Chapter 2. The Critical Dynamics of Q&A

To fully appreciate the importance of control in handling Q&A sessions, we must start by looking at the consequences of lack of control. Most presenters react to tough questions in one of two ways: They become either defensive or contentious.

Defensive

On April 19, 2007, Alberto Gonzales, the then U.S. Attorney General, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee as part of its investigation of his Justice Department’s firing of eight federal prosecutors. According to a Washington Post report of the hearings, Gonzales used the phrase, “I don’t recall,” and its variants (“I have no recollection,” “I have no memory”) 64 times during his testimony!

The Post report went on to describe Gonzales’ defensive behavior that accompanied his testimony: “For much of the very long day, the attorney general responded like a child caught in a lie. He shifted his feet under the table, balled his hands into fists and occasionally pointed at his questioners.” [2.1]

Another example of defensive behavior came from New York Congressman Anthony Weiner. On Memorial Day weekend in 2011, a conservative blog reported that Weiner had tweeted a lewd photo of himself to a young woman in Washington. The story went viral, becoming what Forbes called, “the perfect storm for news coverage, involving social media, political scandal, and fun word play given Rep. Weiner’s last name.” [2.2]

At first, Weiner dismissed the whole matter as a prank and that someone had hacked his Twitter account, but the perfect storm would not subside. In an effort to defend himself Weiner consented to a number of television interviews, but the more he defended himself, the more defensive he appeared. When MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow asked whether the photo was of him, Weiner responded:

The photograph doesn’t look familiar to me but a lot of people who have been looking at this stuff on our behalf are cautioning me that—you know—stuff gets manipulated. Stuff gets—you know—you can—you can—you can change a photograph, you can manipulate a photograph, you can doctor a photograph. And so, I don’t want to say with certitude it maybe didn’t start out being a photograph of mine and now looks as something different, or maybe it was something that was from another account that got sent to me. I—I don’t—I can’t say for sure. I don’t want to say with certitude and I’m not trying to be evasive. I just don’t know. [2.3]

Contentious

Different people react differently to challenging questions. Although Gonzales and Weiner reacted defensively, others go in the opposite direction and become contentious. One of the most combative men ever to enter the political arena is H. Ross Perot, the billionaire businessman with a reputation for cantankerousness.

In 1992, Perot ran for president as an independent candidate and, although he conducted an aggressive campaign, lost to Bill Clinton. The following year, ever the gadfly, Perot opposed the Clinton-backed North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). His opposition culminated on the night of November 9, 1993, when Perot engaged then Vice President Al Gore in a rancorous debate on Larry King’s television program.

In the heat of battle, Perot launched into the subject of lobbying.

You know what the problem is, folks? It’s foreign lobbyists...are wreckin’ this whole thing. Right here, Time Magazine just says it all, it says “In spite of Clinton’s protests, the influence-peddling machine in Washington is back in high gear.” The headline, Time Magazine: “A Lobbyist’s Paradise.”

I’d like to respond to that.

Larry King tried to allow Gore to speak:

All right, let him respond.

Perot barreled ahead, his forefinger wagging at the camera—and at the audience:

We are being sold out by foreign lobbyists. We’ve got 33 of them working on this in the biggest lobbying effort in the history of our country to ram NAFTA down your throat.

Gore tried to interject again:

I’d like to respond...

But Perot had one more salvo:

That’s the bad news. The good news is it ain’t working.

Having made his point, Perot leaned forward to the camera, smiled smugly, and returned the floor to his opponent:

I’ll turn it over to the others.

Larry King made the hand-off:

OK, Ross.

Gore took his turn:

OK, thank you. One of President Clinton’s first acts in office was to put limits on the lobbyists and new ethics laws, and we’re working for lobby law reform right now. But, you know, we had a little conversation about this earlier, but every dollar that’s been spent for NAFTA has been publicly disclosed. We don’t know yet...tomorrow...perhaps tomorrow we’ll see, but the reason why...and I say this respectfully because I served in the Congress and I don’t know of any single individual who lobbied the Congress more than you did, or people in your behalf did, to get tax breaks for your companies. And it’s legal.

