Chapter 20

How Much Money Should You Be Saving?

Whether you expect to retire on $25,000 or $125,000 per year, you'll need a way to generate that income. Some will earn money from real estate rentals; others will rely on the stock and bond markets. Many will depend on both. Retirees may also receive some kind of pensionable benefit to augment their investment income.

Rental real estate is a great inflation fighter. If a retiree collects enough rental revenue to cover life's expenses today, it won't be undermined by the rising cost of living. Over time, rental income and inflation ride the same chair lift.

Those paying off investment mortgages before retirement can reap much from the rental proceeds.

Stock and bond market investments work a bit differently. If a retiree has a $500,000 investment portfolio, she'll need to know how much of her portfolio she can afford to sell each year. Those selling too much could end up broke—especially if they live longer than expected.

World Health Organization director Ties Boerma suggests a typical 60‐year‐old in a high‐income country could expect to live to 84. But you could live even longer—perhaps much longer.1

Costs of living also increase. So what percentage of your retirement portfolio can you afford to sell each year, to provide high odds you'll never run out of money?

How to Never Run Out of Money

Respected financial planner and researcher Bill Bengen suggests that retirees should be able to sell roughly 4 percent of their investment portfolio each year. He back‐tested a variety of historical scenarios, reporting results in a 1994 Journal of Financial Planning issue.2

As such, 4 percent of $500,000 would be $20,000; 4 percent of a million dollars would be $40,000. If you retired today with one million dollars, you could withdraw $40,000 in the first year of retirement. In the second year, you could sell a bit more to cover rising costs of living. The 4 percent withdrawal rate considers inflation.

If inflation averaged 3.5 percent per year, Table 20.1 is how withdrawals would look for the first 15 years of retirement.

Table 20.1 Four Percent Withdrawal Rate for a $1 Million Portfolio with Inflation at 3.5 Percent per Year

| How Much Would You Sell Each Year? | |

| Year of Retirement | Maximum Amount You Can Sell |

| 1 | $40,000 |

| 2 | $41,400 |

| 3 | $42,849 |

| 4 | $44,348 |

| 5 | $45,900 |

| 6 | $47,507 |

| 7 | $49,170 |

| 8 | $50,891 |

| 9 | $52,672 |

| 10 | $54,515 |

| 11 | $56,423 |

| 12 | $58,398 |

| 13 | $60,442 |

| 14 | $62,558 |

| 15 | $64,747 |

In 2010, researchers Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard, and Daniel T. Walz published “Portfolio Success Rates: Where to Draw the Line” in the Journal of Financial Planning. They examined several portfolio allocations and withdrawal rates between 1926 and 2009.3

Table 20.2 shows a few examples. They found that a portfolio with 50 percent stocks and 50 percent bonds had a 100 percent chance of lasting 30 years if a retiree withdrew an inflation‐adjusted 4 percent per year. If the investor withdrew an inflation‐adjusted 8 percent per year, the odds of the money lasting a 30‐year retirement dropped to 53 percent.

Table 20.2 Where to Draw the Line: Withdrawal Rates and Portfolio Allocations for a 30‐Year Retirement

SOURCE: Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard, and Daniel T. Walz, “Portfolio Success Rates: Where to Draw the Line,” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (no. 4): 48–60.

| Payout Percentages | 3% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 9% |

| 75% Stocks / 25% Bonds | |||||||

| Odds of the money lasting 30 years | 100% | 100% | 98% | 96% | 91% | 69% | 55% |

| 50% Stocks / 50% Bonds | |||||||

| Odds of the money lasting 30 years | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98% | 85% | 53% | 27% |

I can hear what you're thinking. “Only a fool would withdraw 8 percent per year.” That might be true, but if your money were invested with one of the offshore pension companies that I listed in Chapter 4, you would be paying about 4 percent per year in fees. If you withdrew 4 percent of your portfolio's value per year (and you paid 4 percent in fees), that's equal to withdrawing 8 percent per year.

The back‐tested scenarios in Table 20.2 don't include investment fees. As always, it's best to keep such fees as low as possible.

