8. Mood Lighting

ISO 1250 • 1/50 sec. • f/4.5 • 85mm lens

Shooting When the Lights Get Low

There is no reason to put your camera away when the sun goes down. Your D7200 has some great features that let you work with available light as well as the built-in flash. In this chapter, we explore ways to push your camera’s technology to the limit in order to capture great photos in difficult lighting situations. We also discuss the use of flash and how best to use your built-in flash features to improve your photography. But let’s first look at working with low-level available light.

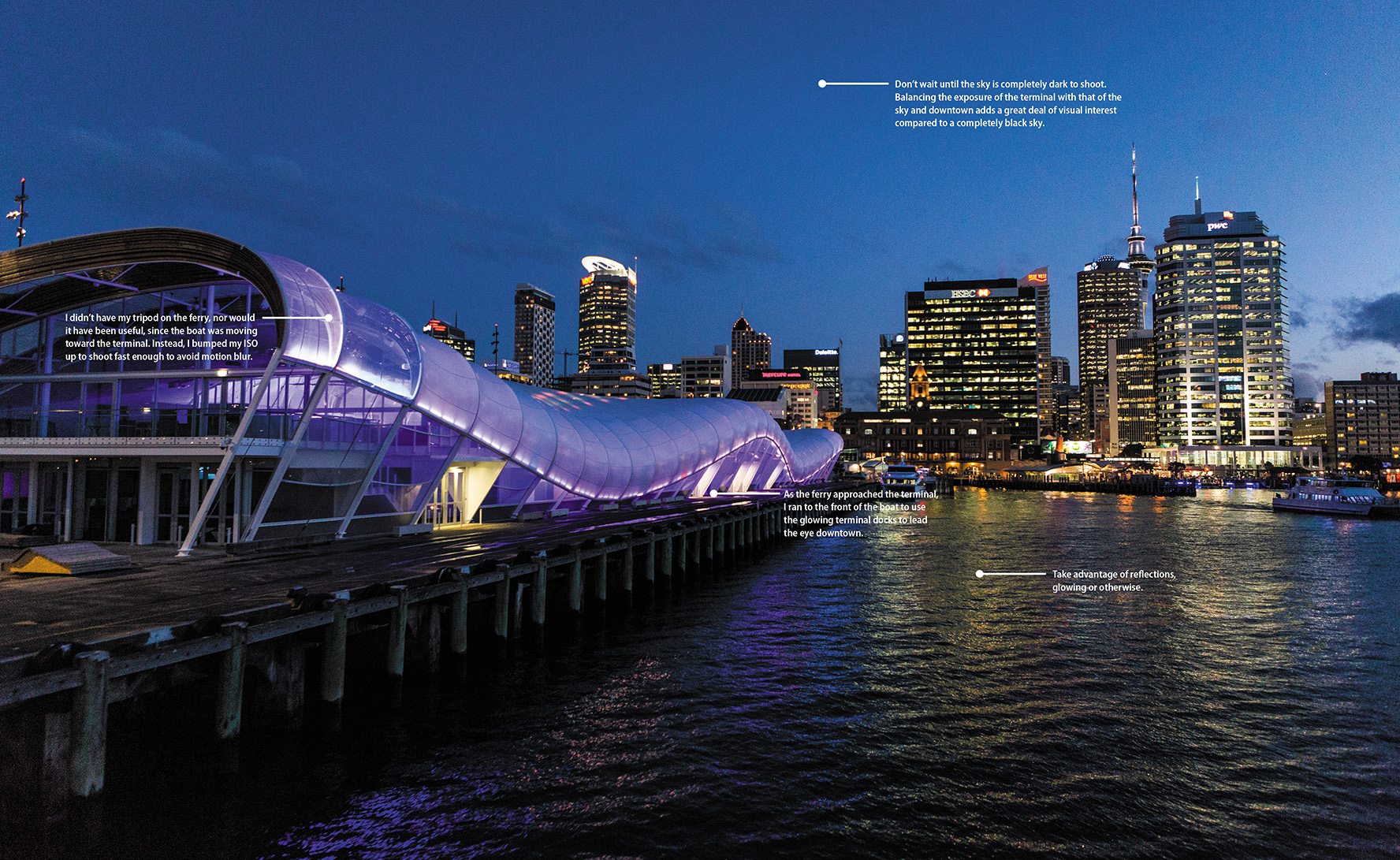

Poring Over the Picture

Auckland, New Zealand, is a beautiful city. I love its aesthetic, and even though there are over a million people living there, it still seems like a smaller community. One thing that is apparent is the attention to the visual aesthetic of city structures, such as this ferry terminal. I was riding the ferry back to the city from a nearby neighborhood, and the purple lights of the approaching terminal balanced well with the sky at dusk and with downtown Auckland. I couldn’t pass up such an attractive and dynamic photographic opportunity!

