8

Grow as a Leader

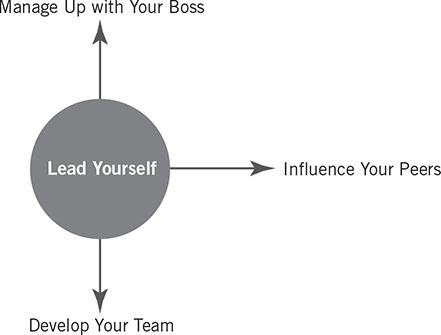

As important as it is for you to lead from where you are, there are even more significant expectations for your leadership when you formally manage people. In addition to leading yourself, you’ll also need to manage up with your boss, influence your peers, and develop your team (see figure).

Leading yourself and others means you’ll be pulled in different directions and faced with difficult situations. In those hard moments, you’ll need to be clear on your “why” as a leader so you can be prepared to bring the best of you to your leadership. This chapter outlines the different ways you’ll be expected to lead yourself and others, including decision-making strategies, managing former peers, supporting team members’ growth by giving feedback, and developing a strong relationship with your boss.

Whether you’re new to management or have been doing this for a while, this chapter will help you develop as a leader and continue to achieve your organizational outcomes.

DECISION-MAKING STRATEGIES FOR ANY SITUATION

As a leader, it’s expected that you’ll be able to make decisions to keep your team and organization moving forward. You won’t always have all the information or time that you might prefer, so you’ll have to develop strategies to help you feel more confident in your choices.

Earlier in my career, my fear of failure undermined the confidence I needed as a leader. This translated into spending far too much time making decisions and then ruminating if I had made the right call or said the right thing.

There are many reasons women might hesitate to make a decision, including feeling like there isn’t enough information or there’s too much information. You could also be dealing with decision fatigue or fear of failure. In my experience of leading large teams in complex organizations, coaching leaders at all levels, and running a business, I’ve learned you have to make the decisions anyway.

It’s not overdramatizing to worry about being wrong. Research shows that women are penalized more harshly than men when they make a wrong decision. In one study by Victoria Brescoll at Yale School of Management, women were consistently judged by their failures, even when they received positive evaluations for their leadership.1

Knowing that your judgment will be questioned and evaluated, often unfairly, it’s no wonder you may experience more hesitation about making decisions! Society has work to do to reduce the double bind on women in leadership, and it’s essential for men to perceive women as strong decision makers and leaders. As we continue to work toward both, here are six strategies you can use to strengthen and reinforce your decision-making skills as a woman leader.

Coach Yourself as You Would a Friend

According to a 2013 research study of women corporate board directors, they tended to engage in more collaboration and consensus-building for their decision-making.2 Based on this finding, one way to improve your decision-making process could be to simulate the experience of discussing with others. For example, talk to yourself as you would coach someone else. What would you advise your best friend or close colleague to do? When you focus on how you would counsel others, you give yourself a bit of distance from the decision at hand, and it could be just enough to see things more clearly. You tend to be harder on your own decisions than you are on others. Because this approach misses the opportunity to increase buy-in from stakeholders, it will be important to clearly communicate your decision to others after it’s been made.

Create More Options

Oftentimes, you unintentionally limit your options when making decisions because you think there is only one right option. Try to find ways to create more options for yourself to bring an abundance mindset and your best thinking to the situation.

If your first option isn’t available or possible, acknowledge it and move on. Ask yourself, “What is my next best option right now?” You’ll help reframe your decision in the context of the moment you’re in.

It’s also important to realize that binary decision-making, which is the idea that there should be one of two options (Option A or Option B), can limit your thinking. In Therese Huston’s book How Women Decide, she suggests that even when you think the scenario has two options, it’s likely you’ve reduced your decision into either yes or no. So, make sure to have three options when fully considering a decision. A third potential option may not occur to you right away, but stretch yourself to consider what else could be possible. My favorite choice is often Option C!

