Chapter 9. Preparation

(Martial Art: Preparation)

The most important part begins even before you put your hand on the sword.

Jyoseishi Kendan By Matsura Seizan (1760–1841) [9.1]

In the martial arts, the discipline required to learn new skills carries virtually the same weight as the skills themselves. Every martial arts treatise sets forth both the underlying philosophy and the rigorous steps required to achieve mastery. The learning progression of karate is marked by the graduated color coding of the uniform belts. Beginners get a white belt; masters get the coveted black belt. It takes years of disciplined preparation and repetition to ascend through all the levels, and only the best practitioners attain the highest level. Learning to answer tough questions is not as daunting as this challenging sport, but if you are about to face a challenging Q&A session, you should keep in mind Thomas Edison’s formula for genius: 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. Prepare yourself thoroughly before you put your hand on the sword.

The NAFTA Debate Revisited

Preparation played a key role in the debate about NAFTA between Al Gore and Ross Perot on the Larry King Live television program that you read about in Chapter 2, “The Critical Dynamics of Q&A.” You saw how Perot flared up when Gore challenged his position on lobbying, but that was only one of many such outbursts during the 90-minute broadcast. Each of the outbursts was provoked by a deliberate strategy that the Gore team had developed in their debate preparation. Their efforts were described in an article in The Atlantic Monthly by James Fallows:

Gore, meanwhile, spent the two weeks before the debate studying Perot’s bearing and his character, while relying on his staff to dig up the goods on Perot’s past...[they] prepared an omnibus edition of Perot’s speeches, statements, and interviews about NAFTA, and also tapes of Perot in action. Gore studied them on his own and then assembled a team at the Naval Observatory—the Vice President’s official residence—for a formal mock debate.

One of the key members of that team was Greg Simon, Gore’s domestic policy advisor. Simon told Fallows about the key strategy that emerged from those sessions:

“If you’re dealing with a hothead, you make him mad...You’ve got a crazy man, you make him show it...He’ll be fine as long as everybody sits there and listens to him, but if you start interrupting him, he’ll lose it.” [9.2]

Gore interrupted Perot repeatedly. In fact, Perot complained to Larry King, to Al Gore, and to the television audience about the interruptions eight times during the first half of the program. By midway through, Perot was steaming mad and operating on a short fuse. He pressed ahead with his cause by turning to the camera and addressing the television audience with yet another blast against NAFTA in general, and Mexico in particular:

All right folks, the Rio Grande River is the most polluted river in the Western Hemisphere...

Right on cue, Gore interrupted:

Wait a minute. Can I respond to this first?

Larry King tried to intervene:

Yeah, let him respond.

By now, Perot was not going to let Gore respond:

The Tijuana River is the most...they’ve had to close it...

Larry King asked:

But all of this is without NAFTA, right?

Gore persisted:

Yeah, and let me respond to this, if I could, would you...

Perot ignored Gore and turned to address Larry King:

Larry, Larry, this is after years of U.S. companies going to Mexico, living free...

Larry King tried to clarify:

But they could do that without NAFTA.

Perot spoke past Gore, directly to Larry King:

But we can stop that without NAFTA and we can stop that with a good NAFTA.

Gore, sitting at Perot’s side, interrupted:

How do you stop that without NAFTA?

Peeved, Perot swung around to face Gore and replied testily:

Just make...just cut that out. Pass a few simple laws on this, make it very, very clear...

Quite innocently, Gore asked:

Pass a few simple laws on Mexico?

His anger rising again, Perot shook his head and then dropped it like a bull about to charge and said:

No.

Gore persisted, quietly, but firmly:

How do you stop it without NAFTA?

Icily, Perot replied:

Give me your whole mind.

“Give me your whole mind.” Perot addressed the Vice President of the United States as if he was an errant employee! The Vice President of the United States smiled back broadly, and said:

Yeah, I’m listening. I haven’t heard the answer, but go ahead.

That’s because you haven’t quit talking.

Gore replied:

Well, I’m listening...

And then for the third time, Gore calmly repeated his question:

How do you stop it without NAFTA?

Perot would not be calmed:

OK, are you going to listen? Work on it! [9.3]

“Work on it!” More disdain and more petulance from Perot. The sum total of all his contentious behavior came a cropper the next day in the public opinion polls: The undecided respondents dramatically swung in favor of NAFTA (please refer to Figure 2.1) and two months later, Congress ratified NAFTA.

Preparation paid off for Al Gore and NAFTA.