ISO 3200 • 1/80 sec. • f/2.8 • 24mm lens

Raising the ISO

Let’s begin with the obvious way to keep shooting when the lights get low: raising the ISO (Figure 8.1). By now you know how to change the ISO by using the ISO button and the main Command dial. In typical shooting situations, you should keep the ISO in the 100 to 1000 range. This will keep your pictures nice and clean by minimizing the digital noise. But as the available light gets low, you might find yourself working in the higher ranges of the ISO scale, which could lead to more noise in your image. Everyone has a different tolerance for digital noise, so experiment a bit with different ISO settings and see what your limit is. My tolerance depends on my subject. For my landscape photography I have a very low tolerance for digital noise, but for street photography I have been known to let it slide here and there. I think that with most cameras, the digital noise won’t become apparent until you exceed 2500 ISO and possibly higher, depending upon the image and conditions.

ISO 1250 • 1/50 sec. • f/4.5 • 85mm lens

Figure 8.1 I love shooting neon signs and lit structures at dusk. When they’re exposed well, their glow pops off the darker sky!

Now, you could use a flash and try to avoid bumping up your ISO, but that has a limited range of 2 to 28 feet, depending upon ISO and aperture settings, which might not work for you. Also, you could be in a situation where flash is prohibited, or at least frowned upon, such as at a play or in a museum.

And what about a tripod in combination with a long shutter speed? That is also an option, and we’ll cover it a little later in the chapter. The problem with using a tripod and a slow shutter speed in low-light photography, though, is that it works best when subjects aren’t moving. Besides, try to set up a tripod in a museum and see how quickly you grab the attention of the security guards.

So if the only choice for getting the shot is to raise the ISO to 1250 or higher, my recommendation is to consider turning on your High ISO Noise Reduction (NR) feature. This Photo Shooting menu function is set to Normal by default, but as you start using higher ISO values you should consider experimenting with the High settings. Noise is reduced by applying a slight blur to the image, so my suggestion is to experiment with different ISO settings as well as High ISO Noise Reduction strengths to determine what best suits your needs. (Chapter 7 explains how to set the Noise Reduction features.)

Raising Noise Reduction to the High setting increases the processing time for your images, so if you are shooting in Continuous release mode you might see a little reduction in the speed of your frames per second.

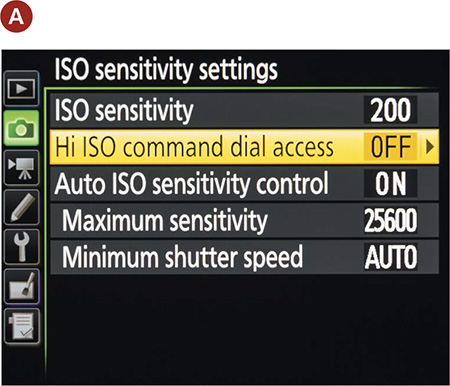

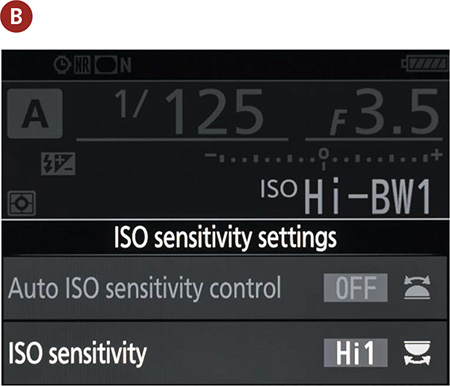

Using Very High ISOs

Is ISO 25600 just not enough for you? Well, in that case, you will need to set your camera to one of the expanded ISO settings. These settings open up several stops of light as you begin to raise your ISO to the maximum setting of ISO equivalent 102400. The new settings will not appear in your ISO scale as numbers, but as Hi-BW1 for 51200, and Hi-BW2 for 102400. The catch, though, is that the two extremely high ISOs can be used only in the Monochrome picture control. In fact, even if you are shooting in RAW, using Hi BW1 or BW2 will switch your format to JPEG only.

