Introduction

Welcome to the world of portable video! So you have access to a camera, a tripod, some lights, a microphone or two, and some editing software on a computer. What do you do? Where do you start? What do you need to know? This book is designed to give you the basics of portable video production. We hope this text will guide you as you create more professional-looking video stories for news, entertainment, and nonbroadcast uses.

Experiments using electricity to transmit video began back in 1884. In 1926, English experimenter John Logie Baird developed a system for transmitting live video images using a mechanical system. The mechanical system was primitive by today’s standards, and other methods were explored to achieve a better picture. Beginning in the 1920s, other experimenters attempted to use an electronic system for television. Philo T. Farnsworth and Vladimir Zworykin both developed systems that eventually were combined to create the working television system that debuted at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

ENG AND EFP: THE WORLD OF PROFESSIONAL VIDEO

Portable video systems have been around for a long time. In 1965, Sony released a video system called the Porta-pak that recorded black-and-white images on a reel-to-reel videotape recorder. The quality was poor and the video was almost impossible to edit. Some educational, government, medical, and experimental users (video artists) found the Porta-pak helpful in capturing images quickly where film would be too expensive. Mostly, however, professional filmmakers and others who needed to capture moving images relied upon film and thought of portable video as a toy with limited appeal. During the 1960s and early 1970s the idea of shooting field video with a portable camera was not feasible, even after color cameras were introduced. The equipment was just too big and cumbersome, and the video was lacking in quality compared to film.

The appearance of the U-Matic videocassette by Sony in 1971, coupled with the introduction of higher-resolution color cameras, rapidly gave portable video a new appeal. This self-threading cassette system, in a machine small enough to be carried around and operated by battery, replaced the Porta-pak’s reel-to-reel system and greatly improved the quality of the recording. The camera was in two pieces—the camera head and the camera control unit (CCU)—both of which could be powered by a battery. Two people could easily walk around with the gear and record video. With the equipment mounted on a small cart, one person could operate the system.

FIGURE 1.1

Philo T. Farnsworth and his model Mabel with a 1935 portable video camera.

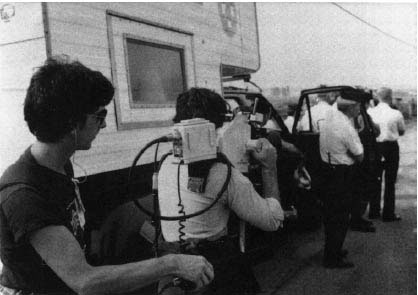

FIGURE 1.2

This early ENG camera, the Thompson MicroCAM, required two people to operate it in the field. (Courtesy of Larry Greene, KCBS-TV)

FIGURE 1.3

News photographers in 1980. Each full set of gear weighed about 80 pounds. (Photo by Joe Vitti)

The TV networks, knowing the power of video cameras in news and sports coverage, began to experiment with this new portable technology—even though their use was limited by their size, miles of cables, and often days of setup time. Companies like Sony, Thomson, RCA, and Ikegami worked closely with the networks to deliver a smaller, higher-quality camera that could meet their needs. Their primary focus for use was live TV and, in particular, sports. A smaller battery-powered camera could increase the coverage of a sporting event dramatically.

One of the earliest uses of portable video in network news was President Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1974. CBS decided to use video instead of 16 mm film to cover the event. The electronic news gathering revolution had begun. The 1976 CBS coverage of the presidential campaign put portable video cameras in the mainstream of news coverage. Reporters no longer had to wait for the 16 mm film to be developed to view, edit, then air the story. They could now report live from campaign stops with the use of these new camera units, or shoot tape and have it aired almost immediately. But an even more dramatic industry change was already underway.

Starting with early experiments at stations such as the CBS-owned and -operated (O&O) KCBS in Los Angeles in 1974, video slowly began to create a foothold in daily news coverage. In 1974, KMOX-TV (now KMOV-TV) in St. Louis became the first all-video, or all ENG, newsroom in the country, using the Ikegami HL-35 two-piece camera. This novel approach to covering local events became an important factor in the competitiveness of the station’s news ratings. By the second half of the 1970s, the video revolution began sweeping local television stations across the country. This triggered the beginning of the electronic newsgathering revolution.

Fueled by the realization that there was money in news because news had a big and growing audience, more and more local TV stations started news shows or began aggressively expanding their news operations. At the local level, it no longer mattered whether a network’s programming was the highest rated; what mattered was how big the audience—and therefore the advertising dollars—was for the local news show. The competition became fierce. Station and network management looked for any means to gain a competitive edge in news. The ability to get a breaking story on the air first epitomized the race. Suddenly, the newly downsized video camera and its videotape recorder were just what the doctor (or station owner) ordered.

