Evaluating and Terminating the Project

As the Beagle 2 Mars probe designed jointly by the European Space Agency and British National Space Center headed to the surface of Mars in December 2003, contact was lost and the probe never heard from again (PMI, October 2004). In retrospect, it appears that excessive pressure on time, cost, and weight compromised the mission right from the start. With insufficient public funding, the design team had to spend much of their time raising private funds instead of addressing difficult technical issues. Further, late changes forced the team to reduce the Beagle's weight from 238 pounds to 132 pounds. The three airbags developed to soften the probe's landing impact failed during tests, and a parachute design was installed, but lack of time prevented sufficient testing of it. A review commission recommended that in the future:

![]()

- Requisite financing be available at the outset of a project.

- Formal project reviews be conducted on a regular basis.

- Milestones be established where all stakeholders reconsider the project.

- Expectations of potential failure be included in the funding consideration.

- Robust safety margins be included and funded for uncertainties.

We now come to the final stage in any project—evaluating the result and shutting down the project. As we will see, there are many ways to do both, some relatively formal, some quick and dirty, and some rather casual. We discuss evaluation first, in the generic sense, and then discuss a very specific and often formal type of evaluation known as the project audit. Following this we discuss termination of the project.

8.1 EVALUATION

The term “evaluate” means to set the value of or appraise. A project evaluation appraises the progress and performance relative to the project's initial or revised plan. The evaluation also appraises the project against the goals and objectives set for it during the selection process—amended, of course, by any changes in the goals and objectives made during the project's life. In addition, evaluations are sometimes made relative to other similar projects.

The project evaluation, however, should not be limited simply to an after-the-fact analysis. Rather, it is useful to conduct an evaluation at a number of crucial points during the project life cycle. Because the primary purpose of a project evaluation is to give feedback to senior management for decision and control purposes, it is important for the evaluation to have credibility in the eyes of both senior management and the project team. The control purpose of evaluation is meant to improve the process of carrying out projects. The decision purpose is intended to improve the selection process. Thus an evaluation should be as carefully planned and executed as the project itself.

![]()

The use of postproject evaluation is to help the organization improve its project-management skills on future projects. PMBOK refers to this as “lessons learned,” a topic PMBOK covers in Chapter 8 on Quality. This means that considerable attention must be given to managing the process of project management. This is best accomplished and most effective if there is already a project-management guide or manual detailing standardized project-management practices for the organization. Such manuals commonly cover best practices for planning, monitoring, and controlling projects and may include advice on both selecting and terminating projects. An example of such a manual was that developed by Johnson Controls, described in Chapter 7, where internal benchmarking of their most successful project managers identified four sets of detailed project management procedures. These procedures are updated with each new project experience so that the learning that has occurred is captured and made available for future projects.

Evaluation Criteria

There are many different measures that may be applied in a project evaluation. As indicated, senior management may have particular areas they want evaluated for future planning and decisions, and these should be indicated in the charge to the evaluation committee. Beyond that, the original criteria for selecting and funding the project should be considered—for example, profitability, acquiring new competencies for the organization, or getting a foothold in a new market segment. Any special reasons for selection should also play a role. Was this project someone's sacred cow? Did a scoring model identify particularly important quantitative or qualitative reasons to select this project? Was the project a competitive necessity? How the project is progressing on such criteria should be an important part of the evaluation as well.

Certainly, one of the major evaluation criteria would be the project's apparent “success” to date. One study (Shenhar, Levy, and Dvir, 1997) identified four important dimensions of project success. The first dimension is simply the project's efficiency in meeting the budget and schedule. Of course, efficiency does not necessarily translate into performance, or effectiveness, so the second (and most complex) dimension is customer impact/satisfaction. This dimension includes not only meeting the formal technical and operational specifications of the project but also the less tangible aspects of fulfilling the customer's needs, whether the customer actually uses the project results—that perennial challenge of customer “satisfaction.”

The third dimension is business/direct success meaning, for external projects, factors such as the level of commercial success and market share and for internal projects, the achievement of the project's goals such as improved yields or reduced throughput time. The final dimension, more difficult to assess, is future potential which includes establishing a presence in a new market, developing a new technology, and such.

Table 8-1 Items to Consider for Project Evaluation Report Recommendations

|

The criteria noted above are usually sufficient for purely routine projects, e.g., maintenance projects. For nonroutine projects, however, two other criteria should also be considered: the project's contribution to the organization's unstated goals and objectives, and the project's contributions to the objectives of project team members. To recognize the project's contributions, all facets of the project must be considered in order to identify and understand the project's strengths and weaknesses. The evaluation report should include the findings regarding these two criteria, as well as some recommendations concerning the items in Table 8-1.

Measurement

Measuring the project's performance against a planned budget and schedule is relatively straightforward, and it is not too difficult to determine if individual milestones have been reached. As we have noted several times, there are complications regarding measurement of actual expenditures and earned values, as well as with reporting on difficult technical issues that may have been deferred while progress was being made along other fronts.

If the project selection process focuses on profits, the evaluation usually includes determination of profits and costs and often assigns these among the several groups working on the project. Conflict typically results. Each group wants credit for revenues. Each group wants costs assigned elsewhere. Although there are no “theoretically correct” solutions to this problem, there are politically acceptable solutions. As with budget and schedule, these are most easily addressed if they have been anticipated and decided when the project was initiated rather than at the end. If allocations are made by a predetermined formula, major conflicts tend to be avoided—or at least lessened.