How to use the higher ISO settings

1. Press the Menu button, and access the Photo Shooting menu.

2. Use the Multi-selector to navigate to ISO Sensitivity Settings. Press OK.

3. Highlight Hi ISO Command Dial Access (A), press OK, and select On. Press OK.

4. Hold the ISO button. Then rotate the main Command dial while observing the LCD. Rotate the dial until you reach the Hi settings, then release the ISO button.

5. Select Hi-BW1 or Hi-BW2 (these appear as H1 and H2 on the control panel and the LCD) (B).

A word of warning about the expanded ISO settings: Although it is great to have these high ISO settings available during low-light shooting, they should always be your last resort. Even with High ISO Noise Reduction turned on, the amount of visible noise will be extremely high. Try to avoid using extremely high ISOs whenever you can, but don’t skip an opportunity for a terrific shot because you’re afraid to use a higher ISO. The D7200 does remarkably well at 2500 and below, so experiment a little. Remember that a picture never taken is far worse than one with a little noise (Figure 8.2)!

ISO 6400 • 1/15 sec. • f/8 • 70mm lens

Figure 8.2 In order to gain a proper exposure on the movie screen and its reflection on the top of the cars—as well as prevent the car lights in the background from blurring as they moved forward—I had to turn my ISO up to 6400 for sufficient shutter speed. The noise is apparent, but the settings were necessary, and I got a nice movie-going shot.

Stabilizing the Situation

If you purchased your camera with the kit Vibration Reduction (VR) lens, you already own a great tool to squeeze up to four stops of exposure out of your camera when shooting without a tripod. The average person can hand-hold a camera down to about 1/60 of a second before blurriness results due to hand shake. Even if you have arms as big as Popeye’s, you need to use this feature. As the length of the lens is increased (or zoomed), the ability to hand-hold at slow shutter speeds (1/60 of a second and slower) and still get sharp images is further reduced (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Turning on the VR switch will allow you to shoot in lower lighting conditions while reducing hand shake.

Hands off for sharper images

Whether you are shooting with a tripod or even resting your camera on a wall, you can increase the sharpness of your pictures by taking your hands out of the equation. Typically, I like to use a remote shutter release, such as a wireless remote, to avoid placing my hands on the camera. However, I’ve left my remote behind plenty of times. The reality is that whenever you use your finger to depress the shutter release button, you are increasing the chances that there will be a little bit of shake in your image. To eliminate this possibility, try setting your camera up to use the Self-timer mode or the Exposure Delay mode (Figure 8.4). We’re going to discuss the Self-timer feature since we covered Exposure Delay mode in Chapter 1.

ISO 100 • 1/6 sec. • f/8 • 170mm lens

Figure 8.4 When shooting slower than 1/30 of a second, I often set the self-timer to a 2-second delay.