Perot bristled and shot back:

You’re lying! You’re lying now!

“You’re lying!” is as contentious as a statement can be. True to form, Perot showed his belligerent colors.

The Vice President looked incredulous:

You didn’t lobby the Ways and Means Committee for tax breaks for yourself and your companies?

Perot stiffened:

What do you have in mind? What are you talking about?

Gore said matter-of-factly:

Well, it’s been written about extensively and again, there’s nothing illegal about it.

Perot sputtered, disdainfully:

Well that’s not the point! I mean, what are you talking about?

With utter calm, Gore replied:

Lobbying the Congress. You know a lot about it.

Now Perot was livid. He glowered at Gore and insisted:

I mean, spell it out, spell it out!

Gore pressed his case:

You didn’t lobby the Ways and Means Committee? You didn’t have people lobbying the Ways and Means Committee for tax breaks?

Contemptuous, Perot stood his ground:

What are you talking about?

Gore tried to clarify:

In the 1970s...

Perot pressed back:

Well, keep going.

Now Gore sat up, looked his opponent straight in the eye, and asked his most direct challenging question:

Well, did you or did you did you not? I mean, it’s not...

His back against the wall, Perot fought back:

Well, you’re so general I can’t pin it down! [2.4]

Ross Perot’s bristling behavior is matched by Arizona Senator John McCain, a self-described maverick who prides himself for his cantankerous demeanor. When he ran for President in 2008, McCain called his campaign bus, “The Straight Talk Express.” His caustic remarks often gave him the upper hand on the floor of the Senate and in his frequent jousts with the media. But the approach backfired when he debated Barack Obama in a town hall debate on October 7, 2008:

McCAIN: By the way, my friends, I know you grow a little weary with this back-and-forth. It was an energy bill on the floor of the Senate loaded down with goodies, billions for the oil companies, and it was sponsored by Bush and Cheney.

You know who voted for it? You might never know. That one. [2.5]

As McCain said “That one,” he gestured disdainfully at Obama seated behind him without looking at him.

Kathleen Parker, the conservative columnist for the Washington Post wrote that “there’s a reason it was so stunning in the moment. I...don’t think it was racist, as some have argued. But it was objectifying. ‘That one’ isn’t the same as ‘that man.’ One is an object; the other is a person. A human being. ‘That one’ has a dehumanizing effect and one is right to recoil.” [2.6]

One final example of contentious behavior comes from the same Anthony Weiner who provided the earlier example of defensiveness. Pardon the play on words, but Weiner worked both sides of the Q&A aisle.

On July 29, 2010, a little more than a year before the scandal about the tweeted lewd photo, Weiner gave an impassioned speech on the floor of the House of Representatives. The staunch Democrat vehemently denounced a Republican majority vote to defeat a bill that would have provided aid to the victims of the 9/11 attacks:

We see it in the United States Senate every single day, where members say, “We want amendments, we want debates, we want amendments, but we’re still a ‘No.’” And then we stand up and say, “Oh, if we only had a different process we’d vote ‘Yes.’” You vote “Yes” if you believe “Yes.” You vote in favor of something if you believe it’s the right thing. If you believe it’s the wrong thing you vote “No.” We are following a procedure...

At this point in his tirade, another person in the House chamber, off camera, attempted to interject a question or statement. Weiner went ballistic, shouting and gesticulating angrily:

I will not yield to the gentleman and the gentleman will observe regular order—the gentleman will observe regular order! [2.7]

The adjectives defensive and contentious are synonyms for “fight or flight,” the human body’s instinctive reaction to stress. In each of the cases just presented, the response to tough questions was fight or flight. The contentious Ross Perot, John McCain, and Anthony Weiner behaved as pugnaciously as bare-knuckled street brawlers; the defensive Alberto Gonzales and Anthony Weiner behaved like men desperately trying to flee the hot seat.

