Scriptwriting

Portable video projects come in all sizes and shapes. They can be long or short, dramatic or comic, fictional or factual. Whatever form they take, they all begin with a script. Scripts are necessary for electronic news gathering (ENG) and electronic field production (EFP) because they are blueprints or diagrams of the way stories are put together.

Regardless of style, intent, or format, video scripts have something in common: They are all written for the spoken word (the ear) and for the visual message (the eye). Writing for video (writing to be seen and heard) is unlike writing for the print media (writing to be read). Readers of the print media can read at their own comfortable pace. They can reread words or sentences whenever necessary. This puts the burden of comprehension on the reader.

In video, the script must be written in such a way that it is comprehensible to the audience the first time it is viewed and heard (unless it is a training video that can be replayed). All viewers see and hear the video at the same rate. Even if viewers watch a program by themselves and are able to replay it, video scripts should be understandable at the outset.

Writing for any script requires both commonsense and talent. A writer needs commonsense to realize that writing for the ear requires relatively short sentences, words, and phrases that are easy to pronounce and unambiguous in their meaning, and a conversational style. Writers demonstrate their talent by conveying precise meaning and selecting creative and interesting approaches to the material. This is not always easy—many scripts deal with mundane factual material, such as a piece explaining how a mowing device is connected to a tractor. A talented scriptwriter can take dull, factual material and present it in an interesting way.

ELECTRONIC NEWS GATHERING

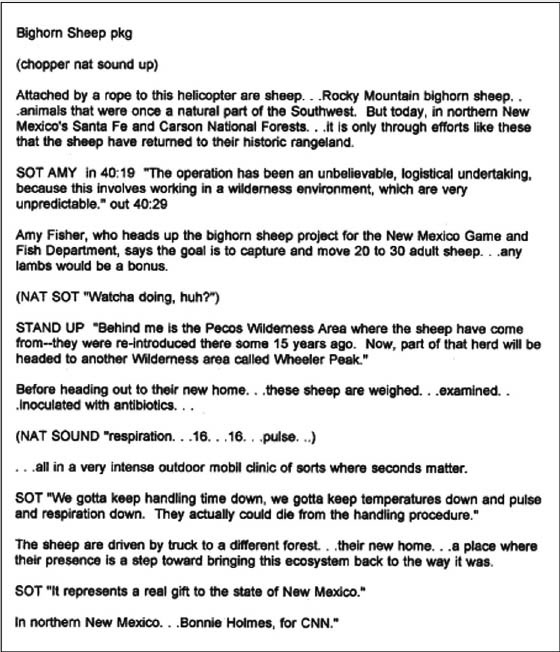

Scripts for ENG stories are generally written by the news reporters who cover the events for those stories. These journalists are often trained in broadcast journalism and have certain conventions they have learned to follow. Hard news stories, such as major fires, crimes, or elections, require quick turnaround time—the story is often written the day it is broadcast or even just minutes before it airs. Soft news features, stories that do not necessarily involve hard news and are not time sensitive, are more like EFP projects, because they can allow for more planning time and need not be aired the day they are shot. They have a longer “shelf life” than hard news stories. (See Figure 5.1.)

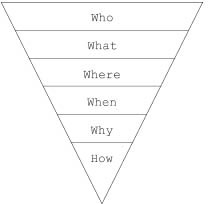

W5H and the Inverted Pyramid

Whether hard news stories or soft news features, ENG projects are written to convey precise and understandable material in an informative yet interesting way. The written material should address the well-known “five Ws and an H” questions (W5H) that all journalists are trained to answer: who, what, where, when, why, and how? These questions are often diagrammed as an inverted period, with the most important information at the top, or front, of the story and the more detailed, fill-in information at the bottom, or end. (See Figure 5.2.) In this way, if the story has to be cut short to clear airtime for another, breaking story, the end can be cut off without losing the critical information at the start.

FIGURE 5.1

This script for a news feature includes natural sound on tape (SOT), footage of sheep being handled and transported, and a reporter’s stand-up shot. (Courtesy of Bonnie Holmes)

While the inverted pyramid is a useful tool that all journalists learn, some choose to arrange the information differently, developing a unique style. A common example is starting a script with a “hook” that might be, say, a “how” question, followed by the basics of who, what, when, and where. A story about a chef, for instance, might begin, “Butter … that’s how Chef Ima Cook keeps her customers coming back. It’s her secret ingredient.” After that opening, the story could then reveal where she cooks, what her best dishes are, and so on. As with any other craft, it is wise to learn the basics of the W5H and inverted pyramid first and apply them to perfection. Then, once you know how to change the basics with purpose, you can develop your own “voice.”

FIGURE 5.2

The inverted pyramid of journalistic questions.

Writing to the Visuals

The biggest difference between ENG and EFP scriptwriting is that ENG scripts are almost always written after the video has been shot. After an event has been covered, the reporter reviews the footage and writes a script so that the raw shots can be edited into a finished story. This process is sometimes called writing to the visuals. This includes scripting a brief explanation for the reporter to say in cases where the video is missing some element, but also not overscripting—writing too much when the visuals convey the story. This procedure of scripting after the shoot is necessary because the reporter is often unsure of what is going to happen at the event or what the usable footage will be until after the recording has been made. Keep in mind that a reshoot or second take of an event is often impossible in ENG.

The ENG script is written between the time the event is shot and the time it is broadcast. The word “broadcast” here refers to all possible means of distributing, or “casting,” the story to an audience, including over-the-air, cable, satellite, Internet, podcasting, and the like. For traditional television broadcasting, this usually means writing the script during the afternoon just before the evening newscast. The ENG writer has maybe an hour or sometimes just minutes to write the script. This is quite different from scriptwriting for EFP.

Writing Interviews

Not all ENG writing occurs after the shoot, however. In the case of interviews, reporters need to script their questions in advance. To be sure, they need to be flexible and adapt to each situation. After starting with the scripted questions, they might discover a more interesting angle during the shoot, in which case veteran reporters know to follow a line of new questions that explores that angle. However, that new angle is only discovered in response to carefully thought-out questions in advance. With well-scripted questions going in, the reporter is ready to follow the script or to adapt and follow a new angle if one presents itself.

