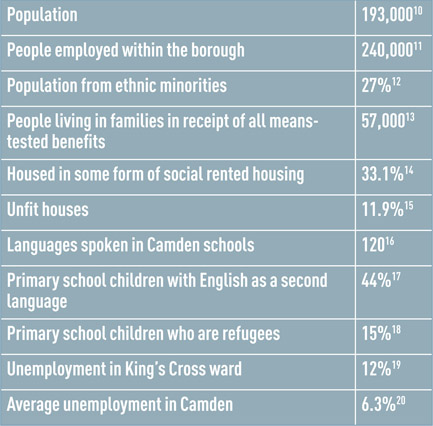

4.

Establishing the Framework for Negotiations

With Argent St George selected as developer for the site, Camden council had to gear up to deal with the development proposals. While the strength of Argent’s bid for the role of London and Continental Railway (LCR)’s development partner was its track record and proposed development process, the absence of any specific proposals meant that there was a long way to go to a development scheme.1 It was anticipated that the negotiation process would take years, not months, and would involve many different parties. Elected councillors needed to provide a clear policy steer for negotiations and to do this, had to be engaged and briefed. Planning officers needed to work out a strategy for the negotiation process, and ensure that an appropriate statutory policy framework was in place, and the Planning Department had to be properly resourced. Other service directorates also had to be prepared for the potential policy, service and financial implications of the development.

This chapter focuses on how these elements were put in place. In order to understand the policy context and organisational culture of Camden at the time, it is important to start with a brief history of the borough and its political power structures.

Camden: The Place and Its Politics

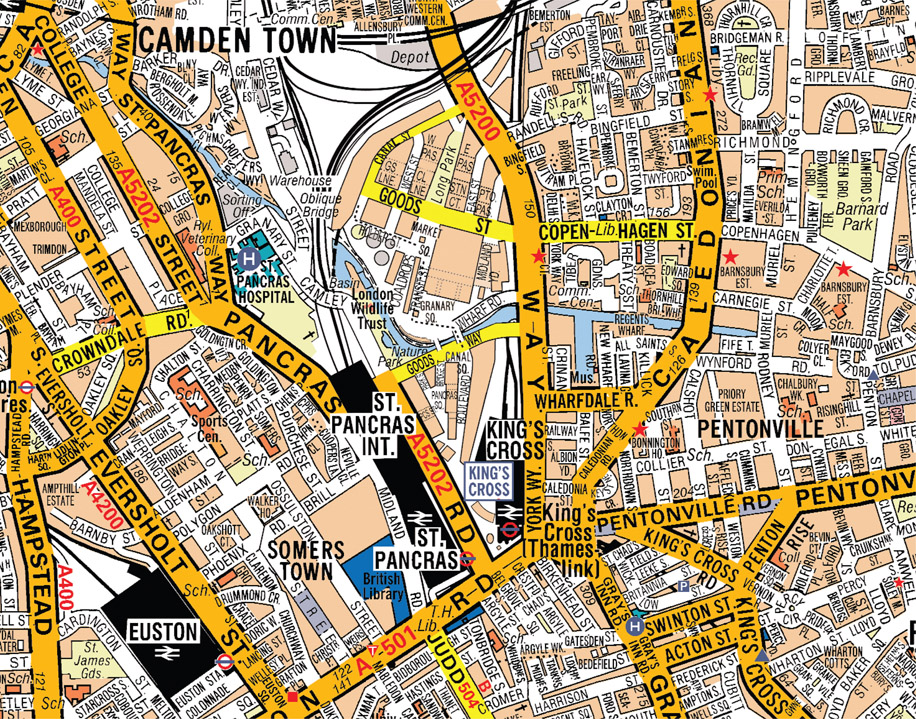

The London Borough of Camden (Figure 4.1) was created in 1965 in a comprehensive reorganisation of London government.2 Camden combined a high business rate base in central London with liberal middle class areas in the north (Hampstead) and traditional working class areas around Euston and Camden Town. The result was one of the wealthiest left wing councils in the country. It was a confident, high tax and high spend borough, committed to high-quality service provision. Very much a Labour flagship, public support was reflected in the results of local elections that saw the Labour Party re-elected term after term.

Figure 4.1:

Map of Camden. Drawn by Allies and Morrison specifically for this book.

Anti-development campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s

Camden politics were marked by a series of landmark campaigns from the 1960s and 1970s, as residents and some of their politicians began first to question and then oppose large-scale redevelopment and the displacement of communities. As the tower blocks rose, so the building conservation movement gathered strength, and a number of epic planning battles took place. Opposition to a proposed urban motorway network saved Camden Lock. St Pancras station itself was saved from demolition by a high profile campaign led by Sir John Betjeman. Covent Garden was saved from comprehensive redevelopment plans in the 1970s, and plans by the British Museum to redevelop the historic area south of Great Russell Street for a new British Library were also thwarted. Other campaigns, such as the ‘battle’ for Tolmers Square,3 were less successful. Due to political continuity in the council, the battle scars from this period were still apparent many years later and a deep suspicion of large scale development remained among some of the councillors.

The social equality agenda

From the 1960s onwards, the ethnicity of the borough diversified, first with large numbers of Irish and Greek immigrants and then in the 1990s with the arrival of Somalis and Bengalis. It also attracted a growing number of younger and wealthier residents, especially in the south. The result was a diverse and pluralistic borough with a deep sense of social justice, which in the words of council leader at the time, Jane Roberts, was ‘edgy and contested’.4

Camden was also (and remains) a place of extreme contrasts. Every part of the borough has areas of affluence alongside areas of poverty. The diversity in the borough encompasses wide inequalities in household income, employment, health, disability, education, housing, crime and other indices of deprivation. These indices are put together to produce an Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD).5 In 2004 the IMD ranked Camden among the 21 most deprived districts in England.6 By taking the difference between the highest and the lowest ward scores on the IMD, Camden was, in 2003, the most polarised borough in London (having a score of 33 compared to the least polarised, Richmond upon Thames at 342). The indices of deprivation also show that the St Pancras and Somers Town wards (immediately west of the King’s Cross site), were in the 10 per cent most deprived areas in England in 2007.7 The effects of this are graphically illustrated by the fact that there was a 15-year difference in male life expectancy between the richest and the poorest neighbourhoods in the borough. In some places this is just a five-minute walk.8 As a result, a key aim for Camden’s Neighbourhood Renewal Strategy (2003) was to ‘reduce the inequalities that exist in the borough, generate social cohesion and create a more inclusive borough’.9 Table 4.1 provides some baseline statistics for the borough around the start of the King’s Cross negotiations.

