Chapter 19

Setting Your Bull's‐Eye

I recently had dinner with a financial advisor in Qatar. Over a delicious spinach salad, the advisor told me that one of his clients earns £450,000 a year. Over the previous decade, his total salary earnings had exceeded £3 million.

As a British expat in Qatar, the lawyer doesn't pay income tax. His employer pays for his housing costs and provides him with a car to use.

“Unfortunately,” said the advisor, “unless my client makes some drastic changes, he'll never be able to retire.” I almost choked on a crouton. “How is that possible?” I asked. But I already knew the answer. He spends almost every penny he makes. His investment portfolio was valued at just US$20,000.

It's tough to know who's wealthy and who's living a fantasy. Plenty of high‐salaried expats are metaphorically flying over the ocean in private jets with near‐empty fuel tanks. Their salaries might exceed a million dollars a year or more. They might drive Ferraris. They might own homes in Spain and France (with eye‐watering mortgages). They might travel first class. But many aren't much different than professional football players.

Sports Illustrated estimates that 80 percent of professional (NFL) football players go broke within three years of their retirement. Their average salaries exceed $2 million a year. But when their salaries dry up, they end up broke.1

Such boneheaded blunders aren't just reserved for professional athletes. Plenty of expats suffer too. Sam Instone says it's more common than we think. “I see this all the time,” says the CEO of AES International. “I've met plenty of professionals who earn millions of dollars a year. They live luxurious lives. But many of them are swimming in debt or they spend almost everything they have. So many of these people can be brilliant in one capacity of their lives, but completely clueless when it comes to planning for their futures.”

The late Thomas J. Stanley studied wealthy Americans for most of his career. The former university professor and marketing researcher co‐wrote The Millionaire Next Door (Gallery Books, 1998; Taylor Trade Publishing, 2010) with William D. Danko. Stanley also wrote The Millionaire Mind (Andrews McMeel, 2001) and and Stop Acting Rich (Wiley, 2009, 2011). He blew the top off our perception of what it means to be wealthy.

While researching American millionaires, Dr. Stanley revealed the following in his aforementioned books.

Some wealthy people drive high‐end, expensive cars. But most rich people prefer Fords and Toyotas. Most of the high‐end sports cars that you see on the road are not driven by millionaires. Instead, most of them are driven by high‐salaried people with big debts.

Some wealthy people live in million‐dollar homes. But most millionaires live in homes that are worth less than a million dollars. Stanley revealed that most homes valued above a million dollars aren't owned by millionaires. Once again, they're usually owned by high‐salaried people who owe a lot of money.

When my wife and I get invited to a wealthy person's home for dinner, she often worries about what kind of wine to bring. “I know they're really rich,” she will say, “so I want to make sure we bring something worthy.” Over time, however, she is learning that wealthy people usually prefer the same drinks as middle‐class wage earners. Thomas Stanley's research found the same thing.

In Stop Acting Rich, Dr. Stanley revealed statistics on people who collect and drink expensive wines. As with most people who drive flashy cars and live in million‐dollar homes, most wine snobs aren't millionaires. More often, they're just high‐salaried people with very expensive tastes.

What's a Better Definition of Wealth?

Many people define a person's wealth by their salary, what they wear, or what they own. But if a person can't live indefinitely without a paycheck, they aren't wealthy at all. I define wealth differently. In my view, if a person can survive without a paycheck, and if their investments can generate more than twice the median household income in that person's home country, then that person is wealthy.

For example, the median household income in the United States was $56,516 per year in 2015.2 If a person's investments can indefinitely generate at least two times that amount each year (that's $113,032), then I would say they are wealthy. In contrast, if an American expatriate, for example, earns $5 million per year and if she has a net worth of $1 million, she might be in trouble. Her net worth would only be one‐fifth her annual salary. She might be addicted to a lifestyle of consumption. I call that a high burn rate. Such people suffer from expatitis.

What's This Ailment Expatitis?

Expatitis isn't a common medical term. But if you're an expatriate, chances are either you or someone you know is infected. It's easily diagnosed, even among international schoolteachers. Symptoms get posted on Facebook. Fortunately, it doesn't hurt—at least not in its early stages.