1. Press the Release Mode dial lock, and rotate the dial to the Self-timer icon (it looks like a clock) (A).

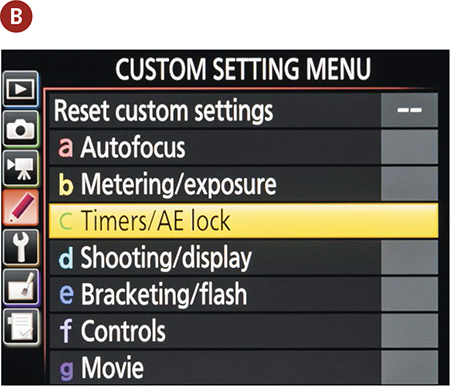

2. Press the Menu button to find the Custom Setting menu. Highlight and select C Timers/AE Lock, then press OK (B).

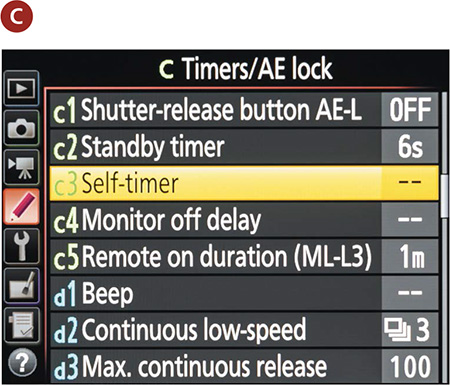

3. Select C3 Self-timer and press OK (C).

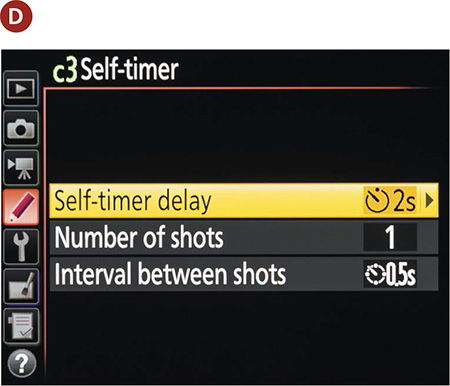

4. Next, highlight Self-Timer Delay and press OK (D).

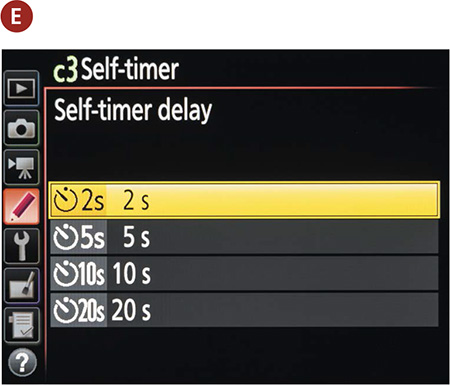

I generally choose 2S (2 seconds) to cut down on time between exposures and reduce my waiting time (E).

Focusing in Low Light

The D7200 has a strong 51-point AF system, but on occasion, light levels are too low for the camera to achieve an accurate focus. You can do a few things to overcome this obstacle, though.

First, you should know that the camera uses contrast in the viewfinder to establish a point of focus. This is why your camera will not be able to focus when you point it at a white wall or a cloudless sky. It simply can’t find any contrast in the scene to work with. Knowing this, you might be able to use a single focus point in AF-S mode to find an area of contrast that is the same distance as your subject. You can then hold that focus by holding down the shutter button halfway and recomposing your image.

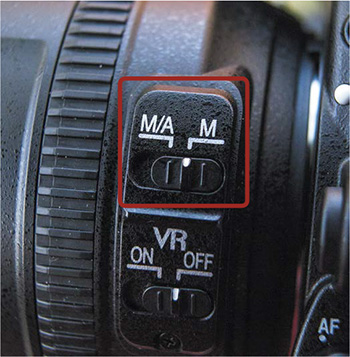

Then there are those times when there just isn’t anything there for you to focus on. A perfect example of this would be a fireworks display. If you point your lens to the night sky in any AF mode, it will just keep searching for—and not finding—a focus point. On these occasions, you can simply turn off the AF feature and manually focus the lens (Figures 8.5 and 8.6). Look for the M/A switch on the side of the lens, and slide it to the M position.

Figure 8.5 You can’t count on autofocus. If the camera just can’t find its focus, take it into your own hands.

ISO 1600 • 30 sec. • f/4 • 24mm lens

Figure 8.6 Even though the moon was bright, there was not enough light for autofocus to find focus on the mountain top. Instead, I focused manually before shooting this long exposure.

Now, I don’t want any emails saying, “Jerod, you broke my camera! It won’t focus!” So make sure to switch your lens back to the A mode at the end of your shoot.

AF-assist illuminator

I know I told everyone that I am not a fan of the AF-assist illuminator in Chapter 1, but that is primarily when I’m shooting people. The D7200’s AF-assist illuminator does a good job helping with focusing by using a small, bright beam from the front of the camera to shine some light on the scene. This light enables the camera to find details to focus on in low-light situations.

This feature is automatically activated when using the built-in flash, except in Landscape, Sports, and Flash Off modes for the following reasons: In Landscape mode, the subject is usually too far away; in Sports mode, the subject is probably moving; and in Flash Off mode, you’ve disabled the flash entirely. Also, the illuminator will be disabled when shooting in the AF-C or manual focus mode, as well as when the illuminator is turned off in the camera menu. AF-assist should be enabled by default, but you can check the menu just to make sure.

