8.

The Decision

By the autumn of 2005, negotiations between Camden council and Argent on the masterplan, the quantum of uses and the elements of the section 106 agreement were complete. In May 2004, Camden council received the planning applications for the King’s Cross site and these were subject to extensive public consultation. Following this, Argent reviewed its scheme and submitted revised applications in September 2005. After a further period of public consultation in October and November, Camden council was ready to determine the scheme.

Planning officers started to prepare a report and recommendation for the development control subcommittee meeting scheduled for two evenings on 8 and 9 March 2006. The report had to cover everything from housing numbers and tenure mix to cycle parking, archaeology, noise attenuation and the phasing of development. It also had to include a summary of all the feedback from the council’s consultation processes. It had to be exhaustive in order to demonstrate that every conceivable aspect of the scheme had been assessed and weighed against public comments and alternative options, so there could be no justification for a legal challenge or call-in by the mayor or central government. The final report amounted to just under 600 pages of text, in 19 chapters, and with 30 recommendations and 68 conditions. A separate report on the section 106 agreement was over 250 pages long. Both documents had been checked and double-checked, both by Camden council’s legal department and by external legal consultants.

The King’s Cross development was finally approved by just two votes. This chapter charts the way in which the slender majority in Camden council was achieved. It examines the problems that officers faced in trying to brief councillors on the development control subcommittee, considers the party political issues that influenced the voting, and the delicate balance in the roles of officers and councillors.

Camden’s Officer-Councillor Interface

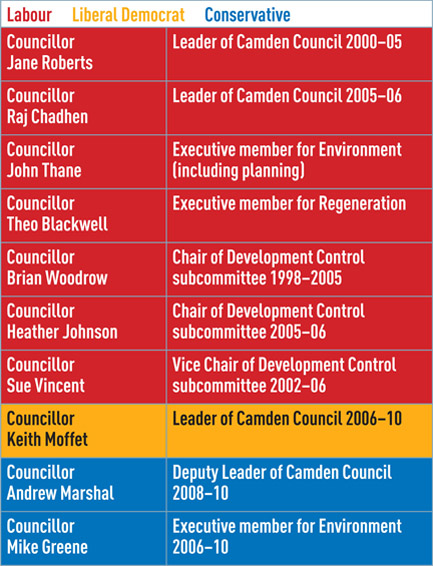

Under Jane Roberts, Camden council had built a strong collegiate corporate culture that was largely devoid of the officer/councillor mistrust that plagued many other councils at the time. There was an open process of debate on major issues through a series of regular officer/member corporate policy and advisory bodies (Chapter 4). The council leadership was briefed regularly and broadly supported the Argent scheme. The key councillors in relation to the King’s Cross application are shown in Table 8.1.

Camden council was a stable and well-run authority during the negotiation period (2000–06), with a Labour administration that appeared (falsely as it turned out) to be secure from challenge from the Conservative and Liberal Democrat opposition. Many of the councillors had been in office for long periods, but most had mellowed from the days of their radical youth. The leadership group under Jane Roberts while not exactly New Labour Blairites, were certainly in the political centre. The dynamics of a political party are however a complex mesh of personalities, histories and agendas.

While planning decisions (see the textbox below) may appear to be technical, in practice they are inherently political, and planning officers in the public sector are inevitably drawn into the political process. This is particularly true for senior personnel. A substantial part of the role of senior officers in a local authority is to manage the interface between the politicians and their particular department. That said, senior officers, as with government civil servants, are politically neutral and their posts should not be subject to the fortunes of a particular political administration.1

Decision-Making on Planning Applications

The UK planning system is described in Chapter 2. On major or controversial applications, decisions are made by a subcommittee of the council (usually called the development control subcommittee) comprising elected councillors, with the ruling party usually having a majority. That said, a development control subcommittee is quasi-judicial and should make decisions on the facts presented to them rather than along party lines. It is usual for the subcommittee to receive an officer report and recommendations on a development scheme in advance, and for this to be presented by the case officer. It may then hear representations from the applicant and any other interested groups or individuals before coming to a decision. It need not agree with the officer recommendation but should have sound (planning) grounds should it wish to go against it.

