5.

The Masterplan

The King’s Cross masterplan sets out the relationship between the buildings and the spaces between them, the through routes and internal circulation, built form and heights and the disposition of land uses. It was the key document that set the spatial context for the negotiations and against which questions such as the quantum of floor space, the quality and accessibility of public space and the scale and location of particular buildings were tested.

Both the Argent and Camden council teams spent a great deal of time working with the architects on the masterplan, and the plan was shaped by that debate. The masterplan evolved over the first two years of the development and it continued to be refined right up to the end of 2005. Two architectural and one landscape practice were involved in the production of the masterplan, as were Argent, Camden council planners and English Heritage. As the masterplan was so entwined with negotiations, it is considered here in a separate chapter. Many of the key objectives, such as wider economic and social regeneration, links to surrounding areas and management of the public realm could only be resolved through the masterplan. As an important element of the plan was the setting and reuse of the historic buildings, heritage issues are also considered in this chapter.

The Role of the Masterplan

Masterplanning is a term, often applied too loosely, to describe any large scale development framework, planning strategy or architectural vision. Masterplans are generally prescriptive and illustrate what an area will look like at a particular time in the future. The problem is that the future is seldom easy to predict, let alone prescribe. To have a plan is one thing, to achieve it is another. The process of implementation, often over a protracted period, requires either a high degree of control or a great deal of flexibility. In order to plan and execute a large development, control is needed over land, finances and all the regulatory consents (and variations thereupon) over a prolonged period. To add to the challenge there are external forces over which there is little control, such as business cycles, changing political and planning frameworks, the impact of new technologies and fluctuations in the property market. A good masterplan needs to be robust enough to cope with all of these. As it turned out, the property crash of 2008 provided an extreme test of its strategy, one that the masterplan did indeed pass.

At King’s Cross, Argent St George had control over the land and access to finance, two of the basic requirements to undertake development. One of the central roles of the masterplan therefore was to provide a framework for securing the third requirement, planning consents. The masterplan had to:

- show Camden’s planners what the project would look like on completion, including its mix of uses, environmental impact and range of local facilities

- show Argent St George the different intermediate states and demonstrate it could be built and let in different phases in response to market conditions

- convince institutional investors by showing a feasible long-term vision for the site with the flexibility to adapt and renew itself over a long period of time.

An effective masterplan responds to the complexity of the site conditions. It articulates simple and legible hierarchies and relationships between buildings, streets and spaces, and provides a structure and order that allows a wide variety of different architectural styles to be incorporated. This is inevitably a subtle process. The optimisation of the shape and size of individual building plots needs to be balanced against the quality and complexity of the spaces around them. A masterplan needs to understand the conditions on its edges, and wherever possible facilitate rather than inhibit future changes that might occur in the surrounding area. These tensions lie at the heart of good masterplanning. In short, it is part of an open-ended process, a conversation through which the city evolves.

A good masterplan will allow individual buildings a degree of independence from their underpinning infrastructure. This flexibility allows a scheme to be built out in a variety of ways depending on market conditions. In the longer term it will also allow for the eventual renewal and redevelopment of individual parts of the area. The test of a good masterplan is its ability to endure and to remain a relevant element in the continuing evolution of the city. Many of the rules are relatively simple and can be found in historical precedents, such as different geometries, building forms, scales and relationships. Masterplans based on theoretical and abstract geometries that fail to respect the context of the surrounding city tend to be inflexible and potentially sterile.

The Masterplanning Team

Unusually, Argent St George appointed two masterplanning teams, Allies and Morrison and Porphyrios Associates, together with Townshend Landscape Architects. Argent had worked with both teams on the Brindleyplace development, and although they had quite different approaches to architectural design, their thinking on masterplanning was complementary and mutually challenging. One of the unusual features of the arrangement was that the landscape architects were commissioned at the start of the process, and were able to contribute to the early debates about the arrangement and use of space and circulation in the scheme.

Bob Allies and Graham Morrison shared an interest in the subordinate relationship of buildings to the space that surrounds them; how buildings enclose space, and how this in turn influences the experience of the city. Their practice had developed a refined and understated modernist style and by the 1990s they had completed a series of major commercial buildings and masterplans. The work of Demetri Porphyrios, ‘classicism is not a style’,1 reflected his profound understanding of the European architectural and urban planning tradition from the Greco-Roman period to 20th-century modernism.

The critical question was how to masterplan such a large and complex site. All the practices were interested in the constraints imposed by the stations, rail infrastructure and historical fabric, and by the barriers that separated King’s Cross from the surrounding area. They recognised that the masterplan had to be subservient and responsive to context.

