74. Ten Best Practices for the IPO Road Show

If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.

—“New York, New York,” Lyrics by Fred Ebb

In the Introduction, you read that, as the coach of the IPO road shows of nearly 600 companies, I applied the same techniques as I did for hundreds of other companies to develop thousands of presentations to raise private financing, sell products, form partnerships, or gain approval for internal projects.

While very few people get the opportunity to make a presentation that seeks to raise north of 150 million dollars, in the ten best practices for IPO road shows that follow, I’m confident you’ll see aspects that resonate with any presentation—and with the techniques throughout this book. As you read these practices, please relate them to your own presentation circumstances.

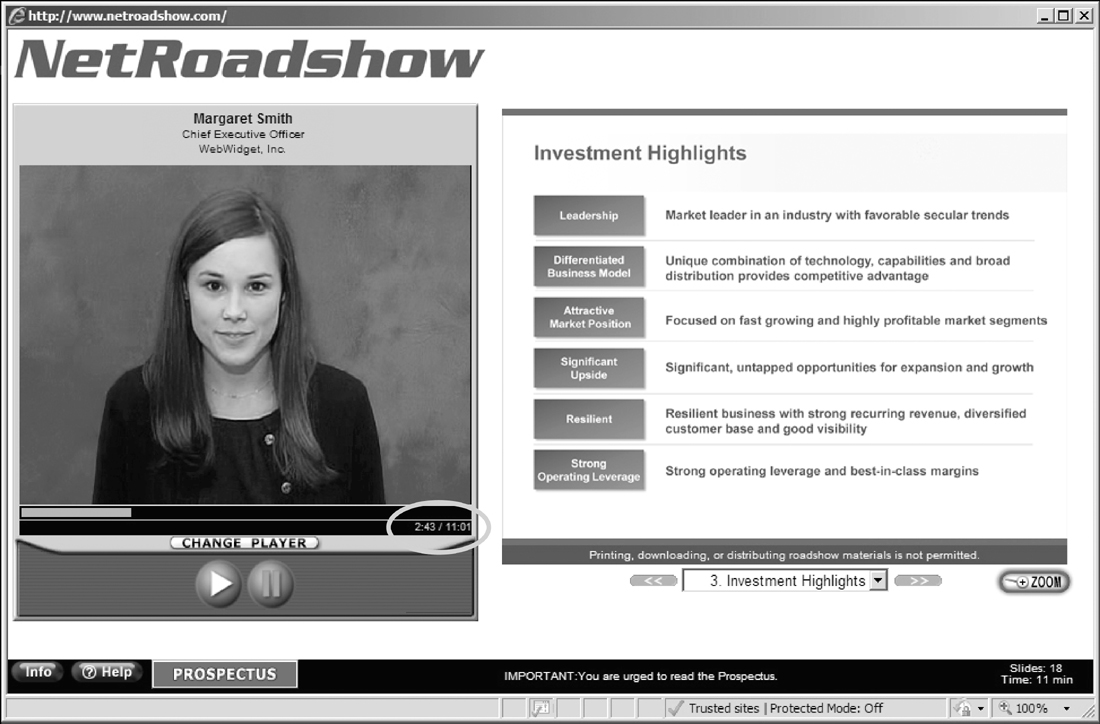

1. The NetRoadshow Factor. In 2005, the Securities and Exchange Commission mandated, in the interest of full disclosure, that companies offering stock for the first time must make their road show presentation available to the public online. Since then, every company makes a video recording of the management team delivering their pitch and posts it on the NetRoadshow/RetailRoadshow site along with the slideshow that accompanies their narrative, as in Figure 74.1.

Figure 74.1. NetRoadshow Web page

Despite this broad access, the company’s senior management team goes on the road for about two weeks, during which they visit potential investors in about a dozen cities across the country for about 30 or 40 meetings a week for a total of 80 or more iterations—just as you read in Chapter 27, “Illusion of the First Time.” The reason for this grueling tour is that no investor will make a decision to buy up to a 10% tranche of the offering (doing the math, that could be a $15 million decision) based on a canned presentation alone. Investors want to meet the executives in person, press the flesh, look them in the eye, and interact with them directly.

Investors have come to rely on the NetRoadshow presentation to get the basics of a company’s story, but they still want to meet the management in person. As a result, many of the meetings are not presentations, but intense Q&A sessions.

But meet they must, and presentation counts.

2. Timing. If you look just below the image of the presenter in Figure 74.1, you’ll see the elapsed as well as the total running time of the presentation. Therefore, every investor who clicks onto the site knows just how long the presentation will last—and the site does not allow fast forward. When you consider that investors who, in the course of their daily jobs, spend most of their time making split-second decisions on trades, and who are likely to be reading and sending emails, instant messages, and tweets while accessing NetRoadshow, you’ll know that this is an audience with very little patience.

Most road shows try to come in under 30 minutes. Pity the poor company that posts a longer running time.

Less is More has never had a better proof point.

