The Manager, the Organization, and the Team

Once a project has been selected, the next step is for senior management to choose a project manager (PM). It is the PM's job to make sure that the project is properly planned, implemented, and completed—and these activities will be the subjects of the chapters that follow this one.

While PMs are sometimes chosen prior to a project's selection, the more typical case is that the selection is announced following a meeting between senior management and the prospective PM. This appointment sometimes comes as a complete surprise to the candidate whose only obvious qualification for the job is not being otherwise fully occupied on a task more important than the project (Patterson, 1991). At this meeting, the senior manager describes the project and emphasizes its importance to the parent organization, and also to the future career of the prospective PM. (In the language of the Mafia, “It's an offer you can't refuse.”) Occasionally, the senior manager will add further information about the project including a fixed budget, due date, and scope. This is an offer you must refuse, as politely as possible, because, as we noted in Chapter 1, some flexibility is required and there is little chance that you can be successful in meeting all the overdetermined targets.

After a brief consideration of the project, the PM comes to a tentative decision about what talents and knowledge are apt to be required. The PM and/or a senior manager then calls a meeting of people who have the requisite talent and knowledge, and the planning begins. This is the launch meeting, and we will delay further consideration of it until Chapter 3 in which we take up the planning process in detail. First, we must examine the skills required by the person who will lead a team of individuals to carry out a carefully coordinated set of activities in an organizational setting seemingly designed expressly to prevent cooperation. It is helpful if we make a few mild assumptions to ease the following discussions. First, assume that the project's parent organization is medium-to large-size, and is functionally organized (i.e., organized into functions such as marketing, manufacturing, R&D, human resources, and the like). Further assume that the project has some well-defined components or technologies and that the project's output is being delivered to an arm's-length client. These assumptions are not critical. They merely give a context to our discussions.

Before we proceed, an experienced project manager has suggested that we share with the reader one of her reactions to the materials in this book. To the student or the inexperienced PM, it is the project budgets, the schedules with Gantt charts and PERT/CPM networks, the reports and project management software, and the mysteries of resource allocation to multiple projects that appear to be the meat of the PM's job. But these things are not hard to learn, and once understood, can, for the most part, be managed by making appropriate inputs to project management software. The hard part of project management is playing the many roles of the PM. The hard part is negotiating with stubborn functional managers and clients who have their own legitimate axes to grind. The hard part is keeping the peace among project team members, each of whom knows, and is quick to tell, the proper ways to do things. The hard part is dealing with senior managers who allow their wild guesses about budget and scope made in the early consideration of the project during the selection process to become fixed in concrete. The hard part is being surrounded by the chaos of trying to run a project in the midst of a confused mass of activity representing the normal business of the organization. These PMBOK Guide are the things we discuss in this chapter, because these are the hard parts. PMBOK covers the material in this chapter primarily in Chapter 9 on Human Resources.

![]()

2.1 THE PM'S ROLES

In the previous chapter it was noted that the primary role of the PM was to manage trade-offs. In addition to managing trade-offs, the PM also has several other important roles including serving as a facilitator, communicator, virtual project manager, and convener and chair of meetings.

![]()

Facilitator

First, to understand the PM'S roles, it is useful to compare the PM with a functional manager. The head of a function such as manufacturing or marketing directs the activities of a well-established unit or department of the firm. Presumably trained or raised from the ranks, the functional manager has expertise in the technology being managed. He is an accountant, or an industrial engineer, or a marketing researcher, or a shop foreman, or a . . . . The functional manager's role, therefore, is mainly that of supervisor (literally “overseer”). Because the project's place in the parent organization is often not well defined and does not seem to fit neatly in any one functional division, neither is the PM's place neatly defined. Because projects are often multidisciplinary, the PM rarely has technical competence in more than one or two of the several technologies involved in the project. As a result, the PM is not a competent overseer and thus has a different role. The PM is a facilitator.

Facilitator vs. Supervisor The PM must ensure that those who work on the project have the appropriate knowledge and resources, including that most precious resource, time, to accomplish their assigned responsibilities. The work of a facilitator does not stop with these tasks. For reasons that will be apparent later in this chapter, the project is often beset with conflict—conflict between members of the project team, conflict between the team and senior managers (particularly managers of the functional divisions), conflict with the client and other outsiders. The PM must manage these conflicts by negotiating resolution of them.

Actually, the once sharp distinction between the manager-as-facilitator and the manager-as-supervisor has been softened in recent years. With the slow but steady adoption of the participative management philosophy, the general manager has become more and more like the project manager. In particular, responsibility for the planning and organization of specific tasks is given to the individuals or groups that must perform them, always constrained, of course, by company policy, legality, and conformity to high ethical standards. The manager's responsibility is to make sure that the required resources are available and that the task is properly concluded. The transition from traditional authoritarian management to facilitation continues because facilitation is more effective as a managerial style.

A second important distinction between the PM and the traditional manager is that the former uses the systems approach and the latter adopts the analytical approach to understanding and solving problems. The analytical approach centers on understanding the bits and pieces in a system. It prompts study of the molecules, then atoms, then electrons, and so forth. The systems approach includes study of the bits and pieces, but also an understanding of how they fit together, how they interact, and how they affect and are affected by their environment. The traditionalist manages his or her group (a subsystem of the organization) with a desire to optimize the group's performance. The systems approach manager conducts the group so that it contributes to total system optimization. It has been well demonstrated that if all subsystems are optimized, a condition known as suboptimization, the total system is not even close to optimum performance. (Perhaps the ultimate example of suboptimization is “The operation was a success, but the patient died.”) We take this opportunity to recommend to you an outstanding book on business, The Goal, by Goldratt and Cox (1992). It is an easy-to-read novel and a forceful statement on the power of the systems approach as well as the dangers of suboptimization.

