6.

The Middle Game

By the beginning of 2003, a policy framework – the basic principles of the scheme and the main elements of the masterplan – were in place, key stakeholders were on board and a firm foundation had been established for the negotiations. However, key details remained to be thrashed out. Getting this detail right occupied the next three years of negotiations.

Due to the complex nature of the discussions, this chapter is structured thematically, rather than chronologically, around these major areas of contention. It examines the differences between the parties and how agreement was brokered. A planning consent is usually granted with conditions. The quantum and type of housing and adoption of public realm would normally be contained within the permission itself or covered by conditions. The detailed arrangements, for example the allocation of the housing, or management arrangements for street and parks’ maintenance, would be included in section 106. In this chapter we have dealt with housing and public space separately as they were substantive items, even though they occupied a significant part of section 106. (For more explanation on this see pp.107–17.)

It was also becoming clear, however, that there were significant differences in the aims and approach of Argent and its housing partner St George, and this was creating tension.

The Break-Up of Argent’s Partnership With St George

St George had brought specialist housing expertise to the partnership, but there were significant differences in the operational culture of the two firms and these were apparent from the start. At an early meeting during a visit to a St George scheme at Vauxhall Cross, a senior member of the St George team took Bob West of Camden council aside and said, ‘[…] if you think you are going to get any planning gain out of King’s Cross, you’ve got to be joking’.1 In St George’s view, planning was adversarial and a lottery. It was more inclined to go to appeal believing that even if a scheme was refused, it would at least know where the battle lines had been drawn.

This difference in approach reflected the parties’ different development models. Argent intended to retain as much of the commercial property as possible and collect an increasing rent over time. The St George model was to develop and move on, meaning that it focused on short-term value at the point of sale. Although both commercial and residential developments are subject to market fluctuations, housing will usually sell at a price. Offices, however, need occupants; discounting rents alone will not result in lettings, especially in an economic downturn. The two partners therefore also had different risk profiles. At the time of Argent’s bid, Berkeley Homes, St George’s parent company, was considering becoming a broad based property company that would have aligned their approach more closely with Argent’s. When Berkeley decided to remain as a volume house builder, the consequences for the partnership were significant.2

St George was pushing to bring negotiations to an early conclusion and to submit a planning application. When it was clear that Argent would

not do this, St George suggested dividing the site and developing housing in the north. Argent resisted, as this would certainly have impacted on the long-term value of the whole estate. Increasingly, St George became less involved in meetings, eventually taking what Roger Madelin describes as a ‘monitoring role’, reporting back progress (or its perceived lack of it) to its board.3 London and Continental Railways and Exel shared Argent’s misgivings about the partnership and in October 2004 a decision was made to end the partnership and for Argent to buy out St George’s interests.

Argent was concerned at the cost of a buyout, and reconsidered its business plan before making an offer to St George. For Argent, the critical question was the amount by which Camden council was likely to try and reduce overall quantum of floor space in the scheme. Madelin sought assurance on this point in a phone call to Peter Bishop. He stated candidly that the maximum floor space that Argent could lose would be 10 per cent; any more and the scheme would be unviable. Bishop’s response was that Camden council did not have a target, and that it was essentially agnostic about the quantum of floor space as long as the affordable housing was delivered and the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), retail and transport assessments all worked. Some members of the Camden council team believed that this response was a tactical mistake and that if a 10 per cent reduction in floor space had been accepted it could then have been ‘traded’ back in negotiations, in return for other benefits.4 This would have been a standard approach under conventional negotiation practice. However, the whole focus of the negotiations was about achieving a good scheme, not about quantum. In Bishop’s view, a blanket 10 per cent reduction in the quantum of floor space would have been meaningless at such an early stage in the scheme’s development. He was also concerned that a reduction in overall floor space would make the negotiations on housing numbers and the percentage of affordable housing more difficult to resolve in Camden’s favour.

In November 2004 Argent bought out St George’s interest and severed the partnership, albeit at a high cost. Argent then restructured and took on expertise in residential development. As the sole developer, Argent could pursue the negotiations more constructively, and with the long-term aim of consensus building.

Housing

The most significant area of contention in the negotiations over the section 106 agreement was in relation to housing – particularly the amount of affordable housing that the scheme would accommodate.

The quantum of housing

Expectations on the amount of housing to be accommodated on the site ranged from a minimum of 1,074 units (in Camden council’s Unitary Development Plan (UDP)), to a minimum of 1,250 units (in the London Plan), and a target of 2,000 units (in Camden’s Housing Strategy). Community consultations indicated a desired target range of 2,000–3,000. Frank Dobson, the local MP, wanted at least 3,000 and some community groups were pressing for 4,000. The question of quantum was not abstract. Bob West had outlined the constraints in a briefing to the leader.5 The government’s Regional Policy Guidance (RPG3) had effectively concluded that 3,000 houses could not be accommodated at King’s Cross without prejudicing commercial floor space around the transport interchange.6 The historic buildings further constrained development on over eight hectares of the site. Camden council would also require community facilities and a school, and accommodating these with family housing would not be easy in a very high density development. The briefing concluded that 1,800 units might be the upper limit.

Argent needed a minimum amount of commercial floor space to make the scheme financially viable, but knew that cramming too much onto the site would ultimately depress values. The quantum of development flowed from the masterplan, and was always secondary to the objective of creating a successful place.7 Both parties were prepared to consider 2,000 as a target, but minor shifts from housing to offices or vice versa would have significant impacts on the overall value of the scheme. The appropriate quantum of housing could not be calculated until a detailed masterplan had been signed off, but as the negotiations progressed and the masterplan was refined, the quantum of housing gradually increased.

Affordable housing

The percentage and type of affordable housing was to prove the most difficult area for agreement. For Argent it represented the greatest drain on the value of the scheme.

A Brief History of Affordable Housing Provision in the UK

The principle of state intervention in the UK to provide decent housing for less wealthy sectors of society was established in the 19th century, and notions of social and moral reform were embedded in the early town planning movement. The establishment of the planning system in the post-war period coincided with the need for reconstruction and slum clearance. The metropolitan councils established large and powerful architecture and housing departments and planning delivered the land and the utopian ideals. Government intervention occurred on a massive scale.

The restructuring of the state under the Conservative government of the 1980s saw council housing programmes curtailed and provision moved to independent housing associations – Registered Social Landlords (RSLs). Initially RSLs were supported through public subsidies, but these were progressively reduced in the 1990s. Instead, the government began to rely increasingly on the planning system to require developers to provide ‘affordable’ housing within new developments through the section 106 agreement (for more on section the 106 agreement see Figure 6.8 on p.126).