Prepare for Mistakes

Avoiding all mistakes is not a feasible leadership strategy, nor should it be your goal—but it was how I operated for much of my early career. It seemed like the best way to succeed in my position, or at the minimum, to avoid negative feedback. But by recognizing that at some point everyone will make a mistake or fail, you can instead focus on building resilience. It’s not the falling, but rather the getting back up (which often makes you more determined and focused on learning) that will support you in advancing as a leader.

Acknowledge the Role of Emotions

Emotional contagion is when you pass on your emotions, knowingly or unknowingly, to other people. Sigal Barsade of the Wharton School extensively studied this concept, and she discovered that your emotions affect your decision-making—and those around you.3 Though it makes sense that your feelings influence how you see the world, most people are unaware in the moment of the significant role emotions play (or what their exact feelings are, for that matter). Now that you do have this awareness, start paying more attention to the role of your emotions not just to benefit those around you, but to benefit your own judgment, too. A few ways you can reduce negative emotional contagion include:

1. Take time to reset. After every meeting, give yourself 10 seconds to breathe deeply and reset yourself for the next meeting. It’s also especially helpful to reset when you’re working remotely and you transition from a work mindset to home mindset or vice versa.

2. Acknowledge your feelings when something difficult happens. Name the emotion and be specific. Tell yourself, “I feel anxious or upset” rather than “I am anxious or upset” and remind yourself the feeling won’t last.

3. Develop a plan. You might say, “I feel anxious about this upcoming meeting. To help me get through this, I am going to review my notes again and then listen to music.” If you’re around your team members or family members, share this plan with them so they can support you—and learn from your strategies about how to work through emotions.

4. Practice active listening. The more you focus on being present in the moment, the harder it is to overanalyze what happened to you in the past.

5. Engage in activities that remind you of your optimism. This might mean turning to gratitude, doing something kind for someone else, or reaching out to others.

You can’t always avoid getting upset when things happen, but you can increase your self-awareness of your emotions and, as a result, regulate your decision-making.

Consider the Short- and Long-Term Outcomes

When making a big decision, consider both the short- and long-term outcomes. To put things into perspective, ask yourself, “Will delaying or changing the decision make things significantly better?” Having the qualifier will help you consider whether you truly need to gather more information or evaluate other possibilities. If it won’t make things significantly better, proceed and focus on making progress rather than making it perfect. Even incremental progress is worth celebrating. There is rarely a perfect decision anyway! You have to take the risk in order to innovate.

Take the First Step

Sometimes the most important decision is to take the first step. My mantra might help you with this: you’re making the best decision you can with the information you have at the time. I find this reassuring, because you can change course in the future if you have new information that suggests going in a different direction.

Though much of the same advice offered to women about decision-making could also apply to men, the experiences women have in the workplace suggest a more nuanced approach. Women will be evaluated more negatively for their leadership solely on the basis of gender (ugh!), so it’s not just your decisions, but the way people perceive your decisions.

In my own career, I decided to focus more on being respected than being liked. I did this by acknowledging the value I bring to the organization instead of waiting for others to validate me. I chose to remain focused on how to best serve others, even when it was hard or sometimes unpopular. I also learned to listen to my intuition again, which has always guided me in making big decisions. The answers were there because I had the experience to back them up, but I had stopped hearing them through the noise of everyone else’s opinions.

Becoming a stronger, more confident decision-maker didn’t happen overnight. Instead, I learned over time how to manage ambiguity, balance data and intuition, and harness my emotions. I also practiced decision-making to make informed choices with less effort. And I gave myself grace to learn from my decisions, even the “wrong” ones.

The role of a leader is to keep moving things forward, making the best decisions you can on behalf of the team and organization, with the information you have.

FROM PEER TO SUPERVISOR

As you advance in your career, especially if you’re able to grow within the same organization, it’s likely that you’ll experience managing people who were formerly your peers. They may have even been your friends.

I lived this: in my first big management role, I went—overnight—from being the friend you went out for margaritas with, to being the boss who did your performance evaluations. It was one of the biggest professional challenges I’ve experienced—even though I tried to prepare for this.