When a multivariate model (e.g., a scoring model, such as Table D in the scoring model example in Chapter 1) has been used for project selection, measurements may raise more difficult problems. Some measures may be objective and easily measured. Others, however, are typically subjective and may require careful, standardized measurement techniques to attain reliable and valid evaluation results. Interview and questionnaire methods for gathering data must be carefully constructed and executed if their results are to be taken seriously.

A project evaluation is an appraisal for use by top management. Its criteria should include the needs of management; the organization's stated and unstated goals; the original selection basis for the project; and its success to date in terms of its efficiency, customer impact/satisfaction, business success, and future potential. Measuring the project's success on budget, schedule, and scope is easier than measuring revenues or qualitative, subjective factors. Establishing the measures at project formation is helpful, as well as using carefully standardized measurement techniques for the subjective factors.

8.2 PROJECT AUDITING

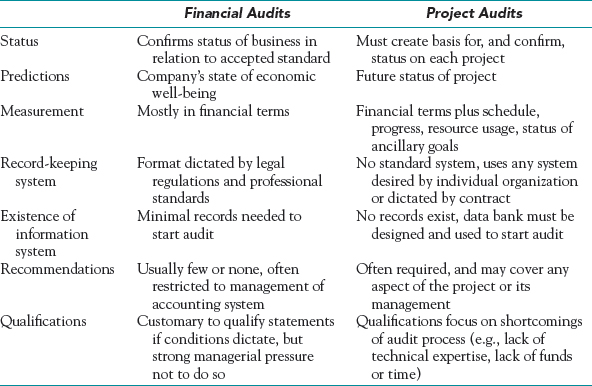

A very special type of evaluation is the formal audit. The project audit is a thorough examination of the management of a project, its methodology and procedures, its records, properties, inventories, budgets, expenditures, progress, and so on. The project audit is not a financial audit, but is far broader in scope and may deal with the whole or any part of the project. For a comparison of the two, refer to Table 8-2. It can also be very flexible, and can focus on any issues of interest to senior management. The project audit is also broader than the traditional management audit that focuses its attention on the organization's management systems and operation. Next we discuss the audit process itself and its result, the audit report.

The Audit Process

![]()

The timing of the audit depends on the purpose of the audit, as shown in Table 8-3. Because early problem identification leads to easier solutions, it is often helpful to have an audit early in the project's life. Such audits are usually focused on technical issues. Later audits tend to focus more on budget and schedule because most of the technical issues are resolved by this time. Thus, these later audits are typically of less value to the project team and of more interest to general management. An obvious case here is the postproject audit, often contractually required by the customer as well as a common ingredient in the Final Project Report.

While audits can be performed at any level of depth, three levels are common. The first is the general audit, usually constrained by time and cost and limited to a brief investigation of project essentials. The second is the detailed audit, often initiated if the general audit finds something that needs further investigation. The third is the technical audit, usually performed by a person or team with special technical skills.

Table 8-2 Comparison of Financial Audits with Project Audits

Table 8-3 Timing and Value of Project Audits

| Project State | Value |

| Initiation | Very useful, significant value of audit takes place early—prior to 25 percent completion of initial planning stage |

| Feasibility study | Very useful, particularly the technical audit |

| Preliminary plan/schedule budget | Very useful, particularly for setting measurement standards to ensure conformance with standards |

| Master schedule | Less useful, plan frozen, flexibility of team limited |

| Evaluation of data by project team | Marginally useful, team defensive about findings |

| Implementation | More or less useful depending on importance of project methodology to successful implementation |

| Post-project | More or less useful depending on applicability of findings to future projects |

Typical steps in a project audit are:

- Familiarize the audit team with the requirements of the project, including its basis for selection and any special charges by upper management.

- Audit the project on-site.

- Write up the audit report in the required format (discussed in the next subsection).

- Distribute the report.

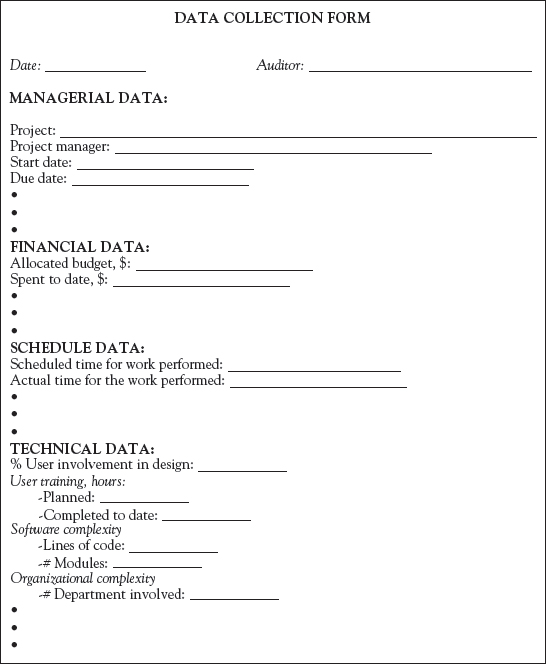

Collection of the necessary data can be expedited by developing forms and procedures ahead of time to gather the required data, such as that inducted by Figure 8-1. To be effective, the audit team must have free access to all information relevant to the project. Most of the information will come from the project team's records or from various departments such as accounting, human resources, and purchasing. Other valuable information will come from documents that predate the project such as the Request for Proposal (RFP), minutes of the project selection committee, and minutes of senior management committees that initiated the project.