The newfound portability of both the video camera and the videotape recorder, which was being demonstrated at CBS and local stations like KNXT, KMOX, and WBBM (in Chicago), was now revolutionizing the film-dominated daily television newscasts in two very important ways. First, it was possible for a videocassette of a breaking news story to be delivered to the station and, after just a few minutes of editing, be played on the air. Faster yet, the raw or unedited tape—which didn’t have to be developed—could be put directly on the air, allowing the viewer to see a video presentation only minutes after it was shot. Second, because the camera was now electronic instead of mechanical, its video signal could be broadcast live from the field with little setup or fuss. This process was aided by newly developed microwave technology, which could easily send the video to the station for broadcasting. Live TV news on location was suddenly available to almost any station at a reasonably low price. These technological changes affected not only the look of the industry, but the various ways in which stories were covered.

This new form of acquiring images—and consequently the whole business of television news—became known as electronic news gathering, or ENG. As the news ratings race continued at an ever-increasing pace, the demand for better, lighter, and more reliable camera gear also grew. Companies rushing to supply news departments with the latest advance in equipment began finding new outlets for their products. Mass production, better technology, and competition within their own industry had made video equipment cheaper and therefore more accessible to a wide range of users. Hospitals, government agencies, corporations, educational institutions, and independent production houses began to replace their film cameras with video cameras. Organizations that didn’t have any production capabilities suddenly found that producing their own video projects was cost effective because of the decreasing price of video equipment, the ease of use of the equipment, and its ever-increasing quality. From hospital teaching tapes to TV commercials, any use of a single video camera with a portable videotape recorder that wasn’t for a newscast became known as electronic field production, or EFP. The similarities between ENG and EFP are many. Generally, the equipment and its operation are the same, but the style of shooting and the production goals often separate the two.

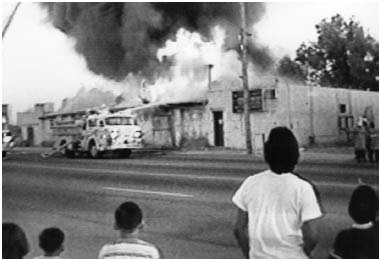

By the 1990s, high-quality video camcorders (camera and videotape recorders in one unit) had not only become affordable to the general public but had also become commonplace. This invention created a world where almost no event goes unrecorded. Whenever something important or newsworthy happens anywhere in the world, it is usually captured on video by someone. One of the most famous—or infamous—events was the 1991 police beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles, which was captured by an amateur videographer trying out his new camera from the balcony of his apartment. That home video began a chain of events that led to one of the worst civil disturbances in the history of the United States. It also secured the video camera’s place as a powerful tool for a free society’s ability to communicate. Some might say that single moment was the culmination of the TV revolution: the fullest realization of the power of television and its profound effect on society. Since that historically significant amateur recording happened, many instances of citizens capturing events both newsworthy and not-so newsworthy (most of those on YouTube) have occurred. Cell phones with the ability to capture video have been used in many parts of the world to show the tragic impact of tsunamis, the horrors of war, and civil unrest.

It is with this power in mind that the video professional sets about the job of creating news, entertainment, and commercial products. When used properly and with ethical guidance, video can be a very persuasive and informative method of communication, regardless of the delivery system. Video is no longer only for broadcasting and industrial/educational uses; it can be used by anyone in society. With the broadening opportunities for streaming video on the Internet, podcasting, uploading to YouTube, and video blogging (vlogging), anyone can have his or her own TV “station.” Learning and understanding the tools and techniques of the trade can make a videographer an integral part of any modern communication medium, whether it is a commercial broadcast television local station, network, cable, or satellite; YouTube or any web site on the Internet; or an as-yet unimagined delivery system.

FIGURE 1.4

Shooting home video has been a common activity in millions of homes since the 1980s.

FIGURE 1.5

Home video–captured scenes can sometimes be sold to local TV stations, network news programs, or other TV production companies.

A Brief History

In its purest form, ENG is the art of shooting news—video photojournalism for television or any other medium that can deliver video. It is the descendent of a long tradition of documenting events with moving pictures. As with the still camera, one of the first uses of the motion picture camera was recording historic events. Portable film cameras recorded the trench warfare that consumed the European continent in World War I. Later, a more organized effort by news services and military photographers and film makers would show World War II to movie theater audiences via newsreels shown before the feature film. The advent of television and the growth of television stations in the 1950s caused newsreels to be replaced by broadcast television newscasts, but the style of shooting had changed little from the fields of France in World War I to Edward R. Murrow’s post–World War II reports that were beamed into 1950’s living rooms. The camera operators were a very select group of people who followed a tradition of portable image capturing from generation to generation.