Many of Camden’s social characteristics were shared with the adjacent borough of Islington. It too combined wealthy and poor areas and had high levels of social housing. Two of its largest council estates, Bemerton and Barnsbury, adjoin King’s Cross, and along with the Caledonian ward sit within the most deprived wards in the country.

The severe budget cuts imposed by the Thatcher governments in the 1980s changed the political environment. Both boroughs went through a brief but disastrous period of opposition to the government, ran up huge debts and suffered near political and managerial breakdown. Decline set in, programmes were abandoned, staff made redundant and frontline services came close to collapse. In Islington, the ruling Labour group failed to take action to respond to the crisis. This led to the rise of a credible opposition and in 2000 the Liberal Democrats took control of the council from Labour.

By 2000, the political environment was very different. In Camden, a new generation of councillors had emerged, led by Jane Roberts, a pragmatic, centre-left politician. Roberts was a modernising leader who, unusually in local government, trusted her professional staff to get on with matters. She set out her priorities as the new leader of the council in a letter to the chief executive in 2000.21 She was concerned over the increasing polarisation and inequality in the borough, and wanted to place social justice and quality of life at the heart of the council’s agenda. She also stressed the importance of effective communication between the council and its residents, and a desire that the council should be ‘thoughtful, imaginative and unafraid to experiment’. Unusually for a council leader, Roberts was also interested in urban planning, and a follow-up letter to the chief executive a few months later provided a clear commitment to the pursuit of good design.22 Roberts was also clear that ‘the authority is in the task. If there is a task to be done, you have to do it, not shirk it.’ As leader of the council she was not under challenge, due partly to her consensual style of leadership, and had the respect of her fellow councillors and officers, but she did not seek to control all areas of council decision-making. Committees such as the development control subcommittee operated with a good deal of independence.

Camden’s decision-making structure

Until 2000, decisions in Camden were made through committees dealing with areas, such as social services finance, planning or housing. These might have a number of subcommittees dealing with specific areas of business such as licensing or planning applications. In an attempt to modernise and streamline decision-making, the Local Government Act 2000, replaced the committee system with the leader and cabinet model. Each cabinet member held a separate portfolio, such as housing, finance, environment or education. This effectively created a two-tier structure, leaving some backbench councillors feeling excluded. Although the subcommittees conducted front line business, they were increasingly detached from policy-making, were no longer under the oversight of a senior committee chair and could operate with a great degree of independence. They came to represent a forum where backbenchers, excluded from influence by the cabinet system, could play a meaningful role in public life. As Chapter 8 demonstrates, this relative autonomy of the development control subcommittee had major implications for the King’s Cross planning application. Council business also became shaped by the personalities and approaches of the individual executive portfolio holders. They developed close working relationships with their departmental chief officers, which in turn gave chief officers a high degree of managerial autonomy. Camden’s particular decision-making structure for the King’s Cross scheme is outlined in the box below.

Engaging Councillors

Decision-Making Structure in Camden Council in Relation to King’s Cross

Full council: comprising all 54 elected councillors. The ultimate decision-making body of the council from which all powers are delegated.

The executive: similar to the central government cabinet and comprising politicians with major portfolios. Chaired by the leader, it met monthly with officers from the senior management team. While it was not a decision-making body, it did set and review council policy and provided an opportunity for informal discussions on strategic issues. It was a useful forum for briefings on aspects of the King’s Cross scheme, and acted as a sounding board during negotiations.

Executive member for environment: responsible for making executive decisions on planning policy, transport and environmental services, including the budget and performance of the environment directorate but with no responsibility for the operation of the development control subcommittee. Until May 2006 the post was held by councillor John Thane (Labour) and from May 2006 councillor Mike Greene (Conservative).

The development control subcommittee: one of the few public committees, and the most important in relation to the King’s Cross development as it would decide the planning application. Over the course of a year, an authority like Camden will receive around 4,000 planning applications, ranging from small-scale domestic extensions to major developments. Roughly three-quarters will be approved, sometimes after negotiated changes. A large percentage of these are minor developments that are delegated to planning officers for decision. Anything of significance though, is decided by the development control subcommittee.

If officers were to have credibility at the negotiating table, they would need to have the long-term support of their local politicians. Local councillors are the democratically elected representatives of local people and their knowledge of, and links to their local area are important. If they were to become alienated by the King’s Cross scheme, the internal politics of Camden would be upset. Senior officers have to be able to manage the political interface, and failure to do this is usually perceived to be a serious and career-threatening weakness.

The King’s Cross development was perceived by many local councillors as being long term, technical and divorced from the imperatives of day-to-day politics. Local politics are largely concerned with the issues affecting people’s everyday lives, such as housing management, school places, street cleaning, refuse collection, crime and parking tickets. Local politicians are very responsive to such issues and a local councillor can often buck national and local voting trends through hard work and popularity. Many political campaigns have been won on a ‘one vote at a time’ basis and this inevitably skews the political agenda towards local, short-term micro-management. For many, King’s Cross was also synonymous with drugs, crime and prostitution. While this state of affairs was not sanctioned, there was a belief among some councillors that at least the problem was containable within a part of the borough that was largely out of sight. Some feared that regeneration would merely result in displacement of the problems to Labour-held wards around Somers Town and Camden Town.

The first issue was how to engage with the planning of King’s Cross without it becoming a party political issue. Since local politics are people-centred, the development had to be framed in terms of its impact on local communities. It was not about planning a distant future but about breaking the cycle of poverty and deprivation in the immediate area. Officers produced four starting propositions, all of which were intended to reframe the development into issues of political concern:

- A child born in adjacent wards in 2001 would be 18 by the time the development was completed. They would have spent their entire childhood living next to a building site. The council therefore had a responsibility to manage the development process efficiently, and to ensure that other agencies did likewise.

- Children entering Camden secondary schools in 2001 would be finishing their education when the first jobs in King’s Cross would be available. King’s Cross was already adjacent to the biggest labour market in Europe, but still had high levels of unemployment. Local residents were competing in a labour catchment area that covered the whole of South East England. What could be done to ensure that a child from Somers Town would have as good a chance of employment in King’s Cross, as someone from Cambridge or Tunbridge Wells?

- Should King’s Cross be like Canary Wharf, Singapore or Manhattan, or should it be a piece of London connected seamlessly with its immediate hinterland?

- How would the relationship with (Liberal Democrat) Islington be managed? How could Islington and its politicians be locked into a shared agenda with Camden? Would Islington demand disproportionate benefits from the scheme?