Some say withdrawing 4 percent after inflation may prove to be too much. Skeptics of the 4 percent rule include Michael S. Finke, Wade D. Pfau, and David M. Blanchett. In a 2013 Social Science Research Network paper, they recommend sustainable postinflation withdrawal rates closer to 3 percent (see Table 20.3). Their rationale? Interest rates for bonds and savings accounts are currently lower than usual.4

Table 20.3 Three Percent Withdrawal Rate for $1 Million Portfolio with Inflation at 3.5 Percent per Year

| How Much Would You Sell Each Year? | |

| Year of Retirement | Maximum Amount You Can Sell |

| 1 | $30,000 |

| 2 | $31,050 |

| 3 | $32,136 |

| 4 | $33,261 |

| 5 | $34,425 |

| 6 | $35,630 |

| 7 | $36,877 |

| 8 | $38,168 |

| 9 | $39,504 |

| 10 | $40,886 |

| 11 | $42,317 |

| 12 | $43,799 |

| 13 | $45,332 |

| 14 | $46,918 |

| 15 | $48,560 |

Don't, however, let that spook you. Interest rates might not perpetually scrape along the sea floor. Researchers supporting the sustainability of a 4 percent withdrawal rate considered a variety of back‐tested conditions: double‐digit inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, stock market returns that went essentially nowhere (for the US market) between 1965 and 1982, and a series of American‐led wars.

That said, there's nothing wrong with a 3 percent withdrawal rate. When it comes to money, caution is cool.

By the end of this chapter you'll be able to determine how much money you'll need to retire. You'll also know how much money you should be investing each year to reach your goal.

Could You Cleverly Withdraw More than 4 Percent?

When withdrawing 4 percent of an investment portfolio each year, there's always a chance that you could run out of money. The odds are slight. But if the future delivers investment returns that are far lower than the returns over the past 90 years, there's a chance of going broke. That's why some people prefer to withdraw 3 or 3.5 percent.

Others, however, see a completely different risk. In most historical cases, investors withdrawing an inflation‐adjusted 4 percent per year will die with plenty of money. The Ancient Egyptians thought they could take money to the afterlife. But I wouldn't bet on that.

That's why some researchers have tried to push the 4 percent envelope. Statistically speaking, it's entirely possible to withdraw more than 4 percent and provide high odds that you'll never run out of money. But it does involve some tinkering. Personally, I prefer the 4 percent rule. It's simple and (I hope) reasonably conservative.

But for those who don't mind tinkering and taking a few more chances, the following few paragraphs describe another method.

Jonathan T. Guyton and William J. Klinger explain it in their 2006 research paper, “Decision Rules and Maximum Initial Withdrawal Rates.”5 They believe investors can withdraw an initial 5.2 percent to 5.6 percent of a retiree's portfolio value each year. That might not sound like much of an increase. But 5.2 percent is an initial spending boost that's 30 percent above the 4 percent rule.

The researchers back‐tested two periods: 1928 to 2004 and 1973 to 2004. The first test period began on the eve of history's biggest stock market crash (1929–1930).

The second period coincided with “the perfect storm.” Inflation was high and the markets were set to plunge into the 1973–1974 bear market. It was a time when US stocks fell 45 percent in just two years (UK stocks fell even further).

Guyton and Klinger also wanted to see if their strategy would allow a portfolio to last the duration of a 40‐year retirement. They devised a strategy that would have worked best for portfolios with at least 65 percent invested in stock market index funds with the remainder invested in a bond market index. Here are their rules:

Let's assume that someone retires with $500,000. They decide to withdraw 5 percent ($25,000) from their first retirement year. During their second retirement year, the retiree would withdraw more money to cover that year's inflation.

Let's assume they withdraw $26,000. The money would be removed from the account in the following order of importance. The researchers call this their PMR (Portfolio Management Rule).

- Withdrawals come from the stock market indexes that exceed their goal allocations. If that doesn't cover the $26,000 required, Guyton and Klinger recommend the remaining money should be withdrawn in this specific order.

- Overweight fixed income (bond market index).

- Cash (which would only be available if dividends weren't reinvested).

- Withdrawals from the bond market index.

- Withdrawals from the stock market indexes.

To increase the odds that investors won't run out of money, the researchers say withdrawals shouldn't be increased during years when the portfolio doesn't make a profit. For example, if the second year's withdrawal was $26,000 and the portfolio dropped in value during the third year, the investor would withdraw $26,000, without an adjustment for inflation.