You see, throughout the interview process for this promotion, I was asked the same question over and over: “How will you handle the transition from peer to manager?” I had anticipated this question, as I was preparing to go from individual contributor to my first significant role managing people, and I would remain within the same team. I shared my thoughtfully planned and practiced answers during the interviews and, fortunately, got the job.

In the weeks leading up to the new role, I read every book and article on this topic, attended multiple seminars, and talked to mentors and trusted advisors. All of the advice made it sound like it might be difficult at first, but it would go smoothly eventually. In the first week, I realized none of the advice or learning truly prepared me for going from peer to supervisor.

When I first started out as a manager, I mistakenly thought I could keep doing everything I had done as a superstar employee, but perhaps better, and that would be the key to leadership. After all, most people are tapped for management roles as recognition for what they did well as individual performers.

I ended up doing everything myself, though—which meant I didn’t bring my team along with me and left me feeling burnt out and alone. And this led me to realize the first and most important lesson for new managers: your job is not to be the superstar anymore. Now your job is to support your team. The reason a team exists is to accomplish more than any individual could on their own.

Here’s what I would do differently and how you can be intentional with your immediate next steps in order to have a successful transition from peer to supervisor. (Many of these things will help every manager, not only those who are going from peer to supervisor.)

Acknowledge the Transition

Make time to meet with each direct report individually with the purpose of establishing your new boss / team member relationship. During this meeting, ask them what they enjoy most about their work and how you can help them thrive in their role. You can share your leadership style and open a dialogue regarding any questions or concerns they may have.

Your transition into a management role will likely be as uncomfortable for you as it is for your team members, so go ahead and acknowledge this instead of pretending it doesn’t exist.

As part of your new role, things at work will have to change, and you may have mixed feelings about this. It’s okay to feel sad about missing out on your friendships while also being excited about what is ahead for your career.

Create a Distinction in Your New Role

You’ll want to clearly define the new boundaries that will exist in your relationship. This means you can’t be there to sit and listen while your team member talks through every step of a project like you might have before. To create a distinction in your new role as the boss, remind team members that you believe in their abilities, are available as a resource, and look forward to project updates in your next one-on-one meeting. This also means your team members shouldn’t drop by your office to share the latest company gossip, but you do want them to feel comfortable raising concerns about things happening in the organization.

As I worked through my leadership transition to manager, I had to learn the difference in the impact of what I said when I was in a position of authority, even if my intent was the same as when I was a colleague. When you’re the boss, your feedback carries more weight. One of my favorite descriptions of this is that a boss’s whisper can sound like a shout.4 For example, you may have been the go-to editor for your friend’s important work emails, and it can be interpreted differently when you mark up their documents as the boss.

Before you offer feedback, consider if you’ve laid the groundwork for this to be productive for both of you, such as rebuilding trust and clarifying new roles. You can also remind them you’re here to support them (which, of course, you also did as a friend, but now it is part of what’s expected of you as their boss). Then be specific about what needs to be improved and actionable steps to do so.

For example, “I’ve always admired your consistency and clarity in your reports. The last few reports haven’t reflected the level of analysis needed. What can I do to best support you in getting back on track?”

Make a point to proactively tell your team members specifically about what they do well, too. This type of feedback from a boss is also amplified when received by a team member. It’s where your whisper-turned-shout factor can make a positive difference!

Maintaining (or Not Maintaining) Work Friendships

The perspectives are mixed on whether you should thoughtfully maintain work friendships with direct reports or keep the boss/subordinate roles separate. I struggled with this in my first peer to manager transition.

I attempted to do a hybrid version where I would announce which “hat” I was wearing when talking to a team member (“boss” or “friend”). The idea was that I could still maintain at least part of the friendship in certain circumstances. But this meant I was switching back and forth frequently, sometimes in the middle of a single conversation, and got lost on which hat I was wearing when. I learned quickly that this strategy wasn’t going to work, and I decided it would be clearer to have only professional relationships with my former peers.