You do not want to write close-ended questions, those that can be answered by simple “Yes,” “No,” or “I don’t know” responses. These don’t give you anything to use in editing the piece. For example, consider a feature about the local dog catcher. A close-ended question, such as “Do you like your job?,” does not require the dog catcher to speak much. Instead, you want to write open-ended questions, those that elicit sentences that can be used as soundbites in the video. An open-ended prompt, such as, “Tell me about your favorite part of this job,” is more likely to result in useful soundbites, perhaps the dog catcher enthusiastically relating a story about reuniting a lost pet with its owner. Some writers prefer two-pronged questions in which a short, factual answer is followed by a longer, expository response. An example of a two-pronged question is, “How many years have you worked here and what is the most unusual thing you have seen in that time?” This might elicit a nice and usable response such as, “In the 15 years I have worked here, the most unusual thing I ever saw was….”

Writing Style

Many books cover in detail the writing style for broadcast and electronic news. This text cannot cover every consideration, but the most foundational considerations are presented here. Use these guidelines when you write scripts for ENG. Keep them in mind for EFP writing as well, because they are generally good points for most kinds of writing.

Primacy and Recency The theory of primacy states that we tend to remember first things—images and sounds that we first encounter before others. The theory of recency argues that we also tend to remember most recent things—images and sounds that are freshest in our memories. These two theories argue for the importance of a strong open and close in a news script. Begin with a powerful image and soundbite to tease the viewers into the story. The middle should then be brief and should show and tell the main points in pictures and sound. The close, being the most recent in the viewers’ minds after the story ends, should go out with a bang: another powerful image and soundbite that give the story closure.

Present Tense, When Possible Be cautious using “today” and “yesterday,” because these words are often unnecessary and are implied in each day’s news stories. For the immediate past, such as a police rescue in the last few hours, you can use the present (e.g., “Police rescue …”). For the longer past, such as Abe Lincoln’s death, you should use the past tense, but because you’re writing for a present audience, look for ways to give your writing a present “spin” (e.g., “A new discovery about Abe Lincoln, who was assassinated in 1865, reveals that …”).

Action Words Write action rather than description. Television uses both pictures and sound, so always think of aural and visual imagery in your scripts. For example, write, “President Obama points his finger to the right,” rather than, “President Obama is angry at conservatives.”

Active Voice Write in the active rather than passive voice. For example, write, “She hits him,” rather than, “He is hit by her.” As with all these guidelines, use common sense. For example, if the person being acted upon is the key to the story, say a celebrity, then you can consider an exception and use the passive (e.g., “Jane Movie Star is struck by a stalker”).

Conversational News writing is to be spoken, not read, so write for the ear. For example, write, “Unlock the door,” rather than, “Part A, insert key; part B, turn key; part C, push or pull door until open.”

Individual Viewer Write for the individual at home watching your story. The audience might be mass, but people tend to consume electronic media alone or in small groups of friends or family. Pretend you’re there in the room. For example, write, “Hurricane Xena is heading up the coast. Here are some precautions you might want to take.” Do not write, “Ladies and gentlemen, it is my duty to inform you that a hurricane is approaching. Do not panic. Repeat: Do not panic. Listen carefully to the following instructions.”

Short Statements Write short, simple, declarative sentences, rather than rambling, run-on sentences. Shorter sentences are easier to read and less confusing. For example, write, “Dick runs. Jane runs. Spot chases Dick and Jane.” This is clearer than writing, “As Dick continues running down the street, Jane pursues him at a relatively rapid pace, while Spot, the dog, runs close behind, ever gaining ground.”

Brevity Broadcast time is money. Waste no words. Write directly to the point. Always consider ways to cut words out of your sentences without losing meaning. Be as concise as you can with no extra words. For example, write, “He falls down,” rather than, “He then proceeds to fall down to the ground.” The phrase “then proceeds to” is unnecessary, and “to the ground” is assumed in the phrase “falls down.” Do you see how three words in the first sentence convey the same meaning as nine words in the second sentence?

Avoid Unnecessary Words People tend to load their talk with lots of unnecessary words. While news writing is conversational, it is also economical and should not waste time with these meaningless and often cliché additions to sentences. Some words to avoid: actually, basically, respectively, latter, former, that. For example, write, “He announces his resignation,” rather than, “He basically announces that he is going to resign.”

Avoid Redundancy In keeping with the guideline to be brief, avoid words that repeat something already in the sentence or something that can be assumed. For example, consider this sentence: “Right now, firefighters are presently battling a blaze.” The phrase “right now” and the word “presently” mean the same thing, so one or the other (or both) should be deleted. Another example: “The project is designed to inform community leaders about the objectives of the project.” The word “project” is repeated, so different wording should be used to conclude the sentence.

Source Attribution Print news places the source of information at the end of a sentence; for example, “The president’s health is excellent, according to White House officials.” In contrast, broadcast news places the source at the beginning of a sentence; for example, “White House officials report the president’s health is excellent.”

KISMIF You already know this one, and it applies to ENG writing as well as to EFP writing: Keep it simple, make it fun.

ELECTRONIC FIELD PRODUCTION

Generally, EFP scriptwriters have much more time for the process than scriptwriters in ENG. EFP scripts are often written with enough lead time to allow for careful review and revision. The process allows a script to be evaluated not just for its meaning and effectiveness, but also for its adherence to the budget and capabilities of the production unit.

Scripts for commercials, training videos, entertainment, and so on can be written and rewritten until the scriptwriter, producer, director, and client are satisfied. The scripts usually do not have to reflect the reality of an event or issue as they do in ENG, but they must reflect the concept and intentions of the client and/or producer.

The procedure for EFP scriptwriting is often careful and lengthy:

1. Set goals for the script.

2. Analyze the target audience.

3. Select a format and style.

4. Develop a central visual theme.

5. Research to learn about the concepts to be shown and explained.

6. Write a treatment that conveys the essence of the script.

7. Prepare an outline that lists, in order, all the important aspects of the script.

8. Write the script.

9. Review and revise until all those involved are satisfied.

10. Develop a storyboard to help others visualize your ideas.

11. Develop an editing script in postproduction, making note of any changes in editing that were not part of the shooting script.

12. Throughout the process, pay attention to the basic story structure: beginning, middle, end.

Throughout these 12 steps, you must also keep in mind the budget for the project. You cannot write a script that will require more money to produce than has been allotted. For example, if the script is a commercial with the goal of selling fishing boats, and the manufacturer has budgeted only $1,000, that epic pirate battle you envision will have to give way to small dueling watercraft, provided by the manufacturer, with employees as actors, shot on the local river. Budgets are covered extensively in Chapter 11.

