if the pretax return on your ETF were 10 percent, your posttax return would be 9.7 percent.

How Withholding Taxes Affect Returns on a Canadian ETF or Stock

- 8% from capital gains

- +2% from dividends

- 10% pretax return

- 15% tax on dividends (2 × 0.15 = 0.3)

- =10% pretax return – 0.3% dividend tax

- Net return: 9.7%

Non‐American expats choosing to own individual US stocks (Google, Microsoft, Coca‐Cola, etc.) must fill out a W‐8BEN form. It's officially known as a “Certificate of Foreign Status of Beneficial Owner for United States Tax Withholding.” Brokerages mail the forms to investors every couple of years. Investors fill them out before mailing them back to the brokerages. The brokerage then sends them to the IRS.

ETF investors trading on non‐US stock exchanges don't have to fill out such forms. But there's one thing to remember. In most cases, they're still charged withholding taxes. The rate may differ, depending on the country's respective tax treaty, but if there are US stocks within the index (for example), the US government has a way of siphoning off money. You probably won't see it, so consider it a ghost tax.

Investors in offshore pension schemes also pay dividend withholding taxes. Unknowledgeable sales reps won't disclose this, but the company must. Here's an example on the Friends Provident International website, under “Investment Benefits”:

Virtually tax free accumulation of your savings (some dividends may be received net of withholding tax, deducted at source in the country of origin)….5

And once again, on the Royal Skandia [Old Mutual] offshore pension website:

…certain investment income accruing to a fund may be subject to a tax deduction at source which is withheld in the country where the investment is situated.6

When investing offshore using ETFs, you can see the tax machinery under the hood. Other costs of the financial industry also become apparent. Many can't be avoided, but it's good to know what they are.

Will You Have to Pay Currency Conversions?

If an investor earning a salary in Malaysian ringgit buys a mutual fund of Southeast Asian stocks, she'll get dinged on a currency conversion. Investors earning Australian dollars and buying a global stock market mutual fund will pay likewise. There's no way around this. You might not see the cost of such a transaction, but that doesn't mean it doesn't exist.

For instance, if your salary is in Indian rupees and you buy an Indian stock or shares in an Indian stock market mutual fund, you won't pay a currency conversion fee. However, if the same Indian‐based investor bought an Indian‐based mutual fund focusing on US stocks, some kind of currency spread would take a nibble from the fund's returns. The Indian fund manager would need to convert Indian rupees to purchase the fund's US stocks.

You'll never see such costs on your statement, of course, but they're an unavoidable cost of doing business.

When investing in ETFs from a brokerage, you'll likely see such nibbling fees. It's much like driving a car with a transparent hood. If your salary is in Singapore dollars and you buy a global ETF off the Canadian stock market, your money will be converted to Canadian dollars. Like a money exchange at an international airport, the banks are going to take a bite. Don't let anyone convince you otherwise.

Such hidden banking costs occur only during transactions. And they're negligible, compared to high ongoing mutual fund costs or account fees.

Should I Be Concerned about Currency Risks?

Many investors think that if they buy an ETF priced in a foreign currency, their money is subject to that foreign currency's movement. This isn't the case. For example, assume a Spanish expatriate buys an ETF tracking the Spanish market. If he buys it off a British stock exchange, the investor will see the price quoted in British pounds. However, the movement of the English currency has no bearing on the Spanish ETF.

Imagine the following scenario:

- An investor buys a Spanish ETF trading at 20 pounds per unit on the British market.

- Spanish stocks slide sideways for one year after the investor purchases the ETF.

- The British pound falls 50 percent against the euro during that year.

The British pound's movement wouldn't affect the investment itself. In this case, despite the fact that the Spanish market didn't make money, the ETF purchased at 20 pounds per unit would now be priced at 40 pounds per unit. The British currency crash would affect the ETF's listed price in pounds, but its overall value in euros would be entirely dependent on the movement of the Spanish stock market.

Likewise, a New Zealander buying a global stock market ETF off the Australian market wouldn't be pegged to the value of the Aussie dollar. While the ETF may be priced in Australian dollars, its holdings reflect the currencies of the stock markets it tracks. If the Australian dollar dropped 90 percent compared to a basket of global currencies, a global stock market index trading on the Aussie market would shoot skyward in price. Australian dollar currency movements wouldn't affect its true value.

New investors sometimes compare posted performance returns in different currencies. They might ask, “Why is the posted five‐year return on the global stock market index in US dollars different to the posted five‐year return on the global stock market in GBP?” The returns are actually identical if the gains are converted into a constant currency.

Do the Unit Prices of ETFs Show Which are Expensive or Cheap?

I often receive e‐mails from investors asking me about the prices associated with certain exchange‐traded funds. For instance, an American might see a Vanguard S&P 500 ETF trading at $90 per share, and an iShares S&P 500 ETF trading at $180 per share. Although Vanguard and iShares are different providers, their respective ETFs are still tracking the same 500 large American stocks. Their values are identical.

In the same vein, five $1 bills aren't worth less than one $5 bill. The quoted price difference between two ETFs tracking the same market is a mirage.

That said, one ETF is actually cheaper than another if its expense ratio is lower. If Vanguard's S&P 500 ETF has an expense ratio of 0.09 percent per year and the iShares S&P 500 ETF carries costs of just 0.07 percent, the iShares ETF would be cheaper, based on its lower annual fee.

If I Have a Lump Sum, Should I Invest It All at Once?

Most stock market investors add monthly or quarterly to their investments. Such a process is called dollar cost averaging. Doing so ensures that they pay less than an average cost over time. If they invest a constant, standard sum, they'll purchase more units when prices are low and fewer units when prices are high.

But what if you found $100,000 on the street? You report it to the local police, nobody claims it, and you become the happy (or paranoid) recipient of a drug dealer's spoils. Should you invest it all at once, or divide your purchases over many months or quarters?

