3.

History and Development Context

This chapter provides some historical background on the King’s Cross area to set the stage for Argent’s present development. It covers the area’s industrial heyday and subsequent decline and then considers regeneration attempts in the 1980s (associated with the decision that King’s Cross station would be the Channel Tunnel high speed rail terminus) and the community opposition that these engendered. It then considers the construction of the high speed Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL) into the terminus at St Pancras, and other rail infrastructure projects that were underway at King’s Cross St Pancras. It concludes with an explanation of the process through which Argent St George was selected as the developer for the King’s Cross site. A timeline to clarify the historical development and complex period of overlapping infrastructure projects can be found on pp.viii-xi.

The History of the King’s Cross Area

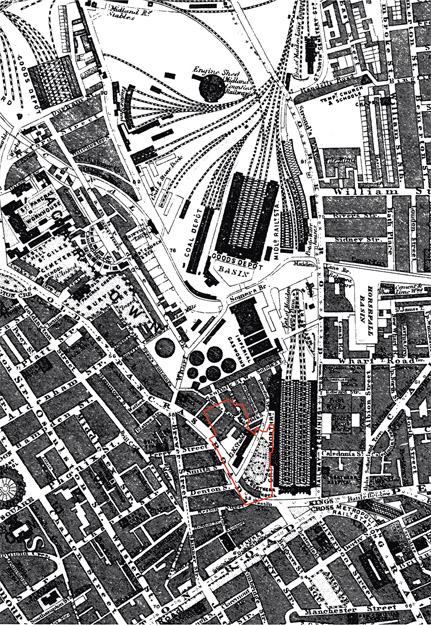

Figure 3.1:

King’s Cross before the railways (1834).

Historically, what is now known as the King’s Cross area was the low-lying and marshy edge of the early City of London where the dispossessed lived and worked on the fringes of society. Rocque’s map of 1769 shows a smallpox hospital and later a fever hospital on the site of King’s Cross station.1 In close and unhealthy proximity to the hospital was the Great Dust Heap, a mountain of ash, bones and other rubbish picked over by scavengers from the locality. It was finally cleared in 1848 to make way for the construction of the railway.

Despite the expansion of London in the 18th century, King’s Cross remained largely rural. It was the completion of Euston Road in 1756 that led to the development of the first permanent occupation of the area, low quality, two-storey terraced houses on the southern part of the King’s Cross site.

The 19th-century industrial heyday

As London grew, so did the demand for food, fuel and building materials. The Regent’s Canal, completed in 1820 (Figure 3.1), linked King’s Cross to Birmingham and the new industries of the Midlands. It crosses the centre of the King’s Cross site and remains in use today, albeit for leisure purposes. Urbanisation brought workers’ tenements, a gas works supplied with coal by canal, and soon afterwards more industry and then the railways. In 1830, in a move to improve the area’s poor image, a statue of King George IV was erected at the Battle Bridge crossroads (now Euston Road, York Way and Gray’s Inn Road). The design was vulgar and it immediately attracted ridicule. Although it was demolished in 1842, the new name for the area, ‘King’s Cross’, stuck.

Whereas the railways in south and east London (Charing Cross, Waterloo, Fenchurch Street and Liverpool Street) penetrated right to the edge of the city, the owners of valuable property in north and west London lobbied successfully to stop railway construction south of the Euston Road. King’s Cross, Euston and later St Pancras stations were consequently confined to the poorer neighbourhoods on the northern city fringe (Figure 3.2). This did not lessen their impact; in 1866 the construction of St Pancras resulted in the demolition of 4,000 houses and displaced around 12,000 people.

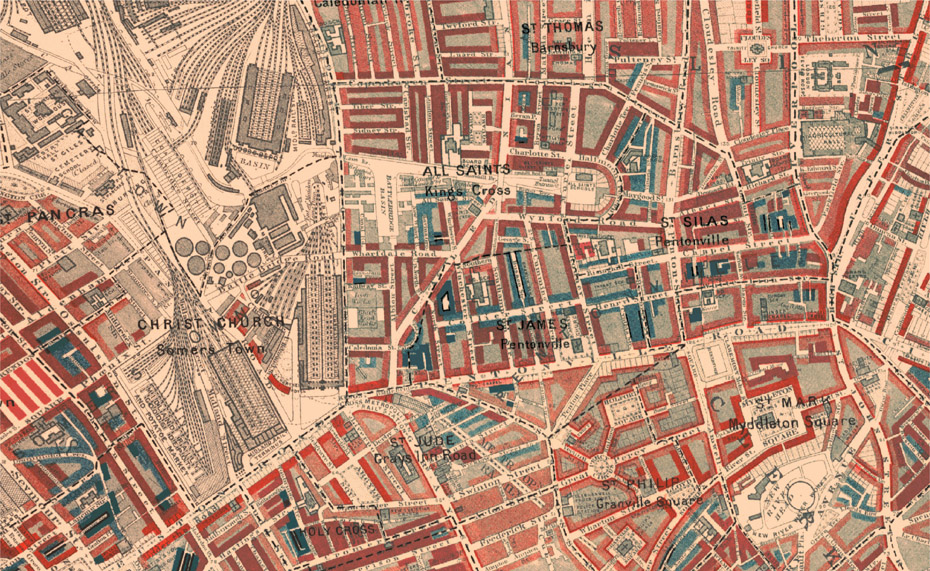

Figure 3.2

King’s Cross before the construction of St Pancras station (1862).

The Great Northern Railway (GNR) purchased land at King’s Cross for a station, goods terminus and steam locomotive depot. The present station, built in 1852 (Figure 3.3), and the Great Northern Hotel, built in 1854 (Figure 3.4), were both designed by Thomas Cubitt. King’s Cross station was soon joined by that of the rival Midland Railway at St Pancras. Designed by William Barlow and built between 1866 and 1868, the single span roof (Figure 3.5) was one of the wonders of Victorian engineering. The Midland Grand Hotel (Figure 3.6), designed by George Gilbert Scott, was completed in 1876. The stations were built separately by private companies that were in competition with one another; there was no planned interchange. Indeed, looking at the stations today, it is clear that they are not only very different architecturally, but that they almost deliberately turn their backs on one another. It was only with the coming of the high speed rail links into St Pancras 125 years later that this problem was finally addressed.

Figure 3.3: King’s Cross station and the Great Northern Hotel (c.1900).