Site Context

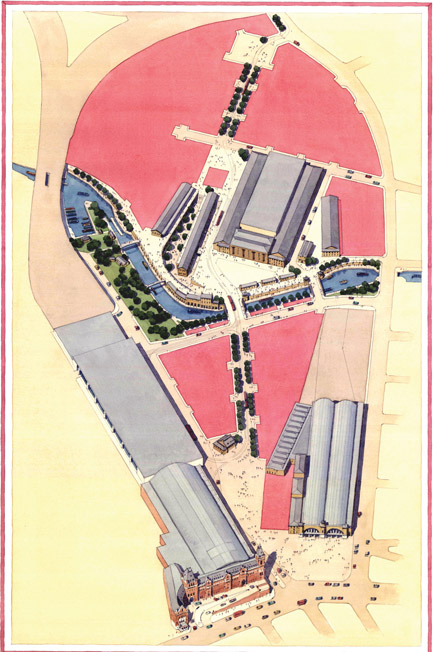

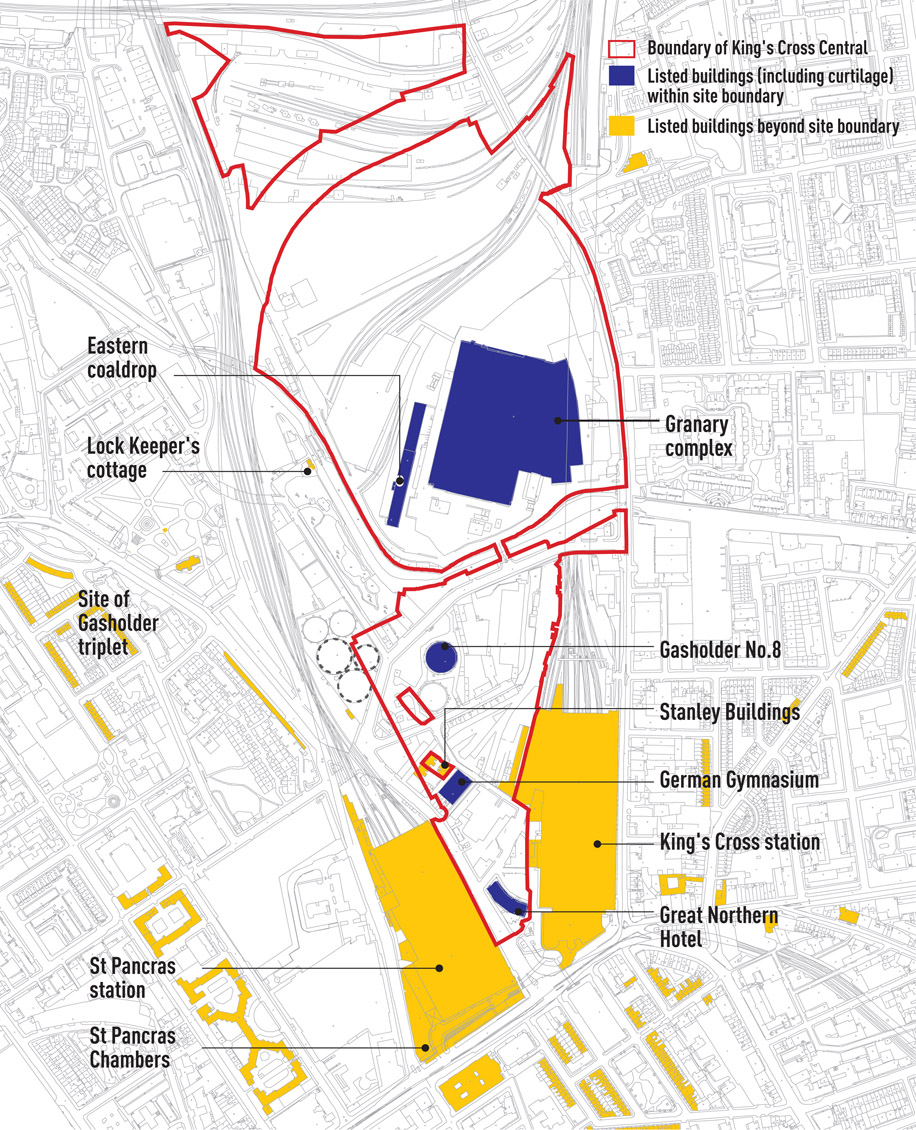

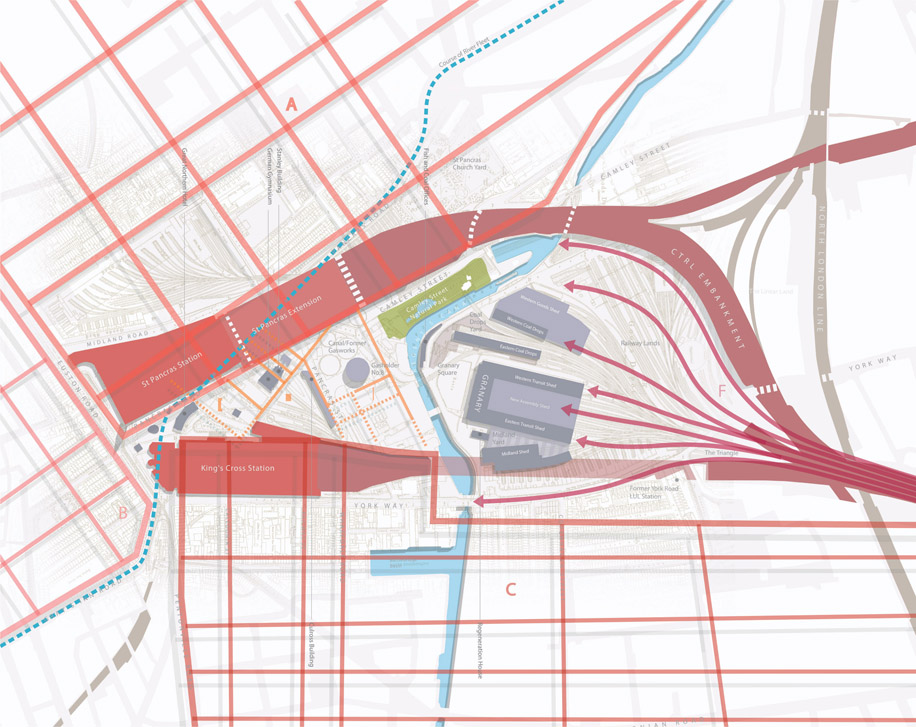

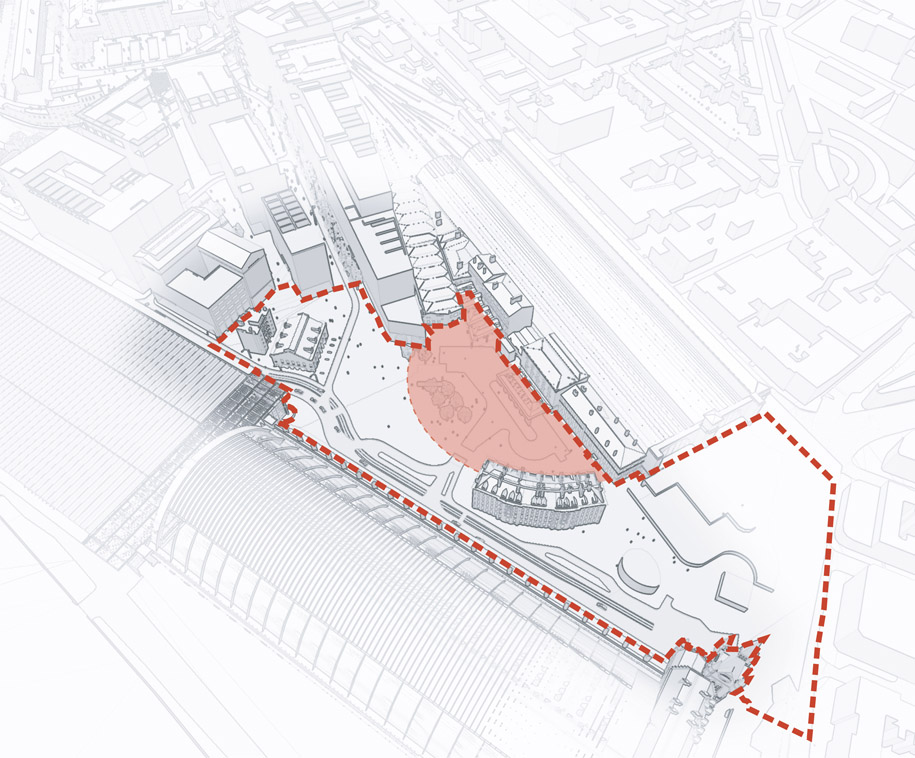

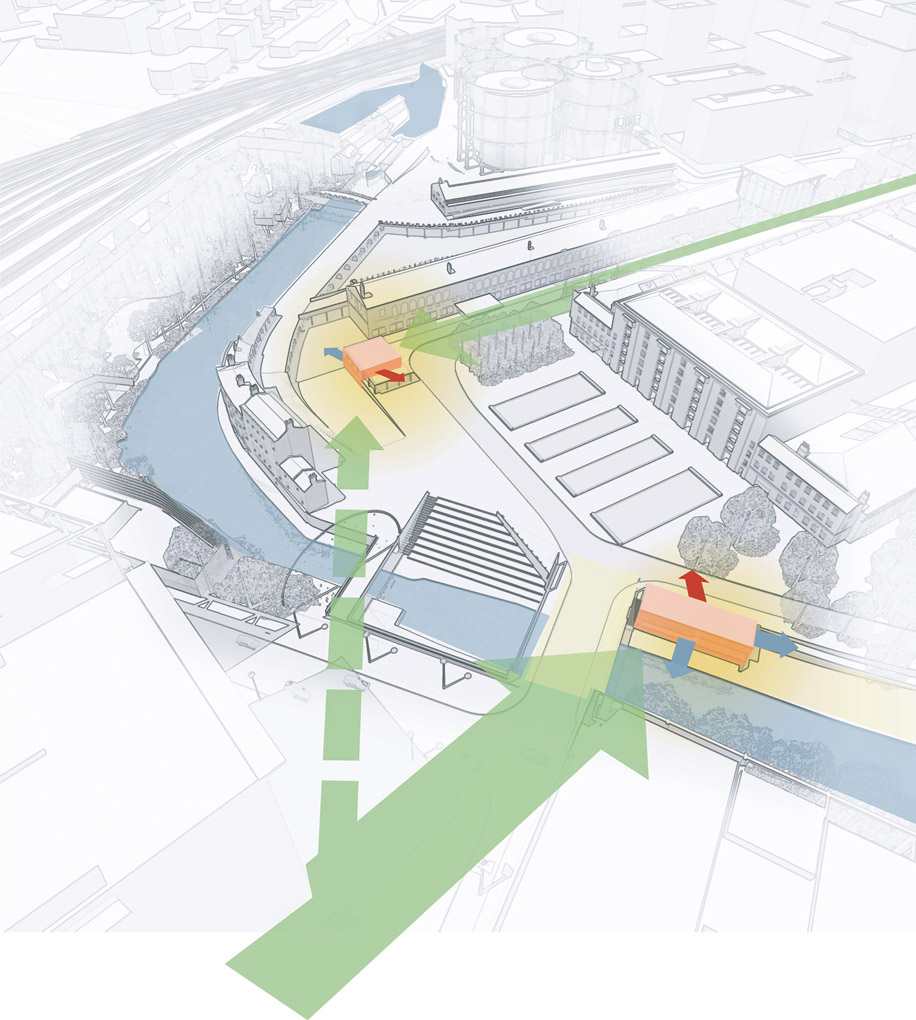

Figure 5.1:

Axonometric showing main historic buildings (note: the Great Northern Hotel does not appear on this diagram).