The TV news industry grew rapidly in the 1960s, and the style of shooting began to change. Up until then, the film cameras used were rather large and heavy, so most shooting was done from a tripod in controlled situations. Small handheld cameras had no audio recording capabilities and were used mostly in hard-to-get-to places, such as in airplanes or on battlefields. The lighter sound-on-film cameras of the 1960s, such as the Cinema Products CP-16, allowed camera operators greater freedom of movement without having to leave sound or quality behind. The handheld shot became more important. The cameraperson could now be closer to the action than ever before and also capture audio. The introduction of color-reversal film, which could be developed as fast as black-and-white film, added a new sense of reality to every newscast. But it was video that upended decades of tradition.

In the late 1970s, video cameras were introduced in broadcast stations and networks and film cameras left, as did many of the film camera operators. People who were trained in the art of cinema and experienced in the business of journalism were suddenly replaced by engineers from the studio who knew how the electronics worked in the camera but not much about “shooting” or journalism. News events couldn’t wait for these people to learn the craft, so stations and networks had to accept the new priority: Just get any shot that helps tell the story. The video revolution was painful, not only to the displaced workers and confused managers, but also to the viewing public. Pictures on the evening news went from sharp, clear images in realistic color from film shots, to dull, muddy visions with smears lagging behind moving objects and colors ranging from orange to bright green with video. Sometimes it seemed that the operators were trying to master the technology first and find a good shot—or any shot—second. A lot of the respect for the visual part of TV news was lost when the film/video changeover occurred.

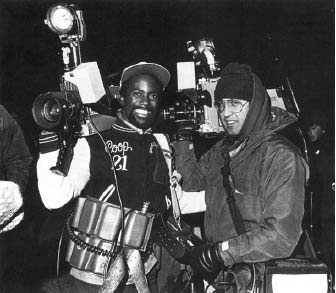

FIGURE 1.6

A two-person ENG crew on location at a military installation. (Courtesy of Hank Bargine)

TV News Videography Today

By the late 1980s, after more than a decade of struggling for acceptance, the news videographer (also known as a TV photojournalist) had come into his and her own. Many people still believe film looks better than video, but the people shooting video eventually reached the same creative level as their counterparts in film. Tune in to any network news magazine show (e.g., 60 Minutes or Dateline NBC), and you will see state-of-the-art creative photography that just happens to be shot on video. There are still plenty of examples of bad videography in local (especially small market) TV news programs. The inclusion of bad video in the newscasts stems more from the changing nature of the news business than anything else. The proliferation of news outlets, the relentless competition, and the almost unrealistic deadline pressures of live TV have allowed quality standards to become a secondary concern at times. Also, TV news shows often have lots of time to fill, but not many visually interesting stories available.

If there is one driving maxim in the ENG world today, it is this: “Any image that can be recorded is better than no image at all.” To understand this statement, you must understand the nature of modern video photojournalism. Yes, quality is important—very important—but nothing is as important as capturing the event. Bringing back the story is the ultimate goal. Because news cannot be planned or controlled—that is, staged—each on-location shoot is different. Decisions have to be made on a case-by-case basis, and often on a second-by-second basis. This book provides guidance for using a video camera in almost any application. But, specifically for the future news videographer, it will be a guide to making those quick decisions as well as to making creative choices that will set the videographer apart from the competition.

Many concepts differentiate ENG videography from any other form of shooting. The primary one is mentioned earlier: The event being covered is the most important thing. You can’t go to the scene of a fire and not bring some video back. A news shooter’s mandate is to find any way to bring back the story. Beg, borrow, or buy whatever you need to get the shots necessary to tell the story (within ethical considerations). There are five other areas in which a news shooter has a unique concern:

• Time

• Control

• Preparation

• Story line

• Responsibility

TIME

People who work in TV news have the sound of the clock pounding in their ears. On a normal day, the pressure builds as the time of the newscast draws closer. The show goes on at exactly 5:00 or 6:00, whether you’re ready or not. And not being ready is a crime with a stiff penalty—one that can easily include termination of employment. A videographer’s entire day revolves around when things take place, how long they last, and how long it takes to get to the next locale or back to the station. The press conference will take place at 10:00 AM sharp. The noon interview at the school lasted one hour. The 3:00 PM story about illegal immigrants has to be shot one hour away from the station. How everything fits into the day, and what can be done at each location, is determined not only by its importance, but also by the time involved.