The aim of these four propositions was to generate interest, promote a strategic debate within the council and start to define political objectives for the development. Once the broad objectives were set by the leadership they could be translated into a policy agenda. It would then be possible to work with external organisations such as Islington and the mayor of London, establish their positions and address differences. A firm political agenda would also make it far more difficult for the process to become sidetracked by alternative proposals that might be developed by opposition groups.

The first proposition was addressed by setting up the King’s Cross Impact Group (KCIG) to oversee the construction process and minimise disruption not only from the King’s Cross development itself, but from the various rail infrastructure projects (see Chapter 3). Work on the underground concourses at King’s Cross St Pancras had already started and brought with it substantial deliveries of materials, temporary construction sites and late night working. Euston Road itself was partially closed for several months while underpasses were reconstructed. It was recognised that if these works generated complaints from the public, and if these were not dealt with effectively, they could undermine the standing of the council with local people and raise opposition that might later transfer to the development.

Sir Bob Reid (ex-chairman of British Rail and chair of the King’s Cross Partnership) was asked to chair the KCIG. Key stakeholders included Camden and Islington councils, LCR, Argent St George, the Regional Health Authority, the Metropolitan Police and London Underground. The group met fortnightly to review complaints and there was an agreement that those present would personally ensure that any problems arising from within their organisation would be dealt with by the next meeting. Over time the complaints dwindled and KCIG was able to meet less frequently. Camden officers were able to demonstrate to their councillors that they had anticipated potential disruptions, understood the political risks, and had managed these. KCIG also provided an extremely useful mechanism for informal liaison and for building effective working relationships and trust between the key organisations.

The other propositions around the provision of local opportunities in education and employment, the quality and nature of the place, became key policy aims for the council negotiations and are picked up in Chapter 6.

One more initiative helped to cement effective officer/councillor working relationships. In the autumn of 2003, a group of planning officers visited Berlin with councillors John Thane and Theo Blackwell (deputy leader and holder of the social inclusion and regeneration portfolios respectively) and Sue Vincent, who was the deputy chair of the development control subcommittee. Over three days the group visited Potsdammer Platz and the newly regenerated areas of East Berlin, met counterparts in the city government and engaged in long debates about architecture, planning and design. As councillor Blackwell said, ‘suddenly development and regeneration got sexy’.23 He had experienced some frustration on the development control subcommittee, seeing good schemes turned down on the opinions of a small group of local activists and conservationists. The visit brought councillor Blackwell into the frame as a key champion of the development, and Berlin provided a useful reference point for the debate about King’s Cross.

Preparing for the Negotiations

The potential scale and content of the development – around 2,000 new homes, a new school and sizeable population increase – would affect every council directorate, and the potential gains and risks made it a key concern for the finance directorate. At the start of negotiations, the implications of the project were debated by the council’s management team. The potential gains, especially in new affordable housing,24 were recognised, as was the risk of reputational damage should the council fail to deliver a scheme with real local benefits. Every directorate committed to engage with the development and to allocate staff time to support the negotiating team within planning. This support continued throughout the process.

Camden’s chief executive provided an initial fighting fund of £500,000 (to be increased as negotiations proceeded), which was placed entirely at the discretion of the planning team. This helped to address the serious imbalance in resources between Camden and Argent St George. A project as large and complex as King’s Cross presented an immense task for Camden’s planning department. A policy framework had to be produced and signed off, a masterplan had to be considered, the quantum and distribution of land uses and traffic generation needed to be calculated and agreed, the impact on conservation areas and listed buildings needed to be assessed, as did the type and the design of housing, the quantity and quality of public spaces, the impact on school places and health provision, job creation, building heights, daylight and sunlight, overlooking and environmental impact. It is usual for a developer to assemble a large team, many of whom are working full time on the project, with the prospect of large performance bonuses. Argent St George would also be able to employ top architectural, planning and legal consultants. Against these forces councils might typically pit a single, middle-ranking planning officer juggling this against 50 other cases and a stream of public correspondence. This is not a fair or winnable contest. The fighting fund enabled Camden to establish an in-house team and to employ top planning and legal consultants. This placed the negotiations on a more equal footing. In subsequent interviews, Argent maintain that far from being concerned by this fighting fund, it welcomed having a well resourced planning team with which to negotiate.

The Negotiating Teams

The negotiating teams are set out in Table 4.2, and these remained in place for the entire period. Both teams were empowered by their respective cabinet/board to negotiate, and either reach agreement or end up at appeal. Both teams had a clear brief and could sign off key agreements as they emerged. In Camden, the leader Jane Roberts and executive member John Thane provided a sounding board and, when difficulties arose, were prepared to back their officers. They also dealt effectively with the internal politics of the council.

The negotiating teams were both led by individuals with a strategic view on the desired outcomes. Roger Madelin’s approach was to ‘never delegate the critical thinking’.25 They were supported by colleagues with deep technical knowledge and experience. This balance of strategic and tactical views helped each team to explore and test strategic options, before testing detailed proposals. The operational members of the teams were able to challenge or veto any strategic option that would have been either unworkable or would have significantly compromised their respective bottom lines. The negotiations were layered with much of the critical detail resolved between individuals outside formal meetings. As the starting point was so open, the negotiations could focus on objectives rather than haggling over detail. Consequently, when proposals emerged, they were usually well understood and even when contentious, each party could at least understand why the other had put them forward. All specific proposals could then be tested against the previously agreed objectives.

The importance of effective partnership working based on trust comes up frequently in this book. Partnership with the private sector was a relatively new approach for local government that had emerged from the regeneration programmes of the early 1990s. Traditionally, very strict rules of engagement had been enforced and any informal or oneto-one meetings outside a strictly controlled office environment were likely to arouse deep suspicion. Social relationships between the public and private sector remain carefully regulated to safeguard the integrity of the development process, but partnership working is based on joint problem-solving and this requires a different set of relationships from the traditional adversarial culture of mutual mistrust between the planner and developer.

In any negotiation there are moments of deadlock when discussions have to move into exploring alternative possibilities that might be controversial or damaging if taken literally (or made public). There were potential risks in using off-the-record discussions to break the impasse, in particular the perception from outside parties that council officers and Argent St George were getting too close to one another. While the council leadership accepted that less formal working relationships between their planners and Argent St George were necessary (and never expressed any concerns on this), some more conservative councillors viewed it with mounting suspicion (see Chapter 8).