For Camden council it was the absolute key to political agreement. Without a level of affordable housing approaching 50 per cent, as sought in Camden council’s policy, the scheme would undoubtedly have been refused.

For councils facing a major housing shortage and with long waiting lists, the provision of any additional accommodation is important. In practice, when viewed against need, the amount provided through the section 106 agreement is relatively small. But this is not the point. Achieving affordable housing is symbolic; it demonstrates a commitment to deal with the problem and tenants’ groups often hold councils to account on this. For planners, a specific affordable housing target also provides a tangible and demonstrable measure of success.

Despite the long association between planning and housing policy, the provision of affordable housing through planning is still contentious. While it is a role of the planning system to identify sufficient land for housing needs, it is questionable whether it is the role of developers to provide social housing in return for planning consents. Arguably, the private sector has no more responsibility to provide social housing than other services such as schooling or healthcare. In effect, this policy is replacing a government programme delivered through direct taxation to one delivered locally through indirect taxation. Although in theory this should be reflected in land values, in practice the provision of affordable housing represents an opportunity cost, and other benefits including design quality are often compromised.

Whatever the arguments concerning affordable housing, planning should have a responsibility to achieve social mix. A mix of house types, values, sizes and tenures is a strong characteristic of London and creates balanced neighbourhoods.8 In many neighbourhoods the wealthy and poor live alongside each other, rather than being segregated into ghettos or gated communities (an unacceptable feature of many new developments). Social mix was viewed as one of the keys to achieving the objective that King’s Cross should be just another piece of London, and it drove Camden council’s negotiating position at least as powerfully as the housing need argument. Camden planners suggested that for a neighbourhood to be socially sustainable, with functional schools, a good range of local shops and community facilities, wealthier or poorer households should not constitute more than 70 per cent of the population. Clearly this was rule of thumb, but the argument was accepted by Argent.

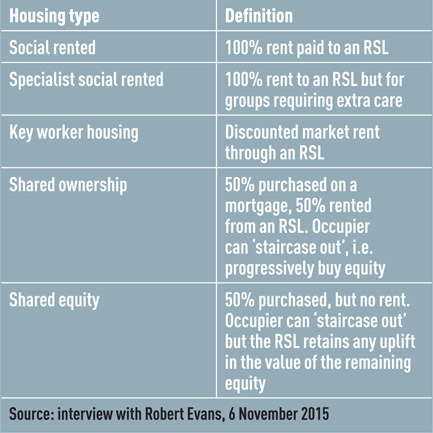

Definitions of affordable housing

There are strict definitions of what constitutes affordable housing under planning policy.9 These rest on a calculation of the percentage of housing costs in relation to household income. This sets affordability thresholds. At the time of the King’s Cross negotiations, the upper limit of affordability was based on an income of just over £50,000 for a couple in a two-bed unit. Within this definition there are different affordable housing options targeted at different income levels. These range from fixed cost rent to forms of shared ownership.10 All affordable housing is usually delivered under an agreement between a developer and an RSL, and the council has the first option to nominate potential tenants from its waiting lists.

Types of affordable housing

There are various types of affordable housing (Table 6.1). In simple terms, social rented housing is aimed at individuals on lower incomes than forms of mid-tenure housing. At the time of the negotiations, grants were available to support affordable housing and Argent was able to sell land to RSLs, albeit below market value. The opportunity cost of each house negotiated from market to affordable amounted to £250,000 off the total value of the scheme.11

Negotiations over affordable housing

The percentage of affordable housing

The Three Dragons Report,12 commissioned by the Greater London Authority (GLA) in 2001, suggested that all housing developments of more than 15 units could provide 50 per cent affordable housing on site. A target that developments should achieve up to 50 per cent affordable housing was then incorporated in the 2004 London Plan.13 Camden council’s revised UDP had already included this target.

Argent had always recognised that it would have to provide some affordable housing but had set 25 per cent as its preferred level. Camden council started negotiations with an expectation of 50 per cent. These positions were aired early in negotiations, during work on the revised Camden UDP (see Chapter 4).14 As the quantum of housing could not be calculated until a detailed masterplan had been signed off, a working compromise was agreed. Of the first 1,000 additional units (over and above the replacement of the 74 units that had existed on the site in Culross Buildings), 50 per cent would be affordable (35 per cent social rent and 15 per cent intermediate), but above this the council would seek 50 per cent with the same social rent/intermediate mix. Argent also guaranteed that affordable housing would be built in each phase of development and that the social and market housing would be integrated, rather than segregated, within the site. The policy was supported by Camden council’s housing needs strategy and by policy in the GLA’s emerging London Plan. The policy was designed to be flexible enough to allow negotiations to continue and to incentivise Argent to increase both the quantum of housing overall and the percentage of affordable housing.

From the outset, both sides agreed that a polarised scheme comprising the very rich and the very poor would not be a satisfactory outcome. It was a private conversation between Madelin and Bishop that opened up the next round of talks. In October 2002 they met by chance at a conference in Birmingham and agreed to review progress on King’s Cross. The issue of affordable housing had to be resolved urgently and Bishop set out an offer. Camden council’s position of at least 2,000 units of housing with 50 per cent affordable was non-negotiable. If Argent could agree this, Camden council could be flexible and would be willing to look at new models of mixed tenure, as long as they fell within the broad planning definitions of affordable housing. If this was agreed, Camden council would use all reasonable efforts to make a scheme work. The offer was accepted.

Although Camden’s policy was to seek 50 per cent affordable above the first 1,000 units, Islington’s policy on the ‘Triangle’ site was 35 per cent. An overall target of 50 per cent affordable housing across the whole site was not therefore supported by policy. To resolve this problem, Camden council indicated a willingness to reduce the social rented housing below 35 per cent and have a higher percentage of mid-tenure housing. Argent in return suggested developing new mid-tenure products. The first was ‘Homebuy’, whereby Argent would subsidise Camden council’s nominees with a 25 per cent interest free loan. The second, ‘Right to Buy – Homebuy’ made the same product available to council tenants who wanted to transfer their right to buy discount (which Argent would cover) to a property in King’s Cross. This had the advantage of freeing up council housing for relet. These products were within the council and the GLA’s strict definitions of affordable housing.