Special attention needs to be given to the behavioral aspects of the audit. While the audit team must have free access to anyone with knowledge of the project, except the customer, the audit team's primary source of information should be the project team—but project team members rarely trust auditors. Even if the auditor is a member of the project team, his or her motives will be distrusted and thus the information the auditor requires will be difficult to obtain. Worry about the outcome of the audit produces self-protective activity, which also distracts the project team from activity devoted to the project. Audits are always distracting and uncomfortable to those being audited, much like having a police car in one's rear view mirror while trying to drive.

Trust-building is a slow and delicate process that can be easily stymied. The audit team needs to understand the politics of the project team, the interpersonal relationships of the team members, and must deal with this confidential knowledge respectfully. Regardless, the audit team will undoubtedly encounter political opposition during its work, either to rebuff the team's investigation or to co-opt them. As much as possible, the audit team should attempt to remain neutral and not become involved. If information is given to the audit team in confidence, discreet attempts should be made to confirm such information through nonconfidential sources. If it cannot be so confirmed, it should not be used. The audit team must beware of becoming a conduit for unverifiable sources of criticism of the project. As in all matters pertaining to projects, the project team and audit team must be honest.

Figure 8-1 Form to audit a software installation project.

There are other rules the audit team should follow as well. First, project personnel should always be made aware of the in-progress audit. Care must be taken to avoid misunderstandings between the audit team members and project personnel. Critical comments should always be avoided. This is especially true of on-the-spot, offhand opinions and remarks. No judgmental comment should be made in any circumstance that does not represent the consensus opinion of the audit team, and even consensus judgments should be avoided except in official hearings or reports.

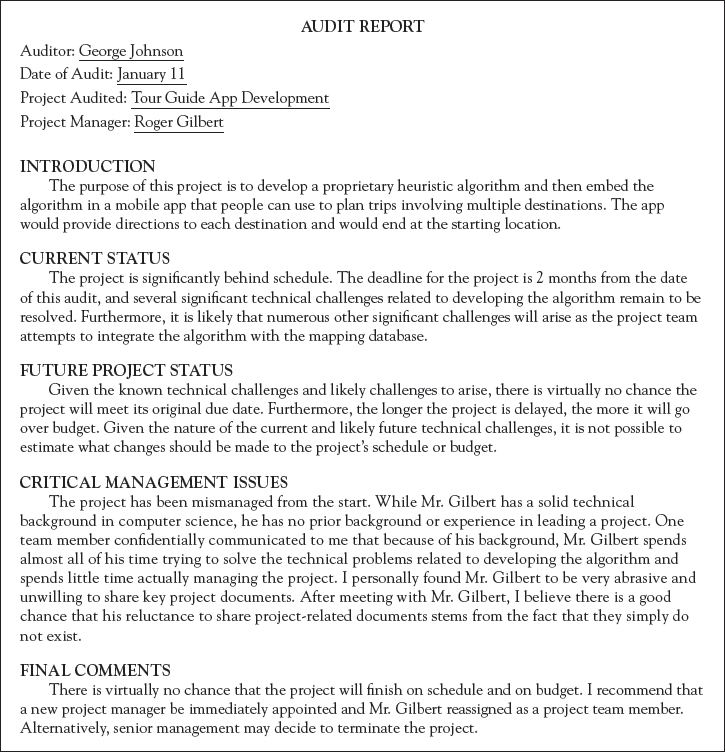

The Audit Report

If the audit is to be taken seriously, all the information must be credibly presented. The data should be carefully checked, and all calculations verified. Deciding what to include and what to exclude is also important. The audit report should be written with a “constructive” tone or project morale may suffer to the point of endangering the project. Bear in mind, however, that constructive criticism never feels that constructive to the criticizee. An example audit report is shown in Figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2 Software installation audit report.

The report information should be arranged so as to facilitate the comparison between planned and actual results. Significant deviations should be highlighted and explained in a set of footnotes or comments. This eases the reader's work and tends to keep questions focused on important issues rather than trivia. Negative comments about individuals or groups associated with the project should be avoided. The report should be written in a clear, professional, unemotional style and its content restricted to information and issues relevant to the project.

At a minimum, the following information should be contained in the report.

- Introduction: A brief description of the project that includes the project's direct goals and objectives.

- Current status: This compares the work actually completed to the project plan along several measures of performance. The actual direct charges made to the project should be compared to the planned budget. If total costs must be reported, including allocated overhead charges, total costs should be presented in addition to the direct charges, not in place of them. The completed portions of the project, especially planned events and milestones, should be clearly noted. The percent completion of unfinished tasks should also be noted if estimates are available. A comparison of work completed with resources expended should be offered—for example, using MSP earned value reports. The need here is for information that can help pinpoint specific problems. Based on this information, projections can be made concerning the timing and amounts of remaining expenditures required for success. Finally, if there are detailed quality specifications for the project, a full review of quality control procedures and the results of quality tests conducted to date must be reported.

- Future project status: The auditor's conclusions regarding project progress and recommendations for changes in technical approach, schedule, or budget should be made in this section. It is not appropriate, however, to try to rewrite the project proposal. The audit report should consider only work that has already been completed or is well under way; no assumptions should be made about technical problems under investigation at the time of the audit.