As London’s population increased in the 19th century, so did congestion. The Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground railway, was completed in 1863 to address this, and linked the main line railway termini at Paddington, Euston and King’s Cross. By the latter part of the 19th century, King’s Cross had become a major goods transport interchange, bringing food, fuel and raw materials from the north of Britain and

Figure 3.4: The Great Northern Hotel (c.1890).

Figure 3.5:

The restored roof of the Barlow canopy at St Pancras station (2016).

Figure 3.6:

The Midland Grand Hotel, St Pancras.

Figure 3.7: The Granary complex and Regent’s Canal (1999) depicting the gasometers and Culross Buildings (bottom right).

trans-shipping them by barge and horse and cart for distribution around London. Behind the stations a number of important buildings were constructed. These included the Granary Building (1850–52), again by Cubitt (Figure 3.7), and the Eastern coaldrops (1851) and Western coaldrops (1860s). Meanwhile, ever expanding rail traffic saw further buildings constructed, including Stanley Buildings (1864–65), to provide affordable housing for railway workers; several new gasholders (1880–1900) and the German Gymnasium (1864–65), a club and sports facility for the German Gymnastics Society.

The transport and goods depots needed low wage labour and the construction of low quality housing followed. The areas immediately around King’s Cross became home to an urban underclass. To the west of King’s Cross, Somers Town slipped steadily into decline and makes an appearance as a poor neighbourhood in a number of Charles Dickens’ novels, including The Pickwick Papers, Bleak House and David Copperfield. In response, the Bedford Estates, south of Euston Road, erected gates to keep out the undesirables, cementing the social divide across Euston Road. This is illustrated in Charles Booth’s 1898/99 map of poverty in London (Figure 3.8).2 The lowest three categories of social strata in Victorian urban society were classified by Booth as: ‘poor’; ‘very poor, casual, chronic want’; and ‘vicious, semi-criminal‘. These three categories occupied most of the surrounding area.

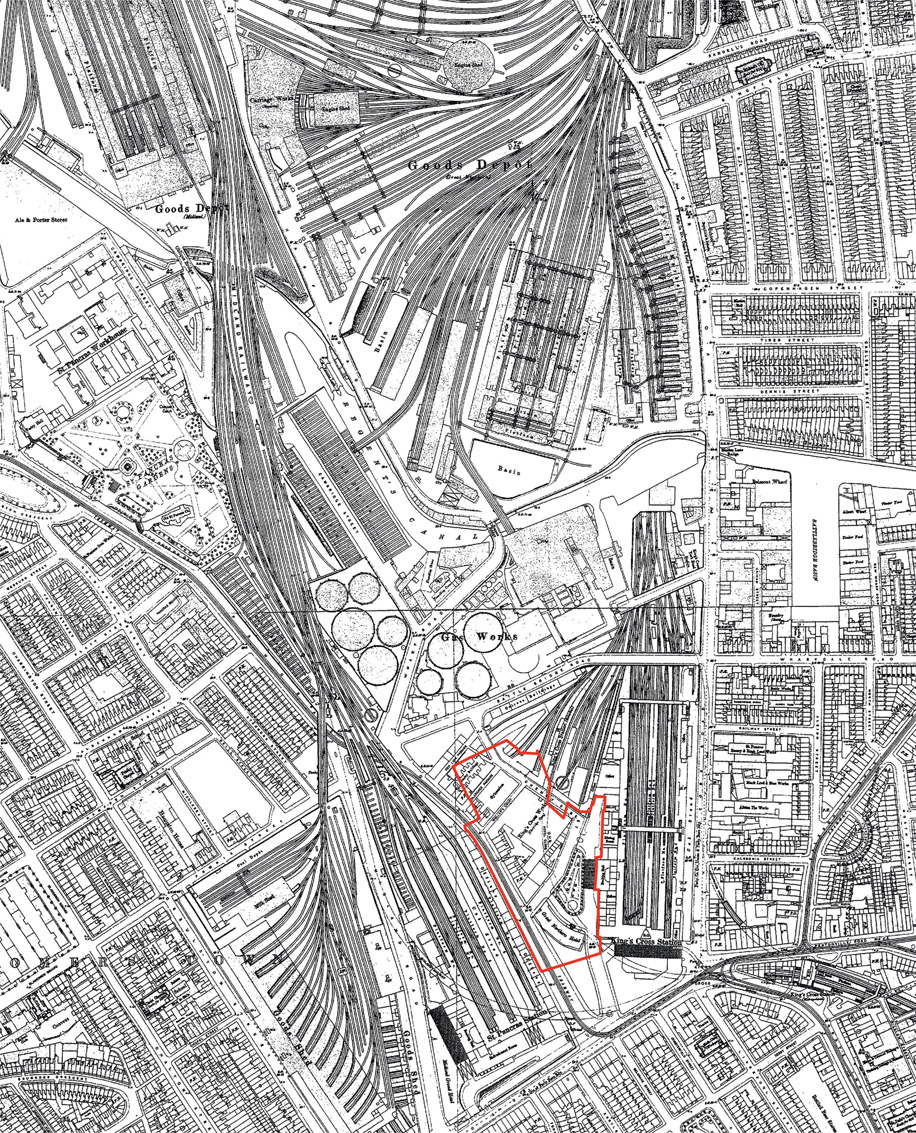

By the beginning of the 20th century, the area was a mass of stations, sidings, railway buildings and related warehouses. The two stations were the gateway into London for commuters, visitors and immigrants, as well as for goods from the north of England and Scotland. It was busy, congested, dirty, but efficient. The adjacent neighbourhoods housed the working poor and the destitute. It was not an attractive place, but it worked (Figure 3.9). And as intended by the Duke of Bedford, it stopped firmly on Euston Road, a boundary between rich and poor that was to endure for over a century.3

The 20th-century decline

For the first half of the 20th century, King’s Cross continued to function as an unloved but essential part of the London economy. The stations became dirtier, gloomier and seedier. The spaces around them filled with kiosks and bus stands, and the once grand railway hotels went downmarket. In the aftermath of the second world war, the nationalisation of the railways in the 1947 Transport Act meant that the land passed into public ownership. With the switch to

Figure 3.8:

Booth’s Map of Poverty in London (1898–99). The housing shaded dark blue and black was occupied by the ‘vicious and semi-criminal’ classes.

