7

Community Consultation

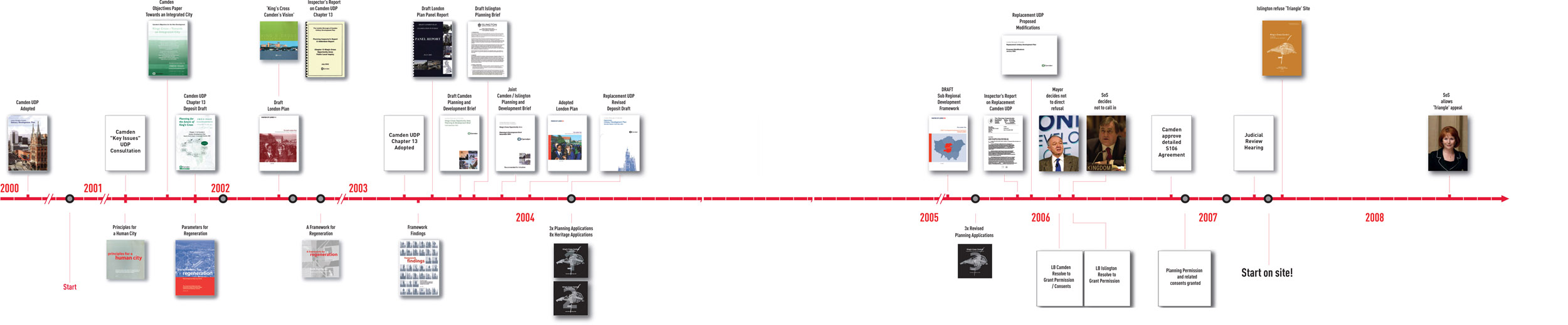

Both Camden council and Argent put considerable resources into consulting very widely with local communities, both at the pre-application stage and on the planning application itself. Community consultations started in July 2001 with the publication of Camden’s Key Issues for UDP: Planning for the Future of King’s Cross and Argent’s Principles for a Human City, and continued throughout the negotiation process (see Figures 7.1 and 7.2). The parties estimate that over 30,000 people were contacted over the course of this work and the processes have won awards for their innovation and thoroughness. Despite this, there remains cynicism among some activists that the development was a foregone conclusion and that the parties were merely paying lip service to any meaningful process of stakeholder engagement.

This chapter presents an account of the consultations that took place, and explores the extent to which these influenced the emerging scheme. It also explores objections to the scheme and to the consultation and decision-making processes, and examines whether a process of ‘consensus-building’ was ever capable of accommodating significantly different views.

Pre-Application Consultations

Figure 7.1:

King’s Cross – the journey to planning permission.

Local authorities are required under planning law to consult widely with stakeholders and local communities on all planning policy documents. National planning guidance also emphasises the need to ‘front load’ consultations, in advance of the submission of planning applications. In order to create binding commitments on consultation, local authorities are required to produce, consult on and publish a Statement of Community Involvement (SCI).1 This is a statutory document that accompanies their local plan (the Local Development Framework). There is no such requirement on developers to consult at the pre-application stage, although government guidance to local planning authorities suggests that their SCI should encourage developers to engage in early consultation on significant applications. The rationale underpinning this guidance is that pre-application discussions could ‘avoid unnecessary objections being made at a later stage’,2 and save time.

At the start of the negotiations, Roger Madelin stated that as chief executive of Argent he ‘would go anywhere, anytime, and speak to anyone about the King’s Cross development’. According to Argent, Madelin alone met with nearly 4,000 people in over 200 meetings in the four years from March 2000.3 Argent’s offer put a human face on the development. Unlike many corporate bodies, here was a person (who often turned up on a bicycle and wearing cycling gear), that one could talk to directly and argue with. If Madelin gave his word, he was personally accountable. This contrasts starkly with the approach of many developers who use PR companies to front up and sell their proposals to a sceptical public.

This offer also meant that Camden council could not possibly be outdone on consultations by the developer. This was not just a matter of local politics and public relations; the council wanted to avoid any possibility that Argent could build alliances with local consultees and capture hearts and minds. Bearing in mind that a working relationship with Argent had not been established at this stage of negotiations, officers feared that a marketing operation from the developer might in effect buy local support and undermine local councillors. In the event of an appeal, Camden council needed the community on its side. Madelin’s statement therefore triggered a dual (and slightly competitive) process of extensive consultation.