- Critical management issues: Any issues that the auditor feels senior management should monitor should be identified here. The relationship between these issues and the project objectives should be briefly described.

- Risk analysis and risk management: This section addresses the potential for project failure or monetary loss. The major risks associated with the project and their projected impact on project schedule/cost/performance should be identified. If alternative courses of action exist that may significantly change future risks, they should be noted at this point.

- Final comments: This section contains caveats, assumptions, limitations, and information applicable to other projects. Any assumptions or limitations that affect the data, accuracy, or validity of the audit report should be noted here. In addition, lessons learned from this audit that may apply to other projects in the organization should also be reported.

The project audit is a thorough examination of the entire project at any level of depth. Early audits tend to focus on more technical aspects of the project while later audits focus on schedule and cost. The audit team must have full access to project data and staff familiar with the project, including the project team. Working with the project team is a delicate behavioral process. The final audit report should be written with a professional and constructive tone and should include the following sections: introduction, current status, future status, critical management issues, risk analysis and risk management, plus final comments.

![]()

8.3 PROJECT TERMINATION

![]()

Eventually the project is terminated, either quickly or slowly, but the manner in which it is closed out will have a major impact on the quality of life in the organization. PMBOK refers to this as “project closure” which is covered in PMBOK's Chapter 4 on Integration. Occasionally, the way project termination is managed can have an impact on the success of the project. Invariably, however, it has a major effect on the residual attitudes toward the project held by senior management, the client, the project team, and even others in the organization. It also has a major effect on the organization's successful use of projects in the future.

In some project-organized industries (e.g., construction or software development), project termination is a less serious problem because the teams often remain relatively intact, moving on to the next project. In other industries, however, the termination of a project, particularly a long and difficult one, is akin to the breakup of a family and may well be stressful, even to the point of grieving. Therefore, the skill and management of the termination process—a project in itself—can have a major impact on the working environment of the larger organization.

When to Terminate a Project

If one adopts the position that sunk costs are irrelevant to current investment decisions, a primary criterion for project continuance or termination should be whether or not the organization is willing to invest the time and cost required to complete the project, given its current status and expected outcome. Although this criterion can be applied to any project, not everyone agrees that sunk costs are irrelevant, nor does everyone agree that this is a primary criterion. The criteria commonly applied for deciding whether to terminate a project fall into two general cat egories: (1) the degree to which the project has met its goals and objectives, and (2) the degree to which the project qualifies against a set of factors generally associated with success or failure. Table 8-4 identifies the most important factors in terminating R&D projects at 36 different companies.

Table 8-4 Rank-Ordered Factors Considered in Terminating R&D Projects

| Factors | No. of Companies Reporting the Factor as Being Important |

| Technical | |

| Low probability of achieving technical objectives or commercializing results | 34 |

| Technical or manufacturing problems cannot be solved with available R&D skills | 11 |

| Higher priority of other projects requiring R&D labor or funds | 10 |

| Economic | |

| Low profitability or return on investment | 23 |

| Too costly to develop as individual product | 18 |

| Market | |

| Low market potential | 16 |

| Change in competitive factors or market needs | 10 |

| Others | |

| Too long a time required to achieve commercial results | 6 |

| Negative effects on other projects or products | 3 |

| Patent problems | 1 |

| Source: Dean, 1968. | |

In terms of the first category, if a project has met its goals, the time has come to shut it down. The most important reason for the early termination of a project is the likelihood it will be a technical or commercial failure (Baker et al., 1983). The factors associated with project failure, however, vary for different industries, different project types (e.g., R&D versus construction), and different definitions of failure (Pinto and Mantel, 1990).

As we have already noted, there appear to be four generic factors associated with project success (Shenhar, Levy, and Dvir, 1997): efficiency of project execution, customer satisfaction and use, impact on the firm conducting the project, and contribution to the project firm's future. Success on these dimensions appears to be directly related to the effectiveness of the project's management (Ingram, 1994). There also appear to be four fundamental reasons for project failure: (1) a project was not required for this task in the first place; (2) insufficient support from senior management (especially for unanticipated resources); (3) naming the wrong project manager (often a person with excellent technical skills but weak managerial skills); and (4) poor up-front planning.

Wheatley (2009) takes a broader view of the termination problem. To decide which projects should be continued and which should be dropped, he suggests that the decision makers answer five questions: (1) Which projects have a legal or strategic imperative? (2) Which projects are luxuries? (3) Which projects are likely to drive future revenues and growth? (4) Which projects best match our skill sets and strengths, allowing us to deliver successfully? and, (5) What are the potential risks to the business if we do not service the demands for the project's deliverables? He also suggests taking any pressing current requirements into consideration. For example, if lowering costs to reduce cash flows has suddenly become more important than some longer-run strategic goals, other projects may now take priority over more strategically focused projects.

![]()

Types of Project Termination

There are several fundamentally different ways to close out a project: extinction, addition, integration, and starvation. Project extinction occurs when the project activity suddenly stops, although there is still property, equipment, materials, and personnel to disburse or reassign. The project was terminated either because it was successfully completed or because the expectation of failure was high. Successful projects are completed and delivered to the client. Failures occur when the project no longer meets cost/benefit criteria, or when its goals have been achieved by another project, often in another firm. An example of the former cause of failure is the cancellation of the superconducting super collider (SSC). The SSC project's tremendous costs relative to the lack of clear benefits doomed the project, and it was cancelled during President Clinton's term in office. Other examples of projects facing extinction are when a project's process yield may have been too low, or a drug failed its efficacy tests, or other firms have discovered better alternatives.

