- Question. A question directed at the members of the audience.

- Factoid. A striking statistic or little-known fact.

- Retrospective/Prospective. A look backward or forward.

- Anecdote. A short human-interest story.

- Quotation. An endorsement about your business from a respected source.

- Aphorism. A familiar saying.

- Analogy. A comparison between two seemingly unrelated items that helps illuminate a complex, arcane, or obscure topic.

One excellent way to open a presentation is with a question directed at the audience. A well-chosen, relevant question evokes an immediate response, involves the audience, breaks down barriers, and gets the audience thinking about how your message applies to them.

Scott Cook, the founding CEO of Intuit Software, used an Opening Gambit Question to powerful effect. Prior to Intuit’s public offering, Scott appeared at the Robertson, Stephens and Company Technology Investment Conference in San Francisco. Here’s how he began his presentation:

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Let me begin today’s presentation with a question. How many of you balance your checkbooks? May I see a show of hands?” Naturally, almost everybody’s hand went up.

“Okay. Now, how many of you like doing it?” Everybody’s hand went down. There were chuckles in the room, and everyone was listening to Scott Cook.

Scott continued, “You’re not alone. Millions of people around the world hate balancing their checkbooks. We at Intuit have developed a simple, easy-to-use, inexpensive new personal finance tool called Quicken that makes balancing checkbooks easy.”

It would have been deadly for Scott to launch into his presentation with a detailed description of Quicken; had he done so, it’s likely that his investment audience would quickly have fallen into the MEGO state. Instead, his Opening Gambit Question captured their interest and got them involved immediately.

But be careful with the call-for-a-show-of-hands question. It can be considered invasive. Many audiences have been there, done that, and won’t appreciate being drawn out that directly. Besides, what if you don’t get the show of hands you expect? Yikes! What do you do next? Your question backfires. It worked for Scott Cook because he was a skilled presenter even before starting Intuit, having been a management consultant at Bain and Company.

An effective variation that avoids these dangers of a direct question is to pose a meaningful and relevant rhetorical question to your audience, and then to promptly provide them with an answer. Scott Cook might have said, “If I were to ask how many of you balance your checkbooks, most of you would probably say ‘Yes.’”

Mike Pope, who started as the CFO of DigitalThink, Inc., a public company (since acquired by Convergys) that provides custom e-learning courseware, succeeded to the role of CEO. One of Mike’s first jobs was to announce a new strategic focus for the company to the employees in an all-hands meeting. He was well aware that the new strategy, which involved belt-tightening, would have an impact on some of the employees’ jobs. He chose an approach that emphasized the greater good for the company.

Here’s how Mike began his presentation: “If I were to ask Fred here to define DigitalThink’s strategic focus, he’d give me one answer. If I were to ask Lisa the same question, I’d get another answer. In fact, I’d probably get as many answers as there are people in the company. You’d all be right. That’s because we’re trying to be all things to all people. That won’t work anymore. I’m here today to define our new strategic focus so that we can all be on the same sheet of music . . . and be successful as a company.”

Mike then proceeded to lay out the new strategy. When he concluded his presentation, the audience erupted in spontaneous applause and continued to buzz with positive feedback afterward. By offering them a plan that could produce better results (a WIIFY for them), Mike had prepared them to accept the company’s new conditions.

The rhetorical question can be an excellent icebreaker, as long as it’s both provocative and relevant to your audience.

An Opening Gambit Factoid is a simple, striking statistic or factual statement: a market growth figure, or a detail about an economic, demographic, or social trend with which your audience may not be familiar. This factoid must be closely related to the main themes of your presentation, and to your Point B. The more unusual, striking, and surprising your factoid, the better.

Adrian Slywotzky is a leading management writer and a managing director of Mercer Management Consulting (now merged with and rebranded Oliver Wyman). Adrian often speaks to groups of big-company executives to explain his views about the sources of business growth of the next decade and the strategies business leaders must use to tap those sources. To capture their attention, Adrian begins his presentations with a slide entitled “The Growth Crisis.” It lists several of America’s biggest, most famous, and most admired companies, from a broad range of industries.

Against this backdrop, Adrian says: “Every investor is looking for companies that can offer consistent double-digit growth in sales and profits. Of all the many great companies listed here, none can offer that kind of growth. Not one! It’s startling, but true. Our research shows that once you subtract growth from company acquisitions and other special circumstances, none of these leading firms has been able to grow at double-digit rates over the past decade.”