Over a kilometre long from north to south, the King’s Cross site rises by almost 10 metres to the Regent’s Canal – which divides it at its centre – is covered by two conservation areas and contains an important collection of historic buildings and industrial archaeology (Figures 5.1 and 5.2). In the southern part of the site a group of buildings of international, historical and architectural importance reflect the power of the Victorian railway age. King’s Cross station (1852) and the Great Northern Hotel (1854), both designed by Thomas Cubitt in a restrained Italianate style, contrast with the Gothic Revival style of St Pancras station (1865–68) designed by William Barlow and St Pancras Chambers (1868) by George Gilbert Scott (see Figures 3.5 and 3.6 on p.21). Between the stations the German Gymnasium (1864–65) is important to the history of the gymnastic movement, and Stanley Buildings North and South (1864–65), are examples of philanthropic housing for workers. Further north stood the unlisted terrace of Culross Buildings and Culross Hall (1891–92) and the Grade II-listed No 8 Gasholder (1883). The unique triplet gasholder had already been dismantled and stored to make way for the extension of St Pancras Station, but with an agreement that it would be reconstructed in a location elsewhere within the site.

The Regent’s Canal, completed in 1820, predates the development of the site and provides a focus for a second group of historic buildings – robust warehouses and storage buildings that fan out from the railway sidings that previously serviced them. The centrepieces of this group are the Grade II-listed Granary Building (1851) and Regeneration House, also by Cubitt (see Figure 3.7 on p.22). Originally, a basin existed in the front of the Granary Building, allowing the trans-shipment of goods between the canal and the railway. Two buildings flank the Granary Building with long sheds behind them (the Eastern and Western Transit Sheds). Behind this are other listed railway buildings, dating from 1850–88. The Fish and Coal is a curved range of offices from 1851–60s, overlooking the canal, while completing this group are the

long structures of the Eastern and Western coaldrops. Together they form a historically important group of buildings that enclose a series of spaces containing a rich selection of industrial artefacts such as railway lines, bollards and granite setts. Opposite, on the other side of the canal is the two acre Camley Street Natural Park, owned by Camden council and leased to the London Wildlife Trust.2 Camden council recognised that any interference with this popular facility would be too contentious to contemplate, given mayor Ken Livingstone’s ardent support of the park.

Early Discussions

The preliminary stage in the preparation of the plan was a two-day design seminar organised by Argent St George, bringing together Allies and Morrison, Townshends and Porphyrios Associates with engineers, environmental consultants and planners. Each party outlined the main influences on their own work and considered exemplars that might inform designs for King’s Cross. The objective was to develop ‘a visual vocabulary of urban designs and urban schemes’.3 The presentations provide an insight into the depth of theory underpinning the eventual masterplan.

Demetri Porphyrios started the session with a master class on the history of 19th- and 20th-century urbanism. This ranged from Hippodamus’ 5th–4th century BC military base at Miletus (regarded as the first recognisable masterplan), to Priene, Athens and Assos (the visual composition of space) and Pergamon (the use of monumental architecture). He went on to consider the development of the plan for the Roman town, its survival and adaptation in medieval and renaissance Italy, Ledoux’s enlightened town of production (Chaux) and Berlin’s use of building codes and the reinterpretation of axial routes. He contrasted London to all these examples as ‘a collection of major buildings and villages’, a city that had ‘resisted monumentality’.4 Porphyrios developed the argument of the differences between London and its European neighbours by looking at Paris under Haussmann, and Barcelona under Cerdà. He also contrasted the almost anti-urban theories of Ebenezer Howard with the work of Le Corbusier, ‘the most brilliant architect; the most awful urbanist’.5 He ended with a critique of post-modernism.

His introduction is outlined here because it set the tone for the debate about the very nature of the place that King’s Cross might become. It was not about a sterile argument between modernism and classicism, but a debate about the urban plan (framework) as opposed to the building. Therefore the right plan could accommodate a variety of architectural styles, both now and in the future. Importantly, his illustration of the concept of the public route and its relationship to civic buildings laid down the central spine of the future masterplan (the Boulevard’s critical relationship with the Granary). Furthermore, through application of the principles of the Nolli plan,6 Porphyrios argued that the historic buildings on the site could be embedded into a new urban fabric, as opposed to preservation devoid of context (as in the earlier Foster plan).

The second session, led by Jason Prior of the landscape architects EDAW, focused on the morphology of urban spaces. It looked at the ways in which a hierarchy of routes and spaces could assist orientation and create character. He considered the importance of climate and how spaces work at all times of the day and night. Prior concluded that ‘design is not a spray-on, it can not be retrofitted (into a masterplan)’.7 The group looked at comparable projects elsewhere, including Canary Wharf, ‘the office ghetto’; Eurolille ‘radical new’; Covent Garden, ‘evolution in action’; and Mayfair, ‘the highest rents in the country (so obviously doing something right)’.8 For all these examples, plot ratios, transport, public realm and the mix of uses were analysed and a range of simple design parameters were discussed. These included creating destinations, scale, sequence of spaces, design guidance, active ground floor uses, hours of use, access and choice of access, ability to evolve over time, diversity and flexibility, integrated sustainability and long-term management. These ideas were not radical, but importantly, the whole professional team and Argent St George had derived them collectively, owned them, understood their implications and were willing to apply them throughout the process. Argent’s David Partridge said subsequently, that the seminar was about ‘manufacturing a consensus’ between the design teams and Argent St George.9

The First Masterplan

There were four starting propositions for the masterplan. The first was that the context for the masterplan was already set by the historic buildings, in particular St Pancras and King’s Cross stations. Their geometry would determine building relationships in what was essentially a triangular site south of the canal. North of the canal the site tapers, culminating in a second triangle. Here the predominant historic geometry was the railway sidings that splayed out away from the canal. The position of the buildings that they served was directly related to that geometry. The second proposition was a desire to preserve as many of the historic buildings as possible, not as historic artefacts, but embedded within a new urban form. The third proposition concerned the length of the site and the need for devices to draw people northwards from the station interchanges. The space in front of the Granary was viewed as the central public hub of the scheme. The fourth proposition reflected the difficulties of designing a new piece of city that was significantly severed from its surrounding neighbourhoods. In particular, the railway embankments to the west and north meant that although King’s Cross was within the political jurisdiction of Camden council, geographically it was part of Islington. The question of how the site could connect the two communities became one of the major considerations in the design.