Goals

Once the process of initiating a video project has begun, set your goals at a reasonable and attainable level. Attempting to present the entire history of a large corporation in a comprehensive and detailed fashion might be unrealistic in a 3-minute portion of a 10-minute video presented to stockholders at their annual meeting. It might also destroy your budget. The best way to avoid a problem like this is to set specific goals. Goal outlining should be done on two levels. First, determine the overall purpose of your project. Is it to entertain, inform, educate, demonstrate, or persuade? Then set very specific goals.

An instructional video that attempts to familiarize the sales managers of a farm-implement company with a new model tractor might have the following goals:

• Inform sales managers about the new model: size, weight, performance, and cost.

• Motivate them to sell the new model by explaining bonuses and incentives.

• Train them in marketing and sales procedures that will enhance sales of the new model.

Goals should be formulated in terms of their intended outcomes, or effects, on the viewers. Any communication may have three different kinds of effects on an audience: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. Cognitive effects are those that occur when the audience gains knowledge or information. These effects impact what viewers think or know. Emotional effects are those that cause an attitudinal or mode change in the audience. These effects impact the way viewers feel. Behavioral effects occur when viewers engage in or change actions in some measurable way, such as buying a new brand of detergent or voting for a certain politician. These effects impact what viewers do. In the planning stage, these potential effects can be viewed as obtainable goals or objectives.

Many video projects do not have all three types of desired objectives. Educational videos might be designed only to achieve cognitive effects. Artistic or entertainment videos might only strive for emotional effects. Simulation videos might attempt to teach the audience how to behave in certain situations. Of course, some videos might have goals that impact the audience in all three ways. It is appropriate to consider all three types of effects for your intended audience.

Target Audience

Once you have established the goals for your video, it is time to pay more serious attention to your audience. Your production can be tremendously exciting, visually creative, and perfectly shot, but it might be a total failure if your script is not written for the intended viewers. Consider the difference in a script for a feature that will appear on a local broadcast station’s magazine show and a script for a video that will be shown only to volunteers for a charity at their organizational meeting. The topic might be the same, but the style would be quite different.

The magazine show feature is scripted to heighten awareness about the good things the charity does and the need for volunteers or donors to help. The video shown at the organizational meeting would be written to raise the enthusiasm and energy level of the audience and demonstrate or suggest specific behaviors needed to help the charity. This same charity might want to produce a video for use in elementary schools to inform children about the importance of the charity’s efforts. Obviously, the language of the script and the pacing and style of the shooting and editing for children would be different from either the magazine feature or the video made for committed volunteers.

The more you know about your audience, the better. Demographic factors are perhaps the best starting points to help you become familiar with the audience. Demographic characteristics are quantitative: They are objective and measurable. Typical demographic categories include age, gender, ethnicity, income, and education level. What is the age range of your viewers? Does your script target males more than females, or vice versa? Is the video intended more for one ethnic group than another? What is the income range of your audience? How much education do the members of your intended audience typically have?

You should also consider psychographic factors. These are qualitative: They are subjective and more descriptive than measurable. Typical psychographic categories include lifestyles, values, attitudes, interests, and hobbies. How does your target audience live? What do your intended viewers consider important in life? What are their impressions of your subject likely to be? What captivates their imaginations? What activities do they pursue? Information about both demographic and psychographic factors will help you make some basic decisions about your script. Writing for a small, well-defined audience can be very different from writing for a large, heterogeneous audience.

The exhibition of the final product is also a consideration. Will 10 people see the video? 10,000? 100,000? How will the video actually be shown? On broadcast TV? Cable or satellite? A podcast? Streaming media? A private DVD screening to a small audience using a small TV monitor? A showing to an audience of 100 or more using a large projection TV? Will a frame or even the entire video be part of a World Wide Web page, Internet site, or multimedia presentation? After you have carefully considered the audience and how that audience will watch your project, you can move on to deciding your format.

Format and Style

Video projects can be categorized by their format, which refers to the overall organization and intent of the project. Broadcast TV programs conform to a limited number of standard formats that provide understanding of the type of entertainment and a timeframe for viewers. In broadcast, most programs are written for 30- or 60-minute lengths. The most common formats include:

• Drama

• Newscast

• Game show

• Event (e.g., sports, awards)

• Compilation/video clips

• Action/adventure

• Variety show

• Situation comedy

• Talk show/interview

• Documentary

• Highlight (e.g., sports, awards)

• Magazine/features

• Reality program

• Tabloid entertainment news

Many of these formats have been adapted to nonbroadcast situations to get attention and to increase viewer appreciation. For example, a new health benefit could be explained to employees of a large corporation by an executive talking to the camera and using an occasional chart or graphic. Another approach might have employees in a simulated game show, like Jeopardy, trying to give answers to questions about changes from old benefits to new. The parody of the game show format gives the writers the opportunity to inject humor into what might be very dull material. Another approach might be to have a TV talk show host interview the company executive, rather than having the executive do a talking head. The show becomes more visually interesting, and the question-and-answer format allows the host to represent the viewers and their anticipated questions.

Other formats are more appropriate for nonbroadcast TV projects or those that are not fixed program-length. These include:

• Demonstration/how-to

• Instruction/classroom topics

• Public service announcement (PSA)

• Music video

• Video art

• Commercial

Choosing one of these formats or a combination can give your project structure and organization that will be helpful to you as a writer and to your audience as viewers.

The style of your writing can vary considerably, but in the context of ENG and EFP we can categorize styles of writing by how the information of your text gets into your program. You can have an announcer give information, usually referred to as narration. You can have dialogue—words delivered by two people at a time—that is either informational, dramatic, comic, or simply entertaining. You can have a combination of either of these with natural soundbites—words delivered by an interviewee in response to prompting or a question.

NARRATION

Narration is usually a simple, straightforward reading of the script by a narrator or announcer. The narrator is usually not on camera, nor recorded when the video is shot. Narration is also referred to as voice-over (VO). It is common practice to record the narration at a recording session separate from all visual shooting.

Narration should be written to enhance the video and make it more compelling. Good narration guides viewers to a specific time and place that is represented by the video. This can be important when your setting is somewhat generic. For example, an opening shot might be a person in bed sleeping in a darkened room; an alarm clock next to the bed reads 3:10. The audience automatically assumes the setting is at night. Because the intention of the video is to inform the audience about the dangers of sleep deprivation and irregular sleep behavior, the narration could tell the audience that it is 3:10 PM, not 3:10 AM. The opening narrative line could be:

If it were 3:10 AM, Ralph Salesman would not be shown in this video. The problem is that this video was shot at 3:10 PM, when Ralph should be meeting with sales clients. Ralph suffers from “nonsleepnia,” a condition that is characterized by irregular sleep patterns. In this video we will discuss this vexing behavioral problem and suggest proper methods of treating it.

