2.

The Planning and Development Process

Planning may proclaim to be a technical process, but in practice this is rarely the case. The British planning system is based on a set of broad policy frameworks within which development consents are negotiated. It involves people and powerful interest groups with different agendas and tends in reality to be subjective, unstructured and intuitive. But sometimes it can find bespoke solutions that are considerably better than rigidly applied zoning codes or land use allocation plans.

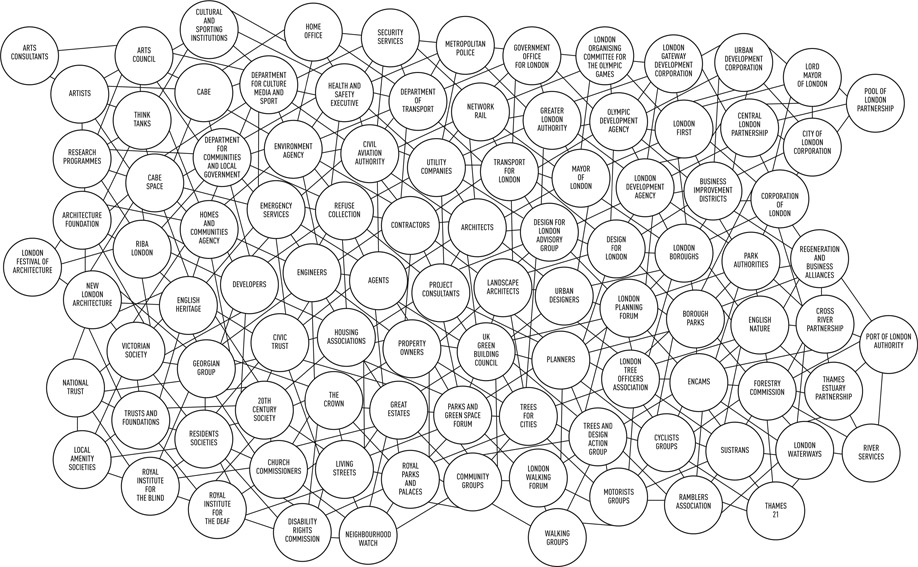

Figure 2.1:

The complex stakeholder networks involved in the design of one open space in London.

It is a common misconception that new urban areas owe their existence to individual agents, whether the planner, the architect or the developer. In a democracy, power is diffused between multiple stakeholders – landowners, government bodies, politicians, technical experts, community and interest groups, individuals and development companies. Planners, architects and their clients have to be able to navigate this complexity, and if possible, broker agreements. Figure 2.1 was produced by Design for London1 to illustrate the number of different stakeholders that might be involved in the design and construction of one piece of new open space in London. It is not meant to be easy to understand. It is complex, but occasionally if one can find a path through this complexity, put the right people together and understand how different agendas can be reconciled, change can happen. And sometimes this can be beneficial. Planning is not just about control and regulation; it is about brokering agreements and making deals.

The UK Planning System

The criteria for deciding whether or not to give consent to a development proposal are pretty clear. Broadly, there are two questions that need to be addressed. First, does it comply with the policies set out in the approved local plan (the Local Development Framework) and second, would it harm the character and amenity of its immediate neighbourhood or the wider area? Subject to these two basic questions, there is a presumption in planning law that planning consent should be granted unless there are clear grounds to the contrary. Although economic viability will almost certainly be raised in the course of negotiations, the question of whether the developer is going to make a large profit should not come into the question.

While the criteria for determining a planning application may seem straightforward, their interpretation and application are not. The British planning system is long established, much reformed and, because consent can bestow a huge increase to the value of the land, is highly contested (for a brief summary of the English planning system, see textbox on pp.10–11). The system dates from the 1940s2 as a response to the economic conditions in the immediate aftermath of the war. It was designed to manage competing social and economic needs within a small, congested, but essentially pluralistic island. Effectively, the Planning Act removed – basically nationalised – many of the rights of the landowner concerning how they might use and develop their land. The process of consenting development, and therefore restoring development rights back to the landowner, was vested in elected politicians and planning professionals. These decision-making powers are constrained by the law. Decisions have to be reasonable and based on an agreed plan that itself has been subject to public scrutiny.