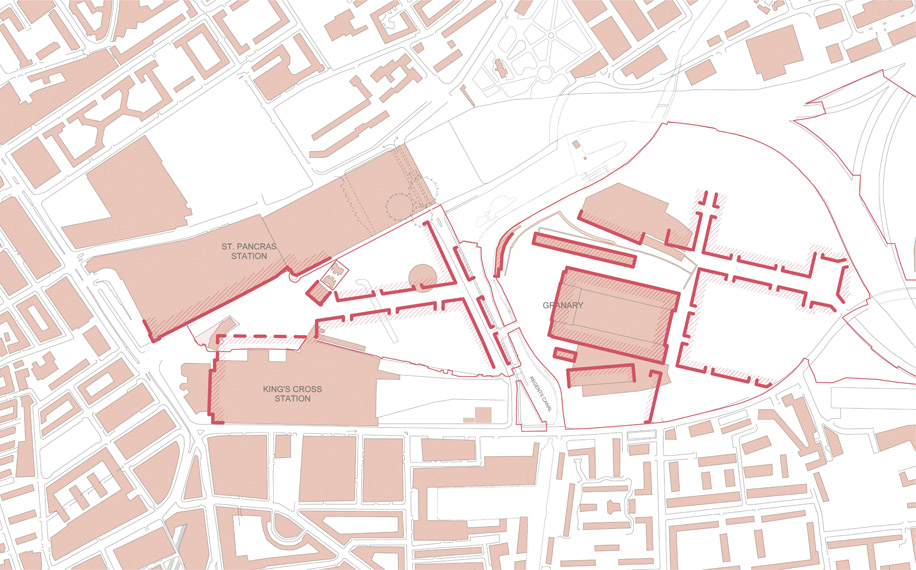

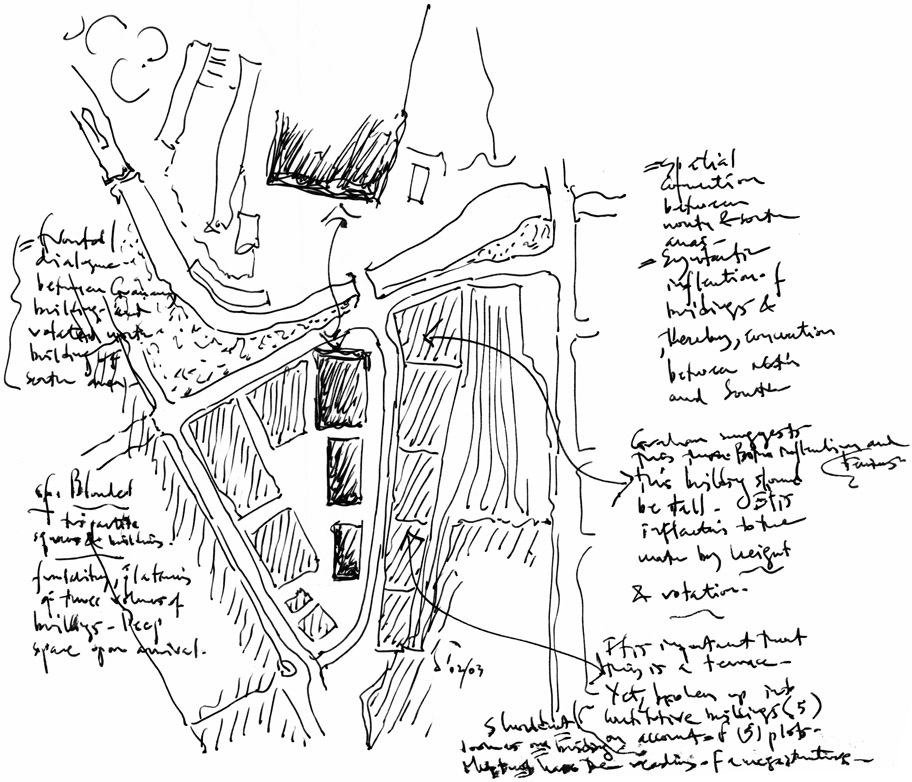

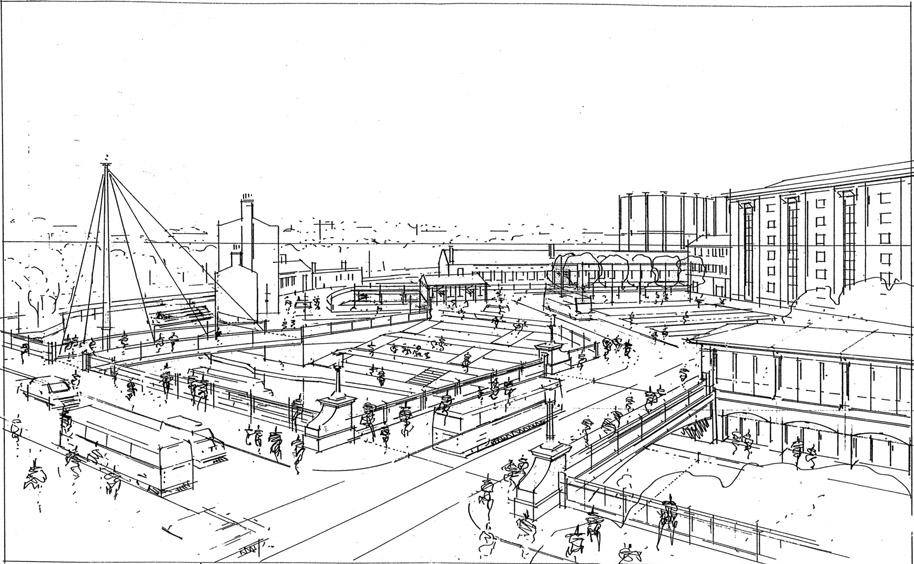

Figure 5.3: Early conceptual drawing showing central spine route.

Figure 5.4: Early development drawing showing notional streets and development parcels.

Argent St George, Camden council and the masterplanning team had already agreed that King’s Cross should be ‘just another piece of London’ and reflect the grain, scale and character of the city. The example of Canary Wharf was often cited in early discussions to illustrate a development outcome that would be inappropriate. In particular, it was agreed that the development should connect physically, socially and economically into the surrounding area and should have blurred rather than hard edges.

From these initial stakes, the team agreed the basic structure of the masterplan. The plan for King’s Cross was based on the idea of the ‘human city’, the principles of which are the long-term sustainability of the masterplan’s framework; maximum connectivity with the existing city; a physical urban plan with mid-rise high density buildings; and a plan that establishes a dialogue between public and private spaces. The Granary and the space in front of it would become the main focus for the central portion of the site. A simple connecting route or boulevard (civic route) would provide a spine running the length of the site (Figure 5.3). Its position would be determined by the requirement to optimise separate development parcels either side (Figure 5.4). The Granary provided both a destination and a focal point, and its position in the scheme determined the geometry of the north of the site, in particular by deflecting the central spine route westward before it eventually rejoined York Way at the top of the site. By extending the alignment of Copenhagen Street into the site, a simple division of the northern portion of the site was achieved with four development parcels (Figure 5.5). The precedent cited for the north-south route was Las Ramblas in Barcelona.

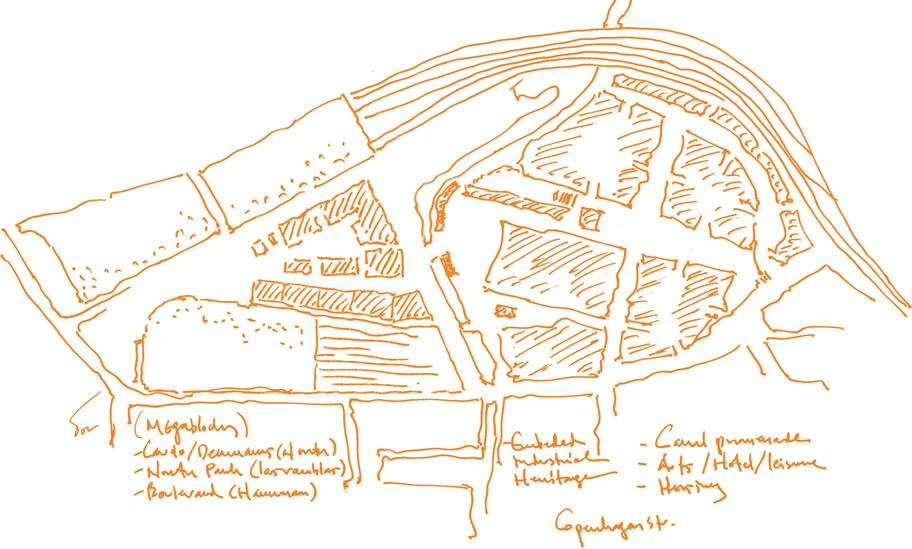

Figure 5.5: Early masterplan sketch showing links to Copenhagen Street and the Boulevard.

This simple plan gave a point of connection to the Islington street grid with crossroads at Copenhagen Street (Figure 5.6). It also set up the conditions for a variety of different development phases. But it was more subtly referenced than that. As seen in Figure 5.3, the spine route connected three new spaces, in the south between the two stations, in the centre in front of the Granary, and at the north on York Way. In the centre, the Granary acted as a ‘basilica’ or ‘cathedral’ with a piazza, and Porphyrios cited Blondel’s 1765 plan for Strasbourg as a precedent. The division of the northern part of the site into four quadrants roughly on a north-south, east-west axis resembled the Cardo Decumanus of the Roman city. The central hinge of the intersection north of the Granary would be marked by the park. At this stage in the design process it was assumed that the Great Northern Hotel would be demolished and a major new public space between the two stations would be created. The initial proposition was for this space to be framed by simple colonnaded buildings. The use of historical precedents was never meant to be literal or nostalgic; instead it allows a set of propositions to be tested, referenced and communicated. It is the interpretation and application of lessons that make them powerful tools. Straightforward replication can produce a theme park. The precedents, of which there were many in the King’s Cross masterplan, were used to begin, rather than end, the design process. From these initial concepts the masterplan went through many adjustments and refinements.

Figure 5.6: Masterplan in February 2002 prior to presentation to the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE).

Developing the Masterplan

The first refinement was to interrogate the orthogonal geometry set up by the principle routes. Regular grids have many advantages; they are legible and create standard sized building plots, optimal in terms of development economics. Much of central London is in fact grid based, but these grids are not uniform. The piecemeal development of the city in the 18th and 19th centuries meant that grids are usually offset, are of different proportions and do not align. In the areas adjoining King’s Cross there were three such grids aligned on different geometries.