The situation is doubly confounded when the story is breaking at the moment, such as a plane crash. A news shooter must constantly be aware of the time he or she is spending getting to the location, making the shots, and getting them on the air. It may involve driving them back to the station, driving to meet a microwave van to “feed” the pictures back to the station, or waiting in one spot for the van to arrive. Which method gets the pictures on the air the fastest? How far away is the station, the van, another videographer? On top of the pressure to shoot good video, the videographer must always be apprised of the time it takes to get the footage back to the station. The latest trend is for the video journalist to have a laptop that not only can edit the story at the location, but, with the aid of an “aircard,” can upload video to an Internet site that allows a news producer to download the story for airing.

CONTROL

The next factor that sets a news shooter apart from other videographers is the idea of control: basically, there is none. News videography, with very few exceptions, must follow the mandates of good journalistic ethics. At the heart of those ethics is the rule against manufacturing an event or scene. In other words, you don’t cause anything to happen that would not normally be happening. You can’t go to a protest gathering and tell the participants that it would make better pictures if they marched around the building chanting. You can only show up and shoot what’s there. If it’s dull, then it’s dull.

Applying this rule, as well as working with an entire code of ethics (discussed later in this book) can make shooting even the simplest story a complex task.

What it all comes down to is this: You do not have, nor should you have, any control over your subjects. It’s wrong even to suggest that a housewife whom you’re shooting as part of a story on stay-at-home moms make a pot of coffee. If you’re asking her to do something she wouldn’t normally be doing at that time of day just to give her something to do so you can have some action to shoot, then it’s a violation. It may seem silly, but if you make an exception here and there, you simply alter what is an accurate representation of the truth. If you get into the habit of arbitrarily “creating” action, then you tend to forget what the reality was in the first place.

PREPARATION

All professional video projects require preparation. What sets the news videographer (or multimedia journalist) apart from other (EFP) videographers is that he or she needs to be prepared for anything. You may haul a full set of lights up to a senator’s office ready to do a three-light formal sitdown interview only to find out the senator is late for a vote and you must shoot the politician in the dark hallway while he walks to place his vote. Having a battery-powered light (sometimes called a sungun) mounted on top of the camera might allow you to get the shots you need. You hadn’t planned on using that unflattering light source, but having the correct exposure, as opposed to a dark, low-contrast shot, is far better when seeing the senator answer important questions on camera. No matter how much planning goes into an upcoming news shoot, anything can change because of the concept mentioned earlier: you have no control.

Since you have no control, you must be prepared for anything. News videographers must have a full and complete understanding of the equipment and techniques available to them. Another thing this book will do is make sure the prospective shooter is up to speed on both of those points. The last thing necessary for good preparation is practice. Unfortunately, this book can’t create that experience, but it will suggest how to get it.

STORY LINE

A typical assignment in TV news is to cover an event where little is known about the nature of the subject. A press conference has been called, but the information is vague as to what it’s about—only that it’s important. The videographer working in concert with the reporter, producer, or assignment editor must not only film the event but also understand the event. The script for the story being covered won’t be written until after all the shooting is complete—sometimes hours after the shoot. To obtain the necessary pictures and sound bites that will provide viewers with a clear and concise presentation and fit with the script, the videographer needs to have as much knowledge and detail as possible about the story he or she is covering before and during the shooting. The videographer is the one primarily responsible for visualizing the story.

For example, if the press conference was about a dangerous toxic chemical that was found in the local landfill, then the first thing to be considered is getting pictures of that landfill. Paying close attention to all the details of the story can make a big difference in what gets shot and how. It may be that the source of the contamination is from liquid deposits to the dump. So, in shooting the landfill, most of the effort would be put into finding trucks dumping liquid waste, chemical drums, or any other evidence of liquid waste that is visible at the site. Even with that knowledge, the videographer needs more information. Which companies are doing it? If no one knows, then the shots of trucks dumping liquid waste must be made so that the identity of the company is hidden. You cannot imply wrongdoing by any one company unless they have been accused. One hopes that the writer of the on-air segment will convey the fact that the video seen is not the actual dumping but simply represents the kind of dumping responsible for the problem. You can easily see how shooting without the fullest understanding of the story can lead to more problems (like lawsuits) than just pictures that don’t match the story.

News videographers never shoot in a vacuum. The video will have to be assembled into an edited story at some point. Having the correct mix and variety of shots that cover every aspect of the event or story can make the difference between a visual story line that is hard to follow, or one that speaks for itself. Each picture, every scene, must accurately depict what the videographer wants to convey. Before the videographer begins recording, these questions must be asked:

• Why am I shooting this?

• What does it mean?

• What else do I need to go with this footage to make it a complete story?

• Where will this footage be shown?