By the time Adrian has finished communicating this factoid to his audience (which is made up of executives at companies very much like those listed on the slide), many of them are feeling anxious, but all are ready to listen closely to Adrian’s suggested solutions to the predicament.

Think of this approach as “That was then; this is now.” A retrospective (backward) or prospective (forward) look allows you to grab your audience’s attention by moving them in one direction or another, away from their present, immediate concerns: that urgent message on the Blackberry or I-Phone, the mercurial NASDAQ, or that fight with their significant other.

For example, you could refer to the way things used to be done, the way they are done now, and the way you project their being done in the future. The contrast can highlight the value of your company’s product or service offerings, thereby framing an effective lead-in to your presentation’s main themes and your Point B.

A technology company can quickly capture the evolving power of its solution by showing the speed and capabilities of its products five years ago (a lifetime in the high-tech world), the vastly improved speed and capabilities of today, and the still-greater speed and capabilities of the new line of products that will be going on sale in six months’ time.

The Retrospective/Prospective approach can also be used to land a job. I have been privileged to work with Microsoft for most of my 20 years as a coach, and I am often at the company campus in Redmond, Washington. Shortly after the publication of the first edition of this book, a young man came up to me in the corridor carrying a copy and said, “I used a Retrospective/Prospective Opening Gambit to get my job here.” I smiled and said, “Tell me about it.”

The young man said, “I was in a conference room, being interviewed by several people. Then I stepped up to the front of the room and said, ‘Remember when “Yahoo!” was something you said when you were happy? Remember when a web was something spiders spun? And remember when a net was used to catch fish? Well, that was then, and this is now. Now Yahoo! is a major Internet company, the web connects people and computers, and Microsoft’s .NET Framework connects those people and computers!’”

The interviewers were so impressed with the young man’s story, and that he knew about Microsoft’s technology platform for programming applications, they hired him promptly.

By an Opening Gambit Anecdote, I do not mean a joke. I like a good joke as much as anyone, but my professional advice to you, and to every single person I coach, is never to tell a joke in a presentation. No one can predict its success or failure. Even if it does get a laugh, in most cases, it will distract from rather than enhance your persuasive message.

An anecdote is a very short story, usually one with a human-interest angle. Its effectiveness as an Opening Gambit lies in our natural tendency to be interested in and care about other people. An anecdote creates immediate identity and empathy with your audience. An anecdote is a simple and effective way to make an abstract or potentially boring subject come to life.

Ronald Reagan, “The Great Communicator,” never spoke for more than a couple of minutes without using an anecdote to personalize his subject. He was always ready with a brief tale about the brave soldier, the benevolent nurse, or the dignified grandfather as a way of illustrating his themes. Invariably, the tale would coax an empathic nod or a smile of recognition from his audience.

Newspapers and magazines regularly use anecdotes to capture their readers’ attention. Just look in today’s paper. You’re sure to find at least one example of an Anecdote in the opening paragraph. Every professional writer knows how well it works.

Here, from very different settings, are examples of how the anecdote can be used to launch a powerful business presentation:

In the spring of 1996, I worked with Tim Koogle, then the CEO of Yahoo!, the Internet search engine company, as he and his team, including CFO Gary Valenzeula and founder Jerry Yang, planned their IPO road show. Tim and Gary would be the presenters, while the irrepressible Jerry would come along to answer questions. After considering several possible Opening Gambits, Tim decided to begin his presentation with a personal and true-to-life anecdote keyed to a concern he knew he shared with every member of his audience. His anecdote went something like this:

Hello, ladies and gentlemen. As you can imagine, going public is a very busy time: There are SEC documents to file, meetings with lawyers and auditors, a road show presentation to prepare, and, of course, a company to run. Imagine how I felt last week when I suddenly realized it was April and I hadn’t prepared my tax returns. I had a host of questions about my return, and I hadn’t even had a chance to sit down with my accountant.

Fortunately, I work for Yahoo!. So I logged on, clicked on the Yahoo! home page, clicked on the menu item called Finance, then clicked on the menu item called Taxes . . . and the answers to all my questions were right there.

When you consider that Yahoo! provides this kind of powerful Internet search service for a vast array of subjects, from finance to travel to entertainment to sports to health, and then consider the growing legions of users of the Internet, you’ll see that the advertising revenues Yahoo! can derive from those legions of users represent a very attractive business opportunity. We invite you to join us.