Systems Approach To be successful, the PM must adopt the systems approach. Consider that the project is a system composed of tasks (subsystems) which are, in turn, composed of subtasks, and so on. The system, a project, exists as a subsystem of the larger system, a program, that is a subsystem in the larger system, a firm, which is . . . and so on. Just as the project's objectives influence the nature of the tasks and the tasks influence the nature of the subtasks, so does the program and, above it, the organization influence the nature of the project. To be effective, the PM must understand these influences and their impacts on the project and its deliverables.*

Think for a moment about designing a new airplane—a massive product development project—without knowing a great deal about its power plant, its instrumentation, its electronics, its fuel subsystems—or about the plane's desired mission, the intended takeoff and landing facilities, the intended carrying capacity, and intended range. One cannot even start the design process without a clear understanding of the subsystems that might be a part of the plane and the larger systems of which it will be a part as well as those that comprise its environment.

Given a project and a deliverable with specifications that result from its intended use in a larger system within a known or assumed environment, the PM's job is straightforward. Find out what tasks must be accomplished to produce the deliverable. Find out what resources are required and how those resources may be obtained. Find out what personnel are needed to carry out production and where they may be obtained. Find out when the deliverable must be completed. In other words, the PM is responsible for planning, organizing, staffing, budgeting, directing, and controlling the project; the PM “manages” it. But others, the functional managers for example, will staff the project by selecting the people who will be assigned to work on the project. The functional managers also may develop the technical aspects of the project's design and dictate the technology used to produce it. The logic and illogic of this arrangement will be revisited later in this chapter.

Micromanagement At times, the PM may work for a program manager who closely supervises and second-guesses every decision the PM makes. Such bosses are also quite willing to help by instructing the PM exactly what to do. This unfortunate condition is known as micromanagement and is one of the deadly managerial sins. The PM's boss rationalizes this overcontrol with such statements as “Don't forget, I'm responsible for this project,” “This project is very important to the firm,” or “I have to keep my eye on everything that goes on around here.” Such statements deny the value of delegation and assume that everyone except the boss is incompetent. This overweening self-importance practically ensures mediocre performance, if not outright project failure. Any project successes will be claimed by the boss. Failures will be blamed on the subordinate PM.

There is little a PM can do about the “My way or the highway” boss except to polish the résumé or request a transfer. (It is a poor career choice to work for a boss who will not allow you to succeed.) As we will see later in this chapter, the most successful project teams tend to adopt a collegial style. Intrateam conflict is minimized or used to enhance team creativity, cooperation is the norm, and the likelihood of success is high.

Communicator

The PM must be a person who can handle responsibility. The PM is responsible to the project team, to senior management, to the client, and to anyone else who may have a stake in the project's performance or outcomes. Consider, if you will, the Central Arizona Project (CAP). This public utility moves water from the Colorado River to Phoenix, several other Arizona municipalities, and to some American Indian reservations. The water is transported by a system of aqueducts, reservoirs, pipes, and pumping stations. Besides the routine delivery of water, almost everything done at CAP is a project. Most of the projects are devoted to the construction, repair, and maintenance of their system. Now consider a PM's responsibilities. A maintenance team, for instance, needs resources in a timely fashion so that maintenance can be carried out according to a precise schedule. The PM's clients are municipalities. The drinking public (water, of course) is a highly interested stakeholder. The system is even subject to partisan political turmoil because CAP-supplied water is used as a political football in Tucson.

The PM is in the middle of this muddle of responsibility and must manage the project in the face of all these often-conflicting interests. CAP administration, the project teams, the municipalities (and their Native American counterparts), and the public all communicate with each other—often contentiously. In general, we often call this the “context” of the project. More accurately, given the systems approach we have adopted, this is the environment of the project.

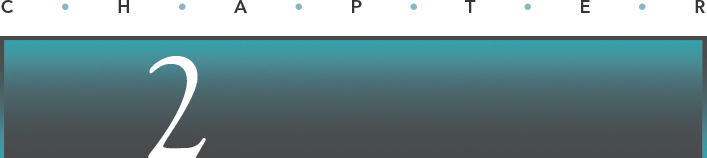

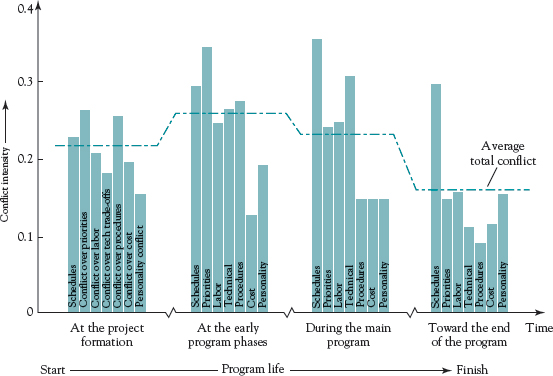

Figure 2-1 shows the PM's position and highlights the communication problem involved in any project. The solid lines denote the PM's communication channels. The dotted lines denote communication paths for the other parties-at-interest in the project. Problems arise when some of these parties propagate communications that may mislead other parties, or directly conflict with other messages in the system. It is the PM's responsibility to introduce some order into this communication mess.