The team concluded that a simple geometric grid referenced to the central space would be inappropriate. There were two principle reasons for this. The first was the difficulty posed by the retained listed buildings. These sat in relation to the geometry of the former railway sidings that had fanned out as they entered the site from the north (Figure 5.7). Forcing them into an orthogonal grid would, at best, create an uneasy relationship between them and new buildings, and at worse, leave them as objects detached from any urban context. Incorporating the geometry of the railway tracks into the masterplan resolved this problem, and introduced a degree of informality that allowed intervening spaces to be adapted in a more sophisticated manner (Figure 5.8). In particular, the widening of the spaces on the spine to the north of the Granary allowed a new public park (Long Park) to be created.

Figure 5.7: Conceptual drawing showing adjoining street grids and geometry of railway sidings.

The second reason stemmed from a deliberate decision to explore the use of perspective to inform the pedestrian experience of the site. By widening the Boulevard as it approached the Granary, perspective could be manipulated and the distance appear foreshortened. It also created a more efficient geometry for the adjacent development parcels. To the north of the Granary the reverse takes place; the buildings converge, effectively lengthening the perspective and emphasising the size and proportions of the public spaces (Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.8: Working development sketch.

Notes from top left: 1) Frontal dialogue between Granary Building and rotated north of building of south area; 2) CF Blondel – tripartite squares and buildings, functionality of three volumes of buildings. Deep square upon arrival; 3) It is important that this is a broken terrace. Yet, broken up into buildings (5) on account of (5) plots. Should not look as one building. Must not have the reading of a megastructure; 4) Graham (Morrison) suggests this building should be tall. Inflection to the north by height & rotation; 5) Spatial connection between north and south areas. =Syntactic inflection of buildings & thereby connection between north and south. (Taken directly from Demetri’s notes on the drawings.)

Scale and building heights

With the basic framework in place, the masterplanning team could start to consider scale.10 The question of what constitutes a human scale is vexed. The centre of most European cities, including London, was developed with traditional load-bearing structures, and the resulting scale tends to be four to six stories. Within and between buildings, land uses are mixed (as opposed to being rigidly zoned) and the urban form is both complex and comfortable in its familiarity. The building technologies of the 20th century have challenged these premises, along with the automobile and increasingly specialist requirements of present day commercial buildings. New urban forms have emerged that pose challenges to today’s designers.

The two-day design seminars had already agreed that the mayor’s advocacy of tall buildings (see p.63 in Chapter 4) might be in conflict with the scale of the emerging masterplan. Argent did not support tall buildings, believing them to be a risky commercial proposition. It considered 10–12 storeys to be the optimum, as it could be let to a single office tenant and optimised building costs. Above a certain height, structural costs increase and floor plates diminish. Ten to 12-storey buildings were also easier to fit into a conventional street-based masterplan. The King’s Cross site sat within viewing corridors from Parliament Hill and Hampstead Heath to St Paul’s Cathedral and long-established planning policies restricted the height of buildings within these corridors. These were firmly embedded in the mayor’s own London Plan. Although the mayor had offered to ignore these policies,11 Argent St George was content to comply with them, and a prevailing 10–12-storey height was incorporated over most of the site.

Design review

The first masterplan was largely in its final form by the beginning of 2002 and Camden council was mostly satisfied with progress. The decision was made to take it for design review by the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE). CABE had been set up by the government as an independent organisation to promote good design in the built environment and was well-regarded and powerful. Its views were non-statutory but carried considerable weight. The first design review took place in February 2002. While CABE acknowledged the thoroughness of the approach, it was critical of the emerging masterplan:

The letter went on to say that while the routes through the site were anchored well enough in the south they were not adequately resolved to the north and east, particularly around York Way: ‘[…] the proposed grids do not seem to derive from anything in particular’. Regarding the open spaces, CABE suggested that greater consideration was needed concerning ‘what each is for, and what is the appropriate size for it. In some cases, the spaces proposed seem too large, so that it may not be possible to achieve

Figure 5.9: Masterplan development sketch showing exaggerated perspectives.

the life and activity hoped for.’ CABE’s summary was damning:

In March 2002 the plan was also taken to English Heritage’s London advisory committee. The committee was a key statutory consultee in the planning process, and its support was essential. Its response was to: ‘[…] applaud your approach […] the analysis of the area’s history, architecture, urban characteristics and heritage significance has been exemplary’.13 However, English Heritage had concerns over the loss of a number of listed buildings and the incorporation and setting of others within the masterplan. It expressed particular concern on the unresolved nature of the southern part of the site and its failure to ‘consolidate the frayed urban fabric in this area’. It delivered a clear note of opposition regarding the proposed demolition of listed buildings in this area, in particular the Great Northern Hotel.14

Refinement of the Masterplan

CABE’s comments were met with a degree of shock by Camden council and the project team. There was some suspicion that CABE had an innate bias in favour of a modernist rather than traditional approach to masterplanning and that it had failed to understand the scheme. There were however, clear and important messages from both CABE’s and English Heritage’s responses. A project of this complexity needs to go through a number of iterations. The scheme presented, although fundamentally sound in its research and intentions, was still only partly formed. In Graham Morrison’s words, ‘it was the last 10 per cent of the design development, to make the plan work, that occupied most of the remaining time’.15 It was not that the masterplan was poor, it was more a case that it could have been better. Design review plays an important role in the evolution of schemes. It is an external challenge, and when the parties believe they have done enough, it forces a critical rethink.

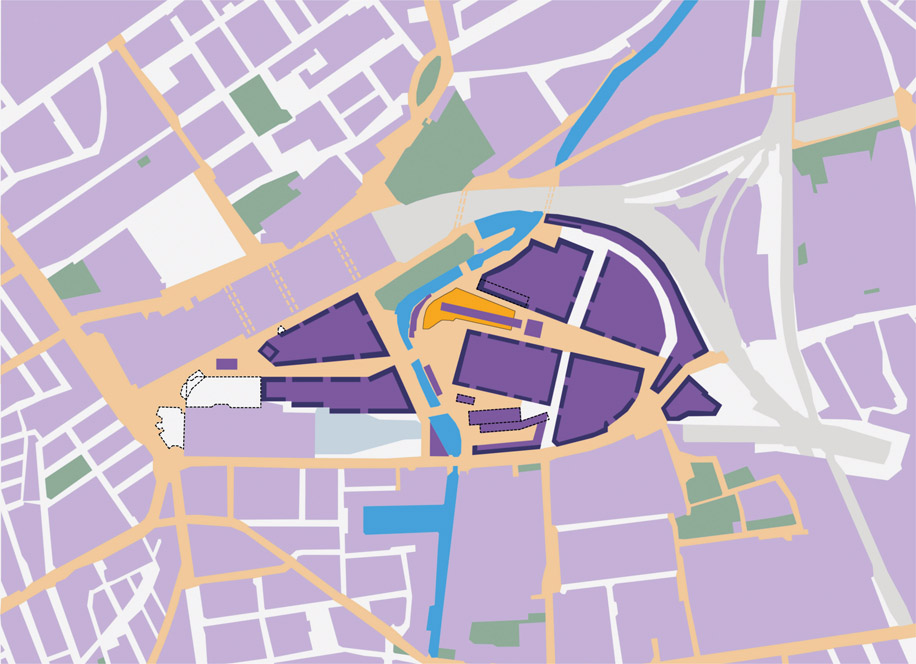

The design team reconsidered the plan, particularly the concern that the initial plan was too rigid. First, the scale, grain and size of individual development parcels were reviewed. Initially Porphyrios suggested that the grain should be broken down into a series of far smaller buildings within larger street blocks (Figure 5.10). He argued that the very objective that King’s Cross should be ‘just another piece of London’ supported a very fine grain with significant variations in heights from one building to another. Allies and Morrison advocated a different approach based on the requirement to achieve street blocks better tailored to commercial needs. Further development between the teams arrived at a compromise where the mega blocks were retained but were divided by streets that allowed smaller buildings to be accommodated (Figure 5.11).

Figure 5.10: Refinement of masterplan into network of street blocks.