Guyton and Klinger also say withdrawals shouldn't exceed 20 percent more than the initial withdrawal rate. For example, if the initial withdrawal rate were 5 percent per year, investors wouldn't withdraw more than 6 percent of their total portfolio value in any given year (6 is 20% greater than 5). This means retirees would get a “pay cut” from time to time. The researchers call this their CPR (Capital Preservation Rule).

For example, if the investor withdrew $26,000 one year, and their portfolio value dropped from $500,000 to $400,000 the following year, withdrawing $26,000 again would constitute 6.5 percent of the portfolio's total value. But this would break the CPR. To increase the odds of the investor not running out of money, the retiree would be have to cap their withdrawal at 6 percent of their portfolio's value. In this case, that would be $24,000 ($24,000 is 6% of $400,000).

Finally, the researchers have a PR (Prosperity Rule). It allows retirees to withdraw more money during high‐performance years. Assume an investor's portfolio increased from $400,000 to $650,000 the following year. If the investor withdraws $24,000 again (as in the previous example), that would be only 3.6 percent of the portfolio's total value. That's 28 percent below the initial 5 percent withdrawal rate. Guyton and Klinger say that when the amount withdrawn would be 20 percent below the initial withdrawal rate, the investor should boost their withdrawal by 10 percent.

Yes, this is complicated. Such tweaking could also be a pain in the butt. That's why I've stuck to the 4 percent rule in the following scenarios. I also prefer the 4 percent rule for my personal portfolio.

Third‐Culture Kid Sets Her Savings Goal

“Where are you from?” Third‐culture kids sometimes dread that question. After all, they're often from everywhere. Many bounce from country to country while growing up. That said, most third‐culture kids are proud of their cross‐cultural heritage.

Rosanna Herrera is one of them. Now a third‐culture adult, the bubbly 32‐year‐old American was born in Lima, Peru. As a child, she lived in Lima, Peru; Salinas, California; Guadalajara, Mexico; Quito, Ecuador; and Campinas, Brazil.

As an adult, she has worked in the United States; Salvador, Brazil; Cairo, Egypt; and Hong Kong. “My parents are both educators,” says Rosanna. “Early in their marriage they decided to live and teach in Peru. They went back to the US for a few years (when I was between the ages of three and six) but they have been working at international schools ever since.”

Rosanna is a middle school counselor at Hong Kong International School (HKIS). She started her current job in 2017. She hopes to retire when she's 60 years old.

“I would like to retire in a Portuguese‐ or Spanish‐speaking country with nice weather,” she says. “Right now, Portugal and Mexico are high on the list. When you grow up abroad, you can lose that sense of ‘home,’ so when I think about retirement there is no conventional ‘home.’ Being a TCK [third‐culture kid], I am open to retiring in different places, but at the same time, being a TCK, I see most places as an option, so it will be hard to make a decision!”

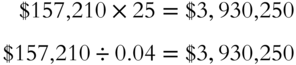

Rosanna has decided, however, that she would like to live on US$60,000 annually when she retires in 28 years. As seen in Figure 20.1, if inflation averages 3.5 percent per year, the equivalent buying power of $60,000 in 28 years would be $157,210.

Figure 20.1 Rosanna's Postinflation Calculation

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

How Much Money Will Rosanna Need?

Rosanna doesn't currently own investment real estate. If she remains abroad, she won't likely be eligible for Social Security payments either. As such, Rosanna will require an investment portfolio that is large enough for her to sell $157,210 per year, while increasing the withdrawals to cover the rising cost of living.

In that case, $157,210 would have to be 4 percent of her total portfolio value. Her investment portfolio upon retirement would have to be worth $3,930,250.

To figure that out, she could do one of two things: multiply $157,210 by 25 or divide $157,210 by 0.04.

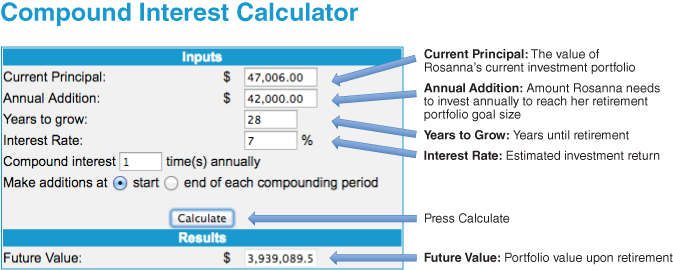

It looks like a massive sum. But Rosanna can reach it. So far, she has accumulated $47,006 in her investment account. As seen in Figure 20.2, if she works 28 more years, she could reach her portfolio goal size by investing about $42,000 a year. Her investments would need to average 7 percent per year.