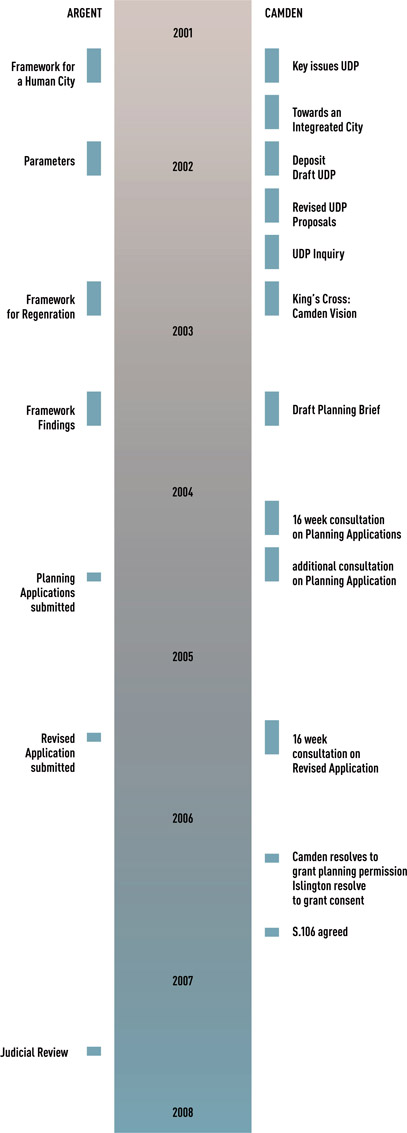

Figure 7.2: Consultation timeline.

Camden council’s consultation strategy

The initial consultation strategy for King’s Cross was based on the following commitments:4

- maintain high quality publicly accessible information

- maintain the King’s Cross development forum in representing local opinions as inclusively as possible over the whole King’s Cross area

- continue consultation with hard to reach groups not wishing to attend the forum, including minority groups

- continue the planning advice and support programme for black and ethnic minorities, and for any others that request it

- continue working in schools, with young people and youth clubs

- continue working with the principal community groups at conventions, events, etc

- set up focus panels or workshops on particular topics, such as accessibility (including disabled people, the elderly and those with young children), safer and better streets, local priorities, etc

- develop ways of bringing local people into design development, such as designs for streets, shopping/leisure/health uses, etc

- develop ways of easier access to decision-making processes

- encourage and support community groups working together on wider regeneration initiatives

- create innovative ways of sustaining long-term and widely representative community involvement.

The consultation processes

As noted in Chapter 4, the negotiation process between Camden and Argent was based on ‘convergence’. This implied working together and moving from the first principles to more detailed proposals. The consultation processes reflected this. Both sides consulted separately on each of the documents that they produced as they jointly refined the scheme from principles to proposals (Figure 7.2). The consultation results were then fed back into the negotiations and were used to challenge or validate proposals as they developed.

Camden’s formal consultations started with the revised chapter on King’s Cross in the Unitary Development Plan (as discussed in Chapter 4). Proposed changes were summarised in a consultation document on Key Issues in July 2001.5 This was published at the same time as Argent’s Principles for a Human City.6 In response to the Principles document, Camden published its own initial objectives for the site in King’s Cross – Towards an Integrated City in October 2001. Argent St George’s next consultation document in December 2001 was Parameters for Regeneration.7 This put all the factual information that Argent had amassed on the site and the surrounding neighbourhoods into the public domain. The thinking here was that if consultation was to have any value then the public had to have access to information on constraints and opportunities. To do otherwise would have resulted in too many ideas and suggestions being dismissed as unfeasible. In June 2002 Camden council then summarised the emerging policies for its draft of the new UDP chapter on King’s Cross in King’s Cross Camden’s Vision.8 All of these documents went out to public consultation. Figure 4.6 summarises all the stages in Camden’s consultation on its new UDP chapter for King’s Cross.