The Yahoo! IPO story has an interesting extra twist that sheds light on some other presentation principles. A key element of the Yahoo! business model was to promote its brand with a youthful, irreverent, and upbeat image, expressed by its name, its advertising, and even by the cartoonish-like letters of its bright yellow and purple logo. In planning the IPO road show, the Yahoo! team and their advisors pondered ways to capture that brash image without alienating staid investors. At one point, they even considered wearing satin team jackets in the company colors for the road show, and distributing bright yellow kazoos emblazoned with the company logo. These plans were abandoned in favor of a short video intended to set the tone at the very beginning of the presentation. Shot in MTV fashion, replete with fast cuts and odd camera angles, the clip featured exuberant youngsters running, jumping, and performing antics while shouting, “Do you Yahoo!?”

By all standards, the video was very well done. And as a television veteran, you might assume that I’d have welcomed the idea of starting a presentation with a video clip. But as I always do when a video is considered, I recommended that it be relegated to second position, after Tim Koogle’s Opening Gambit Anecdote. After all, I reasoned, the primary investment consideration was management, not slick videos. In fact, Tim had been recruited to run the upstart company because he had gravitas. He had served as the president of Intermec Corporation, a division of Litton Industries, and prior to that, had spent eight years at Motorola. Tim’s history of success in these respected, “grown-up” businesses would go a long way toward getting the investment community to take the Yahoo! kids seriously. Why not make management the star?

The investment bankers underwriting Yahoo!’s IPO overruled my recommendation. It was probably one of the few times in history that the advice of a media person was rejected by an investment banker as being too conservative. The video ran first. In the end, it didn’t matter much. Yahoo! was so hot that its bandwagon rolled merrily along, with legions of eager riders clamoring to get onboard.

Three years earlier, however, in a similar situation, my counsel was heeded by another company, Macromedia, which made software authoring tools for multimedia. Macromedia has since been acquired by Adobe Systems, but at the time, they engaged me to coach their IPO road show team. I didn’t get around to starting my program with them until after they had used in-house resources to develop an animated film to open their road show. The film clip was quite impressive. It showed a sparkling, animated, golden M dancing onto the screen, performing spins and leaps to effervescent soundtrack music. Nevertheless, as always, I recommended that the film be relegated to second position, after the CEO’s Opening Gambit.

Then I helped Macromedia CEO Bud Colligan develop the following anecdote:

Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to the Macromedia public offering. Last year, I was king of the hill at Apple Computer. I had a great job that provided me with boundless resources, deep staff, and abundant budgets. Why, you might ask, would I make the leap to this risky startup? The reason is that my job at Apple was to evaluate and develop new technologies. A lot of fascinating new programs and devices came across my desk, but the one that really caught my eye was multimedia.

Now I’m sure that you’ve all heard a lot about multimedia lately. The word seems to be on everybody’s lips. But if you were to ask someone to explain the term, most people would have trouble doing so. So rather than try to define multimedia, let me show you multimedia.

Bud then ran the film clip. Thanks to Bud’s setup with the Opening Gambit Anecdote, the film was much more than a charming bit of fluff. It was also an impressive demonstration of the kind of creativity that Macromedia could make available to millions of customers, and therefore highly relevant to the Macromedia Point B.

Now let’s consider an example from a completely different business setting. Argus Insurance is a Yakima, Washington-based company that sells worksite insurance benefit plans to company employees. These are customized plans that allow each employee to pick the kinds of coverage he or she most needs and wants to pay for, above and beyond the insurance provided by their employer.

Traditionally, Argus agents had simply visited companies, gathered employees in a room, and showed them a generic videotape about their service. The Argus agents then handed out pamphlets and waited to take orders, which were too often few and far between.

When I worked with a group from Argus, I introduced them to the concept of the Opening Gambit. With just a little help, Carol Case, an Argus Insurance agent, came up with the following Opening Gambit based on a real-life scenario:

Last year, one of Argus’ customers had a fire in their home. They think an electrical short might have caused it, but no one really knows. Anyway, the home burned down, destroying almost everything they owned. Talk about a disaster! Not only did they lose their home, they were financially crippled as well.

Our insured, like many people, now realizes he could be just one step away from disaster. Luckily, we at Argus Insurance had a solution. Argus reviewed his previous insurance plan and found gaps in the coverage. We then provided quotes for comprehensive, low-cost insurance that provided coverage not provided by his previous policy.