RESPONSIBILITY

Despite the fact that a news videographer often works as part of a much larger team—the newsroom—the videographer is often the only person responsible for getting the story. A shooter working alone in a smaller market may be the only one near a major story when it occurs. An event such as a plane crash can put that videographer on the front line of coverage with no reporter or other assistance for minutes or even hours—crucial time when the story must be fully covered. The videographer must not only gather the shots necessary but also gather information, find witnesses and/or survivors who can tell their stories on camera, make contact with the authorities on the scene, and figure out a way to get all this back to the station to be the first on the air with it. That’s why shooters are called photojournalists. It is now common for news footage not only to appear on the nightly newscast, but also to be repurposed. News footage may be used for a two-minute story at the 6:00 PM and 10:00 PM newscasts on one station, and then it may air as part of a larger story in another market, possibly at a station owned by the same station or company that aired the original story. Sometimes footage is requested by a national news service like CNN or Fox News. NBC might use some news footage at a local affiliate station, then in the Nightly News, then again on CNBC, MSNBC, or even Dateline NBC. The footage might also be edited and compressed into a small, digital file for streaming on a news web site or for mobile TV.

Even at the network level, a cameraperson must be able to do all the jobs needed in the field, including being on camera. If you are the witness to a major event as well as its videographer, then you may be called on to give your firsthand accounts to the audience, perhaps even live from the field. No job in the news business should ever be considered strictly someone else’s. But more than anyone else, the videographer is in the position to do it all. After all, television without pictures would be radio.

This certainly doesn’t preclude the videographer from being a team player. The overwhelming majority of time, it really does take all those people to put a good show on the air. It makes for a better product when each member of the team concentrates on being the best at what he or she does and lets others be the best at doing their jobs. However, as with so many other aspects of news, you must also plan for the worst-case scenario. For the videographer, that means being prepared to go it alone. Recently, the videographer has also become the stand-up talent, videographer, interviewer, light person, audio person, and editor.

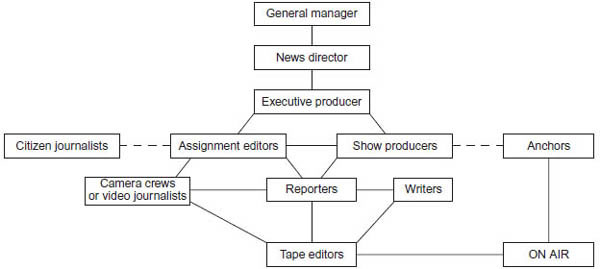

FIGURE 1.7

Typical newsroom chain-of-command flowchart.

Being a news videographer or multimedia journalist can be the greatest job in the world. It involves seeing history as it is made, experiencing the drama of life up close in a way that very few in this society will ever do, going places that few will ever get to see—and being paid to do it. Armed with about $15,000 worth of equipment in video/photo cameras, a laptop computer with editing software, and an Internet uplink capability, many “videographers” have become one-man bands or multimedia journalists … writing stories, shooting video and taking photos, and collecting audio from neighborhood crime scenes to combat zones like Iraq and Afghanistan.

ELECTRONIC FIELD PRODUCTION: VIDEO PRODUCTION ON LOCATION

Birth of an Industry

The techniques used in portable or field video were not invented by those who began to shoot ENG in the late 1970s. These techniques began in the early days of filmmaking when a single (film) camera was used by cinematographers to record drama or comedy to create feature films. This style of shooting became known as film style or single-camera shooting. These cinematographers developed the technique of shooting a scene from one camera angle, then shooting the same scene from one or more different camera locations or camera angles. After the film was processed, a film editor would edit various parts of the different takes together to make one version of the scene. The scene would have smooth action, and it would appear as if there were numerous cameras all shooting the same scene at the same time.

The need for doing the production in this fashion was much the same then as it is now. One camera can achieve an aesthetically pleasing scene that appears to have been shot by multiple cameras. Good cameras were expensive, and multiple camera productions were not cost effective. A good filmmaker could create a film that had a big-budget look by using a small-budget crew and camera.

As news evolved from simple documentation to more comprehensive storytelling via newsreels, only a few others outside the movie industry were making use of the moving picture. Filmmaking was expensive, time consuming, and had relatively few practitioners. With the advent of television and smaller film formats like 16 mm and 8 mm, more organizations and even consumers began to use the medium. Health and science films produced by the government and shown on chattering 16 mm projectors became common in the classroom. Home movies became a symbol of middle-class success.

But it was the video revolution started by the news competition that sparked a whole new industry. Based entirely on the new portable video systems, electronic field production, or EFP, was born. Suddenly, for a slightly larger initial investment in equipment, the cost of shooting a minute’s worth of moving pictures went from being measured in dollars to being measured in pennies. Without the punishing conditions of news coverage, the equipment could be easily maintained and, therefore, last longer, so its reliability was no longer a question. Video productions that were once confined to the studio suddenly broke free to take place in almost any location imaginable. Affordable portable video cameras allowed freedom from high costs and limited locations and allowed almost anyone with the desire to communicate a message the equipment to do it.