Argent developed its ideas in A Framework for Regeneration,9 which contained tear-out pages for responses and was accompanied by a consultation roadshow in Camden and Islington. It also appointed a specialist consultancy, Fluid, to run consultation events for harder to reach groups, such as youth and women’s groups. The responses were compiled into nine short films on the Argent website. Nearly 200 people attended workshops in December 2002. By mid-March, Argent had received 133 written responses to the framework document, which were summarised in Framework Findings in June 2003.10

Camden council went on to produce and consult on a Draft Planning and Development Brief for the King’s Cross Opportunity Area in September 2003,11 which was itself informed by several workshops with the King’s Cross development forum and other groups.12 In this process the King’s Cross Team contacted over 100 individual community groups to reach as wide an audience as possible, with a specific focus on hard to reach and non-English speaking groups. More widely, officers contacted over 700 groups offering to attend one of their meetings and over 40 sessions were held with local community groups. Over 4,000 people took part in discussions. In addition, there were flyer

drops, workshops and stalls at local festivals. The council supported these meetings with interpreters, translation services and crèche facilities. Findings from consultations were reported back to the leader, senior politicians and to groups themselves, and fed back into the development of the planning brief.13

To support the consultation processes, the council undertook a mapping exercise to identify all local business, amenity and residents’ groups. Argent commissioned a database of all employers within a mile of the King’s Cross site, as a basis for outreach and dialogue. The developer, Camden council and the King’s Cross Partnership also jointly commissioned a study and consultation process with creative industries to identify the scope to develop the sector.14 A growing understanding of the diverse communities in and around King’s Cross, as well as lessons learned from the consultation phases were constantly fed into the negotiations.

The influence of the pre-application consultations

Camden

It is not easy to track issues that were raised in these early consultations or their influence on the shape of the scheme.15 However, both Camden council and Argent are clear, from attending meetings, listening to debates and facilitating workshops, that the emerging King’s Cross scheme was broadly supported by the majority of the surrounding communities. Camden’s officers would have found it difficult to present the scheme to their councillors had there been widespread community opposition.

From Camden council’s point of view, the consultations threw up relatively few surprises. The council’s dialogue with local communities had evolved over a long period of time, even preceding the Argent scheme and Camden council believed it had a good understanding of the prevailing political conditions in the local area and the needs of the community. The need for affordable housing, open space, recreation, jobs and better education were all central to negotiations from the start. The consultations did, however, help to reinforce Camden’s negotiating position, for example by emphasising the degree of support for affordable housing and an accessible public realm. Argent recognised that a broad consensus on certain issues was emerging from the consultations, and that Camden councillors could not ignore the main items. In this respect, the consultation provided an evidence base for the negotiations. Had the scheme ended up at a public inquiry, it is highly likely that this evidence would have formed a significant part of either side’s case. The consultation also allowed Camden council to weight the community demands and refine the section 106 agreement to deliver them. A number of items in the scheme, such as the swimming pool and health centre, would not have been provided without clear community demand.

Argent

Argent suggests that in the most general sense, the knowledge and experience that it gained from consultation significantly improved its understanding of the site and its context, and contributed positively to the evolution of the scheme. According to Argent’s Robert Evans,16 the consultations in 2001–02 that led to the Framework document changed the scheme significantly in relation to:

- the townscape and grain of the development south of the Regent’s Canal and its relationship with retained historic buildings

- the retention and refurbishment of the listed Great Northern Hotel

- the layout and alignment of new buildings north of the canal

- the relationship between the masterplan and the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL) embankment and York Way

- the accommodation of a principal park at the centre of the scheme.

Between the Framework document in September 2002 and the first applications in May 2004, feedback from consultees resulted in further changes, such as: - the decision to commit to a minimum number of residential units

- retention and reuse of the listed gasholders and other the historic buildings north of the Regent’s Canal

- provision of community, health, education, cultural facilities, and sports and leisure uses

- preparation of an implementation strategy to address long-term delivery

- preparation of a public realm strategy to respond to aspirations for highest quality public realm.17

Consultations on the Original Planning Applications

Camden council’s consultation process on the planning applications was reported in detail in the March 2006 Committee report, and is just briefly summarised here.18 Consultation on a first set of planning applications, submitted in May 2004, was conducted over 16 weeks during that summer. Once again it involved a wide range of approaches to consultation, each tailored to suit the relevant target audience, with exhibitions, newsletters, leaflets, web pages, conferences, games with local schools,19 walking tours and workshops.