The Negotiating Process

While Argent St George had no masterplan, it had worked out a process for developing the scheme and was prepared to involve other parties from the beginning. This process worked on the basis of ‘convergence’. It started with defining, discussing and agreeing the basic questions around the sort of place that might be created. The aim was to consult widely and move progressively through each element of the development, finishing with the finer details. The rules in the process of building consensus were simple: discuss, propose, consult, evaluate, agree, abide by agreements and move on. The last step was crucial. There was an implicit agreement that once a point was agreed there would be no renegotiation. To have done so might have unravelled the entire process.

For a developer to work in this manner might seem logical, but is far from the norm. The standard approach of most developers is to assemble their professional team and produce an initial design, with plans, models and illustrative drawings, often without any prior discussion. The more cynical developers will add more floor space than they really believe the site will take, to allow horse-trading (or to generate

Figure 4.2: Brindleyplace, Birmingham – Argent’s first major development.

excess profits). The scheme is then ‘sold’ to the planners and marketed to local communities. It is little surprise then, that planning is often seen as an adversarial process of damage limitation.

Although there was initial agreement between Camden council and Argent St George on the process, trust and effective working arrangements had to be established. And of course the negotiations had to be tied into the volatile world of council politics. Fortunately, LCR had already done a lot of the groundwork, and Camden council had already articulated its main objectives for housing, employment and wider area integration.

Establishing a vision

The first stage was to establish an agreed vision for the King’s Cross development, describing the kind of place that Argent St George and Camden council wanted to achieve through the development. At their first meeting in May 2001, Roger Madelin invited Camden council’s newly appointed director of environment, Peter Bishop, to visit Argent’s development at Brindleyplace in Birmingham to gain an insight into its development approach. The invitation was accepted and a day was spent looking around the scheme. On the train back to London, Bishop remarked that he thought that Brindleyplace was, ‘good for Birmingham in the 1990s, but would not be good enough for King’s Cross in the 2000s’. The lively debate that ensued went on to cover affordable housing, social integration and the importance of streets as public spaces, a point that made an impression on Madelin.26 There is no doubt that Brindleyplace was impressive (see Figure 4.2). It served as Argent’s ‘calling card’ and confirmed that it cared passionately about what it built. The masterplan was well thought out, Argent had commissioned good architects to design the major buildings, the public realm was of a high, if manicured, standard and the range of independent shops, bars and restaurants was impressive. What was lacking, certainly in 2001, was a sense that Brindleyplace integrated as well with its surroundings, particularly the deprived neighbourhood of Ladywood, as it did with the commercial centre of Birmingham. Brindleyplace felt too corporate. The ‘hard edge’ to the development and the relatively low level of affordable housing that it provided set clear markers for the forthcoming negotiations.

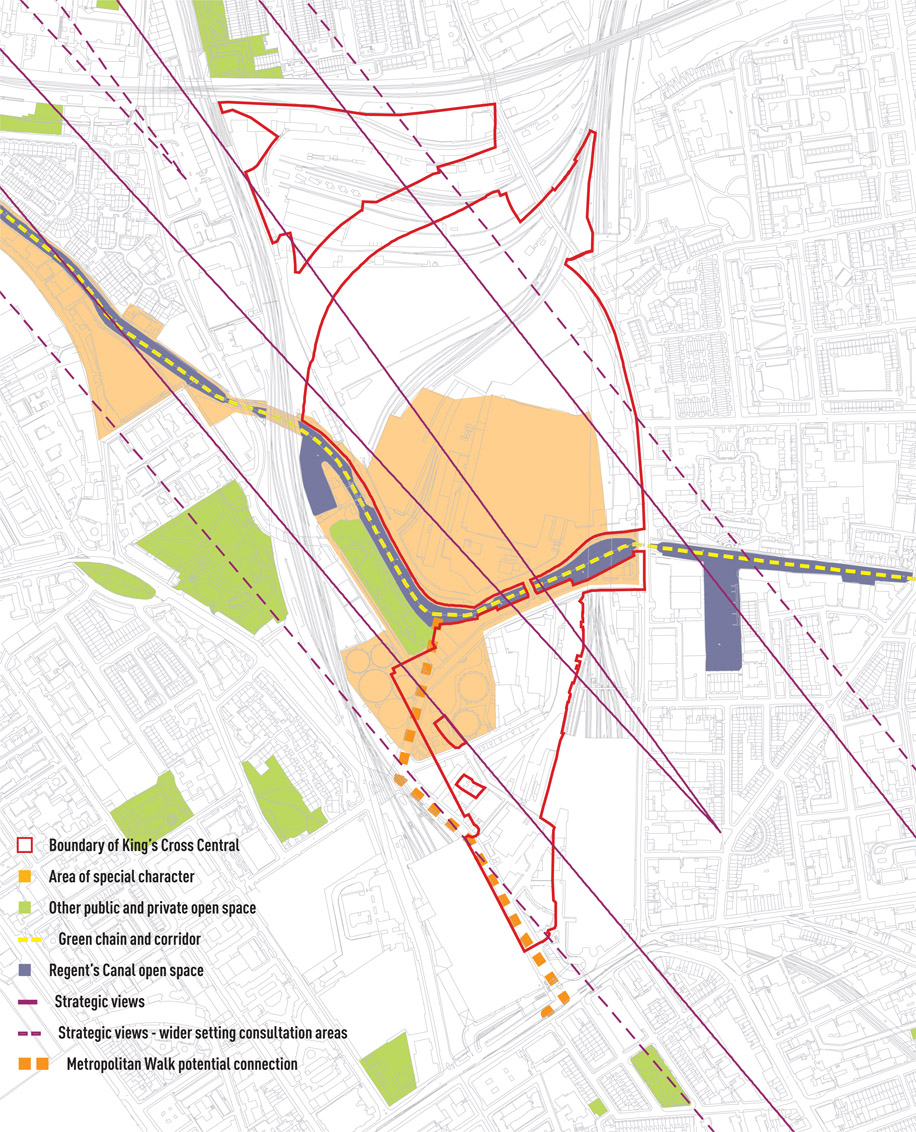

Camden’s politicians feared that King’s Cross would be like Canary Wharf (an isolated and elite office precinct cut off from its hinterland), or that it would be a futuristic place resembling Singapore or Hong Kong. The planning officers’ response was that King’s Cross would be ‘another piece of London’. In practice, this meant that the development should be based on public streets, have squares and parks, a mix of uses and a human scale. There were precedents throughout central London. One of the first drawings produced by the masterplanners Allies and Morrison was a projection of King’s Cross in a future A–Z map directory of London (Figure 4.3). Using familiar and recognisable graphics, this image aimed to illustrate these basic principles, in particular that the development would link into the surrounding neighbourhoods.