Video Production Today: The Process

The process of producing an ENG story differs from producing an EFP project. Since traditional ENG is mostly shot on the day the story is assigned, little time is available for preparing for the location and the shoot. The shoot occurs where and when the event is happening. Preparation for ENG is discussed in Chapters 2 and 6.

In EFP, much more time is available for the videographer to prepare for the shoot. The process is discussed in both Chapters 3 and 6. For nonnews production, the general process and stages of production are the same three phases they have been for many years: preproduction, production, and postproduction.

THE THREE PHASES OF PRODUCTION

The first phase of production, preproduction, is perhaps the most important for the success of the project. At this stage, a client who needs a project produced contacts a company or producer who can produce video projects. The project is discussed and client goals are decided. A producer then begins research for the project and the script by creating a script outline, a treatment (a synopsis of the project), a storyboard (individual pictures or drawings of the scenes in the project), then the script. A crew is selected that includes people who will perform the functions of producer, director, videographer, actor(s), and production assistants (also known as PAs or grips). In large productions, there may also be people selected to do makeup, set lights, collect audio, and perform other necessary functions. A video editor is also selected. Once the script is written (and approved by the client), the location(s) is selected, schedules are created, then rehearsals can begin. This phase takes 60 to 80 percent of the total time spent on the project.

The second phase is production—the actual recording of the video for the project. Once all the decisions have been made about the script, location, equipment, and crew, the actual shooting can begin. The talent rehearses, the equipment is set up, the crew takes their places at the shoot location, and once the director is satisfied that all variables are correct and under control, the shooting can begin. This includes not only shooting the main action and characters, but also shooting additional shots, such as cutaways (shots relating to the main action), that might be helpful in the editing process. A good producer will not leave the location until he or she is sure that all the shots needed at that location have been recorded.

The third phase of production is postproduction. This is the phase when the “raw footage” or unedited video is combined to make the project that was planned. It involves putting the shots and scenes together to tell the story and making sure that the shots look right and sound right. The key person in this phase is the video editor who does the actual combining of the shots to make the story come together properly. The script is the blueprint for the project, and the editor, along with the producer, work to make the video match the script. Although some creative choices might differ from the original script, the video project should follow the script as written. The client sees the project after it is edited and either approves it or suggests the changes necessary to make sure that the project meets the client’s goals. We will discuss more on this stage of the production process in Chapter 7.

As you go through this book you will notice the similarities between ENG and EFP. The equipment is basically the same. The shooting aesthetics are the same. The basic principles are very similar. Ideas and concepts in one discipline can easily be applied to the other in many cases. Learning news videography prepares you for doing most field production work, and vice versa. But there are differences that must be understood. The two production styles are derived from very different goals. In news, the event is of paramount importance, while in EFP, the overriding importance is placed on what the client (who in the case of entertainment is the producer) wants. The sole purpose of the production is to serve the client’s goals, whatever they are. It may be as simple as showing all the new Fords for sale, or as complex as teaching a group of teenagers that violence is not the answer to life’s problems or giving instructions about how to install a new component into your computer. In entertainment programming, the goal may be to scare, mystify, or get the audience to laugh or otherwise enjoy the program. Whatever the subject, the goal is to communicate the message of the client.

ENG has many differences when compared to EFP. Most of these differences simply involve the reordering of priorities. Some involve approaching a situation from the exact opposite point of view. The following areas are of concern to a field production videographer:

• Budget

• Planning

• Script

• Authority

BUDGET

If time is the driving force behind the news videographer, money is what drives the production videographer. Before any work is done, a budget is set in place. Going over budget can result in people and bills not being paid—not the kind of thing you want to happen in the business world. In EFP, you can say that time is money. This is especially true when it comes to the hours it takes to get something done. If a flat rate of $1000 is allotted to pay the members of the crew, then each member should have a reasonable expectation of how much work is involved for that amount of money. If the shoot starts to run longer than anticipated, then the hourly salary for those crew members begins to decline. That makes for unhappy workers and, in some cases, workers who walk away from the job in disgust. The producer, the person with the responsibility for getting the project done, has two choices: Go to the client and ask for more money, or cut other items from the budget to make up the difference.

Generating an accurate budget can be one of the most difficult tasks in EFP. As the previous example illustrates, a miscalculation can cause the entire project to fail. Unlike news, every aspect of the production process must be accounted for in that project’s budget. That means figuring in the cost of everything from duct tape to wear and tear on the camera. Chapter 11 explains how to create an accurate budget that will keep you in your job and out of hot water—and possibly out of bankruptcy court as well.