Much depends on your psychology. If you invest the entire amount and the markets crash 20 percent the following day, how would you feel? If it wouldn't bother you, consider the lump‐sum investment. This is based on findings by University of Connecticut finance professors John R. Knight and Lewis Mandell. In a 1993 study spanning a variety of time periods, they found that investing a windfall up front beat dollar cost averaging most of the time.7

Vanguard agrees. They published a similar study in 2012. It came to the same conclusion.8

Odds will be in your favor if you invest the money as soon as you have it.

I'm in Some Expensive Products, but They're Currently Down in Value. Should I Sell Now or Wait?

Selling investments at a loss is like a kick to the groin. But if your money is languishing in a high‐cost account, making a switch is usually best. Don't wait until the account recovers. Here's why:

Rising and falling markets influence most investment portfolios. If a well‐allocated, actively managed portfolio gets hammered in a given year, a well‐allocated index portfolio would have done likewise. The opposite applies during years when the markets roar: a rising tide raises all boats. This is one of the reasons you can't congratulate yourself (or your advisor) for gaining 15 percent, 20 percent, even 25 percent in a single year. The big question should be: How did an equally allocated portfolio of index funds perform in comparison?

Here's another example that puts the same concept in perspective.

Imagine you bought a house for $100,000. It drops in value to $80,000. You're interested in buying the house next door, but you would need to sell your own house in order to do so. Should you wait for your house to rise in value, back to the $100,000 you paid, before buying the house next door? If you do, you're nuts. The same factors increasing the price of your home would do likewise for the house next door.

The same premise applies with the stock and bond markets. If you're trading one diversified portfolio for another, you'll make a market‐to‐market switch. If stock markets are on a low and you sell your high‐cost account to build an index portfolio, you'll likely be selling and buying on a low as well. If markets are on a high, you'll be selling high to buy high. Whatever you do, don't time your sales or purchases based on where you or someone else thinks the markets are headed. That's a fool's mistake.

How Do I Open a Brokerage Account and Make Purchases? (For Non‐Americans)

You might discover that your local offshore bank offers a low‐cost brokerage, and that you could open such an account to purchase ETFs. But be careful. Don't wander down to the bank without a clear mission. Banks exist to make money. If you aren't forceful, they might rob you: trading currencies on your behalf, bleeding you with an offshore pension, or cajoling you into their favorite actively managed unit trust.

You're looking for gems in an ogre's den. Be clear about what you want. Don't let anyone sway you.

Tell the financial institution you want to open a brokerage account providing access to a variety of different markets. No, you don't want their advice. No, you don't want their super‐duper market research. No, you don't want a free trip to expense‐ville.

Ask to open a no‐frills, low‐cost brokerage trading account.

Here are the steps to follow:

- Know what you want to buy.

Each ETF has a ticker symbol or quote that you can locate either from the website of the ETF provider or with a Google search. If, for example, you want a Canadian stock index trading on the Toronto market, you could find such a symbol at Vanguard Canada or iShares Canada.

Vanguard offers its FTSE Canada All Cap Index constituting 245 Canadian stocks of various sizes. It charges a paltry 0.12 percent a year. A quick search on the iShares site shows that the iShares S&P/TSX Capped Composite index ETF comprises roughly the same number of stocks, but its expense ratio is a barrel‐scraping 0.05 percent per year. Which would you buy? Considering that both track the same market and the same number of stocks, it pays to go with the iShares product because it's cheaper. Its trading ticker symbol is XIC.

If you were purchasing off the British or Australian stock exchanges, you would do much the same thing. Determine what you want, then do a comparative search using at least two large providers. Vanguard UK and iShares UK work well for Brits and Europeans. Vanguard Australia and iShares Australia suit Aussies. Asians or South American expats could take their pick from ETF providers based in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, or Hong Kong.

- Determine how many units you want.

You'll know how much money you want to invest, but you'll need to find out how many units of the ETF this will buy. With some online brokerages, you'll be able to find your desired product's unit price. If it's unavailable on the brokerage site, you could use a variety of online searches instead. Let's assume you want to invest $10,000. If you wanted the iShares Canadian index (XIC), you could use Yahoo! Finance or Morningstar to look up its current price.

Assume that the price per unit were C$23.87. In such a case, if you have C$10,000 to invest, you could afford to buy 418 units ($10,000 divided by $23.87 per share = 418.94). You'll only be able to purchase whole shares, and, while $10,000 would buy 418 units at $23.87, market prices could change slightly before the transaction is completed. There's also a purchase commission to consider. For these reasons, order a conservative number, like 400 units.

If you're getting paid in a currency other than Canadian dollars, remember to convert the currency to the denomination of the ETF. You won't have enough money, for instance, if you try buying 400 units of this ETF with $10,000 Hong Kong dollars. The Canadian dollar (which the ETF is denominated in) is worth much more.

- Make your purchase.

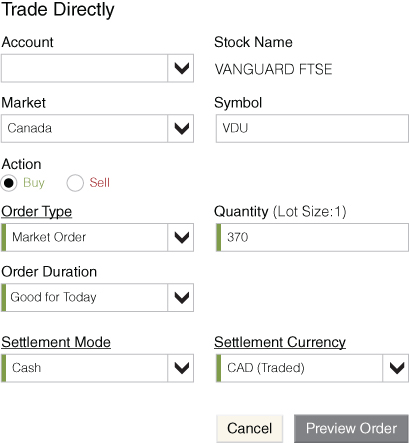

Regardless of the brokerage selected, steps to purchasing an ETF are similar. When you can do it with one brokerage, you can do it with almost any. I'll use examples from three separate brokerages.

When your account is set up and the cash is ready to go, simply log in. Select “trade” or “order entry” to make the purchase. Figure 10.1 shows how it looks with DBS Vickers when purchasing 370 shares of Vanguard's international developed world index.