Murder Boards

Every nominee for the Supreme Court has to face a confirmation hearing by the Senate Judiciary Committee. These events often become intense encounters because the party out of power wants to do everything it can to make the sitting president—and that president’s choices—look bad.

In preparation for the hearing, nominees spend long hours in mock practice sessions called “Murder Boards,” which include everything from re-creating the setting in the senate chamber to anticipating the worst-case questions from the senators.

The Murder Boards for Elena Kagan, President Obama’s second nominee for the Supreme Court, were described in a post on realclearpolitics.com by political writer Julie Hirschfeld Davis as follows:

For several grueling hours each day, Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan sits at a witness table, facing a phalanx of questioners grilling her about constitutional law, her views of legal issues and what qualifies her to be a justice. They are not polite...Kagan hashes out answers to every conceivable question and practices staying calm and poised during hours of pressure and hot television lights.

One item in the same article that deserves particular attention comes from Rachel Brand, an attorney who helped President George W. Bush’s nominees, John G. Roberts and Samuel Alito, prepare for their confirmation hearings. Ms. Brand said that the purpose of the Murder Boards “‘is to ask those hard questions in the nastiest conceivable way, over and over and over....’” [9.4]

Rachel Brand’s triple iteration of over is the operative point. You’ll recall that Verbalization is the process of rehearsing your presentation aloud as you would to an actual audience. That same practice is just as—if not more—important in handling tough questions. Although it may seem sufficient to list the anticipated challenging questions and to craft an answer for each of them, that is not enough. It is far more effective to have someone fire those questions at you and to speak your answers aloud. And you must do it over and over and over. The dynamics of the repeated interchanges in practice will make your responses in real time crisp and assertive.

The Murder Boards approach worked for Justices Kagan, Roberts, and Alito, and they can work for you. In preparation for your next Q&A session, have a member or members of your team fire tough questions at you and Verbalize your answers to them over and over and over.

Think of it as volleying to perfect your tennis game.

Presidential Elections

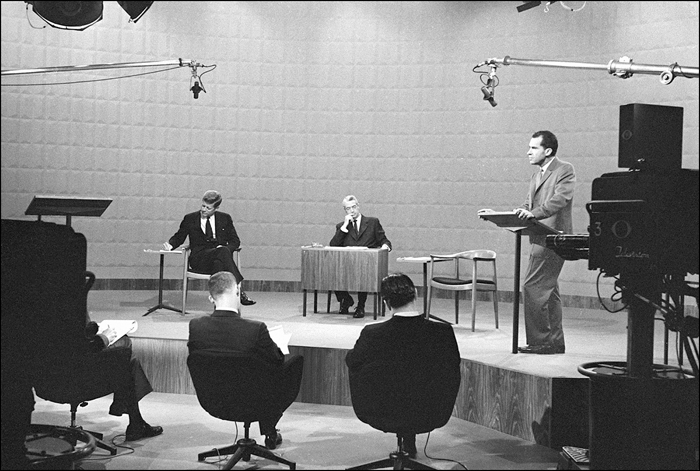

Preparation played a key role in the 1960 U.S. presidential election when the underdog challenger, John F. Kennedy, upset the favorite, sitting Vice President Richard M. Nixon, in that famous first-ever televised debate.

The stark differences in how Kennedy and Nixon prepared for that event were chronicled by Professor Alan Schroeder of the School of Journalism at Northeastern University in his book, Presidential Debates, in which he wrote:

Although both Republicans and Democrats in 1960 compiled massive briefing books—JFK’s people called theirs the “Nixopedia”—only Kennedy bothered to practice for the debate with his advisers...[his] predebate preps consisted of informal drills with aides reading questions off index cards....

According to Nixon campaign manager Bob Finch, “We kept pushing for [Nixon] to have some give-and-take with either somebody from the staff...anything. He hadn’t done anything except to tell me he knew how to debate. He totally refused to prepare.” [9.5]

Kennedy and Nixon also differed in how they prepared to approach the new medium.

The television director of the debate, Don Hewitt (who went on to become the driving force behind CBS’ 60 Minutes), described some of the behind-the-scenes preparation factors in his autobiography Tell Me a Story. Kennedy arrived in Chicago three days before the debate to rehearse and even took some time in the late September sun to burnish the tan he had developed campaigning during the summer. Nixon, who was fighting a viral infection, continued to campaign vigorously right up to the day of debate. He arrived at the WBBM-TV studio in Chicago exhausted and underweight, his clothing hanging loosely over his thin frame.