The narration helps establish the scene and leads the audience into the purpose of the video. In other words, the narration can be a necessary part of the establishing visual shot.

Narration is best when it is succinct and used sparingly. Don’t use it unless it adds something to the video. Heavy narration might be necessary for a training video or a video dealing with events that occurred but were not shot (e.g., some historical event before the age of photography), but in all cases, avoid continuous, monotonous narration. Organize your narration in complete thoughts, like paragraphs in the print media. Don’t be afraid to break up your narration with periods of silence (assuming you have good video) or to change your narrator or use soundbite-type material when appropriate people answer questions relevant to the topic of your video.

Because video projects are written for the ear, the style of narration should be conversational, not overly flowery or stiffly formal. Remember, your video might be viewed by many people at once, but videos are most effective when they reach people as individuals, similar to interpersonal communication. Write for one person, even though your video might be seen by thousands.

DIALOGUE

Dialogue is commonly used for dramatic presentations or when situations are dramatized. To write dialogue, you have to write in more than one voice. Some writers find it best to work with a writing partner so that each can assume a different voice. They then create the dialogue by improvising back-and-forth banter. Although referred to as dialogue, this style of writing obviously also encompasses more than just two people. Most writers strive to achieve economy in their dialogue, writing conversationally but not wastefully. In this way, they create just the dialogue needed to move the story and reveal characters without wasting words and time.

INTERVIEW

Many informational programs have a combination of narration and dialogue. The dialogue sometimes consists of responses from persons who are interviewed for the program. For example, a video designed to explore a company’s role in preserving the ecological integrity around one of its manufacturing plants could open with narration extolling the virtues of the company’s efforts at preservation. It could then include soundbites from credible authorities, such as biologists, who respond to questions about the environmental conditions at the site. When using interviews, keep in mind the guidelines about open-ended questions discussed previously under ENG. The questions should elicit usable soundbites for editing.

Central Visual Theme

Your central visual theme should be stated as a short phrase or sentence that conveys the essence of your visual goal. It summarizes the look of your project. The statement should include the major visual elements of your story.

For example, if the project is a 30-second public service announcement for the local public library, an appropriate phrase might be, “Books are your windows to the world.” An appropriate phrase for a 5-minute demonstration video of a new computer workstation could be, “The new Plum III computer fits your desk, your hands, and your mind.” A training video for employees of a bakery might have its visual statement, “Dough is our bread and butter.”

By stating your visual idea in a short, succinct, central, visual theme at the beginning, you prevent further levels of script and production complexities from obscuring your original intent. Should problems arise during the preproduction phase of your project, it may be helpful to review your initial statement. That statement provides you with an overall visual theme to tie together the shots in your project. As you write the script, you can find creative ways to include this visual theme throughout.

Research

Because producers of EFP videos provide their services to many different kinds of clients, EFP projects often require familiarity with technical terms or procedures beyond the realm of the producer’s experience. A complete video project requires fluency in both the video and audio portions of the project, and research is often necessary to attain this fluency. This fluency can be achieved in four ways:

• Interviews with knowledgeable individuals

• Reading material relevant to the topic

• Viewing other information previously prepared either by or for the client

• Searching for information available on the Internet

INTERVIEWS

Interviews with experts may serve two purposes. By discussing the video topic with a person in-the-know, you will understand the topic better and can write a coherent script that uses appropriate terminology correctly. Additionally, you may be able to record the interview, providing potential source footage for your project, with the permission of the subject, of course.

READING MATERIAL

You should gather as much relevant reading material as you can. You can ask the experts whom you interview for recommendations of items to read. You can also search for books, trade journals, newspaper and magazine articles, newsletters, web sites, or other sources that explain the topic and provide background information. Books might also be available to give in-depth information for longer projects or for those involving highly technical subject matter.

CLIENT INFORMATION

Information that originated from the client is potentially the most helpful, but it is often overlooked. Press releases, marketing information, advertising, sales brochures, or previous video and audio projects can give a quick and accurate overview of the client’s goals, techniques, or philosophy.

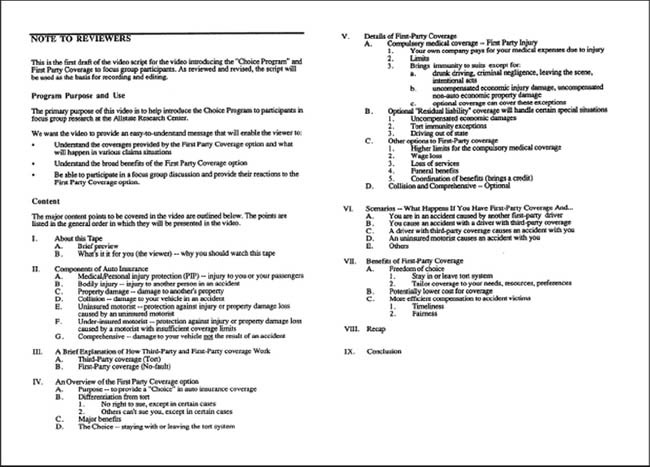

FIGURE 5.3

A screenshot from the popular search engine, Google. (Courtesy of Google)

For example, some years ago, a sugar manufacturing company needed a video that would give a brief history of the company and describe the steps taken to manufacture sugar from sugar beets. The DVD was to be produced for elementary schools and libraries. After checking numerous possible sources, it was found that an old brochure gave much of the historical information and a 20-year-old film had animation sequences in it that helped show and explain the complex technical processes involved. In fact, the animation sequences were still accurate enough that some careful editing allowed them to be transferred to video and used to explain that portion of the company’s operation. Needless to say, much time and money was saved as a result of the research for related materials.

INTERNET SEARCH

Just about any topic, person, or place can be researched through the resources available on the Internet. If you have a good idea regarding what you want in your search, many of the search engines available can find very specific information for you in a very short time. (See Figure 5.3.) Just about anything, including photographs, diagrams, audio, and video, can be accessed and even downloaded to help give you a better understanding of your topic.