Unlike bronchitis, arthritis, appendicitis, or colitis, expatitis is rather pleasant. Afflicted individuals get addicted to five‐star holidays, manicures, pedicures, massages, expensive dining, and entertainment. But expatitis creates delusions. It's much like drinking champagne underwater without checking your air supply.

Symptoms creep up. The better the expat's financial package, the greater the risk of contracting the condition.

I've been giving financial seminars to expatriates for more than a decade. When I ask people to estimate their retirement expenses, their needs vary. And I expect that. But here's the irony. Those reporting they need the most money are usually saving the least. They're like 500‐pound men saying, “I want to run a marathon in less than 3 hours.”

Fortunately, such delusion has a savior.

Whether you're suffering from expatitis or hoping for a more luxurious retirement than you could afford in your home country, retiring overseas offers a creative solution. You won't need as much money if you retire where it's cheap.

Cheating Conventional Retirement Rules

Meet Billy and Akaisha Kaderli. They live better than the typical American retiree. But they also spend less.

If you struck up a midweek conversation with them, you might peg them as early retirees. The energetic 64‐year‐olds share the glow of a couple freed from the rat race. But a few things make them different. They spend long‐term stints (sometimes years) in low‐cost countries. They also retired when they were just 38 and will mark their 28th year of retirement in 2019.

Previously, they owned a restaurant in the United States. Akaisha ran it. Billy worked at an investment firm. But in 1991, they quit. While most of their friends were acquiring larger houses, new cars, and filling their homes with fine furnishings, the Kaderlis downsized. “We sold most of our possessions,” says Akaisha, “including our house and our car.” For a quarter of a century, they've lived off their investment portfolio. Today, it's worth more than it was the day they retired.

To stretch their income, they moved to Lake Chapala, Mexico. But they enjoy bouncing around, renting homes in new locations for months at a time. Some of their favorite hubs include Thailand and Guatemala. They commit to community projects, meeting people, embracing different cultures, and learning different languages. They have a mortgage‐free apartment in the United States, where they stay when they visit family.

The Kaderlis also discovered how to bask in luxury on a shoestring. Through TrustedHousesitters.com, they found a luxurious home overlooking Lake Chapala in 2013. They stayed four months without paying rent. “We may do more of that in the future,” says Akaisha, “if the right opportunity arises.”

Their living costs might be low, but the Kaderlis don't scrimp. In 2017, Akaisha said, “Into our 26th year of financial independence our spending has remained around $30,000 per year or less, mostly less. Living in low‐cost, culturally rich, high‐lifestyle countries such as Thailand, Vietnam, Mexico, and Guatemala, we utilize medical tourism to keep expenses low and quality of care high. The above figure includes housing, transport and airfare, food, entertainment, and medical.”3

The Kaderlis are the authors of The Adventurer's Guide to Early Retirement (CD‐ROM, 2005). They also maintain a helpful blog, Retire Early Lifestyle, at www.retireearlylifestyle.com, where they share their stories and tips for living well on less.

Suzan Haskins and Dan Prescher, authors of The International Living Guide to Retiring Overseas on a Budget (John Wiley & Sons, 2014), live much like the Kaderlis. Located in a small town in Ecuador, they spend roughly $25,000 a year. “We live well…. We go out to lunch and dinner once a week … we enjoy the occasional martini or scotch, and every evening with dinner we polish off a bottle of wine.” Their costs include at least one annual trip to the United States, occasional fine dining, and a worldwide health care policy that costs roughly $5,800 a year, with a $5,000 deductible.4

Married Couple Lives Well on Just $20,000 a Year

In late 2014, my wife and I spent three months in Lake Chapala, Mexico. It's a popular mecca for North American retirees.

It's situated in the mountains—about 5,000 feet above sea level—so it never gets too hot. Temperatures are pleasant all year round. It's safe and culturally colorful. That's where we met Jim and Carole Cook. They have lived in the lakeside town of Ajijic for about 10 years. “We spend about $1,600 a month down here,” said Jim.

My wife and I had lunch with the Cooks at one of the town's most popular restaurants. The total bill for four was US$16.32. That evening, my wife and I had dinner in the neighboring town of Chapala. Six potato and cheese zopes cost just $4.

Two‐bedroom houses in Chapala rent for as little as $300 a month. In Ajijic, where rental prices are higher, you can get a spacious home on the hill with a lake view, a swimming pool, a gardener, and someone to maintain the pool for $800 a month.