Any human being can identify with this scenario. Carol is signing up many more Argus customers now than in the past, thanks largely to the power of a compelling Opening Gambit.

Another option is the Opening Gambit Quotation. That doesn’t mean a quotation from William Shakespeare, Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, or even Tom Peters . . . unless one of them said something about your company. But if you can provide an endorsement or positive comment about yourself, your products, or your services from The Wall Street Journal or the industry press, the quotation provides relevant value. An endorsing quotation can capture your audience’s interest and give you credibility at the outset of your presentation.

Please resist the temptation to go to your local bookstore or library and get one of those Ten Million Quotations for All Occasions books. Most often, all those quotations turn out to be inappropriate for any occasion.

Please resist the temptation to get one of those Ten Million Quotations for All Occasions books. Most often, all those quotations turn out to be inappropriate for any occasion.

When DigitalThink went public in 1999, Mike Pope was the CFO. At the time, the Internet was bubbling into high froth, and a host of other companies in the e-learning space were going public, too. Three years later, upon Mike’s succession to CEO, he participated in the Power Presentations program. During the program, Mike smiled knowingly when I introduced the Opening Gambit Quotation option.

Why the smile? Mike explained: “The year we went public, almost every e-learning IPO road show used a quotation from John Chambers [the CEO of Cisco and a kingpin of the Internet]. Chambers said, ‘The next killer application for the Internet is going to be education. Education over the Internet is going to be so big it is going to make email usage look like a rounding error.’” The quote was a relevant, validating, and compelling start for any company in that space.

An aphorism, or a familiar saying, can make for an excellent Opening Gambit. But be sure to select one that relates naturally and credibly to your main theme, and to your Point B.

Here is an example of an Opening Gambit Aphorism: A biotechnology company, being formed by the merger of three smaller companies with related sciences in cancer research, launched their presentation with the following: “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” The original axiom from Euclid, the founder of geometry, is “The whole is equal to the sum of its parts,” but the biotech presenters gave the familiar saying a little twist. In doing so, they instantly identified the synergies that the new company would enjoy by combining competencies and resources.

Here are a few other examples:

- A company that made graphic display screens used “Seeing is believing” to immediately express the clarity and fidelity of their unique products.

- A company with a speech recognition technology used “Easier said than done.”

- A company that played in a niche market between two giant competitors used “Hit ’em where they ain’t.” This aphorism, attributed to oldtime baseball great Wee Willie Keeler, is a pithy way of saying, “You don’t have to be the biggest or the strongest to win in a competition; you can succeed simply by focusing on an area that others are ignoring.”

In each case, the Opening Gambit Aphorism triggered the audience’s attention at the outset, allowing the presenter to move them into the heart of the presentation. Grab and navigate.

The final option, the Opening Gambit Analogy, is one of the most popular and most effective. An analogy is a comparison between two seemingly unrelated items. In the Introduction to this book, I drew an analogy between a massage therapist and an effective presenter. I hope that got your attention.

A well-crafted analogy is an excellent way of explaining anything that is arcane, obscure, or complicated. If your business deals with products, services, or systems that are technologically complex or that require specialized knowledge to understand, look for a simple analogy that can allow audiences to grasp the essence of the story.

The simpler and clearer the analogy, the better. If you were trying to sell investors on a company that had developed improved software for data network management, you might explain your business by using a twist on a familiar comparison: “Think of us as the people who repair the potholes on the information superhighway. We plan to collect a toll from every driver who travels on our turnpike!”

Although the roadway analogy is a common choice for networking stories, I found an unusual variation of it for the IPO road show of a biotechnology company. TheraTech (now Watson Laboratories, Inc. of Utah) had a technology that enabled controlled-release drug delivery through transdermal patches. During the road show preparations, Charles Ebert, TheraTech’s Vice President of Research and Development and a Ph.D. in pharmaceutics, began to discuss the essentials of his core science. As Charles knowledgeably and thoroughly described TheraTech’s matrix systems and permeation enhancers, I asked him to pause and explain those terms. Charles said, “Think of the matrix as a truck, think of the drug as its cargo, think of the skin as a border crossing where the truck has to stop, and think of the permeation enhancer as the motor that lifts the barrier and allows the truck to pass through.”