Senior officers walk a delicate tightrope in their relationship with councillors. To be effective, close working relationships have to be established with the senior councillors of the prevailing political party. Failure to do so can result in exclusion from key policy debates and may even lead to accusations of being obstructive. To be seen as too close, however, can raise suspicion from opposition councillors (in Camden’s case, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats) of political bias. On the other hand, to oppose councillors openly or covertly can be career threatening. Although there are clear rules to safeguard against the politicisation of local government, the looser controls at local level can be open to interpretation and roles can become blurred.2 Senior officers must take a clear political steer on issues but cannot overstep the line of professional neutrality. However, the line can become very indistinct where political priorities are unclear or where there is disagreement within the ruling party.

The Development Control Subcommittee

Camden’s development control subcommittee (the subcommittee) had a reputation for independence that sometimes bordered on the maverick. The problem had been going on for several years and both the borough solicitor and previous heads of planning had experienced difficult working relationships with the subcommittee. Anne Doherty, the head of planning, described it as the most legalistic committee she had ever come across. It viewed Camden council’s own planning staff with deep suspicion, and sought its own independent advice on several occasions. Officers were routinely accused of ‘expressing views’ by making recommendations about a scheme, and the subcommittee had, on occasion, overturned officer recommendations with no clear policy justification.3 Jane Roberts had concerns about the workings of the subcommittee. She wanted it to be proactive, less conservative and to focus on design quality rather than simply exercising a regulatory function. It was chaired by councillor Brian Woodrow, a veteran of battles to save Covent Garden and to stop the British Museum’s plans in the 1970s to demolish historic streets in Bloomsbury for a new British Library (see Chapter 4). Woodrow’s relationship with officers was far from easy. The problem was compounded by the fact that he had not spoken to Peter Bishop, his chief officer, for four years after Bishop’s refusal to recommend that Camden take enforcement action against the British Museum for using the wrong stone in the refurbishment of the Great Court.4

The problem of briefing the subcommittee

Councillor briefings are absolutely crucial for a development as substantial and complex as King’s Cross. While the leadership was regularly kept informed and was broadly in favour of the King’s Cross development (subject to a satisfactory deal being negotiated), councillor Woodrow seemed at best ambivalent. He refused to allow the subcommittee to be briefed, or to give any direction on negotiations during the entire six-year process. His grounds were that this would constitute bias and be contrary to the committee’s duty of independent decision-making. This view was not supported by the borough solicitor, the director or the head of planning. However, councillor Woodrow could not be dissuaded and refused all attempts by officers to brief the subcommittee.

The reality was in stark contrast to the way it was portrayed by the KXRLG’s Michael Edwards, writing in the Camden New Journal in 2007:

While Edwards was entirely correct in advocating that councillors clearly need sufficient time and knowledge to be able to consider a complex application,6 he was apparently unaware that the chair of the subcommittee had refused any briefing. Interestingly, Argent’s Robert Evans also argues strongly that committee members must be involved earlier and more systematically if they are to reach informed decisions. Argent has even commissioned research in support of this idea.7 If community involvement is ‘front-loaded’, then it is only logical that the decision-makers must be involved early as well, if they are to avoid being put at a disadvantage. This view was supported by the 2006 Barker Review of Planning.8

The accepted practice in major planning applications is that policy direction is given by the leadership, and within this context, the subcommittee is briefed at regular intervals. Standards of conduct in public life were examined by the Nolan Report9 and informed provisions in the White Paper Modern Local Government in Touch with Local People,10 which in turn informed the Local Government Act of 2000. The Nolan Report accepted that the planning process put elected councillors into the position of taking decisions within a legal framework. However, it rejected the idea that councillors have to behave under the same quasi-judicial constraints as judges or planning inspectors. The Barker Review also accepted the potential benefits of early member briefing:

Following a series of judicial review cases, guidance was issued in 2007 that supports the proposition that councillors should be kept well informed of emerging proposals and should meet applicants for briefing to establish the facts behind a scheme.11 This extends from the pre-application to the post-application period. The proviso is that councillor involvement should operate in a fair and transparent way.12

The problem with the subcommittee was well-known to the leadership, but was never

aired within the Labour group.13 Councillor Woodrow was well entrenched in the party, and was respected by many on the council.14 No other councillor had expressed a desire to chair the subcommittee, and there were fears that any attempt to remove him would end in internal conflict and negative publicity in the local paper, the Camden New Journal.15 The leadership saw the subcommittee and its chair as an irritant, but one to be put up with rather than resolved.

