Chapter 4

Don't Let a Fool or a Psychopath Wreck Your Future

Anthony Bruno is the author of Iceman: The True Story of a Cold‐Blooded Killer. It's about Richard Kuklinski. He was a contract killer who often worked for the mob. He was nicknamed Iceman because he sometimes froze the bodies that he killed. He wanted to make it tough for investigators to determine the time of death.

Kuklinski was a psychopath. But many of his neighbors thought he was a decent guy. He could murder somebody in the morning. Later that day, he could host a neighborhood barbecue. Psychopaths lack empathy. But there's something even more alarming. They're sometimes the most charming and charismatic people you'll meet.1

Robert D. Hare is a researcher in the field of criminal psychology. With psychologist Paul Babiak, he co‐authored, Snakes In Suits, When Psychopaths Go To Work.2 Dr. Hare estimates that psychopaths make up about 1 percent of the human population.

Most psychopaths don't kill people and put them in their freezer. But they lack empathy and they're often great pretenders. Dale Carnegie's book How to Win Friends and Influence People can show them all they need to know to build trust with other people.3 Psychopaths usually strike after they've built that trust. Sometimes, they con people out of money. Other times, they prefer to create social chaos.

Many learn to ask great questions. They listen. Like a master salesperson, they might learn your birthday and your children's birthdays. They might send gifts, take you out for dinner, or pay for rounds of golf with a charismatic smile.

Dr. Robert Hare diagnoses psychopaths based on a list of 20 traits. Five of them include superficial charm, an overly high level of self‐worth, pathological lying, cunning and a lack of remorse.4

If you've been sold an offshore investment product, some of these traits might seem familiar. A charming man (it's almost always a man) likely convinced you to invest. Perhaps he cold‐called you at work. He might have taken you out for dinner, bought you tickets to a sports game or showed a velvet‐tongued interest in your health and well‐being.

I'm not saying everyone who sells an offshore investment scheme has a mental screw loose. But if they were honest about the products they sell, few people would invest in them.

This would be a truthful pitch for a typical offshore investment scheme.

If you invest $2,000 a month in the scheme I'm offering, I'll get an up‐front commission of about $27,000. Some of that will go to my employer. But most of it will go to me. You might not realize this, but to maximize my commission, I have to maximize the term. That's why 25‐year investment terms are my favorite. As soon as you start investing, I get paid the full commission up front.

You won't be able to sell all of your investment before a predetermined date without paying a massive penalty. That penalty might be 80 percent or more of what your portfolio is worth. To sell everything, penalty free, you'll have to keep the money invested for a period that might be as long as 25 years.

Even if you keep the money invested, you might not make a profit. You'll be charged nosebleed fees. Over a 10‐year period or longer, you stand little chance of beating inflation. I'm also not properly trained, so I don't know a lot about diversification. That means you might lose a lot of money over 25 years.

That doesn't sound appealing. But expats fall into these traps every single day. Financial salespeople rarely (if ever) reveal the entire truth. In 2015, The Telegraph's Katie Morley wrote Exposed: The Rip‐Off Investment “Advisors” Who Cost British Expats Billions.

She profiled a former employee of a large international advisory firm. He didn't have any financial training, beyond that of a week‐long course.

He alleged that the course included training to “psychologically manipulate customers into handing over their money.” He added, “We were told to prepare clients' paperwork and put it in blue folders. But after [the customer] had signed on the dotted line we'd slip extra pages into the folders that they hadn't seen before, which included details of the charges.”5

But they don't just target Brits. In 2015, a broker for The deVere Group approached Australian Tuan Phan in Abu Dhabi. The guy said Tuan should buy a Friends Provident Premier investment scheme. Its costs would have been more than 9 percent per year for the first 18 months. After that, costs dropped to about 4 percent per year. On average, that's 20 times higher than the cost of a global stock market index fund. Tuan didn't know that, but as he began to sign the documents, he knew something wasn't right.

The documentation said it was an investment scheme with an insurance wrapper. But he didn't want insurance. “I told the advisor it wasn't a suitable product for me,” he said. “I told him I didn't want it.”

The advisor then recommended another product. “What's the difference between this one and the other one?” Tuan asked.

The salesperson replied, “This is more suitable for you. It doesn't contain an insurance wrapper.” Unfortunately, Tuan says the guy performed a bait and switch. He used Tuan's original documents for the product he didn't want. Tuan had assumed that the previous documents (which contained his signature) were scrapped when Tuan said he didn't want the product. Without his knowledge, he had signed up for the original product—the one he had told the advisor he didn't want.

When Tuan learned that he had been duped, he complained to the regional head of the brokerage. According to Tuan, the regional leader said, “We have your signature and we got our commission from Friends Provident. Deal with them if you want a refund!”

Unfortunately, Friends Provident told Tuan to complain to deVere.6

The deVere Group Faces Trouble

In May 2017, Bloomberg profiled deVere. Journalists Zeke Faux, Benjamin Robertson, and Matt Robinson published “Firm Targeting Nest Eggs of UK Expats Faces SEC Probe.” The story explains how the US branch of the deVere Group was being investigated by the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) for charging commissions on products without having a license to do so.

Bloomberg also says a Singapore subsidiary of deVere was fined in 2008. They were using unlicensed advisors and selling insurance products without a license.

In 2016, a former deVere subsidiary in Hong Kong was fined for using unlicensed advisors and for failing to provide information to a local regulator.

In Japan, deVere is on a list of firms that are not authorized to solicit investors.

Bloomberg also reports that South African authorities are investigating deVere over undisclosed fees and commissions.7

The deVere Group might be one of the world's biggest sellers of expensive, inflexible, offshore investment schemes.

But What Type of Person Would Sell Such Schemes?

Such salespeople might fall under one of two categories:

Those with extremely low levels of financial education. They don't fully understand the products that they're selling.

Or

- Psychopaths or Machiavellians. They might understand the products. But they make them sound amazing so they can earn a big commission. They might know these products can ruin people's futures. But they simply don't care.

Expats Pay the World's Highest Investment Fees

American writer Upton Sinclair once said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”8

Many sales representatives flog offshore pensions from companies like Zurich International, RL 360, Friends Provident, Generali, Aviva, and Royal Skandia (Old Mutual) without realizing their clients are usually charged on three levels: annual management costs, establishment costs, and hidden mutual fund management fees. Sometimes, there are also “mirror fund” charges. These stab an extra pin in an already open wound.

Some of the more common brokerages selling offshore pensions include the deVere Group, Montpelier Financial Consultants, Austen Morris Associates, Globaleye Financial Planning, the Henley Group, Gilt Edge International, Warrick Mann International, the Alexander Beard Group, SCI Group Ltd., W1 Investment Group, Holborn Assets, and the Sovereign Group.

Many financial experts have believed for years that hedge funds charge the world's highest investment fees. But most expats pay more when they buy an offshore scheme.

At Berkshire Hathaway's 2016 Annual General Meeting, Warren Buffett slammed hedge funds for their outrageous fees. Hedge funds usually charge a management fee of 2 percent per year, plus 20 percent of any profits made. Table 4.1 shows how much hedge fund investors would pay per year based on different investment returns. Because hedge fund investors pay a percentage of the profits, the annual fees can change based on performance.9

Table 4.1 Hedge Fund Fees Based on Different Annual Gains

| Pre‐Fee Annual Gain | 2% | 5% | 8% |

| Result after 2% Management Fee | 0% | 3% | 6% |

| Deduction Equal to 20% of the Profits Made | 0% | −0.4% | −1.2% |

| Net Annual Gain after Fees | 0% | 2.6% | 4.8% |

| Total Annual Charges Paid | 2% | 2.4% | 3.2% |

Note the examples in Table 4.1. If a typical hedge fund gained 2 percent before fees, the investor would pay the 2 percent management fee, leaving the investor without a profit for the year. However, if the hedge fund gained 5 percent before fees, the investor would pay a 2 percent management fee, plus 20 percent of any profits earned. Profits would be 3 percent (5% gain minus 2% management fee) before management took its 20 percent cut. After management took its share of the profits, the investor would be left with a gain of 2.6 percent. As a result, the investor's total fees would be 2.4 percent that year.

Hedge funds perform poorly because they're so expensive (see the previous chapter for details).

Warren Buffett said that hedge fund compensation schemes are “unbelievable to me.”10

But expats who invest in offshore schemes pay much higher fees. By comparison, hedge funds are cheap.

Canadian Steve Batchelor invested in a Friends Provident investment scheme. It's one of the most common platforms sold to people who live abroad. Table 4.2 shows how Steve's annual investment costs compare to those of a typical hedge fund.