But it wasn’t easy.

The first time I saw the team heading out for cocktails after a work event, I felt left out because I wasn’t invited, even though I knew that would eventually happen. It still hurt because I had been included in those invitations just a few months prior.

One more lesson of leadership is that your choices and actions are being watched. So if you choose to remain friends with your direct reports, the responsibility is on you to treat all of your team members equitably. You wouldn’t want to be seen as playing favorites with select team members.

As I’ve developed as a leader, I’ve found my position on work friendships has evolved. Like all relationships, it takes trust, communication, and compassion.

Provide Vision and Clarity (Not Answers and Solutions)

I had always prided myself on being the friend and colleague who supported others, whether serving as a trusted resource for questions about work, being counted on for coffee breaks and peer mentoring, or putting out work fires. The difference as a manager is that you can’t answer everyone’s questions all the time (nor should you), and your role is to clarify the work for others, not do it all yourself. I had to learn that sharing my expertise as a manager was often less valuable than encouraging others to find the answers within or for themselves. I also learned the hard way that it’s my job to coach them to solve their problems and manage difficult situations, not necessarily do it for them.

During a conversation with a mentor about some of my challenges as a leader, she reminded me that my focus should be vision and clarity (versus answers and solutions). She recommended that I needed to stop “taking on the monkey,” a phrase popularized by a Harvard Business Review article from the 1970s that is still relevant today.5 In corporate speak, this happens when your team members put their work problems onto you: hence you take the monkey on your back.

You can break this habit by helping draw out your team members’ thinking instead of giving your opinion first. For example, try asking your team member questions like “What factors are you weighing in making this decision?” “What do you think the next step should be?” or “How should we handle this challenge?” Asking them their thoughts helps you build buy-in and shows you value their perspective.

Remember: the leader’s role is not to solve problems, but to help their team become better problem-solvers.

Ask for Help

During this transition, one of the things I missed most was having someone to help guide me through so many difficult decisions and situations. What I should have done was reached out to my boss and asked for help, but I didn’t because I mistakenly thought that would be a sign of weakness or failure in my new role. Asking for help means that you still have more to learn, but it doesn’t invalidate the experience you already have. I hope that you respect your boss as a leader and can count on them for insights. If not, I recommend finding an established colleague in your field you can turn to when you need guidance.

I eventually worked with an executive coach to support my leadership development, and she helped me see what was holding me back, both in my organization and in myself. Together we developed a plan for the areas I wanted to work on—and what I could control. She reminded me what my strengths and values were and showed me how to leverage them differently. It was a life- and career-changing experience that I highly recommend, if you have a chance to participate.

I’ve since left the organization where I had my first big management role, but the memories of what I wish I had done differently haven’t left me. When you move on, make sure you take the learning with you. Better yet, share that learning with others. In turn, you’ll be able to make meaning from your experiences.

All leadership transitions are difficult. I was so busy trying to do what everyone else suggested I do that I forgot what made me a great colleague or friend in the first place—caring about team members as people.

GET BETTER AT GIVING FEEDBACK

Giving effective feedback will be one of the most consequential parts of your job as a leader, because it’s how you can contribute to your team members’ growth.

I wasn’t always comfortable giving feedback. Earlier in my career as a manager, I vacillated between wanting people to like me and feeling like I needed to assert my authority. This meant I either shied away from saying anything that would upset team members or went in the total opposite direction and told it like it was without considering how the other person would receive it. Neither worked.

It took me a long time to learn how my feedback could support team members’ growth if delivered in a way that focused on building relationships. Once I did, I understood that it is possible to be direct and compassionate at the same time.

To be a great leader, you’ll need to get comfortable communicating compassionately and clearly with your team members because you genuinely believe in their potential and care about their growth. Here’s how to start.