Building on early discussions, Argent St George produced a set of guiding principles for the development. These were published in its first consultation document, Principles for a Human City, in July 2001:27

- a robust urban framework

- a lasting new place

- promote accessibility

- a vibrant mix of uses

- harness the value of heritage

- work for King’s Cross, work for London

- commit to long-term success

- engage and inspire

- secure delivery

- communicate clearly and openly.

Jane Roberts wrote a foreword to the document, stressing the importance of the scheme and outlining Camden’s own regeneration objectives. Principles for a Human City reflected Argent’s particular approach to development. Commercially, it recognised that by creating the conditions to improve and enhance the quality of urban life it would also create long-term

Figure 4.3:

Another piece of London – early representation of the King’s Cross scheme superimposed on an A–Z of London.

value. It was as simple as that. The document recognised that King’s Cross would have an important role to play in the London economy, but it also presented an opportunity to benefit the community. The document’s aim was to build a consensus about the fundamentals of the development before embarking on detailed proposals. Argent St George consulted widely on the document (detailed in Chapter 7).

In response to the document, Camden published its own initial objectives for the site – Towards an Integrated City, October 2001.28 The objective was to create firm physical, economic and social links between the development and the local area so that it would be a well integrated part of London. The document set out the positive qualities that the council wished King’s Cross to have. It should:

- contribute to London as a world city, while also relating well to surrounding areas. It should make strong connections with local residential and business communities

- have a mixed character with housing, retail, culture, leisure, offices and open space

- incorporate a rich mix of architectural styles that combine high quality design with lively, safe and attractive streets and public open spaces

- address community safety problems

- respect the Victorian heritage and understand the area’s essential character. Distinctive structures to be incorporated into an outstanding contemporary development

- have high environmental and amenity value, especially round the Regent’s Canal

- have easy and safe routes, with reduced traffic

- embrace sustainable development principles.

These objectives were summarised in King’s Cross – Camden’s Vision, 2002, signed by both Jane Roberts and Steve Hitchins, the leader of Islington council.29 In these two documents, Camden council set out its aims as a basis for consensus-building with Islington and the mayor.

Negotiating Tactics

Avoiding a public inquiry

Underlying the negotiation strategy was a shared desire by Camden council and Argent to avoid a public inquiry (see textbox on p.57).

Although impartial and rigorous, an enquiry would have taken the final decision away from Camden council and present a risk with an uncertain outcome. Since the negotiations aimed to manage risk, the lottery of an inquiry suited neither party. Both Argent and Camden council also viewed a public inquiry as a sign of failure. Given the complex issues and the number of interest groups involved, an inquiry would inevitably have been long and might have put at least a two-year delay on the project. To compound this, there was at the time a 15-month backlog of appeals awaiting a hearing at the Planning Inspectorate. The costs to both parties would have run to many millions of pounds. Both sides saw this as the nuclear option: it was there if needed, but would benefit neither side (see Chapter 8 for further analysis). At the most difficult and acrimonious stages in negotiations the prospect of a public inquiry acted as a major incentive to problem-solving. That said, Camden council had the resources to fight an appeal and

Public Inquiries

A public inquiry is held by the Planning Inspectorate, an independent agency of the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), to consider planning consent refusal appeals. An inquiry is not a law-court, but proceedings are similar, with representation by advocates, expert evidence and witness cross examination. Lasting days, weeks, or – in the case of major infrastructure schemes – years, they might be triggered if:

- the application was not decided in time (16 weeks) and the developer did not agree an extension

- the neighbouring borough (Islington), the Regional Planning Authority (Greater London Authority), the Environment Agency, or English Heritage objected to the scheme

- Camden itself referred the application to the secretary of state (SoS) for a public inquiry.

Advocacy groups and opposition parties may ask for public inquiries but, unlike statutory authorities, have no power to force one. The SoS also has the power to take over planning applications from local authorities, known as ‘call-in’. This is infrequent, usually where development conflicts with national policies, or raises significant architectural issues. A planning inspector is appointed, carries out the inquiry and reports to the SoS who makes a final decision.

Camden’s Success at Planning Appeals

Argent knew that Camden council had substantial funds for an appeal, and as negotiations continued, two successful examples influenced how seriously Argent viewed this. Firstly, Camden council turned down an application from London Underground Limited (LUL) for the redevelopment of Camden Town tube station. Camden council supported this long overdue scheme in principle, due to weekend closures and overcrowding. Yet the proposed design was poor, and LUL refused to engage new architects, not believing that Camden council would refuse on design grounds.30 In December 2003, Camden council did turn it down, fought the appeal, and won.

The second case concerned Union Railways’ application31 for extended working hours for the CTRL into St Pancras construction, due for completion late 2006. Behind schedule, they wanted agreement for 24–7 working hours, for three years.32 The construction area, however, was within 10 metres of Coopers Close housing terrace in Somers Town.

Camden had been inclined to agree on condition that residents would be compensated with weekend respite in local hotels. When Union Railways rejected this, Camden refused the application and the case went to appeal. Camden funded barristers for the local residents, to mount their own challenge under little used powers of ‘general wellbeing’.33 Camden council also managed to get the hearing held in the community hall – the tenants’ home turf. Influenced by the sense of injustice felt by residents, the inspector noted that - since construction had been suspended to allow for disinterment in St Pancras churchyard - ‘the living were probably entitled to the same respect as the dead’.34 The appeal was dismissed, Union Railways was forced to renegotiate, and a suitable compensation package was agreed for locals.

Argent could not be assured of winning. As the textbox on p.57 shows, Camden had proved that it was prepared to refuse applications that it considered unacceptable and had the capability and resources to win appeals.

Some developers, however, see the appeal route as an effective way of threatening planning authorities and short-circuiting the process. Argent was not in this category, but its housing partner St George was and this difference in approach was one of issues that ultimately broke up the partnership. This is covered in more detail in Chapter 6. Paradoxically, some Camden councillors might also have preferred an inquiry. It would have distanced them from the responsibility of decision-making, and would have freed them up to campaign. Should the decision have gone against the council they could blame the inspector, or indeed their own planning staff for failing to put up a sufficiently robust case.

The attraction of raw politics in councils should not be underestimated; councils are at heart political entities. A campaign or public display of resistance can have its advantages and such displays of opposition were familiar territory for some of Camden’s long-serving councillors. At times there was even a suspicion among Camden officers that some councillors relished one last great battle. Winning would not have necessarily been the objective; the struggle alone would have been applauded by some members of the local community and the local press. Councillor Woodrow, the chair of the development control subcommittee, expressed the view on a number of occasions that a public inquiry would be the correct forum for determining the King’s Cross scheme (see Chapter 8).