One special type of termination that should be noted is termination by “murder,” characterized by its unexpected suddenness, and initiated by events such as the forced retirement of the project's champion or the merger of the firm conducting the project with another firm.

Termination-by-addition occurs when an “in-house” project is successfully completed, and institutionalized as a new, formal part of the organization. This may take the form of an added department, division, subsidiary, or other such organizational entity, depending on the magnitude and importance of the project. 3M Corporation often uses this technique to reward successful innovation projects, such as the invention of Post-It Notes®, and Nucor uses its own construction management teams to staff new steel minimills.

Sometimes, project team members become the managers of the new entity, though some team members may request a transfer to new projects within the organization—project life is exciting. Although the new entity will often have a “protected species” status for the first year or so of its life, it eventually has to learn to live with the same burden of overhead charges, policies, procedures, and bureaucracy that the rest of the organization enjoys. Exceptional project status does not carry over to permanent entities. This shift may be a difficult one for the project team to make.

Termination-by-integration With termination-by-addition, the project property often is simply transferred to an existing or newly created organizational entity. With termination-by-integration, the output of the project becomes a standard part of the operating systems of the sponsoring firm, or the client. The new software becomes the standard, and the new machine becomes a normal part of the production line. Project property, equipment, material, personnel, and even functions are distributed among the existing elements of the parent or client organization. Whether the personnel return to their functional homes in the organization or become a part of the integrated system, all the following functions of the project need consideration in the transition from project to integrated operations: human resources, manufacturing, accounting/finance, engineering, information systems/software, marketing, purchasing, distribution, legal, and so on.

Termination-by-starvation often occurs when it is impolitic to terminate a project but its budget can be squeezed, as budgets always are, until it is a project in name only. The project may have been suggested by a special client, or a senior executive (e.g., a sacred cow), or perhaps terminating the project would be an embarrassing acknowledgment of managerial failure. Occasionally a few project personnel members remain assigned to such a project along with a clerk whose duty it is to issue a “no-progress” report once each quarter. It is considered bad manners for anyone to inquire about such projects.

The Termination Process

As usual, the following process and advice may be ignored in the case of small, routine projects. For all major and nonroutine projects, however, it is best for a broadly based committee of reasonably senior executives to make the termination decision in order to diffuse and withstand the political pressures that often accompany such decisions. In general, projects do not take kindly to being shut down. To the extent possible, it is best to detail the criteria used and explain the rationale for the committee's decision, but do not expect sweet reason to quell opposition or to stifle the cries of pain. Again, the PM will need the power of persuasion. In any case, shutting down an ongoing project is not a mechanistic process and should not be treated as such. There are times when hunches and beliefs about the project's ultimate outcomes should be followed. The termination committee that treats the decision as mechanistic is sure to make some costly errors.

The activities required to ensure a smooth and successful project termination will have, we hope, been included in the initial project plan. The termination process will have much better results for all concerned if it is planned and managed with care—even treating it as a project in itself, as illustrated in Figure 8-3. Usually, the project manager is asked to close out the project but this can raise a variety of problems because the PM is not a disinterested bystander in the project. We believe it is better to appoint a specialist in the process, a termination manager (project undertaker), to complete the long and involved process of shutting down (interring) a project, preferably someone with some experience in terminating projects. The primary duties of the termination manager are given in Table 8-5.

Many of these tasks will be handled, or at least initiated, by the project manager. Some will have been provided for in the project proposal or contract. One of the more difficult jobs is the reassignment of project personnel. In a functional organization, it usually entails a simple transfer back to duty in the individual's parent department; but at those times when a large project is shut down, many team members may be laid off. In a pure project organization there may be more projects to which project personnel can be transferred but no “holding area” such as a home functional department. As a result, layoffs are more common. The matrix organization, having both aspects, may be the least problematic in terms of personnel reassignments.

Figure 8-3 A termination project.

The prevalence of corporate mergers in recent years has exacerbated personnel displacement problems. It is expected that the termination manager and the organization's Human Resources department will aid loyal project workers in finding new employment. This is not merely an act of charity. It may prevent the tendency of some team members to seek employment on their own and leave a project early, which can compromise the successful completion of the project. If such people are unsuccessful in finding new jobs, they may drag out the final tasks to give themselves more time—also detrimental to the project. The PM needs to make it clear that midproject resignations as well as tenure-for-life are both unacceptable. Facing the termination decision in a timely and straightforward manner will pay dividends to the PM, as well as the termination manager, in a smooth project transition.

Clearly, the termination process can be handled well or poorly. An example of the former is Nucor's termination-by-addition strategy where the termination of its Crawfordsville, Indiana, steel plant construction project was planned in detail months ahead of time (Kimball, 1988). An example of poor termination is that which resulted when Atlantic States Chemical Laboratories suddenly saw its contract with Ortec canceled, throwing the project, and its close-out, into disarray (Meredith, undated).

Table 8-5 Main Duties of the Termination Manager

|

The Project Final Report

The project final report is not another evaluation, though the audits and evaluations have a role in it. With the exception of routine projects where a simple “We did it. No problems” is sufficient, the project final report is a history of the project. It is a chronicle, typically written by the PM, of what went right and what went wrong, who served the project in what capacity, what was done, how it was managed, and the lessons learned. The report should also indicate where the source materials can be found—the project plan and all of its many parts; charter, budget, schedule, earned value charts, audit reports, scope-change documents, resource allocations, all updates of any of the above documents, and so on. It is all too easy to ignore these left-overs from yesterday's project, but it is most important not to do so. The PMI refers to these as the organization's assets, and the Project Report is a critical part of them. We think of them as the experiences all managers should learn by—but so often do not.