The system’s fundamental purpose is to manage competing social, economic and environmental interests. This puts planning into an inherently political arena. Under the British planning system, notwithstanding what is said in a statutory plan, each application has to be considered on its own merits, in other words, negotiated. This is different from many other planning systems in the world where planning and land use zoning can be quite specific. It can produce very good bespoke developments when it works, and delays and frustrations when it does not. The safeguard in the system is the right of a developer to appeal to an independent inspectorate. In significant schemes this will result in a public inquiry where all aspects can be considered, often with protagonists represented by expert witnesses and senior lawyers. While recognising the value that such public scrutiny can bring, the quasi-judicial

The English Planning System3

National government

Secretary of state for communities and local government: The secretary of state (SoS) oversees the planning system and sets national legislation and planning policy. The SoS also oversees the appeals process and occasionally ‘calls in’ major applications for public inquiry (see textbox on planning appeals, p.57). The National Planning Policy Framework (March 2012) consolidated all previous policy documents, guidance and circulars, and provides national planning policies for England covering the economic, social and environmental aspects of development. Prior to this, government policy was set out in thematic planning policy documents and guidance notes. These policies must be taken into account in preparing local plans and are a ‘material consideration’ in deciding planning applications.

Regional government

The mayor and Greater London Authority: In London, the mayor is responsible for producing a strategic plan for the capital (the London Plan). Local plans in London need to be in ‘general conformity’ with the London Plan, which guides decisions on planning applications by London borough councils and the mayor. The mayor is consulted on major developments and has powers to direct refusal.4

Local government

The London boroughs are responsible for most planning matters – preparing local plans, and determining planning applications. They are known as the Local Planning Authority (LPA).

- Elected councillors: In London, councillors are elected locally every four years. The controlling party is that with the most elected councillors. They set council policy and make most key decisions. Some councillors will sit on the planning or development control committee (which makes decisions on planning applications). All councillors have a role to play in representing the views and aspirations of residents in plan-making and when planning applications affecting their ward are considered.

- Officers: Local planning authorities appoint planning officers to assist with the operation of the planning system. Most minor and uncontroversial planning applications (around 90 per cent) are decided through delegated decision-taking powers to officers. Larger and more controversial developments are decided by a development control subcommittee, guided by officers’ recommendations.

- Local plans: Any planning application must be determined in line with the development plan (the LDF and the London Plan). Local plans set out a policy framework for the future development of the area, engaging with their communities in doing so. They address needs and opportunities in relation to housing, the local economy, community facilities and infrastructure. The local plan is examined by an independent inspector whose role is to assess whether the plan has been prepared in line with the relevant legal requirements.5 Most local plans are effectively policy documents with accompanying illustrative maps.

- Planning permission: Once the local planning authority has received a planning application, it will publicise the proposal so that people have a chance to express their views. The formal consultation period is normally 21 days. Comments will be taken into account, which are relevant to the proposal and ‘material’ to planning. ‘Material’ considerations, in broad terms should relate to the use and development of land. Each application is considered on its merits. A local planning authority has up to 13 weeks to consider major development, such as large housing or business sites, although an extension of time may be agreed between the developer and the LPA.

- Community benefits through planning obligations: Most development has an impact on infrastructure, such as roads, schools and open spaces. It is accepted that developments should contribute towards the mitigation of its impact through a charge based on the size and type of proposal. At the time of the King’s Cross development, planning obligations were secured under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended). A developer may be required to enter into an obligation to, for example, provide affordable housing or provide additional funding for services. Any planning obligation must be directly related to the development and be fair and reasonable (see textbox, below, on CIL and section 106 agreements).

nature of the proceedings has pushed local planning into a defensive position, entrenched behind rafts of policies that are often obscure and occasionally conflicting. Because the whole system is subject to precedent, it can be over legalistic and err on the side of excessive caution. Consequently, resources are often drained away from the creative planning of new places and neighbourhoods into a target-based, process-driven, regulatory system.