When Kennedy got to the studio, he accepted a light coat of professional makeup. Nixon’s aides hurriedly applied a slapdash coat of a product called “Lazy Shave” to his characteristically heavy beard. Professional makeup is porous, “Lazy Shave” is not. Under the hot lights of the television studio, Nixon perspired, making him appear nervous. [9.6]

The Kennedy team had surveyed the studio in advance and advised him to wear a dark suit to contrast with the light gray backdrop on the set, a staple in those days of black-and-white television. Nixon wore a light gray suit that translated into the same monochrome value as the background and made him appear washed out (see Figure 9.1).

There was only one clock in the WBBM-TV studio, which was on the wall over Nixon’s left shoulder. Therefore, whenever Nixon spoke, Kennedy could see his opponent and the clock without having to shift his eyes. Alternatively, whenever Kennedy spoke, Nixon had to dart his eyes away from his opponent to track the time.

This being the first televised debate, the candidates were not fully aware of the inner workings of the medium. To create visual variety, television directors alternate images of the person speaking and the person not speaking in what is known as “cut-aways” or “reaction shots.” As a result, when Hewitt showed reaction shots of Kennedy while Nixon was speaking, Kennedy’s eyes barely moved, making him appear alert and focused; when Hewitt showed reaction shots of Nixon while Kennedy was speaking, Nixon’s eyes darted, making him appear nervous and shifty-eyed. Ten years earlier, in a campaign for the senate seat in California, Nixon was labeled “Tricky Dicky” by his opponent. In his first solo run for national office, his furtive eye movements reinforced the label.

In one final touch, during Kennedy’s closing statement, Hewitt inserted another reaction shot of Nixon who nodded in seeming agreement with his opponent!

Nixon had held a slim lead in the public opinion polls right up to the day of the debate. The day after the debate, Sindlinger and Company, a Philadelphia research organization, conducted a telephone poll. Those poll respondents who had watched the event on television thought Kennedy had won, and those who had listened on the radio thought Nixon had won. [9.7]

John F. Kennedy took the lead in the polls and held it until his victory in November.

From that moment on, media consultants became as important as positioning strategists in political campaigns and, from that moment on, preparation became an absolute imperative for debates. Although there were no other presidential debates until 1976, they became set pieces every four years thereafter. In each of those years, each candidate, accompanied by key staff members, ramped up for each debate with the thoroughness of the Allies planning for D-Day.

The teams and the candidates review research, brainstorm, and refine their positions, screen their opponent’s videos, and hold mock debates with carefully chosen stand-ins. Some even have rehearsal studios built to replicate those of the actual venue.

Over the years, each debate provided lessons for subsequent debates. Cumulatively, the candidates and their campaign staffs have compiled long lists of what to do and, more importantly, what not to do. After more than half a century, the accumulated intelligence about televised political debates has become a sophisticated science. Professor Schroeder’s book provides a full chapter with details about how the candidates prepared for their debates:

![]() 1976: Gerald Ford versus Jimmy Carter

1976: Gerald Ford versus Jimmy Carter

![]() 1980: Ronald Reagan versus Jimmy Carter and John Anderson

1980: Ronald Reagan versus Jimmy Carter and John Anderson

![]() 1984: Ronald Reagan versus Walter Mondale

1984: Ronald Reagan versus Walter Mondale

![]() 1988: George H. W. Bush versus Michael Dukakis

1988: George H. W. Bush versus Michael Dukakis

![]() 1992: George H. W. Bush versus Bill Clinton and Ross Perot

1992: George H. W. Bush versus Bill Clinton and Ross Perot

![]() 1996: Bill Clinton versus Bob Dole

1996: Bill Clinton versus Bob Dole

![]() 2000: Al Gore versus George W. Bush

2000: Al Gore versus George W. Bush

The first edition of this book had a detailed analyis of the 2004 debates. For this edition, let’s briefly review that matchup and then move forward to more recent presidential debates.

2004: George W. Bush versus John Kerry

In anticipation of the Bush-Kerry debates, their election teams negotiated for months to establish a set of intricate guidelines. They finally came to terms in a Memorandum of Understanding that ran 32 pages and covered everything from the sublime, the rules of engagement, to the ridiculous, their notepaper, pens, and pencils. Every aspect of the debates was covered in excruciating detail, right down to the exact positions and heights of the podiums.