How the report is written, and in what style, is a matter of taste and preference. In any case, the following items should be addressed.

- Project performance—perhaps the most important information is what the project attempted to achieve, what it did achieve, and the reasons for the resulting performance. Since this is not a formal evaluation of the project, these items can be the PM's personal opinion on the matter. The lessons learned in the project should also be included here.

- Administrative performance—administrative practices that worked particularly well, or poorly, should be identified and the reasons given. If some modification to administrative practices would help future projects, this should be noted and explained.

- Organizational structure—projects may have different structures, and the way the project is organized may either aid or hinder the project. Modifications that would help future projects should be identified.

- Project teamwork—a confidential section of the final report should identify team members who worked particularly well, and possibly those who worked poorly with others. The PM may also recommend that individuals or groups who were particularly effective when operating as a team be kept together on future assignments.

- Project management techniques—project success is so dependent on the skill and techniques for forecasting, planning, budgeting, scheduling, resource allocation, control, risk management, and so on that procedures that worked well or badly should be noted and commented upon. Recommendations for improvements in future projects should be made and explained.

The fundamental purpose of the final report is to improve future projects. Thus, recommendations for improvements are especially appropriate and valued by the organization. Of course, none of the recommendations for improvement of future projects will be of any help whatsoever if the recommendations are not circulated among other project managers as well as the appropriate senior managers. The PM should follow up on any recommendations made to make sure that they are accepted and installed, or rejected for cause.

Since most of the information and recollections come from the PM, it is suggested that the PM keep a project “diary.” This is not an official project document but an informal collection of thoughts, reflections, and commentaries on project happenings. Not only will the diary help the PM construct the final report, but also it can be a superior source of wisdom for new, aspiring project managers. Above all, it keeps good ideas from getting lost amid the welter of project activities and crises.

Projects are usually terminated either based on (1) the degree to which they are meeting their goals or (2) the degree to which they qualify on factors shown to be linked to success or failure in other projects. The most common reason for early termination is the probability of a technical or commercial failure. The four types of project termination are extinction, addition, integration, and starvation. The termination decision should be decided by a management committee, run by a termination manager, and executed as a project in itself. Placing the project team members in new assignments is a particularly important aspect of termination. The PM should prepare a project final report that makes recommendations for improving the organization's future project-management practices.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- If the actual termination of a project is a project in itself, how is it different from other projects?

- What are some reasons that a failing project might still not be terminated?

- What might make a project unsuccessful during the termination process?

- Who would make the best auditors: outside unbiased auditors or inside auditors who are more familiar with the organization, its procedures, and the project? Why?

- Under what circumstances would you change your answer to the previous question?

- Would frequent brief evaluations be best, or would less frequent major evaluations be preferred?

- Should the results of an evaluation or audit be shared with the project team?

- What are the major purposes served by an after-the-fact project evaluation?

- Under what circumstances is a detailed audit apt to be useful?

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

10. How should an audit team handle an audit where it is explicitly restricted from accessing certain materials and/or personnel?

11. What might be some characteristics of a good termination manager?

12. How should a committee decide which termination method to use?

13. What steps might be taken to reduce the anxiety of project team members facing an audit?

14. What are the dangers in evaluating a project based on the reason(s) it was selected (such as its being a competitive necessity), rather than the goals and objectives in the project proposal or contract?

15. It is frequently suggested that items that will become potential problems later in the project life be decided up front, such as how to allocate revenues or dispose of project assets. How can this wisdom be used for project problems that cannot be foreseen?

16. Can you think of any acceptable ways of assigning credit for profits (or responsibility for costs) resulting from a project on which several departments worked?

17. How might an audit team deal with an attempt to co-opt the team?

17. In Section 8.2, subsection The Audit Report, six elements are listed that should be included in every audit report. For each element, explain why its inclusion is important.

19. Referring to the “Evaluation Criteria” subsection of Section 8.1, how do you reconcile the difference between the goals and objectives of the project as given to the project manager in Chapter 1 and these criteria by which she or he is now judged?

INCIDENTS FOR DISCUSSION

General Construction Company

General Construction Company has a contract to build three lower-income apartment buildings for the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico. During construction of the first building, the Project Manager formed an auditing team to audit the construction process for each building. He asked the team to develop a list of minimum requirements for the projects and use this as a baseline in the audit. While reviewing the contract documents, one of the audit team members found a discrepancy between the contract minimum requirements and the City's minimum requirements. Based on his findings, he has told the project manager that he has decided to contact the city administrator and discuss the problem.

Question: If you were the project manager, how would you handle this situation? How can a customer be assured of satisfactory project completion?

Lexi Electronics

Lexi Electronics is nearing completion of a 2-year project to develop and produce a new digital phone. The phone is no bigger than a Popsicle stick but has all the features of a standard digital cellular phone. The assembly line and all the production facilities will be completed in 5 months. The first units will be produced in 8 months. The plant manager believes it is time to begin winding down the project. He has three methods in mind for terminating the project: extinction, addition, and integration. He is not sure which method is best.