Table 4.2 Offshore Investment Schemes Cost More than Hedge Funds

SOURCE: Friends Provident Product Guide. www.fpinternational.com/products/premier‐advance.jsp.

| Annual Pre‐Fee Return | Annual Hedge Fund Fees | Estimated Friends Provident Premier Scheme Fees |

| 2% | 2% | 4%* |

| 5% | 2.4% | 4%* |

| 8% | 3.2% | 4%* |

* Friends Provident fees are higher than 9% per year for the first 18 months.

Paying investment fees of 4 percent per year might not sound like much. But Figure 4.1 shows the kind of damage it can cause. Imagine a one‐time investment of $10,000. If an investment, before fees, earned 8 percent per year, it would create a profit of $459,016 over 50 years. But if fees were 4 percent per year, it would create a profit of just $61,067 over the same time period.

Figure 4.1 How Could an Extra 4 Percent Annual Fee Hurt Your Returns?

SOURCE: www.wealthgame.ca/.

A Canadian Investor Gets Bled

Steve Batchelor knew nothing about offshore pensions when he moved overseas in 2001. The 42‐year‐old Canadian realized he couldn't contribute to a Canadian socialized pension plan while working in Beijing, so he welcomed the idea of investing in a private pension.

His employer encouraged it. But instead of providing educational sessions for staff about appropriate investments and fees, the employer invited some hungry offshore pension peddlers. “We were told,” says Steve, “that our employer would match some of our savings if we invested with one of the pension firms.”

Steve warmed to a representative selling a Friends Provident scheme. Describing the perks, the representative told Steve he could earn loyalty bonuses after the 10th year. He also said Steve could switch his money between funds at no extra cost, and that the money would grow tax free, offshore.

Steve felt confused by the advisor's explanation of the pension's inner workings: a percentage in fees taken here, a percentage taken there, reduced costs here, bonuses gained there. It looked messy. But Steve trusted the advisor. “I was really proud of myself for setting this up at first,” he said. “But I wish I knew then what I know now.”11

Steve's money was invested in actively managed mirror funds, costing an average of 2.5 percent a year. Not only was he paying high costs for the funds, but his first 18 months of savings will bleed for 25 years.

Steve invested $9,266 during the first year and a half. His Friends Provident Premier Advance plan charges 7.2 percent annually in fees for the first 18 months. External mutual fund costs deducted an additional 2.5 percent per year (the salesperson chose mirror funds, which charge extra hidden fees). Consequently, during his first year and a half, he paid gob‐smacking costs of 9.70 percent annually.12 Even if Steve's investments had made 9 percent a year (before fees) during this 18‐month period, Steve would have lost money.

As stated in the contract, Friends Provident would reduce Steve's annual charges by 6 percent on all deposits made after 18 months. But he's stuck paying costs of 9.7 percent per year for 25 years on the first $9,266 he deposited. If the money Steve invested during the first 18 months earns (before fees) 9.7 percent per year for 25 years, it will match Steve's investment costs. His initial $9,266 becomes a corporate Dracula's drinking fountain.

Some people donate to charity; others give to family. Few place financial firms on their philanthropic lists.

Investment Schemes That Cripple Like a Virus

Investing with actively managed funds is like walking up a downward‐heading escalator. Those doing so fight more than gravity. But many expats face the same daunting task with 80‐pound rucksacks. Like Steve Batchelor, they're sold debilitating offshore pensions, otherwise known as investment‐linked assurance schemes (ILASs). If you're an expatriate, chances are either you or someone you know has fallen into one of these schemes.

Advisors selling such products promise high, tax‐free returns. Americans aren't usually targeted, as they must declare their worldwide income to the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). For them, the “tax‐free” sales pitch smacks of Al Capone: The infamous gangster wasn't tossed into Alcatraz for bootlegging or murder—but for tax evasion.

Europeans, Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Asians, South Americans, and Africans, however, are ripe pickings for silver‐tongued sharks. If they're living in a country where they don't have to pay tax on foreign investment income (check with a tax accountant), many expats can legally invest offshore where capital gains aren't taxed. Many don't realize, however, that they can do so without buying an expensive, inflexible offshore pension.

Advisors selling such products earn commissions high enough to make a cadaver blush. Investors buying them get stiffed.

The investments are usually portfolios of actively managed mutual funds coupled with an insurance component. Neither the investment nor the insurance is typically worth the money.

To be fair, not all advisors selling offshore pensions understand their total costs. Question them about fees and they might dig into the fund prospectus, citing costs of 1.5 percent or less. Or they'll glibly state that the fees are low—without understanding the ravages beneath the surface. Offshore pensions commonly cost 4 percent or more each year.

Peggy Creveling, a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and Certified Financial Planner (CFP) based in Bangkok, says such products are long on promises and short on profits.

“What the sales literature does not expressly tell you may become clear—once you agree to purchase the scheme. Your investment is subjected to a layered fee structure that can lower your earnings significantly, perhaps by 30 to 40 percent per year.”13

Creveling is right. But the reality can be even worse. If global stock markets disappoint investors, earning just 4 percent per year over the next decade, many offshore pension investors would make nothing after paying 4 percent in fees.

This is based on the premise in the Stanford University published paper “The Arithmetic of Active Management.” Written by economic sciences Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe, it asserts that the typical actively managed dollar will underperform the market in direct proportion to the fees charged.14

Investors don't need to pay 4 percent in annual fees. Most expatriate investors could pay as little as 0.20 percent by building a portfolio of index funds. There's a 3.80 percent annual differential between paying 4 percent and paying 0.20 percent. But are the savings such a big deal? That depends on whether you want to retire on caviar or cat food.

Table 4.3 shows that after 15 years, a 3.80 percent annual difference between an indexed portfolio and an offshore pension (ILAS) would likely put 39 percent more in the index investor's pocket, 57 percent more after 20 years, 79 percent more after 25 years, 105 percent more after 30 years, and 137 percent more after 35 years. (See Table 4.3.) Over an expat's career, the difference could exceed one million dollars, one million pounds, or one million euros. We're not talking chump change.

Table 4.3 Results of $10,000 Invested Annually if Global Stock and Bond Markets Averaged 9 Percent

| Investment Duration | Indexed Portfolio Averaging 8.8% after Costs | Offshore Pension Averaging 5% after Costs | Paying 3.8% Less Each Year Would Earn |

| 15 years | $314,470 | $226,574 | 39% more |

| 20 years | $544,283 | $347,192 | 57% more |

| 25 years | $894,646 | $501,134 | 79% more |

| 30 years | $1,428,797 | $697,607 | 105% more |

| 35 years | $2,243,141 | $948,363 | 137% more |

British Expats: Can I Trade You That Diamond for a Big Lump of Coal?

Imagine that you're entitled to a British government defined benefit pension. Before moving abroad, you worked in education, the military, nursing, or had a different public‐sector government job. The British government says, “We'll give you a fixed monthly payment for life when you retire.”

Then you move abroad. A snake in a suit slithers up to your gate. “You don't want that pension; let me offer something better.”

You might wonder, “Who would want to get rid of their government pension?” But these snakes in suits possess septic silver tongues.

For a small number of people, it makes sense to cash them in and put the proceeds in a QROPS (qualified retirement overseas pension scheme).

But for most former government public sector workers, a QROPS doesn't make sense. Sarah Lord, head of financial planning at Killik & Co., a British FCA‐regulated firm, was quoted in The Telegraph saying, “The operation of offshore advisers, in the main, is totally unscrupulous.”15

I visited plenty of international British schools in 2017. Sadly, most of the teachers had cashed in their UK government defined benefit pension plans. One teacher, who worked at Abu Dhabi's Brighton College, cried when she told me. “I transferred £300,000,” she said, “but it's now worth only £180,000.” Other times, investors lost everything when the money was directed into a UCIS (unregulated collective investment scheme).

I asked Sam Instone, the CEO of AES International, if he has seen such examples. He took a deep breath. He then rolled his eyes and sighed, “We see this all the time … all the time.”16

UK‐based financial advisor Ben Sherwood joined Hillier Hopkins in 1997 and became a partner in 2002. He's a Certified Financial Planner and Chartered Financial Planner for high‐net‐worth clients. He also holds investment and taxation qualifications and he's a co‐author of The 7 Secrets of Money: The Insider's Guide to Personal Investment Success (SRA Books, 2013).

He was horrified to learn that many British expats cashed in their UK government teachers' pensions for QROPS schemes.