Despite representations from their officers, there was no mechanism whereby Camden’s leadership could break the isolation that councillor Woodrow was imposing on his subcommittee.16 This created difficulties in the negotiations. First, the Camden planning team had in effect been negotiating blind for six years and had little idea of the opinions or voting intentions of at least half the committee. This made the final decision something of a lottery. The second problem was that Argent was well aware of this, and it undermined the position of Camden council’s negotiating team. After all, why spend time and resources on negotiation when the Camden team had no brief from, or influence over, their own decision-makers? Why not go straight to appeal?

It is unclear why councillor Woodrow refused to be briefed on King’s Cross, although there is little doubt that he viewed Camden’s planners with a deep mistrust, believing them to be too close to Argent.17 He also believed that the correct vehicle for the planning decision was a public inquiry. In his view, Camden council wished to control the permission for the King’s Cross development because more ‘planning gain’ would be won that way, and he viewed such negotiated benefits with cynicism. He had also expressed concerns over the acceptability of the ‘hybrid’ application. The isolation that he imposed on himself led to a suspicion among officers that he was in fact being briefed independently by opponents to the scheme. The suspicion, based on hearsay, was only circumstantial, but there were similarities between Woodrow’s views and those of some opponents. If these rumours were true, it meant that far from being independent, he was likely to oppose the scheme, and would attempt to have it refused when it eventually came to the subcommittee.

In the absence of any formal briefings, members of the subcommittee were having to rely on information from other sources, including informal conversations with their constituents and community groups supporting or opposing the scheme. In such an environment there was certainly a great deal of misinformation circulating.18 Regardless of Woodrow’s insistence on absolute neutrality, members were forming views. When Sue Vincent, vice chair of the subcommittee since 2002, became a member of the council’s executive board in 2004, she was shocked and angry at the extent of information that she had not been party to. For her, this confirmed that the scheme was a ‘done deal’ and it was the beginning of her concern that due process was not being applied and that the wider community was being excluded.19 This exposed the tensions between the council executive and the subcommittee.

The interview in the Architects’ Journal

Matters came to a head in September 2004 when the Architects’ Journal (AJ) published an interview with Woodrow in which he condemned the scheme:

Figure 8.1:

Hellman cartoon from the Architects’ Journal.

This statement was particularly worrying since Woodrow had refused any briefing on the scheme, and was presumably relying on his own sources of information. This was ironic, given the highly principled but erroneous stance he had taken regarding bias and impartiality. To emphasise the point that Camden council was now opposed to the scheme, the Architects’

Journal published a cartoon in the same edition characterising Camden council as an ancient steam train blocking the path of an express train entering King’s Cross (Figure 8.1).

Meetings took place between the borough solicitor, chief executive, senior planners and leader. The leader viewed the matter as very serious, damaging and posing a reputational risk to the council. The nature of Camden’s internal politics, however, meant that it was virtually impossible at this stage to challenge Woodrow’s chairing of the subcommittee.21 Instead, the leader sought to reduce the potential risk to the council and asked Woodrow to retract his comments. In September 2004, the borough solicitor wrote to Woodrow asking him to publicly ‘correct’ his statements.22 Woodrow responded in a non-conciliatory manner: ‘The view I expressed in the AJ article indicated no predetermined view of the applications […]. I see no reason to withdraw from the determination of the King’s Cross application and I do not intend to do so.’ He went on to suggest that the AJ was not ‘a journal of record and that its reliability, accuracy and credibility must be questioned’.23