Figure 20.2 Rosanna's Required Annual Savings Amount

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Again, US$42,000 per year might seem like an outlandish sum for a schoolteacher to save. After all, the best‐paid expats aren't typically educators. Their pay lags behind most professional expat packages.

But Rosanna knows she can do it. There are a couple of things in her favor. Rosanna's salary will increase over time. She's also aware that if she continues to work at top‐tier international schools, she'll make plenty of money over the next 28 years.

Where Can International Teachers Save a Lot of Money?

Teachers at Rosanna's school (HKIS) earn strong salaries. But it isn't the only international school where teachers can save a lot.

In 2015, I interviewed Nathan Schelble. The former high school counselor worked at Singapore American School (SAS). His wife Stacie also worked at SAS. Their nine‐year‐old daughter attended the school for free. “We saved about $100,000 USD a year,” says Nathan. “We traveled whenever we could, and twice each year, we flew back to see family in Buffalo, New York. We even had a full‐time live‐in maid.”

Jane Smith and her husband, Joe (I changed their names to protect their identities), are among a small group of couples saving more than US$100,000 per year at the Canadian International School of Hong Kong. “Most of our colleagues save less,” says Jane, a 45‐year‐old American. “And some might be shocked to learn that there are couples with children that save this much.” Hong Kong, after all, is an expensive city.

Steve Perkins saves about US$58,000 a year at the International School of Bangkok (ISB). The 51‐year‐old Canadian is a single, divorced, father of two boys. They both attend the school. “I live the dream,” says Steve. “I have a car, a maid who cooks for me and does all the household chores. I pay her a great wage, and would consider her almost part of my family. I eat out at least once a week and travel quite a bit.”

I asked Steve if there were any extreme savers at his school. Of Steve's colleagues at ISB, the most frugal couple he knows saves about US$120,000 a year.6

In 2015, I also caught up with my friends Brian and Kristine White. They work at Saudi Aramco Expatriate Schools, in Saudi Arabia.

“Last year [in their first year there] we saved $87,000 USD and we splurged on some really expensive trips,” said Brian. The couple, originally from Springfield, Illinois, took their five‐year‐old son on a five‐week trip to Iceland, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen. They took additional trips to Austria, Singapore, and the United States.

“The company requires that we leave Saudi Arabia for at least three weeks a year,” says Brian. So they give us a very generous amount of money to fly home each year. Last year, our check was for US$24,000.”

In 2016, I interviewed several other teachers at high‐paying schools. I published their stories in my AssetBuilder column, “Where Can International Teachers Make a Lot of Money?”7

These teachers saved similar sums while working at Qatar Academy, in Doha; Seoul Foreign School in South Korea; the International School of Azerbaijan in Eastern Europe; Ihsan Dogramaci Bilkent Erbil College in Erbil, Iraq; Concordia International School in Shanghai, China; and GEMS World Academy in Singapore. I also met a teaching couple that works at the International School of Zug and Luzern. Switzerland is expensive. But the frugal couple still reported saving about US$80,000 per year.

This isn't an exhaustive list of high‐paying international schools. Plenty of others exist. In each case, financially responsible singles and couples (with children) can save a lot of money.

That's Rosanna Herrera's plan.

Robert and Yik Consider Thailand or New Zealand

Robert Kostrzeski met his husband, Yik, in 2013. Robert was working at the International School of Kuala Lumpur (ISKL). Yik worked for the British Council.

The couple wanted a child, so they sought a surrogate mother and their son was born in 2015. The process cost the couple US$50,000, which they withdrew from Robert's savings. They married in 2016. “After we left Kuala Lumpur,” says Robert, “we moved to Thailand, where I worked for NIST International School in Bangkok. Yik worked for a nonprofit organization.”

But because Thailand wouldn't officially recognize their marriage, they moved to Ho Chi Minh City. The Vietnamese government recognizes their marriage, “so we're able to be on the same work visa,” says Robert, “and receive all the benefits of a married couple at Saigon South International School (SSIS).