“The idea that most teachers with rights under the UK Teachers Pension Scheme should transfer is simply scandalous.” He says transferring to a QROPS rarely makes sense. “The right QROPS can be the right answer for the right client in the right circumstances. But in our experience the likelihood of these stars aligning is very rare.”17

I also asked Simon Glazier. The Chartered Financial Planner works for A+B Wealth. He won the United Kingdom's financial advisor of the year award in 2015.

“A pension transfer of this type is effectively a transfer of risk, from the government to the member,” he says. “For many people such a transfer of risk is unacceptable, especially where they do not have significant financial resources in addition to their pension scheme. Moving money into a high charge, poorly regulated substitute pension, recommended by an ‘adviser’ who is incentivised to sell one to you, will almost always be a poor choice.”18

Fortunately, the UK government has limited such transfers. Investors wanting a QROPS now pay a 25 percent tax. But for many expat teachers and former public‐sector workers, the damage has been done.19

Featuring the Rip‐Offers

Certified Financial Planner Tony Noto was once hired by a firm to sell offshore pensions to expatriates. But the more he learned about them, the sketchier they appeared. After two weeks of dissecting these products, he quit and established his own firm to build indexed portfolios for clients.

“These offshore pensions are popularly sold,” he says, “because they offer lucrative up‐front commissions, often equivalent to the total sum of an investor's deposit during their first year of the scheme. Those convincing you to invest $15,000 per year for 25 years, for example, often reap an up‐front commission of roughly $15,000 from the insurance company, shortly after the contractual ink dries. There is no question of who ultimately pays that bill—the investor.”20

Benjamin Robertson revealed the commissions paid to brokers in his September 2013 article in the South China Morning Post, “Investment‐Linked Insurance Schemes a Trap for Unwary Investors.” On a 20‐year policy, a broker convincing a client to add $1,000 per month ($12,000 per year) would receive an up‐front commission of $10,800, split between the broker and his or her employer.

On a 25‐year policy, the commission would be higher. It's based on a formula multiplying the number of years of the policy × 12 (months in the year) × monthly dollar contribution × 4.2 percent. A 25‐year policy in which the investor adds $1,000 per month would earn a brokerage commission of $12,600.21

Recognizing a winning lottery ticket when they see it, many expatriate advisors flog the products exclusively. To a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Consequently, these expensive, inflexible platforms have spread like pandemics among global expats.

The 10 Habits of Successful Financial Advisors…Really?

Former expatriate financial advisor Frank Furness created a series of training videos for advisors. One of them is titled “The 10 Habits of Successful Financial Advisors.” Not one of the habits deals with investors' welfare. Instead, the video outlines strategies expatriate advisors use to make millions of dollars a year in commissions. As Furness says, “For me, it's the best job in the world. Where else can I go out and meet somebody, drink their coffee, eat their cake, and walk out with $5,000 in my pocket? No other business.”22

Much like car salesmen, many measure success by how many deals they can close. In a different video, Furness interviews Steve Young, a representative working for International Financial Services (Singapore). Furness describes Steve Young as one of the region's top advisors—one of “the true tigers in the industry.” The advisor explains that his team puts prospective clients in front of him “to let me do what I'm good at, which is closing the deals out.”

Young adds, “If I can delegate the paperwork, all I want to do is see the checks from the clients.” The advisor is so good at selling, in fact, that he once established 198 new clients in a single calendar month, claiming to set a world record in the process. Furness closes the video by saying to the camera, “If you live anywhere in Asia, especially in the Singapore area, and you want to deal with the best … why not contact Steve?”23 Unfortunately, “the best” advisor in sales lore isn't necessarily the best advisor for clients.

When Your Advisor Is a Sales Commando

In April 2014, online publication International Adviser highlighted quotes from Doug Tucker's new book, Sales Commando: Unleash Your Potential (PG Press, 2014). Tucker, a former offshore pension seller, says that to generate clients “you have to go into full‐frontal attack mode. This means huge, massive action. To do this you need a strategy, a plan of attack, and the absolute certainty you are going to win.”

Before a prospective client can object to a product, Tucker suggests to advisors: “Create a mental picture of each objection as a small monster being born and figuratively popping out of the client's mouth. The minute you pay attention to the fledgling monster you will be feeding it with energy, because this little monster thrives on encouragement. The more you acknowledge its presence, the more it will grow and grow.”24

Lucrative up‐front commissions encourage such aggressive winner‐take‐all strategies. In some cases, advisors convince their clients to invest far more than they can afford. Such was the case with Sit‐Wai Long, a former HSBC Bank representative. He convinced a client with a comparatively low income to invest a ridiculously high monthly sum. Fortunately, he was caught. Hong Kong regulatory authorities slapped him with a three‐year suspension from selling financial products.25

While the city's customer complaints about offshore pensions doubled in 2013 compared to 2012, much of the abuse still gets unreported.

Welcoming Sharks into the Seal Pool

Few expatriate employers understand how offshore pensions work. Yet many invite sharks into the company seal pools. Chip Kimball, superintendent at Singapore American School, says, “Many international schools don't have any form of regulation, and little to no vetting or oversight regarding the financial products that salespeople try selling on campuses.” Some schools embrace expensive, inflexible official providers, while encouraging staff to use them. “This is dangerous,” adds Kimball. “High fees and commissions for poor financial products cost teachers dearly.”26 International teachers aren't the only expats at risk.

Here's how the process often begins. A representative from a brokerage firm slides into a workplace.

The broker convinces management to endorse the broker's firm, resulting in a ready‐made customer base. Such brokers are intermediaries for offshore pension providers, many of which are based in the British Channel Islands, Luxembourg, or the Isle of Man.

This is what happened, years ago, at the Western Academy of Beijing (WAB). The administration, at the time, didn't know the difference between a legitimate financial advisor and a shark in a suit. I spoke at the school in 2015. The administration had offered to match part of the employees' savings into an investment plan. But the plan had to be on the school's approved list. Unfortunately, that list included brokerage firms that sold expensive offshore pensions. None of the firms on the list charged low fees. In each case, they sucked teachers and administrators into long‐term, expensive offshore investment schemes.

Even the Americans fell victim (which Uncle Sam wouldn't like).

After the teachers had learned what they had done, there was little they could do. Such firms pay huge commissions to the brokers who sell the products. To recoup that commission, firms like Friends Provident, for example, must keep the investor's money as long as possible. Doing so allows the company to reap more fees over time. As an investor adds more money, fees mount. But investors awakening to the tyranny of costs find their private parts stuck in a zipper. Early redemption penalties might cost 80 percent (or more) of the investor's total proceeds.

Jon Williams, formerly a British information technology (IT) worker in Dubai, explains how these offshore pensions can gain traction away from the workplace. “A friend of mine gave my contact information to an advisor working for PIC [Professional Investment Consultants]. It's an affiliate of the deVere Group.” Jon met the representative in his apartment. “I wanted a breakdown of costs,” says Jon, “so the advisor promised to send it the following day.”

In return, the advisor wanted the names and contact details for 10 of Jon's friends or colleagues. “I felt Jedi mind‐tricked by the guy and did what he asked.” The following day, Jon received the breakdown of fees, entered the particulars into an Excel spreadsheet, and was horrified by the costs. “I didn't sign up, even though the rep told me he was offering a special one‐time offer—one that needed an immediate decision.” Promises of urgent, one‐time offers should always raise red flags, whether you're buying financial products or a holiday time‐share. Jon also asked the advisor not to contact his friends. “I made a lucky escape. But many of my friends weren't as fortunate.”27

Let Me Offer You a Free Trip to the Maldives

Early in 2017, a financial salesperson sent Matthew Backus an unusual e‐mail. She offered the Canadian a free trip for two to the Maldives.28

Matthew and his wife are educators. They live in Dubai. The Maldives would have offered a nice break from their giant urban sandbox. He just needed to introduce the financial advisor to some of his friends. She wanted a list of 10 names that included e‐mails and phone numbers. If Matthew had agreed, he and his wife would have been on their way to the Maldives, with all expenses paid.

But Matthew didn't bite. He feared that if he gave her the names of his friends (even if he had warned his friends ahead of time), she might have convinced one of them to invest in an offshore investment scheme. If that actually happened, it would have been Matthew's fault.

If Matthew's friend had invested in such a scheme, his friend's annual investment fees would have exceeded 4 percent per year. If his friend had tried to fully redeem his money after a few years, he would hit a brick wall. He might be locked in for 25 years. If he tried to sell early, he might lose more than 80 percent of his investment proceeds.

In 2017, I gave investment talks in 11 different countries. I was speaking about the benefits of low‐cost index funds. I said people should avoid expensive offshore schemes. Some financial advisors (I prefer to call them salespeople) earn more in a week than the typical teacher earns in a year. That's why they sometimes offer concert tickets, hotel stays, iPads, or free trips to the Maldives in exchange for phone numbers.