An inherent problem in negotiations on levels of affordable housing is that the amount of government grants or subsidies fluctuates. It was implicit that the Shared Equity, Homebuy and Right to Buy – Homebuy products would be delivered without grant funding. The remaining tenures were, however, expected to require an element of grant funding. Argent argued that in order to be able to agree the baseline affordable housing offer, safeguards would be required should the government significantly reduce the grants. Camden council responded by proposing a cascade mechanism. Under this, Argent would receive a minimum index-linked price for completed units. The price would be based on the cost of delivering these units, excluding land and infrastructure costs. The level of grant needed to achieve this price was benchmarked against levels secured in 2004–06 within the borough. Should the RSLs be unable to pay the agreed price for the unit, the cascade mechanism allowed for adjustments to the affordable housing and eventually for the mix to change. Notwithstanding this, the gap between Argent’s offer and Camden council’s policy still looked intractable. The negotiations were again taken offline and new solutions sought over cups of coffee. Three further areas were explored to provide Argent the reassurance it needed to increase the level of affordable housing: child density, the location of the affordable housing, and Camden council’s nomination policy.

Family units and child density

Camden council wanted to see as high a percentage of larger family units as possible, in order to address the problems of overcrowding in its own stock.15 However, family units were more expensive for Argent to provide and more difficult to fit into a high density mixed-use development. Argent was also concerned that too many large family units would create a disproportionate number of young children on the estate. This would cause management problems. There was little research available to back this view, although Camden’s housing department had experienced problems on new developments in Camden Town. Argent commissioned the Rowntree Foundation to produce an independent research report.16

The report concluded that the maximum child density (the percentage of children aged 5–18) should not exceed 18 per cent.17 This placed Camden planners in a difficult position as they were under pressure to negotiate as much family housing as possible. However, they accepted that a clause in the planning agreement might allow negotiations to be concluded. In return for additional very large family units Camden council agreed to adjust the housing mix and abide by an allocations agreement that limited child density to 23 per cent. In retrospect, it is difficult to assess how serious a point Argent was making here. The issue of child density was a novel concept that Camden had not seen in previous development negotiations. Argent maintains that its primary concern was the welfare and impact of high numbers of children on the management of a large mixed-use estate in Central London.18

Camden council had set out its view early in negotiations that the social and market housing should not be segregated into separate enclaves, but mixed (‘pepper potted’). After several meetings it was agreed that affordable housing should be distributed throughout the scheme and that the buildings should be tenure neutral, that is, indistinguishable from one another (Figure 6.1). In return, Camden council conceded that mixing tenures within blocks would be difficult due to the impact service charges would have on overall affordability. The implication would have been that only tenants on the lowest incomes and receiving housing benefit (which covered service charges), would be able to live in the social housing. This would have polarised the social mix in the scheme and squeezed out key worker housing.

Council nomination rights

The final part of the affordable housing deal concerned council nomination rights of prospective tenants. Allocation is usually on a points system based on individual need. It is a fair system, but it does mean that a developer has no say on the occupants of the social housing in their scheme. Argent wanted a guarantee that

Figure 6.1: Intermediate, affordable and student housing from the park.

Camden council would not ‘dump’ its problem tenants into King’s Cross. This appeared to be a fundamental disagreement and negotiations were again suspended. Camden council considered refusing the scheme and going to appeal. After a period of two weeks in which there had been no contact, an informal meeting took place to explore ways out of the impasse. Argent proposed that it would increase the percentage of affordable housing in return for guarantees by Camden council that it would not use King’s Cross as a ‘sink estate’.

A solution was found by adapting an existing policy. Due to the strong association in the King’s Cross area with crime and drug use, Camden had a policy to not allocate housing to vulnerable tenants or those with a record of anti-social behaviour.19 This was adapted for the King’s Cross development as a ‘sustainable lettings policy’. Under this, prospective tenants had to meet the basic requirements, including no recent record of anti-social behaviour. With this agreement in place, the way was clear for the housing details to be finalised.

Student housing

The final element of the housing negotiations concerned student accommodation. Although not within the planning definitions of affordable housing, it did introduce another diverse element into the community and an increase in the size of the resident population. For Argent this was a good commercial proposition; for Camden council it took pressure off housing stock elsewhere in the borough. Both agreed that student housing would contribute to the creation of a mixed community.

How good was the deal on affordable housing?

In the end, a total of 2,013 houses was agreed, plus 650 units of student housing. Calculating the final quantum was not straightforward due to the many variables. The figures presented to the development control subcommittee for approval were:

| Main site | 1,700 units |

| ‘Triangle’ site | 246 units |

| StPancras Chambers | 67 units |

| Student housing | 650 units |

| Total | 2,663 units |

How good was the deal on affordable housing, and did the parties achieve their negotiating objectives? Camden council achieved its initial target of 2,000 units of housing and Argent had a balanced mixed-use scheme with enough office floor space to make it profitable. There is a question as to how much affordable housing was actually achieved. Under strict planning definitions and using the information presented to councillors in the March 2006 committee report, the figure was 43 per cent on the main site, or 47 per cent when the portion of the site within Islington was included. This excludes the 650 units of student housing. Although there was a need for student housing, it does not come under the definition of affordable housing. If these are added in, however, the percentage of market housing becomes less than 40 per cent of the total.

While negotiations at King’s Cross were proceeding, London and Continental Railways (LCR) was also negotiating planning consents for its site at Stratford, where the percentage of affordable housing was agreed at 35 per cent. In subsequent interviews, Roger Madelin believed that Argent might have conceded a further 3 to 4 per cent in affordable housing, while Robert Evans believed that the deal was right at the limit of what Argent and the land owners could accept.20 King’s Cross is comfortably within Camden’s 70:30 definition of a mixed community (i.e. that no more than 30 per cent of residents should be poor or rich). The opportunity cost of affordable, as opposed to market, housing was approximately £250,000 per unit, or about £210 million. The difference between achieving 47 per cent affordable housing and 35 per cent (the London norm), was around £50 million. Percentages are open to interpretation. What really mattered for politicians on King’s Cross was the political deal. No other major scheme in London was achieving over 40 per cent affordable housing at the time, and the mayor accepted that King’s Cross was in compliance with the London Plan. The total offer constituted a mixed community.

Management of the Public Realm

Figure 6.2:

Study boards on public realm.