PLANNING

The factor that allows for accurate budgeting is the extensive planning that goes into any EFP shoot. To control the budget, every aspect of the production must be planned well in advance. An accurate assessment of what must be done, how many people will be needed for the crew, what equipment will be used, and any other items needed for the production must be compiled before the shooting begins. Most EFP projects also include editing as part of the overall job. How long will it take in the edit bay? Are you going to need special effects or animation?

In the real world, nothing ever goes quite as planned. A good production videographer should be intimately involved in the planning process. If the videographer is working alone then he or she takes on the responsibility of being prepared for those unforeseen problems.

In larger productions, the videographer may be working for a production manager but still should be included in any planning process. The best planning also includes what to do if things go wrong. What if it rains? Can the shoot be rescheduled? The EFP videographer must always be able to assess each situation and problem and offer constructive alternatives that meet not only the budget, but the client’s goals as well.

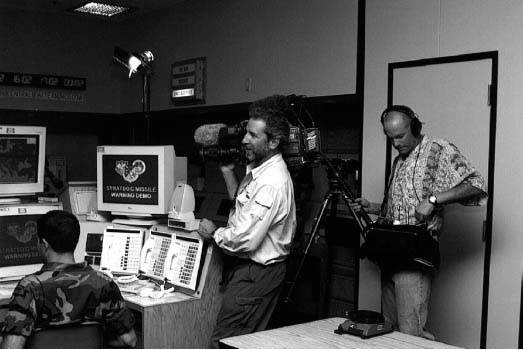

FIGURE 1.8

This EFP crew is shooting a documentary while dealing with extreme weather and an inquisitive (and dangerous) onlooker. (Courtesy of Hank Bargine)

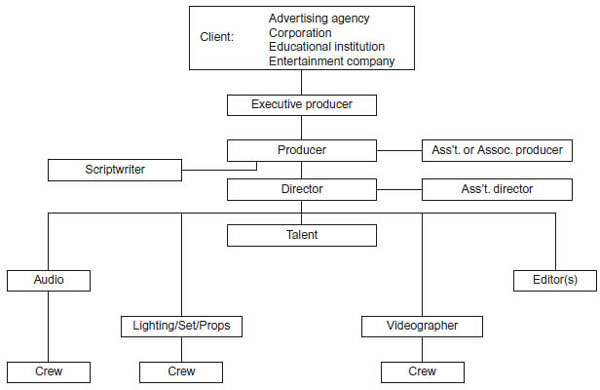

FIGURE 1.9

Typical EFP chain-of-command flowchart.

SCRIPT

The blueprint for what will take place in the field and in the edit room is the script. Nothing gets done without one. The script, just like the blueprint for a new building, gives everyone the guidance they require to get the job done. In larger budgets and more sophisticated productions, the script is visualized in a series of drawings called the storyboard. Each shot is sketched out so that every member of the production team knows what the finished product should look like. In smaller production crews the videographer/director should have a well-defined image of what the look should be. How the shots are made, their framing, the camera movement, the action within the frame, and the lighting are all determined by the script, either directly or by interpretation.

A public service announcement (PSA) on boating safety may have a script calling for scenes of a boating accident. The producer and/or the director with the cameraperson will go over each sentence, indeed every word, of the script to find ways of illustrating the message being conveyed. Within the confines of the proposed budget, they will design shots and scenes that depict what the script is saying. They will identify locations for the shooting to take place, determine how and where the camera should be positioned, determine what kinds of actors and props are needed, and how the action will be framed. If the script includes a concept that, for whatever reason, can’t be depicted directly by a specific shot (e.g., the emotions of a victim’s family), then visualizing it can be a creative challenge. That’s when the production team and the talents of the videographer are stretched. The shots must now be symbolic of the message being delivered. They must convey the emotion of the script. Seeing a hand toss a wreath onto the water may be all that’s necessary to cover the narration describing a family’s grief.

AUTHORITY

The final approval of all aspects of a production shoot comes from the client. The client can reject the script, the actors, a particular shot, and even the videographer. The producer acts as the representative of the client in the client’s absence. The producer makes all the decisions before, during, and after the shoot on authority of the client. The production videographer must understand his or her responsibility within that framework. It can be considerable or minimal. The EFP shooter needs to determine the shooter’s level of authority as soon as possible when a production starts.