I asked Lisa Jorgensen why she moved from Massachusetts to retire beside Lake Chapala. “I was bored,” she said. “I needed adventure. And I was broke.”

When we had coffee together, she was renting a villa in Ajijic for $700 a month. Her home had three fireplaces, a swimming pool, and a beautiful garden. “All garden maintenance, including the pool's, is covered by the rent,” she said.

Helpful resources for potential expats include Judy King's popular book, Living at Lake Chapala,5 and The Adventurer's Guide to Chapala Living, by Billy and Akaisha Kaderli.6

But what about medical? Sixty‐four year old Mark Boyer lives in a house he bought, overlooking Lake Chapala in the colorful town of San Antonio. He and his wife, Marianne, live about one mile from Ajijic. Traveling to the United States for medical procedures doesn't appeal to him because of its distance and cost. Like many of the region's expats, he and his wife say they pay for private medical insurance. When we chatted in 2014, they paid a combined total of $2,200 per year with IMG International Medical Group.7

Global health insurance companies set rates based on your country of residence. Mexican health care costs are low, so the premiums are as well. After researching hospitals, Boyer says, “Three of the hospitals in Guadalajara [a one‐hour drive from Lake Chapala] are as good or better than about 85 percent of the hospitals in the United States.”

Mark and Marianne carried a $5,000 deductible each. Like most of the region's expats, they pay out of pocket for doctor's visits. US‐educated doctors charge about $15 a visit in the Lake Chapala region.

The couple never suffered from expatitis. But their retirement location is well suited to expats who spent a career living beyond their means.

Could You Retire on Less than $15,000 a Year?

Bill Taylor is an expat with a real estate office in Mexico's Puerto Vallarta Marina. He lists the cost of living for couples who live at the Royal Pacific Yacht Club condominium development. In 2017, he listed average annual costs at just $13,311 a year (residents own their own condos). His newsletter lists and answers plenty of questions about costs of living and health care.8

International Living magazine voted Mexico the world's top international retirement destination for 2017. But plenty of other low‐cost countries also exist. The magazine compares factors such as health care, cost of living, and how easy it is to fit in socially. Table 19.1 shows their country rankings for 2017.9 They gave a score for each factor, as well as an overall grade at the end. According to International Living, the higher the score, the more desirable the location.

Table 19.1 International Living's Annual Global Retirement Index—Final Scores

SOURCE: International Living magazine: https://internationalliving.com/the‐best‐places‐to‐retire/.

| Country | Buying & Renting | Benefits and Discounts | Visas and Residence | Cost of Living | Fitting In | Entertainment and Amenities | Health Care | Healthy Lifestyle | Infrastructure | Climate | Final Scores |