Figure 3.9: King’s Cross at the height of the railway age (1894).

containerised rail freight, the King’s Cross goods hub effectively became obsolete. In the southern part of the goods yard, most of the rail lines were lifted in the 1980s. The area ceased to be a busy industrial and distribution centre and land and buildings became vacant and derelict. The loss of jobs had a serious impact on local communities and social deprivation increased. By the 1980s, the area around King’s Cross station was notorious for crime, prostitution and drug abuse, a reputation that further dissuaded investment. The railway lands became largely vacant, but provided cheap workspace that attracted artists and clubs and its own sub-culture.

The first signs of tentative development interest appeared in the Balfe Street area to the east of King’s Cross station – an area of residential streets and eclectic 19th-century industrial buildings.4 The area had been allowed to deteriorate by the owner, Stock Conversion and Investment Trust, in the expectation that it could be comprehensively redeveloped for offices. Residents fought the redevelopment plans, and in 1977 succeeded in getting it designated as a conservation area, thus saving it from demolition. This and subsequent campaigns5 represented the emergence of a vocal and organised community opposition.

Conditions for change

Figure 3.10: St Pancras gasworks in the 1950s.

In the post-war period there were a number of changes in the ownership of the railway lands that would have an important impact on its future development. In 1969, the British Railways (BR) Sundries Division (which managed its property assets) was hived off into a separate government owned entity, the National Freight Corporation (NFC), and with it went ownership of the central area of the King’s Cross site (around Granary Square). The remainder of the site was retained by BR, effectively splitting up the strategic land holding. This was followed in 1982 by an employee buyout of NFC and the site passed out of public ownership into Exel logistics. Roger Mann, previously head of property at BR and NFC, transferred into Exel, became managing director of its estates division, Hyperion. The investment climate in London was changing, regional policy was being relaxed and government restrictions on office development were eased. With deregulation of the City on the horizon, the property market sensed a coming boom.

First Regeneration Proposals

The first tentative discussions about developing King’s Cross came in 1984. Hyperion was approached by Godfrey Bradman and Stuart Lipton from the company Rosehaugh Stanhope, which was building an impressive reputation as a developer in the City of London following the 13-hectare redevelopment of Broadgate, the largest office development in London until the arrival of Canary Wharf in the early 1990s. The catalyst for their approach was the government’s decision to commit to the construction of the Channel Tunnel and high speed rail links from Folkestone into London. The ambitious plan in 1987 was to construct a £1 billion new terminus, beneath the existing King’s Cross station.

The London Regeneration Consortium plc (LRC) was formed as a joint venture between Rosehaugh Stanhope and British Rail. The terminus beneath King’s Cross station would be cross-subsidised through developing the 120 acres of goods depots and sidings north of King’s Cross. Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) and Norman Foster were appointed as separate masterplanners in a star team that included Frank Gehry and David Chipperfield.

In a confidential memorandum from September 1987,6 LRC noted that the development offered the opportunity for significant cash receipts but that speed was of the essence if the development was to hit the property market before other large schemes, Canary Wharf in particular. Camden council was broadly supportive, seeing the advantages of regeneration and new housing. The expectation was that planning approvals would be granted within six months, with development commencing soon after in the summer of 1988. This proved to be an optimistic assessment.

The plan to bring the CTRL into King’s Cross was perceived as a renewed threat to the area east of the station, and some of the community groups that had opposed the Balfe Street proposals joined forces in opposition as the King’s Cross Railway Lands Group (KXRLG).7

The opposition groups rejected the findings of a House of Lords committee (September 1987) that King’s Cross station should be the terminus for CTRL and maintained that St Pancras would be the better terminus. In this respect their views were ultimately vindicated (1993).

After extensive public consultation, Camden council published a Community Planning Brief in 1988. This set out requirements for housing, training facilities, open space and industrial floor space, but set no upper limits on the quantum of development. The housing envisaged was predominantly low rise family accommodation at a density of around 70–110 habitable rooms per acre (hra).8 The LRC recognised that the community was apprehensive about the scheme,9 but its approach to consultation was more of a marketing process than genuine engagement with the community.