Include Feedback as a Team Value

Have ongoing discussions about the importance of feedback, beginning with onboarding new staff and continuing throughout their tenure. Effective feedback has to be built on trust and psychological safety, which allows team members to feel safe at work. When someone feels this way in the office, they know they can speak up and share their thoughts without negative repercussions, and they can take risks to innovate. It takes intention and trust to build this kind of work environment, so be sure to openly talk about feedback in the context of learning and innovation to create understanding of expectations. This should happen well before delivering any actual feedback and isn’t meant to be used only in performance evaluations.

Another way to ensure that feedback is a part of your team culture is to provide coaching for all managers on the team about how to give feedback and encourage them to coach each other, too. And you should expect and encourage feedback from your team to you, too. In the same way your feedback should help your team members grow, you will also grow from understanding what your team needs from you as a leader. Work hard to create an environment where it’s possible for staff to speak up.

Structure Your Feedback

When you deliver feedback, first reaffirm that you care about your team member’s growth. Then be specific about what behaviors you want them to continue doing (reinforcing feedback) or what behaviors you want them to stop doing (redirecting feedback) and actionable steps to do so.

EXAMPLES OF REINFORCING FEEDBACK

I really appreciate when you turn your materials in by deadline.

I’d like to see you do more of the budget analysis in order to achieve our financial outcomes next quarter.

In these examples, I indicated what a team member already does well or what they could do more of, so they have a clearer understanding of what they should continue to do to be successful in their role. I also made a point to connect their efforts to the organization’s goals, so they can see how they contribute to the broader organizational outcomes.

EXAMPLE OF REDIRECTING FEEDBACK

You have missed a few deadlines on this project. What’s contributing to that? When you miss deadlines, you also affect your team members as they are relying on you to complete your section to finalize this project. If you anticipate missing a deadline in the future, please tell me as far in advance as possible, so we can determine what to do.

In this example, I stated what I saw happening, asked questions to show I care about them and want to know more about their workload, and shared how this behavior affects others. I also clarified what my expectations are, so the team member understands what to do in a situation like this and knows I’m there as a resource and partner.

You may also find ways to help employees reflect on their own strengths and growth areas by asking questions, instead of only sharing your perceptions. For example, instead of immediately sharing your thoughts on a meeting, ask, “How do you feel that meeting went?” If there was something you noticed they could have done differently in advance of the meeting, you could certainly state what you think, or you could dig a little deeper to understand by asking, “What was your process to prepare?” The more you can get past the surface to understand a team member’s motivations, values, or processes, the better you’ll be able to support them. The more they can see the learning moment for themselves, the likelier they’ll be to change behaviors.

Time Your Feedback

Consider appropriate timing and place for feedback, but don’t overthink it. I don’t believe in offering feedback in front of other people (unless a team member is doing something to negatively affect someone else in a way that requires addressing immediately). Instead, find a time and place where you and the team member can speak privately.

Be sure to account for a team member’s frame of mind, such as if a team member has a lot going on outside of the office that could be affecting their performance, and try to give some space and grace, so your feedback can be heard. You might ask them, “Does this feel like a good time to talk through some things I am noticing?”

If they react poorly and ask to wait until the next day, respect this. You don’t, however, need to wait for a formal one-on-one meeting, especially if it’s a week or two away, because it might be hard to remember pertinent details with so much time in between. Also, if there is something time-sensitive that you need to share with your team member, you don’t need to ask permission.

I coach managers on my team and clients to give what I call “flash feedback,” for example, directly following a meeting, so the person doesn’t forget the circumstances and can benefit from learning in the moment. Plus, when team members know feedback is a value, this is something they will be prepared to hear.

Remember to Give Positive Feedback, Too

Feedback tends to get a negative reputation because it can refer to something that needs to be improved. Remember the importance of positive feedback, too! When offering praise or recognition, center it on the other person. Specifically acknowledge the achievement so your team member knows what they did well and what to repeat in the future. Praise the person’s efforts and how it helps the organization (not how it benefits you). Research shows that this increases the likelihood of positive emotions for the feedback recipient—and builds relationships.6

Offer positive feedback genuinely and authentically (people can tell when it’s not) and more frequently than you might think is necessary. In a hybrid work environment when your team members may feel more disconnected from their work and each other, this encouragement is especially meaningful.