Figure 2-1 Communication paths between a project's parties-at-interest.

For example, assume that senior management calls for tighter cost control or even for a cost reduction. The project team may react emotionally with a complaint that “They want us to cut back on project quality!” The PM must intervene to calm ruffled team feathers and, perhaps, ask a senior manager to reassure the project team that high quality is an organizational objective though not every gear, cog, and cam needs to be gold-plated.

Similarly, the client may drop in to check on a project and blithely ask a team member, “Would it be possible to alter the specs to include such-and-such?” The team member may think for a moment about the technical problems involved and then answer quite honestly, “Yeah, that could be done.” Again, the PM must intervene—if and when the question and answer come to light—to determine the cost of making such a change, as well as the added time that would be required. The PM must then ask whether the client wishes to alter the project scope given the added cost and delayed delivery. This scenario is so common it has a name, scope creep. It is the PM's nightmare.

![]()

Virtual Project Manager

More and more often, project teams are geographically dispersed. Many projects are international, and team members may be on different continents, for example, aircraft engine design and engine construction. Many are carried out by different organizations in different locations. For example, Boeing created global supplier/strategic partner teams for their new 787 Dreamliner aircraft to co-design and produce various portions of the new plane: the vertical fin in Seattle, WA, the cockpit in Wichita, KS, the wings in Japan, and the center fuselage in Italy. Similarly, many projects involve different divisions of one firm where the divisions are in different cities. These geographically dispersed projects are often referred to as “virtual projects, possibly because so much of the intra-project communication is conducted via email, through websites, by telephone or video conferencing, and other high-technology methods. In recent decades, the international dispersion of industry, “globalization,” has dramatically increased the communication problems, adding the need for translators to the virtual communication networks. An interesting view of “virtual” people who work in one country but live in another (often on another continent) is given in a Wall Street Journal article (Flynn, 1999).

Long-distance communication is commonplace and no longer prohibitively expensive. It may, however, be beset with special problems. In the case of written and voice-only communication (and even in video conferencing when the camera is not correctly aimed), the communicators cannot see one another. In such cases we realize how much we depend on feedback—the facial expression and body language that let us know if our messages are received and with what level of acceptance. Two-way, realtime communication is the most effective way to transmit information or instructions. For virtual projects to succeed, communication between PM and project team must be frequent, open, and two-way.

The PM's responsibility for communication with senior management poses special problems for any PM without fairly high levels of self-confidence. Formal and routine progress reports aside (cf. Chapter 7), it is the PM's job to keep senior management up to date on the state of the project. It is particularly important that the PM keep management informed of any problems affecting the project—or any problem likely to affect the project in the future. A golden rule for anyone is “Never let the boss be surprised!” Violations of this rule will cost the PM credibility, trust, and possibly his or her job. Where there is no trust, effective communication ceases. Senior management must be informed about a problem in order to assist in its solution. The timing of this information should be at the earliest point a problem seems likely to occur. Any later is too late. This builds trust between the PM and senior managers. The PM who is trusted by the project champion and can count on assistance when organizational clout is needed is twice blessed.

The PM is also responsible to the client. Clients are motivated to stay in close touch with a project they have commissioned. Because they support the project, they feel they have a right to intercede with suggestions (requests, alterations, demands). Cost, schedule, and scope changes are the most common outcome of client intercession, and the costs of these changes often exceed the client's expectations. Note that it is not the PM's job to dissuade the client from changes in the project's scope, but the PM must be certain that the client understands the impact of the changes on the project's goals of delivery time, cost, and scope.

The PM is responsible to the project team just as team members are responsible to the PM. As we will see shortly, it is very common for project team members to be assigned to work on the project, but to report to a superior who is not connected with the project. Thus, the PM will have people working on the project who are not “direct reports.” Nonetheless, the relationship between the team and the PM may be closer to boss-subordinate than one might suspect. The reason for this is that both PM and team members often develop a mutual commitment to the project and to its successful conclusion. The PM facilitates the work of the team, and helps them succeed. As we will see in the final chapter, the PM may also take an active interest in fostering team members' future careers. Like any good boss, the PM may serve as advisor, counselor, confessor, and interested friend.

Meetings, Convener and Chair

The two areas in which the PM communicates most frequently are reports to senior management and instructions to the project team. We discuss management reports in Chapter 7 on monitoring and controlling the project. We also set out some rules for conducting successful meetings in Chapter 7. Communication with the project team typically takes place in the form of project team meetings. When humorist Dave Barry reached 50, he wrote a column listing 25 things he had learned in his first 50 years of living. Sixteenth on the list is “If you had to identify, in one word, the reason why the human race has not and never will achieve its full potential, that word would be ‘meetings’.”

Most of the causes of meeting-dread are associated with failure to adopt common sense about when to call meetings and how to run them. As we have said, one of the first things the PM must do is to call a “launch meeting” (see Chapter 3). Make sure that the meeting starts on time and has a prearranged stopping time. As convener of the meeting, the PM is responsible for taking minutes and keeping the meeting on track. The PM should also make sure that the invitation to the meeting includes a written agenda that clearly explains the purpose for the meeting and includes sufficient information on the project to allow the invitees to come prepared—and they are expected to do so. For some rules on conducting effective meetings that do not result in angry colleagues, see the subsection on meetings in Chapter 7.