The Role of Planners

Section 106 Agreement and the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL)

Many planning consents include a set of separately negotiated legal obligations under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, commonly known as a section 106 agreement. It can cover the provision of anything that is required to offset any wider (negative) implications of a development. It is commonly used to secure affordable housing, new schools, health clinics, open space and the infrastructure necessary to support the development (including contributions to upgrade public transport). There are clear tests regarding eligibility; any demand has to be reasonable and related to the development. Although the value of the ‘planning benefits’ negotiated should only relate to those that are strictly necessary, inevitably the value of the section 106 agreement is seen by some as a measure of negotiating prowess.

The system is now in transition to the CIL, which came into force on 6 April 2010 through the Community Infrastructure Levy Regulations 2010. The CIL aims to provide a more clear-cut, if less flexible approach relating the size of the developer’s contribution directly to the development’s square footage.7

Successive governments have criticised planning as a brake on economic growth and as a convenient scapegoat for lack of investment in housing and infrastructure. In 2011 the prime minister, David Cameron, described planners as ‘enemies of enterprise’.6 Policies to roll back regulatory control have therefore been a consistent theme of government. The four years that the Heathrow Terminal 5 planning inquiry took (with a further two years awaiting a ministerial decision), are often cited as an example of the suffocating nature of the planning system. This is of course true but often these delays arise from genuinely different points of view that in a democracy require proper consideration.

Despite its shortcomings the British planning system is one of the fairest and least corrupt in the world. Where skilfully handled it is capable of bringing a high degree of subtlety to urban development through the negotiation of bespoke solutions that respond to complex and contested issues. Here some notable ‘enemies of enterprise’ give their own perspectives on the system.

Peter Rees, director of planning at the City of London (1987–2014). Major developments included Broadgate, St Mary Axe (the Gherkin), and 20 Fenchurch Street (the Walkie Talkie). Professor of city planning at The Bartlett School of Planning, University College London.

Rosemarie MacQueen, strategic director of built environment, City of Westminster (2007–14). Responsible for setting the planning and environmental policies in London’s West End. Oversaw the preservation of 11,000 listed buildings, the redesign of Leicester Square, and the regeneration of Victoria.

Pat Hayes, director of environment and planning at the London Borough of Ealing. Major projects include the regeneration of Ealing town centre, Old Oak Common and Park Royal.

The Role of Politicians

Councillors, the elected representatives of their communities, are ultimately the decision-makers in planning. They have responsibility for granting planning consent or refusal, but have to operate within national and regional planning policy guidance. Most major authorities are organised along party political lines and decision-making takes place through a cabinet style system of senior portfolio holders from the controlling political party. Operational decisions around, for example, licensing or planning applications are usually devolved to subcommittees.

The local councillor is in daily contact with

his or her electorate. Responding effectively to local issues is a key to political survival where electoral turnout is usually low and a safe seat might have a majority of just a hundred votes. Being a councillor can be a rather thankless and poorly remunerated task. The role attracts the politically ambitious who see their local council as a stepping-stone to higher office, as well as community campaigners, who may have a single political agenda. Sometimes it attracts mavericks and the deranged.

By and large, though, the role attracts some extraordinarily selfless individuals who genuinely believe in serving their communities. The system is democratic, representative and ultimately accountable and the work of local councillors is often overlooked. To voluntarily take on the responsibility for managing a local council and be able to get to grips with a whole range of technical issues is remarkable. Most metropolitan authorities and London boroughs have a turnover that would place them in the FTSE 100 if they were private enterprises. Three of these individuals explain why they do it.