As well as the statutory consultees,20 the council contacted all property owners and occupiers within a 1 kilometre radius of the site (approximately 30,000 households and businesses in Camden and Islington), and all non-statutory organisations and local groups. Householders received a consultation leaflet with details of the application schedule and all community groups were offered a council presentation. Printed and online information was also used to target users of public transport,

including commuters. Planning Aid for London (PAL)21 was commissioned to facilitate outreach and community engagement work with community and resident groups, and to provide specialist independent planning advice. Meetings with 50 individual community groups took place. PAL also trained over 40 members of the King’s Cross Community Development Trust (KXCDT) to be facilitators, who were then able to undertake consultation in their own communities. Further consultations were also carried out by Islington council’s King’s Cross Team, and Camden Primary Care Trust, which ran a health impact assessment for the whole of the King’s Cross developments. Camden council then consulted on a number of specific issues in October 2004 through workshops facilitated by PAL, with the newly established citizens panel, Camden Talks, and with a focus group for young people.

Influences of consultations on the original planning application

In response to this community feedback, Argent incorporated a number of revisions in its revised planning application in 2005:22

- Changes to landscaping proposals for Station Square and Pancras Square.

- Better pedestrian connectivity between Granary Square and the canal.

- New landscape proposals for Handyside Park, including children’s play areas.

- Changes to Cubitt Park to provide a contiguous green space framed by tree planting. Widening the park at north end, to provide larger and more useable space for informal recreational activities and events.

- Reuse of the gasholder No 8 as a new play facility and public open space.

Consultations on the Revised Planning Applications

A further eight-week round of consultations was undertaken following receipt of revised plans and environmental statement reports from Argent in September 2005. This involved re-consulting all respondents from the first round of consultation, again with the support of independent facilitators from PAL; 27,000 consultation letters were sent out to local residents and businesses in both Camden and Islington. A further 237 consultation letters were sent out to local community groups, and Camden council officers attended local meetings on request.

Consultation responses

At the completion of the formal consultation period, the council had received 267 responses from statutory authorities, public organisations and individuals. All responses were categorised into 29 topic areas and entered into a database. This information was provided to all the councillors in each borough, and to Argent. Camden council’s consultations were also monitored by Camden’s internal consultation board, a corporate group set up to coordinate consultation activity and promote best practice in the borough.

The report to the March 2006 subcommittee contained 102 pages summarising and analysing the consultation responses to the planning applications. These came from 20 statutory authorities, local councillors, the two local MPs, 10 non-statutory authorities and 71 local groups including resident’s groups, faith and cultural groups, conservation bodies, leisure and interest groups, the King’s Cross Development Forum, the King’s Cross Business Forum, KXRLG and Camden Talks, the council’s citizen’s panel. It is impossible to document here every point that emerged from the consultations, and the summary below is inevitably partial.

Critically, none of the primary statutory consultees (who might have triggered a public inquiry), raised significant objections to the scheme. Many other consultation responses supported the scheme. For instance, Camden Friend’s of the Earth encouraged the two councils to vigorously defend their comprehensive brief for the development. Camden Square Tenants and Residents’ Association supported the regeneration plans and the links to surrounding areas. Create King’s Cross was very supportive of the values underpinning the proposals, and the King’s Cross Business Forum welcomed the proposed development, believing it essential to the future well-being of local business and residential communities.

In contrast, a number of objectors such as The Cally Rail Group and KXRLG objected to a perceived lack of clarity, detail or certainty in the hybrid applications. The main areas of concern from local communities in relation to the final planning application are as follows:

Offices

Several consultees (such as The Cally Rail Group, Camden Civic Society, KXRLG, the Chinese Community and Camden Green Party) objected to the overall balance of the development and wanted a reduction in the amount of office floor space, particularly south of the canal.

Housing

Some respondents (such as KXCDT and The Islington Society) favoured more housing, particularly more affordable housing. The Community Housing Association and the Bangladeshi community argued for an increase in large units for families.

Heritage and conservation

The main critic on heritage grounds was the King’s Cross Conservation Area Advisory Committee (KXCAAC). It was concerned that the unique heritage of the site would be severely compromised by the proposals. In particular, it opposed the loss of North Stanley Buildings and the Culross Buildings (see Chapter 5). In relation to other aspects of the historic fabric, it argued that Argent’s proposals showed little appreciation of their historical and archaeological value and treated them as objects of incidental decorative interest.23 KXCAAC argued that the canal and its walls were not part of Argent’s site and felt that the proposal to open up the canal as public space would seriously damage its tranquillity.