It is unclear why Woodrow refused to retract his comments. It is possible that he suspected intervention by officers in the political workings of the council, a state of affairs that he would not accept.24 It is also possible that he believed the Labour group would back him if it came to a showdown with the leader. Given the strong views of both officers and some councillors, the leader took independent legal advice that confirmed Roberts’ concerns about the risks to the council.25 In the face of Woodrow’s refusal to back down, the borough solicitor reported Woodrow to the Standards Board for England, in September 2004, as being in breach of his duties of impartiality as a councillor.26

Councillor Woodrow’s removal from the decision-making process

It is difficult to assess just how damaging Woodrow’s comments were. They certainly undermined Camden’s credibility in the negotiations. There was also a chance that if the subcommittee refused the scheme on Woodrow’s casting vote, the council could be legally liable should Argent decided to take them to court. Although the risk might be low, the damages could be very high.

The matter might have ended there, with the political leadership unwilling to pursue the matter further, but Argent, initially relatively sanguine about the article, did expect Camden council to act on it. When it became clear that this would not happen, Argent wrote to Camden’s chief executive:

Figure 8.2:

CGI of scheme submitted for planning.

Argent’s letter meant that the council had to respond. The matter was brought to a meeting between senior officers and the executive in January 2005, with a recommendation that Woodrow should either step down as chair or absent himself from the subcommittee meeting. It was referred back to officers to resolve; the leader reasoned that it was an issue that should rightly be pursued by the borough solicitor as the monitoring officer.28 The borough solicitor had no alternative but to pursue the matter. An internal inquiry was conducted with external legal advice. This concluded that Woodrow’s comments, and his refusal to withdraw them, were clear indication of bias and that he should take no part in the decision-making process. While the matter was before the National Standards Board, Woodrow was strongly advised not to take further part in the King’s Cross decision-making.29

Several factors contributed to the officers’ decision to pursue the case, although as noted above, the borough solicitor had little choice. Both Argent and Camden council had been meticulous in avoiding any risk of external challenge, and were acutely aware of the risks posed by taking the scheme to an unbriefed and finely balanced subcommittee with a potentially compromised chair. Given the complexity of the issues, an experienced and capable chair such as Woodrow could have drawn out the debate until the subcommittee ran out of time. This would have had knock-on effects since the timing of the subcommittee was critical. With a local election coming up in Camden council in May 2006, the March subcommittee was the last opportunity to decide the scheme under the present council administration. A new council, with new councillors and new political priorities might have unravelled the entire negotiation process. Furthermore, a new council would be unlikely to hear the case before the autumn, adding to Argent’s doubts about whether Camden council would approve the scheme. Such uncertainty might have persuaded Argent to take the scheme to appeal for non-determination. This was not an outcome that Camden wanted.

The Decision

Jane Roberts stepped down as leader in May 2006. At the elections for committee chairs, councillor Heather Johnson, a long-serving Labour member of the development subcommittee, stood against Woodrow and was duly elected to replace him (although he remained on the committee). Recognising the continuing risk of a divided and potentially hostile committee, Roberts also joined the development control subcommittee for 2005/06, the year in which the scheme would come up for decision. This added her influence and her vote, but it was perceived by some as part of a deliberate strategy to ‘pack the committee’.30

Officers now had to consider how to present the scheme (Figure 8.2 shows a CGI). The report amounted to just under 600 pages of text, in 19 chapters, and with 30 recommendations and 68 conditions. Although there had been no formal briefing of the subcommittee beforehand, it is not true to say that all the members were approaching this application without any prior knowledge. The new chair of the subcommittee, Heather Johnson, was briefed extensively on the background to the scheme as the date for the committee approached. Members of the Labour executive who sat on the subcommittee (councillors Thane, Roberts and Blackwell) had been fully involved throughout. Their support was clear.