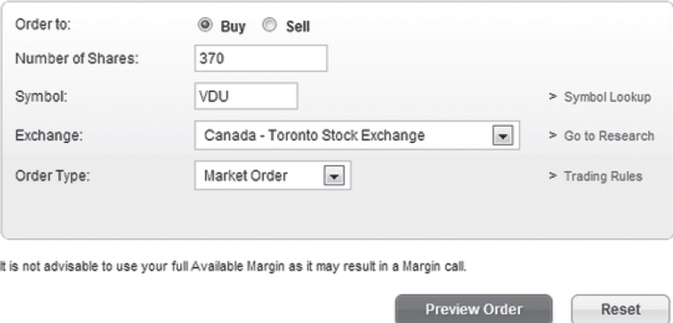

The same purchase is just as simple using TD International's [Internaxx's] brokerage in Luxembourg. Figure 10.2 is a screen shot of the same order.

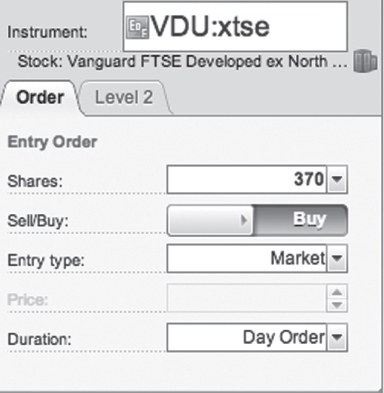

And Figure 10.3 shows what the purchase screen looks like using Saxo Capital Markets. Note that this brokerage refers to the ticker symbol as the “instrument.”

Because the investors in these examples would be purchasing off the Canadian exchange, they would select “Canada” for the market/exchange.

They would select the order to “buy,” then enter the number of shares they can purchase, before choosing the ETF symbol (VDU in this case). For order type there's usually an option to select “market” or “limit.”

When selecting a market order, you're agreeing to pay the current price or (if the stock market is closed) the price at which the ETF trades when the markets reopen. During stock market trading hours, prices fluctuate. By choosing a market order, you may end up paying a slightly higher or lower price than the latest quote. The stock market doesn't have to be open when you make a purchase order. For example, Australians purchasing an Aussie stock index through TD International can do so even if the Australian markets are closed. The order would be processed once the markets reopened.

Instead of choosing market orders, some people prefer the limit order option. In this case, you could enter a price that represents the maximum you would pay for the day. If the price of the ETF drops to that price, the transaction goes through. If you enter a limit order at $26.28 per share (because that was the last quoted price of the trading session) and the ETF opens trading at $25 the following day, you'll pay $25 for the purchase, not $26.28.

If it doesn't drop to the price you select, the order won't go through. As with market orders, you can also place limit orders when the markets are closed.

Some brokerages don't allow for market orders, insisting you place limit orders instead. PWL Capital's Dan Bortolotti says this is a good thing. He places numerous limit orders on behalf of his clients every day. He says investors shouldn't place orders when the market isn't open. When buying, he says investors should place limit orders for ETFs at the current market price, or a few cents above it. When selling, he says its best to set a limit price at the current market price or a few cents below it. Sometimes, ETFs get mispriced. This means investors who place market orders could be in for a surprise if an ETF's price goes a little haywire during trading hours. They could end up paying an unusual, inflated price.

Figure 10.1 Purchasing 370 Shares of Vanguard's International Developed World Index

SOURCE: DBS Vickers.

Figure 10.2 Purchase Using TD International's Brokerage in Luxembourg

SOURCE: TD Direct Investing International.

Figure 10.3 Purchase Using Saxo Capital Markets

SOURCE: Saxo Capital Markets.

What If I Find a Higher‐Performing Bond Index?

Some people might find better‐performing bond indexes than what they originally start with. But always remember that the past is rarely repeated in the future. If a bond ETF pays a 4 percent yield today and a different bond ETF pays 2 percent, don't consider the yields to be carved in stone. Prices of the bonds themselves, as well as the ever‐changing average yields (while new bonds replace old) can influence bond ETF returns. Rather than obsessing over past returns and current interest yields, here are the three most important considerations:

- Ensure that your bond ETF comprises just first‐world government or AAA‐rated corporate bonds.

- When possible, make sure it comprises short‐term bonds (maturing in three or fewer years) or buy a broad bond market index (never a long‐term bond index).

- Ensure that the expense ratio charge is 0.4 percent or less.

What If I Find a Cheaper ETF?

New ETFs keep getting launched. Be wary of trading. Moving from one ETF to another will cost a commission fee, and it might not be worth it. An ETF charging 0.15 percent per year costs just $15 for every $10,000 invested. Another ETF charging 0.12 percent would cost $12. Is it really worth saving $3 per year when it might cost as much as $50 to make a trade?

Brokerages want you to trade. But don't. Rapid trading equals more money for the brokerage, less for the trader. Many brokerages offer discounted commissions to frequent traders. But don't get sucked into the bank's web.

Should I Be Most Concerned about Commissions, Annual Account Fees, Fund Costs, or Exchange Rate Fees?

Hands down, ongoing fund costs and annual account fees are far more detrimental than commissions and exchange rate fees. Here are two scenarios. Joe pays 3 percent commissions on each of his purchases. Joe then pays 0.3 percent in hidden ETF expense ratio charges, with no additional account fees.

Julie doesn't pay any commissions to purchase her investments, but her mutual fund expense ratios average 1.5 percent per year, and her account carries an additional 1 percent annual cost. As you'll see, annual costs on the account's total value are a far bigger drag on profits than commissions are.

If Joe and Julie each invested $10,000 per year, earning 8 percent per year before fees, Table 10.2 shows how their profits would compare.

Table 10.2 Joe's and Julie's Profits

| Joe | Julie | |

| Invests per year | $10,000 | $10,000 |

| Commission paid on purchases | 3% | 0% |

| Amount annually invested after commissions | $9,700 | $10,000 |

| Annual return made before fees | 8% | 8% |

| Annual fund/account costs | 0.3% | 2.5% |

| Annual returns after fees | 7.7% | 5.5% |

| Investment duration | 25 years | 25 years |

| Money grows to | $731,066.88 | $539,659.81 |

Sure, purchase commissions and exchange rate costs are a pain. I liken them to doing a bike race, where once in a while your opponent leans over and flicks at your brake. But ongoing account fees and high fund charges are worse. They're like another rider holding your seat for the duration of the race.