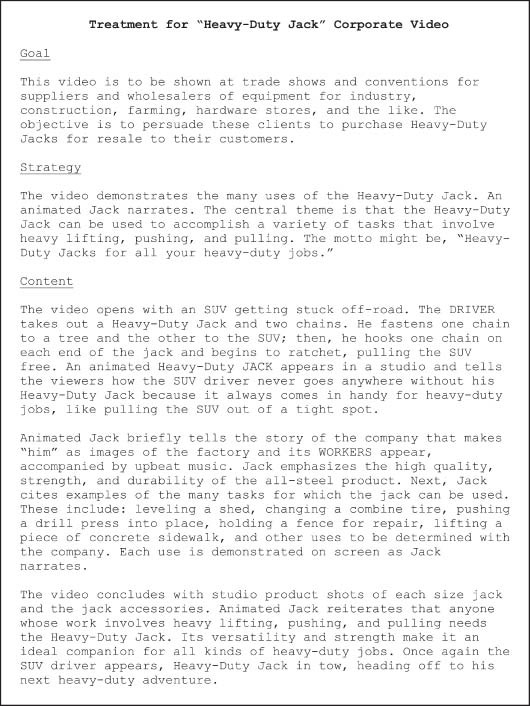

Treatment

Presentations involving drama, characters, and a plot require a stated treatment or brief summary of the project, written in the earliest stages of preproduction to allow the creator (or scriptwriter) to tell the story and better orient the production team, as well as the scriptwriter. The treatment is a short encapsulation of the setting, characters, points of view, and the plot. Major events or changes in characters or characterizations should be mentioned in the treatment. While this step is required in fiction, it is also strongly recommended for nonfiction. The treatment tells the story in narrative form (without dialogue) so that the client or financial backers have a good feeling for what the finished product will look like.

The treatment not only keeps the scriptwriter on track, but it also keeps other members of the creative team and the client on track. The treatment provides firm guidelines for everyone to remember throughout the creative process. For informational projects that have a nonfiction style, the treatment might be quite brief—one to three pages for a short video. This type of treatment should contain three elements: goal, strategy, and content. (See Figure 5.4.)

GOAL

The goal of the project should accurately reflect what the originator wants: training, promotion, publicity, or whatever. The goal statement should also include the target viewers to whom this goal is directed. This should be accomplished in a few sentences or a single paragraph.

STRATEGY

The strategy of the production explains what method will be used to accomplish the goal. If the goal is to teach salespeople how to use a new laptop computer to enter sales data, the strategy might be a step-by-step demonstration showing the computer and the data-entry procedure. If the goal is to heighten awareness of a new health benefit, the strategy might be a simulated press conference with the most commonly expressed questions asked and answered. If the goal is to increase sensitivity toward minority groups in the workplace, the strategy might be a series of brief scenarios depicting potential problem situations and how to react to them.

FIGURE 5.4

This sample treatment for a sales video for a heavy-duty jack summarizes the goal (including target audience), strategy (including central theme), and content (including beginning, middle, end, setting, characters, plot, and major points).

Obviously, your strategy should logically relate to achieving your goal. It is a good idea to state your central theme as part of the strategy as well. This gives your client an opportunity to visualize your approach. Your client should not be left to wonder how your pure creativity is going to accomplish the objective. If the strategy does not make sense to the client at this stage, you are headed for big problems later.

CONTENT

The content need not be a verbatim script, but a general outline of what will happen and when. This should include at least the beginning, middle, and end, as well as the setting, characters, plot, and any major points to be made. Being too specific is as inappropriate as being too vague. It is best to give yourself some creative wiggle room here. Often, some of your original ideas will not pan out. Leave room for slight changes to accommodate ideas that might arise later in production and postproduction. At the same time, avoid being too vague, because the linkage between content, strategy, and goal might not make sense to your client.

For most corporate video projects, a few pages specifying the treatment are sufficient. A complex fiction project with a 30- or 60-minute duration might require a longer treatment, say 10 or more pages, to help convey what the final product will look like. This type of treatment may include descriptions of the locations, characters, and some camera direction, as well.

Outline

Now all the facts, figures, and visual ideas need to be organized so that they will form the skeleton for the body of your project. An outline should simply and succinctly list the points, facts, comments, and visualizations that will tell your story in the appropriate order. You can easily reshuffle your ideas to form the best story at this stage. Allowing your outline to be reviewed by other production team members, other professionals, and even the client may save hours of rewriting, reediting, or reshooting. (See Figure 5.5.)

One convenient way to organize your outline is to use index cards. Use one idea, fact, or visualization per index card and include, when possible, a small sketch or photo to clarify the visual idea. Having these paper cards in front of you to study and arrange in different orders is very useful. However, if you prefer to do all your work on a computer, you can use a sticky notes program or word-processing program to do the same thing, cutting and pasting as you try different arrangements. Arrange your cards or electronic notes in a logical sequence, and then try to tell your story by reading and embellishing on each card or note in the sequence. A few attempts at storytelling in this manner will probably reveal inconsistencies, improper order, and difficult or clumsy transitions that may be hiding in your future outline. Once your cards or notes are in the proper order, construct an outline and allow others to give you some feedback.

FIGURE 5.5

Objectives and outline for a corporate video script. (Courtesy of Allstate Insurance Company)

Script

Now you are ready to write a script that will guide you in shooting the raw footage for your program. At this point your creativity and skill must be fully used. There are some guidelines to keep in mind:

• Visualize the items on your outline. Fill in the gaps between each point; visualize the transitions. How do you get from one step to the next? Think visually; then allow the audio portion of the script to enhance the video.

• Make an effort to capture your audience’s interest very early in the script. Try to “hook” your audience with a compelling audio, video, or combined shot in the introductory part of the script. You need this to keep your audience throughout your project. In a video brochure for a new apartment complex, you might have an opening shot of a terrific view of a nearby mountain peak. Your narration could say something like:

How would you like this view from your apartment? Keep watching and we’ll show you a new living community where every dwelling has a view like this! And if you call the number we’ll give you later in this video, you may win a free year’s lease!

• Consider your writing style. Do not write as if you are lecturing or writing a technical document or a brochure. Make sure that your writing is conversational. It is best to try to create short sentences. This is the way most people talk to one another, therefore, it is appropriate in both dialogue and narration. Another suggestion is to avoid obscure or unfamiliar terminology, unless the narrator explains the terms shortly before or after their use. Make sure that the dialogue or narration is appropriate for the speaker(s). You would not have the president of a corporation say, “Let’s get your butts in gear,” during a motivational video aimed at company workers. The statement, “Let’s combine our energies and talents so we can solve these problems together,” would be more appropriate. A five-year-old would not normally say, “I seem to have developed an intense craving for an ice cream cone.” More likely, a five-year-old would say, “Mommy, can I have some ice cream?” or “Gimme some ice cream!”