However, as the date for the subcommittee approached, it was difficult to gauge how other councillors would vote. It would not be a simple matter of voting along party lines, although it was expected that the Conservative members (with local elections just a couple of months away) might oppose it, simply to score political points through embarrassing Labour. The Liberal Democrat position was unclear. It was felt that several longstanding subcommittee members who were close allies of councillor Woodrow would oppose the scheme. Either way, the likely vote two months before the meeting looked to be on a knife edge:

| For | Against | |

| Labour | 6 | 4 |

| Conservative | 0 | 3 |

| Liberal Democrat | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 7 | 9 |

The Camden New Journal was openly campaigning against the scheme. The edition in the week before the subcommittee, stated: ‘We have to stop this vile, vulgar vision of the future’, quoting members of the KXRLG, and claiming that the scheme was widely opposed by local residents.31 The council’s leadership therefore decided that it was too close to leave it to chance. Councillor John Thane (executive member for Environment) and councillor Theo Blackwell (deputy leader and executive member for regeneration), both members of the development control subcommittee, recognised the importance of the King’s Cross scheme and were prepared to champion it. With an election coming up, they were reluctant to hand over the decision to another administration, fearing that the affordable housing element could be watered down. Their reading of the subcommittee was that the Labour councillors were divided between those who viewed almost all large development with suspicion, and those who saw benefits in growth, especially in affordable housing for those in the greatest need.32 Councillor Thane had championed the scheme throughout and had worked to build broad support through the Labour administration. Councillor Blackwell also agreed to speak to some of the wavering members of the subcommittee, under the auspices of his role as cabinet member for regeneration. Between them, the key issues were re-framed in a number of ways, emphasising ‘now is the time’ for both short- and long-term reasons. First, King’s Cross’s notorious drug and vice problems had long blighted the borough and were perceived as fuelling new drug markets to the north in Camden Town. The council was leading in the use of new community safety powers (antisocial behaviour orders – ASBOs) to tackle such problems.33 Physical regeneration had to follow, a message that newer members, for whom crime was the number one priority, readily grasped. Secondly, King’s Cross was no Canary Wharf, then considered a by-word for commercial-only development and displaced communities. The right balance between affordable housing and commercial development would create the right conditions for future growth and would help to cut Camden council’s growing housing waiting lists at a time when the council relied solely on development to do so. The development would ultimately drive up value, potentially enabling regeneration in the longer term of the huge council housing estates surrounding the site on all sides. As the date of the subcommittee approached, the estimated balance of voting began to change:

This would still be very tight, and the entire strategy could be derailed on the night by a particularly impassioned speech or representation. The paperwork presented to the subcommittee was daunting. To address the lack of prior briefing, it was agreed to hold a special meeting of the development control subcommittee spanning two consecutive evenings on 8 and 9 March 2006. The first meeting would hear representations for and against the development and allow councillors to question the various delegations on points of detail. On the second evening, Camden council planners would present the report and councillors would have an opportunity to ask questions before debating the scheme. The committee adjourned at 22.45 on Wednesday and reconvened again at 18.00 on Thursday. On the Thursday morning, the front page of the Camden New Journal condemned the scheme and urged the subcommittee to reject it.35 The decision was always in the balance, and at 22.30 on the second evening, with only 30 minutes to go before the vote, Stephen Ashworth, Camden’s external lawyer, called Peter Bishop out of the committee room. He had calculated that the committee was going to vote against the scheme and urged Bishop to seek an adjournment. Bishop, meanwhile, had calculated that the committee was probably going to pass it by a single vote, and his view was to continue to a decision. The key moment came towards the end of the debate. John Thane, who had remained silent throughout, spoke in favour of the scheme, setting out his previous reservations and explaining why he now whole-heartedly supported the development. At this point the wavering Labour members resolved to follow his lead and spoke in favour of the scheme. The outcome had been uncertain right to the end, but ultimately the King’s Cross scheme was approved by two votes:

The Conservative councillor, Mike Greene, who was not present had given no reason for his absence. Councillor Greene had been a diligent member of the committee and a strong voice on the council. He also respected Brian Woodrow,

whom he described as, ‘a politician wanting to do his best for the borough rather than himself’,36 and Camden council officers had expected him to vote against the scheme. In interview, however, Greene stated that his non-attendance was due to a combination of a personal dilemma and specific circumstances. He personally believed that the regeneration scheme was essentially one that he supported. However, before the subcommittee took place there had in fact been a meeting of the Conservative party political group where King’s Cross had been debated. The Conservative leader gave a strong steer that his members should vote against the scheme. This was not because the Conservatives necessarily opposed the scheme, but with a local election coming up in May, King’s Cross had become a party political issue. It was a simple piece of political opportunism. With his leader asking him to reject an application that he would have wanted to support, and election campaigning meaning he would not have sufficient time to read the papers thoroughly enough to participate fully in the debate, the easiest solution was not to attend at all.37 Had one Conservative councillor not been absent, and had councillor Woodrow still been chair and voted against, the result would have been a tie. In such a tie, the subcommittee chair has a casting vote. One final unexpected event had serious implications for the scheme. At the last minute during the voting, councillor Stewart proposed an unexpected amendment to a standard recommendation that, following approval, council officers would have delegated authority to sign-off the details of the section 106 agreement. No formal approval of the planning application could be issued without this sign-off. The amendment was that the section 106 agreement should come back to the subcommittee for formal approval. This effectively deferred a final decision until after the local election in May 2006. The councillors were probably unaware of the full implications of the amendment, but officers were dismayed. In retrospect though, Heather Johnson, chairing the meeting, was clear that this amendment was possibly necessary to persuade any wavering members to vote for the scheme.38 Such was the confusion in the final minutes of the meeting that even Argent was unsure of the final outcome. When Peter Bishop went to congratulate the Argent team, Roger Madelin swore vividly, before Robert Evans confirmed that they did indeed have a consent. Normally, this amendment would not have caused serious problems. The subcommittee had approved the scheme, and to revoke the decision would have cost considerable sums in compensation. The section 106 agreement could not be used to change this decision, and signing it off should therefore have been routine. However, there would be no opportunity to do this before the local elections in May 2006. What was not foreseen at the time was that Labour would lose the local election, and that the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats (who had largely opposed the development) would take control of the council.39

Pre-application lobbying

For

Against

Abstentions/ Absent

Unable to Vote34

Labour

6

2

1

Conservative

0

3

0

Lib Dem

1

2

Total

7

7

1

1

The subcommittee meeting

For

Against

Abstentions/ Absent

Unable to Vote

Labour

7

2

1

Conservative

0

3

0

Lib Dem

1

2

Total

8

6

1

1

A last minute amendment

Rebuilding Political Support

The whole process of rebuilding alliances to get the scheme through the subcommittee had to start again. Although planning had been granted, approval of the section 106 agreement was still required, before a consent could be issued. Due to the late amendment this now had to go back to the subcommittee, now controlled by the two parties that had in the end opposed the scheme.

The new leadership settled down remarkably quickly. The council deputy leadership passed to Andrew Marshal (Conservative), who also took the regeneration portfolio. Early briefings with him and Mike Greene (Conservative), who took the environment and planning role, established positive working relationships. The briefings emphasised the following points:

- The scheme had approval, and although the section 106 agreement had to return to committee for approval, any attempt to use this to overturn the consent would potentially expose the council to challenge and damages.

- The scheme would bring in high levels of private sector investment that would transform the southern part of the borough. It was all about business and enterprise.

- The political control over implementation of the scheme, and the subsequent development of related projects, would be the legacy of the Conservatives.

In getting the new administration on side, it helped that the project had been seen as officer, rather than member, driven.40 The new leadership met Argent and they were impressed. They reviewed the terms of the section 106 agreement, and were happy to endorse it. The political line was to proceed, and there was no further debate.

Approval of the section 106 agreement

The project still had to be taken back to committee for section 106 agreement to be signed-off. Greene took on the task of reassembling a cross-party coalition on the subcommittee. The working assumption was that the Conservatives would support investment and development, Labour would support projects that had commenced under its administration, and the Liberal Democrats would vote at random. Although a few councillors wanted to use the section 106 issue to reopen the King’s Cross debate, the legal advice was unequivocal. On 25 November 2006 the subcommittee approved the section 106 agreement by a clear margin.