Chapter 5 described the physical difficulties of linking the site to its immediate hinterland, and the options for overcoming the psychological barriers that might deter local people from entering and using the site. Central to this was the design and management of the public realm. Since its first document, Principles for a Human City, Argent was committed to high quality, well designed public space (Figure 6.2), and Camden council had similar aspirations. The main area of disagreement was over who should manage the public space. Argent wanted the public realm to be maintained through an effective management regime under its control. Failure to do so, it argued, would impact on rents and land values. Its concern was that in the recent past, Camden council’s maintenance services had been near to collapse and Camden’s ability to maintain the estate to the standards demanded by commercial tenants was questionable. Camden argued that the council was now one of the best in the country, with high standards of cleaning and maintenance. Moreover, if King’s Cross was going to be ‘just another part of London’, its streets must look like London streets, rather than have the sanitised character of a commercial estate.

The issue of public realm management is important. Adopted streets and open spaces are fully accessible to the general public for use within the bounds of the law, and are maintained

and cleaned at the public expense. In recent times many developers have sought to retain the control of public areas, and some cash-strapped local councils see the privatisation of such space positively. But public access to privately managed space can be restricted through a plethora of rules and enforced by private security. Under a heavy-handed regime the young and the poor might be made to feel unwelcome, and effectively excluded.

Two widely publicised incidents helped Camden council’s case. In the first, cleaners who had been laid off by a firm in Canary Wharf had tried to demonstrate against their treatment. Since the streets were not publicly adopted they had been removed by private security guards. Mayor Ken Livingstone had been particularly angered by this case. The right to demonstrate became a test of whether public realm was really public. The second incident concerned two young men who had been removed from the Bluewater shopping complex in Kent purely because they wore the hoods of their jackets over their heads. This led to the ‘hoodie’ test – a breakthrough in resolving the impasse.21

Argent accepted that individuals should have the right to use public space lawfully, regardless of their dress or appearance, but this could not be put into any meaningful planning condition. Should it dispose of the estate in the future, or take another management approach, then the entire character and feel of public spaces could change. It would only take one incident of a parent being told that its children were not allowed to play in the park, for word to spread locally that ‘King’s Cross is not for us’. Although the subtleties of day-to-day estate management practice could not be enshrined in a legal agreement, the adoption of streets could.

The agreement that was reached is still unique to the development. Camden council has the option to adopt the main streets and open spaces, and Argent retains control over the larger formal squares.22 This allows higher quality maintenance and event management in the formal spaces, but Camden council still retains public control over the rest of the site. The feel of the place would clearly be public. Under the agreement, Camden council maintains and cleans to its usual standards, but if Argent requires higher standards, the maintenance specification and budget can be topped up from the service charge.

Environmental Performance

By 2004, environmental performance was featuring on political agendas and it was clear that it would become an increasing concern for future tenants. Addressing it now was good business strategy for Argent. Successive rounds of public consultation had already demonstrated local support for strong environmental performance in new developments. On the political front, the Green Party was challenging John Thane’s seat in Highgate.23 Environmental performance was important, but came below affordable housing and local employment on the council’s priorities. The overriding political concern was not to leave this flank open for attack by the opposition, the mayor or community activists.

Although Argent was committed to providing environmental performance at or above Camden council and the GLA’s policies, the main area of difficulty was in translating such aspirations into practical measures. There was a gap between planning policies and the cost-effectiveness of the environmental technologies available. Emerging technologies were largely untested, policy prescriptions had rarely been thought through and the GLA target of 10 per cent for on-site renewable energy was impracticable. Early calculations24 demonstrated that the developable part of the 27-hectare site could not physically accommodate these requirements and that the costs would have been prohibitive:

- Photovoltaics: 12 hectares of roof space would contribute 1.58 per cent of energy needs at a cost of £78 million.

- Solar water heating: 3.9 hectares would contribute 4.87 per cent of energy needs at a cost of £27.3 million.

- Wind: 525 × 9m diameter or 5 × 70m diameter turbines (as in off shore wind farms) would contribute 4.87 per cent of energy needs at a cost of £27 million and £8 million respectively.

- Ground source heat pumps: a 27.5-hectare footprint would contribute 7.42 per cent of energy needs at a cost of £27 million.

The planning report ‘accepted that full use of these technologies is not compatible with size, townscape and other technical constraints within the site. For example, there is no place on either the main or “Triangle” site that would accommodate or provide sufficient wind speed for even a single 70 metres diameter wind turbine.’25

Argent‘s Andre Gibbs was tasked with resolving the problem.26 Camden council was content that most of the negotiations on energy were conducted between Argent and the GLA in order to comply with London Plan requirements. The London Plan had policies requiring developments to produce energy assessments, but no one was sure what these policies meant in practice. Each policy was tested against practical technologies under the principle of ‘great idea, but what problem are you trying to solve?’. Ultimately the agreed approach was to invest primarily in energy efficient buildings and district heating (Figure 6.3).27 It was reasoned that a district heating plant would pay in the long term and that the necessary pipework could be laid alongside the development’s other infrastructure. The problem was that a district heating system would be required before the first development was completed and therefore required significant upfront investment. Argent solved this by building a temporary boiler (that has now been replaced by the energy centre).

Figure 6.3: Energy centre.

Transport

Transport for London

London’s medieval street patterns and offset grid systems are not able to cope with unrestricted car usage. For many years, therefore, policies have directed commercial development to major transport interchanges and have restricted on- and off-street parking. With the re-establishment of London government and the election of its first mayor in 2000, an integrated strategic transport authority, Transport for London (TfL), had been created. Mayor Livingstone was himself a daily user of the tube and bus systems and a strong advocate of public transport. TfL introduced a congestion charge over central London, and invested in new infrastructure for the underground, buses, walking and cycling.

At the time of the negotiations, TfL was still a young organisation and the task of welding a disparate collection of powerful departments into a coordinated organisation had hardly begun. Each department was focused on maximising its own operational efficiency and there was little internal coordination. A standing joke between Camden council and Argent was that at the beginning of any meeting they had to introduce TfL staff to each other.28

The mayor was clear that if there was substantial opposition to the King’s Cross proposals from TfL, he would oppose the scheme and direct refusal. Had this occurred, it is likely that Camden council and Argent would have joined forces at a public inquiry. It is difficult, even in retrospect, to see what grounds he would have had as Camden council’s transport policies were aligned with the mayor’s. Nevertheless, the threat had to be addressed. TfL was inexperienced, and somewhat naively saw the mayor’s powers as an opportunity to extract significant money from the King’s Cross development.