For example, if an advisor had convinced one of Matthew's friends to invest $2,000 a month in a Friends Provident scheme, she would have earned an up‐front commission of about $27,000. That's according to Sam Instone, CEO of the financial services company AES International. He says the advisor would have netted about $17,000 after her brokerage received its share.

Misled Investors Pay the Price

High‐commission‐paying products often distract advisors from telling the entire truth. Those selling offshore pensions should always discuss withdrawal penalties. Not doing so, unfortunately, is common.

Indian national Alla Rao was working in Abu Dhabi when he met an agent selling a Zurich International Vista offshore pension. As he explains, “After constant pestering by the advisor and after him showing me charts representing great investment returns, I ended up signing. Never a word was mentioned about early surrender penalties. I was told I could sell the Zurich policy anytime, with a maximum surrender cost of 1 or 2 percent. But despite rising global stock markets during my 4.5 years of owning the plan [global stocks rose 40 percent], my investments had dropped 10 percent. I've since learned that to sell will cost me 33 percent of everything I've invested, from early redemption penalties. The advisor certainly never told me that when he sold me the plan.”31

Would You Like a Band‐Aid for That Bleeding Gash?

Sometimes, these investment schemes offer loyalty bonuses. Such is the case with the Friend's Provident plan that Steve Batchelor bought. It pays loyalty bonuses of 0.5 percent annually. But it's a small Band‐Aid for a bleeding gash. Steve's total annual charges on deposits made after the 18th month are six times greater than the bonus offered. Charges on the deposits made during the first 18 months continue to exceed 9 percent per year—more than 18 times higher than the 0.5 percent bonus offered by Friends Provident after the 10th year.

Investors building a low‐cost portfolio of index funds costing just 0.2 percent per year (and I'll show you how to do this) would likely have much more money than Steve would at the end of the 25‐year term. Unlike Steve, they would also have the flexibility to sell their investments without penalty at any time. And as long as their home or resident country doesn't tax them on worldwide income, they wouldn't have to pay capital gains taxes. I'll explain how in subsequent chapters.

Masters of the Insured Death Benefit Illusion

Those flogging offshore pensions, however, may point to the insured death benefit. It's often craftily worded. This was Steve's:

In the event of the death of the Life Assured (or the last surviving Life Assured if the policy is written on more than one life) while the policy is in force, 101 percent of the cash‐in value of your plan will be payable.

The literature accompanying the policy offered no other reference or explanation of what this meant. So I wondered: Did it mean the deceased earned a 101 percent bonus on top of the investment portfolio's actual value?

I had to call four separate advisors flogging Friends Provident pensions before one of them even attempted to explain the insurance policy. He said that if the policy holder (the investor) dies, then his or her heirs would receive the account's proceeds, or if the account were valued less than what was deposited into it, the surviving members (spouse, brother, sister, whoever was on the policy) would earn an amount equal to 101 percent of what the deceased had invested.

Manipulation with numbers is an art. The contract claims the descendant receives “101 percent of the cash‐in value.” But consider this. If I loaned you $5 and you gave the $5 back, you would have returned 100 percent of what I had loaned you. By offering 101 percent of the “cash‐in value,” Friends Provident offers to pay back 1 percent more than what was invested: not 1 percent per year, but 1 percent overall. There's no upward adjustment to cover inflation. If inflation averaged 3.5 percent per year, the insurance guarantee equals a real (inflation‐adjusted) loss exceeding 40 percent for the decade, if the investor died while the portfolio was worth less than what he or she had deposited.

Free Fund Switching Isn't a Perk

Sales reps also promote the idea that clients dissatisfied with their fund performances can switch into other funds for free. Costs to switch into different funds are called sales loads. In a 2012 Bloomberg.com article titled “The Worst Deal in Mutual Funds Faces a Reckoning,” Ben Steverman writes, “Those paying loads are the poorest and least sophisticated of investors.”32 Only the naïve would believe that free fund switching is a perk. Load fees are as easy to avoid as a 10‐foot‐wide drainage ditch.

Such costs are even banned in Australia and the United Kingdom.33

Expatriate workplaces, however, aren't the only feeding grounds for commission‐hungry sales reps; some do almost anything to build a client base. Random cold calls aren't beneath them. A sales representative from Austen Morris Associates cold‐called Icelander Lawrence Graham just three to four months after he became an expatriate.

“I have no idea how he found my number,” Graham says. “The rep explained the expected returns over the next few decades and made it all sound fairly good: low expected returns for the first few years with exponential growth in the later years of the plan due to the larger amount of money that would have been invested by that point. But there's a lot they didn't tell me. I had no idea how much the fees would eat into my profits. The money I gave them during the first 18 months has to stay with the firm for 30 years. I can't take it out earlier without paying a hefty penalty. They didn't tell me that when I signed up.”34

Making Millions off the General Public

With such massive commissions paid to brokers, sales of these products won't likely abate any time soon. When BBC Panorama investigated one of the largest offshore pension sellers, deVere Group, the investigators revealed that the company's top sales brokers earned on average more than £220,000 in the first three months of 2010. The top broker was on track to exceed £1 million for the year.

Penny Haslam reported such findings in the BBC Panorama documentary Who Took My Pension? After asking pension providers to supply data on charges, she revealed the most expensive pensions in Great Britain.

Here's how they stacked up if investors had contributed £120,000 over 40 years. Legal and General's Co‐Funds Portfolio Pension would have taken £61,000 in fees, the Co‐operative Bank's Personal Pension would have absconded with £95,900 in fees, and HSBC's World Selection Personal Pension would have lifted £99,900 in total fees.35

The documentary included costs of management fees in these calculations, but didn't include costs of actively managed funds within the pensions themselves. Doing so would have doubled total fees, aligning them closely with offshore pension costs.

Fooling the Masses with Numbers

While the offshore pension providers have subtle differences, most seduce investors with the promise of loyalty bonuses. But it's a smoke and mirrors show.

To dramatize an example, I'll introduce you to a hypothetical bonus platform that's far more generous than anything offered by an offshore pension. It's going to look amazing. But don't be fooled.

Hallam's offshore pension guarantees a 50 percent bonus on unlimited cash deposits. If you invest $10,000 each year, we'll chip in an extra 50 percent, ramping your invested proceeds to $15,000 per year.

Annual management charges are just 1.5 percent per year. How can you lose when receiving a 50 percent annual bonus?

In this fantasy broker scenario, I haven't included costs of the actively managed funds. If the fund expenses added another 2 percent per year, total costs for the account would run 3.5 percent per year (1.5 percent for the management fee plus 2 percent for the mutual funds).

Still, that 50 percent bonus appears to trump the comparatively small 3.5 percent annual account charge. Or does it?

Keep in mind that no offshore pension firm offers a 50 percent bonus every year on annual deposits. But even if one did, investors could still get fleeced. Deception with numbers is an art. Not receiving a bonus but paying just 0.2 percent in annual fees would reap far greater rewards.

Table 4.4 lists the fantasy bonus pension alongside an indexed portfolio.

Table 4.4 Bonuses Don't Offset Costs

| Investor Has $10,000 per Year to Invest | Fantasy Offshore 50% Bonus Pension | Low‐Cost Indexed Portfolio |

| Amount annually invested by client | $10,000 | $10,000 |

| Annual bonus paid on deposits | 50% | 0% |

| Total annual amount invested after bonus | $15,000 | $10,000 |

| Assumed global markets' average return | 10% | 10% |

| Annual fees paid on total portfolio value | 3.5% | 0.2% |

| Annual returns after fees | 6.5% | 9.8% |

| Total portfolio value after 30 years | $1,379,838 | $1,739,129 |

No offshore pension provider offers a 50 percent annual bonus on unlimited deposits every year. But even if one did, the investor could still end up hundreds of thousands of dollars poorer.

Regulators Making an Effort

Attractive distractions sold as “bonuses” or “fee reductions” have caught the attention of Hong Kong's Monetary Authority. In March 2011, Meena Datwani, Chief Executor for Banking Conduct, distributed a memo to the city's ILAS product sellers. Complaints about offshore pensions had caused regulators to set certain requirements for the products. But despite the effort, interpretations of fees, bonuses, and promises vary. Consequently, they're difficult to enforce.36

Hong Kong's Monetary Authority worded its restrictions the following way:

Use of Gifts or Promises of Reduced Fees over Time

To avoid distracting customers' attention from the nature and risks associated with ILAS [offshore pension] products, AIs [authorized institutions] should not offer financial or other incentives (e.g., gifts) for promoting ILAS products. Discount of fees and charges, and the offering of any gifts for brand promotion, relationship building, or other purposes….