Yik will likely stay home to raise their son, Oliver, while he pursues another master's degree in counseling from Monash University.

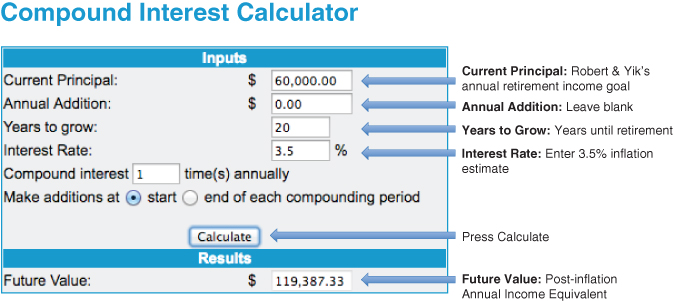

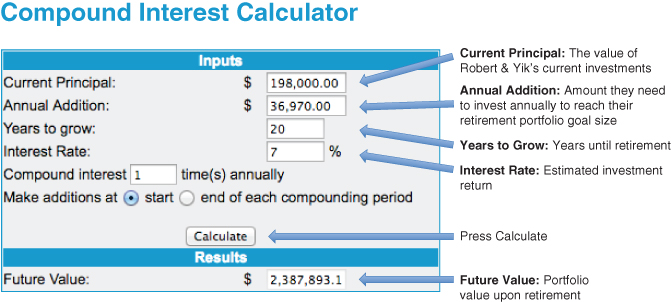

Robert, aged 45, is 12 years older than Yik, so he'll likely retire first. “I would like to have enough money to retire at 65,” he says. The couple currently has a combined total of $198,000 in investments. “I would like to spend about $60,000 USD a year [in 2018 dollars] during retirement,” says Robert. As shown in Figure 20.3, if inflation averages 3.5 percent per year, it would require $119,387 to provide the equivalent buying power in 2038.

Figure 20.3 Robert and Yik's Postinflation Adjustment

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

But Robert will also receive US Social Security payments of US$12,000 per year when he turns 65. Americans can figure out their future Social Security benefits by the checking the website at www.ssa.gov/oact/quickcalc/.

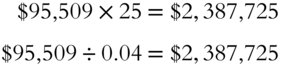

This means Robert and Yik's investments only need to generate US$48,000 a year (in 2018 dollars), instead of $60,000 a year. Once again, if inflation averages 3.5 percent per year, the equivalent buying power of $48,000 would be $95,509 in 2038 postinflation dollars.

This $95,509 would have to be 4 percent of their future portfolio's size. As such, their portfolio's goal size would have to be $2,387,725.

To figure that out, they could do one of two things: multiply $95,509 by 25 or divide $95,509 by 0.04.

Robert and Yik already have a combined total of $198,000 in their investment accounts. As seen in Figure 20.4, if they earn a 7 percent annual return over the next 20 years, they can reach their portfolio goal if they invest US$36,970 USD per year.

Figure 20.4 Robert and Yik's Required Annual Savings Amount

Should This Couple Stress?

Robert says he and Yik worry a lot about their retirement. Currently, they are saving just US$16,800 per year. To reach their retirement goal, they'll need to invest about US$36,970 per year.

They also want another child, which could cost them a lump sum of $50,000. In addition, they are saving some of their income ($4,800 a year) for Oliver's future college expenses.

But plenty of factors are in Robert and Yik's favor. For starters, Yik will still be working when Robert retires, so they might not need to withdraw any of their investments in 2038. Second, Yik will be entitled to a New Zealand pension based on the years he worked there. He expects a further US$8,760 a year.

Student loan debt has also anchored the couple's savings. “I still owe $35,000 USD,” says Robert. “But we plan to have that paid off by June 2018.”

Once that's paid off, it should be easy for Robert and Yik to save enough money.

Finally, they might not even need to spend today's equivalent of US$60,000 per year during retirement. According to Westpac Massey's Fin Ed Centre, the typical urban‐based retired couple in New Zealand spent the equivalent of US$41,789 in 2015.8

If Robert and Yik spend what the typical retired Kiwi couple spends (US$41,789 per year) they could invest as little as $27,100 a year (instead of US$36,970 per year) if they can earn a 7 percent annual return.