Science is complex; by comparison, business is relatively simple. Often, it’s difficult to combine the two. While the science behind the sequencing of the human genome is complex, its business potential can be explained through an analogy: “Because our company’s researchers were the first to locate and map the genes that cause several major diseases, we’ll be in a position to require royalty payments from the big pharmaceutical firms working to eliminate those diseases. It’s like owning the copyright on a hit song and collecting a royalty every time it gets played.”

Vince Mendillo was the Director of Worldwide Marketing for Microsoft’s Mobile Devices when he made the opening presentation at the Mobility Developers Conference in London. Microsoft organized the conference for independent software vendors, or ISVs, in Europe. ISVs write the applications that drive thousands of mobile devices as well as countless other software products.

Vince began his presentation with an Opening Gambit Analogy, made even more effective by leading up to it with this gracious greeting:

Good morning! And since I am in Europe, I should add: Bonjour, Buenos dias, and, as an Italian-American, Buon giorno!

I’m also a history buff, and I’ve studied the history of the homeland of my ancestors. For centuries, Italy was divided into many autocratic and warring states. But in 1870, as a result of the valiant efforts of Giuseppe Garibaldi, a guerrilla fighter who became a great general, Italy became a unified nation.

The mobile world today is very much like the Italy of yesterday, divided among autocratic warring factions. Now the battle is over technology, platforms, and systems. You ISVs are suffering from the results of that factionalism. We at Microsoft hear you and understand your confusion. In response, we’ve developed an ecosystem of partners that includes Intel, Texas Instruments, and major carriers, all involved with Microsoft to create an open platform that will enable its members to participate in the deployment of 100 million Microsoft mobile devices. We welcome you here today, and invite you to become part of this ecosystem.

Vince’s Opening Gambit Analogy was gracious, analogous, and unmistakably attention-getting.

You can actually combine some of the preceding options for your Opening Gambit. Remember from Chapter 1, “You and Your Audience,” how Dan Warmenhoven, the CEO of Network Appliance, began his IPO road show? He started with the line “What’s in a name?” (an aphorism: Juliet’s immortal query to her Romeo). Then he asked, “What’s an appliance?” (a rhetorical question, followed by the answer): “A toaster is an appliance.” Then Dan used the toaster as an analogy: “A toaster does one thing and one thing well: It toasts bread.”

With this triple Opening Gambit, Dan surely had his audience’s attention, so he moved on to link the analogy to the rest of his presentation: “Managing data on networks is complicated. It is currently managed by devices that do many things, not all of them well. Our company, Network Appliance, makes a product called a file server. A file server does one thing and does it well: It manages data on networks.” Now Dan was ready to move on to his Point B: “When you think of the explosive growth of data in networks, you can see that our file servers are positioned to be a vital part of that growth, and Network Appliance is positioned to grow as a company. We invite you to join us in that growth.”

To make the opening of your presentation as effective as possible, you need to do more than capture the interest of your audience. The optimal Opening Gambit goes further by linking to your Point B.

In every one of the preceding examples, the presenters continued beyond the Opening Gambit, and then hopped, skipped, and jumped along a path that concluded with Point B. To do the same, you’ll need two additional steppingstones: the Unique Selling Proposition (USP) and the Proof of Concept.

The USP is a succinct summary of your business, the basic premise that describes what you or your company does, makes, or offers. Think of the USP as the “elevator” version of your presentation: how you’d pitch yourself if you stepped into an elevator and suddenly saw that hot prospect you’d been trying to buttonhole. But please, make it a four-story elevator ride, not a 70-story trip!

The USP should be one or, at most, two sentences long. One of the most common complaints about presentations is “I listened to them for 30 minutes, and I still don’t know what they do!” The USP is what they do.

Remember Dan Warmenhoven’s opening: “Our company, Network Appliance, makes a product called a file server. A file server does one thing and does it well: It manages data on networks.” A very clear, concise USP.

Proof of Concept is a single telling point that validates your USP. It gives your business instant credibility. The Proof of Concept is optional. Sometimes you can start with the Opening Gambit, link through the USP, and then go directly to Point B without the extra beat.

It is a valuable beat nonetheless, and when you do choose to include the Proof of Concept, you have a number of options. For example, you can use a significant sales achievement: “We sold 85,000 copies of this software the first day it was available”; a prestigious award: “Business Week picked our product as one of the top 10 of the year”; or an impressive endorsement: “When an IBM vice president tried our product, he told me he’d give anything if only IBM could have invented it.”