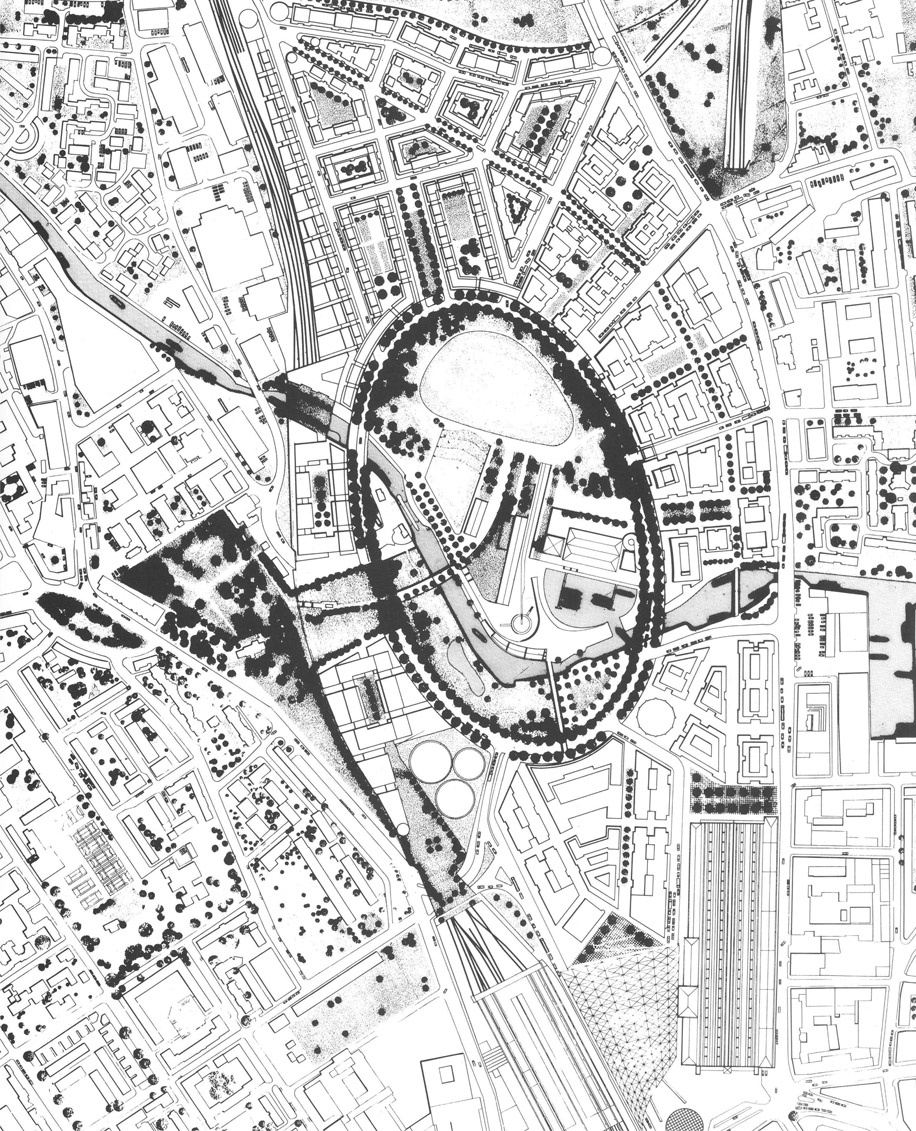

Figure 3.11: London Regeneration Consortium proposals from SOM masterplan (1989).

Figure 3.12: London Regeneration Consortium proposals from Foster’s masterplan (1989).

A planning application was submitted by LRC in October 1989. The scheme envisaged almost 12 million square feet of development, of which nine million would be commercial and 1.7 million housing. Under the SOM masterplan, the proposal was to deck over the railway tracks (using the consortium’s experience at Broadgate) and to develop large floor plate office buildings along York Way and between the two stations. The majority of housing was to be located to the north of the site within a grid of streets and squares. The centre of the site was designed around a linear park and a set of new canals that created a moated mixed-use area. Within this sat those historic buildings that were to be retained, in a plan that could best be described as ‘picturesque’. The proposed building heights were four to ten storeys with no significant tall buildings (Figure 3.11).

The Foster masterplan took a different approach. It still decked over the tracks and concentrated the commercial floor space to the south, with housing to the north. Here, however, it proposed perimeter blocks on a street grid enclosing private spaces. The radical difference was an oval park in the centre of the scheme around the canal. Here the few historic buildings that were retained would be standalone museum pieces (Figure 3.12). Sir Norman Foster also proposed a new station between King’s Cross and St Pancras on the site occupied by the Great Northern Hotel (Figure 3.13).

The development was structured so that the landowners would receive their existing use values plus the development uplift after LRC had taken its costs and a developer’s profit. The valuation was to be based on an assessment of each land parcel once planning permission had been granted. For British Rail, this amounted to a projected profit of £155–£466 million (at 1987 prices), and with an anticipated 7 per cent rise in rents, this would increase to between £461 million and £1 billion.10

The scheme started to run into difficulties on a number of fronts. The station box beneath King’s Cross station was a huge technical challenge and presented a considerable financial burden for the scheme. With the benefit of hindsight, it is also clear that British Rail was inexperienced in property development and this role was subservient to its railway operations remit. Although the LRC had engaged with, and achieved the support of Camden council, it had underestimated the power of the local community. In an era of radical local politics where community development projects such as the Coin Street Community Builders on London’s South Bank11 were established as workable precedents, attempts to ‘sell’ the LRC scheme locally did not wash. Community opposition influenced the council and delayed the process, eventually pushing it into the unstable times of the 1990s recession. For a developer, a sound working relationship with a council depends on

stable internal politics. At the time, Camden was financially and politically unstable. It was in crisis and easily influenced by a determined and well networked local community. The development consortium had failed to understand this.

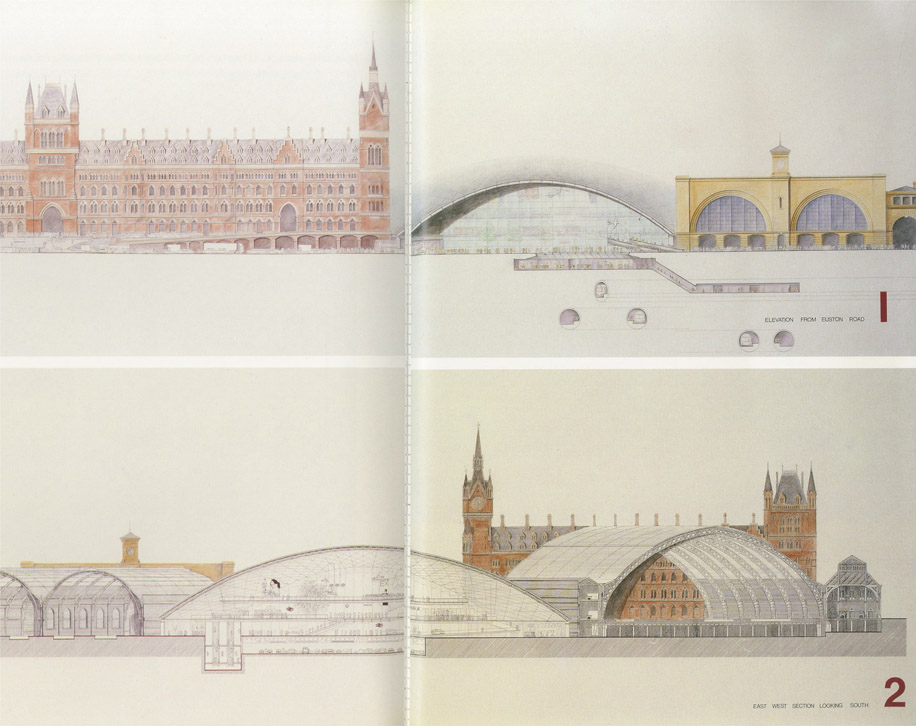

Figure 3.13: Proposals for new station concourse at King’s Cross (1989).

The London property boom, stoked by the Thatcher government’s policies of deregulation, peaked towards the end of 1989, and then collapsed. The council’s environment committee determined in July 1992 that it was ‘minded to grant’ outline planning permission if a number of significant matters could be resolved, but time was running out. Progress was halted when British Rail abandoned plans to bring the CTRL into King’s Cross and in March 1993 the government announced its preference for a CTRL terminus at St Pancras.12 This decision coincided with a major economic downturn. Many property firms were seriously exposed, and a number, including Rosehaugh Stanhope, went into receivership. The King’s Cross deal collapsed. In total some £52 million had been invested in the scheme without any return.13

Although the LRC scheme collapsed, it left a significant legacy in terms of local community politics. KXRLG and other groups had engaged and brought forward alternative views of how King’s Cross might be developed.14 They had also developed a close and cooperative working relationship with Camden council. In the words of Michael Edwards of KXRLG, the group ‘worked with sympathetic councillors and officers (with grant support from Camden) and the combined effect was – in hindsight – a fairly effective episode in consultation, if not full participation’.15 Later, when the Argent scheme emerged, KXRLG had strong views about the site and may have hoped that these would be given the same prominence by Camden councillors and officers.