It gets even better. Robert and Yik are also considering Thailand as their retirement destination. According to statistics at www.numbeo.com, costs of living in Thailand are considerably lower than they are in New Zealand.

For example, consumer prices including rent are 41 percent lower in Bangkok, Thailand, compared to Auckland, New Zealand.

Such costs are almost 48 percent lower in Chiang Mai, Thailand, compared to Rotorua, New Zealand.

Retiring in Thailand could provide Robert and Yik with plenty of wiggle room. Ideally, they could both retire a couple of years before Robert turns 65. Location, after all, is an important key to early financial freedom.

Couple Plans for a Two‐Country Retirement

Wayne Richmond and his wife, Emma, are among a growing number of expats who don't want to retire in a single country. “We would like two homes,” says Wayne, “so we can move between them each year.” The 42‐year‐old is the chief operations officer at an international printing company in Suzhou, China. He's originally from South Africa. Emma, who's originally from New Zealand, works as an international schoolteacher.

They've chosen Thailand as one of their retirement destinations. They sold a large portion of their retirement portfolio to purchase a mortgage‐free villa in Koh Samui, Thailand. The couple also wants a second home. They might choose South Africa. They already own a rental property in Cape Town, South Africa. It's almost mortgage free. They expect to receive about $15,000 per year from rental revenue, after taxes and expenses, when the mortgage is fully paid.

“We also intend to acquire another investment property in the next few years, most likely in New Zealand,” says Wayne.

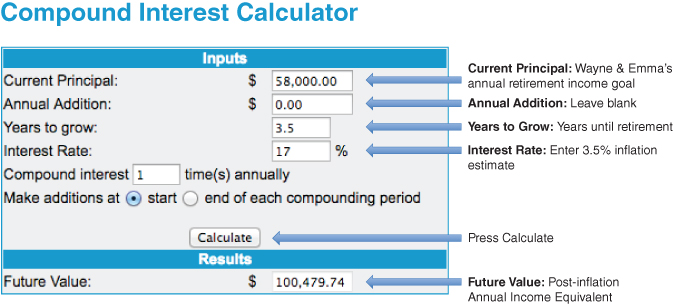

The couple plans to retire in 17 years, when Wayne turns 59. They hope to live on US$58,000 per year (in 2017 dollars). Neither Wayne nor Emma will receive a defined benefit pension, so their future retirement is entirely up to them.

As seen in Figure 20.5, if inflation averages 3.5 percent per year, Wayne and Emma will require about $100,480 a year to provide the equivalent buying power in 2034.

Figure 20.5 Wayne and Emma's Postinflation Adjustment

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Wayne says their properties in Thailand and South Africa won't provide a reliable source of retirement income because they'll be living in them for much of the year. Any seasonal rental income they receive would likely just cover property expenses and property taxes.

Let's assume they don't buy a third property. If they don't, Wayne and Emma would need to fully rely on their portfolio of index funds.

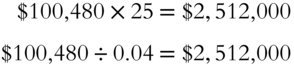

In that case, they would require a portfolio value of about $2,512,000. They could figure that out by multiplying $100,480 by 25 or by dividing $100,480 by 0.04.

“Emma stopped working for the first five years after we met,” says Wayne. “She focused her energy and time on our young boys. In 2016, she went back to work part‐time. We had a late start to building our financial independence, but our current combined earnings allow us to follow an aggressive savings plan to achieve our financially free objective in 17 years' time.”

Wayne and Emma are investing $27,500 toward their children's college expenses. Their two boys, Nathan and Noah, are 7 and 5 years old, respectively.

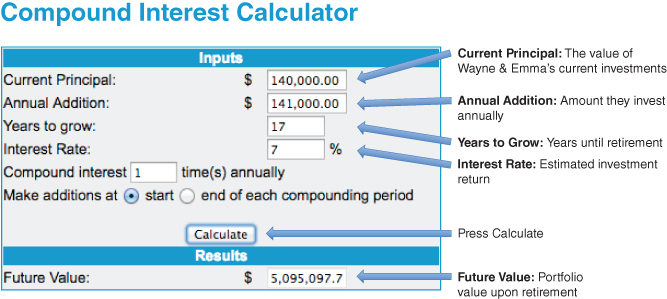

The couple is also investing $141,000 annually toward their retirement.