Think of your Opening Gambit, your USP, your Proof of Concept, and your Point B as a string of connected dynamic inflection points. Once you’ve segued smoothly through each of them at the start of your presentation, the heart of your argument will be primed for your discussion. You will have grabbed your audience’s attention, and they will be very clear about what you want them to do.

Let’s go back to Scott Cook, the founding CEO of Intuit Software, and the presentation he made at the Robertson, Stephens and Company Technology Investment Conference prior to his public offering. Scott began with two questions: “How many of you balance your checkbooks?” and “How many of you like doing it?”

As the chuckling subsided and all the hands dropped, Scott continued, “You’re not alone. Millions of people around the world hate balancing their checkbooks. We at Intuit have developed a simple, easy-to-use, inexpensive new personal finance tool called Quicken that makes balancing checkbooks easy.” (Intuit’s USP.) Now Scott started to roll: “We’re confident that those millions of people who hate balancing their checkbooks will buy many units of Quicken . . . ” Scott had built up such a head of steam that he skipped past his Proof of Concept, and, without passing Go, went directly to his Point B: “ . . . making Intuit a company you want to watch.”

At that moment in the history of the company, Scott’s sole purpose was to raise awareness among potential investors and investment managers of the upcoming Intuit IPO. Unlike the CEOs of other private companies presenting at the conference, all of whom were seeking financing, Scott was there only to tee up his road show: “ . . . a company you want to watch.” Scott was not there to raise capital. (In fact, at that very conference, Scott declined a handsome investment offer because he had all the working capital he needed from his primary investors, the Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers venture firm.)

As a footnote, Scott is never shy about asking for the order. Of the more than 500 CEOs I’ve coached for IPO road shows, I’ve had to prompt almost all of them to make their call to action. (Remember, one of the Five Cardinal Sins is “no clear point.”) Most CEOs are reluctant to use the “i” word (“invest”). Far be it from me to suggest that they do. Instead, I recommend words like “invite,” “join,” “participate,” and “share.” Only Scott Cook, among those 500, concluded his IPO road show by boldly asking, “Why should you invest in Intuit?” and then providing them with the answers.

Remember from Chapter 4, “Finding Your Flow,” how CEO Jerry Rogers began the Cyrix IPO road show: “Cyrix competes against the established giants Intel and AMD, as well as two other large, well-funded companies.” (Jerry’s Opening Gambit was a factoid . . . in this case, a most striking statement.) “So as a tiny start-up trying to establish itself, I have to respond to some challenging questions from potential new customers about the IBM-compatible microprocessors that Cyrix designs.” (Cyrix’s USP.) “Three questions keep recurring: ‘Will Cyrix microprocessors run all software applications?’ ‘How will Cyrix compete with Intel?’ and ‘Does Cyrix have the financial stability to succeed?’”

Jerry continued, “Cyrix has already begun shipments of the first commercially available 486 microprocessors not produced by Intel.” (Cyrix’s Proof of Concept.) “But those same three questions about compatibility, competition, and finances remain important to potential investors like you. In my presentation today, I’ll provide you with the answers to those questions to demonstrate that Cyrix is indeed a sound investment.” (Cyrix’s Point B.)

Jerry’s answers and his call to action proved to be effective: When Cyrix launched as a public company, their shares were priced at $13, and the first trade was over $19, a significant achievement in 1993.

Now let’s move from CEO Jerry Rogers to Carol Case, the salesperson from Argus Insurance you met earlier in this chapter. Carol began her pitches to her prospective buyers with the scenario about the fire. After the scenario, Carol continued: “Our customer is like many customers who purchase a basic policy not customized to their individual needs. He now realizes that means being just one step away from disaster. Luckily, we at Argus Insurance have a solution. Argus can provide you with a customized, value-added package of insurance that provides for your individual needs to protect you against serious financial loss.” (Argus’ USP.) Carol was already teeing up her Point B, but for good measure, she added her Proof of Concept: “Maybe that’s why Argus is one of the fastest-growing insurance brokers in the state.” Now, she was ready for an even stronger Point B: “I know that you’ll want to take advantage of the opportunity and sign up for this important coverage today.”

When you power-launch your presentation with your Opening Gambit, your USP, your Proof of Concept, and your Point B, your audience will have no doubt about where they’re going. Now it’s time for you to tell them how you intend to navigate them there.