3. New audience, new benefits. Until the time of the public offering, most presentations that most companies deliver are to customers. Customers have different benefits than do investors, and so presenters must make that switch. A case study of an IPO from Presenting to Win illustrates this point:

Jim Bixby was the CEO of Brooktree, a company that made and sold custom-designed integrated circuits used by electronics manufacturers. (It was later acquired by Conexant Systems, Inc.) In preparation for Brooktree’s IPO, Jim rehearsed his road show with me. I role played a money manager at Fidelity.

During the product portion of Jim’s presentation, he held up a large, thick manual and said, “This is our product catalog. No other company in the industry has as many products in its catalog as we do.”

Jim set down the catalog and was about to move on to the next topic when I raised my hand and said, “Why should I care?”

With barely a pause, Jim raised the catalog again and replied, “With this depth of product, we protect our revenue stream against cyclical variations.”

That was the right benefit for the right—investor—audience. Tailor every benefit for every audience.

4. Competition. Any company in any market has competitors with whom they are engaged in a mortal struggle—or the market would be worthless. However, investors, seeing the worth in a market, sometimes buy stock in several competing companies. Therefore, when discussing the competitive landscape, lest you make the investor nervous, it would be unwise to bash the competition. Instead, downshift to compare and contrast the entire competitive landscape.

5. Web Animation. The animation feature in PowerPoint, although abused by some presenters, can be an aid to telling a story. At its most basic, animation can be used to present information in incremental, digestible bites. In order to ensure that the NetRoadshow presentation can be accessed by every investor regardless of desktop configuration, the NetRoadshow platform allows for limited animation. As a result, presenters may want to make a separate version of the slideshow using redundant slides to create the additive build effect.

The additive build effect makes images easier for audiences to process.

6. Flow Structure. An IPO road show, just like any presentation, must have a clear and logical story arc. The structure of choice for most road shows is the same—for a simple reason: to parallel the Prospectus. The centerpiece of this carefully wrought document is a “Business” section divided into two major subsections: “Industry Overview,” which is written as an opportunity, and “Company Solution,” which is written as the leverage of the opportunity.

I was privileged to coach the road show of Cisco Systems when they went public in 1990. Here from Presenting to Win is their story arc:

The Cisco team began by describing the shift in computing from mainframes to PCs. They then moved on to delineate the rapid growth of local area networks and wide area networks (LANs and WANs), and recent improvements in technology that brought significant increases in speed, bandwidth, and power. They ended this cluster with a look at the anticipated shift in business from enterprise-centered to remote-based computing. All of those trends, taken together, represented an opportunity.

Next, they talked about how their new device, called a router, could internetwork all networks. They explained how Cisco manufactured the router, how they serviced it, how they sold it through channels and strategic relationships, and where they intended to go with the router in the future. All of these facts, taken together, represented Cisco’s leverage of the opportunity.

In today’s high-speed, PowerPoint-driven world, presenters often hurriedly cobble together a disparate set of slides and proceed to deliver them in a sequence that only they understand. Take the time to create your story with a clear, logical arc that makes it easy for your audience to follow—or they will make it hard for you.

7. Verbalization. In Chapter 46, “Eight Presentations a Day,” you read about the value that Noland Granberry, the CFO of Silicon Image, Inc., experienced from speaking his presentation aloud multiple times. Please note that Mr. Granberry is an American who was speaking in his native language. In today’s globalized world, many speakers must present in a second language. Verbalization is even more helpful to them.

Take the case of a large Israeli technology manufacturing company whose IPO road show I coached. I spent several days working with them at their plant outside Tel Aviv, but before returning to the United States, I urged them to Verbalize on their own. They did so with a vengeance, presenting to several different groups of employees: in the cafeteria, small conference rooms, training classrooms, and large meeting rooms.

When they started their road show, I went to see them present at a luncheon meeting in San Francisco. They had presented in Los Angeles that morning, but due to the usual San Francisco fog, their flight was delayed. You can image the mood in the room among those characteristically impatient investors. However, when the Israeli team arrived, they were so well prepared, they presented with complete cool, calm control. And they were speaking English as a second language! Verbalization works.

8. Team building. The Israeli team above experienced two other benefits from the multiple iterations of their presentation to multiple groups of employees:

• The employees felt involved.

• The employees provided unique insights on the company’s story.

Rehearse your presentations to your colleagues to gain perspective.

9. Assertive Language. In Chapter 11, “Meaningful Words,” you read how the conditional mood, used to avoid forward-looking statements, weakens narrative language. That problem is heightened in IPOs because the senior management team that delivers the road show spends many hours over many months in drafting sessions for the Prospectus. Those sessions are led by attorneys whose customary cautionary views produce a document composed almost exclusively in the conditional mood. That mood spills over into the road show.

Far be it from me to prompt CEOs and CFOs to switch to the declarative mood and risk making those dreaded forward-looking statements. But I do urge them—and you—to replace “We believe...” “We think...” and “We feel... with “We’re confident....”

10. Make direct references to each audience. Here, I reiterate the importance of “the illusion of the first time,” the subject of Chapter 27. I reiterate it because most IPO road show CEOs and CFOs—and most presenters—neglect to do so.

I saved this reiteration for last because, of all the techniques in this book, this one provides the biggest bang for the buck; and yet, in the heat of battle, it is implemented the least.

Use it or lose it.