The PM is a facilitator, unlike the traditional manager who is a supervisor. The PM must adopt the systems approach to making decisions and managing projects. Trying to optimize each part of a project, suboptimization, does not produce an optimized project. Multiple communication paths exist in any project, and some paths bypass the PM, causing problems. Much project communication takes place in meetings that may be run effectively if some simple rules are followed. In virtual projects much communication is via high technology channels. Above all, the PM must keep senior management informed about the current state of the project.

2.2 THE PM'S RESPONSIBILITIES TO THE PROJECT

The PM has three overriding responsibilities to the project. First is the acquisition of resources and personnel. Second is dealing with the obstacles that arise during the course of the project. Third is exercising the leadership needed to bring the project to a successful conclusion and making the trade-offs necessary to do so.

![]()

Acquiring Resources

Acquiring resources and personnel is not difficult. Acquiring the necessary quality and quantity of resources and personnel is, however. Senior management typically suffers from a mental condition known as “irrational optimism.” While the disease is rarely painful to anyone except PMs, the suffering among this group may be quite severe.

It has long been known that the farther one proceeds up the managerial ladder, the easier, faster, and cheaper a job appears to be compared to the opinion of the person who has to do the work (Gagnon and Mantel, 1987). The result is that the work plan developed by the project team may have its budget and schedule cut and then cut again as the project is checked and approved at successively higher levels of the organization. At times, an executive in the organization will have a strong interest in a pet project. In order to improve the chance that the pet project will be selected, the executive may deliberately (or subconsciously) understate the resource and personnel commitments required by the project. Whatever the cause, it is the PM's responsibility to ensure that the project has the appropriate level of resources. When the project team needs specific resources to succeed, there is no acceptable excuse for not getting them—though there may be temporary setbacks.

When a human resource is needed, the problem is further complicated. Most human resources come to the project on temporary assignment from the functional departments of the organization. The PM's wants are simple—the individual in the organization who is most competent on the specific task to be accomplished. Such individuals are, of course, precisely the people that the functional managers are least happy to release from their departmental jobs for work on the project, either full- or part-time. Those workers the functional manager is prone to offer positions are usually those whom the PM would least like to have.

Lack of functional manager enthusiasm for cooperation with the project has another source. In many organizations, projects are seen as glamorous, interesting, and high-visibility activities. The functional manager may be jealous or even suspicious of the PM who is perceived to have little or no interest in the routine work that is the bread and butter for the parent organization.

Fighting Fires and Obstacles

Still another key responsibility of the PM is to deal with obstacles. All projects have their crises—fires that must be quenched. The successful PM is also a talented and seasoned fire fighter. Early in the project's life cycle, fires are often linked to the need for resources. Budgets get cut, and the general cuts must be transformed into highly specific cuts in the quantities of highly specific resources. An X percent cut must be translated into Y units of this commodity or Z hours of that engineer's time. (An obvious reaction by the PM is to pad the next budget submitted. As we argue just below and in Chapters 4 and 6, this is unethical, a bad idea, and tends to cause more problems than it solves.)

As work on the project progresses, most fires are associated with technical problems, supplier problems, and client problems. Technical problems occur, for example, when some subsystem (e.g., a computer routine) is supposed to work but fails. Typical supplier problems occur when subcontracted parts are late or do not meet specifications. Client problems tend to be far more serious. Most often, they begin when the client asks “Would it be possible for this thing to . . .?” Again, scope creep.

Most experienced PMs are good fire fighters. If they do not develop this skill, they do not last as PMs. People tend to enjoy doing what they are skilled at doing. Be warned: When you find a skilled fire fighter who fights a lot of fires and enjoys the activity, you may have found an arsonist. At one large, highly respected industrial firm we know, there is a wisecrack commonly made by PMs. “The way to get ahead around here is to get a project, screw it up, and then fix it. If it didn't get screwed up, it couldn't have been very hard or very important.” We do not believe that anyone purposely botches projects (or knowingly allows them to be botched). We do, however, suspect that the attitude breeds carelessness because of the belief that they can fix any problem and be rewarded for it.

Leadership and Making Trade-Offs

In addition to being responsible for acquiring resources for the project and for fighting the project's fires, the PM is also responsible for making the trade-offs necessary to lead the project to a successful conclusion. As noted in the previous chapter, the primary role of the PM is managinge trade-offs and as such this issue is a key feature of the remainder of this book. In each of the following chapters and particularly in the chapters on budgeting, scheduling, resource allocation, and control, we will deal with many examples of trade-offs. They will be specific. At this point, however, we should establish some general principles.

![]()

The PM is the key figure in making trade-offs between project cost, schedule, scope, and risk. Which of these has higher priority than the others is dependent on many factors having to do with the project, the client, and the parent organization. If cost is more important than time for a given project, the PM will allow the project to be late rather than incur added costs. If a project has successfully completed most of its specifications, and if the client is willing, both time and cost may be saved by not pursuing some remaining specifications. It is the client's choice.

Of the three project goals, scope (specifications and client satisfaction) is usually the most important. Schedule is a close second, and cost is usually subordinate to the other two. Note the word “usually.” There is anecdotal evidence that economic downturns result in an increased level of importance given to cost. There are many other exceptions, and this is another case where the political acuity of the PM is of primary importance. While deliverables are almost always paramount when dealing with an “arm's-length” client, it is not invariably so for an inside client. If the parent firm has inadequate profits, some specifications may be sacrificed for cost savings. Organizational policy may influence trade-offs. Grumman Aircraft (now a part of Northrop-Grumman) had a longstanding policy of on-time delivery. If a Grumman project for an outside client fell behind on its schedule, resources (costs) were added to ensure on-time delivery.