The lessons of history reverberated behind every stipulation: control of the studio temperature to avoid a repeat of the perspiration that betrayed Richard Nixon; control of the town hall audience microphones to avoid a follow-on question like the one that Marisa Hall asked George H. W. Bush; a set of timing signals installed on each lectern to eliminate the darting eyes that dogged Richard Nixon.

2008: Barack Obama versus John McCain

In an echo of the 1960 presidential election, the 2008 candidates differed markedly in their preparations for their debates: Barack Obama was as diligent as John F. Kennedy and John McCain was as dilatory as Richard Nixon.

Having leapt from obscurity to global fame with a dramatic speech at the Democratic National Convention in support of John Kerry’s candidacy in 2004, Obama deployed his rhetorical skills for his own candidacy in 2008. He spoke on the stump with the passion of his experience as a community organizer, and he prepared for his debates with the thoroughness of his experience as a lecturer on constitutional law. As CNN described it:

Barack Obama is reportedly going to Florida for “debate camp”—traditional preparation that includes a sparring partner playing the role of his Republican opponent.

Having spoken on the floor of the U.S. Senate since 1987, and having campaigned as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 2000 (until George W. Bush defeated him), McCain decided to prepare for his debates, as CNN reported, “on the fly”:

He spent several hours Sunday at his campaign headquarters working with aides, and he spent several hours in a Pennsylvania hotel Monday afternoon doing the same.

He will follow this “squeeze it in” prep schedule Tuesday as he campaigns in Ohio, and Wednesday around meetings with world leaders in New York.

Not until Thursday afternoon and Friday in Mississippi are McCain aides planning to hunker down and devote all the candidate’s time to debate prep. [9.8]

2012: Barack Obama versus Mitt Romney

By the time Barack Obama ran for re-election, he had polished his oratorical skills to a fine sheen at the most prestigious lecterns in the world. Throughout his first term, friends and foes alike agreed that Barack Obama is a commanding speaker. Those same friends and foes expected him to easily outshine former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, whose public persona was most often described as “stiff.”

But in their first debate on October 3 at the University of Denver, Obama threw the media and the political world into a state of shock with a thoroughly lackluster performance. Obama was so out of character, the usually supportive New York Times made its lead story on the morning after the debate, “Romney Wins Debate Praise as Obama Is Faulted as Flat.” [9.9]

The immediate reaction to the debate was a torrent of criticism directed at President Obama, with Republicans, as well as many Democrats, accusing Obama of delivering an uninspired and defensive performance. The Times story went on to report that Andrew Sullivan, a blogger and strong supporter of the President, tweeted that “this is a rolling calamity for Obama.” Sullivan added: “He’s boring, abstract, and less human-seeming than Romney!” [9.10]

And Bill Maher, the liberal comedian who had donated $1 million to a “superPAC” backing Obama, joked: “[I] can’t believe [I]’m saying this, but Obama looks like he DOES need a teleprompter.” [9.11]

Even Obama had to agree. In an interview with radio host Tom Joyner, the President said, “I think it’s fair to say I was just too polite because, you know, it’s hard to sometimes just keep on saying and what you’re saying isn’t true. It gets repetitive.” [9.12]

In search of an explanation for Obama’s tepid showing, veteran political writer Roger Simon wondered, “Perhaps it was mere fatigue that night in Denver. Or overconfidence. Or lack of preparation. Or the altitude.” [9.13]

Most likely, it was lack of preparation. We can’t be certain just how much time and effort any candidate devotes to preparation, but we do know that on the day before that first debate, Obama made a campaign stop at Hoover Dam and, according to the Wall Street Journal:

...complained Monday during a phone call with a campaign volunteer that his aides are “keeping me indoors all the time...making me do my homework.” However, a brown tarp blocking the view of the resort’s basketball court suggests Mr. Obama has been shooting some baskets between sessions. [9.14]

In sharp contrast, in the run up to the second debate, set to take place at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York on October 16, the Wall Street Journal reported that Obama had spent

...three days of prep sessions that began Saturday at a five-star resort in Williamsburg...Outside the sessions, Mr. Obama has spent time walking the grounds of the resort, which is set along the James River, and working out at the gym. [9.15]

Prep sessions are, by nature, highly confidential, but it’s safe to say that one of the topics Obama boned up on was the terrorist attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya on the anniversary of 9/11. In the month leading up to the October debate, each candidate’s campaign team and their many supporters hurled charges and countercharges of responsibility and irresponsibility at the other. So it was incumbent upon each candidate to have a well-supported argument and to be fully prepared to deliver it under the pressure of a live television debate.