Bonuses and reduced fee offerings can distract customers from the unflattering reality of fees incurred. But what the sales representative doesn't state might be more harmful than what is stated.

Lock‐In Periods

AIs [authorized institutions] should disclose and explain that ILAS [offshore pension] products are designed to be held for a medium/long‐term period and that early surrender of the product may be subject to a heavy financial penalty, and disclose the level of penalty.

When I dissected the inner workings of offshore pensions on my blog (www.andrewhallam.com), hundreds of investors holding such products left messages claiming that nobody had explained the penalties incurred if they sold their investments before the termination date of their policy. Not disclosing this information may have helped sales reps close their deals. But it hurt the many investors who required earlier access to their money.

Fees and Charges

Fees and charges—AIs [authorized institutions] should disclose and explain the fees and charges at both the scheme level and the underlying investment asset level, and that due to the fees and charges, the return on the ILAS [offshore pension] product as a whole may be lower than the return of the underlying investment assets.

Many sales reps fail to mention total charges: the management fees for the portfolio plus the hidden expense ratio costs of the funds themselves. As such, many cite costs of 1.5 percent to clients, when actual costs usually exceed 3.5 percent per year. Would any dare show what a 3.5 percent annual drag on investment returns would do over time?

Even though Hong Kong regulatory authorities distributed the preceding restrictions, they don't appear to be enforced.

You might wonder how prolifically offshore pensions are sold. Reporter Nicky Burridge of the South China Morning Post wanted to find out. She generously detailed her findings here.

Record Complaints in the UAE Are Gaining Some Attention

In May 2017, The National reported that the UAE government sent out a circular in response to “an increasing number of complaints in relation to the savings and investment insurance products.”

The circular described the schemes as “complex in nature and not well understood.” The government says finance companies must settle their customer complaints within a 90‐day period.

The National says, “This is part of a wider clampdown on questionable sales practices, with the insurance authority announcing that it was pushing ahead with tough new regulations to offer UAE investors better protection against the mis‐selling of these products by financial advisors.” The article says experts describe these products as “the most expensive financial products sold anywhere in the world.”37

Sadly, such products are commonly sold throughout Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East and sometimes in Europe.

Can Squeaky Wheels Gain Redemption?

While inappropriate selling of these high‐commission products is likely to continue, squeaky wheels occasionally gain attention.

On October 24, 2010, 24‐year‐old Tsang Sau Ming (known by friends as DeAnn) invested with a firm called Convoy Investment Services in Hong Kong.

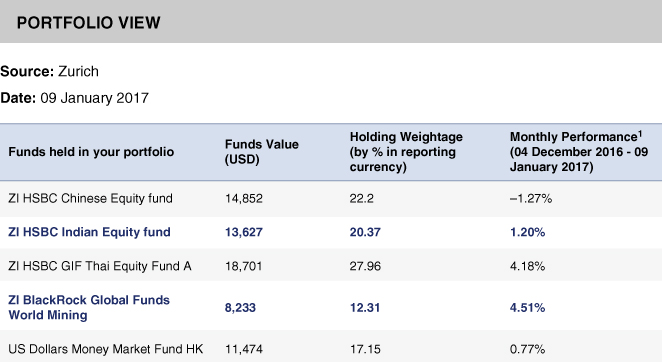

The Convoy rep sold her an offshore pension through Zurich Vista, coupling an insurance policy with a high‐cost investment platform. The advisor dismissed her insistence that she didn't need an insurance policy, and he recommended that she invest 28.6 percent of her HK$126,000 annual salary.

During the first 18 months, she invested HK$54,000, increasing her invested total to HK$93,000 midway through 2013. During that time period, the US stock market gained 50 percent; global stock markets averaged a 25 percent gain. But anchored by heavy administrative fees, high fund costs, and poor fund selection, DeAnn earned less than 1 percent.

Upset with her account's performance and the realization of the costs paid, she inquired about selling her investment policy. But while her statements claimed she had $93,500, Zurich was prepared to give her only $43,000. The remaining $50,500 would be absorbed as a penalty for redeeming her funds early.

Distraught, she contacted Leung Chung‐yan, who battled her own offshore pension by going to the media.38

Although Leung Chung‐yan didn't receive an apology from the firm for wrongdoing, she was offered a full refund.

The offered refund gives hope to many, including DeAnn.

Another precedent‐setting investor was a 59‐year‐old British expatriate living near Alicante, Spain. He saw his savings plummet from £89,000 to just £20,000 after purchasing an offshore pension offered by the deVere Group in June 2010. He wanted to withdraw his remaining money but was told by deVere that he would receive only £11,000 after charges. Rightfully upset, he took his story to the UK financial blog site, This Is Money. Media pressure caused deVere to cave. They reimbursed his entire £89,000.39

Should You Ditch Your Offshore Pension?

It's a question many investors in similar predicaments have asked themselves. Should they redeem their investments (taking a kick to the groin) or continue contributing to the plan while getting fleeced by high fees?

Many investors have taken a voluntary kick to the privates by selling their funds before the policy surrender date. They argue that, by doing so, they could invest the leftover proceeds in a low‐cost platform and still come out ahead.

Here's an example using DeAnn's scenario. Her policy's fee structure is characteristically murky, but total annual costs (including fund fees) run roughly 3.8 percent per year.

If global markets generate a 9 percent return, she would likely reap about 5.2 percent, as long as her advisor allocated the funds intelligently. Consequently, her HK$93,500, coupled with her annual deposits of HK$35,280 for the next 22 years, could grow to HK$1,748,608.

But taking a financial hit and selling her policy might be the better option. If she took a HK$50,500 penalty for canceling the policy, she would have HK$43,000 remaining. If she paid annual investment fees of 0.2 percent, she could earn 8.8 percent annually on that HK$43,000 if global markets grew by 9 percent. Over 22 years, while adding HK$35,280 annually, she could grow her money to HK$2,622,854 (see Table 4.5).

Table 4.5 Would DeAnn Be Wise to Take the Financial Hit?

| DeAnn Pays Redemption Fee and Invests the Remainder | DeAnn Remains with the High‐Cost Investment | |

| Investment value | HK$43,000 (amount remaining after redemption penalties) | HK$93,500 |

| Annual addition | HK$35,280 | HK$35,280 |

| Estimated growth rate after fees | 8.8% | 5.2% |

| Value of portfolio after 22 years | HK$2,628,190 | HK$1,748,608 |

Despite taking a $50,500 penalty for canceling her policy, she could invest the reduced sum but still retire nearly a million dollars richer by paying lower investment costs.

If you're pondering your own offshore pension predicament, do the math with a compound interest calculator, such as the one at www.moneychimp.com. Understand all of the fees first, along with any bonus units you might be entitled to. Some money could be eligible for a free withdrawal, so contact your advisor about softening redemption costs. After doing so, you could determine whether it's worth hanging on to your policy, taking the hit and canceling, or limiting the damage by simply reducing (or eliminating) new deposits if the policy allows it.

When High Fees Meet Gunslingers

Unfortunately, high costs aren't the only problem with offshore pensions. Many advisors selling them fail to build diversified portfolios. Diversification increases safety. Stuffing too many eggs into the same basket increases risk. And when the basket tips (all baskets tip at some point), the investment portfolio cracks.

Most offshore pension sellers aren't Certified Financial Planners (CFP) or Chartered Financial Planners. The CFP designation ensures that advisors have been trained to diversify their clients' money, spreading it across multiple asset classes and geographic regions. Instead, many offshore pension sellers obtain impressive‐sounding three‐letter credentials that require fewer than three weeks to obtain.

Former broker Shawn Wong says,

People wanting to sell ILAS products [offshore pensions] don't require strict financial training. The firm I worked at often sold Friends Provident, Zurich, and Standard Life products because they offered high commissions and low‐level entry points. Someone directly out of high school could pass the required licensing tests in a couple of weeks. The tests are easy, with minimal focus on multi‐asset‐class portfolio allocation and rebalancing. Not surprisingly, many client portfolios get built without adequate diversification. The focus on sales and commissions outweighs the need for a responsible portfolio.40

Odds are that those investing with a Certified Financial Planner (CFP) or a Chartered Financial Planner won't suffer from a lack of diversification. But CFPs aren't all saints. Such an advisor looking for fat commissions could still push your money into an offshore pension. However, CFPs are more likely to diversify their clients' accounts across global stock and bond markets—instead of gambling everything on a few pet sectors.