How Little Can I Invest Each Month?

Some brokerages, such as Vanguard for Americans, allow people to invest as little as $100 a month. But those using a discount brokerage (and paying commissions on each purchase) should consider only larger monthly sums.

Let's assume you're a non‐American using a brokerage where minimum commissions are 28 euros per trade. If you invest 100 euros, you would be giving away 28 percent in commissions. To keep costs low, think of the 1 percent rule. Never pay more than 1 percent of your total invested proceeds in commissions.

You can't exactly strong‐arm your brokerage into providing a better deal. But think strategically about how much you'll invest at any one time. Assume minimum commissions are 28 euros. By following the 1 percent rule, you would never invest less than 2,800 euros. If you don't have 2,800 euros a month, save for the investing occasion.

Perhaps you can save 500 euros monthly. In this case, keep the money in a savings account until you've accumulated 2,800 euros. Then make your purchase.

Don't be afraid to buy one index at a time. The first time you save 2,800 euros, perhaps you could buy an international stock index. A few months later, buy a bond index. Build your portfolio slowly, one index at a time. Don't worry about rebalancing until your portfolio hits roughly 50,000 euros. From that point, just make purchases that will align your portfolio with its goal allocation.

Stock Markets Are High. Should I Really Start Investing?

Finance writers and news media love writing headlines such as these: “US Markets Hit Their Highest Point Ever!” “Are Stocks Ready for a Crash?” “Bonds Are Ready to Fall!”

Let me cut through the murk and give you the market certainties. Ready?

- Stocks will continue to hit new heights.

- Stocks will crash.

- Bonds will decline in value.

- Bonds will rise in value.

These four scenarios will occur over and over during your investment lifetime. Those trying to time their purchases and sales will almost certainly underperform a disciplined, rebalanced portfolio of stock and bond indexes. Sure, you might make a lucky prediction once or twice. But that would be a travesty. Much like the guy who wins big during his first trip to the casino, he's going to go back. And eventually the house will win.

When building your investment portfolio, forget about predictions. If you're adding a lump sum (because you happen to have the money), diversify it properly. Don't try to guess whether you should buy bonds, buy stocks, or sit on your rump waiting for a better deal. Investing isn't a sprint; it's an ultramarathon. You're not trying to race somebody else to the next telephone pole. The real finish line is many years ahead.

Always remember how the average investor performs. Fear, greed, and general speculation cause investors to buy high, sell low, and miss opportunities. Instead, put your calculating brain toward something more constructive: how to best wash the car, shave your face or legs, or get a whole pizza down your gullet in less than five minutes. Speculating with the stock market is a loser's game. If you can't restrain yourself, hire an advisor.

Should I Buy ETFs from Vanguard, iShares, Schwab or Another Low‐Cost Provider?

This is a bit like asking, “Should I buy my bananas from WalMart or Safeway?” If two ETFs track the same market, you're buying the same bananas. Fund companies post expense ratios on their websites. It matters little, for example, whether you choose Vanguard, iShares, or Schwab. These are three of the biggest names in the world of ETFs. As such, they're good at tracking stock market returns and their costs are competitive. If all other things are equal, choose the ETF with the lowest expense ratio.

Can Muslims Build a Portfolio of Shariah‐Compliant Funds?

Muslims want to respect Shariah law. That's why they shouldn't invest in companies that sell or produce alcohol, tobacco, pork products, conventional financial services (banking, insurance, etc.), weapons, defense products, and entertainment.

Shariah compliance also means Muslims should shun government and corporate bonds. The Koran states that interest payments are considered usury. This makes it tougher to create a diversified portfolio.

But it's not impossible.

As shown in Table 10.3, the London Stock Exchange now offers four Shariah‐compliant index funds (ETFs).

Table 10.3 Shariah‐Compliant ETFs on the London Stock Exchange

| ETF | Expense Ratio | Invests In… |

| iShares MSCI World Islamic ETF (ISWD) | 0.60% | European, US, Asian‐Pacific, and emerging‐market stocks |

| db X‐trackers DJ Islamic Market Titans 100 UCITS ETF (XMIT) | 0.50% | European, US, and Asian‐Pacific stocks |

| iShares MSCI USA Islamic ETF (ISUS) | 0.50% | US stocks |

| iShares MSCI Emerging Markets Islamic ETF (ISEM) | 0.85% | Emerging‐market stocks |

Over the five‐year period ending March 31, 2017, the iShares World Islamic ETF (ISWD) averaged a compound annual return of 9.56 percent. By comparison, the iShares Core MSCI World Index (SWDA) gained an average of 12.46 percent. This second index (SWDA) isn't Shariah compliant.9

But don't assume Shariah‐compliant index funds won't perform as well. Sometimes, they'll beat plain vanilla index funds. Other times, they won't. For example, during the 2008–2009 financial crisis, Shariah‐compliant funds trounced the returns of traditional index funds because the stocks of financial companies led that decline. Shariah‐compliant funds didn't own such stocks.

Over an investment lifetime, a global Shariah‐compliant index should perform much like a traditional global index fund.

Mohammad Hassan is a senior analyst with Singapore‐based Eurekahedge, the world's largest independent hedge fund data provider. It's also an alternative research firm that covers the global Islamic funds industry.

“Since 2007, worldwide assets under management for Islamic funds have doubled,” says Hassan. “There are now 877 funds worldwide, with around $90 billion in assets under management.”

Still, he isn't impressed by the industry's growth. “The public, even Muslims in Islamic finance hubs, are generally unfamiliar about investing with Islamic funds,” he says. “Most opt to leave their money inside their bank accounts.”10

Unfortunately, when Muslims stockpile money in a savings account, it benefits the banks. Banks use that money, often loaning it and charging interest to people. That's why it's better (and much more profitable) for Muslims to invest their money in Shariah‐compliant index funds.