Sure enough, about halfway through the debate, Romney challenged Obama on his handling of the Benghazi attack:

There were many days that passed before we knew whether this was a spontaneous demonstration, or actually whether it was a terrorist attack.

And there was no demonstration involved. It was a terrorist attack and it took a long time for that to be told to the American people. Whether there was some misleading, or instead whether we just didn’t know what happened, you have to ask yourself why didn’t we know...

The President replied:

The day after the attack, governor, I stood in the Rose Garden and I told the American people in the world that we are going to find out exactly what happened. That this was an act of terror and I also said that we’re going to hunt down those who committed this crime.

And then a few days later, I was there greeting the caskets coming into Andrews Air Force Base and grieving with the families.

And the suggestion that anybody in my team, whether the Secretary of State, our U.N. Ambassador, anybody on my team would play politics or mislead when we’ve lost four of our own, governor, is offensive. That’s not what we do. That’s not what I do as president, that’s not what I do as Commander in Chief.

The forceful statement was followed by a rapid exchange among the debate moderator, CNN’s Candy Crowley, Romney, and Obama:

CROWLEY: Governor, if you want to...

ROMNEY: Yes, I—I...

CROWLEY: ...quickly to this please.

ROMNEY: I—I think interesting the president just said something which—which is that on the day after the attack he went into the Rose Garden and said that this was an act of terror.

OBAMA: That’s what I said.

ROMNEY: You said in the Rose Garden the day after the attack, it was an act of terror. It was not a spontaneous demonstration, is that what you’re saying?

The governor glowered at the president. Obama stared back.

OBAMA: Please proceed governor.

ROMNEY: I want to make sure we get that for the record because it took the president 14 days before he called the attack in Benghazi an act of terror.

OBAMA: Get the transcript.

CROWLEY: It—it—it—he did in fact, sir. So let me—let me call it an act of terror...

OBAMA: Can you say that a little louder, Candy?

CROWLEY: He—he did call it an act of terror. [9.16]

The CEO of a public company whose revenue has not met expectations must be prepared to provide a detailed response to investors in a quarterly earnings call; the CSO of a pharmaceutical company whose drug has failed clinical trials must be prepared to give an explanation to the Board of Directors; the product manager whose product has missed a shipping date must be prepared to offer an alternative plan for a customer. And so must political candidates be prepared to have a response ready for the worst-case scenario when they meet their opponents.

Obama was ready; Romney was not. In his drive to prove that the President was “misleading,” Romney missed an important fact; Obama, in his drive to prepare for the issue, knew that fact cold.

Preparation counts.

As you’ll see in the next chapter, that pivotal moment, along with Obama’s closing statement in the second debate, were to become the turning point in the campaign.

Lessons Learned

Prepare. Anticipate the worst-case scenario. Make a list of the questions you do not want to hear. Find the Roman Columns in the tough questions as well as the non-challenging ones. Develop your positions on every major issue, especially the negative ones. Gather your supporting evidence. Do your research. Do all of this well in advance of your mission-critical Q&A session!

Verbalize. Speak your words aloud in practice just as you will during your actual Q&A session. Verbalization is the equivalent of spring training in baseball, previews of Broadway shows, Murder Boards for senate confirmation hearings, and most pertinent, the mock rehearsals that precede political debates. The latter examples have even more specificity and urgency for you. Politicians speak far more often than do ordinary citizens, and even more so during their campaigns. By the time they get down the homestretch to the debates, they have spoken their messages countless times.

You do not have that advantage. Organize practice sessions to prepare for your actual Q&A sessions. Enlist your colleagues to fire tough questions at you. Verbalize your Buffers. Verbalize your answers until they are succinct and to the point. Verbalize your Topspin to every answer. Verbalize repeatedly, like a tennis volley.

This is a technique I recommend to all my private clients, and particularly to companies preparing their IPO road shows, the most mission-critical of all business presentations. I urge CEOs and CFOs to volley their responses to their list of tough questions over and over until their returns of serves snap like whips. I urge you to treat every Q&A session as your IPO road show. Snap your whip.

The importance of thorough preparation was first put forth in 55 BC by the great Roman orator, Cicero:

Unless the orator calls in the aid of memory to retain the matter and the words with which thought and study have furnished him, all his other merits, however brilliant, we know will lose their effect. [9.17]