| Mexico | 94 | 88 | 91 | 89 | 91 | 97 | 91 | 88 | 90 | 90 | 90.9 |

| Panama | 87 | 100 | 96 | 82 | 90 | 93 | 89 | 93 | 89 | 89 | 90.8 |

| Ecuador | 97 | 99 | 82 | 83 | 89 | 89 | 87 | 92 | 89 | 100 | 90.7 |

| Costa Rica | 89 | 78 | 85 | 80 | 90 | 93 | 96 | 97 | 87 | 84 | 87.9 |

| Colombia | 89 | 66 | 79 | 93 | 85 | 94 | 94 | 95 | 91 | 91 | 87.7 |

| Malaysia | 89 | 70 | 85 | 87 | 93 | 95 | 97 | 92 | 89 | 73 | 87.0 |

| Spain | 85 | 71 | 70 | 78 | 88 | 90 | 89 | 90 | 98 | 89 | 84.8 |

| Nicaragua | 97 | 69 | 72 | 97 | 84 | 85 | 80 | 97 | 73 | 82 | 83.6 |

| Portugal | 84 | 72 | 76 | 82 | 85 | 80 | 84 | 90 | 95 | 83 | 83.1 |

| Malta | 79 | 71 | 76 | 77 | 92 | 85 | 85 | 79 | 90 | 83 | 81.7 |

| Honduras (Roatán) | 78 | 73 | 87 | 73 | 96 | 76 | 84 | 74 | 88 | 81 | 81.0 |

| Thailand | 84 | 67 | 61 | 85 | 88 | 90 | 89 | 80 | 83 | 83 | 81.0 |

| Italy | 67 | 74 | 74 | 79 | 78 | 90 | 81 | 85 | 93 | 84 | 80.5 |

| Peru | 86 | 60 | 80 | 94 | 86 | 74 | 83 | 72 | 80 | 87 | 80.2 |

| Belize | 77 | 81 | 84 | 72 | 95 | 74 | 86 | 85 | 70 | 78 | 80.2 |

| France | 65 | 79 | 74 | 54 | 87 | 96 | 88 | 79 | 93 | 82 | 80.0 |

| Cambodia | 76 | 57 | 77 | 99 | 89 | 91 | 80 | 83 | 69 | 79 | 79.5 |

| Bolivia | 93 | 62 | 64 | 87 | 80 | 76 | 72 | 83 | 84 | 88 | 78.9 |

| Philippines | 60 | 72 | 64 | 85 | 95 | 90 | 89 | 73 | 84 | 70 | 78.2 |

| Dominican Republic | 91 | 70 | 60 | 81 | 85 | 85 | 82 | 77 | 82 | 68 | 78.1 |

| Ireland | 78 | 75 | 73 | 64 | 98 | 84 | 73 | 72 | 95 | 67 | 77.9 |

| Guatemala | 83 | 63 | 73 | 90 | 81 | 78 | 76 | 68 | 77 | 86 | 77.5 |

| Uruguay | 68 | 62 | 62 | 59 | 83 | 98 | 89 | 73 | 91 | 81 | 76.6 |

| Vietnam | 75 | 61 | 67 | 91 | 72 | 68 | 78 | 75 | 67 | 79 | 73.3 |

The Home‐Country Retirement Plan

Plenty of retirees choose to retire in their country of origin. Many of them wonder, “How much will it cost?”

Using 2017 data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Motley Fool writer Brian Stoffel says the average American retired household spends about US$44,600 per year.10 It's worth noting that the average American retiree spends a lot more than the typical Canadian, Australian, or British retiree. One reason could be the higher wealth disparity in the United States. This figure (US$44,600 per year) isn't a median. It's an average.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) Wealth Distribution Database, wealth disparity among Americans runs far higher than in any other industrialized country. As a result, wealthy retired couples push this average higher.11

Cost‐conscious American expats who choose to repatriate in the United States could seek high‐value cities. In 2014, CBS News listed 10 of the most affordable US cities in which to retire. They included cities “that many retirees might find desirable, including a mix of urban and rural attractions, good weather, easy access to amenities, and quality health care options.”12

They measured affordability based on the average tax burden, the low cost of living, and the median listed home price. I updated their Zillow Home Value Index to list respective regional home prices to 2017.13 The median listed home in the United States is priced at about $235,000. The typical home prices listed in Table 19.2 are $50,000 cheaper.

Table 19.2 Ten Affordable US Cities for Retirement

SOURCES: The Tax Foundation, www.cbsnews.com/media/10‐most‐affordable‐us‐cities‐to‐retire/, Zillow.com.

| City | Tax Burden* | Cost of Living Below the National Average** | Median Listed Home Price** |

| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | 10.2% | 12.8% below | $166,500 |

| Indianapolis, Indiana | 9.6% | 12.8% below | $119,900 |

| Omaha, Nebraska | 9.7% | 11.7% below | $195,000 |

| Decatur, Alabama | 8.2% | 10.8% below | $119,900 |

| Tulsa, Oklahoma | 8.7% | 11.6% below | $155,000 |

| Tampa, Florida | 9.3% | 7.6% below | $249,900 |

| Clarksville, Tennessee | 7.7% | 7% below | $169,900 |

| Corpus Christi/Rockport, Texas | 7.9% | 4.9% below | Corpus Christi: $199,900 Rockport: $279,500 |

| Alexandria, Louisiana | 7.8% | 4.9% below | $175,250 |

| Aiken, South Carolina | 8.4% | 6.8% below | $197,400 |

* Tax burden: % of taxpayer's income that goes to state and local taxes.

