25. Motivation

Things need to be worth doing for themselves, not just for practice for some future time.

—JO WALTON, AMONG OTHERS

Playing games is a choice; it’s voluntary.1 Any game designer who is forcing people into playing games should seriously reconsider their craft. Given that, you must assume that people volunteer to play games because they want to. Thus, game designers must be intimately familiar with the motivations of players. What makes people want to play? What keeps people playing?

1 Caillois, R. (1961). Man, Play, and Games. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

An anthropological discussion of why humans play is beyond the scope of this lesson. For more on that topic, the definitive starting points are Roger Callois’s Man, Play, and Games and Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens.2 Instead, what I want to focus on here is the narrower concern of what motivates individuals to choose one thing over another.

2 Huizinga, J. (1967). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Two Types of Motivation

Many psychologists distinguish between two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic.3 The differences between these two types are important.

3 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Extrinsic motivation is best illustrated by the carrot and the stick. We are extrinsically motivated when we engage in a behavior for a reward distinct from the behavior. Many of us go to work for a paycheck, not simply to do the work. We exercise to look better or to be healthier, not simply because we enjoy the exertion. Sometimes we do homework just for the grade or because we know we have to in order to get the career we desire. In all these cases, we engage in a behavior for some reason other than the behavior itself.

Intrinsic motivation is when we engage in a behavior simply because we gain fulfillment from that behavior. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who popularized the concept of flow, explains intrinsic motivations as autotelic. Autotelic comes from Greek and literally means “self-goal.”4 The goal of doing the activity is doing the activity. We play games because we like to play games. We read books because we like the experience. We listen to music because it’s enjoyable. In all these cases, the ends are the means. The motivation is intrinsic to the activity.

4 Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

What’s the Problem with Rewards?

Gamification is a popular current trend that can largely be boiled down to putting external motivators such as points, badges, and achievements onto behaviors to encourage people to engage in them. There are gamified programs to read books, work out, even to learn. The idea is that by pairing an activity with a reward, the “players” are motivated to do that activity in the hopes of receiving the reward. Gamification is nothing new; frequent flier miles, “high roller” programs, and even the concept of grades in school are all ways to gamify behavior that were designed well before the term was coined. These external motivators were tested by Skinner and the behaviorists. The rats that push the lever are not pushing the lever as an autotelic activity. They push because they want the food. The push is contingent on the expectation of receiving the food.

In games, the primary goal is generally for the player to have fun. The designer hopes that the player does that through interacting with the game’s systems in a particular way. Some designers choose to add external motivators to guide player behavior—for instance, receiving an achievement for finishing the tutorial or a special character for using all the attacks. At the same time, though, the designer wants the player to be intrinsically motivated in the game itself. What good is the game if it is not fun or rewarding in itself? What could be wrong with that approach?

In 1973, long before gamification was a popular buzzword, Mark Lepper and his colleagues conducted an experiment to find out how external motivators affected internal motivators.5 They divided some 4- and 5-year-old school students into different classrooms. One classroom was the “expected reward” group. That group was told that if they chose to draw during playtime, they could receive a Good Player Award—a little certificate with their name on it. The students who chose to draw were then given the certificate. A second classroom was the “unexpected reward group.” Those students were not told in advance about the reward, but the students who drew during playtime were given the Good Player Award. A third classroom was a control group. They were free to draw or not as they pleased but received no award regardless of what activity they chose. One to two weeks later, the researchers returned and noticed over the next few days how much of the children’s free time was devoted to drawing.

5 Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973). “Undermining Children’s Intrinsic Interest with Extrinsic Reward: A Test of the ‘Overjustification’ Hypothesis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 129.

The students who received no award regardless of what they did spent 16.7 percent of their free time drawing. The students in the unexpected reward group, those who chose to draw and then were surprised with an award, spent 18 percent of their time drawing, a small boost over the control group. However, the students who were given the expectation of an award spent only 8.6 percent of their free time drawing. It turned out that unless they were being rewarded for it, they no longer wanted to draw!

Similar experiments have been repeated many times, with similar findings. One of the most popular external motivation programs in American schools has been the “Book It!” program. Sponsored by the fast food pizza chain Pizza Hut, the program rewards students for reading by giving them pizzas. However, the program has been criticized because children often read small books and fly through them without being able to answer basic questions about the book that would prove their comprehension. The students just want the point so they can get the pizza. It even decreased the amount of reading students did outside school.6

6 Kohn, A. (1999). Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Self-Determination Theory and Challenges

So what do people want? Of course, this is a massive question with a wide variety of discourse. One of the most well-respected and well-tested theories is Deci and Ryan’s work on self-determination theory. Self-determination theory says that there are three needs that humans strive for across time and cultures, and it is these three elements that help explain what makes us intrinsically motivated, assuming that our basic needs, like food and shelter, are satisfied.