The King’s Cross Partnership

For the time being, the King’s Cross site lay dormant again and was occupied by a range of low intensity temporary uses. During the 1990s a more business-oriented culture had entered government, joint public/private ventures were the preferred way forward and this culture had percolated down to local authority level. Activism through pressure groups was being replaced by more formal partnerships embracing local residents’ groups and other stakeholders, including local health authorities, businesses and the police.

The government’s Single Regeneration Budget (SRB) programme marked a departure from the distribution of regeneration funds based on measures of relative deprivation. Instead, funds were allocated to public/private partnerships on the basis of clear investment and regeneration objectives. In response, the King’s Cross Partnership (KCP) was set up in 1996. The founding partners were the London Boroughs of Camden and Islington, and the two railway companies – Railtrack and London and Continental Railways (LCR) – were appointed as the consortium that would construct and run the new high speed rail link to the Channel Tunnel. It also included community representatives and other public sector bodies. The partnership bid received £37.5 million from the government for a seven-year programme of work starting in April 1996.

The KCP board was chaired by Sir Bob Reid, chairman of the British Railways board from 1990 until 1995. Its explicit objective was to bring forward investment programmes that would prepare the local area for the anticipated regeneration, and increase opportunities for local people. Part of its money was spent on training and education but in the absence of any specific development proposals, most of its effort was devoted to changing the image of the area through promotional material, improving housing estates, streets and open spaces, and implementing measures to combat crime. Perhaps its greatest legacy, though, was the working relationships that it helped to develop between the key organisations and institutions in the area. Crucially, the KCP provided a vehicle for dialogue between stakeholders and a sounding board through which difficult issues on King’s Cross could be aired. It also built close relationships with the Government Office for London (GOL).

Figure 3.14: Channel Tunnel Rail Link infrastructure and site boundaries.

Rail Infrastructure

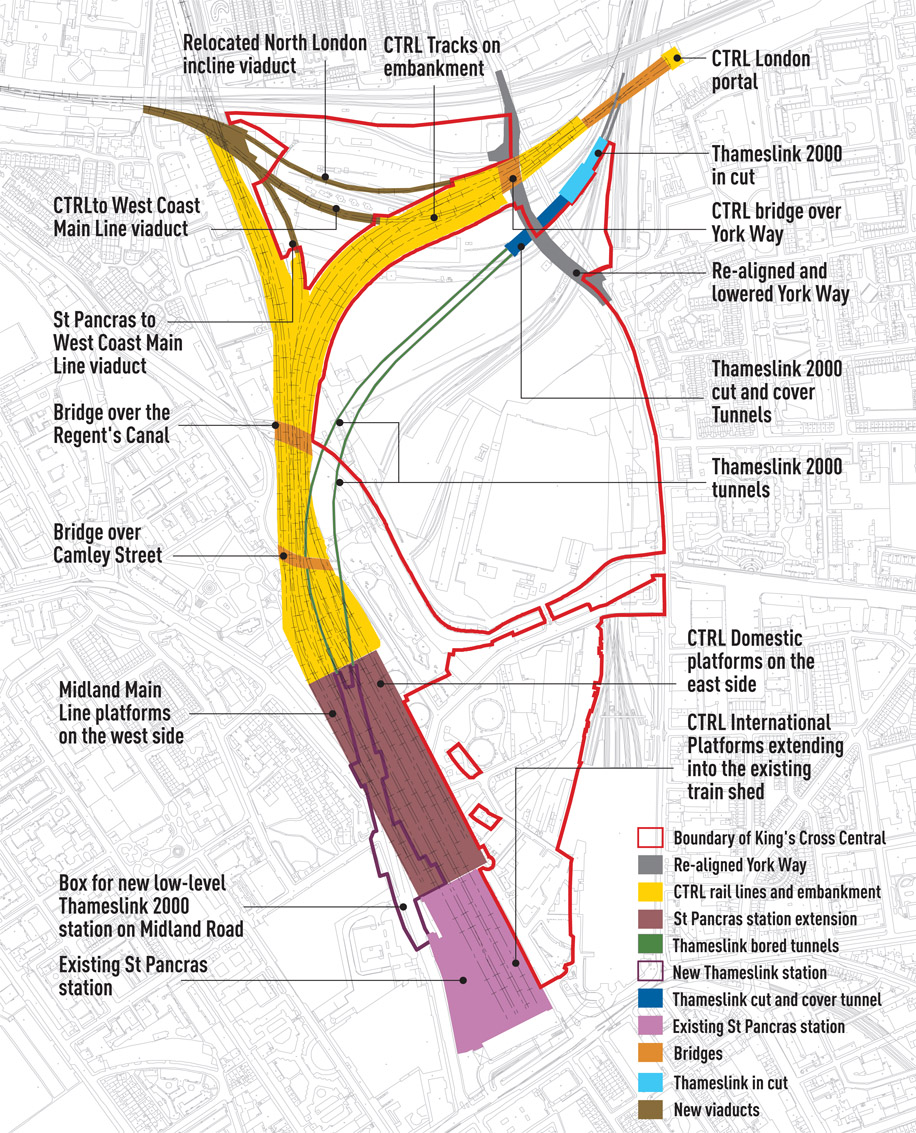

The development of the King’s Cross railway lands was tied intricately to the construction of the CTRL into the terminus at St Pancras, and other rail infrastructure projects (see Figure 3.14).