The prior dynamic inflection points will prime your audience, but do you want to now dive directly into the body of your presentation? Do you want to start drilling deeply into the first of the clusters you selected? Not quite yet. I suggest that first you take a moment to give your audience a preview of the outline of your major ideas.

The technique for helping your audience become oriented and track the flow of your ideas is the classic Tell ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em. You can also think of it as the forest view.

In most business presentations, this preview is expressed in the Overview or Agenda slide. In an IPO road show, it’s in the Investment Highlights slide. In either case, it summarizes the chief attractions of a company’s offering. Why not map it to the sequence of the Roman Columns? Why not make it track the entire presentation? In that way, you and your audience can see all the major Roman Columns and the Flow Structure that unifies them. This is a view of both the trees and the forest. Think of it as a final quality check.

But telling your audience what you’re gonna tell ’em has much more to offer than an agenda. You can also extend your narrative string with two more dynamic inflection points: link forward from Point B and forecast the running time of your presentation.

In the Argus Insurance sales pitch, after Carol Case asked for the order with “I know that you’ll want to take advantage of the opportunity and sign up for this important coverage today,” she continued on to her Overview slide with “ . . . so that you can consider signing with Argus . . . ”, and then she ran through the bullets of her Overview slide.

Contrast Carol’s forward link with the far more common approach of no link at all: “Now I’d like to talk about my agenda . . . ”

In the opening of the Intuit IPO road show presentation, after Scott Cook’s call to action with “Why should you invest in Intuit?”, he made a forward link to his Investment Opportunity slide (shown in Figure 5.1) with “These are the reasons to consider Intuit for your portfolio.” Then he ran through the bullets, briefly, adding value to each point.

In doing so, Scott avoided the all-too-common practice of reading the bullets verbatim; a practice that invariably annoys any audience, because they think to themselves: “I’m not a child! I can read it myself!”

When Scott was done with the bullets, he added, “Please consider this the outline for the next 20 minutes of our presentation. Let’s start at the top with the market opportunity,” adding yet another forward link, this time into the heart of his presentation.

Instead of plunging your audience headlong into a dark tunnel, establish the endpoint at the beginning of your presentation; show them the light at the end while they are still at the entrance. By stating how long your presentation will take, you demonstrate that you respect the value of your audience’s time and intend to use it productively. Another aspect of Audience Advocacy.

By providing your audience with a road map and a forecast of the time, you are giving them a plan and a schedule. These four italicized nouns have a least-common-denominator noun: management. Once again, you’re sending the subliminal message of Effective Management.

Of course, just because you’ve told ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em, no one will think of you as an excellent manager. That’s a stretch. But the converse proves the point: If you plunge your audience headlong into that dark tunnel without providing a road map or endpoint, they’ll feel out of control. If instead you show them the light, they’ll sit back, lock into your message, and subconsciously say to themselves, “These people know what they’re doing. They have a plan. They’re well prepared. Let’s listen to what they have to say.”

Telling ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em also provides additional benefits to you, the presenter. When you click on your Overview slide and run through it for your audience, you can mentally check the components of your presentation and remind yourself of the overall flow of ideas. This will make it easier for you to move confidently from point to point as you step through the body of your presentation. Remember how well that worked for Hugh Martin of ONI Systems and his “Top 10 Questions from Institutional Investors”?

Furthermore, it’s quite likely that someday, someone will come up to you five minutes before your presentation and say, “Gee, I’m sorry, but we’re running awfully late. We planned to give you half an hour, but we can only spare eight minutes.”

Panic time? No; simply move to your Overview slide and walk your audience through your key points in the allotted time. After all, since the Overview slide is a miniature view of your entire presentation, you can use it to support an ultra-brief condensation of all your ideas.

That old chestnut Tell ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em has a host of benefits: road map, linkage, forecast, prompt, and short form.

You can now proceed to fulfill your forecast by telling ’em what you promised. That is, move through each of your clusters in greater detail, putting flesh on the sturdy bones of your structure.

Of course, when you’re done with all the clusters, you then tell ’em what you told ’em. In most presentations, this is in the Summary slide; in an IPO road show, it’s in the Investment Highlights slide. In both cases, it’s a mirror of its predecessor from the beginning of the presentation. This mirroring, this linking of the preview and the summary, serves to bookend the presentation. This also creates a thematic resolution that neatly ties together the entire presentation. Express that resolution with a final restatement of your Point B. The last words your audience should hear is your call to action.