The global financial crisis is causing headaches for project managers around the world. Swanson (2009) reports that in Hong Kong there are now thousands of PMs from China suddenly available and willing to manage projects for substantially lower than prevailing wages. As a result, Hong Kong PMs are finding that they need to increase their value to business in order to compete with the new arrivals from China. Because the Hong Kong firms are now outsourcing many project tasks, the Hong Kong PMs are acquiring new skill sets to deal with people and organizations with whom they have not previously dealt. They are learning networking, communication, and leadership skills to augment their technical skills. They also focus on delivering “business” results such as increased revenues, improved profit margins, cost reductions, and they make sure that these appear in the organization's financial statements.

Another type of trade-off occurs between projects. At times, two or more projects may compete for access to the same resources. This is a major subject in Chapter 6, but the upshot is that added progress on one project may be traded off for less progress on another. If a single PM has two projects in the same part of the project life cycle and makes such a trade-off, it does not matter which project wins, the PM will lose. We strongly recommend that any PM managing two or more projects do everything possible to avoid this problem by making sure that the projects are in different phases of their life cycles. We urge this with the same fervor we would urge parents never to act so as to make it appear that one child is favored over another.

Negotiation, Conflict Resolution, and Persuasion

It is not possible for the PM to meet these responsibilities without being a skilled negotiator and resolver of conflict. The acquisition of resources requires negotiation. Dealing with problems, conflict, and fires requires negotiation and conflict resolution. The same skills are needed when the PM is asked to lead the project to a successful conclusion—and to make the trade-offs required along the way.

In Chapter 1 we emphasized the presence of conflict in all projects and the resultant need for win-win negotiation and conflict resolution. A PM without these skills cannot be successful. There is no stage of the project life cycle that is not characterized by specific types of conflict. If these are not resolved, the project will suffer and possibly die. For new PMs, training in win-win negotiation is just as important as training in PERT/CPM, budgeting, project management software, and project reporting. Such training is not merely useful, it is a necessary requirement for success. While an individual who is not (yet) skilled in negotiation may be chosen as PM for a project, the training should start immediately. A precondition is the ability to handle stress. Much has been written about negotiation and conflict resolution; there is no need to repeat it here. We refer you again to the bibliography for Chapter 1.

Projects must be selected for funding, and they begin when senior management has been persuaded that they are worthwhile. Projects almost never proceed through their life cycles without change. Changes in scope are common. Trade-offs may change what deliverable is made, how it is made, and when it is delivered. Success at any of these stages depends on the PM's skill at persuading others to accept the project as well as changes in its methods and scope once it has been accepted. Any suggested change will have supporters and opponents. If the PM suggests a change, others will need to be persuaded that the change is for the better. Senior management must be persuaded to support the change just as the client and the project team may need to be persuaded to accept change in the deliverables or in the project's methods or timing.

Persuasion is rarely accomplished by “my way or the highway” commands. Neither can it be achieved by locker-room motivational speeches. In an excellent article in the Harvard Business Review, Jay Conger (1998) describes the skill of persuasion as having four essential parts: (1) effective persuaders must be credible to those they are trying to persuade; (2) they must find goals held in common with those being persuaded; (3) they must use “vivid” language and compelling evidence; and (4) they must connect with the emotions of those they are trying to persuade. The article is complete with examples of each of the four essential parts.

![]()

The PM is responsible for acquiring the human and material resources needed by the project. The PM is also responsible for exercising leadership, fire fighting, and dealing with obstacles that impede the project's progress. Finally, the PM is responsible for making the trade-offs between budget, schedule, and scope that are needed to ensure project success. To be successful at meeting these responsibilities, the PM must be skilled at negotiation, conflict resolution, and persuasion.

2.3 SELECTION OF A PROJECT MANAGER

A note to senior management: It is rarely a good idea to select a project manager from a list of engineers (or other technical specialists) who can be spared from their current jobs at the moment. Unfortunately, in many firms this appears to be the primary criterion for choice. We do not argue that current availability is not one among several appropriate criteria, but that it is only one of several—and never the most important. Neither does the list of criteria begin with “Can leap over tall buildings with a single bound.”

The most important criterion, by far, is that the prospective PM, in the language of sales people, is a “closer.” Find individuals who complete the tasks they are given. As any senior manager knows, hard workers are easy to find. What is rare is an individual who is driven to finish the job. Given a set of such people, select those who meet the following criteria at reasonably high levels.

Credibility

For the PM, credibility is critical. In essence, it means that the PM is believable. There are two areas in which the PM needs believability. The first is technical credibility, and the second is administrative credibility. The PM is not expected to have an expert's knowledge of each of the technologies that may be germane to the project. The PM should, however, have expertise in one or more areas of knowledge relevant to the project. In particular, the PM must know enough to explain the current state of the project, its progress, and its technical problems to senior management who may lack technical training. The PM should also be able to interpret the wishes of management and the client to the project team (Grant, Baumgardner, and Stone, 1997; Matson, 1998).

While quite different, administrative credibility is just as significant to the project. For management and the client to have faith in the viability of the project, reports, appraisals, audits, and evaluations must be timely and accurate. For the team, resources, personnel, and knowledge must be available when needed. For all parties, the PM must be able to make the difficult trade-offs that allow the project to meet its objectives as well as possible. This requires mature judgment and considerable courage.