The first need is autonomy. People need to feel control in some measure of who they are and what they do. The second need is mastery. People need to feel as though their actions control their life’s outcomes. Last is relatedness. People have a need to connect with others in some way. Naturally, some needs are more important than others for different individuals.

Games are clearly in the practice of tasking players with activities that challenge their mastery and autonomy. It’s part of why games are so widespread in most cultures.

Stimulating the quest for mastery is something that games can do easily. However, when coupled with contingent rewards (as in the Good Player Award example), the reward serves to dampen the desire for mastery and hence the motivation to continue with the behavior. It’s not the reward that is the problem; it’s the expectation of the reward that is the problem. When a person expects a reward, then their motivation shifts to doing the task for the reward. Their inherent need for mastery is no longer served by the task, and so they become uninterested in it when the reward is no longer present. It’s why educational psychologist John Nicholls said that the likely result of the aforementioned Book It! program would be “a lot of fat kids who don’t like to read.”7 The motivation for reading had become pizza instead of the mastery and autonomy previously associated with reading.

7 Kohn, A. (1995). “Newt Gingrich’s Reading Plan.” Alphie Kohn. Retrieved July 7, 2019, from https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/newt-gingrichs-reading-plan/.

If you want people to keep playing, then you need to stimulate their desire for mastery. However, it’s important to note that games do not need to keep the player playing forever. Portal is just as valuable a game as Dark Souls even though the former caps mastery around a shorter experience. The designers of Portal simply do not care if the player plays for three hours or 60.

Remember also the justification for mastery. People need to feel as though their actions control their life’s outcomes. If something is too challenging or not challenging enough, then they will not feel that their desire for mastery is being satisfied. Dark Souls is certainly not a game for everyone. It’s simply too brutally hard for many. However, for those who are able to progress in the game, it provides a valuable mastery activity. The game has to be challenging, but not so challenging that the player feels he cannot overcome it. This clearly parallels the fundamental game design directive discussed in Chapter 9.

Competition and Motivation

One of the play aesthetics that comes easiest in game design is competition. Games pit one player against another or one player against an algorithm and assume that the player’s inherent desire to win will be enough to be motivating. Sometimes this is true. Sometimes it’s not.

Because of competition’s origins as a male-dominated pastime, the hobby is seen as a standard play aesthetic. However, although competition is a common motivator for men, women (especially when paired with men in the same competitive space) often show decreased motivation and performance in competitive environments.8

8 Gneezy, U., Niederle, M., & Rustichini, A. (2003). “Performance in Competitive Environments: Gender Differences.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. Cambridge Massachusetts, 118(3), 1049–1074.

Another interesting finding is what psychologists call the N-effect. The N-effect is that competitive motivation decreases when the number of competitors increases. To find this out, researchers had students complete a quiz as quickly as possible and told them that the top 20 percent would receive a cash prize.9 One group was told they were competing against 10 other students; another group was told that they were competing against 100 other students. The group who was told they were competing against 10 students finished their quizzes much faster than those who thought they were competing against 100. The ones who thought they were competing against 100 others were less motivated. They thought they could not possibly win against so many competitors, even though their odds of winning were the same.

9 Garcia, S. M., & Tor, A. (2009). “The N-Effect: More Competitors, Less Competition.” Psychological Science, 20(7), 871–877.

Very few games integrate this lesson. One that does, however, is SpaceChem, a clever but complicated puzzle game whose puzzles often have multiple solutions. Instead of using a global leaderboard to show the player with the best solutions (as most games would do), the game instead shows where the player ranks as a percentage using histograms (Figure 25.1).10

10 Barth, Z. (2012, June 6). “Postmortem: Zachtronics Industries’ SpaceChem.” Retrieved July 7, 2019, from www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/172250/postmortem_zachtronics_.php?page=2.

SPACECHEM IS © 2011 ZACHTRONICS. IMAGE USED WITH PERMISSION.

Figure 25.1 Histogram-based leaderboards in SpaceChem.

This serves to reduce the intimidation of the N-effect. You no longer know you are competing against thousands of others; instead, you know how you compare against the average. As SpaceChem’s designer says, “For most players, the only thing a global leaderboard manages to tell you is that you suck (and not even by how much).”