An important footnote about your summary: Make it brief! In a book, when only a few pages are left and the reader knows that the end is in sight, the writer quickens the pace of the narrative. So it is with a presentation. When you get to your Summary slide, discuss it succinctly.

You have now effectively grabbed your audience at the beginning, navigated them through all the parts, and deposited them at Point B. Moreover, your whole story has now fulfilled Aristotle’s classical requirements for any story: a strong beginning, a solid middle, and a decisive end.

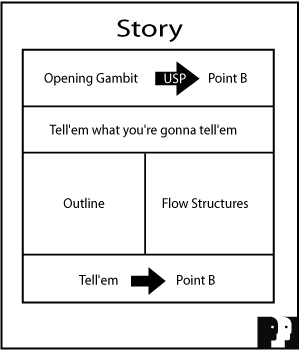

In the Power Presentations programs, we provide a Story Form (see Figure 5.2) that captures all the preceding points. It’s a useful tool for tracking a basic format that will work for any persuasive presentation.

Figure 5.2. The Power Presentations Story Form. (You can download a copy of this form by visiting our website, www.powerltd.com.)

The Opening Gambit, the USP, a forward link to Point B, another forward link to Tell ’em, and one more forward link into the Overview are the first important steps of any presentation. This continuous string creates a dynamic thrust that propels and energizes the balance of your time in front of your audience.

It’s important that you hit these points, and in that order, within the first 90 seconds of your presentation . . . at the maximum. Always remember the importance of the start of your presentation. If you lose your audience within that first 90 seconds, chances are they will be lost forever. Remember, you never get a second chance to make a first impression.

But if you capture your audience’s attention, define your Point B, and establish your credibility in those same 90 seconds, the audience is yours, and they will follow you wherever you want them to go.

Jim Flautt was the Vice President of Marketing at DigitalThink. He participated in the same Power Presentations program in which Mike Pope, the newly ascended CEO, developed a presentation to announce the company’s new strategic focus.

The day after the program, Jim attended a presentation at the alumni association of his graduate business school. He decided to watch from the back of the room, as I do, to observe not only the presenter, but the audience reactions as well. The guest speaker was a respected industry leader and a frequent presenter, but his presentation was, from the outset, an unabated torrent of excessive words and slides. Jim could see that the audience quickly lost interest: MEGO. As he watched the shifting heads and squirming bodies in front of him, Jim smiled knowingly. He understood exactly what had gone wrong.

The next day, Jim, who happens to be an Annapolis graduate and a former naval officer aboard the USS Albany, was scheduled to speak about submarines to his son’s first-grade class at Laurel Elementary School. Jim realized that a roomful of seven-year-olds, who represent the ultimate in short attention spans, would be as challenging as any business audience. So he set about to make use of what he’d learned about making business presentations to prepare for the first-graders.

In the style of Intuit’s Scott Cook, Jim began with a call-for-a-show-of-hands Opening Gambit, a format quite familiar to his young audience. Jim had three questions: “How many of you know what a submarine is?” All the first-graders raised their hands. “How many of you have ever seen a submarine?” Half the first-graders raised their hands. “How many of you have ever seen a submarine fly?” Now all the first-graders smiled, giggled, and gasped. Jim had their attention.

Jim continued on to his Point B: “Well, I’m here today to tell you all about submarines.” Then, to link forward from his Point B, Jim told ’em what he was gonna tell ’em: “ . . . what goes on in a submarine, how to drive a submarine, how to repair a submarine, and some cool things that a submarine does. When I’m done with all of that, about 15 minutes from now . . . ” (Jim’s forecast for time) “ . . . I’ll show you a submarine that flies!” Just for good measure, Jim added a big WIIFY.

This got more smiles, giggles, gasps, and now, delighted cheers from the children. Jim had them and he kept them, with simple slide photographs, in rapt attention for about 15 minutes, until the very end. Then, true to his promise, Jim clicked on his computer and ran a video clip of a U.S. Navy submarine going through an emergency surfacing exercise, leaping out of the roiling ocean looking, for all the world, like a dolphin performing a stunt.

Jim did it all: he grabbed, navigated, and deposited. If it can work with wired seven-year-olds, it can work with occupationally-short-attention-span investors looking to make a return on their investment, with a concerned customer looking to find a product that performs a vital function better than the current solution, or with a stressed manager looking for a strategy to compete more effectively. It can work for you.