Their current portfolio value (after selling much of it to buy the property in Thailand) is worth $140,000. As seen in Figure 20.6, if they continue to invest $141,000 per year, and they earn a compound annual return of 7 percent, their portfolio would be worth $5,095,097 in 17 years.

Figure 20.6 Wayne and Emma Have Plenty of Room to Run

SOURCE: www.moneychimp.com

Based on Wayne and Emma's retirement income goal, a portfolio of $5,095,097 would provide them with more income than they need.

If the couple wants to save money for a third retirement property in New Zealand, they would have enough money to do so. Such a property (if they decided not to live in it) would also provide future retirement income.

Wayne and Emma's strong salaries and prudent lifestyle should ensure that they enjoy a fine retirement.

Nobody Can Guarantee a 7 Percent Return

In the calculations above, I assumed a portfolio return averaging 7 percent per year. But your returns might be higher. They also might be lower. Nobody knows what the stock and bond markets will dish out over the next 10‐, 20‐, or 30‐year periods. That's why it's best to be prudent. If you can save more money, do it. Expecting a long‐term return of 7 percent per year is reasonable, based on history. But the stock and bond markets don't owe you any favors. When calculating how much you should be saving, prudent investors might lower their expectations. Would you still be on track if your portfolio averaged a 6 percent annual return? How about a 5 percent annual return?

If you save too much, you can always enjoy the extra proceeds when you're retired. But if you save too little, you might get into trouble.

What If You Retire Right before a Market Crash?

Here's an ideal scenario. The year you retire, the stock market rises and it continues to rise for years.

But here's a scary one. The year you retire, the stock market sinks and stays down for years.

Stock market plunges are great for those who are still working. After all, they're purchasing stock market assets; sinking prices are like supermarket sales. In contrast, retirees are selling their assets, so when the stock market falls, they can lose a lot of sleep. Many worry that they might run out of money if they withdraw an inflation‐adjusted 4 percent per year while stocks fall or sputter.

Fortunately, diversified portfolios don't stay down forever. For example, let's assume that Dave retired January 2001. It would have been one of the worst times to retire. Over the following 10 years, the S&P 500 bounced up and down but it didn't make much headway. A $10,000 investment in Vanguard's S&P 500 index on January 1, 2001, would have been worth just $10,290 by September 30, 2010. That's almost 10 years of treading water.

Assume that Dave's initial portfolio was worth $500,000 on January 1, 2001. Assume, also, that it was identical to the balanced model portfolio model that I showed in Chapter 11, Table 11.1.

- 40% US Bonds (VBMFX)

- 30% US Stocks (VTSMX)

- 30% International Stocks (VGTSX)

Dave begins to withdraw an inflation‐adjusted 4 percent per year. He withdraws $20,998 in the first year of retirement. That's 4 percent of his portfolio value plus an adjustment for inflation. (Note, for these calculations, I used www.portfoliovisualizer.com. It assumes that retirees make an adjustment for inflation during their first withdrawal, which I didn't do when presenting Tables 20.1 and 20.3). US inflation was 3.39 percent in 2001. Each year that follows, Dave withdraws an ever‐increasing sum to cover the rising cost of living.

In 2001, the stock market would have dropped Dave's portfolio 6.0 percent. As seen in Table 20.4, his portfolio would have dropped from $500,000 to $449,866 by December 31, 2001 (after his withdrawal). In 2002, the portfolio would have fallen another 7.32 percent. By the end of 2002, it would have dropped to $395,289.

Table 20.4 Retiring When the Market Falls January 2001–September 30, 2017

SOURCE: www.portfoliovisualizer.com

| Portfolio Starting Value January 1, 2001: $500,000 | ||||

| Year | Annual Portfolio Return | Inflation | Amount Withdrawn | Year‐End Portfolio Value |