Question: Which of the three methods would you recommend, and why?

The shocking Machine

Lithotropic Corporation is the manufacturer of machinery for pulverizing kidney stones with shock waves. They have just completed a new machine. The new machine performs at a medically acceptable level, but it does not precisely meet the specific performance standards that were set for the project. The hospital that contracted for the purchase of the machinery is threatening to sue for failure to deliver to the project specifications. The hospital has contacted Tom Lament, the corporate attorney for Lithotropic.

Question: What do you suggest Mr. Lament do, if anything, to begin his preparation for defending or settling this potential lawsuit?

![]()

St. Dismas Assisted Living Facility Case—6

It was a beautiful day in mid-May 2001. The St. Dismas hospital Assisted Living Facility project was nearing completion. As usual, the construction project manager, Kyle Nanno, was thinking about the construction project's schedule. It seemed to him that work on finishing the interior of the building was slowing down a bit. He knew that the final weeks of a project always seemed to take forever, but he also knew that the project was running almost 2 weeks late as a result of a problem encountered during the excavation phase of the construction project.

During March and April, it appeared that they were catching up. Kyle had discussed with the construction contractor that St. Dismas would pay overtime to catch up, but the speed-up was temporary, and the job continued to be late. Kyle was not quite sure why. Progress just seemed to be in slow motion. He decided to meet with Fred Splient, the President and CEO of St. Dismas, to discuss the problems.

Fred suggested that Kyle call in someone to audit the project, in particular to examine the project schedule carefully. Fred also wanted the auditor to look at the project expenses to date. Fred had just received a crude spreadsheet from the CFO, and it did not reflect the progress he thought should have been made as this project was coming to an end.

Fred asked Kyle to find out if anyone in the hospital's accounting department had experience with projects and project-management software. Kyle knew instantly who to call. Caroline Stevens had once helped him on other hospital projects. Kyle trusted her to act impartially and to be able to figure out what was happening.

Caroline agreed to function as the Project Auditor. She began by examining the most recent project schedule from the construction company. She then created a progress-to-date report with MSP. She also did a complete analysis of the CFO's report. The expense report she reviewed and updated is found below.

Using MSP, Caroline created a graphical progress report on the project as of May 24. She marked the actual progress of each unfinished activity by placing a diamond embedded in a circle on the project's Gantt chart. If the symbol was to the left of the May 24 line, that activity was late; the amount of lateness was indicated by the distance of the symbol to the May 24 line. The symbol for on-time activities rested on the May 24 line. If there had been early activities, their symbols would have been to the right of the May 24 line. Caroline's chart is shown above.

Caroline then scheduled a meeting with Kyle and Fred Splient. She reported that she did see a work slowdown. She conducted interviews with the construction team, and it appeared that they were concerned about their next work assignment. They told her that in the past as projects were coming to a close they were told of their next scheduled job. They had not heard anything yet, and they were worried. She also reported that the interior designer had added seven extra days to complete the interiors (Task #6 of the project) because the carpet and wall coverings might arrive a week late from the manufacturer. They actually arrived on schedule. The estimated remaining duration for the interiors to be completed was 34.6 days. The designer did tell her that the furniture had not all arrived, so they were withholding about 30 percent of the payment until it all arrived.

Caroline also reported to Fred that it appeared that the expenses that were allocated to pay back St. Dismas for such things as preliminary marketing efforts, legal support, etc. had not yet been expensed to the project budget. The only thing that was expensed was the original project construction budget. That budget seemed to be right on track. Kyle reported that he intended to spend the rest of the contingency budget for overtime work by the construction crews. He also intended to use the rest of the IS budget to purchase computers for the common areas of the facility and to wire those areas for access to the Internet. In addition, he was waiting for bills from some of the companies that supplied the required medical equipment. He was planning to spend all that was allocated for that budgeted item. He was over budget on the site improvements and under budget for the kitchen equipment.

Caroline and Fred praised Kyle for his management of the Construction budget.

As soon as Caroline and Kyle left Fred's office, Fred called his CFO to find out why the other items were still not reflected in the project budget.

QUESTIONS

- Estimate the final construction budget.

- What should they do about the work slowdown?

- Create a Gantt chart with the revisions to the duration of the interiors step. When will the project be completed?

- What is the importance of the fact that the Hospital staff expenses were not reported under the project budget?

![]()

Datatech

Steve Bawnson joined Datatech's engineering department upon obtaining his B.S. in Electrical Engineering almost 6 years ago. He soon established himself as an expert in analog signal processing and was promoted to Senior Design Engineer just 2 years after joining the firm. After serving as a Senior Design Engineer for 2 years, he was promoted to Project Manager and asked to oversee a product development project involving a relatively minor product line extension.

As Steve was clearing his desk to make room for a cup of coffee, his computer dinged indicating the arrival of yet another email message. Steve usually paid little attention to the arrival of new email messages, but for some reason this message caught his attention. Swiveling in his chair to face the computer on the credenza behind his desk, he read the subject line of the message: Notebook Computer Development Project Audit Report. Steve then noticed that the message was addressed to the Vice-President of Product Development and was cc: to him. He immediately opened and read the message.

Datatech had recently adopted a policy requiring that all ongoing projects be periodically audited. Last week this policy was implemented and Steve was informed that his project would be the first one audited by a team consisting of internal and external experts.