Camden and Argent St George constructed parallel negotiating tactics. Stakeholders were divided into those who had the ability to force an inquiry and those who did not. In the first group were Islington council, Transport for London (TfL), the mayor, English Heritage and the two local MPs (Chris Smith and Frank Dobson).35 The second group comprised all other interest groups, including local community groups, businesses and individuals. While their views were recognised as important, they did not have the automatic right to trigger a public inquiry. This inevitably put them on a different footing. The public consultation processes for King’s Cross are covered separately in Chapter 7.

Camden council’s tactic was to enter into detailed negotiations with stakeholders who had the ability to force an inquiry, analyse their interests and bottom lines, and provide assurance that Camden would act on their behalf. This effectively denied them a seat at the negotiating table and prevented discussions from becoming unwieldy or over-influenced by a particular party. Negotiations between Camden council and Argent would be difficult enough without other parties being directly involved.

Camden council also wanted to prevent Argent St George from making independent deals with these same stakeholders. As long as they saw Camden representing their interests in the negotiations, they would not be tempted to seek separate agreements with Argent St George. This would have been particularly important in the event of the scheme going to public inquiry. Should this occur, Camden council wanted as many of the key stakeholders on its side as possible in order to present a strong and united case against Argent St George. The upside of this approach was that Camden council took responsibility for building a consensus among public sector stakeholders, thus giving a greater degree of control and certainty to the process. As part of this strategy, Camden council developed specific tactics for Islington, the mayor and English Heritage.

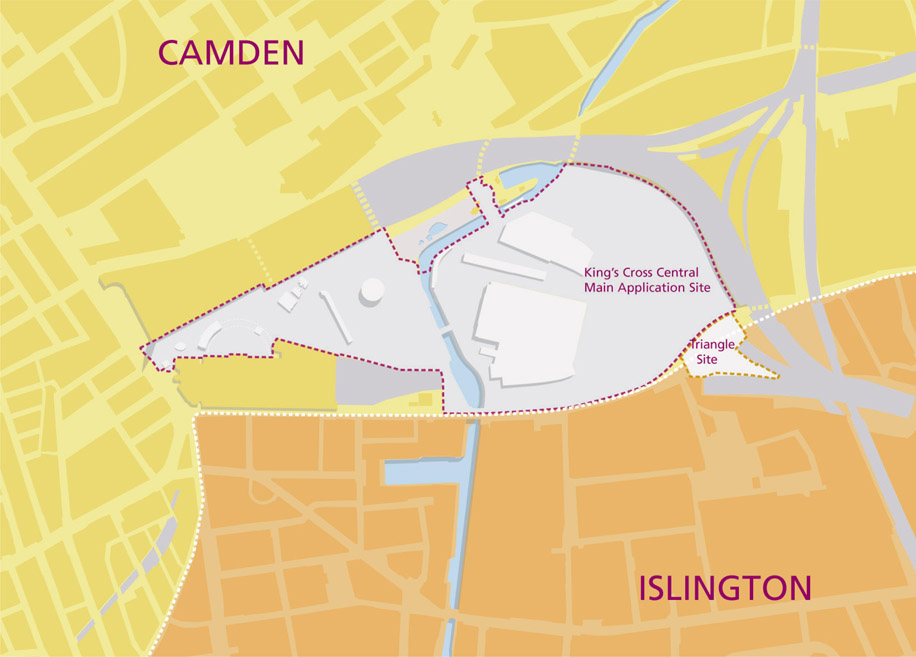

Building a relationship with Islington

As an adjoining borough, Islington council could force a public inquiry if it objected to the development. It was also the planning authority for the ‘Triangle’ – a small part of the King’s Cross site that lay within its borough boundaries (Figure 4.4). Camden officers feared that Islington council could use this position to gain access to the negotiating table and skew benefits (in the form of affordable housing and community facilities) disproportionately away from Camden council. Even if it did not do this, having Islington council as an unknown factor would confuse negotiations and pose significant risks.

Islington council was under a Liberal Democrat administration that was struggling with a severe budgetary crisis and strains on frontline services. There were two possible scenarios: either Islington council would see King’s Cross as a source of cash, or it would be too distracted by its internal problems to get involved. Neither scenario was desirable.

Camden council approached Islington council with an offer to conduct all negotiations on its behalf. This was agreed in principle at a meeting between the councils’ respective directors. The basis of this agreement was that Camden council would have full control over the negotiations, including areas of the scheme within Islington. Camden council would provide office space for Islington planners within its King’s Cross team, and would write Islington council’s planning reports. This would relieve Islington’s hard pressed planners from a considerable burden of work. Islington council would be kept fully informed of the progress of negotiations and its councillors would make the final decision on that part of the development within its borough boundaries. Camden council would also negotiate a fair distribution of benefits between the boroughs, including access for Islington residents to any facilities on the Camden part of the site. This agreement held throughout the negotiations, and Islington council did not object in 2006 to the final application on the main site. It was also agreed that Argent St George would submit a separate application to Islington council for the ‘Triangle’ site. The thinking here was that detaching the application for the ‘Triangle’ from the main site would avoid delays to the main application. Ultimately, Islington council did refuse consent for the ‘Triangle’ site, and the reasons for this are set out in Chapter 8.

London boroughs are fiercely protective of their respective turfs. Although the two councils were under different political administrations, there were regular meetings between the two leaders, who had previously worked together at the Whittington Hospital. The proposal that Camden council would negotiate on Islington council’s behalf was agreed by Steve Hitchins, the leader of Islington council, and he co-signed the foreword to King’s Cross – Camden’s Vision, referred to earlier. This represented a public commitment by both council leaders to the basic principles of the development.

Figure 4.4: Borough boundaries showing main application site and Islington ‘Triangle’ site.