The planning approvals were signed on 23 December 2006, which was, coincidentally Bishop’s last day working for Camden council. Following Camden’s grant of planning permission, the mayor, satisfied that Transport for London’s interests had been accommodated, endorsed Camden’s decision within four days and passed it on to the secretary of state. The secretary of state’s staff at the Government Office for London (GOL) had received letters asking for a call-in for an inquiry. GOL wavered but accepted that with such a thorough planning report, a call-in would have completely invalidated the principles of the plan-led system and the legitimacy of both local decision-making and the office of the mayor.

Normally, the achievement of planning consent would have cleared the way for construction to begin. The London property market was booming and the King’s Cross scheme was ready to start. Throughout the negotiations, however, it was anticipated that KXRLG would seek a judicial review of the planning permission, and the scheme could not start until this had been resolved.

The Judicial Review

As a judicial review had been considered inevitable, Camden council and Argent’s legal teams had laboured hard to ensure that the procedures followed were watertight, and both were confident that the risk of losing was slight. Under regulations then in force, a judicial review had to be made no later than three months after the grounds to make the claim arose.41 Until the threat had passed, it would have been too risky for lenders to make capital available to start the development. This was frustrating as the London property market was booming. As anticipated, a challenge was made close to the deadline, in February 2007, from the King’s Cross Think Again Group (a partnership of several local groups including KXRLG). The court agreed to limit their liability, should they lose, to £10,000.42 The ‘rolled up’ hearing was held in May 2007. The presiding judge had a reputation for understanding technical development issues. Argent’s legal team, aware of the timetable for hearings had timed matters to coincide with his availability.43

Grounds for the judicial review

Judicial Review

Judicial review is used to mount a legal challenge to a planning permission on the grounds that a public body has failed to follow, or has been inconsistent with, its own procedures in reaching its decision. It challenges the way in which a decision has been made, rather than the rights and wrongs of the decision itself. In the absence of third party rights of appeal, it is the activist’s weapon of last resort against a development. Although a court can only direct that a decision is reconsidered, judicial review inevitably causes delay and brings additional uncertainty to what is already a long, expensive and risky process. And behind every challenge lurks the spectre of a new campaign to reverse the decision. The standard practice is for the challenge to be made by a named individual who is eligible for legal aid, which will cover costs. A review is therefore a relatively cost-effective method of community opposition.

The application for judicial review was made on two grounds, both of which were dismissed. The first was whether the newly elected council had been wrongly advised by officers and the council’s legal consultant that they had no legal grounds to reject the scheme when the section 106 agreement came back to subcommittee for consideration. Given the change in political control, it was argued that members should have had ‘full and unfettered discretion to reconsider all or any of the matters of the old committee’.44 The judgement accepted that Camden council’s advice to members was ‘both clear and correct’, and that as a whole it did not fetter their discretion or ‘box them in’.45

The second ground was that the planning permission went against policy regarding affordable housing. It was argued that the decision should have taken into account emerging guidance on affordable housing (PPS3).46 On this, the judgement found that ‘there is, in practical terms, no difference whatsoever between the definition of affordable housing in PPS3 and the definition of affordable housing in the section 106 agreement’.47 The judgement also found that the advice given to the committee on the adequacy of the affordable housing, and whether or not the committee could decide for itself whether the failure to meet the 50 per cent target meant that there was a departure from the development plan, ‘was impeccable’.

Commenting on the experience, KXRLG’s Michael Edwards had no regrets on seeking the judicial review, and expressed a personal view that such challenges are an important check on the ‘autocratic power of the cliques which run “reformed” local government, and on the power of officers, who are far too often in a dangerously cosy “partnership” with developers’.48 Costs were awarded against the King’s Cross Think Again Group. Camden council pursued these but Argent waived them.

Ironically, the relentless opposition by KXRLG may well have saved the King’s Cross scheme. By October 2008 the effects of the credit crunch were affecting the entire banking industry. The six-month delay between the grant of planning permission in December 2006 and the judicial review hearing in May 2007 meant that Argent had delayed and then scaled back its borrowing to finance the development. Had Argent not done so, it could have faced severe financial difficulties. This is picked up in Chapter 9.