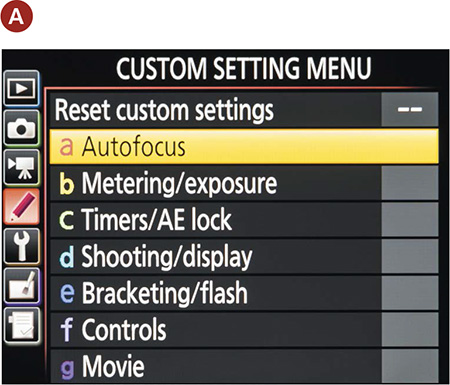

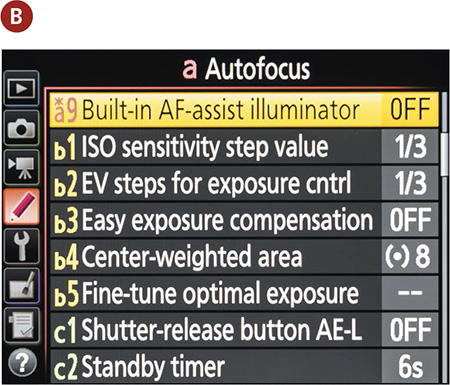

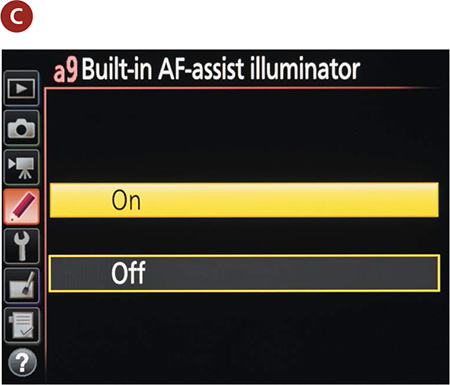

Turning on the AF-assist feature

1. Press the Menu button and access the Custom Setting menu. Navigate to the item called A Autofocus, and press the OK button (A).

2. Highlight the menu item called A9 Built-in AF-assist Illuminator, and press the OK button (B).

3. Set the option to On, and press the OK button to complete the setup (C).

Disabling the flash

If you are shooting in one of the automatic scene modes, the flash might be set to activate automatically. If you don’t wish to operate the flash, you will have to turn it off in the information screen.

To turn off flash

To disable the flash when shooting in Auto mode, turn the Mode dial to the Flash Off symbol (a circle containing a flash with a slash through it).

Remember that if you are shooting in a professional mode, the only way to get the flash to fire is to turn it on yourself. If you are shooting in an automatic scene mode, depending on the mode, it will come on automatically. For example, in Candlelight and Night Landscape modes, it does not come on, whereas in Pet or Night Portrait mode, it is automatically on. If the small flash icon appears in the viewfinder when you are shooting in a particular mode, it means the setting calls for it and the flash will fire automatically. To turn the flash off in any of the scene modes, simply press the Flash Compensation button at the front of camera while turning the main Command dial until the “no flash” symbol appears on the LCD.

Shooting Long Exposures

We covered some of the techniques for shooting in low light, so let’s go through the process of capturing a night or low-light scene for maximum image quality (Figure 8.7). The first thing to consider is that in order to shoot in low light with a low ISO, you will need to use shutter speeds that are longer than you could possibly hand-hold (longer than 1/15 of a second). This will require the use of a tripod or stable surface on which to place your camera. For maximum quality, the ISO should be low; I always try to set mine at 100. Consider turning on the Long Exposure Noise Reduction (NR) to help minimize any hot pixels. (To set this up, see Chapter 7.)

ISO 100 • 25 min. • f/5.6 • 21mm lens

Figure 8.7 Light painting certainly necessitates using a tripod and Long Exposure Noise Reduction. Pointing your camera toward the western side of the sky also raises the possibility that you will capture a certain blue glow in the sky during extremely long exposures.

Once you have Long Exposure Noise Reduction turned on, set your camera to Aperture Priority (A) mode. That way, you can concentrate on the aperture that you believe is most appropriate and let the camera determine the best shutter speed. If it is too dark for the autofocus to function properly, try manually focusing. Finally, consider using a wired or wireless remote shutter release to activate the shutter. If you don’t have one, use either the Self-timer mode or the Exposure Delay mode (covered later in this chapter and in Chapter 1). Once you shoot the image, you may notice some lag time before it is displayed on the rear LCD. This is due to the noise reduction process, which can take anywhere from a fraction of a second up to 30 seconds, depending on the length of the exposure.

Using the Built-In Flash

There will be times when you have to turn to your camera’s built-in flash to get the shot. The pop-up flash on the D7200 is not extremely powerful, but with the camera’s advanced metering system, it does a pretty good job of lighting up the night...or just filling in the shadows.

If you are working with several of the automatic scene modes, the flash should automatically activate when needed. If, however, you are working in one of the professional modes, you will have to turn the flash on for yourself. To do this, just press the pop-up flash button located on the front left of the camera (Figure 8.8). Once the flash is up, it is ready to go. It’s that simple.

Figure 8.8 A quick press of the pop-up flash button will release the built-in flash to its ready position.

Shutter speeds

The standard flash synchronization speed for your camera is between 1/60 and 1/250 of a second. When you are working with the built-in flash in the automatic and scene modes, the camera will typically use a shutter speed of 1/60 of a second. The exception to this is when you use Night Portrait mode, which will fire the flash with a slower shutter speed so that some of the ambient light in the scene has time to record in the image.