| 2001 | –6.0% | 3.39% | $20,310 | $449,866 |

| 2002 | –7.32% | 2.38% | $20,793 | $395,289 |

| 2003 | 23.56% | 1.88% | $21,184 | $465,406 |

| 2004 | 11.71% | 3.26% | $21,874 | $497,986 |

| 2005 | 7.43% | 3.42% | $22,621 | $512,334 |

| 2006 | 14.36% | 2.54% | $23,195 | $562,668 |

| 2007 | 9.08% | 4.08% | $24,142 | $589,571 |

| 2008 | –22.31% | 0.09% | $24,164 | $433,812 |

| 2009 | 22.0% | 2.72% | $24,822 | $504,434 |

| 2010 | 11.03% | 1.50% | $25,193 | $534,895 |

| 2011 | –1.05% | 2.96% | $25,939 | $503,299 |

| 2012 | 11.94% | 1.74% | $26,391 | $536,989 |

| 2013 | 13.62% | 1.50% | $26,787 | $583,305 |

| 2014 | 4.76% | 0.76% | $26,990 | $584,084 |

| 2015 | –1.11% | 0.73% | $27,187 | $550,446 |

| 2016 | 6.15% | 2.07% | $27,751 | $556,574 |

| To September 30, 2017 | 11.77% | $622,091 | ||

By late 2017 (the time of this writing) Dave would have been retired for almost 17 years. In total, he would have withdrawn $305,182 from his original $500,000 portfolio. You're wondering if he's broke, right?

Not even close. Dave's portfolio would have retained all of its original value, despite the fact that Dave would have withdrawn a total of $305,182 since he retired in January 2001. By September 30, 2017, the portfolio would have been worth $622,091.

Let's look at an even scarier time to retire. Susan retires January 2008 with a portfolio valued at $500,000. It's the same as Dave's portfolio: 40 percent US bonds, 30 percent US stocks, and 30 percent international stocks.

Susan doesn't know it, but she's about to retire on the eve of the second biggest crash in stock market history. In 2008, Vanguard's S&P 500 stock market index (VFINX) dropped 37.02 percent. Vanguard's International stock market index (VGTSX) plummeted 44.10 percent.

Because Susan's portfolio also has bonds, it doesn't drop as far as the US or the international stock market indexes. But it still takes a dive. Susan's portfolio drops 22.31 percent in 2008. As seen in Table 20.5, by the end of 2008 her initial $500,000 would have cratered to $368,408. Some of that reduction would have come from withdrawing $20,018 in 2008. But the stock market crash caused most of the damage.

Table 20.5 Retiring with the Financial Crisis January 2008–September 30, 2017

SOURCE: www.portfoliovisualizer.com.

| Portfolio Starting Value January 1, 2008: $500,000 | ||||

| Year | Annual Portfolio Return | Inflation | Amount Withdrawn | Year‐End Portfolio Value |

| 2008 | –22.31% | 0.09% | $20,018 | $368,408 |

| 2009 | 22.0% | 2.72% | $20,563 | $428,893 |

| 2010 | 10.98% | 1.50% | $20,870 | $455,131 |

| 2011 | –1.05% | 2.96% | $21,488 | $428,866 |

| 2012 | 11.94% | 1.74% | $21,863 | $458,222 |

| 2013 | 13.62% | 1.50% | $22,191 | $498,430 |

| 2014 | 4.76% | 0.76% | $22,359 | $499,807 |

| 2015 | –1.11% | 0.73% | $22,522 | $471,748 |

| 2016 | 6.15% | 2.07% | $22,989 | $477,793 |

| To September 30, 2017 | 11.77% | $534,209 | ||

Understandably, she might have been afraid. But the 4 percent rule would have held up well.

If she withdrew an inflation‐adjusted 4 percent per year, she would have withdrawn a total of $194,863 between 2008 and 2016. By September 30, 2017 her portfolio would still be valued at $534,209. Yes, you read that right. Despite retiring on the eve of the biggest stock market crash since 1929–1930, Susan's portfolio would have been worth more on September 30, 2017 than it was when she retired in January 2008.

If you're a DIY investor, scan Tables 20.4 and 20.5. Print them out. Put these tables in your bathroom. Put them in your closet. Stick them on your fridge. Let them be a reminder. Your retirement income shouldn't be threatened, even if you retire in a year when the stock market drops. If you withdraw an inflation‐adjusted 4 percent per year, you shouldn't run out of money.

Now It's Your Turn

Follow the steps above to plug your own numbers into the compound interest calculator at www.moneychimp.com. In 2013, I uploaded a screencast on YouTube. As with the examples above, it shows how to determine how much money you should be saving. I initially created it for international teachers. But I think every expatriate would find it useful. You can find the screencast at the following link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=hM6vUdxzyuk.