A Son's Inheritance Gets Plundered

Spaniard Miguel Delgado (not his real name) unfortunately employed an egg basket stuffer. A teacher at an international school in Vietnam, he invested 250,000 euros with an advisor from the SCI Group.

Miguel wanted to invest the money conservatively. His mother had recently died, and the money had come from his inheritance. Having already lost his mother, he couldn't bear the thought of losing her hard‐earned money as well. Unfortunately, the advisor convinced him to invest his entire inheritance, plus a further 50,000 euros his wife had saved, into PDL International's Protected Asset TEP Fund (PATF). Failing to diversify is like doing the high jump with a pair of scissors. Daniel R. Solin, the author of Does Your Broker Owe You Money?, says when a broker fails to adequately diversify a client's portfolio, it's cause for a lawsuit.41

Miguel's advisor described the investment as a fund endowment policy promising broad diversification, low volatility, and consistent returns. The trouble was, Miguel didn't know what endowment policies were. But the advisor had a silver tongue. Miguel, hooked by the salesman's suavity, unknowingly compounded the tragedy. “I convinced my brother to invest his inheritance in the fund as well.”

The investment was supposed to be far safer than a regular stock market fund—or so the sales pitch went. It wasn't supposed to drop, even if the stock markets fell. This greatly appealed to Miguel. The money his mother bequeathed was sacred. He didn't want to lose it.

But in 2008, the investment collapsed, dropping 35 percent in 12 months. The United States was the catalyst for the financial crisis, but not even its stock market dropped as far. In euro terms, US stocks fell roughly 30 percent. They soon recovered, and by 2014, US stocks were 50 percent higher than they were before the financial crisis hit.

Unfortunately, the same can't be said for PDL International's PATF fund. By May 2017, it had not fully recovered from its 2008 plunge.42

Miguel explains, “When the fund started to rise again, we sold, losing 80,000 euros in a fund that was supposed to be conservative.” He claims, however, to have learned his lesson. “Promises of strong returns without risk don't exist, despite what a smooth‐talking salesperson might tell you. It's important to fully understand what you're invested in.”

Steve Batchelor—the Beijing‐based Canadian expat I introduced earlier—also suffered from a lack of diversification. He bought a Friends Provident offshore pension through a firm called Gilt Edge International.

Steve started his offshore pension in late 2007. It didn't have any exposure to US stocks (the world's largest market) or European stocks. Nor did it have exposure to bonds. Portfolios such as Steve's are like rock climbers without ropes: exciting perhaps, but irresponsible.

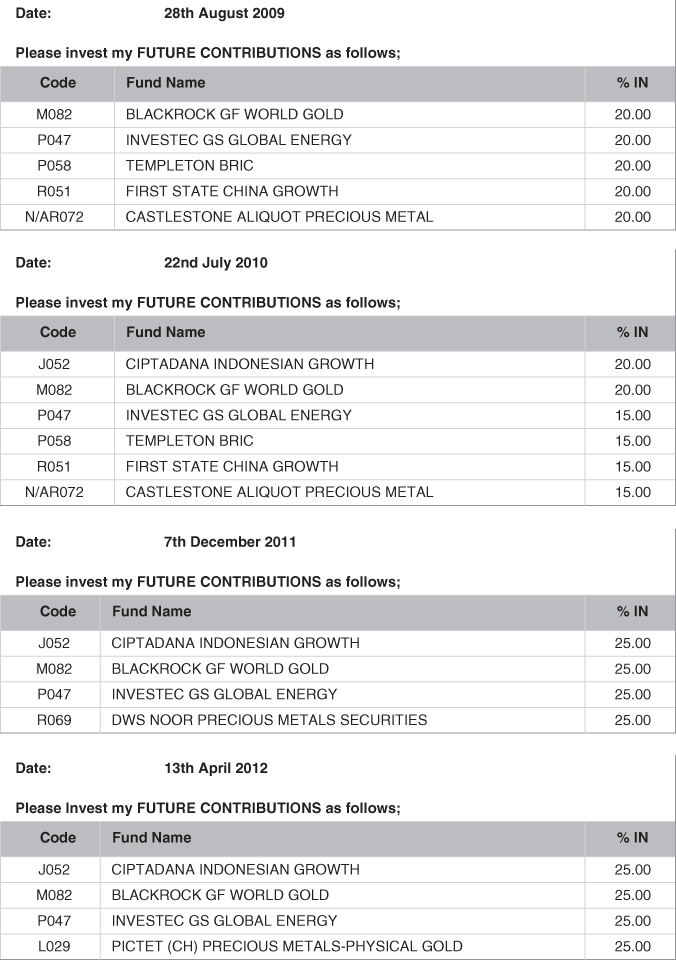

The portfolio was heavily concentrated in gold, other precious metals, and emerging stock markets, such as Brazil, China, India, and Indonesia. At no point, since Steve opened the account in 2007, was it globally diversified across a variety of international stock markets and bonds. Note the screen shots of his portfolio in Figure 4.2, taken in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012.

Figure 4.2 Irresponsible Investment Allocations

Steve's account was layered with unnecessary fees. What's more, without bonds and with no exposure to the world's biggest markets (US and European stocks), it was lopsided and risky.

Adding alcohol to a climber's water, his advisor significantly increased Steve's gold holdings in late 2011, just in time for gold's 28 percent price plunge. By April 2012, Steve had 50 percent of his portfolio in gold and precious metals. By October 2013, the advisor increased this percentage to 79 percent (not shown).

According to his account statement, Steve's investment value plummeted 20.68 percent between his 2007 account opening date and October 2013. What if, instead of concentrating too much on a specific asset class, Steve's portfolio were properly diversified? If that were the case, he wouldn't be plucking dirt from his wounds. With a blended portfolio, including a Canadian bond index, a Canadian stock index, and a global stock index, Steve's money would have grown 20 percent instead of dropping 20.68 percent (see Table 4.6).

Table 4.6 Undiversified Portfolio Gets Dragged through the Dirt

SOURCES: Steve Batchelor's account statement; portfoliovisualizer.com.

| September 30, 2007, to October 5, 2013 | Canadian Diversified Portfolio with iShares ETFs* |

| Steve's Undiversified Portfolio | 30% Canadian Stock Index (XIC) 25% US Index (XSP) 25% International index (XIN) 20% Canadian Bond Market Index XBB |

| –20.68% | +20% |

*NOTE: These were the iShares products available in 2007. These US and International ETFs are currency‐hedged. Non‐currency‐hedged ETFs are now available. Studies show non‐currency‐hedged stock market ETFs perform better, which is why my Canadian model portfolios include them.

How much would Steve's portfolio have to gain to break even after a 20.68 percent loss? An instinctive answer would be 20.68 percent. But the reality is heftier. It can take years for a portfolio to recover large losses (see Table 4.7).

Table 4.7 Gains Required to Offset Losses

| Portfolio Loss | Gain Required to Get Back to Even |

| –10% | +11.1% |

| –20% | +25.0% |

| –30% | +42.9% |

| –40% | +66.7% |

| –50% | +100.0% |

| –60% | +150.0% |

| –70% | +233.3% |

Steve's 20.68 percent drop would require a gain of 26.07 percent to break even. He underperformed a diversified portfolio of stock and bond indexes by more than 46 percent in just six years. The advisor, an offshore pension cowboy, cost the Canadian dearly.

Canadian Teacher Gets Scalped

Imagine treading water, miles from land. A lifeguard arrives in a giant rowboat. He says, “Hey, I can help.” He sticks a weight belt around your neck. He fastens it tightly with a padlock. “Now swim hard for shore,” he says.

This happened to Eric Smith…sort of.

In 2009, a financial salesperson walked into the British International School of Phuket, in Thailand, where Eric still works (I changed his name to protect his identity). The salesperson (I refuse to call him an advisor) signed dozens of teachers into an offshore investment scheme. If I could, I would tie a rope to this guy's ankles and hang him from a tree.

In 2017, I gave investment talks in 11 different countries. People often showed me their investment portfolios. Eric's advisor's LinkedIn profile says he's the director at SCI Employee Benefits. It should say he's a master at losing money. I spoke at numerous schools throughout Africa and Asia. This guy was a mosquito. Across multiple countries, he found a lot of naked campers.

You can see Eric's portfolio in Table 4.8. He started regular investments into these funds in 2008.