Built form

There were concerns (from groups such as Camden Green Party, The Regent’s Network and KXCAAC) that the proposed building heights would have a negative affect on the setting of historic buildings and the canal.

Community facilities

There was strong support for the publicly-run sports centre, swimming pool, health facilities, pre-school facilities and primary school. Other consultees sought a museum, community arts space, community theatre, market, cinema, more play areas for young children, space for the various faith groups, and for community meeting space gifted to local groups. Some respondents (such as the Bangladeshi community and KXCDT) also considered that a secondary school should be provided on the site.

Retail

Consultees supported the provision of new shopping activities, particularly convenience shops catering for local needs.

Transport

Most transport comments related to the development’s potential impact on local roads and public transport networks. Suggestions from the KXCDT, among others, included impro ved access to public transport at the northern part of the site through a new Maiden Lane station on the North London Line (now the Overground) to serve the proposed developments, or re-opening the York Road underground station. There were concerns from some groups (such as Camden Square Conservation Area Advisory Committee) that too many car parking spaces were proposed, particularly in a multi-storey building.

Community safety

Many respondents supported a mix of uses both within buildings and across the site, to create 24-hour natural surveillance.

Open space, recreation and biodiversity

Many consultees (such as KXCAAC, the Somers Town People Forum, and the Iraqi, Sudanese and women’s workshops) felt that the proposals did not include sufficient green or other forms of public space, or that there were too many hard surfaces on the site. There were concerns from many local groups (such as the London Wildlife Trust) regarding the possible impact of a proposed new pedestrian/cycle bridge on Camley Street Natural Park (CSNP), and of the development generally on the biodiversity of the Regent’s Canal.

Environmental sustainability

Camden Friends of the Earth acknowledged that some of its concerns on the environmental standards in the original application had been addressed. Environment groups generally felt that the applicants had not made sufficient firm commitments or firm targets for achieving sustainable development, and did not strive for environmental excellence. There were still demands for Argent to commit to providing 10 per cent of energy needs on site and other measurable initiatives.

The influence of the consultation process on the scheme

In the view of David Partridge, the managing partner of Argent, one of the most important impacts of the consultations was on Argent’s internal values.24 Consultation had allowed Argent to understand not only what people wanted from the scheme, but why they wanted it. Partridge contends that the prolonged relationship with the community impacted directly on Argent’s internal culture. The fact that Argent’s Robert Evans can still recall comments that he heard from individual consultees perhaps underlines the point.25 In the strongly contested areas of negotiations, particularly on the levels of affordable housing, section 106 contributions and the provision of facilities such as the swimming pool, it is probable that the consultations tipped discussions in Camden council’s favour by making Argent more sympathetic to the communities’ interests.

Argent’s approach to consultation also gained it considerable political capital. The value of this is not to be underestimated. In future, the development would need multiple consents and amendments, and a positive relationship with the council over the long term was essential.

One difficulty in assessing the degree of opposition to the scheme is that, by and large, only those who do object to some aspect of it will take the trouble to voice their views. That said, it is clear from the above that despite the extensive consultation process, the final scheme did not achieve complete consensus and that some disagreements remained, particularly on the balance between commercial and housing uses. These are picked up below in relation to the concerns of KXRLG.

King’s Cross Railway Lands Group

The King’s Cross Railway Lands Group (KXRLG) was an umbrella group of some of the resident, business, conservation and transport groups and had been a key opponent of the earlier LRC scheme (see Chapter 3). It provided the most vociferous, focused and enduring opposition to the Argent scheme, culminating in a judicial review of the planning approval in May 2007 (see Chapter 8). It pressed for an assortment of demands, but principally for higher levels of housing, particularly affordable units, and fewer commercial offices. Unfortunately, it was only possible to interview one member of KXRLG for this book. While Michael Edwards was reluctant to be the group’s sole source here, he notes that ultimately other members ‘were mostly deeply unhappy about taking part. The distrust of Camden officers among local community leaders remains very strong.’26 It is hoped, therefore, that the views of the wider group are fairly represented here.

The representativeness of KXRLG

Camden council’s planning officers did not believe that KXRLG was truly representative of the local community. Apart from a number of businesses, there was no resident community on the site.27 Had there been a resident community under threat, Camden council’s response to the opposition would have been very different. In the absence of one, the council’s primary concern was to engage with the wider community, and for this consultation to be inclusive and reflect the area’s true diversity.