Transport interchange

The space between King’s Cross and St Pancras stations had to accommodate a new concourse, buses, cars, taxis, cyclists and pedestrians, but the details of this transport interchange still had to be resolved. The Great Northern Hotel formed a pinch point (see Chapter 5) that left only 2 metres of the space to accommodate these requirements beyond the existing carriageway. All the TfL divisions submitted their own plans for separate bus, cycle lanes, taxi ranks and pavements. At the time, TfL had little interest in the public realm and the result was as complex as a motorway junction. It took over a year of negotiation before matters were formally resolved towards the end of 2005. The solution, which involved collonading the Great Northern Hotel (see Chapter 9 for details), did not work when set against the transport models (which predicted gridlock). It was the experience and perseverance of LCR that finally persuaded TfL to accept what it considered to be a less than optimal solution. It now works perfectly well, and justifies the scepticism at the time about the accuracy of transport models.

The Cross River Tram

King’s Cross St Pancras was already the best connected interchange in the UK, handling over 100 million passengers a year (Figure 6.4). There was adequate transport capacity for a major commercial development; it just required minor interchange improvements, sensible traffic restraints, and improvements to local public transport in the form of taxi drop-off points and local bus services.

Figure 6.4:

Walking times from King’s Cross St Pancras.

TfL thought differently. During the late 1990s feasibility work had examined the options for new tram lines in London and one, the Cross River Tram, was planned to be built from Peckham in south-east London to King’s Cross (Figure 6.5). Although Camden council and Argent welcomed this in theory, the problem was its engineering specification. ‘Tram system’ is something of a misnomer. In reality it was a light rail system requiring the extensive rerouting of underground services, wide turning circles and lane priority throughout. A route along Euston Road terminating in front of King’s Cross station seemed the most logical and least disruptive, but was ruled out by TfL on engineering grounds. Instead, it proposed taking the tram through Somers Town and into the site along Goodsway, terminating at the southern end of the Boulevard. This posed two problems. The first was that the stations (with raised platforms, sidings and cross-over lanes) would all but destroy any possibility of the Boulevard becoming a high street and a public space. The second was that the proposed route through Somers Town raised opposition from the local councillor (Labour), Roger Robinson.

Figure 6.5: Route of proposed Cross River Tram.

It might appear that a new tram through Somers Town would bring significant benefits to local people, but Robinson saw the tram as a noisy and intrusive safety hazard and mobilised local opposition against it. The tram threatened to alienate local opinion and there was a danger that this could, by association, feed back as opposition to the King’s Cross scheme. To make things worse, TfL engineers saw a large amount of conveniently empty land at King’s Cross, which could house a tram depot, and believed that Argent, with the mayor’s insistence, would gift them the land. They proposed an open depot of approximately 7.5 hectares or 15 per cent of the land area.

The tram posed a significant threat to King’s Cross. The £300 million project was not funded, the land was not owned by TfL and a depot, sited along York Way, would have completely severed the development from Islington. Nevertheless, TfL saw no need to negotiate or compromise. The mayor saw the tram as critical to improve access to jobs in central London for residents in the deprived areas of south-east London. Camden council and Argent feared that any accommodation for the tram would lead to further demands from TfL for the development to fund the scheme. Camden council’s first response was to suggest alternatives. The first, with Islington council’s agreement, was to extend the tram northwards to Holloway and look for a depot in south-east London. The tram would then only pass through King’s Cross with a simple set of stops rather than a terminus. The second was to suggest a depot on a Camden-owned industrial estate to the north of King’s Cross. In return for the land, Camden council would retain the development rights over the depot. Both options were rejected out of hand. Finally, in exasperation Argent approached the mayor directly. He agreed that the depot would be unworkable and asked TfL to turn its attention to Peckham, where a site was eventually found. This resolved the problem of the depot but not the terminus. Camden council suggested moving the terminus 100 metres into Midland Way between St Pancras Station and the British Library. This was rejected by TFL as it was ‘not at King’s Cross’.

The problem of the tram was really one of politics. The mayor had given a direction that he would not sabotage King’s Cross, but neither would he see his proposals for the tram shelved. He asked David Lunts, the executive director for planning at the GLA to intervene and sort out the problem. Lunts played the critical role of public sector ‘fixer’. In the autumn of 2005, with negotiations completed between Argent and Camden council, he stepped in and brokered a deal between TfL and Argent. Argent agreed to accommodate the tram in King’s Cross as long as TfL reduced the specification of the project. The masterplan was amended and building lines moved back to allow the tram to turn into the Boulevard from Goodsway. Lunts went back to the mayor and described the deal as, ‘as good as you can get’.29 Ironically, the project was never implemented. Boris Johnson, the next mayor, finally scrapped it in 2008, but it had run out of steam long before that. By the time it was abandoned, the Argent scheme had been approved and Argent did not want to re-open negotiations in order to remove the safeguarding lines.

Buses

The quid pro quo of the mayor’s intervention to remove the threat of the tram depot was a request for some help with buses. He accepted Argent’s offer of a temporary bus depot on the site while construction was taking place. This was accepted by TfL and two acres in the centre of the site were leased to them on a temporary basis by the landowners (Exel). Due to poor wording in the agreement, however, TfL returned with a demand that this land should be gifted to it in perpetuity. Once again it claimed the mayor’s support and waved the threat of a ‘call-in’ if its demand was not supported. LCR eventually agreed to relocate the depot to land at the north (and outside the site), in the so-called ‘linear lands’ that were under its control.

Cycling

Both Argent and Camden council were keen to make provision for cycling in the scheme. It came as a shock, however, when in 2004 TfL proposed that Argent should provide the cycle parking required for the two stations. After lengthy negotiations, the scaled-down option of a cycle hub was included in the section 106 agreement (despite the fact that TFL could not come up with an operational model).30 In the end, accommodation was reached with TfL on all these issues, but it took almost 18 months of protracted negotiations. Most of TfL’s demands, well intentioned though they were, fell well outside the demands that a planning authority could legitimately make on a developer. Ultimately, there is only so much public benefit that a development can fund and still remain viable, and Camden council’s priorities were affordable housing, employment and local facilities. While the lack of proper coordination within TfL was a major problem to all parties, it did bring Argent and Camden council together in common cause.