** Cost of living: US Consensus Bureau.

*** House values: Zillow Home Value Index, updated to included median listed home prices, February 2017.

Home prices will increase over time. By the time you retire, these cities might no longer be cheap. But looking up typical costs of living in your home country is worth doing before you repatriate. Some desirable places cost surprisingly little.

Of course, retirement costs differ from city to city, regardless of what country you plan to retire in. I use the site at www.numbeo.com to make cost‐of‐living comparisons.

That said, reported median and average retirement costs mean little because so much depends on you: your lifestyle, the city you want to live in, your financial resources, whether you'll be renting, or whether you'll be mortgage free. But if you want to see how much retired households spend in a few other countries, here are some examples.

In 2015, MoneySense magazine reported that the average Canadian retired household spends C$28,800 per year. They used data from the BMO Wealth Management Study.14

According to 2017 data provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), The Motley Fool's Edward Sheldon says the average British retired household spends £21,770 a year.15

In 2016, the Australian Centre for Financial Studies reports spending levels for retirees in 2016. Using data from 2014, they say the median single retired person spends about $18,000 a year. Retired couples spend $33,000 a year.16

How Much Money Will You Need?

If you're not financially free today, set a target.

Begin with the following question:

If you were retired today, how much do you think you would spend each year?

For now, ignore inflation. Everything from a back wax to cornflakes will cost more in the future. But we'll make adjustments for that later. Just consider how much you would need annually if you retired today. It's silly to suggest a specific number of dollars needed by every retiree. If you're retiring in London, England, for example, costs will be higher than in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Big spenders also require more. Five‐star holiday junkies have pricier tastes than those who reserve luxury for special occasions. Some experts suggest you should budget retirement expenses totaling 70 to 80 percent of your working household income. But such cookie‐cutter solutions make little sense. Even among those in the same income bracket, some people consume like gas‐guzzling Mack trucks; others sip like a Smart car. Your future expenses depend on your personal needs, wants, and chosen retirement location.

To estimate future costs of living, figure out what you're spending right now. Record every penny you spend for at least six months. It's easy to do with an app on your phone, or with a pencil and notebook. Then make adjustments for predicted retirement lifestyle changes. Without a job, you won't be maintaining a professional wardrobe. Nor will you be saving for your kids' college or your retirement. Do you plan to be somewhere cheaper or more expensive than where you currently live? In either case, make adjustments. Costs of living in the world's major cities are available at www.numbeo.com.

British Teacher in Japan Aims to Retire in Style

Kevin and Sachiko Elliott didn't begin their careers on a path to prosperity. Kevin, who's originally from Stratford‐upon‐Avon, in Warwickshire, England, says his parents didn't inspire him to think about building wealth.

The 42‐year‐old teacher, who now lives in Japan, says, “My parents divorced when I was very young. I remember being told, ‘We can't afford this or that.’” Sometimes, they pointed at material things and said, “Those are for rich people.”

Kevin accepted what they said.

He eventually moved to Japan to teach English. That's where he met his wife, Sachiko. “I was young and debt free,” he said. I decided to buy every gadget I wanted.”

After working hard for three years, reality set in. He was married. He and Sachiko were expecting their first child. But they didn't have any money. It was time to get serious. They bought a franchise English school and cut back on their personal spending. Kevin still worked full‐time as an English teacher. After 18 months, they sold their school, earning a 300 percent profit.

Kevin knew that he wasn't contributing to a defined benefit pension plan. Many of his friends will receive income for life after teaching their careers in England.

The British government won't be as kind to Kevin. He and Sachiko realize they'll have to build their own retirement income. That's why the couple continues to acquire investment properties. They rent them out for income.

“Over the past 10 years, I have purchased seven properties in Japan and one property back in England. I continue to work full‐time and we now have three wonderful children.” Kevin hopes to retire when he's 50 years old. But he knows that he'll have to continue to manage his property portfolio.

Over the next decade, he should be able to increase his tenants' rents to keep pace with inflation. That's a good thing. Inflation can be greedy. Inflation.eu compiles country inflation figures. In 1981, Canada's inflation rate recorded 12.12 percent; in 1975, Great Britain's peaked at 24.89 percent; and in 1979, the cost of living in the United States rose 13.29 percent.

Lately, inflation's appetitite has slowed. The decade ending 2016 saw Canada's annual inflation average just 1.61 percent; Great Britain recorded 2.30 percent; the United States recorded 1.72 percent per year.