This does beg the perennial question of who represents the community in planning negotiations. Camden council’s reaction to the opposition from KXRLG was shaped by the very nature of council politics. Councillors are democratically elected as the primary representatives of their community. They understand community politics, and those who do the job well act as a channel for local views. Some local ward members had concerns about the development, but these were not allied to those of KXRLG, and officers were never directed by their members to heed KXRLG above other voices. A number of its members were resident in other boroughs (not a reason to ignore their views, but councillors gave those views a different weight to those of voting Camden residents). In consequence, both Camden council and Argent met and consulted KXRLG on many occasions, but gave them no preferential status above other local interest groups.

Camden recognised that KXRLG was a voice in the community, but it was never recognised as the voice. Fairly or not, KXRLG was seen by many in the council leadership circle as politically marginal, and consequently it had limited traction with the elected members who controlled policy in the council. This forced KXRLG onto the political margins, forging relationships with smaller groups of councillors, including some on the development control subcommittee. This focused its influence at the decision-making, rather than the policy, end of the council hierarchy.

KXRLG could quite legitimately point to the fact that as an established umbrella group it was one of the most representative single organisations in the area. In 2002, however, the council established the King’s Cross Development Forum (KXDF)28 as an alternative umbrella group that might be more inclusive than KXRLG. By 2004 there were over 350 names on the mailing list for the forum, representing well over 100 organisations from Camden and Islington. Camden council took particular steps to include many of the hard to reach groups representing the Chinese, Somali and Bangladeshi communities, as well as local women’s groups. These had not been part of the KXRLG umbrella. Its support to the forum has since been commended in good practice

guides.29 Over 40 forum meetings were held over the course of the negotiations. The two groups were not mutually exclusive; in practice there was a good deal of overlap between their networks. The formation of the KXDF could be viewed as either a cynical attempt to counter KXRLG, or a genuine attempt to engage with local communities.

The reason for giving prominence here to the views of the KXRLG is that it was by far the most vocal group in opposition, and members held fundamentally different views regarding what should happen at King’s Cross. As suggested in Chapter 3, its views can be traced back to the campaigns against development in the 1980s and 1990s. At King’s Cross in the 2000s, it was employing similar arguments and tactics, but it was no longer campaigning against a disorganised council, or a developer that could be accused of riding roughshod over community views. Argent was intending to consult widely, and from first principles. Allemendinger30 makes the point that Argent and Camden council were committed to consensus and partnership-based regeneration, while the challenge by KXRLG was based on a more traditional approach to confrontational politics.

Policy constraints on the parameters of the debate

The parameter of the debate is a common problem in planning consultations. The presumption that there would be substantial commercial development on the site, close to the transport interchange at King’s Cross, was established before Argent St George had even been appointed. Strategic Planning Guidance for London, Regional Planning Guidance 3 (RPGC),31 published in 1996, had identified the King’s Cross railway lands as a site of national importance and as a major opportunity area for development. It suggested that a mixture of land uses should be accommodated, with the highest densities and most commercial uses closest to the rail termini. Camden council accepted this approach in Chapter 13 of its first Unitary Development Plan (adopted in March 2000). To have any substantial influence over the nature of the scheme, KXRLG would have needed to have influenced the council leadership early on, when discussions on policy for the revised Chapter 13 of the UDP started in 2001. In 2002, the report of the independent planning inspector on the amendments to Chapter 13 deepened the constraints on the debate:

By 2004, RPG3 had been superseded by policy in the mayor’s London Plan, which confirmed that King’s Cross was one of six opportunity areas in the central London sub-region, having ‘the best public transport accessibility in London’ and a central location, which offered ‘particular scope for high-density business development, as well as housing’.33

It could be argued that Camden council was at fault in not having spelt out the limitations of the debate more clearly when the consultations started. In practice, however, it is likely that to attempt to limit the debate in this way would have been provocative, divisive and hard to achieve. To most consultees, policy is highly abstract, and they do not necessarily feel constrained by it.