To cede control over a project of this value and importance is almost without precedent but an element of good fortune came into play. First of all, Steve Hitchins was aware of the appalling underlying social deprivation in the area and of the earlier attempts to regenerate King’s Cross. Second, being a newly elected leader with no alliance to the opposition groups who had been active in the area, he was not pulled into opposing the scheme. Third, Islington had the Arsenal football stadium development to deal with and this was occupying a great deal of its energy. In favour of good regeneration schemes, Hitchins trusted Jane Roberts and never considered misusing his position to extract disproportionate benefits from the scheme. Ironically, had Islington remained under Labour control, opposition groups would have wielded greater political influence and it is quite possible that negotiations might have been considerably more difficult.36

Working with English Heritage

The King’s Cross site was dominated by two Grade I-listed stations and contained a number of important 19th-century buildings, as well as a wealth of industrial archaeology. It was largely covered by the King’s Cross conservation area (see Figure 4.5). If English Heritage had opposed the King’s Cross proposals, a public inquiry would have been a certainty. Fortunately, LCR had already established trust and credibility with English Heritage through its proposals to move the triplet gasholders and restore St Pancras station, and Argent St George wished to retain nearly all of the historic fabric on site.

The approach to heritage conservation has a wide range of interpretations. The liberal view is that some change can be accommodated while preserving the essential character of historic buildings (see Figure 5.2); the more pedantic standpoint sees little or no possibility of change regardless of the merits of the case. The interpretations of individual English Heritage officers are often crucial in this respect. Fortunately, the two senior officers, Philip Davis and Paddy Pugh, were pragmatic and positive throughout the negotiations, and working relations were therefore open and candid. English Heritage was given access to the negotiations when appropriate, and its technical expertise proved invaluable. It recognised both the importance of creating a new context for the historic buildings, and that the masterplan had to have a clear and robust logic. Where these were in conflict, detailed options studies were commissioned by Argent St George. Issues concerning key buildings are set out in Chapters 5 and 8.

Working with the mayor and the Greater London Authority

The then mayor, Ken Livingstone, represented the biggest unknown. Livingstone was a left wing (previously Labour) politician who had been a Camden councillor in the 1970s. The office of mayor had been newly established in 2000, and had responsibility for strategic planning under the Greater London Authority (GLA), and for transport under TfL. Livingstone wanted to see London established as a leading city on the world stage and was therefore in favour of commercial development. He should have been an ally to Camden council in the negotiations, but there was a suspicion among Camden’s officers that he might try to interfere unduly in the scheme. This was confirmed in a meeting between Livingstone, Jane Roberts, Camden officers and Argent St George in September 2001. In their recollections of the meeting, Roger Madelin described him as ‘supportive’, while Jane Roberts found him ‘rude and overbearing’.37 During the meeting he offered to ‘sort out’ any problems that Argent might have with Camden

Figure 4.5: King’s Cross conservation areas.

council, and described English Heritage as ‘the Taliban’. He also encouraged Argent to build tall buildings, in contravention of his own London Plan policy on viewing corridors.38

Camden council had not expected to see the mayor align with Argent, and viewed this as a threat to Camden council’s legitimacy in negotiating the scheme.39 The strategy for working with the mayor and the GLA had to be rethought. Camden council’s response was to revise its own planning policy to ensure that it was identical to the emerging new London Plan. It was already revising its policy to increase the requirement for the provision of affordable housing (then at 30 per cent in the existing Unitary Development Plan) to 50 per cent. This would give the GLA no legitimate remit to intervene. It also meant that on issues such as a failure to agree on affordable housing numbers, the GLA would have to support Camden council’s position should there be an appeal. The second aspect of Camden council’s approach was to set up regular liaison meetings with GLA planners to provide updates on progress, while excluding them from direct negotiations. Notwithstanding Livingstone’s support, Argent St George never saw the mayor as a route to gain permission for King’s Cross, and recognised that he might promote his own agenda, particularly around transport. As far as transport issues were concerned, Camden council and Argent St George decided to deal with TfL on an issue by issue basis, on the assumption (which proved to be correct) that they did not have the internal processes in place to coordinate discussions.

In practice, though, the GLA took the view that Camden council was capable of getting on with King’s Cross, understood that its direct involvement was not welcomed, and was content to focus its energies elsewhere. It was briefed by Camden council, and kept the mayor informed. Later in the process it played a role in the background through representing the planning arguments to the mayor in response to TfL’s demands. According to Colin Wilson, now strategic planning manager at the GLA, it is likely that the GLA would have wanted a more central role if the project had taken place at a later date when it was more established.40

Establishing the Policy Framework

In setting local planning policy, councils have to comply with national and regional frameworks. National guidance had already identified King’s Cross as a site where development should support London’s position as a global business and commercial centre.41 When negotiations commenced, Camden council’s policy for the site was covered by Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG) and by Chapter 13 of its Unitary Development Plan (UDP), which had been adopted in March 2000. This had designated the King’s Cross railway lands as an opportunity area, with the potential to create a new quarter for London. The policy aimed to protect features of historic and conservation importance, and encourage the development of office, tourism, leisure, housing and community facilities. Local employment was also high on the council’s priorities for the area. Outside the site, parts of the King’s Cross and Somers Town wards were defined as ‘areas of community regeneration’, reflecting their status as some of the most disadvantaged areas in the UK. Regeneration of these areas was another clear priority.

The UDP did not, however, have an up-to-date policy concerning the provision of affordable housing. Without policy support, Camden council had no basis to achieve its primary political objective of substantial affordable housing on the site. Camden council therefore decided to fast-track a revision to the chapter of the UDP that specifically covered King’s Cross and increase requirements for affordable housing. This process is outlined in Figure 4.6. The reasoning was simple: a new adopted UDP would be subject to extensive formal public consultation, and would carry more statutory weight in negotiations. It would ultimately support Camden council’s decision to approve or refuse the development.

Figure 4.6:

The UDP process.

The decision to review a policy framework in advance of a major development is good practice. However, negotiating this explicitly with the developer concerned is very unusual. In effect, Camden re-wrote the policy to accommodate the first round of negotiations on the scheme. The rationale was that discussing the policy in advance with the developer would simplify the process of getting the plan formally adopted. The more standard approach would have been to have negotiated with Argent after it had

objected to policy proposals and then referred any outstanding issues to a public inquiry. The end results were the same. The revised planning framework cleared some of the major issues, in particular setting out a minimum quantum of housing, and the requirement that 50 per cent of this would be affordable. The key designations of the plan as they affect the King’s Cross site are shown in Figure 4.7.

Eighteen months later, the UDP was approved by the Planning Inspectorate, following an Examination in Public. Three years later, when the planning application was submitted, the council was able to say that the proposed development was fully in compliance with its UDP. By publishing its revised policy in advance of the London Plan being adopted in February 2004, Camden council effectively ensured that the GLA policy was influenced by it and not vice versa.