The real key to using the flash to get great pictures is to control the shutter speed. The goal is to balance the light from the flash with the existing light so that everything in the picture has an even illumination. Let’s take a look at the shutter speeds in the professional modes.

Programmed (P): The shutter speed stays at 1/60 of a second. The only adjustment you can make in this mode is overexposure or underexposure using the Exposure Compensation setting or Flash Compensation settings.

Shutter Priority (S): You can adjust the shutter speed to as fast as 1/250 of a second all the way down to 30 seconds. The lens aperture will adjust accordingly, but typically at long exposures the lens will be set to its smallest aperture.

Aperture Priority (A): This mode will allow you to adjust the aperture but will adjust the shutter speed between 1/60 and 1/250 of a second in the standard flash mode.

Metering modes

The built-in flash uses a technology called TTL (Through The Lens) metering to determine the appropriate amount of flash power to output for a good exposure (Nikon calls this i-TTL). When you depress the shutter button, the camera quickly adjusts focus while gathering information from the entire scene to measure the amount of ambient light. As you press the shutter button down completely, the flash uses that exposure information and fires a predetermined amount of light at your subject during the exposure.

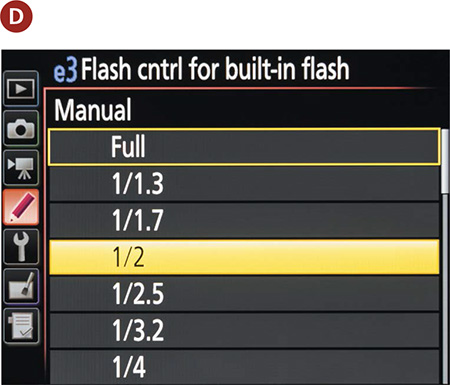

The default setting for the flash meter mode is TTL. The meter can be set to Manual mode. In Manual flash mode, you can determine how much power you want coming out of the flash ranging from full power all the way down to 1/128 power. Each setting from full power on down will cut the power by a third. This is the equivalent of reducing flash exposure by a third of a stop with each power reduction.

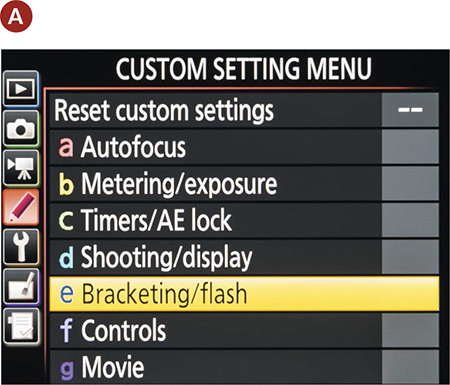

Setting the flash to the Manual power setting

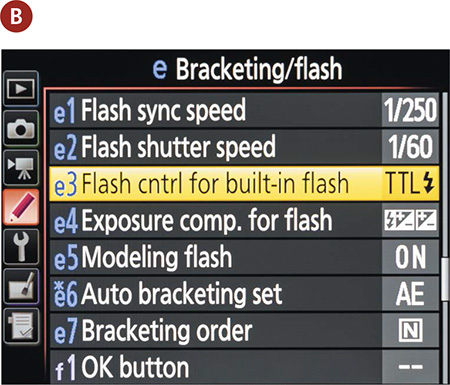

1. Press the Menu button, and then navigate to the Custom Setting menu.

2. Using the Multi-selector, highlight the item labeled E Bracketing/Flash, and press the OK button (A).

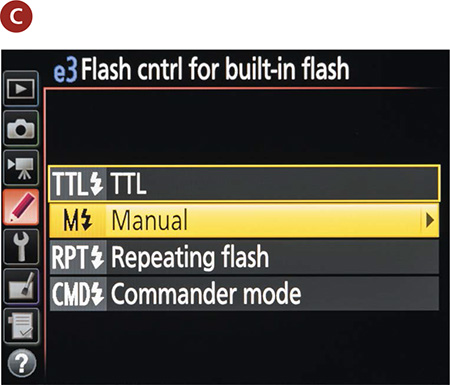

3. Highlight item E3 Flash Cntrl for Built-in Flash, and press OK (B).

4. Change the setting to Manual (C), press the OK button to adjust the desired power—Full, 1/2, 1/4, and so on—and then press the OK button again (D).

Don’t forget to set it back to TTL when you are done, because the camera will hold this setting until you change it.