But past decade levels are rarely repeated in the future. Caution is prudent. In this case, let's assume inflation will average 3.5 percent each year, which is slightly higher than the developed world's 100‐year average.

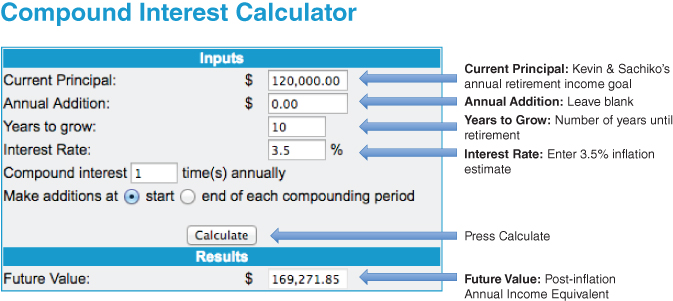

Kevin and Sachiko have decided to shoot for a retirement income of $120,000 a year (in 2018 dollars). If inflation averages 3.5 percent annually over the next 10 years, they would require an annual income of $169,271 in 2028. Their money would come from rental income and from a portfolio of index funds.

That would give the couple the equivalent buying power of $120,000 in 2018. In other words, if $120,000 can buy a certain number of goods and services now, it would require $169,271 to purchase those same goods and services in 10 years.

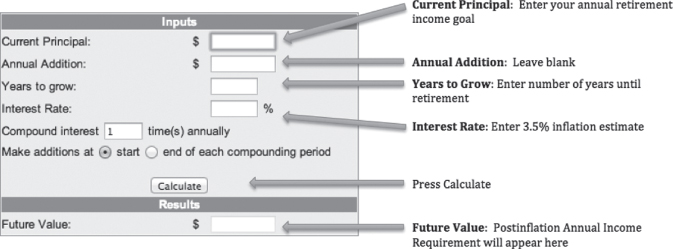

To make the postinflation adjustment, Kevin went to www.moneychimp.com and clicked on the compound interest calculator. Figure 19.1 shows how he used the website to estimate his postinflation income equivalency.

Figure 19.1 Kevin and Sachiko's Postinflation Adjustment

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Single Canadian Woman Lights Her Investment Fire

“I plan to retire when I'm 53 years old,” says Heather Pollock. “OK, it's a bit of a random number. But I chose it to light a fire under my butt!”

The 38‐year‐old Canadian lives in Dubai. It isn't a cheap place to live. That's why the teacher‐turned‐education‐consultant wants to work (and retire) where the costs of living are lower. “If all goes according to plan,” she says, “my business will allow me to be location independent. Hopefully, I'll feel like I'm semi‐retired long before I'm fully retired.” In preparation, Heather started to downsize last year. She moved to a smaller flat in Dubai. She also began to sell much of her furniture and belongings. “I want to live a more minimalistic lifestyle,” she says.

Heather plans to retire in a low‐cost beach community—perhaps in Malaysia, Bali, or Central or South America. She doesn't like Canadian winters. That's one of the reasons she did her teacher training in Australia, after a stint of traveling.

After she earned her teaching degree, Heather spent a cold winter searching for a job in Canada. One of her friends convinced her to move to South Korea. “I signed a two‐year contract at a school in South Korea,” she says. The school didn't pay a lot. But Heather didn't have to pay for her accommodation, so she saved half of every paycheck. Excited about the savings potential, she says, “I knew there was something to this international teaching gig!”

She then moved to the United Arab Emirates in 2010, where she took a job at an Australian international school. “I stayed for three years, completed my contract, and got the opportunity to work for an educational publisher in Dubai.”

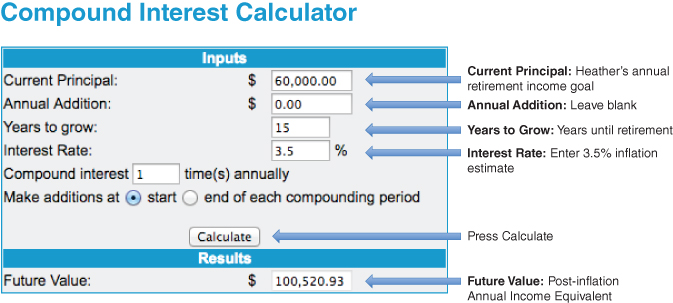

Heather doesn't think she needs retirement income exceeding C$30,000 to C$40,000 per year. That kind of income would serve her well in some of her favorite low‐cost beach haunts. But she has decided to shoot for an annual income of C$60,000 to provide a lot more wiggle room.