![]()

Sensitivity

There is no need to belabor what should, by now, be obvious. The PM needs a finely tuned set of political antennae as well as an equally sensitive sensor of interpersonal conflict between team members, or between team members (including himself or herself) and other parties-at-interest to the project. As we will see, open and honest intrateam communication is critical to project success. Also needed are technical sensors that indicate when technical problems are being swept under the rug or when the project is about to fall behind its schedule.

Leadership, Style, Ethics

A leader is someone who indicates to other individuals or groups the direction in which they should proceed. When complex projects are decomposed into a set of tasks and subtasks, it is common for members of the project to focus on their individual tasks, thereby ignoring the project as a whole. This fosters the dreaded suboptimization that we mentioned early in this chapter. Only the PM is in a position to keep team members working toward completion of the whole project rather than its parts. In practice, leaders keep their people energized, enthusiastic, well organized, and well informed. This, in turn, will keep the team well motivated.

At the beginning of this chapter, we noted that the PM's role should be facilitative rather than authoritarian. Now let us consider the style with which that role is played. There has been much research on the best managerial style for general management, and it has been assumed that the findings apply to PMs as well. Recent work has raised some questions about this assumption. While there is little doubt that the most effective overall style is participative, Professor Shenhar of the Stevens Institute of Technology adds another dimension to style (1998). He found that as the level of technological uncertainty of a project went from “low tech” to “very high tech,” the appropriate management style (while being fundamentally participative) went from “firm” to “highly flexible.” In addition, he found that the complexity of the project, ranked from “simple” to “highly complex,” called for styles varying from “informal” to “highly formal.” To sum up, the more technically uncertain a project, the more flexible the style of management should be. The more complex a project, the more formal the style should be. In this context, flexibility applies primarily to the degree that new ideas and approaches are considered. Formality applies primarily to the degree to which the project operates in a structured environment.

Professor Shenhar's work has the feeling of good sense. When faced with technological uncertainty, the PM must be open to experimentation. In the same way, if a project is highly complex with many parts that must be combined with great care, the PM cannot allow a haphazard approach by the project team. In the end, the one reasonably sure conclusion about an effective management style for PMs is that it must be participative. Autocrats do not make good project managers.

Another aspect of leadership is for the PM to have—and to communicate—a strong sense of ethics. In recent years, the number and severity of unethical practices by business executives (and politicians) have increased dramatically. Because projects differ from one to another, there are few standard procedures that can be installed to ensure honest and ethical behavior from all parties-at-interest to the project. One has only to read a daily paper to find examples of kickbacks, bribery, covering up mistakes, use of substandard materials, theft, fraud, and outright lies on project status or performance. Dishonesty on anyone's part should not be permitted in projects.

Due, however, to the increasing number of multicultural projects, it is easy to make ethical missteps when managing a project in an unfamiliar country. Jones (2008) notes that what may be common practice in one country may be illegal in another—paying (bribing) a government agent to fast-track an approval, leaving out obvious information in a bid, inviting a client (or being invited) to dinner, and so on. Discovering another culture's ethical standards is difficult. One can engage local partners who have demonstrated knowledge of a local culture and are willing to share their information. Organizations should ensure that their employees are trained to recognize potential ethical issues and to communicate anything that seems amiss with their superiors. Insisting that employees follow the highest ethical standards, both domestic and foreign, may result in the firm having to abandon a project or a bid when it compromises those standards, but having a solid reputation for integrity will be a strong long-run benefit to the firm.

The Project Management Institute (PMI) has developed a Code of Ethics for the profession. The Code is the thoughtful result of an extended discussion and debate on ethical conduct in the project management profession. A new version of the Code, resulting from even more extended discussions, appeared in 2006. It is roughly eight times the length of the earlier version, including two Appendices. The new Code is available to anyone at the PMI website, www.PMI.org.

The new Code should be read carefully by anyone contemplating a career in project management. It accents behavior that will lead to high trust levels among team members, and between the team and the client and senior management as well as other stakeholders. The section titled “Honesty” should be reread . . . and reread . . . and reread. We will revisit the subjects of honesty and trust throughout this book.

Successful PMs have some common characteristics. They are “closers.” They also have high administrative and technical credibility, show sensitivity to interpersonal conflict, and possess the political know-how to get help from senior management when needed. In addition, the PM should be a leader, and adopt a participatory management style that may have to be modified depending on the level of technological sophistication and uncertainty involved in the project. Another critical project management skill is the ability to direct the project in an ethical manner.

2.4 PROJECT MANAGEMENT AS A PROFESSION

It should be obvious to the reader that project management is a demanding job. Planning and controlling the complexities of a project's activities, schedule, and budget would be difficult even if the project had the highest claim on the parent organization's knowledge and resources, and if the PM had full authority to take any action required to keep the project on course for successful completion. Such is never the case, but all is not lost because there are tools available to bring some order to the chaos of life as a PM—to cope with the difficulties of planning and the uncertainties that affect budgets and schedules. Also, as we have indicated, it is possible to compensate for missing authority through negotiation. Mastering the use of project management tools requires specialized knowledge that is often acquired through academic preparation, which is to say that project management is a profession. The profession comes complete with career paths and an excellent professional organization.