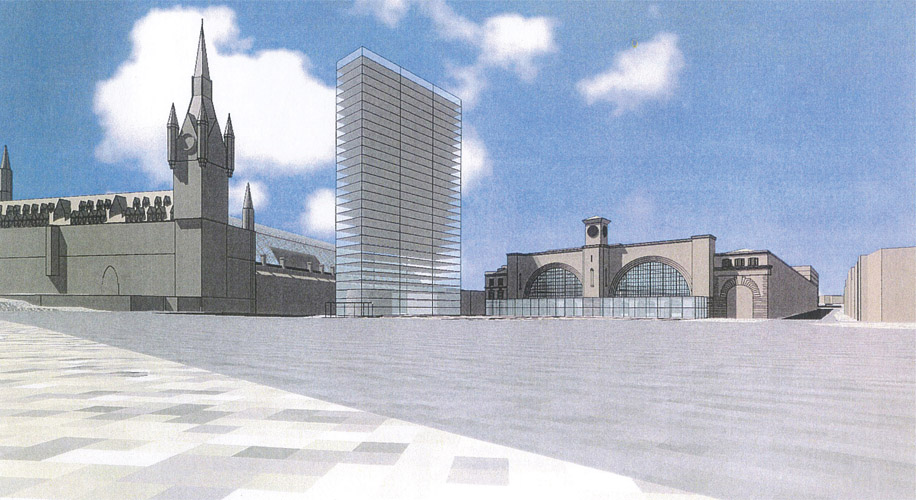

The Great Northern Hotel

The future of the Great Northern Hotel still had to be resolved. Although Argent St George and Camden council recognised its importance, the Grade II-listed structure was in poor condition and formed a serious bottleneck between the stations at exactly the point that the taxi and bus stops should be. Moreover, TfL’s aspirations for segregated bus and cycle lanes would occupy the entire space, and pedestrian movement along Pancras Way would be impossible. Although it was clear that English Heritage would oppose the loss of the Great Northern Hotel, both Camden council and Argent St George were convinced that its demolition would open up opportunities for a far better resolution of the southern part of the scheme and a new concourse for King’s Cross station. It was, they surmised, what the Victorians would have done. Various studies were carried out, including the construction of a glass station box alongside King’s Cross and even the positioning of a tall building between the stations (Figure 5.12). The removal of the hotel would, however, have left a poorly defined space around the front and side of King’s Cross station, which would have been filled with taxis, bus canopies and all the paraphernalia associated with transport operators. Although the responsibility for a new concourse for King’s Cross rested with Network Rail, and their architect John McAslan, the land upon which it was to sit had been transferred to London and Continental Railways as part of the development agreement. Camden council brought together the teams to ensure an integrated solution was found.

Figure 5.11: Revised masterplan (August 2002) following CABE and English Heritage comments.

(Major changes include repositioning of the Boulevard, reinstatement of the gasholders in new position next to canal and inclusion of larger public spaces.)

Although the constraints posed by the underground concourses were significant, McAslan proposed using the curved façade of the Great Northern Hotel to determine the geometry of a new curved concourse roof that rested above the colonnaded ground floor of the hotel (see Chapter 9). The decision to retain the Great Northern Hotel satisfactorily resolved the southern part of the scheme, accommodated TfL’s transport requirements and removed the significant threat of opposition from English Heritage (Figure 5.13). The southern space would be divided into two, each with clear and distinct functions. The southern space on Euston Road (later designed by Stanton Williams) is a city square providing a formal setting for the newly revealed frontage of King’s Cross station. It unites a group of outstanding, if stylistically different, grand Victorian buildings. The space to the north, in contrast, is a functional interchange framed by the two new station concourse buildings (see Chapter 9). This forms a natural and legible entrance to the Boulevard. Once the issue of the Great Northern Hotel had been resolved, the southern part of the masterplan could be finalised.

The Culross and Stanley Buildings

The Culross Buildings were built in the 1890s as workers’ housing by the Great Northern Railway. This simple four-storey terrace crossed the route of the Boulevard in the centre of the site. Although not listed, they were considered of local importance, despite the group of which they had once been a part having largely disappeared. To the south were the two Stanley Buildings, again workers’ tenements, but slightly earlier and more ornate, meriting a Grade-II listing.

Peter Freeman had already recognised that the Culross Buildings would pose significant design problems if they were to be retained, as they blocked the important visual link that the Boulevard would make between the stations and the Granary. They would also be extremely difficult to embed in the masterplan without significantly reducing the scale of the commercial development. Argent St George argued strongly that the Culross Buildings would jeopardise the development of the central part of the site and as they were not listed, advocated their demolition.

Figure 5.12:

Feasibility drawing for a tall building to replace the Great Northern Hotel.

The fate of the Culross Buildings (see Figure 5.14) became a cause célèbre for the scheme’s opponents. There was a strongly held view among conservation groups that the buildings were a key part of the overall assemblage of heritage structures and should be retained. Several local and national groups supported an alternative scheme for the Culross Buildings proposed by the King’s Cross Conservation Area Advisory Committee (KXCAAC). The committee argued strongly that the building should be preserved as residential accommodation and proposed cutting an arch through the structure so that, walking along the Boulevard through the Culross Buildings would be like entering a walled city.16 A small extension to the Culross Buildings was proposed to double the amount of residential accommodation, making it more viable and allowing the creation of a semi-public residential square.

Figure 5.13: Station concourse area, public realm and location of new concourse.

The fate of the Culross Buildings was seen by Camden council as having considerable potential to derail the entire scheme, as should

Figure 5.14: Design study showing the implications of retaining the Culross Buildings in relation to the Boulevard and proposed development blocks. Source: report by ARUP, April 2004.

English Heritage not be convinced that its demolition was unavoidable, it had the power to object to the development and therefore trigger a public inquiry. On the other hand, if Camden council had insisted on retaining the Culross Buildings, then Argent St George would probably also have gone to appeal. Camden council and Argent St George therefore went to considerable lengths in the masterplan process to examine different options for their retention. ARUP was commissioned to carry out a study, and its report in April 2004 examined options for retention but concluded that they should be demolished.17 This recommendation was accepted by Camden council and English Heritage.

Argent St George and Camden council favoured the retention of the southern Stanley Buildings but accepted that the straightening of Pancras Road, after the completion of Foster’s extension to St Pancras, was logical, but would necessitate demolition of the northern Stanley Buildings. The alternative of looping the road around them (and there was a temporary construction road in this position), would have left them as an isolated group, devoid of their original historical context.

The Boulevard

The blocks on either side of the Boulevard were designed around shared service basements and parking. On the western block seven commercial buildings were placed around a new triangular public space, St Pancras Square, thus effectively resolving the geometry between the Boulevard and St Pancras Way. The Boulevard was also moved eastwards to allow larger development footprints around St Pancras Square. On the eastern block four separate buildings were proposed.18 Beneath these would be a service yard, shared with Network Rail and accessed via a ramp from Goodsway. The final change was to realign the northern end of the Boulevard, turning the northern section to align with the front of the Granary.

In the centre of the site, in front of the Granary, a major new square would be the public centrepiece of the scheme, its proportions determined by the canal and surrounding historic buildings (Figure 5.15). The scale and dimensions of the square were carefully examined, and design exercises considered whether new structures might be incorporated, including a series of pavilions along the canal (Figure 5.16). In another design variation, Porphyrios proposed an elevated podium and promenade along Goodsway to resolve the topography of the site as it falls away to the west and reduce the apparent scale of the commercial buildings. His proposition was that the archways beneath would open up the basements for small

businesses, as in 19th-century railway viaducts, an idea that was not ultimately pursued.

The new square was always seen as the centrepiece for the scheme. Early ideas to restore the canal basin in front of the Granary were rejected in favour of a more traditional and lively public space. The key move by Townshends was to open the canal onto the square through the construction of a series of south-facing steps, a proposal originally criticised but now one of the most popular features of the scheme. The landscape strategy for the square had to strike a balance between the reuse of historic fabric and the creation of a new, useable public space, (Victorian granite steps might look good, but are an unsuitable surface for cyclists or people with disabilities). Townshend’s approach was to retain the historic fabric that had been part of the site, for example the railway lines, turntables and bollards, but to resist filling the spaces with historic bric-a-brac.

Back to design review

The revised scheme was taken back to CABE in July 2002. Although it was essentially the same masterplan, the design had matured and had acquired greater sensitivity both to its surroundings and to the historic buildings on the site. In particular, relatively subtle changes had been made in the geometry, not just in the realignment of the central boulevard but also in the relationship between the street grid and the buildings and spaces that it framed. This time CABE was more positive. Its letter states: ‘the committee offer warm support for the new direction in masterplanning’, while ironically referring to the ‘strength of the earlier framework’. In particular, CABE welcomed the further development work that had taken place around the canal and York Way. It put down a significant marker regarding the nature of the public realm:19 ‘it will be important to identify which of the roads are to be adopted by the local authority. The streets should foster a sense of citizenship and be accessible 24 hours a day […]. In our opinion, the Canary Wharf model, where the streets appear to be public but a private company controls access and monitors behaviour, is to be strongly resisted.’20 This point formed a significant part of negotiations with Camden council, as discussed in the next chapter.