Could You Build a Portfolio of Socially Responsible Index Funds?

I once met an expat who refused to invest. He didn't want to support businesses that supported building missiles, hooking kids on cigarettes, or extracting air‐polluting fossil fuels. He met a financial salesperson who offered a solution. “Buy this socially responsible fund,” he said. But its fees were higher than a looped‐out guy at a Burning Man event.

Fortunately, socially responsible (SRI) index funds exist.

Most SRI funds don't invest in industries that manufacture tobacco, alcoholic beverages, weapons, or nuclear power. But SRI investors face a few challenges. They might not find a fund that aligns with their beliefs. For example, Charles H. Hennekens and Felicita Andreotti reported in the American Journal of Medicine that obesity may soon overcome smoking as the leading cause of preventative death in the United States. Unfortunately, SRI funds don't discriminate against manufacturers of fast food, soft drinks, and processed foods.11

Still, SRI index funds have screened out many of Mother Earth's foes. As with Shariah‐compliant funds, sometimes they'll beat traditional index funds. Sometimes they won't. But over long periods of time, they should provide similar returns to traditional index funds. Many people believe that SRI funds don't perform as well. But that isn't true.

A research paper by RBC Global Asset Management proves it. The FTSE KLD 400 Index tracks the performance of socially responsible US stocks. From April 1990 to April 2012, it beat the S&P 500.12

In the chapters ahead, I've provided sample portfolios with SRI funds.

Why Doesn't My Brokerage Offer the Funds I Want?

Plenty of brokerages list a series of funds or available ETFs. Investors often mistake these lists for their respective brokerage's entire universe of offerings. But it isn't. When a brokerage offers access to the Toronto Stock Exchange, for example, investors have access to every stock or ETF that trades on that exchange. Don't get confused by a brokerage's list of selected funds. They simply can't list everything—so they don't. But if the brokerage provides access to a given market exchange, investors can buy anything that trades on that exchange.

For example, more than 6,000 stocks trade on US stock exchanges. Almost 1,600 trade on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The London Stock Exchange lists about 2,500 companies from around Europe. No brokerage would be crazy enough to list all these companies on a convenient home page.

The same goes for all the ETFs that trade on each respective market. If you try to order an ETF that you see in this book, and the brokerage declines the order, get on the phone and call them. They'll make sure you can buy it. They can't afford not to.

Why Hasn't My Bond ETF Risen in Value?

Bond index funds rise and fall in price. But over the long term, they aren't meant to gain elevation. Long term, profits are derived from bond interest payments. Some investors think they've lost money on their bond index, if the unit price has dropped. But with short‐term or broad bond market index funds (or ETFs), that rarely happens over a period of two or more years. If it does occur, it will eventually revert to the mean. For example, we could look at the iShares Core Canadian Short‐Term Bond Market Index.

As of this writing (July 2017), it traded at $28.06 per share. Investors who own this index might think it lost money over the previous three years if they're simply looking at the ETF's unit price on their brokerage statement. After all, on July 1, 2013, it was priced at $28.58.

But this bond index made a profit. It paid regular interest. This went into the cash portion of the brokerage account. If you look at the website at iShares.ca, you'll see this bond ETF's performance, including all interest. According to iShares, this bond index gained a compound annual return of 1.82 percent per year over the three‐year period ending June 2017. That's a total three‐year gain of 5.56 percent. No, it isn't great. But despite what many investors think, it didn't lose money.

From now until 2055 (I made up that year) this ETF's price will float slightly above and slightly below $28.06. Investors don't gain or lose money (at least, not long‐term) based on gains from bond ETF unit prices. They just float up and down while the bonds within the ETF keep dishing out interest.

What If My Bond ETF Is Priced in a Different Currency?

Some investors own international bond ETFs that are priced in US dollars. If the US dollar rises against other currencies, the price of such a bond ETF will show an exaggerated loss. For an American investor, that loss could be real. After all, if they plan to retire in the United States, they'll pay future bills in US dollars. As such, if they buy an international bond market index, they would be taking a currency risk.

But for a non‐American investor, that loss isn't real. Always remember that the listed currency of an ETF is irrelevant. For example, if a French investor buys a European bond ETF listed in US dollars, he isn't making a US dollar investment. Instead, he's buying bonds that are valued in euros.

If the US dollar rises against the euro, his bond ETF's price will fall. But if he sold the bonds (seemingly at a loss) and converted the proceeds into euros, he'll likely find that he didn't lose money if he measures his success in euros … including interest.

Are Cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, Good Investments?

These are the four most dangerous words for any investor:

This. Time. It's. Different.

If you're reading this after Bitcoin or another cryptocurrency has made a big gain, you'll think, “Hell yeah, these are great investments!” If, on the other hand, cryptocurrencies have recently taken a dump, you're likely thinking, “These things are horrible. They're not real investments.”

As I write this, Bitcoin is kicking sand in the face of traditional investments. Between July 1, 2013, and June 13, 2017, it gained 3,130 percent.13 To put that in perspective, it took Vanguard's S&P 500 thirty years (from its 1976 inception) to make investors that much money.

Bitcoin's price rose more than 170 percent during the first six months of 2017. If you had bought Bitcoin's rival, Ethereum, you might be even giddier. During the six‐month period ending June 13, 2017, it gained more than 3,500 percent.14 Bitcoin was the first cryptocurrency. It's also the most widely accepted. Satoshi Nakamoto (who isn't a real guy) is the pseudonym of the person who created it in 2008. It's a peer‐to‐peer electronic cash system.

Drug dealers were among the first to use Bitcoin. That's because it's tough for authorities to track digital currencies. Since its introduction, however, Bitcoin has yoyoed like a junkie on speed. If you had invested $1,000 in Bitcoin in November 2013, it would have been worth just $150 two months later.