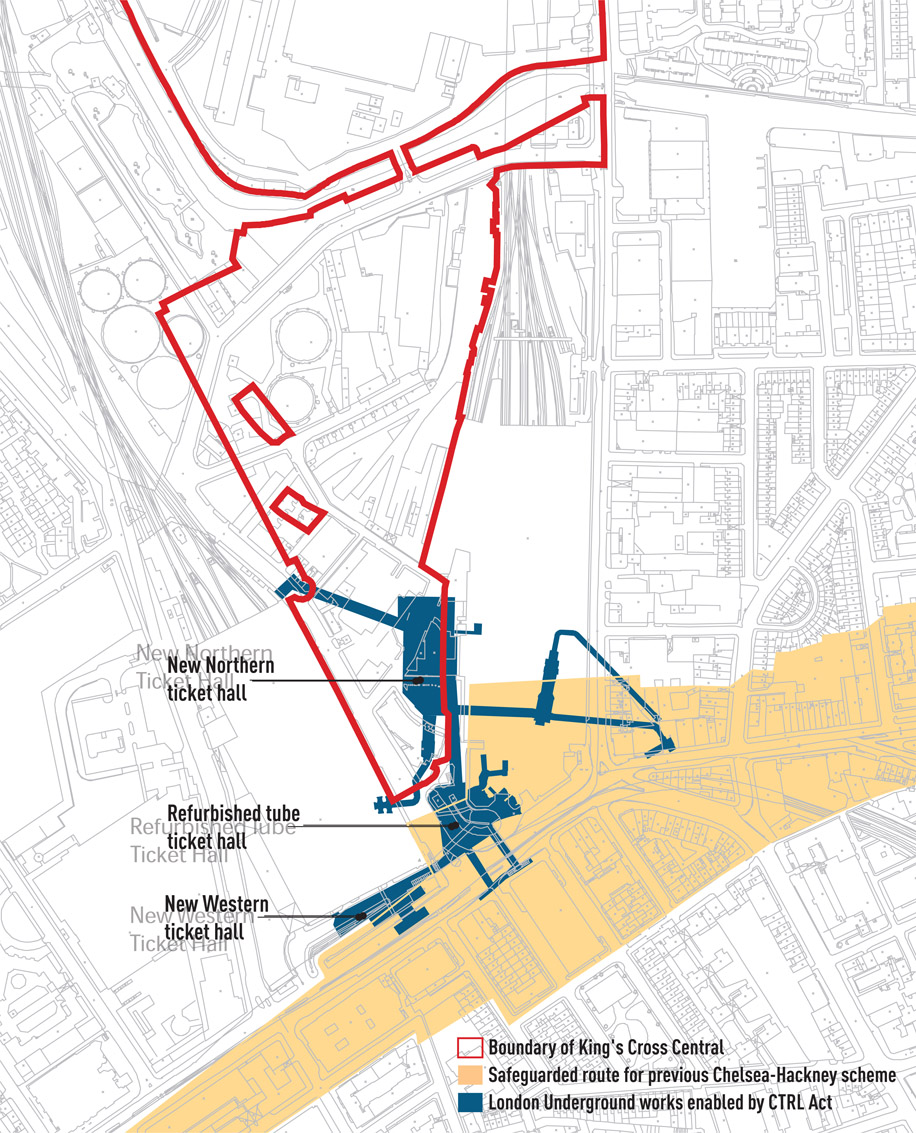

The King’s Cross underground concourses

Following a fire at King’s Cross station in 1987, a decision had been taken by the government to invest £774 million in the renewal of the King’s Cross underground concourse. Designed by Arup, this complex reconfiguration of the ticket halls and concourses improved safety, increased capacity and helped to create the passenger capacity needed for the increased footfall through the stations when St Pancras was eventually chosen as the terminus in central London for Eurostar trains (Figure 3.15). The works also created the additional capacity that would benefit the future development of the railway lands. It is common practice in the UK for developments to be required to pay for any transport improvements that they may necessitate. Potentially, this government funding liberated the development of the railway lands from what might have been a considerable financial burden for transport improvements.16

The Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL)

In March 1993, after much deliberation, the government accepted the case for a high speed line through north Kent and via Stratford into St Pancras (Figure 3.16). This was duly authorised in the CTRL Act 1996. In accordance with the new orthodoxy of government policy, a public-private finance initiative meant that the risk of building and operating the new railway would be transferred to the private sector in return for future fare revenues. Part of the contract arrangement included land at King’s Cross and Stratford, which the government retained after railway privatisation in 1993.17 The government decided to use that part of the King’s Cross site still in its ownership to offset some of the development costs of the CTRL. Under this arrangement, the government would recoup the pre-agreed land base values, but the development uplift would be retained by the operator.18 The basis of the government tendering arrangement was that private finance would be raised through debt and equity to build the railway. In consequence, this expenditure would be ‘off balance sheet’ and would not impact on tight government spending restrictions. The government tender to construct and operate the railway was won by LCR.19

St Pancras station and Chambers

The CTRL would run from Stratford under the existing North London Line (now the overground) and emerge from a tunnel at the north of the King’s Cross site onto an embankment leading to a new upper level terminus at St Pancras.20 Sir Norman Foster was selected to extend and redesign St Pancras station. The Foster plan moved the existing Midland mainline platforms to the side, constructed a large extension to the rear of the station with platforms over 400 metres long to accommodate the Eurostar trains, and placed the ticketing and retail facilities beneath in the old station undercroft. Work on stage two of the CTRL works, which included St Pancras station, began in July 2001.

Figure 3.15: King’s Cross underground concourses.

Financing CTRL and the Interchange

It was possible to calculate the construction costs of the CTRL in advance, but the unknown variable was the operating revenues. Subsequent changes in the revenue streams, due partly to the advent of cheap airfares, significantly reduced the income forecasts of Eurostar. The debt required ballooned, banks backing the consortium withdrew their support and in 2003 LCR had to go back to the government and ask for a further £1 billion. With the project in jeopardy, John Prescott, then deputy prime minister, intervened and pushed the problem back to government departments to solve. Initially, there was talk of selling the King’s Cross landholdings, with Argent novated as developer. However, LCR persuaded Prescott that the land would be worth far more if held for the long-term. Without Prescott’s agreement that LCR should retain the land, the development under different ownership would probably have been substantially different.

An internal deal was finally brokered between the office of the deputy prime minister and the Treasury, who agreed to guarantee the loans. The condition was that some of the shares would be handed over to the government once the railway was finished and thus LCR would effectively become a government-owned company.21 This unlocked the problem, but put the expenditure back ‘on balance sheet’, a state of affairs that was contrary to government policy and for which MPs and the chancellor (Gordon Brown) in particular, were apparently unaware. When this agreement was unearthed in 2004 by a government select committee, uproar ensued and the chancellor subsequently withdrew funding from (and therefore suspended work on) the underground concourses and City Thameslink station.22 With work on the interchange suspended indefinitely, the southern part of the King’s Cross site could not be completed. This impacted on the transport assumptions underpinning the scheme and potentially on investor confidence. To compound the problem, LCR had been subcontracted to build the City Thameslink station box, but the £60 million for the fit-out was also frozen. For more than a year there was no certainty as to when the City Thameslink station would become operational. Fitting-out the underground station at a later date would have required land in King’s Cross being set aside for future working areas, with all the associated blight. Intensive lobbying from LCR, Camden council and Argent failed to resolve the problem. It was only when London won the bid for the 2012 summer Olympics in June 2005 that funds were released by the Treasury and work could resume. The implication of this decision is picked up later in Chapter 9.