The political nature of the debate

The debate really concerned the nature of power in planning. While it is difficult to generalise about or to characterise the views of an umbrella group, some members of KXRLG believed that the development of King’s Cross should be based not on its potential contribution to London as a global city (through attracting financial services and corporate enterprises), but on its ability to serve local needs.34 Holgersen and Haarstad argue that the collaborative processes at King’s Cross were shaped and limited by institutions with a particular agenda. These institutions represented particular economic interests whose concern was the future of London as a viable business environment. By contrast, KXRLG was concerned about the future of London as a place to live.35 It was at a severe disadvantage from the outset in terms of its power and potential influence, since it neither set the parameters of the debate nor the process though which it took place.36 This severely constrained what the participation could achieve. Holgersen and Haarstad argue that such economic relations tend to be downplayed in the focus on consultation and consensus building.

By 2000 the interests of those who were concerned about the future of London as a viable business environment were firmly embedded in government policy. The need to balance local with London-wide and national needs always had to be a key issue for Camden council. The council acknowledged that a common response to their consultations was that ‘commercial office space should be reduced as a proportion of the development’.37 Offices were the obvious candidate for reduction if more space was to be provided for housing, community, leisure and recreation uses, all of which received strong support locally. However, without significant government intervention in the form of large-scale subsidy for public housing, or some form of land expropriation, a predominance of housing on the site was never a realisable proposition. Even if the council had conceded to such demands for a predominance of affordable family housing, it would not have been supported by either national or London planning policies.

Argent itself was constrained by the need to provide a return to the landowners and its board. When land is owned, developed and financed privately and the landowner retains the right under law to enjoy their land, planning can never be an open exercise. The landowners had every right to maximise the value of their land within the confines of planning policy. If there is criticism of major schemes as being foregone conclusions, then this is partly correct. Such demands from local groups cannot be delivered within the present system.

The establishment of a community development trust

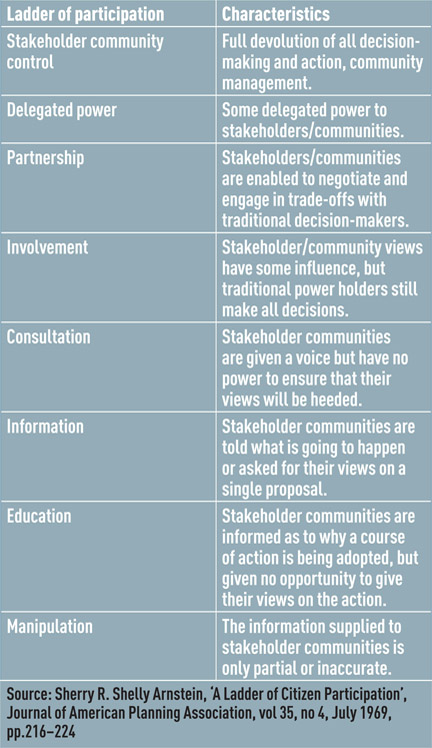

The only other way in which the community could have had a wider role in shaping the King’s Cross scheme was if some or all of the land had been transferred into community ownership (at the top of Arnstein’s ladder – see Table 7.1 on p.148), as had happened in Coin Street.38 One of the KXRLG’s demands was the establishment of a Land Trust or Community Development Trust. As Michael Edwards states:

Given the way in which the ownership of the King’s Cross lands by LCR was tied into the development of Eurostar this was never a possibility. The gift would in any case have been in the hands of central government.

The problem of ‘consensus-building’ processes in the face of ideological differences

The real question is whether the planning system in general, and consensus building processes specifically, can deal with such fundamental differences in view. Successive governments have proposed partnership and consensus building approaches for the delivery of urban regeneration schemes. However, as Allemendinger argues, consensus on deep ideological differences is impossible to reach, and the present planning system is not a suitable vehicle for handling fundamental differences in ideology.40 The debate also becomes semantic. If consensus means reaching ‘a general agreement’, those who disagree will inevitably claim there is no consensus. In these circumstances, the focus on consensus building had no real end point. The objectives of Camden council and KXRLG were very different and the debate was in many ways more about how the system should work than the outcomes. This is not to devalue the role or views of KXRLG, it is just that the system within which Camden council was operating was unable to deliver the outcome that they desired.

KXRLG’s criticism of the consultation process The level of participation

Given the strong views held by KXRLG on the proposed development at King’s Cross, it is not surprising that the group was also highly critical of the consultation processes that took place.