MANAGE UP WITH YOUR BOSS

Developing a positive relationship with your boss is imperative. It can define how you feel about your job—and affect how your boss views your work.

But it’s a balance. You want your boss to trust you and support you, but you don’t want to compromise who you are to achieve that. You want to be someone they can count on, but you don’t want to be the yes-woman for everything either. So, what can you do to set yourself up for success?

“Managing up” is the common term for knowing how to work well with your boss. Here’s what it’s not: sucking up. And it’s most definitely not manipulative. Rather, it’s about opening the lines of communication, and it benefits both you and your boss.

Here are four things you can do to develop a strong relationship with your boss:

Learn Your Boss’s Expectations and Style

You can learn your boss’s leadership style by observing and listening. You can also ask questions about what kind of communication works well for your boss, how they approach their work, and what they value. Then follow through accordingly.

If they want to be copied on every email, keep them included. If they prefer brevity, focus on speaking succinctly. It’s beneficial for you to share with your boss about your own style and how they can best support you, too.

Understand What Matters to Your Boss

You will need to understand what your boss’s priorities are and how they align with yours. Then it’s your job to connect the dots to help advance those projects. I like to get a sense of what keeps my boss up at night, because my goal is to solve for what’s valuable to the organization (and help them sleep!).

Over time, figure out ways to anticipate your boss’s needs and offer to be helpful. Here’s how to put this in action: ask your boss, “What can I take off your plate?” This shows your genuine interest in supporting them and gives you access to higher-level projects. Time this strategically, so you don’t burn yourself out, such as before they go on vacation or if they seem particularly overwhelmed. This is a way to stretch yourself and move things forward for your boss—and it has worked for me to advance my career.

Give Feedback to Your Boss

It can be challenging to know how to disagree with your boss, but keep in mind that a good boss will have hired you because they value and respect your perspective and input—both of which are necessary to advance the organization and support them. Figuring out how to effectively give feedback to your boss is an essential component of building trust with them.

Take some time to reflect on appropriate timing and be clear on what your goals are before approaching your boss to share your thoughts. You might even ask your boss if they’d be open to you sharing an alternate perspective. This gives a signal that you might be sharing something your boss isn’t expecting and gives buy-in for you to proceed.

The goal is to make it comfortable for your boss to listen thoughtfully to your perspective. Stay focused on the situation, not your perception, judgment, or the story you may be telling yourself. Be confident in delivering your message, but humble in your delivery. I recommend that you also affirm your boss’s authority. I like to use phrases like “I defer to you on this,” “I welcome your expertise,” or “Thank you for the chance to share this perspective” in these situations.

Connect with Your Boss as a Person

When you’re feeling disconnected from your boss or frustrated with how they’re handling something, it helps to remember that your boss is human and approach them with empathy. Keep in mind that your boss has many competing priorities and is likely experiencing their own learning and challenges.

Try connecting with your boss on a personal level. Your goal is to better understand who they are, not to be best friends. In a casual conversation, ask about their weekend or what hobbies they have. In a one-on-one meeting, ask them to share a story about their career and what helped them be successful or what they wish they had done differently. If you’re able to see your boss as a whole person—in some ways, just like you—it can help you relate to them and ease some of the work frustrations you have.

Building a positive relationship with your boss is a critical skill to your success in a work environment. Find ways to understand how your boss’s goals and yours align and then work toward those outcomes—together.

• • •

Leading yourself and others is a significant responsibility. Here’s the thing that no one ever told me, but I learned over time: leadership is one of the most rewarding and challenging things you can do at work. When you commit to serving and supporting others in being the best version of themselves, you truly have the power to change lives—including your own.

BOLD MOVES TO MAKE NOW

Write down what motivates you to lead people and one thing you want to be known for as a leader.

Choose one decision-making strategy you will try this week when you’re feeling stuck.

Practice communicating with compassionate directness in a feedback conversation or in asking for what you want.