Deciding the Nature of the Planning Application

An early issue that Camden and Argent St George had to resolve was the nature of the planning application; there were two options – a detailed or an outline application. A detailed application would design every building and public space, while an outline application might be as simple as a statement of the types and quantum of uses, their impact in terms of traffic and job creation, an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and an illustrative masterplan.

This issue was not straightforward. The presence of conservation areas and listed buildings meant there was a legal requirement for a detailed application, since the impact on listed buildings had to be assessed with a high degree of certainty. Argent St George argued that a detailed application would require huge up-front design costs, but the resulting designs would be far too rigid to ever be built over the anticipated long development period. Argent St George would need some flexibility to be able to respond to changes in the market, and it would be costly and cumbersome to have to return to Camden council every time it wanted to change any of the details. Camden council on the other hand could not grant a consent that would be so flexible that it would allow Argent St George (or any subsequently owner) to change the agreement significantly. Both parties agreed that some sort of hybrid application would be required. The problem was that if the scheme departed from the legal requirements this could offer easy grounds for a judicial review (see Chapter 8 pp.165–66). Argent instructed Michael Gallymore of Hogan Lovells and Camden council instructed Stephen Ashworth of Dentons to scrutinise

Figure 4.7: King’s Cross – planning policy designations from Camden UDP.

its work to ensure meticulous procedural compliance. On the critical question of the form of the application, they worked together.

The crux of the problem was that government guidance stated that a planning authority needed to have sufficient information to make a decision. After nine months the legal teams had constructed a new hybrid form of planning application that would comply with planning law. This hybrid application combined the flexibility Argent sought with the level of certainty that Camden council needed. A masterplan would be required to illustrate the form of the development, streets, circulation, specific building plots, building lines and public spaces. A schedule of accommodation was also required, along with the maximum levels for the floor space in each category of use. Argent had the flexibility to draw down the floor space on a series of designated building plots. Each plot had maximum building heights and a minimum environmental specification attached to it. The theory was then tested by the masterplan team. Exhaustive urban design studies considered every combination of height and building use, especially in relation to streets and public spaces.

It was not, however, without its critics. Holgersen and Haarstad42 suggest that the hybrid planning permission further tipped the agenda in favour of the developers, making it one-way and controlled by Argent. The opposition group King’s Cross Railway Lands Group (KXRLG) argued that by allowing a flexible planning permission, Camden council’s planners were effectively abrogating their responsibility to consider later development stages in the light of issues such as the developers’ performance or later changes in government policy.43 These arguments ignore the difficulties of developing a site as complex as King’s Cross over an extended period. There is evidence set out in Chapter 8 that without this form of application, development would not have taken place at King’s Cross. Moreover, the hybrid form of planning application was not challenged, and has since been used in other major developments, most recently at Battersea.

The Bottom Line

Camden’s objectives for King’s Cross had been set in the UDP (first drafted in December 2001). To summarise, there were five ‘bottom lines’. The first was that a balanced, mixed community should be created at King’s Cross. The second was that there should be a significant element of housing, and that 50 per cent of this should be affordable. The minimum quantum of housing, 2,000 units, was specified in the revised UDP, although the maximum was not stated. In the absence of any scientific method of calculation, planning officers thought that 2,000–2,500 units ‘felt’ right. The third was that the development should successfully address the basic regeneration question, namely how it would make a difference to disadvantaged communities in the immediate neighbourhood. The fourth was a requirement that the public realm should remain public in its nature and open to all to enjoy. In particular, the development should include at least two new parks, should be permeable and connect with the surrounding neighbourhoods. The final requirement was that the development should embody exemplary standards of design in its architecture, urban design and landscape and, unless completely impractical, retain and refurbish all of the historic buildings on the site.

Despite having to meet the landowners’ requirements that the long-term value of the site should be maximised, Argent’s bottom lines were more complex. It recognised that an office dominated scheme would be unacceptable to the planners and the community and that a mixed-use development with exceptional public open space would be less risky, more deliverable and in the long term more valuable.

Initial aims were set out in a confidential memorandum from Argent’s non-executive director/founder, Peter Freeman in June 2000.45 The memorandum reflected the need to get St George, LCR and Excel to buy into a planning-led strategy that optimised land values (the principal requirement of the two landowners), while also creating an attractive new quarter of London that would win Camden council approval. In it he stated that:

In relation to Argent’s initial business plan (Table 4.3) the memorandum states:

‘The Parties (Argent, LCR and St George) expect each of the Mainstream Uses to form a significant part of the development. The Parties will seek to minimise the Ancillary Uses unless they can be demonstrated to make a reasonable profit margin on their direct costs and make a contribution of £1m per acre, the Parties will keep the Ancillary Uses to 10% or less of the net developable part of the site, unless those required to build more under Planning Agreements, but will strongly resist those that are excessive.’

The same memorandum set out Argent’s aspirations for 20 per cent of the land take to be high quality public realm. Contrary to the mayor’s desire for tall buildings, Argent favoured offices of eight to 15 storeys with one or two landmark buildings of 20–40 storeys. The objective for residential buildings was six to 10 storeys with one or two possibly going to 15–25 storeys. The rationale for this approach was summed up by Roger Madelin as ‘you build tall buildings – you go bust’.46 (Comparative quantums for the final scheme, heights, land uses and plot ratios are given in Appendix 2).

Another critical observation on the development was made at an early internal meeting in January 2000. It was agreed that while the development should aim to retain the listed buildings on the site, the Culross Buildings would have to be demolished if a central connecting boulevard was to be built. This observation was later subject to extensive analysis by the masterplanning team and English Heritage, but the loss of the Culross Buildings became a ‘cause célèbre’ for objectors (see Chapter 5, pp.89–92).

The objectives of the different parties were not necessarily mutually exclusive. All were in favour of a mixed use development, with a significant quantum of housing, high quality public areas and the retention of the majority of the listed buildings. The fact that the scheme was to be based on public transport was never in contention.

Conclusions

By the end of the first year of negotiations (2001), firm foundations for the development had been put in place. Camden council had a well resourced team, and the council was engaged both politically and managerially. A negotiating agenda had been translated into political priorities and signed off. Camden council had also updated its policy frameworks and had a firm foundation upon which to negotiate. Islington council and English Heritage were largely on board. The stance of the mayor was still a cause of concern and both parties recognised that the GLA and TfL would require careful management. A dialogue had also started with local communities and was revealing key areas of concern and consensus. The main area for debate was clearly going to be over the amount of affordable housing, the management of the public realm and the levels and costs of community benefits. The battle lines were drawn, there was room for manoeuvre, but the parties were still a fair distance apart. Chapter 6 reviews these negotiating positions further.