This kind of drop could leave its users or investors with a really big headache. Business Insider UK interviewed a drug dealer in 2015. He was burned by Bitcoin's then‐recent crash. “It's pretty damn sad,” he said. “We have worked so hard over the past 3 months, and for profits to get halved? It's hard to swallow, simple as that, but what can you do. It's a gamble, whether you hold or sell.”15

I don't feel sorry for a guy who pushes drugs. But there's truth to what he says. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies aren't businesses, bonds, or real estate. They don't create cash. They rely, instead, on the greater fool theory. They're only worth as much as the market wants to pay.

Short term, that's also the case with stocks. But if they produce cash—from reinvested earnings or dividends—their prices can keep rising. If they don't create profits, their prices won't increase. Assume a pharmaceutical company finds a cure for cancer. Its stock would soar. But if business profits didn't follow, it would eventually crash back to Earth.

Each generation has to learn the same lesson. In the early 1700s, Sir Issac Newton fell for a company that promised to shake the business world. He bought South Sea Company stock. It was meant to facilitate trade with the Americas. Back then, that was like a promise to bring riches from the moon. The stock rose on hope. But it was a fast‐talking boxer who couldn't throw a punch. The business didn't earn profits, so the stock price soon collapsed. Newton lost a small fortune. In a way of mocking everyone involved (including himself), he said, “I can calculate the movement of stars, but not the madness of men.”16

“This time it's different.” These words were whispered during The South Sea Bubble. They were uttered during the 1600s Dutch Tulip Craze when multicolored tulips were as expensive as some houses. They were shouted from the rooftops during the 1990s dot‐com charade. Tech stocks had soared high on hot air, until sobriety (and the stocks' lack of business profits) brought them crashing back to Earth.

Bitcoin and its contemporaries don't make profits either. As a medium of exchange, they're like new‐age checks or fancy money orders. Much like a gold rush, those who make profits will be selling picks and shovels. One such firm is iPayYou.io. It charges shoppers who use Bitcoin to buy off Amazon.com. As Money's David Jacobson says, most mainstream companies don't directly accept cryptocurrencies.17

As for investing in Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies, it might be best to turn an ear to Warren Buffett.

In an interview with CNBC, he said, “Stay away. Bitcoin is a mirage. It's a method of transmitting money… . The idea that it has some huge intrinsic value is just a joke in my view.”18

Should I Buy a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) Index?

You're getting comfortable in bed. Then the phone rings. Your tenants have an emergency. A pipe broke in their bathroom and the place is starting to stink. Forget that early night. You have work to do.

Many people enjoy the business of renting out a home. Others don't. But if you own a home already (whether you're renting it out or not), you're a real estate investor. It might even comprise a large part of your net worth.

Some people, however, don't own real estate. They wish they could do it without the added hassle that might come with crazy tenants. Such investors might add a REIT to their portfolios.

REITs are real estate companies that buy income‐producing properties. Some focus on hospitals. Others focus on office buildings, shopping malls, or warehouses. They collect rents from tenants, as you would with a second home. But nobody bugs you—ever.

REITs trade on the stock market. You could buy a collection all at once with a REIT or ETF.

Dividend payouts tend to be higher than they are with common stocks. Historically, REITs and traditional stocks battle like Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. Sometimes REITs win. Other times, traditional stocks knock them out.

Between 1996 and 1999, US stocks pounded American REITs into a corner. Between 1999 and 2002, REITs reigned supreme. REITs then outclassed stocks for the next five years. But when the financial crisis arrived in 2008, both hit the canvas. It didn't take long, however, before they both recovered well.19

By adding real estate to a portfolio of stocks and bonds, investors might enhance returns while decreasing volatility. Using data from Standard & Poor's, Barclays, and Gerstein Fisher Research, Forbes contributor Gregg S. Fisher gave two historical portfolio scenarios. By investing 60 percent in US stocks and 40 percent in US bonds, he found a portfolio would have averaged a compounding return of 8.72 percent between January 1990 and October 2014.

If, however, investors had added a 10 percent overall allocation to global REITs, compounding returns would have improved to 8.83 percent per year. The portfolio, with REITs, would have also been less volatile.

Fisher also checked different rolling 10‐year periods. For example, how did they stack up between 1990 and 2000? How did they compare between 1991 and 2001? Did he find different results between 1992 and 2012? Fisher writes, “In about 80 percent of rolling 10‐year periods, the portfolio with [10 percent real estate added] … achieved a higher return; volatility was lower in about 65 percent of the same periods.”20

If you add a portion of REITs, remember one thing. Diversification is smart. Rebalance once a year. Don't abandon your REITs after they've had a bad run. And don't chase them with fresh money when they become the rocket in your account.

Should I Buy a Smart Beta ETF?

Marketers are smart. They know that plenty of investors like low‐cost index funds. But those who smell opportunity have sprinkled fairy dust. Many firms have created smart beta funds, also known as factor‐based funds.

Smart beta firms use back‐tests. They claim that index funds weighted differently produce better returns. For example, take a traditional index fund. Its stock weightings will emphasize the largest stocks. If Apple is the largest company in the S&P 500, then Apple's fortunes (good or bad) would have the greatest influence on the S&P 500. Smart beta indexes promise something different. Sometimes, they build higher emphasis on stocks that are quickly moving up in price.

Other times, they build equal weighted indexes. In this case, larger stocks don't move the index fund's needle any more than smaller stocks do.

Back‐tests often dazzle. They prove that such index fund strategies would have triumphed in the past. But the past isn't the future. Often, the newly emphasized stocks in these index funds become more expensive. This can hurt returns.

Research Affiliates' Rob Arnott, Noah Beck, Vitali Kalesnik, and John West say that smart beta or factor‐based funds could disappoint investors. They published the paper “How Can ‘Smart Beta’ Go Horribly Wrong?”21 In it, they show that much of the past decade's market‐beating gains from such funds have come from rising valuations. Investors rushed into such funds because they had performed well. That raised the price‐to‐earnings (PE) ratios of certain stocks to higher than normal levels.

Higher‐than‐normal valuation levels could bring poor returns in the future. Here are some factor‐based (smart beta) styles so you'll know them when you see them: Momentum, Value, Growth, Small‐Cap, Equal‐Weighted, Quality, and Minimum Volatility.