Car parking

In line with policy in the London Plan, the commercial floor space needed very little parking due to the proximity of the transport interchange. Camden council also sought to restrict residential parking and insisted that a proportion of housing should have no parking provision at all. Argent argued that the requirement for 50 per cent affordable housing had already put a severe strain on the scheme, and car-free housing on top of this might depress market values to the point of making the scheme unviable. To resolve the impasse, Argent suggested siting all parking in a multi-decked building on the edge of the site. It argued that the role of the planning system was to regulate the use of private cars rather than ownership. The 10-minute walk to the car park from people’s homes would dissuade the use of cars for short journeys. Camden council accepted the argument.31

Other Planning Benefits

In early 2004, with the main areas of contention – affordable housing and adoption of the public realm – nearing resolution, the negotiations turned to the other planning benefits that would be included in the section 106 agreement. Argent proposed taking the negotiations ‘off site’ to a neutral venue to thrash out the principles. Aware of the sensitivities of using expensive venues, Argent hired a children’s play hut in nearby Coram Fields. The main aspects of the deal were agreed here over two days in March 2004, with minimal heating, sitting on child-size plastic chairs.

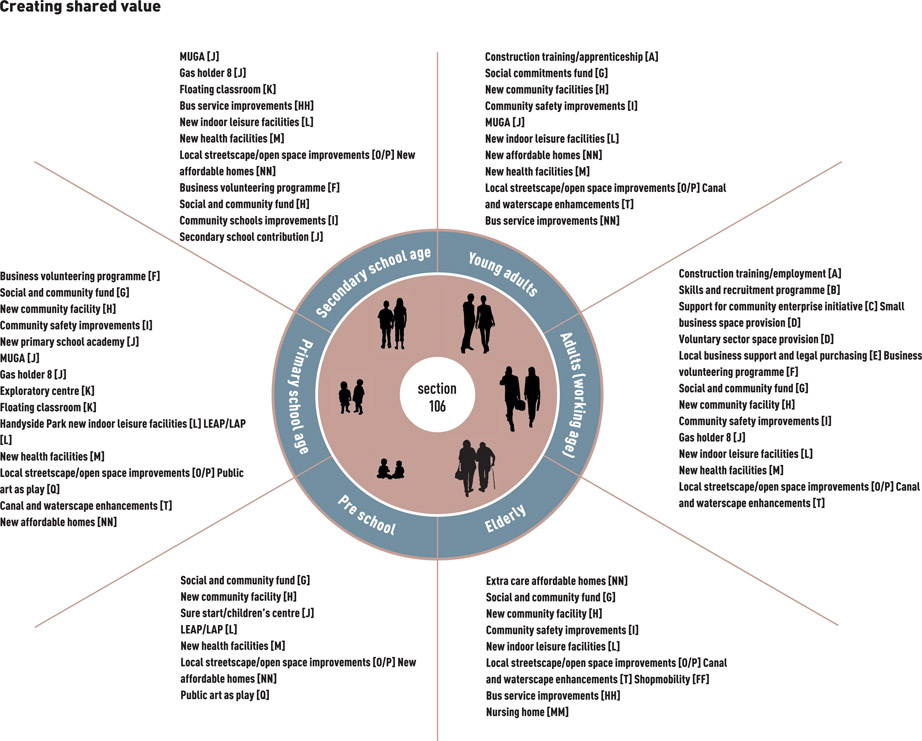

Figure 6.6:

‘The Wheel’.

Camden council and Argent started discussions by focusing on the problem of why local people were not finding work in the vicinity, and Camden council returned to its early proposition: ‘how could King’s Cross make a difference to the lives of local people?’ (see Chapter 4). To answer this ‘The Wheel’ (Figure 6.6) was constructed. The Wheel allowed Camden council and Argent to frame

a benefits package around the life cycle of a local child. Starting with the council’s existing ‘Sure Start’32 programme, it looked at what was missing in terms of local provision throughout the educational life cycle, asked what specific interventions might improve life opportunities, and considered how contributions from Argent might fill the gaps.33 By mapping the first 16 years of a local child’s life, it was possible to assess how Argent’s investment could best be targeted to complement existing programmes.

Primary school and health centre

The initial proposal for a new primary school on the site came from Argent. Camden council checked the demographic projections and for a scheme of 2,000 new homes, somewhere between a one-form and a two-form entry primary school and pre-school facility would be necessary. Both parties accepted that a larger school serving a wider area would help community integration. The same went for the health centre. Since the provision of educational or medical facilities to serve areas outside the development could not be justified under section 106, it was agreed that Argent would provide the shell for both buildings, Camden council would fit-out the school, and the medical practice would fit-out the health centre.

Secondary schools

Negotiations over contributions to secondary education were less conclusive. There was no demographic case for a secondary school on site; indeed, the nearby South Camden Community School had spare capacity. Argent resisted a request for £3 million to improve facilities at the school on the grounds that there was no planning case, which was for the most part true. Underlying this was a concern shared by many developers that monetary payments for facilities outside the site constitute a loss of control, the money simply disappearing into council coffers.34 This was one area of the section 106 agreement that went down to haggling; eventually Argent agreed what was essentially a ‘goodwill’ contribution of £1.5 million towards secondary education in the immediate area.

Leisure centre and library

Public consultation had established an overwhelming demand for a swimming pool and leisure centre. Although under no strict obligation, Argent recognised the importance of responding positively to community demands and was sympathetic to the request. A swimming pool could also be put into a basement and act as a heat sink in the district energy scheme. Initially, Argent opposed Camden council’s desire to run the pool and leisure centre, but after meeting Camden’s leisure managers, conceded that Camden could be trusted to manage the facilities. As Camden would be earning a revenue stream from the new centre, it was agreed that it would make a contribution towards its fit-out.

Local employment opportunities

The provision of tangible local employment opportunities is generally one of the easier issues for a council and developer to agree. It does, after all, resonate with private sector thinking around personal improvement and wealth creation. For Camden council, it was second only to affordable housing on the political agenda. Despite being only a short walk from central London, the most vibrant employment area in Europe, unemployment in the locality remained high. There was no reason to suppose that new jobs at King’s Cross would go to local people unless something positive was done to improve their chances.

Figure 6.7: King’s Cross construction training centre.

Early discussions centred on the provision of low cost (i.e. subsidised) workspace. Argent opposed this on the basis that subsidised rents would just lead to inefficient businesses. Public sector management of business and community space has had a tortured history in London, and the council accepted Argent’s argument. In return, Argent agreed to provide a range of smaller commercial units that might be more suitable for startups. Discussion then switched to the best means to help local people gain employment and entrepreneurial skills.