• Keep in mind that regardless of the specific goal of the video project, it must tell a story. It should have a beginning, middle, and end, with an appropriate story line that attempts to meet your objectives. Make sure that your central visual theme is not obscured by overly complex or convoluted plot devices.

• Know what length of time your video must be and write accordingly. Assume that about 20 words equals 10 seconds of reading time. Each minute will have about 120 words. After the script is written, read it out loud and time it to make sure you are accurate.

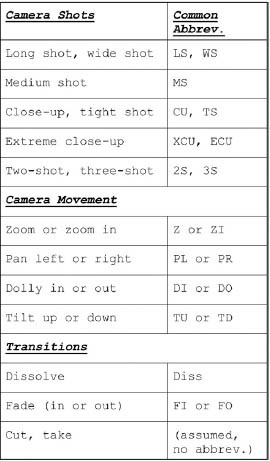

• Include all necessary directions that explain comprehensively how to translate the written words and ideas into video information. The style, clarity, and completeness of the script should enable a competent director who may not have been involved with the planning or scriptwriting to take the script and shoot the program as you intended it to be shot. (See Figure 5.6 for some common production terms used in TV scriptwriting.)

• Expect revisions of your script. No script remains intact in its first version throughout the production process. Your script should be considered a first draft.

FIGURE 5.6

A table with some common terms and abbreviations used in scriptwriting.

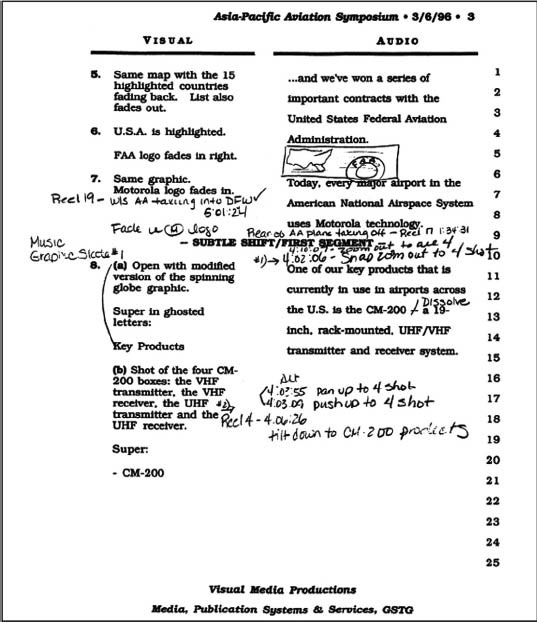

FIGURE 5.7

A script with typical revisions. (Courtesy of Motorola, Integrated Information Systems Group, Visual Media Communications)

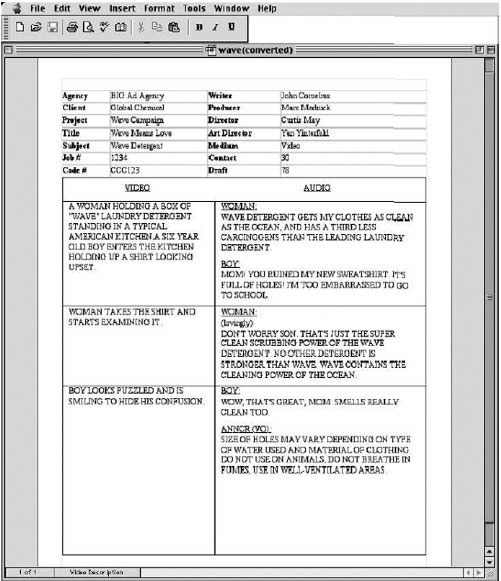

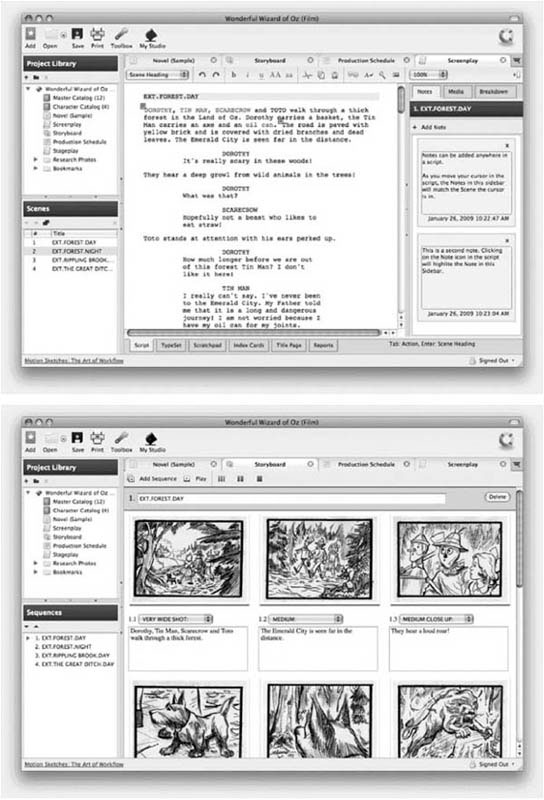

At this point, your script is ready for some fine-tuning in the review process. (See Figure 5.7.) If you feel that your script will be going through many reviews and edits, it might be easier to use some type of scriptwriting program to help you format and edit quickly. Although some word processors have this capability, it may be best to get a program that is designed for writing scripts for electronic media. (See Figure 5.8.)

If you’re not already familiar with scriptwriting formats, read Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. Appendix 1 provides the bare bones of writing single-camera (film-style) scripts or screenplays. Appendix 2 offers the bare bones of two-column, or audiovisual (AV), scripts, including a tutorial on how to use the Tables function in Microsoft Word to set up the two-column format.

Review and Revision

After the first draft is written, most scripts are subject to some sort of review process. For a student or practitioner of video production, this review process is internal. The scriptwriter should reread the script a few days after it is written and reassess its merit. Does it depict the desired mood or concepts in the manner intended? Often, some rewriting is necessary.

FIGURE 5.8

A promotional screenshot from Final Draft, the leading screenwriting software for film and television. This image is from Final Draft A/V, the two-column scriptwriting program. (Courtesy of Final Draft, Inc.)

For scriptwriters in corporate video or any video made for a client, the client generally wants to read the first draft to see if it conveys the desired meaning. In many cases, this review process is not just helpful, it is mandatory. Production often cannot start without client approval of the script. Although it may seem tedious, this review and approval process is a safeguard for the EFP producer and scriptwriter. It often prevents a client from complaining about the scriptwriter’s interpretation of the objectives.