Smart beta index funds are cheap, compared to actively managed funds. But they cost a lot more than most standard index funds. Strategies based on a cherry‐picked past might sell new Wall Street products. But they aren't always better for investors. That's why I suggest that you keep things simple.

Should I Invest in Gold?

Here's a cool trick that you should try on the street.

Find some educated people. Ask them to imagine that one of their forefathers bought $1 worth of gold in 1801. Then ask what it would have been worth in 2017.

Their eyes might widen at the thought of the great things they could buy if they sold that gold. They might imagine buying a yacht or a personal jet. Unfortunately, they couldn't afford either. With the proceeds, they couldn't treat three friends to beer and burgers at a pub. One dollar invested in gold in 1801 was only worth about $52 by 2017.

How about $1 invested in the US stock market? Now you can start thinking about your yacht. One dollar invested in the US stock market in 1801 would have been worth about $17 million by 2017.22

Gold isn't an investment that can expect to beat inflation. From time to time, it jumps around a lot. But in a long‐term game, it comes up short. When I wrote this book's first edition, I included gold in something called the Permanent Portfolio. Rebalanced annually, such a portfolio has done well—but not because of gold's long‐term growth. If you're curious, and you haven't read my book's first edition, check out my online story, “The World's Best Investment Strategy That Nobody Seems to Like” at AssetBuilder.com.23

Don't Small‐Company Stocks Beat Larger‐Company Stocks?

Whenever possible, I recommend total stock market index funds instead of breaking down investment allocations into different sized indexes. For example, investors can buy large‐company indexes, medium‐sized company indexes, or small‐sized company indexes.

I prefer to keep things simple. It's true that, historically, there's evidence to suggest small‐company stocks beat large‐company stocks. But there's also evidence against that.

Economic Nobel Prize winner Eugene Fama and his colleague Kenneth French determined that between July 1926 and February 2012, small‐cap stocks cumulatively beat large stocks by 253 percent.24 But in 1999, Tyler Shumway and Vincent Warther argued otherwise. They published a paper in the Journal of Finance, “The Delisting Bias in CRSPs NASDAQ Data and Its Implications for the Size Effect.” They should have called it “Size Doesn't Matter.”25

They said small stocks often have shakier financial foundations. They have a tougher time weathering storms. Many can't, so they get dropped (or delisted) from the stock market. Shumway and Warther say that when we measure small‐cap returns, the data is rose colored. We only see the results of the survivors.

Ted Aronson manages institutional money through AJO Partners. He manages two small‐cap funds. They have each earned strong returns. So does Aronson believe in the small‐cap premium? Nope. Interviewed in 1999 by Jason Zweig, Aronson said, “Small‐caps don't outperform over time…. Sure, the long‐run numbers show small stocks returning roughly 1.2 percentage points more than large stocks…. [But] the extra trading costs easily eat up the entire extra return—and then some!”26

Some people might argue that their small cap index has outperformed the market. Vanguard's Small Cap Index (NAESX), for example, averaged 7.16 percent for the 10 years ending June 20, 2017. It beat Vanguard's S&P 500 Index (VFINX), which averaged 7.05 percent.27 These returns include trading costs, spreads, and any delisted stocks. So do small stocks beat large ones?

Ken Fisher says no. Sometimes smaller‐company stocks outperform. Other times, they don't. Small stocks usually do well early in a bull market (when stocks are starting a period of high growth). But they often disappoint when the bull is running on fumes.28

Does It Really Work Like That?

The firm Research Affiliates is always looking for a performance edge. They created the Fundamental Index in hopes of beating traditional cap‐weighted index funds. Their researchers Jason Hsu and Vitali Kalesnik researched the apparent small‐cap premium to see if small stocks really outperform. Based on their research, it appears that they don't.

Following Fama and French's research method, they split stocks into two groups for a variety of different countries. The largest 90 percent were put in one group. The smallest 10 percent were put in the other. They examined performances from 1926 to 2014.

After adjusting for extra transaction costs and delisting bias, Research Affiliates' Vitali Kalesnik and Noah Beck say small stocks don't beat large stocks at all. “If the size premium were discovered today, rather than in the 1980s, it would be challenging to even publish a paper documenting that small stocks outperform large ones.”29

I decided to check five‐year periods for US stocks back to January 1977. Using Morningstar, I compared Vanguard's Small Capitalization Index Fund (NAESX), comparing it to Vanguard's S&P 500 Index (VFINX). The S&P 500 is a large‐stock index. As shown in Table 10.4, over the eight different periods, the small‐stock index won four times. The large‐cap index won four times. When I measured the total 40‐year time period, it was close to a dead heat.30

Table 10.4 Small Stocks and Large Stocks Go Toe‐to‐Toe

SOURCE: Morningstar.com.

| Time Periods | Large Stocks (VFINX) Five‐Year Average Return | Small Stocks* (NAESX) Five‐Year Average Return | Winner |

| 1977–1982 | 8.1% | 16.4% | Small stocks |

| 1982–1986 | 15.8% | 9.7% | Large stocks |

| 1986–1991 | 13% | 0.6% | Large stocks |

| 1991–1996 | 16.5% | 21.4% | Small stocks |

| 1996–2001 | 18.3% | 11.4% | Large stocks |

| 2001–2006 | 0.5% | 9.1% | Small stocks |

| 2006–2011 | 2.2% | 5.5% | Small stocks |

| 2011–2017 (6 years) |

15.1% | 14% | Large stocks |

| 1977–2017 (40 years) |

10.82% | 10.88% |

Note: Vanguard's small cap index was an actively managed small cap fund until 1989.

Based on actual fund returns, it's tough to argue that small stocks have any long‐term advantage.

What If You and Your Spouse Represent Different Nationalities?