Table 4.8 SCI Group Ltd. Friends Provident Premier Plan

SOURCE: Screenshot of Friends Provident Premier portfolio.

| Fund | What's Inside This Fund? | Portfolio Allocation |

| P33 Aberdeen Global Chinese Equity | Chinese stocks and companies that do most of their business with China | 15% |

| R25 Invesco Asia Infrastructure | Asian stocks | 10% |

| J30 J.F. India | Indian stocks | 15% |

| J32 J.F. Pacific Securities | Asian stocks | 10% |

| P67 Mellon Global Bond | Global bonds | 10% |

| M82 Blackrock GF World Gold | Gold and other mining companies | 15% |

| R52 Schroder Middle East | Middle East stocks | 10% |

| JP Morgan ASEAN | Asian stocks | 15% |

Eric Smith is Canadian. But his portfolio has no exposure to Canadian stocks. The US stock market is the largest in the world. But Eric's portfolio has no exposure to US stocks. European stocks make up the next biggest market. But there's no exposure to European stocks.

In fact, about 90 percent of the world's stock market capitalization isn't represented in this portfolio at all. The portfolio is about as effective (and ethical) as a one‐legged guard dog.

Sadly, this isn't an isolated example. This salesperson chose the same pet funds for dozens (if not hundreds) of other investors around the world.

I reached out to HARO (Help A Reporter Out). It's an online source for reporters who are looking for quotes from experts. I wanted CFPs to weigh in on this portfolio. As CFPs, they've been trained (unlike most offshore investment sellers) to build diversified portfolios.

I showed them Eric Smith's portfolio. I then asked for their opinion. Of course, they didn't know Eric's age, his background, or his tolerance for risk. But in this case, those details didn't matter. If this portfolio were a picture, it would represent a toddler riding on the hood of a racing car. Evel Knievel, himself, wouldn't have done that to his kid.

Notice the consistency of the responses:

This is clearly not a reasonable investment allocation and this so‐called “advisor” is not likely to be a fiduciary. If the “advisor” is a fiduciary, they should likely be sued. There is no exposure to Canadian stocks, US stocks, or European stocks, despite the fact that those countries make up nearly the entire worldwide exposure to stocks based on market capitalization.

—Ben Westerman, CPA/PFS, CFP, HM Capital Management; Clayton, Missouri

I can't imagine why anyone would build a portfolio like this … unless of course the person who did build it was on the receiving end of significant commission payments. There are many lower cost, better diversified options than this available to the well advised expatriate investor.

—Stuart Ritchie, CFP, Chartered Wealth Manager, AES International; Dubai

This portfolio should be called The Concentrated Asian Contagion Combustible Portfolio or The What Goes Up Must Come Down Fund, or why not just “The Gut Wrencher Fund.” It isn't diversified at all!

—Kevin M. O'Brien, CFP, AIF, CAP; Peak Financial Services Inc.; Northborough, MA

I would not want a US‐centric client to have all of their money in large US stocks, so I would definitely not want to put a Canadian client solely in emerging markets. While I do love my clients having some emerging markets exposure, 100% is excessive.

—Jim Wright, Chief Investment Officer, Harvest Financial Partners; Paoli, PA

Proper portfolio modeling should be rooted in three primary drivers: diversification of non‐correlated asset classes, the investor's investment objective, and the investor's risk tolerance. This portfolio seems to fail on all fronts.

—Brent R. Sutherland, CFP, AIF; Ntellivest, Pittsburgh, PA

One of my biggest pet peeves is when people say investing in the stock market is no better than taking your savings to Vegas. In no way is that true, especially if you have a well‐built diversified portfolio. However, in this case, taking the money to Vegas might have been a better bet. There is no diversification in his portfolio. Every position is concentrated in one of the most riskiest asset class, emerging markets.

—Kevin Michels, CFP, Medicus Wealth Planning; Draper, UT

This investment salesperson did not consider the importance of a diversified portfolio and asset allocation. Also, this salesperson was probably exhibiting a market timing bias because in 2009 emerging market stocks were doing very well. He probably tried to “sell” the recent market performance of this sector.

—Ben Offit, CFP, Clear Path Advisory; Pikesville, MD

This is an amateur's mistake. This portfolio will likely underperform in the long run. Having exposure to both developed and emerging [markets] can lower the overall portfolio risk and bring steadier long term gains.

—Andrea Kennedy, CFP and Chief Investment Strategist, Wiser Wealth; Singapore

This portfolio is crazy! We can see it's heavily concentrated in Asia, the Middle East, and commodities with no exposure to the much larger (and more diversified) markets in North America and Europe. It only has exposure to about 25% of the global economy, in some of the most risky areas at that!

—David Dyck, CFP, WealthBar; Vancouver, BC, Canada

Dan Bortolotti is one of Canada's best‐known financial advisors. His detailed response explains the issue well:

All investors have some degree of “home bias,” which means they tend to own too many stocks from the region where they live or work. But Eric's portfolio looks like it was designed by an advisor who is unaware there's a world outside of Asia.

Countries such as China and India have huge populations and growing economies, but together they make up about 3.5 percent of the global stock market. The Middle Eastern stock market is a fraction of 1 percent. Concentrating your life savings in these tiny markets is extraordinarily risky. And that doesn't even account for the enormous currency risk Eric is taking: if Asian currencies lose value relative to the Canadian dollar this portfolio could be devastated, even if the stocks themselves remain stable.

There also seems to be a lot of redundancy in the holdings: several of the funds cover the same regions, so many stocks probably appear in more than one fund. This means the portfolio is even less well diversified than it first appears, which is saying something.

A more appropriate portfolio for Eric would include healthy exposure to North America and Europe. There are several global equity ETFs that could accomplish this with a single holding: the Vanguard FTSE Global All Cap ex Canada Index ETF holds more than 10,000 stocks in about 40 countries. Its annual fee is 0.27 percent. If Eric also added a Canadian stock market ETF, his portfolio would have full global representation.

It's also worth noting that only 10 percent of Eric's portfolio is in bonds, which seems very aggressive. Unless he has an iron stomach, Eric should consider a more balanced portfolio with perhaps 30 percent to 40 percent in bonds. And if he's planning to spend down his portfolio in Canada, those bonds should be denominated in Canadian dollars to eliminate currency risk.

—Dan Bortolotti, CFP, CIM, Associate Portfolio Manager, PWL Capital, Toronto

Why Would a So‐Called Professional Do This to Another Person?

There are two possible reasons:

The advisor has limited understanding of how the stock markets work.

Or

- He badly wanted the commission. He didn't care about Eric.

Let's look at the first possibility. There's a chance that the advisor simply didn't know better. He dug his hand into a cookie jar of funds. But he refused to add any vegetables to Eric Smith's plate. Friends Provident paid the advisor at SCI Group a nice sugar boost, in the form of a big commission. But Eric got the shaft.

Perhaps the advisor didn't know how to diversify Eric's money.

The Chinese stock market might have impressed him. It had gained 300 percent the previous two years. In fact, because four of Eric's funds contain some Chinese stocks, China is the most heavily weighted market in Eric's portfolio.

That's a pity. A stock market that produces Incredible Hulk–like growth during one time period usually follows up with extraordinary shrinkage.

Chinese stocks gained 300 percent in the two years prior to 2007. But after 2007, Chinese stocks fell hard. By May 2017, they hadn't fully recovered.

Much of Eric's portfolio is also invested in funds with other emerging‐market stocks. In Table 4.8, you can see Invesco Asia Infrastructure; J.F. India; Schroder Middle East; JP Morgan ASEAN.

Like the Chinese fund, they had shown some massive gains before Eric had started to buy. But they fell into a canyon shortly after that. By May 2017, emerging‐market stocks hadn't fully recovered from their previous mountain high.

Eric's advisor also put 15 percent of his portfolio in the M82 Blackrock GF World Gold fund. By now, you'll know why. Gold had averaged 30 percent annually over the previous the three years.

Gold prices peaked three years later. But it soon went on a painful slide.

Eric invested $600 a month to his portfolio starting February 2008. By April 30, 2017, his portfolio was worth less than what he had invested. Table 4.9 shows how badly it performed, compared to a global stock market index fund.

Table 4.9 Eric's Friends Provident Premier Portfolio versus Global Stock Market Index, February 2008 to April 2017

SOURCES: Friends Provident portfolio screenshot; Vanguard.com.

| Portfolio | Amount Invested* | April 2017 Value |

| Eric's SCI Group/Friends Provident Premier portfolio | $66,600 | $65,600 |

| Global Stock Market Index | $66,600 | $112,030 |

*Based on $600 a month.

Some people might say, “He didn't lose much.” I disagree. The markets rose considerably. Inflation eroded that money's buying power. And Eric still can't close this account without paying a penalty.

What's more, there's a large opportunity cost. If Eric had invested the same monthly proceeds into a global stock market index, he would have $112,030. That's $46,430 more. But that's just the tip of an iceberg.

Would You Let Your Children Lose $2 Million?