Islington’s Decision on the ‘Triangle’ Site

The final element in the planning equation was the application for the ‘Triangle’ site. As this site was partly in Camden and partly in Islington, it had been agreed in early discussions that it would be subject to a separate application. Should Islington council delay or refuse it, this would not affect the main site.

As discussed in Chapter 4, the leadership of Liberal Democrat-controlled Islington supported the development of King’s Cross, and had no political association with the groups that were opposing the scheme. In March 2006, when Camden council resolved to grant consent for its part of the ‘Triangle’, Islington council had raised no objections to this or to the main application. As with Camden, strategic decision-making started with its cabinet, but unlike Camden, development control was devolved to focus neighborhood committees.49 The one that would deal with the ‘Triangle’ site was Labour controlled.50

Against its officers’ advice, Islington council refused permission for the ‘Triangle’ site in July 2007. Phil Allemendinger suggests that this was due to lobbying of councillors by community activists who opposed the scheme.51 The stated reason for refusal was the extent of affordable housing. Across the whole scheme, 44 per cent of housing units would be affordable. Within the Islington site (2.5 acres of the 67 acre total), the proportion would be 34 per cent. Islington’s own policy was for 35 per cent affordable housing. Over previous negotiations, however, Islington had accepted that the site would be treated as a whole and the council’s executive had made no objection to the main planning application, even commending Camden council on the intermediate affordable housing achieved. While its leadership and officers supported the ‘Triangle’ scheme, it was unable to control the area committee that took the decision. This represented an embarrassment for Islington. In considering Argent’s appeal, the planning inspector’s report in May 2008 stated:

The secretary of state upheld Argent’s appeal and granted permission, and since the inspector approved the application as submitted, Islington lost the changes that it had subsequently negotiated. The appeal and the judicial review, however, had delayed the scheme and cost Argent almost £1 million.

Conclusions

Planning is a contested and inherently political process. Successive governments have tried to address the central conundrum of the system, namely, how to make it streamlined and efficient while maintaining meaningful democratic debate. Government guidance has also tried to provide a framework for transparency in local political decision-making, since any lack of transparency, real or perceived, undermines trust in the system. Given the degree of flexibility that exists in the UK system, trust is paramount.

The King’s Cross planning decision was exposed to political forces and personal agendas, some of which went back a long way and had little to do with the scheme itself. This required political management, at which point the roles of paid employees and elected representatives become blurred. The affair concerning councillor Woodrow is detailed here because it illustrates the tensions both within the council’s ruling party and between officers and councillors. The referral to the Standards Board was taken at officer, rather than political, level. This was technically correct, since the monitoring officer has a duty to ensure probity within his or her council. Nevertheless, the problem was essentially one of political

management, and in many councils it would have been resolved within the machinery of the political group. The fact that it was not, exposed senior council officers to considerable personal risk. The process of constructing support within the subcommittee was not unusual. Lobbying and persuasion is the stuff of politics. The officer’s involvement in this was with the express consent of the council’s leadership and was in line with agreed policy.

Much of the difficulty regarding the decision arose from the refusal of certain councillors, against the clear government guidance to entertain any pre-application briefing from their own officers. Circumstances have changed in Camden. Pre-application briefing of development control subcommittee members is now routine, often in open public meetings. It is also quite normal for officers to sound out the chair or cabinet member and receive a political steer on contentious schemes.53

The change of political control in Camden council was unexpected, but in the end was less significant than it might have been. The fact that King’s Cross was not viewed as a political project associated with the outgoing administration meant that the transition was relatively smooth. Under both administrations the presence of politicians who were prepared to champion the scheme personally eased the process considerably.

Political management is a key skill for both the public and private sector. Even then, unexpected events such as a last minute amendment to a recommendation or a local election can still derail a scheme. In a process as fragile as this, would a public inquiry, as favoured by some councillors and community organisations, have been a better, more rational and more open option? The scheme was compliant with local and regional policy and an inquiry would have undermined the notion of a plan-led system. It would have taken the decision out of local democratic control and placed it into the hands of a government inspector. It would have been costly and time-consuming, and although it is highly unlikely that it would have found any new evidence to add to the debate, the outcome would still have been unpredictable and hard-negotiated benefits could have been lost.