If the 38‐year‐old plans to retire when she's 53 years old, she'll have 15 years to build a portfolio that's large enough to provide such income. If inflation averages 3.5 percent annually over the next 15 years, Heather will require income of $100,320 per year. That's how much annual retirement income she would need, 15 years from now, to provide her with the equivalent buying power of $60,000 today. If she settles, instead, on a retirement income of $35,000 per year (in today's dollars) she'll require an annual income of $58,637 when she's 53 years old to provide the same buying power as $35,000 today.

Figures 19.2 and 19.3 show both scenarios, using the compound interest calculator at www.moneychimp.com.

Figure 19.2 Equivalent Buying Power of $60,000 if Inflation Averages 3.5 Percent

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Figure 19.3 Equivalent Buying Power of $35,000 if Inflation Averages 3.5 Percent

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Dubai‐Based Pilot Plans to See His Savings Soar

Allan Jones is originally from South Africa. He and his wife, Jane, have lived in Dubai for 11 years (I have changed their names and some of the details to protect their identity). As an airline pilot, Allan felt that living abroad would provide better financial opportunities.

They own two residential rental properties in Johannesburg, South Africa. Unfortunately, they fell victim to an offshore pension seller in Dubai. He promised them high returns. But he invested their money in a high‐cost product. As a result, the couple knows that their portfolio has some catching up to do.

“I would like to retire in about 10 years,” says Allan. “But because my investments have lost a lot of ground, we're going to have to save a lot more money over the next 10 years to reach our financial goal.”

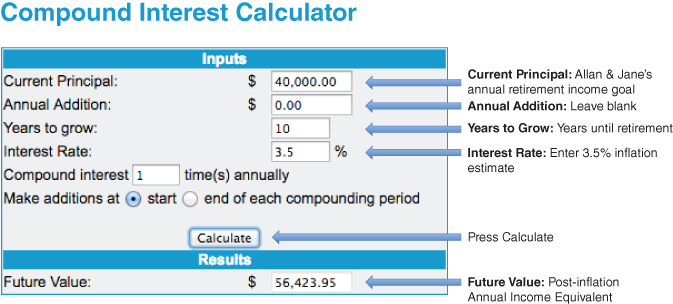

Allan and Jane believe that they'll require about $40,000 (US dollar equivalent) to retire in South Africa. One of their South African homes is already paid off, so they won't need to pay rent.

If inflation averages 3.5 percent per year (that's close to the 100‐year average for developed‐world economies), the couple would require annual income of $56,423. That sum would provide them with the equivalent buying power that $40,000 would provide them with today.

Figure 19.4 shows how they made such a calculation using moneychimp.com.

Figure 19.4 Equivalent Buying Power of $40,000 if Inflation Averages 3.5 Percent

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Now It's Your Turn

The first step toward planning your retirement is realizing what you spend today. My wife and I track every penny we spend on an app with our iPhone. I believe it's something everyone needs to do.

After all, every healthy business does it. Those not doing so head for bankruptcy. Government assistance doesn't intervene to save the grocery store or restaurant with the unbalanced budget. But many expatriates come to expect just that. Unfortunately, no such crutch exists for social pension noncontributors. Many expatriates sink or swim based on their own strokes.

After figuring out what you spend each year, deduct work‐related expenses. If you have children, deduct an estimate of what you spend on them each year. When you're retired, you'll no longer be saving for your children's college tuition, nor will you be putting part of your income aside for retirement. Use numbeo.com to determine whether your future retirement destination will cost more or less than where you currently live.

Next, determine how many years from now you want financial freedom. Estimate your postinflation cost of living with the compound interest calculator at www.moneychimp.com. Retirement is a journey to a foreign city. You've never been there, so you'll need a map—and knowledge of the steps ahead.

Take the first step now. Plug your numbers into Figure 19.5.

Figure 19.5 Your Postinflation Adjustment

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com.