The Project Management Institute (PMI) was founded in 1969. By 1990, the PMI had 7500 members. It grew to 17,000 by 1995, but 5 years later membership had exploded to more than 64,000. By 2012, the PMI had more than 380,000 members worldwide. The exponential growth of the PMI is the result of the exponential growth in the use of projects and PMs as a way of getting things done. For example, a senior vice president of an international chemical firm installed project management as a way of controlling the workloads on his technical specialists and on a few overloaded facilities—project management having tools to handle the allocation of scarce resources. In another instance, a new CEO of a large hospital mandated that all nonroutine, onetime operations be managed as projects so that she could have information on the nature and status of all such activities.

In Chapter 1 we mentioned the project-oriented organization. In these firms all nonroutine activities are organized as projects. In addition, the process of instituting change in routine operations is also commonly organized as a project. The motives behind this approach to handling change are the same as those motivating the chemical firm VP and the hospital CEO, the need to control and to have information about what is happening in the organization.

![]()

To establish standards for project management and to foster professionalism in the field, the PMI has codified the areas of learning required to manage projects. This Project Management Body of Knowledge, 5th edition (PMBOK) has been compiled into a book published by the PMI, also available as a CD. It serves as a basis for practice and education in the field (PMI Standards Committee, 2013). PMBOK devotes Chapter 9 to human resource management, including organizational planning, staffing, and team development. The PMI also publishes two important periodicals: first, the Project Management Journal, oriented to project management theory, though its articles are almost uniformly related to the actual practice of project management; and second, the PM Network magazine, which is a trade journal aimed at practitioners. Both publications are valuable for the experienced PM as well as the neophyte or student. The PMI also offers certification testing programs for project managers. By 2013, almost 500,000 individuals had been certified by the PMI as Project Management Professionals (PMPs) or as Certified Associates in Project Management (CAPM).

The fantastic variety of projects being conducted today ranges from esoteric research on gene identification to specialized maintenance of machine tools. A quick glance at any daily paper will describe multiple projects such as cleaning up the image of downtown, improving air quality in various global cities, and reports of projects concerning natural disasters such as earthquakes.

Opportunities for careers in project management abound, but where can people who are competent to manage projects be found, or how can they be trained? A rapidly growing number of colleges, universities, and technical institutes have developed courses and degree programs in project management. In recent years, many local chapters of the PMI have also offered training programs of varying length and depth. Nonetheless, the demand for project managers far exceeds the supply. (PMI Today, a supplement to PM Network, is recommended for more information on training and employment opportunities.)

The career path for the PM usually starts with work on a small project, and then on some larger projects. If the individual survives life as a project worker, graduation to the next level comes in the form of duty as a “project engineer” or as a “deputy” PM for a project. Then comes duty as the manager of a small project, and then as PM of larger ones. All of this, of course, presumes a track record of success.

The highest visibility for a PM is to manage a “megaproject,” either successfully or unsuccessfully. As Gale (2009) points out, success is defined as bringing the megaproject in on time and on budget. There is no room for error. The main difference between a “normal” project and a megaproject is that the technical issues tend to disappear on a megaproject. Instead, the PM's hardest tasks are those of communicating, managing vendors and contractors, dealing with stakeholders, running smooth task processes, guiding the project team, engaging the client, helping map the project to the business objectives, and handling the political and cultural issues.

![]()

A professional organization, the Project Management Institute (PMI) has been devoted to project management. The growth in the field has been exponential. Among other reasons for this growth is the project-oriented organization. The PMI has published the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK). It also publishes two professional periodicals. Many courses and degree programs in project management are available. Project management has numerous career possibilities.

2.5 FITTING PROJECTS INTO THE PARENT ORGANIZATION

![]()

Earlier in this chapter we referred several times to problems caused by the way projects are organized and fit in as a part of the parent organization. It is now time to deal with this subject. Project organization is also discussed in Chapter 2: Organizational Influences and Project Life Cycle of PMBOK. It would be most unusual for a PM to have any influence over the interface between the project and the parent organization. This arrangement is a matter of company policy and usually is decided by senior management. The nature of the interface, however, has a major impact on the PM's life, and it is necessary that the PM understand why senior managers make what appears to be the worst of all possible choices for the interface.

More on “Why Projects?”

Before examining the alternative ways in which a project can interface with the organization, it is useful to add to our understanding of just why organizations choose to conduct so much of their work as projects. We spoke previously of project-oriented firms. In addition to the managerial reasons that caused the rapid spread of such organizations, there were also strong economic reasons. First, devising product development programs by integrating product design, engineering, manufacturing, and marketing functions in one team not only improved the product, it also allowed significant cuts in the time-to-market for the product. For example, in the 1990s Chrysler Motors (now owned by Fiat) cut almost 18 months from the new product development time required for design-to-street and produced designs that were widely rated as outstanding. This brought new Chrysler models to market much faster than normal in the automotive industry. Quite apart from the value of good design, the economic value of the time saved is immense and derives from both reduced design labor and overhead, plus earlier sales and return on the investment—in this case amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars. The same methods were used to enable General Motors to redesign and reimage their Cadillac and Buick models in response to the sharp decline in demand during the steep business downturn of 2008. This same process also allows a firm to tailor special versions of standard products for individual clients. We will have more to say about this process at the end of this chapter.

Second, the product development/design process requires input from different areas of specialized knowledge. The exact mix of knowledge varies from product to product or service to service. Teams of specialists can be formed, do their work, and disband. The make-up of such teams can easily be augmented or changed.