LCR’s stations and property managing director, Stephen Jordan, came from a marketing and development rather than a railways background. As a shrewd and well-connected operator, Jordan was to play a pivotal role in the development of the railway lands. He had a detailed knowledge of the area and its opportunities, and brought a strong personal ethos of consensus-building to the development process. He actively engaged with Camden and Islington councils, English Heritage and local communities through the KCP (see p.31), and helped to build long-term relationships that were invaluable in subsequent negotiations on the development of the railway lands. He saw stations not just as transport interchanges, but as gateways that set passenger expectations. When executed well, he understood that they could also be valuable property assets. A team was assembled that studied and visited stations in Europe and the United States with the objective of making St Pancras ‘as good as we could make it’.23 To ‘celebrate’ the experience of the railway, LCR was therefore prepared to invest considerable sums of money to restore the Victorian magnificence of the station. Foster’s design restored and revealed the grandeur of the Barlow station and canopy in a spectacular fashion and St Pancras station was formally opened as the Eurostar terminal in November 2007.

Figure 3.16: King’s Cross in 1999. View of the stations looking northwards.

Originally, St Pancras Chambers (the grand Victorian hotel in front of the station), was not included in the railway package as the government was nervous of the potential costs of refurbishing the Grade I-listed building, by now in a state of severe disrepair. After winning the contract, however, LCR insisted on its inclusion, seeing it as the vital ‘front door’ to its project. Control of the hotel also allowed a comprehensive restructuring of St Pancras to occur, and maintained the integrity of LCR’s landholdings.

The refurbishment of the hotel presented considerable problems due to poor internal circulation and awkward room configurations. LCR mounted an open competition to find partners to carry out the refurbishment, and it was awarded to Manhattan Loft Corporation. Its proposals were to extend the hotel on the west side of the station to provide additional rooms and facilities commensurate with the requirements of a five star hotel. The upper floors, which were difficult to reuse as hotel bedrooms, were to be converted into upmarket loft apartments. The hotel plans were approved in 2005 and it opened in 2011.

Figure 3.17: King’s Cross in 1999. View of the stations looking southwards.

To complete the interchange, the Thameslink services were to be upgraded and the cramped station on Pentonville Road moved to connect

directly into St Pancras. As a result, St Pancras and its Eurostar services would be connected directly to Gatwick and Luton airports.

Coordinating the transport projects

This substantial investment in transport infrastructure was implemented by three independent companies under separate contracts: LCR was constructing the CTRL terminus at St Pancras, Network Rail the new King’s Cross Thameslink stations, and London Underground Limited (LUL) the new underground concourse. Close project liaison arrangements were put in place. However, London’s successful bid for the 2012 summer Olympic games in July 2005 brought a need for more formal coordination mechanisms to ensure that the concourse at King’s Cross, the central London terminus for the games, could be completed in time. This issue is picked up in Chapter 9.

Completing the Site Assembly

With the appointment of LCR, the landholdings at King’s Cross passed out of government control into private ownership (Figure 3.16 and 3.17). In order to complete the site assembly, LCR approached Exel’s property wing, Hyperion, owners (as described earlier) of the central part of the site. The orthodox approach to land valuation would have been to employ large teams of surveyors to agree the relative values of the land as yet undeveloped for unspecified uses. Alternatively, the valuation could be postponed to some time in the future. LCR and Hyperion both recognised the difficulties of this. There were simply too many unknowns (particularly site preparation and decontamination costs), to come to an accurate or meaningful valuation of the two parcels of land. Yet leaving the valuation to the completion of the scheme could have caused internal rivalry, with both parties attempting to manipulate the masterplan in order to maximise the values of their respective sites.

Fortunately, Stephen Jordan of LCR and Roger Mann, director of property at Exel/Hyperion, had previously worked together in the early days of the National Freight Corporation. They left their advisers to argue respective valuations, withdrew to a wine bar and thrashed out a deal.24 As so often in the negotiation process for the development, trust between the individuals involved was crucial. Jordan and Mann agreed to apportion profits purely in accordance with the percentage of landholdings each put into the pot, with LCR taking a 5 per cent fee as project managers. As a safeguard, the partners appointed an independent arbiter to act in the event of any dispute. He was briefed monthly but was never used. This pragmatic solution was based on a belief that ultimately the value of both of the landholdings would be maximised by getting the right scheme built. With the land deal secure, LCR could proceed with the selection of a development partner for the King’s Cross site.

Selecting a Development Partner

It was agreed that LCR would bear the pre-development costs and lead on the selection of a development partner. In 1999, Jones Laing LaSalle was appointed to manage a two-stage open competition. In setting the terms of the competition, LCR deliberately did not ask for a masterplan or design. It considered the development problems to be economic, and political rather than architectural. It therefore sought a partner who could demonstrate a clear process and strategy for dealing with the complex planning and development process, and one with a participatory rather than an adversarial approach. LCR also wanted commitment to a long-term partnership whereby growth in value would be realised through the development of a ‘place’. The selection criteria were:

- Participatory approach and ability to work with Camden council and other stakeholders.

- The quality of the development team, and commitment from specific named individuals.

- The financial deal – not a sum, but an equation that maximised long-term values.

In seeking a joint venture, LCR did not require an up-front payment but instead offered an equity share. The landowner would provide the land and the developer would provide the cash on a 50:50 basis. This committed both parties into a process of maximising long-term values. The government also agreed to plough back the existing land value and take a return once planning permissions had been received.25

The approach ran counter to the standard procurement model that is weighted to achieving the highest financial offer.

The competition involved a wide trawl of potential firms, leading to an initial long list of 24. This was subsequently reduced to three, one of which was Argent.

Argent

Founded in the 1980s by Peter and Michael Freeman, Argent grew rapidly as a property investment and development company.