The 20-year construction programme represented a substantial and sustainable source of new local employment. A standard approach to the provision of local employment is for major schemes to incorporate an element of local training for construction jobs. Most developers are willing to agree to this, but pass the obligation on to their contractors who agree to comply as long as they can choose who they take on as trainees. At best, they reject many local people as unsuitable, at worse they are actively prejudiced against them. However, a package of construction training is a useful entry point to well-paid local jobs if the right vehicle can be found.

Although the Single Regeneration Budget (SRB), LCR and the King’s Cross Partnership (KCP) had already established a training programme, Argent agreed to provide funding to ensure that it continued and a centre was established on land belonging to Argent on York Way (Figure 6.7). To overcome contractors’ reluctance to employ local people, a model was adopted based on the success of the West Paddington Partnership. Here the partnership acted as an intermediary between business and the community, and was trusted because it did not put anyone forward for a job unless it was convinced that they had the skills and the aptitude to do it. Such has been the success of the King’s Cross centre that after the section 106 agreement had been signed, Argent and Camden council agreed to increase its size, sharing the extra costs between them.

Figure 6.8: Development of ‘The Wheel’ as presented in the section 106 agreement (letters refer to sections in the section 106 agreement).

Argent’s direct funding of the training centre was complemented by initiatives to link the local further education college to new jobs at King’s Cross,35 and to encourage future occupants to recruit locally. The result was King’s Cross Recruit; its impact is considered further in Chapter 9. Another part of the package considered how members of the local community might benefit through setting up their own enterprises to exploit new business opportunities in the scheme. Provision was made in the section 106 agreement for training packages, small amounts of venture capital and access to cheap credit for business start ups. This was important since many local residents did not have access to bank accounts and were vulnerable to the usurious levels of interest charged by the unsecured credit sector. The final element was a ‘community chest’ of £1 million for local investment to support a range of different access to employment initiatives.

Development of the Wheel

The first development of the Wheel focused simply on the life cycle from an education and employment perspective, as discussed above. However, it was later developed by Argent into a working programme that covered all aspects of the section 106 agreement (Figure 6.8).

‘The Wheel’ represented a comprehensive and credible package that might begin to break the cycle of deprivation in the surrounding communities. Argent’s board was persuaded that its contributions would complement existing programmes and potentially achieve large benefits.36 It also addressed Camden council’s starting propositions and represented a powerful and persuasive political package that Camden councillors were able to approve.

In summing up the negotiations on the section 106 agreement, Robert Evans of Argent commented, ‘it is what planning is supposed to be about – mitigation and enhancement of impact. The Wheel focused on services rather than contributions. It allowed us to describe what we as a company wanted to achieve. Regeneration is not the same as development; it has a social dimension. In marketing Argent as a company we are proud of this. This for us is our point of difference.’37

Calculating the Value of the Section 106 Agreement

Government guidance on the negotiation of planning benefits is clear; a planning authority can only negotiate benefits that are required to offset the impacts of a development in accordance with its adopted policy. So, the provision of affordable housing and public space are legitimate, as is investment in transport, schools and leisure facilities that cope with increases in demand arising from the development. Provision of benefits also needs to be phased as the scheme is built. Developers will invariably resist up-front payments as, in Roger Madelin’s words, ‘it’s a bit like paying your income tax before you have earned anything’.38 There is a very fine line between legitimate planning benefits and extortion; at best, many developers see planning benefits as a form of tax on their development profits. There may be arguments for tax on developers’ profits, but this is for national, not local government. Successive administrations have been trying to work out an appropriate formula for such a tax for decades,

but so far none has been forthcoming.

Notwithstanding these arguments, a cash-starved public sector will inevitably see section 106 benefits as an opportunity to extract as much money as possible. Inevitably the question will arise at some time in the decision-making process as to whether the council has got enough, or more crudely, have they been taken for a ride by a tougher and more professional developer? To counter this, a planning authority will usually ask for a financial appraisal and Camden commissioned property consultancy DTZ, to do this.39

With so many complex variables in the King’s Cross scheme, this was a difficult and expensive task. Argent was approached to provide financial data, a request that it refused on the grounds that it was not required to provide such commercially sensitive information. After a heated exchange, Roger Madelin elegantly summed up development finance: ‘there are only three scenarios. Number one you lose your shirt, number two you break even and number three you make shed loads of money.’ He hesitated before adding, ‘fortunately I’ve always come somewhere between breaking even and making shed loads of money, which is why I still have a job’.

In the end, DTZ had to use comparative data from other schemes and fill in the detail with educated estimates. The modelling exercise confirmed Madelin’s views. It tested a range of scenarios using different assumptions about content and external market conditions. One result in particular stood out. DTZ had allowed a period of 36 months from the first pile going into the ground to Argent receiving the full rent on an office building (allowing for any discounts and rent free periods). At the height of the commercial office boom in 2004 this was realistic. Extending the construction period to 48 months would effectively wipe £120 million off the value of the scheme.

It is now possible to speculate whether Camden council did get a good deal on the development. Our interviews with Argent confirm that the affordable housing provision at 44–47 per cent was probably as close as the landowners would have accepted, although throughout the negotiations Camden council was at a considerable disadvantage. Despite being well resourced, development finance, price indexing and construction costs were not fields in which Camden council had any significant expertise. Moreover, many of the sums in the section 106 agreement were inevitably based on Argent’s figures. In Robert Evans’s words, ‘planners are not trained to be tax collectors or financial analysts’.40 Camden council also lacked specialist support on housing finance, which Argent admits put it at a significant advantage (although it maintains that it did not exploit this).41

Ultimately, the scale of the possible market fluctuations makes the question of whether Camden got enough, rather pointless.42 The real question is whether the development is, on the whole, a good one and whether it improves the site and wider area. In this respect, planning benefits should rightly be restricted to those needed to make a scheme work and to offset any adverse effects. If at the end of the day a developer makes a high level of profit, this is irrelevant to the planning process. The major items of the section 106 agreement are set out in Appendix 1.

Reflections on the Negotiation Process

While neither the Camden council nor Argent teams had been schooled in negotiation theory, both did contain experienced negotiators. Therefore, it is worth reflecting briefly on the negotiating process and relating this to current theory. This does not seek to be a comprehensive analysis of the theory, but is a simple attempt to compare practice to theory. Negotiation theory is well established, particularly in business deals, wars and labour disputes, although there are fewer references to its use in the public sector, or planning in particular. There are four basic elements of good practice in principled negotiation:43

1 Separate the people from the problem

It is important to maintain credibility and create positive personal relationships through honesty, trust, respect and diplomacy, and to ensure that neither party is forced to lose face. The ability to understand the situation as the other side sees it, is a key skill. The better the relationship, the more cooperation and information sharing there will be. This can involve informal discussions that can help negotiators get to know one another.