Another example is in the free-to-play card game WWE SuperCard. One of the features allows the player to play a season’s worth of games against other players for in-game rewards. Many games choose to give the top 100 players in the world every week some reward. What WWE SuperCard does instead is limit your competition to 15 other randomly chosen players at around the same power level. This serves to make the challenge of beating players seem manageable and serves to support motivation.

Personality

One of the most difficult aspects of game design is that most often, designers must design for people with different wants, needs, emotions, and mental processes. Psychologists call this collection of traits personality. Personality affects so many of the choices we make—both within games and toward which games we are drawn.

Although many psychological concepts are subject to intense debate within the scientific community, the most popular model of personality factors is both widely accepted by the scientific community and verified by many different types of research. This model of personality is known as the big five personality traits, and it is often referred to by the acronym OCEAN. These traits are independent of each other and together they form a complete summary of a person’s personality.

This is covered more completely in Chapter 14.

Other Motivation Effects

There are a few other results from the study of motivation that have particular applicability to games.

The goal-gradient effect appears in nearly every game with a level-up bar. The goal-gradient effect says that players are more motivated to reach a goal the closer they are to that goal. Think back to the discussion of behaviorist schedules of reinforcement from Chapter 23—a player interacts furiously with a system as he gets closer to the time when he knows the reward is about to appear in fixed schedules.

In games, designers leverage this by showing players a visual representation of how close they are to the next level or objective (Figure 25.2). When the player knows that she is almost at a reward, it keeps her motivated to continue the behavior that will lead to that reward.

FARMVILLE 2 IS A TRADEMARK OF ZYNGA, INC. AND IS USED WITH ITS PERMISSION. © 2015 ZYNGA INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 25.2 A bar to fill in FarmVille 2.

In many games, players are rewarded with additional XP on big events that cause a level-up to occur and partially fill the next level’s XP bar. This gives the player a somewhat illusory sense of progress toward the next level and motivates her to continue the game. This is much like the Kivetz (2006) study from Chapter 23, in which customers got free stamps on a dining loyalty card and were motivated more than were customers who needed the same number of stamps to reach a reward.11

11 Kivetz, R., Urminsky, O., & Zheng, Y. (2006). “The Goal-Gradient Hypothesis Resurrected: Purchase Acceleration, Illusionary Goal Progress, and Customer Retention.” Journal of Marketing Research, 43(1), 39–58.

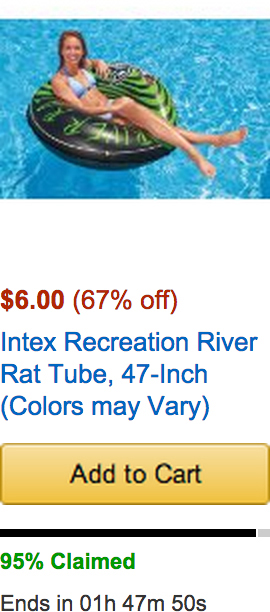

Another motivation technique common in games is the concept of scarcity. It is seen often outside of games in the context of sales. Look at the Amazon image in Figure 25.3.

AMAZON

Figure 25.3 Best hurry.

Not only does Amazon limit the sale by time (only 1 hour and 47 minutes remaining!), but they also limit it by quantity (95 percent of these pool toys are gone! I have to act now!). Scarcity is highly motivating. In one famous experiment, subjects were asked to test cookies from two different jars.12 One jar had many cookies in it; the other just a few. The subjects reported that the cookies from the jar with fewer cookies were more delicious, even though both jars contained the same brand of cookie. Scarcity makes us value things more and motivates us to acquire them.

12 Worchel, S., Lee, J., & Adewole, A. (1975). “Effects of Supply and Demand on Ratings of Object Value.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(5), 906.

Croteam’s The Talos Principle shows the concept of scarcity in action. By using a found axe, the player can travel to a secret area in each section, use the axe, solve a number of tangram puzzles, and unlock the single-time use of a helper robot to give the player a hint on a puzzle. Only three of these helper robots are in the game, and once one is used it’s gone forever. It feels good to unlock that scarce resource, so you spend the time to do it. This is despite the fact that it would take less than a minute to YouTube an answer to each puzzle instead of going through the effort to unlock a hint.

Summary

• There are two kinds of motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic. Intrinsic motivation is the motivation to do something as its own end.

• Extrinsic rewards can dampen the intrinsic motivation for a task.

• The three desires in self-determination theory that help predict human motivation are autonomy, mastery, and relatedness.

• The goal-gradient effect suggests that as players get closer to a goal, they will be more motivated to achieve that goal. Reminding players how close they are can reinforce motivation.

• Scarcity is inherently motivating. Players will value items more if they believe there are in limited supply.