In a large organization, the videographer’s duties are generally limited to work associated with the camera: designing and setting up shots, lighting, and executing the shot. The videographer won’t have the burden of total responsibility for the project. In smaller productions, the videographer may be the producer, writer, sound tech, and even actor. Here the shooter-as-producer will have to get the entire job done. What the EFP cameraperson must be able to do in any size organization is offer help and assistance whenever necessary. If the producer can’t solve the problem of a shot that just doesn’t fit the script, the videographer must be ready to step forward and offer a possible solution based on knowledge of production and creative solutions.

Being a production shooter in today’s ever-changing field of video can be both exciting and challenging. As multimedia becomes more common in our communication with each other, there will always be a growing demand for video products. Unencumbered by the constraints of journalism, EFP videographers can explore the outermost limits of their creativity. They can reach into the highest realms of visual art.

KNOWING THE BASICS

At this point, you should know about some of the differences between ENG and EFP—and also know the similarities. In the real world, almost any job you get involving portable video will include a combination of both disciplines. The news shooter might also work on commercials and PSAs done by the in-house production department at the station. The production shooter will be assigned a shoot that the client wants done ENG-style or perhaps to shoot a documentary-style program. In today’s marketplace, many working videographers are freelancers (they work for themselves). The phone rings and they’re off to a job that may last one day or one week. One day they work for ABC World News Tonight, the next day they’re shooting a commercial for the local candidate for governor, and the day after that they’re doing a training video on a new assembly line at an electronics plant. They could also be shooting a segment for a show on HGTV on any given day. The type of shooting depends on who is paying them that day.

As the Internet and other forms of delivery continue to expand, the demand for videographers will grow just as fast. As the world of digital video grows, the potential uses of that video also grow. Streaming video, webcasting, TV-on-demand, DVDs, interactive TV, podcasting, vlogging (video blogging), video to cell phones, and broadcasting are all slowly becoming one and the same. But no matter what the format, no matter what the recording media, no matter what the delivery system, one thing will never change: It will always be videography—that is, capturing images electronically and storing them for later use.

In the following chapters, this book gives you a complete course in the basics of videography. Since all forms of shooting share the common goal of telling a story, the methods and principles of storytelling are the same no matter how the story will be sent or viewed. By learning the basics, students or beginning-level TV photojournalists can quickly learn to provide a certain level of quality in their work. Recipes for success come from the rules and formulas established over the years in news and production videography. They are a guide to get the novice cameraperson on the road to finding that elusive thing called style. Individual style is what creates truly unique views that make videography an art.

SUMMARY

ENG and EFP shooting have a long and rich tradition. Film cameras were used to record news events and to create narrative stories from the early twentieth century. Beginning in earnest in the 1970s, videotape (which had been invented earlier but needed to become smaller and more reliable for day-to-day use) replaced film for news and other small-budget videos because of its lower cost and because it could be played back instantly without first having to be developed like film. In the new millennium, tapeless recording—recording digital video files directly on solid-state recording devices with microchips—is replacing videotape.

Whatever the technology of portable video, the demand for more and more video content will only increase as the means of distributing news, information, and entertainment increases. Vlogs, podcasts, webcasts, as well as more traditional satellite, cable, and terrestrial broadcasting all require video product. With the size and price of cameras continually decreasing, along with the higher sophistication and lower price of editing software, just about anyone can create video content today. In fact, by 2011, 48 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute of every day. YouTube videos are viewed 3 billion times each day.

Whether creating news or nonnews projects, the video producer must be trained in an arsenal of skills if he or she is to communicate the desired message of the video effectively to the intended audience. Each chapter in this book addresses an area within that arsenal. These chapters are organized into four parts or clusters:

Shooting Video on Location

1. Introduction

2. Electronic News Gathering

3. Electronic Field Production

The Process

4. Framing and Composition

5. Scriptwriting

6. Preproduction and Production

7. Postproduction and Distribution

8. Video

9. Audio

10. Light: Understanding and Controlling It

The Business of Video

11. Budget and Pricing

12. Laws, Ethics, Copyright, and Insurance

The first part, Shooting Video on Location, introduces you to the profession, business, and art of portable video. Chapters 2 and 3 define and discuss the two major styles of portable video: electronic news gathering and electronic field production.

The second part, The Process, introduces you to the language of video using basic shots (Chapter 4) and scriptwriting (Chapter 5) needed to build video programs. Chapters 6 and 7 describe the steps needed to plan, shoot, and edit a video project.

The third part, The Tools, gives you in-depth information about the equipment and techniques that you need to know to create high-quality video using consumer or professional equipment.

The final part, The Business of Video, informs you about how projects are budgeted and priced, legal issues that all videographers and producers should know about.

After reading and applying this text, we hope that you will be equipped with the full arsenal of skills necessary to create effective video projects, whether for news (ENG) or nonnews (EFP) projects.