Every decision in life comes with an opportunity cost. It's a result of what we would have gained if we had made Decision A over Decision B. It's easy to measure when it comes to money. If Eric had invested in a global stock market index, he would have $46,430 more money than with the investment scheme he chose with SCI Group Ltd. That was the opportunity cost of Decision A over Decision B.

That money is gone forever. But for Eric's children, the opportunity cost exceeds far more than that.

Let's assume Eric invested $46,430 for his children's future. If the money earned an annual 8 percent return, it would be worth more than $2.17 million 50 years later. That's the potential long‐term cost of his advisor's greedy push.

We can blame some of the pain on the Friends Provident investment fees. Like Steve Batchelor, Eric paid annual charges of more than 4 percent per year. The money that Eric deposited during the first 18 months attracted fees that were higher than 9 percent per year.

But it was the salesman's crazy fund selections that stabbed it through the heart.

Was This Financial Advisor A Full‐Blown Psychopath?

Was the financial salesperson ignorant, psychopathic, or perhaps a Machiavellian?

Maria Konnikova, author of The Confidence Game, references psychology literature when she says, “‘Machiavellian’ has come to mean a specific set of traits that allows one to manipulate others to accomplish one's own objectives–almost a textbook definition of a con.”43

If the advisor were a psychopath or a Machiavellian, he might have tried to fool Eric to get a big commission. Showing charts of winning mutual funds might impress a conman's mark. The salesperson might have crooned, “This is the sort of jackpot that I can give you.”

Unfortunately, Eric lost money. The salesman at SCI Group had snagged him on a hook. If you want to look him up, the advisor's last name rhymes with crook.

Investor in Thailand Makes the Great Escape

Colette Hirst works at a small international school in northern Thailand. One day, the head of her school forwarded an e‐mail to his faculty. It was from a financial salesperson from Guardian Wealth Management. He asked, “How much is that cappuccino costing you every day; should you be saving for your future?”

Colette met the salesperson at school. She says, “He did a full report, a risk questionnaire and he came back with this plan. I agreed to pay £950 from my Thai credit card every month [£11,400 a year] and they add a bonus up to around £1,100, I think.”

She invested with Guardian Wealth Management. The salesperson signed her up for a RL 360 Quantum plan in March 2017. One month later, the statement read, “The policy value is up 75.13% as a percentage of premiums invested.”

“I thought that was great,” says Colette.

But her investment hadn't actually increased by 75.13 percent. It was the result of a signing bonus. RL 360 calls it an “Extra Allocation” bonus.

Here's how the prospectus explains it:

If you invest at least USD850 (or currency equivalent) per month, we will increase your premium allocation rate by 1%, adding bonus units to your policy. 44

Colette is entitled to a 1 percent bonus on each deposit, every time she adds money. But to make a big, visual impact, the company adds the bonus right away. That's why Colette's statement says she added £1,900, but the investment statement says that after just two months, her portfolio is worth £3,327.40. So far, that sounds pretty cool.

The firm also offers a loyalty bonus if Colette keeps investing until 2029. The RL 360 Quantum prospectus reads, “For each year that you pay your premiums, we will add a bonus of 0.25% of the final regular fund value to your policy.”

That means, if she invests for 12 years, she would get a bonus of 3 percent at the end of the 12‐year term. If her portfolio were worth £100,000, that bonus would boost it to £103,000.

What's not to like?

Unfortunately, the salesperson didn't reveal everything. He didn't explain the investment's annual charges.

The prospectus states:

Initial unit charge: A charge of 0.50% per month [6.0 percent per year] will be deducted from the value of the initial units held within your policy.

It also describes a contract charge:

There is an ongoing contract charge of 0.125% of the current fund value, deducted each month in arrears [1.5 percent per year]. The charge is applied proportionately across both initial and accumulation units.

The prospectus also says there are annual fund charges:

The funds that are held within your policy will be subject to an annual management charge. The charge will vary per fund chosen.

The fund charges run about 2 percent per year.

If Colette had continued to add money, the money that she would have added over the first 18 months would have incurred charges of 9.5 percent per year over the 12‐year duration of her investment term. That includes the initial unit charges (6.0 percent per year); the contract charges (1.5 percent per year) and the annual fund charges (2 percent per year).

Colette signed up to deposit £950 a month. That's £17,100 deposited (over the 18‐month period) costing 9.5 percent per year. As it states in the company's prospectus: “This charge will be deducted in arrears throughout the premium term.” In other words, she would pay 9.5 percent charges on this initial £17,100 over the duration of the 12‐year term.

But What About the Bonus?

Let's not forget the initial bonus of £1,100.

Does she get to keep it? Yes and no.

Fees would erode much of that £17,100 of deposits, plus the £1,100 initial bonus, over the 12‐year term.

Assume it were worth £18,200 (£17,100 in contributions plus the £1,100 bonus) with 10.5 years left on the 12‐year policy. That isn't likely because it would have attracted fees of 9.5 percent per year. But let's be sporting.

Now assume Colette's fund averaged a compound annual return of 7 percent before fees. In such a case, the money that entered her account (including the bonus) would lose 2.5 percent per year (7% return minus 9.5% in fees) for the duration of the 12‐year term.

After 10.5 years, that money would lose £4,249. This exceeds the initial bonus of £1,100 that RL 360 gave Colette when she started her account.

So the initial 18 months of contributions would be worth £13,951 at the end of the 12‐year term because it would have lost money.

Money added after the initial 18‐month period would attract annual fees of 3.5 percent per year (including fund costs and contract charges). If Colette's fund averaged a compound annual return of 7 percent per year—before fund management fees and RL 360s fees—she would net a compound annual return of 3.5 percent over that 10.5‐year period.

Over the remaining 10.5 years, this would add £146,668 to Colette's £13,951 (which was the assumed end value of her initial units).

In total, her portfolio would be worth £160,619 after 12 years (£13,951 + £146,668). That's before the 3 percent loyalty bonus. After the bonus, she would have £165,437.

Smoke and Mirrors Pushed Aside

Because Colette would have added £950 a month (£11,400 a year) that would equate to an average compound return of 2.9 percent per year. That includes all bonuses. But it doesn't include the “investment policy fee” of £60 a year (£5 a month), which the company says “will increase every year in line with the Isle of Man Retail Price Index.”

If, over the same 12‐year period, a combined portfolio of global stock and bond market index funds averaged a compound annual return of 7 percent per year, before fees, Colette would earn about 6.8 percent per year after fees.

That's a lot higher than 2.9 percent.

There were also two other things that Colette wasn't told. Two months after her first payment, she got around to asking the salesperson a couple of questions that she should have asked before: “If I want to sell the entire investment to cover an emergency or if I want to buy a house, would I have full access to that money? Could I simply sell it all?”

The salesperson said, “No.”

You Can't Sell This If You Want to Buy a House

According to the policy's prospectus, if an investor tries to sell everything within the first 18 months, they will lose everything.

If you surrender your policy whilst your original premium is still within its initial allocation period, your policy will have no surrender value—in effectively suffering a 100% surrender charge.

If an investor tries to sell everything with 10 years left on the policy, they will lose 56.5 percent of the total portfolio value. With 9 years left on the plan, they would lose 52.5 percent. If an investor tries to sell everything with one year left on the policy, they lose 8.0 percent of the total portfolio value.

“I decided to cancel the investment plan after just two months,” says Colette. I lost what I had deposited, of course, but I felt lucky to escape. I've since started to invest in a diversified portfolio of low‐cost index funds.”45

Poor Performance Packs a Three‐Way Punch

Stock markets rise. Stock markets fall. But anyone investing money over a long time period should make decent profits if the fees are low and the money is diversified. After all, stock markets rise, on average, two out of every three years. Stocks regularly hit new highs.

I turned 47 years old in 2017. Over my lifetime, the S&P 500 (with dividends reinvested) hit all‐time highs during 31 different calendar years. Stock market investments grow. That's what they do.

But if we invest in an expensive offshore pension, it's tough to make money. If a fool, psychopath, or Machiavellian builds your investment portfolio, you'll really be forced to suffer.

Unfortunately, poor investment performance can have a knock‐on effect.

In October 2016, I met a woman in Switzerland named Soukeina. She used to work in Tunisia, where an “investment guy” sold her an Aviva investment scheme.

Between January 2008 and September 2016, Soukeina added money every month. By October 2016, her contributions had totaled $39,951. But after adding money for almost 10 years her portfolio was worth just $29,006. Globally, most of the world's markets have risen a lot since 2008. According to portfoliovisualizer.com, if Soukeina had invested her monthly contributions in a global stock index fund, it would have grown to $56,962.