Not being part of the process, but observing it from the outside, KXRLG considered that Camden’s planning and vision documents seemed to reflect far too closely those of Argent, both in their timing and their content.41 This observation was, of course, entirely correct. The negotiation process was based on the principle of convergence. It was inevitable, therefore, that the processes were triggered by common milestones and that the emerging documents were coordinated to ensure that they were compatible. To KXRLG, however, it felt as though the council was doing exactly what Argent wanted.42

Michael Edwards felt that Argent’s consultation process was ‘highly manipulative’, having been carried out entirely within the constraints of what the developers wanted to see on the site. He likened it to ‘re-designing deckchairs on the Titanic’.43

He expands these views in more recent writing:

Edwards felt it would have been more appropriate if Camden council had undertaken a consultation process that was more along the lines of that carried out in 1990–91 on the LRC scheme. In other words, KXRLG wanted to be active participants or partners rather than consultees.

The arguments about the nature of the consultation process deserve further exploration. Shelly Arnstein’s eight levels on a ‘ladder of participation’ (Table 7.1) are helpful.

Camden council and Argent would probably argue that they were offering a level of participation that lies somewhere between consultation and involvement, and that they did their upmost to ensure that this was as comprehensive and inclusive as possible. As explained in Chapter 4, they were extremely careful to ensure that they were the only two parties at the negotiating table; this is one reason why ‘partnership’ on Arnstein’s ladder of participation was never on offer. They wished to retain tight control over what would be a difficult process, and one that could easily have become bogged down in debates on fundamental differences in the vision, or legitimate but unachievable community objectives.

Briefing of members of the development control subcommittee

Michael Edwards was also critical of the inadequacy of members’ briefings on such a major planning application and the way it was considered in committee.45 He is entirely correct here. Councillors clearly need sufficient time and knowledge to be able to consider a complex application in stages from basic principles to detail, and this is normal practice. The reasons for, and near catastrophic effects of, the lack of briefings for members of the development control subcommittee on the King’s Cross scheme are explained in depth in Chapter 8. Essentially the chair of the subcommittee refused any briefing, apparently believing that it could prejudice the independence of the decision-making process.

Interestingly, Argent’s Robert Evans also argues strongly that committee members must be involved earlier and more systematically if they are to reach informed decisions. Argent has even commissioned research in support of this idea.46 If community involvement is front-loaded, then it is only logical that the decision-makers must be involved early as well, if they are to avoid being put at a disadvantage. This view was supported by the 2006 Barker review of planning.47

Conclusions

Both Camden council and Argent put considerable time and resources into public consultation. The exercises were extensive, prolonged and systematic, and Camden council’s efforts to engage with hard to reach groups still equate to best practice. Given the extent and duration of the consultations, it is perhaps not surprising that there were complaints of consultation fatigue at King’s Cross. Camden council and Argent were talking to the same groups about the same things for almost six years. Recent guidance suggests that there could be merit in local planning authorities and developers consulting together to reduce the danger of fatigue.48 This would certainly be more cost efficient and might be a logical next step in the process of partnership working. However, it would undoubtedly cause further distrust among those with a deep ideological mistrust of developers, and would certainly strengthen any perceptions that the relationships between local planners and developers are becoming far too cosy.

The consultations contributed significantly to the knowledge base that underpinned and shaped the scheme, and in this sense did have a fundamental influence on it. It may have resulted in some major changes, and tangibly shifted the agendas of both parties, strengthening Camden council’s hand in the negotiations. Had there

been widespread and deep-seated opposition to the scheme, Camden council would not have been able to ignore it and a refusal would have been inevitable. The evidence from the consultations would then have been a major weapon in fighting Argent at appeal.

While public consultation helped to improve the scheme, in the view of Argent’s Robert Evans49 it did not avoid unnecessary objections being made at a later stage, nor did it save any time – the government’s two main arguments for pre-application consultations by developers.50

The applications were still greeted by some vociferous objections, notably from KXRLG. And it still took nearly two years for the final application on the main site to receive planning permission. The judicial review that KXRLG sought on Camden council’s decision to grant planning approval for the main site occupied a further six months, and was followed by a public inquiry on Islington council’s last minute decision to refuse planning permission for the ‘Triangle’ site (see Chapter 8). The public inquiry and judicial review cost over £4 million.51 The entire process following submission of the applications took four years and two months. Commenting on the process somewhat wryly, Evans felt that it was Argent’s own lengthy process of consultation that gave the opponents the opportunity to gear up. The inevitable conclusion is that community consultation cannot build consensus when deep ideological differences mean that the nature of the debate is highly polarised.