Testing the masterplan

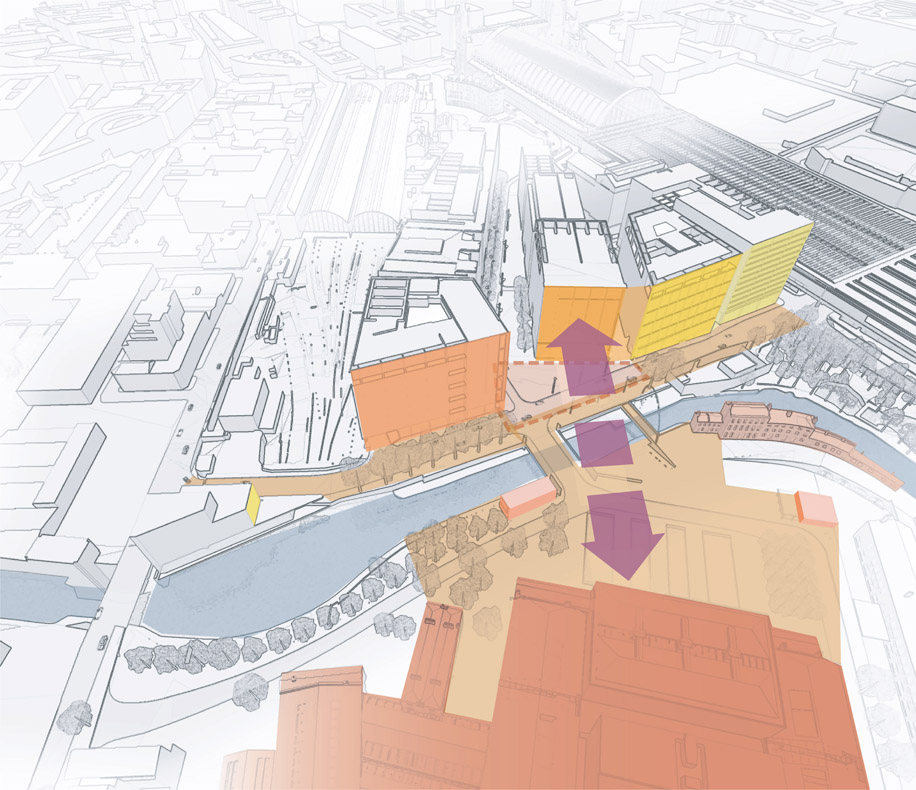

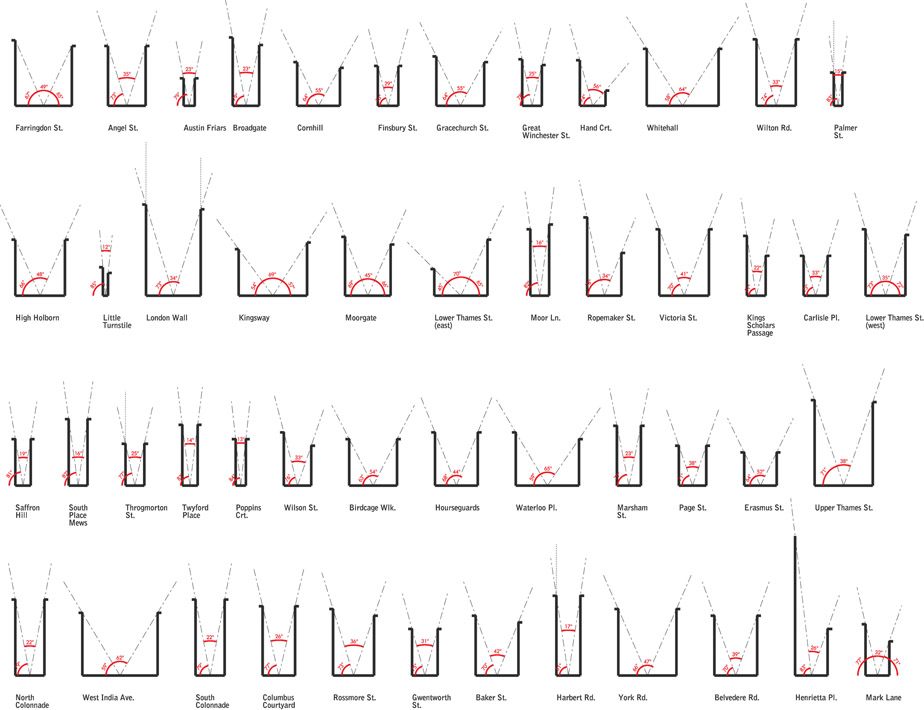

The next stage was to interrogate the masterplan in order to be certain that it could work in different permutations. Design exercises tested the relationships between each of the buildings and intervening spaces (Figure 5.17). Extensive design studies were carried using models, axonometrics, line drawings and watercolour renditions (Figures 5.18, 5.19 and 5.20). The proportions of streets and the dimensions of public spaces were also tested and referenced against comparable examples.

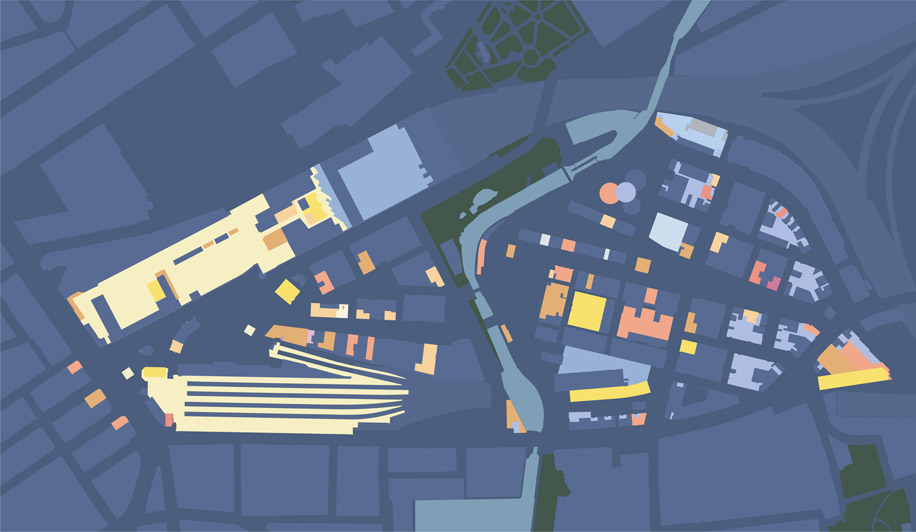

The final test of the masterplan concerned the notional positioning of appropriate land uses and activities on the ground floor frontages (Figure 5.21). There was always an intention that the whole site should be active, and if not the 24-hour city, it should at least be enjoyable, accessible, safe and stimulating through both day and night in all of its zones (Figure 5.22).