Argent’s major breakthrough came in 1993 with the acquisition of Brindleyplace, a 6.9 hectare site on the edge of Birmingham city centre, when its developer, Rosehaugh, went into receivership. Although it was still a relatively inexperienced company, Argent brought with it a fresh approach and understood the relationship between design, masterplanning and delivery in difficult and uncertain market conditions. It revised the masterplan to make the scheme more flexible; plot sizes were reduced to accommodate a variety of building sizes; circulation and access were reconfigured;

and a greater emphasis was placed on the public realm. Crucially, the revised plan was capable of being implemented in a variety of different phases according to prevailing market conditions. Argent then appointed respected architects to design individual buildings within an overall development framework.26 Brindleyplace was largely complete by 2001 and served as a useful reference point against which ideas for King’s Cross could be assessed.

In 1997 Argent was effectively bought by Hermes, the manager of the British Telecom pension fund. This gave Argent immediate access to £100 million of venture capital, as well as the larger resources of a £36 billion pension fund. The long-term investment perspective of a pension fund meant that high-quality design and astute estate management were valued as methods to maximise returns.

The Argent bid for King’s Cross

Initially the Argent board was not particularly interested in bidding for the King’s Cross development, but agreed that its chief executive, Roger Madelin, could submit a bid if he wished. Madelin was travelling to Birmingham on the 07.15 train from Euston when he turned his attention to the bidding documents and saw that the deadline for submission was 12.00 that day. He wrote a covering letter and submission on the train, mobilised the Birmingham office to type and fax it to London, where the background documentation was assembled. It was delivered to Jones Lang LaSalle’s offices with three minutes to spare. The submission was, by Madelin’s own words, ‘light’,27 but out of 24 initial bids it made the shortlist of three, alongside bids from Lend Lease and AMEC. At this point Argent mobilised. Recognising that the development would have a substantial residential component (where they had limited expertise), it entered a joint venture with St George, a subsidiary of the volume house builder Berkeley Homes, and formed a joint venture company, Argent St George. Both Roger Madelin and LCR’s Stephen Jordan have no doubt that without teaming up with a specialist house builder, Argent would not have won the bid. Argent and St George eventually parted company in November 2004 (see Chapter 9).28 The panel for the final interview comprised representatives from Exel and LCR.

While Lend Lease and AMEC presented detailed proposals and plans from internationally renowned architects, Argent St George’s pitch was different. Its proposition was that both the site and the political context were complex, and it would therefore be inappropriate to propose even initial ideas before a comprehensive analysis of the site conditions and constraints had been undertaken. Its experience from Brindleyplace underlined the need for flexibility to deliver a development that might run over a 20-year timeframe and at least three property cycles. Argent St George presented a single sheet of paper that set out a process. Central to this was sufficient time to have an extensive dialogue with local politicians and communities in order to achieve a proposal that would be robust and implementable. It was simple, brave and convincing; Argent St George was awarded the role of development partner.

Argent St George’s appointment

Initially, the decision to appoint Argent St George was not unanimous and split the panel. On paper at least, Lend Lease represented the lower risk option due to its size and experience. Four principle factors favoured Argent St George. First, the proposal was backed by an institutional investor (the British Telecom Pension Fund) and this guaranteed financial stability and continuity over the life of the project. Second, Argent’s development at Brindleyplace was gaining recognition as an exemplar and offered a convincing model for King’s Cross. Third, the panel was impressed by Madelin’s reputation and leadership credentials and sensed that it would be able to work with him. Finally, Argent’s stress on the importance of consensus building chimed with LCR’s own ways of working.

In establishing the joint venture, it was agreed that the land would be valued once the scheme had secured planning permission. The land owners had to deliver vacant possession of the site (see Chapter 9) and there was to be a calculation about how much value Argent St George would add through the planning process. The arrangement was that Argent St George would get an increasing discount on the price of purchasing their 50 per cent share of the development, incentivising optimal value through planning. In March 2000, the London Communications Agency (LCA), working on behalf of Argent St George, issued a press release to announce its appointment:

Conclusions

The first attempt to regenerate King’s Cross failed for a number of reasons. The construction of a new terminus for the CTRL under the Grade-I listed King’s Cross station was an expensive and risky engineering solution and although LRC had every right to believe that the government was fully supportive of its proposals, this was not cemented into an approved Act of Parliament.30 Without such assurances, the risks were very high. The LRC did appreciate the volatility of the London property market, but may have underestimated the difficulties in working with a Labour-controlled council compared to the more predictable environment in the City of London. The early 1990s economic downturn was unlucky, but no one ever accurately predicts such crises.

The final lessons from the scheme concerned the internal dynamics of the partnership. The LRC scheme was capable of being built, but British Rail was unable to focus sufficiently on property matters and seize the moment. The delay proved fatal; development is all about ‘timing, timing, timing’.31

The SOM and Foster masterplans were products of their time. Their approach to the listed buildings, demolishing some and preserving the rest as ‘artefacts’, now looks outdated. They did, however, act as a useful prototype against which subsequent plans could be compared.

Several factors prompted the negotiations to begin in earnest. First, the decision to terminate the railway at St Pancras removed uncertainty and risk from the development. It also resulted in the assembly of a site unencumbered by operational constraints, and in just two ownerships. The second factor was the government’s provision of direct investment in the interchange, and the financial arrangements that allowed private investment to be leveraged into the project. Third, the landowners agreed a pragmatic mechanism to value their landholdings. Personal relationships and the trust engendered were significant in setting a firm foundation for the scheme.

The decision to seek a development partner (Argent) who understood delivery, aspired towards high quality and was able to work collaboratively was a decisive factor. This might appear obvious but many procurement exercises, especially in the public sector, stress financial offer and risk minimisation as main criteria in decisions. Shared aspirations led to compatible working relationships and trust between landowners and partners. This relationship was to prove crucial in decision-making.

Several other points are important to the subsequent narrative and the success of the scheme and are worth re-emphasising. LCR’s insistence on taking responsibility for refurbishing St Pancras Chambers enabled a fully comprehensive project to take place. The refurbishment provided a dramatic and dignified entrance to the development and a clear statement that real change was at last happening at King’s Cross. It also established its credentials with English Heritage as a sensitive steward of historic buildings, and this helped to smooth later discussions on the future of the historic buildings on the railway lands. LCR also built strong networks with local stakeholders, and passed these on to its development partner. In consequence, Argent St George inherited a high degree of goodwill with the council and the local community, and this meant that subsequent negotiations started on a positive footing.