The review process leads to a revised second draft and, sometimes, numerous successive drafts. When a draft is finally approved, it becomes a shooting script and acts as the guide for the actual production work. By having a final script approved by the client, the stage is set for shooting to go smoothly and to stay on schedule and on budget. Of course, a few surprises always come up when actual shooting begins; however, a good script can keep these sometimes costly surprises to a minimum.

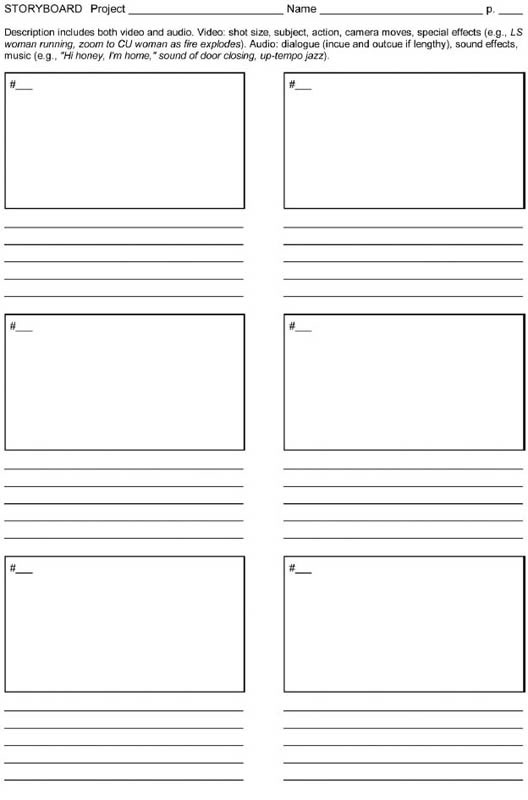

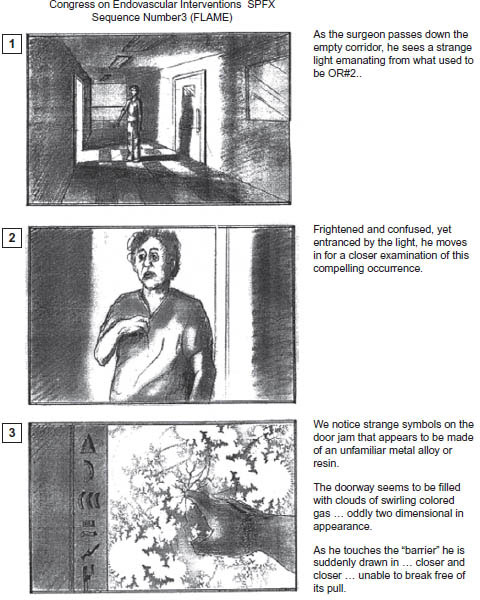

Storyboard

If there is sufficient time and budget, it is recommended that you create a storyboard. This pictorial outline can be drawn up by the writer, director, producer, advertising agency, or even the client. The storyboard is a roughed-out drawing of every scene to be produced in the video. Special pads of paper with blank TV screen outlines on them normally are used to maintain the proper aspect ratio for TV photography. (See Figure 5.9.) With this form, each picture or scene is shown with the dialogue and camera directions directly beneath it. Another layout has the description of the scene to the right of the picture. (See Figure 5.10.) As is the case with scriptwriting, software programs are available to assist with storyboarding. (See Figure 5.11.)

The storyboard allows all crew members and talent to see how the shots should look. This makes it possible for all blocking, props, lighting, special equipment, and special effects to be worked out while the video is still in preproduction. Time and money can be more closely controlled using the storyboard because the entire cast and crew know how the finished product should look. Storyboards help eliminate the shocked comment that occurs when the rough-cut version is shown to the client: “That’s not at all what we had in mind.”

A good storyboard can save time in the long run and can help head off serious problems during production. Even if no one involved in the project can draw, stick figures and rough sketches are better than nothing at all. Alfred Hitchcock never shot a frame of film until it was carefully drawn out in every detail on a storyboard. Steven Spielberg often has drawings of sets and pictures of locations for all scenes before shooting a movie.

If you’re not already familiar with storyboard techniques, read Appendix 3. This appendix provides additional information about storyboarding. It includes the common shorthand and symbols used in constructing the panel drawings and writing the video and audio descriptions.

Editing Script

After the raw footage (a.k.a. source video) has been shot, producers, directors, and writers have another step in the scriptwriting process that is often not available to those in studio TV: viewing the footage for editing. This step allows members of the EFP production team to review all the source video for the shooting script and decide if revisions to the original script are needed.

If changes are required or requested, the script can be rewritten to accommodate the editing process. Shot sequences may be changed, some shots or scenes may be deleted, or some new shots may be added. One of the real advantages of EFP television over studio TV becomes especially apparent if new shots are needed. Although equipment and personnel may need to be rescheduled, costly studio space will not have to be rescheduled. The additional EFP work can be done with as few as two or three crew members. If this reshooting does not involve the principal talent, a second unit might even be employed to do the pickup shots at less expense than the first production unit.

The final version of the script, the editing script, is completed at this point. It is the last step in the production process before the final edit of the program is completed. This step usually involves minor changes to fine-tune the most recent draft of the script and the raw footage into a completed program. It is the script that most accurately reflects the shots and dialogue in the source video. This script is given to the editor(s) to use as a guide in cutting the final program together.

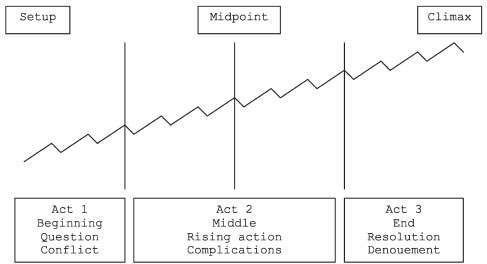

Story Structure Throughout

Throughout the writing process, it is essential to remember that all stories follow the same basic pattern: beginning, middle, end. Screenwriters refer to this as the three-act structure.

FIGURE 5.9

Blank storyboard page to be copied and used.

FIGURE 5.10

This storyboard from a hospital video has descriptions of each shot at the right. (Courtesy of VAS Communications)

Act 1, the beginning, sets up the story. Act 2, the middle, moves the story forward with more detail, introduces complications, attempts to answer questions, and so on. Act 3, the end, brings the story to its conclusion. Whether it is a 30-second commercial, a 90-second news package, a 10-minute corporate video, or a 2-hour movie, each production starts somewhere, goes somewhere, and finishes somewhere. (See Figure 5.12.)