Good working relationships had already been established between the council and LCR through the King’s Cross Partnership. This legacy carried through into the development discussions. On King’s Cross, the negotiators established a good working relationship based on trust and honesty. They also recognised that the negotiation process would be lengthy and that positive working relationships had to be maintained. As Argent planned to retain ownership of the estate, it was particularly important for it to maintain a long-term relationship with Camden council.

Both sides also understood and respected the constraints under which the other side was operating. Argent understood the difficult internal politics in Camden council, and Camden recognised Argent’s commercial requirements. Both teams avoided pushing the other into corners by seeking to extract the last drop of blood from the negotiations. There was also an agreement concerning fair conduct and reasonableness; once an element of the negotiation had been agreed it was never revisited.

This principle implies a very different relationship to that commonly observed in planning negotiations where an atmosphere of mutual suspicion and aggressive bargaining often predominates. Both parties did have to tread a delicate line between having an effective working relationship and not compromising (or being seen to compromise) their integrity. It is certainly true that some Camden councillors and some in the opposition groups believed that Camden council’s planning officers had overstepped this line. Informal and off-the-record discussions did take place, but these were instrumental in breaking the deadlock at critical stages.

2 Do not bargain over positions or stated stances

Instead, identify the interests underlying an issue. This allows negotiators to focus on issues of mutual concern with greater creativity, understanding and flexibility.44 Behind apparently opposing positions there may be shared and compatible interests.

Camden council and Argent specifically spelled out their own bottom lines (or positions) on many occasions and there was sufficient trust between the parties for these to be believed. Having done so, the negotiations always looked at the deeper agenda, constantly asking ‘what are we really trying to achieve here?’ (in relation, for example, to the affordable housing targets), or ‘what does this really mean?’ (in relation to public management of public space). As a result, both sides were able to generate creative options to solve problems, rather than operating from entrenched positions. There is no evidence to suggest that either party tried to bluff or horse-trade during the negotiations. If there had been a difference in this respect, it is unlikely that agreement would have been reached.

3 Invent multiple (possible solutions to problems) and look for mutual gains

Identifying options promotes creative thinking, expands problem-solving capabilities and provides a clearer understanding of the interests at stake. There were times when the King’s Cross negotiations were suspended over disagreements, but each side was able to regroup and think creatively about how to break the deadlock, for example by developing new affordable housing models.

4 Insist that the results should be based on some objective criteria

Such criteria might include precedent, scientific judgment, professional standards, efficiency, costs, moral standards, equal treatment, tradition or reciprocity. These provide a basis for logical decision-making, and ensure that parties can look back on the negotiated solution as legitimate. The basic principles for the King’s Cross development were derived from objective research (such as that on child density commissioned from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation) and this common ground formed a firm foundation for negotiations to proceed.

The theory also emphasises the importance of preparation in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of the opponents’ position. In the King’s Cross negotiations each side spent time analysing each other’s bottom lines and strengths and weaknesses (and those of other interest groups). This assessment allowed them to calculate where trade-offs might occur. It also

revealed the relative strengths that each party would have in the event of an appeal and inquiry. Clearly, a negotiated settlement will only endure if all parties are fully empowered to make and honour binding commitments.45 Camden council’s officers spent a great deal of time in preparing the ground internally for negotiations. Some of the most important aspects of this were structural – setting up internal liaison and consultation arrangements; others were conceptual – translating the issues into political statements of priority. Camden council then aligned its own planning policy documents to its negotiating position. Perhaps unusually, Camden’s officers were given a high degree of autonomy by their senior politicians within the parameters set by council policy.

Another principle of negotiation is that all stakeholders should have a place at the table. This is certainly where opposition groups such as the King’s Cross Railway Lands Group (KXRLG) wished to be. Here, practice certainly diverged from the theory, and some of the reasons for this are explored in Chapter 7. Argent and Camden council exercised a high level of control to limit the direct participation of external parties. They adopted a strict definition of stakeholders as those with statutory powers, but agreed to keep them out of direct negotiations. As discussed in Chapter 4, those who could force an inquiry – Islington, GLA, TfL and English Heritage – were consulted, but their place at the negotiating table was restricted. Those writing on the pitfalls of multiparty negotiation do point out that involvement of more than two parties can lead to the formation of coalitions, holdouts, vetoes and betrayals that may reduce the scope for mutual gains.46

Conclusions

This chapter has looked at how a series of technical issues were resolved. Setting the policy frameworks had been relatively easy. Translating them into practice was at times fraught, and on a number of occasions nearly led to a breakdown in negotiations. These issues were resolved largely because the early negotiations had established good working relationships based on objective research, mutual trust and respect. The approach to stakeholder management paid dividends at this stage, and Camden council and Argent were largely able to resolve the key issues between them. It is also important to note that both parties resisted the temptation to haggle, or simply to split the difference where there were disagreements. Instead, arguments were based on well-researched positions and the study of precedents where these existed. Where there were genuine sticking points, the parties resorted to informal meetings to look at different ways to break the deadlock.

In formulating agreements, the importance of the masterplan cannot be underestimated. It provided a framework for testing both the quantum of development and the distribution of land uses across the site. It is unlikely that key issues such as the public realm and the integration of the site with its hinterland could have been resolved in abstract without reference to the plan. There were aspects of the scheme that were truly innovative, such as The Wheel, the public realm management agreement, and some of the intermediate housing options.

Unexpected issues will always emerge during negotiations and the tram was one of them. For a period of time it posed a significant threat, creating uncertainty and potentially pitting the mayor against the scheme. Perhaps more dangerously, it also threatened to turn the local community against the scheme. While the relationship with TfL was the most difficult to control, it did bring together Argent and Camden council.

On the content of the final section 106 agreement it is apparent from interviews that Camden council might have achieved a little more at the margins. Had it adopted a more adversarial approach and employed a degree of brinksmanship, it might have avoided paying the fit-out costs on the school and swimming pool, even though there was no planning basis for this. Eventually, a deal was done, the planners felt they had achieved a good scheme, and the scheme is being built. Whatever financial contributions are agreed, they are relatively small compared to the risks of building in difficult market conditions, as we shall see in Chapter 9.