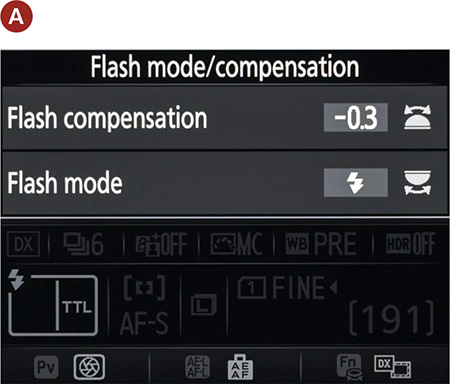

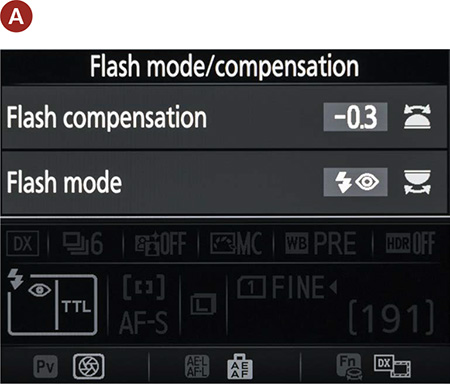

Compensating for Flash Exposure

The TTL system will usually do an excellent job of balancing the flash and ambient light for your exposure, but it does have the limitation of not knowing what effect you want in your image. You may want more or less flash in a particular shot. You can achieve this by using the Flash Compensation feature.

Just as with Exposure Compensation, the Flash Compensation feature allows you to dial in a change in the flash output in increments of 1/3 of a stop. You will probably use this most often to tone down the effects of your flash, especially when you are using the flash as a subtle fill light (Figures 8.10–8.12). The range of compensation goes from +1 stop down to –3 stops.

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/11 • 18mm lens

Figure 8.10 This image was taken with no flash. The exposure for the courthouse in the background is appropriate, but the students in the foreground are too dark.

ISO 100 • 1/160 sec. • f/11 • 18mm lens

Figure 8.11 This image was taken using the flash in TTL mode, but it just couldn’t push enough light to balance out exposures between foreground and background.

ISO 100 • 1/100 sec. • f/11 • 18mm lens

Figure 8.12 By increasing the flash by one stop, I was able to balance out exposure values without blowing out the skin tones.

Using the Flash Compensation feature to change the flash output

1. With the flash in the upright and ready position, press and hold the flash button while viewing the rear LCD (A).

2. While holding down the flash button, rotate the Sub-command dial to set the amount of compensation you desire. Turning to the right increases the flash power 1/3 of a stop with each click of the dial. Turning left decreases the flash power. Release the button when you have made your selection.

3. Press the shutter button halfway and then take the picture.

4. Review your image to see if more or less flash compensation is required, and repeat these steps as necessary.

The Flash Compensation feature does not reset itself when the camera is turned off, so whatever compensation you have set will remain in effect until you change it. Your only clue to knowing that the flash output is changed will be the presence of the Flash Compensation symbol and the amount of compensation in the viewfinder. You’ll notice that as you increase the power, the minus side of the icon disappears, and it appears when you decrease the power. The compensation value will disappear when there is zero compensation set.

Reducing Red-Eye

We’ve all seen the result of using on-camera flashes when shooting people: the dreaded red-eye! This demonic effect is the result of the light from the flash entering the pupil and then reflecting back as an eerie red glow. The closer the flash is to the lens, the greater the chance that you will get red-eye. This is especially true when it is dark and the subject’s pupils are fully dilated.

There are two ways to combat this problem. The first is to get the flash away from the lens. That’s not really an option, though, if you are using the pop-up flash. Therefore, you will need to turn to the Red-eye Reduction feature.

This is a simple feature that shines a light from the camera at the subject, causing his or her pupils to shrink, thus eliminating or reducing the effects of red-eye (Figure 8.13).

ISO 100 • 1/60 sec. • f/4.2 • 38mm lens

Figure 8.13 Notice that the pupils on the image without red-eye (bottom) are smaller as a result of using the Red-eye Reduction feature.

This small adjustment can make a big difference in time spent post-processing. You don’t want to have to go back and remove red-eye from both eyes of every subject!

The feature is set to Off by default and needs to be turned on by using the information screen or by using a combination of the flash button and the main Command dial.

Turning on the Red-eye Reduction feature

1. Press and hold the flash button while viewing the rear LCD (A).

2. While holding the flash button, rotate the main Command dial until the small eye appears in the Flash mode box. This means Red-eye Reduction is on. Release the flash button.