The following chapters provide sample portfolios for DIY investors based on different nationalities. Couples who represent different nationalities have choices:

- Build two portfolios. Each could represent the couple's relevant nationalities. This is what my wife and I chose to do. She's American. I'm Canadian. Each portfolio is taxed differently. Having two portfolios also provides easy access to immediate money when one of us dies.

- Build a single portfolio that blends the components of each respective portfolio. I don't recommend this for couples when one of them is from the United States. Americans are taxed on worldwide income and must pay capital gains taxes on non‐tax‐deferred accounts. They aren't eligible to open accounts with non‐American brokerages located in capital gains–free jurisdictions. But when the couple represents different (non‐American) nationalities, they could create a joint account.

- Build a single portfolio that focuses on the country that the couple might choose to retire in. For example, if an Australian and a Canadian plan to retire in Canada, they could build a portfolio that represents a Canadian bias, such as what you'll find in Chapter 12. If they wanted to retire in Australia, they could build a portfolio with an Australian bias, such as what you'll find in Chapter 14.

- Build a single, globally diversified portfolio that has no home‐country bias. Out of convenience, I've chosen to call these Global Nomad portfolios. Such portfolios would work well for couples that don't know where they want to retire. They would also suit couples retiring in an emerging‐market country. Emerging‐market countries have small, volatile markets. Retirees who choose to invest with a “home‐country” emerging‐market bias would be taking unnecessary risk. Instead, they could spread their risk across a multitude of global economic regions. I've provided samples of such portfolios in each of the following chapters.

Could Index Fund Investing Become Too Popular?

Popularity isn't always good. Sometimes, it creates a delusion that nothing can go wrong. Popular music and movie stars give us great examples. Famous people who start to believe they're actual demigods sometimes end up wrecks.

The media does its part to encourage their delusion. But when news networks sense blood, they often swoop in and attack. So what's the investment world's equivalent? It might be index funds.

CNBC reported that Americans piled $236.7 billion into index funds in 2016. In contrast, they treated actively managed funds like two‐week‐old bread. They pulled $263.8 billion out of actively managed funds in 2016.31

According to Morningstar, investors had a whopping $581 billion in Vanguard's Total Stock Market Index (VTSMX) in August 2017. Investors had $329.3 billion in Vanguard's S&P 500 Index (VFINX). Vanguard is now the world's biggest mutual fund company. No other mutual fund company comes even close.32

Vanguard used to battle Fidelity and American Funds. But according to Investment News, with almost $3 trillion under management, Vanguard almost has as much money under management as the other two companies combined.33

It's easy to see why index funds are popular. According to the SPIVA Scorecard, the S&P 500 Index beat 92.15 percent of actively managed large‐cap funds over the 10‐year period ending December 31, 2016. The S&P Mid Cap 400 Index beat 95.4 percent of actively managed mid‐cap funds. The S&P Small‐Cap 600 beat 94.64 percent of actively managed small‐cap funds.34

That said, some financial experts say there's a dark side to investing with index funds. They say the popularity of index funds has created its own problems. Michael Blanding, writing for Forbes magazine, quoted George E. Bates, professor and senior associate dean for International Development at Harvard Business School. He said, “We are now in a situation where index investors are the major shareholders in most of the large‐ and medium‐sized public companies in the United States. That raises the question, who is exercising control in these corporations?”

George Bates argues that a company's management might become complacent if it doesn't have to impress individual shareholders. In theory, if most of a company's ownership comes from index fund investors, the company's stock price will rise in proportion to its weighting in the index. If a company's management team makes plenty of mistakes, it won't be accountable for those mistakes. The share price could keep rising (if people keep buying the index) even if the company's management makes dimwitted decisions.35

Reality, however, will likely intervene. If a company's share price stops reflecting its business profits or losses, active investors will recognize that the stock is mispriced. For example, if somebody offered you $2 for the $1 in your pocket, wouldn't you want to sell?

Most sane people would. Fortunately, there are still plenty of people looking for mispriced stocks. Vanguard's Chris Philips says most of the money in the market isn't invested in index funds. Referencing Morningstar, he says:

Index funds constituted 14 percent and 3 percent of equity and fixed income funds, respectively, in market‐capitalization terms. That means more than 85 percent of the equity market and more than 95 percent of the bond market were invested in some form of active management, be it individual securities, hedge funds or managed accounts.36

Indexing doesn't appear to be at the point of taking over. But some people ask, “What if everybody indexed?” First of all, humans aren't that rational. There will always be millions of people or institutions that want to pick their own stocks.

But let's assume pigs start to fly and the entire world decides to build a portfolio of index funds. If that happened, the prices of stocks, relative to their intrinsic values, would get completely out of whack.

For example, a company that didn't increase its business profits—while experiencing an ever‐rising stock—would catch the eye of opportunists. They would swoop in to sell or short the stock. As their active trading generated more success, others would soon follow. As a result, it would once again make the markets more efficient.

Index investing has also taken on many roles. There are high‐dividend‐paying indexes; equal‐weighted indexes; value indexes; growth indexes; and small‐cap, mid‐cap, and low‐volatility indexes. Even among index fund investors, the flow of investment money rarely moves to the same place. Smart beta investing will unwittingly do its part to keep the market fairly efficient.

Index funds might be popular among retail investors. But just 14 percent of investable money sits in index funds. That's a small percentage, considering they've been around for more than 40 years.

What If I Need Help Building My Portfolio?

My next chapters explain which index funds you should buy, based on your respective nationality. But what if you have trouble? Perhaps you're having a tough time opening your brokerage account. Perhaps you don't know how to make an online purchase. Maybe this book went out of print (after selling a gazillion copies) and you can't remember which ETFs I suggested that you buy.

If you're faced with any of those issues, contact PlanVision's Mark Zoril. For an annual consulting free of just US$96 per year, he helps everyone, regardless of nationality.

- Tel: 1 (855) 965 4286

- E‐mail: [email protected]

Let's Go!

If you can control your emotions, let's get this going. Jump to the chapter pertaining to your nationality or where you want to retire. I'll explain exactly which ETFs to buy so you can build a diversified portfolio of index funds.