THE BEGINNING

Each story must start somewhere, so why not at the beginning? What happened first? Where? How? In visual terms, you can generally think of the beginning as the wide shot—the shot that establishes the content of the story, the relationships among the elements, or the feeling and tone of the topic. Most things happen along a timeline; you would not show the outcome of the race and then show some of the racers still running or even starting. Things should be shown in the order in which they occur.

There should be a sense of positive time flow within the story, as if we are seeing an encapsulated version of what took place. The beginning should initiate the story and make the viewer want to see more of it. Aim to spark a viewer’s attention, or at least enhance it, by the opening sequence of the story line. The question “What’s next?” should always be present. Try not to lose the viewer’s attention; the audience should always be anticipating the next element of the story.

FIGURE 5.11

Screenshots from Celtx, a free screenwriting program. These images show the screenplay (top) and storyboard (bottom) views. (Courtesy of Celtx)

FIGURE 5.12

Diagram of the basic three-act story structure.

A good way of securing a viewer’s attention is to establish a sequence of action to follow. A story about a school building that is going to close need not be a collection of building shots. Instead, you can open the story with a shot of children entering the building. By doing this, you have the wide shot of the building, but the added element of kids entering the building within that shot has now started a story line. Very simplistically, you have posed these questions: Where are the kids going? What are they going to do? These are questions that you as editor and photographer can answer visually.

In this example, these questions would not be pressing in the minds of viewers, yet they establish a basic story line. Try to present a situation that needs further information or investigation to satisfy the viewer. Show the subject doing something or moving so that the activity or direction can be explored more fully. The start of a story can have a symbolic opening. The big fire piece could start with the sound of screaming sirens over a tight shot of flames. The scene is set with the elements: fire and firefighters. Audience interest is piqued: What’s burning? A beginning must always appear to be headed somewhere. Invite the viewer to follow your lead. Make the viewer consciously or subconsciously ask, “What’s next?” or “Why?” or “How?” and then proceed to answer the question. The beginning has to be the grabber, the hook. If you lose the viewers’ interest at the beginning, they will never make it through the middle.

THE MIDDLE

The middle is the guts of the story, the development of the idea started in the beginning. Once the race has begun, how is everyone doing? In visual terms, as the wide shot is to the beginning of the story, so the medium shot is to the middle. The elements established at the start are now explored in greater detail and examined as to how they can further the story. Complications arise. Questions are posed. The story moves forward.

As the middle progresses, use rising action, making each segment more dramatic, intense, or gripping than the previous segment. Screenwriters refer to this as “raising the stakes.” In a fully scripted EFP production, for example, this could be sending the main character on a journey in which each scene is more dangerous than the last. In a partially scripted ENG project, for example, this could be revealing facts about the story in a progression that keeps whetting the viewers’ appetite for the next segment, much like an appetizer prepares us for the soup, which in turn prepares us for the main course, which might be followed by dessert. The ever-intensifying middle of a story holds the viewers’ interest, leading them to anticipate the end.

In our school-closing story line, showing the reasons for this closure would make up the middle. Possible ideas, stated visually as medium shots, are half-full classrooms (low attendance), students sitting amid dilapidated surroundings (disrepair), or city officials arguing over cost (budget). The middle is obviously the longest segment of any story. It develops the ideas. There might be characters for the audience to learn about, situations to understand, or motivations to feel. Write with one eye toward leading the viewers on a journey and the other eye toward segments that videographers can capture with descriptive shots to build interest.

THE END

Every story should come to some sort of conclusion. The element that hooked the viewers at the beginning and all the elements that raised the stakes of the story throughout the middle now come together at the climax—the moment when your audience receives its payoff for watching. All questions are answered. All conflicts are resolved. Typically, the climactic moment is followed by a final shot or two to reduce the intensity and bring closure to the piece. The fancy word for this moment after the climax that brings finality is the “denouement.”

The climax might be a big moment, such as an explosion or car chase, or it might be a more intimate moment, such as two people realizing their love for each other. In the race analogy, the climax is simple: The winner crosses the finish line. The denouement might then be a shot of the winner receiving the trophy. In the school-closing story, the climactic resolution would be the last answer to the question of why the school is closing, perhaps followed by a final shot of the children leaving the building and the doors closing. A story about taxis could end on a shot of a cab pulling away from the camera and driving off down the street—the old riding off into the sunset idea (negative motion).

Whether it actually comes to an end, or the sun simply sets in the last shot, the story must finish in some way. Even if there is no real conclusion or end, the appearance of one is desirable. The idea started at the beginning must be brought to completion or resolution in some way. The end might be displaying a finished sculpture, sealing up a box, closing a door, the crowd applauding, a skyline shot of the city, or anything that says, “The End.” The more thought put into how the story will end, the better the chance the viewers will come away with a feeling that the story is complete.

SUMMARY

Scriptwriting is one of the most important steps in the preproduction planning of any video project. Scripts are the blueprints from which videos are made. For news (ENG) and interview projects, whether hard or soft news, the writer is mostly concerned with questions that will elicit good soundbites from the interviewees. Typical open-ended questions begin with the five Ws and H: who, what, where, when, why, how? The resulting soundbites are then edited into the final piece. The information is traditionally arranged in an inverted pyramid, with the most important information first. The actual script for the finished story, including the reporter’s exposition, is written after the shoot. Once the footage has been reviewed, the reporter can “write to the visuals,” filling in with words where images are incomplete, but not overscripting when the visuals tell the story. Attention to the details of good, visual, conversational writing style is critical.

For other types of projects with plots, characters, dialogue, and so on (EFP), the writer creates a full script. Before creating the script, a number of items must be considered and committed to paper: goals, audience, format and style, central visual theme, research, treatment, and outline. Once critical decisions have been made regarding each of these items, the script can be written—and then, of course, reviewed, revised, and rewritten as many times as is necessary for final approval by all concerned: client, producer, director, writer. The final, approved script becomes the shooting script for the project.

If time and budget allow, a storyboard is recommended to give all concerned an idea of how the project will look visually. Also, during and after the shooting phase of production, the footage can be reviewed for editing, and additional script changes can be made, resulting in a final editing script. Throughout this writing process, attention must be given to a satisfying story line that follows the basic story structure: an interesting beginning, an intensifying middle, and a rewarding end.