3. With Red-eye Reduction activated, compose your photo and then press the shutter release button to take the picture.

When Red-eye Reduction is activated, the camera will not fire the instant that you press the shutter release button. Instead, the Red-eye Reduction lamp will illuminate for a second or two and then fire the flash for the exposure. This is important to remember, as people have a tendency to move around, so you will need to instruct them to hold still for a moment while the lamp works its magic.

Truth be told, I rarely shoot with Red-eye Reduction turned on because of the time it takes before being able to take a picture. If I am after candid shots and have to use the flash, I will take my chances on red-eye and try to fix the problem in my image processing software or even in the camera’s retouching menu.

Flash and Glass

If you find yourself in a situation where you want to use your flash to shoot through a window or display case, try placing your lens right against the glass so that the reflection of the flash won’t be visible in your image. This is extremely useful in museums and aquariums.

A Few Words About External Flash

We have discussed several ways to get control over the built-in pop-up flash on the D7200. The reality is that, as flashes go, it will render only average results. For people photography, it is probably one of the most unflattering light sources that you could ever use. This isn’t because the flash isn’t good—it’s actually very sophisticated for its size. The problem is that light should come from any direction besides the camera to best flatter a human subject. When the light emanates from directly above the lens, it gives the effect of becoming a photocopier. Imagine putting your face down on a scanner: The result would be a flatly lit, featureless photo—and your eyes would hurt.

To really make your flash photography come alive with possibilities, you should consider buying an external flash such as the Nikon SB700 AF Speedlight. The SB-700 has a swiveling flash head and more power, and it communicates with the camera and the TTL system to deliver balanced flash exposures.

Chapter 8 Assignments

Now that we have looked at the possibilities of shooting after dark, it’s time to put it all to the test. These assignments cover the full range of shooting possibilities, both with flash and without. Let’s get started.

How steady are your hands?

It’s important to know just what your limits are in terms of hand-holding your camera and still getting sharp pictures. This will change depending on the focal length of the lens you are working with. Wider-angle lenses are more forgiving than telephoto lenses, so check this out for your longest and shortest lenses. Using the 18–140mm zoom as an example, set your lens to 50mm and then, with the camera set to ISO 200 and the mode set to Shutter Priority, turn off the VR and start taking pictures with slower and slower shutter speeds. Review each image on the LCD at a zoomed-in magnification to take note of when you start seeing visible camera shake in your images. It will probably be around 1/60 of a second for 50mm.

Now do the same for the wide-angle setting on the lens. My limit is about 1/30 of a second. These shutter speeds are with the Vibration Reduction feature turned off. If you have a VR lens, try it with and without the VR feature enabled to see just how slow you can set your shutter while getting sharp results.

Pushing your ISO to the extreme

Find a place to shoot where the ambient light level is low. This could be at night or indoors in a darkened room. Using the mode of your choice, start increasing the ISO from 200 until you get to 25600. Make sure you evaluate the level of noise in your image, especially in the shadow areas. Only you can decide how much noise is acceptable in your pictures. I can tell you from personal experience that I never like to stray above that ISO 1600 mark.

Getting rid of the noise

Turn on High ISO Noise Reduction and repeat the previous assignment. Find your acceptable limits with Noise Reduction turned on. Also pay attention to how much detail is lost in your shadows with this function enabled.

If you don’t have a tripod, find a stable place to set your camera outside and try some long exposures. Set your camera to Aperture Priority mode and then use the Self-timer to activate the camera (this will keep you from shaking the camera while pressing the shutter button).

Shoot in an area that has some level of ambient light, be it a streetlight or traffic lights, or even a full moon. The idea is to get some late-night low-light exposures.

Reducing the noise in your long exposures

Now repeat the last assignment with the Long Exposure Noise Reduction set to On. Look at the difference in the images that were taken before and after Noise Reduction was enabled. For best results, perform this assignment and the previous assignment in the same shooting session using the same subject.

Testing the limits of the pop-up flash

Wait for the lights to get low and then press that pop-up flash button to start using the built-in flash. Try using the different shooting modes to see how they affect your exposures. Use the Flash Exposure Compensation feature to take a series of pictures while adjusting from –3 stops all the way to +1 stops so that you become familiar with how much latitude you will get from this feature.

Getting the red out

Find a friend with some patience and a tolerance for bright lights. Have them sit in a darkened room or outside at night and then take a picture with the flash. Now turn on Red-eye Reduction to see if you get better results. Don’t forget to have them sit still while the red-eye lamp does its thing.

Share your results with the book’s Flickr group!

Join the group here: flickr.com/groups/nikond7200_fromsnapshotstogreatshots