Linking the Plan to the Wider Area

Physical connections

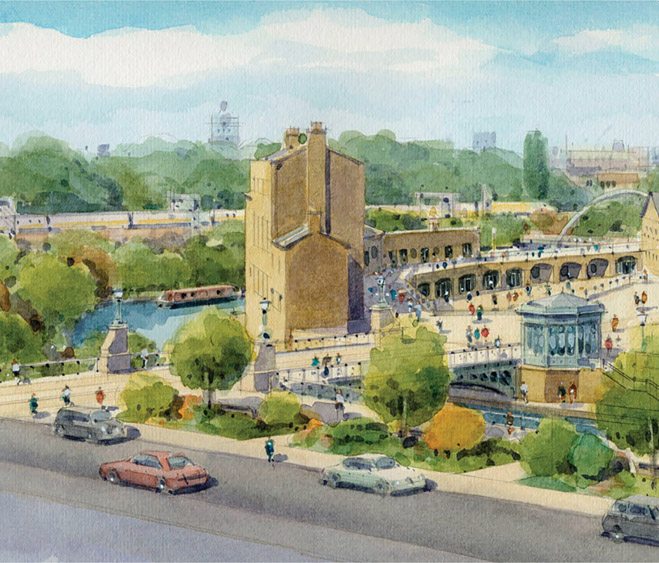

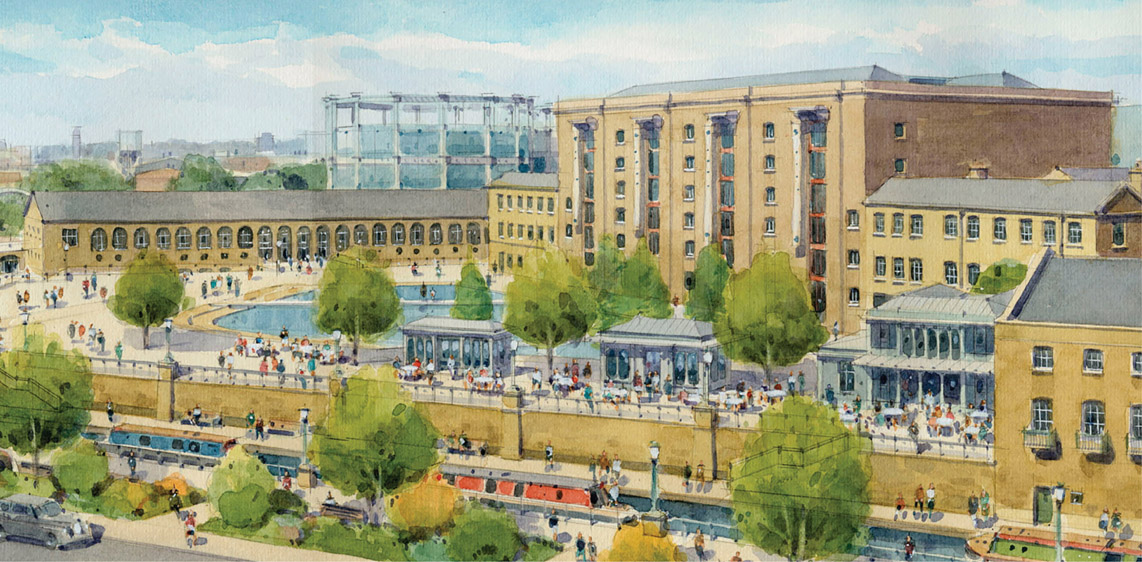

Figure 5.15:

CGI showing Granary Square.

Figure 5.16:

Same view of Granary Square – watercolour showing canal-side pavilions.

If King’s Cross was to be a seamless part of London, the masterplan had to connect to the wider area. Connecting the site to Islington in the east was difficult, as much of the historic urban structure had been destroyed by the 1960s housing renewal programmes. To the west, Goodsway was the only road connecting to Somers Town and physical integration was virtually impossible due to the railway embankments. The early stages of the masterplan had evaluated all the options to overcome the barrier of the tracks and Arup had been commissioned to look at options for bridges and tunnels. Bridging over the embankments was not feasible due to the sheer height problems. Tunnelling did not work either, as the canal passed under the railway and under that were the Thameslink rail tunnels. Any tunnelling option would have had to start and finish way beyond the site boundaries, effectively defeating its purpose.

Figure 5.17: Massing study on Granary Square and canal.

The final masterplan is shown in Figure 5.23. To the east, the masterplan proposed linking the King’s Cross road network directly into Copenhagen Street. To the south of this, the railway lines into King’s Cross station made further road connections unfeasible due to level differences. North of Copenhagen Street, though, there were opportunities as Islington council was in the process of restructuring the Bemerton estate. It would have been possible to connect streets from the northern part of King’s Cross through to Caledonian Road, in effect restoring the street grid that had been obliterated in the 1960s. Argent funded landscape architects EDAW21 to carry out a feasibility study, but the idea was never entertained by Islington council and a major opportunity was lost.

Psychological connections

Attention moved away from physical connections to consider devices to overcome the psychological barriers that might dissuade local people from entering the site. The idea was to make King’s Cross such an attractive destination that local people would see it as part of their own neighbourhood. Camden council and Argent St George analysed a range of factors that would impact on the experience of visiting King’s Cross, particularly how it could be made to look and feel familiar. Again, the example of Canary Wharf, with its hard impermeable edges, corporate urban realm and estate security was something all parties wanted to avoid. The critical issue of Camden council’s adoption and management of the urban realm is covered in Chapter 6, but these discussions laid down the basic condition that King’s Cross should be open and inclusive and should feel familiar to those living in surrounding areas.

Figure 5.18:

Drawing perspective of Granary Park.

Figure 5.19: Design study of Granary Square.

Figure 5.20: Comparative study of street scales.

To reinforce this concept, Camden council and Argent St George agreed that key buildings would be placed in specific locations within the masterplan. The public swimming pool and gym were sited at the end of Goodsway, as near to the western edge of the site as possible and at a prominent entry point. This location was further reinforced by Camden council’s subsequent decision to take a long lease on the entire corner building for their town hall offices. The primary school, nursery and health centre, however, were placed in the heart of the site, presupposing that unlike visits to sports facilities, which are voluntary journeys, walking children to school and visiting a GP are not. By placing these facilities deep in the heart of the scheme the idea was that these would become journeys of exploration and familiarisation. Granary Square and its fountains have subsequently become a popular destination for the wider community.

Figure 5.21: Final masterplan – rich mix of ground floor land uses.

Figure 5.22:

Night time economy.

Figure 5.23: Final masterplan.

Parks and open spaces

Despite some calls for a full sized football pitch, it was accepted that the site was just too small to accommodate leisure facilities on this scale. The concept of the London square was used as a familiar model to incorporate open space into the city. London’s Bryanston Square provided the model against which the size of spaces was tested, and Argyll Square provided a model for the blend of active, passive and children’s play that could be accommodated. It was agreed that formal spaces such as Granary and Pancras Squares would be important new civic spaces. Although these were to be managed by Argent St George, 24-hour public access was guaranteed, together with a commitment to manage as if they were publicly adopted.

Conclusions

A masterplan is not an abstract exercise; numerous commercial imperatives need to be embedded, building heights and plot sizes have to be optimised, and circulation and servicing

routes must work. David Partridge, managing partner of Argent St George, summed up a good masterplan as one that is legible: ‘it needs to have simplicity of navigation; it needs to have front doors. Without this legibility it will be extremely hard to sell properties to potential investors’.22 It is surprising how many masterplans fall at this first hurdle.

Without the ability to control land and finance, masterplanning can be a whimsical exercise. The masterplan must be able to guide development through implementation, and respond to changes in external conditions. It must be able to accommodate changes in phasing and be flexible enough to adapt to changes in the market. It needs to open up rather than close down future possibilities.

A good masterplan arises from a dialogue between an informed client, professionals within the team and the public at large. This takes time to develop. It also helps if this dialogue is based on a deep and scholarly understanding of design precedents and how to apply them. Research into the history of the area gives important clues to the potential urban form. Working with historic fabric and embedding this into new relationships is not easy, but it can produce distinctive places. Generally, the best masterplans are those that rise to the challenge of complexity.

Commissioning three practices to produce the masterplan avoided stylistic bias, and allowed time for a debate to take place and for the plan to mature. The three teams provided a creative tension, and ideas emerged from this dialogue that made the masterplan more subtle. The practices had a deep knowledge of the history and theory of architecture, landscape and city planning, and applied this to the challenges of the site. Inevitably, some architects have criticised the scheme. Zaha Hadid described it as dull and a missed opportunity.23 Others, such as architectural critic and journalist Rowan Moore, have been more complimentary.24 At the heart of this debate are the fundamentals regarding the nature of urban form. The masterplanning team opted for a particular form based on a legible street pattern. This does not necessarily make the scheme less radical.

The final masterplan developed over a period of more than four years. In reviewing its evolution, it is noteworthy that although aspects of its final form were clearly recognisable in its early stages, later changes, subtle as they were, resulted in significant improvements. Good masterplans are complex and display a deep understanding of their contexts. In contrast, masterplans based on abstract geometrics and parametrics struggle to produce good places.

The relationship between the masterplan and the historic buildings was central to the scheme. The historic fabric provided a constant challenge to the emerging design, but the strategy of embedding it into a new urban form, has resulted in buildings like the Granary sitting very naturally in relation to the new buildings and spaces that surround it. Paradoxically, it was the inability of the masterplan to embed the Culross and northern Stanley Buildings that led to the justification for their demolition. The tests of logic were exactly the same.

At the end of the day, one of the key tests of any masterplan is whether it gets built. King’s Cross is under construction and the plan has proved robust enough to adapt to extreme economic circumstances. It is too early to judge its success in creating a new piece of city; that will be up to future generations of Londoners.