Presenter Behavior/Audience Perception

Any presenter or speaker who exhibits negative behavior produces a negative impression on the audience.

Alberto Gonzales’ negative behavior produced a very negative impression on Tom Coburn, a Republican member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who told the Attorney General: “‘It was handled incompetently. The communication was atrocious...You ought to suffer the consequences that these others have suffered, and I believe that the best way to put this behind us is your resignation.’” [2.8]

Four months later, the embattled Gonzales submitted his resignation letter to President George W. Bush. [2.9]

It took only three weeks after the Twitter posting for the embattled Anthony Weiner to resign. [2.10]

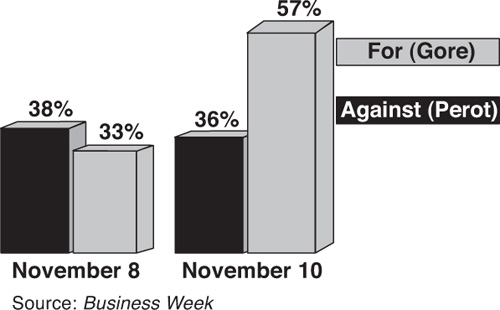

Ross Perot’s behavior on the Larry King Live program also had a profound effect. Figure 2.1 shows the results of the public opinion polls taken on the day before and the day after the debate.

In the 48 hours between the two polls, the only factor with any impact on the NAFTA issue was the debate between the chief proponent and the chief opponent on the Larry King Live program. Ross Perot’s contentious behavior swung the undecided respondents against his cause.

Two months after the debate, the U.S. Congress ratified NAFTA.

As a footnote to the impact of the debate, that episode of the Larry King Live series became the highest-rated program on cable television, a distinction it held for 13 years forward until Monday Night Football moved from over-the-air on ABC to ESPN.

The Six-Million-Dollar Q&A

One other example of negative behavior in response to challenging questions comes from that most challenging of all business communications, an IPO road show. Historically, when companies go public, the chief executives go on the road to pitch investors, and they travel to about a dozen cities over a period of two weeks, having up to 10 meetings a day for a total of 60 to 80 iterations of their road show presentation in each of those meetings.

One particular company had a successful business when they went public. They had accumulated 16 consecutive quarters of profitability. Theirs was a simple business concept: a software product that they sold directly into the retail market. The CEO, having made many presentations over the years to his consumer constituency, as well as to his industry peers, was a proficient presenter. At the start of the road show, the anticipated price range of the company’s offering was $9 to $11 per share.

However, having presented primarily to receptive audiences, the CEO was unaccustomed to the tough questions that investors ask. Every time his potential investors challenged him, he responded with halting and uncertain answers.

After the road show, the opening price of the company’s stock was $9 per share, the bottom of the offering range. Given the 3 million shares offered, the swing cost the company $6 million.

The NetRoadshow Factor

Q&A became even more mission critical in 2005 when the Securities and Exchange Commission mandated that companies offering stock to the public for the first time must make their road show presentation available online. Since then, every company makes video recordings of their executive management teams delivering their pitches and posts them, along with slideshows that accompany their narratives, on a website called netroadshow.com or its companion site retailroadshow.com (see Figure 2.2).

Therefore, by the time the executives of any offering company arrive at the meeting, most of the potential investors have already seen the pitch.

Despite this wide access, the executive teams still make that grueling two-week tour because no investor will make a decision—based on a canned presentation alone—to buy up to a 10% tranche of an offering in the tens of millions of dollars. Investors want to meet the executives in person, press the flesh, look them in the eye, and interact with them directly. As a result, many of the meetings are not presentations at all, but intense Q&A sessions.

All of this harkens back to David Bellet’s observation that investors are looking to see how a presenter stands up in the line of fire. Investors kick the tires to see how the management responds to adversity. Audiences kick tires to assess a presenter’s mettle. Employers kick the tires of prospective employees to test their grit. In all these challenging exchanges, the presenter must exhibit positive behavior that creates a positive impression on the audience.

The first steps in learning how to behave effectively begin in the next chapter.