Datatech Inc. is a full-line producer of desktop and notebook computers that are distributed through a network of value-added resellers. After completing the desktop product line extension project about 9 months ago, Steve was asked to serve as the project manager for a project to develop a new line of notebook computers.

In asking Steve to serve as the project manager for the notebook computer development project, the Vice-President of Product Development conveyed to Steve the importance of completing the project within a year. To emphasize this point, the Vice-President noted that he personally made the decision to go forward with this project and had not taken the project through the normal project selection and approval process in order to save time. Steve had successfully completed the desktop project in a similar timeframe, and told the Vice-President that this target was quite reasonable. Steve added that he was confident that the project would be completed on time and on budget.

Steve wasted no time in planning the project. Based on the success of the desktop project, he decided to modify the work breakdown structure he had developed for the desktop project and apply it to this new project. He recalled the weeks of planning that went into developing the work breakdown structure for the desktop project. The entire project team had been involved, and that was a relatively straightforward product line extension. The current project was more complicated, and there simply was not sufficient time to involve all team members. What was the point of wasting valuable time and resources to re-invent the wheel?

After modifying the work breakdown structure, Steve scheduled a meeting with the Vice-President of Product Development to discuss staffing the project. As was typical of other product development projects at Datatech,

Steve and the Vice-President agreed that the project should be housed within the engineering division. In his capacity as project manager, Steve would serve as liaison to other functional areas such as marketing, purchasing, finance, and production.

As the project progressed, it continued to slip behind schedule. Steve found it necessary to schedule a meeting each week to address how unanticipated activities would be completed. For example, last week the team realized that no one had been assigned to design the hinge system for attaching the screen to the base.

Indeed, Steve found himself increasingly in crisis mode. For example, this morning the manufacturing group sent a heated email to Steve. The manufacturing group noted that they just learned of the notebook computer project and based on the design presented to them, they would not be able to manufacture the printed circuit boards because of the extensive amount of surface mount components required. Steve responded to this message by noting that the engineering group was doing its job and had designed a state-of-the-art notebook computer. He added that it was the manufacturing group's problem to decide how to produce it.

Just as troubling was the crisis that had occurred earlier in the week. The Vice-President of Product Development had requested that the notebook computer incorporate a new type of interface that would allow the notebook computer to synchronize information with a tablet computer Datatech was about to introduce. Steve explained that incorporating the interface into the notebook computer would require changes to about 40 percent of the computer and would delay the introduction by a minimum of several months. Nevertheless, the Vice-President was adamant that the changes be made.

As Steve laid down the audit report, he reflected on its conclusion that the project be terminated immediately. In the judgment of the auditing team, the project had slipped so far behind schedule that the costs to complete it were not justified.

QUESTIONS

- To what extent were the problems facing the notebook computer development project avoidable? What could have been done to avoid these problems?

- Would it make sense to apply a project selection model such as the weighted scoring model to this project to determine if it should be terminated?

- In your opinion, are the types of problems that arose in this situation typical of other organizations? If so, what can organizations in general do to avoid these types of problems?

![]()

Ivory Tower Systems

Ivory Tower Systems (ITS) was founded by two former computer science professors to develop mobile apps for the consumer market that leverage state-of-the-art research in the computer science field. Typically, the company looks for opportunities to apply sophisticated algorithms to practical problems with mass appeal. Its first app used a sophisticated optimization algorithm to create weekly meal plans based on data the users supplied about their food likes and dislikes, and their weekly food budget.

Currently an app is under development code named Tour Guide. While there are many mapping apps currently available that provide directions from one location to another, Tour Guide allows the users to enter their starting location and multiple destinations. Then, based on a proprietary heuristic algorithm, the app would provide the optimal sequence to travel to all destinations and ultimately end at the starting location. It was envisioned that the app would be used by people to plan weekend errands as well as people on vacation to plan sight-seeing days.

The project was originally planned to take 18 months. The project is now in its 16th month, and technical challenges that should have been resolved months ago remain. As a result, the ITS founders decided to hire an external expert in software development projects to audit the project. The audit report is provided in Figure A.

QUESTIONS

- Do you have any concerns about the audit process at ITS? If so, what are they and what changes to their auditing process would you recommend for the future?

- Critique the audit report. What are its strengths and weaknesses?

- What are the pros and cons of using an external auditor in this situation? Which type of auditor would you recommend for this project?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BAKER, N. R., S. G. GREEN, A. S. BEAN, W. BLANK, and S. K. TADISINA. “Sources of First Suggestion and Project Success/Failure in Industrial Research.” Proceedings: Conference on the Management of Technological Innovation. Washington, D.C., 1983. (A groundbreaking, early empirical paper on predictions of project success and failure.)

DEAN, B. V. Evaluating, Selecting, and Controlling R&D Projects. New York: American Management Association, 1968.

INGRAM, T. “Managing Client/Server and Open Systems Projects: A 10-Year Study of 62 Mission-Critical Projects.” Project Management Journal, June 1994.

KIMBALL, R. “Nucor's Strategic Project.” Project Management Journal, September 1988.

MEREDITH, J. R. Private consulting project.

PINTO, J. K., and S. J. MANTEL, Jr. “The Causes of Project Failure.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, November 1990.

PMI, “Mars or Bust,” PM Network, October 2004.

SHENHAR, A. J., O. LEVY, and D. DVIR. “Mapping the Dimensions of Project Success.” Project Management Journal, June 1997.

Wheatley, M. “Making the Cut.” PM Network, June 2009.