Daniel Moylan, Conservative councillor at Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, deputy chairman of Transport for London (2008–12). Championed the improvements to Exhibition Road and Kensington High Street. Chaired the mayor of London’s Design Advisory Panel.

Steve Hitchins, leader of Islington council (2000–06), now chair of the Camden and Islington Primary Care Trust.

Sir Robin Wales, leader (1995–2002) and mayor of London Borough of Newham since 2002. During his leadership he championed the regeneration of Stratford around the London Olympics, and the Royal Docks.

The Development Sector

There is a common public image of developers as wealthy and venal, triggering gentrification, displacing communities and riding roughshod over democratic debate. Although this might well apply to some in the industry, as in all generalisations it is inaccurate. Developers are the instrument of change in cities. They channel investment, renewing and remodelling obsolete infrastructure, neighbourhoods and buildings. They create new places, housing, workplaces and public spaces. A city without development is static or dying, as London nearly found out in the

property crash of 2008–09. Developers come in all sorts of guises from the lone operator, often like a Broadway impresario, to large corporate concerns, independent and quoted on the stock market. There are bad developers that aim to maximise short-term returns regardless of long-term consequences, and there are the good developers who are instrumental in shaping the city for the better. Here are personal perspectives from some of the good developers operating in London today.

Adrian Penfold, head of planning at British Land. Major London developments include Regent’s Place; the Leadenhall Building (Cheesegrater); refurbishment and extensions to Broadgate.

Alan Leibowitz, joint managing director, Dorrington Properties, a development and property investment company with a portfolio of over £1.6 billion, comprising offices, commercial and residential properties in London and the south-east.

Sir Stuart Lipton, developer, Lipton Rogers Developments (previously Rosehaugh Stanhope and Chelsfield). Major schemes include Broadgate, Chiswick Park, Paternoster Square, the Commonwealth Institute and the Royal Opera House.

Community Involvement and the Mistrust of Planning

Today’s society is considerably more pluralistic and fragmented than when the planning acts were formulated in the 1940s. Planners and politicians are seen as increasingly remote and communities are less willing to accept a series of solutions imposed for the public good. From the 1960s, opposition to excesses of road building, property speculation and the wholesale clearance of neighbourhoods led to an increasing demand for democratic debate on the future of neighbourhoods and their communities. Public consultation has become a statutory requirement within mainstream planning, and successive governments have taken action to strengthen citizens’ rights within the system. Wider consultation does, however, sit uncomfortably with the desire to speed up the decision-making process.

The growth of public involvement has coincided with a significant reduction in the power of local authorities as fiscal control has become tighter and ever more centralised. The technical nature of the planning system has also increased to the point where it is difficult for the public to understand it, let alone participate in its workings. Local plans tend to be long, technical and often dull policy documents, of little obvious relevance to the communities that they are meant to serve.

Although the system is flexible and open to interpretation and debate, the organisations that administer the process, local planning authorities, have often lost the confidence of their citizens. The fragmentation of political consensus has led to the emergence of an important third voice in the process. Well-organised communities can play a vital role in challenging and enriching the debate. At one end of the spectrum are NIMBYs,10 simply seeking to protect their interests; at the other end are articulate and skilful individuals and organisations that have had a fundamental influence on their immediate and wider communities. Here are the views of two of them.

Lorraine Hart, director, Community Land Use, an organisation that supports community-led development and regeneration.

Dominic Ellison, chief executive, Hackney Cooperative Developments CIC (Community Interest Company).

In the following chapters we attempt to dissect this political process and describe how it works in practice. But development is not an abstract exercise. Sites have histories and contexts and these also frame the possibilities for the future. A failure to understand context is possibly one of the most damaging mistakes a developer can make. Organisations also have histories. In the words of Alison Lowton, former borough solicitor at Camden council, ‘one of the odd things about planning is that things go on long after they have happened’.11 In the next chapter we look at the history of King’s Cross.