Third, the explosive expansion of technical capabilities in almost every area of the organization tends to destabilize the structure of the enterprise. Almost all industries have experienced the earthquakes of changed technology, revamped software systems, altered communication systems; followed by mergers, downsizing, spin-offs, and other catastrophes—all of which require system-wide responsiveness. Dealing with the threat of climate change is going to require massive, worldwide changes in technology. It will undoubtedly involve the use of multifirm, multiindustry, and multinational projects to develop and implement the necessary technological changes. Traditional organizations have difficulty dealing with rapid, large-scale change, but project organizations can.

Fourth, like our hospital CEO, many upper-level managers we know lack confidence in their ability to cope with and respond to such large-scale, rapid change in their organizations. Organizing these changes as projects gives the managers some sense of accountability and control.

Finally, the rapid growth of globalized industry often involves the integration of activities carried out by different firms located in different countries, often on different continents. Organizing such activities into a project improves the firm's ability to ensure overall compliance with the laws and regulations of dissimilar governments as well as with the policies of widely assorted participating firms.

All these factors fostered the expanded use of projects, but traditional ways of organizing projects were too costly and too slow, largely because of how they linked to the parent firm. In the years following World War II, projects came into common use. Most of the early projects were created to solve large-scale government problems, many of which were related to national defense—the building of an intercontinental ballistic missile, the construction of an interstate highway system, the development and deployment of a missile defense system, and similar massive projects (Hughes, 1998). At the same time, private industry tentatively began to use projects to develop new medicinal drugs, larger and faster commercial airliners, large-scale computing machines, shopping malls, and apartment complexes with hundreds of units. All such projects had several things in common: They were large, complex, and often required the services of hundreds of people. The natural way to organize such projects came to be known as the pure project organization.

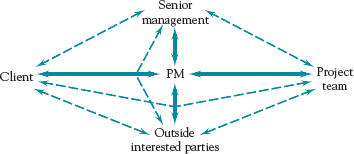

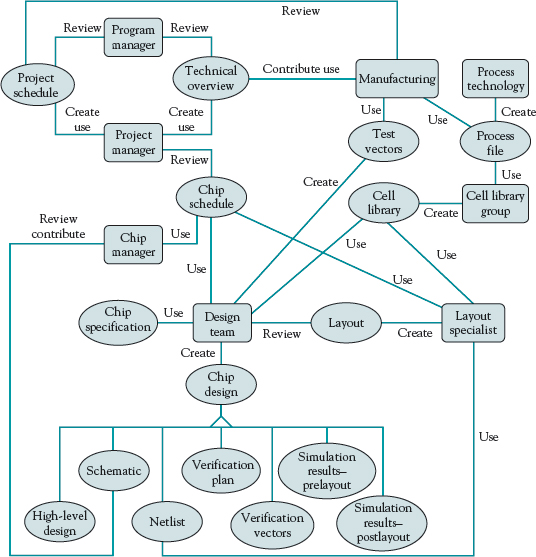

Pure Project Organization

Consider the construction of a football stadium or a shopping mall. Assume that the land has been acquired and the design approved. Having won a competitive bid, a contractor assigns a project manager and a team of construction specialists to the project. Each specialist, working from the architectural drawings, develops a set of plans to deal with his or her particular specialty area. One may design and plan the electrical systems, another the mechanicals, still another the parking and landscaping, and so forth. In the meantime, someone is arranging for the timely delivery of cranes, earth movers, excavation equipment, lumber, cement, brick, and other materials. And someone is hiring a suitable number of local construction workers with the appropriate skills. See Figure 2-2 for a typical pure project organization.

The supplies, equipment, and workers arrive just when they are needed (in a perfect world), do the work, complete the project, and disband. The PM is, in effect, the CEO of the project. When the project is completed, accepted by the client, equipment returned, and local workers paid off, then the PM and the specialists return to their parent firm and await the next job.

For large projects, the pure project organization is effective and efficient, but for small projects it is a very expensive way to operate. In the preceding example, we assumed that there was always work for each member of the labor force. On a very large project, that assumption is approximately true. On a small project, the normal ebb and flow of work is not evened out as it is on large projects with a large number of workers. On small projects, therefore, it is common to find personnel shortages one week and overages the next. Also, on small projects the human resources person or the accountant is rarely needed full-time. Often such staff persons may be needed one-quarter or one-half time; but humans do not come in fractions. They are always integers. Remember also that pure projects are often carried out at some distance from the home office, and a quarter-time accountant cannot go back to the home office when work on the project slacks off. Part-time workers are not satisfactory either. They never seem to be on site when they are needed.

There are other drawbacks to the pure project. While they have a broad range of specialists, they have limited technological depth. If the project's resident specialist in a given area of knowledge happens to be lacking in a specific subset of that area, the project must hire a consultant, add another specialist, or do without. If the parent organization has several concurrent pure projects drawing on the same specialty areas, they develop fairly high levels of duplication in these specialties. This is expensive.

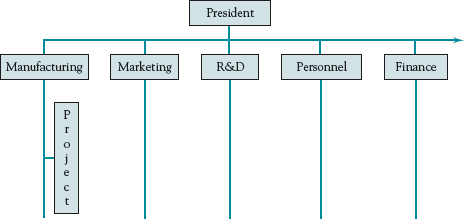

Figure 2-2 Pure project organization.

There are other problems, and one of the most serious is seen in R&D projects or in projects that have fairly long lives. People assigned to the project tend to form strong attachments to it. The project begins to take on a life of its own. A disease we call “projectitis” develops. One pronounced symptom is worry about “Is there life after the project?” Foot dragging as the project end draws near is common, as is the submission of proposals for follow-up projects in the same area of interest—and, of course, using the same project team.

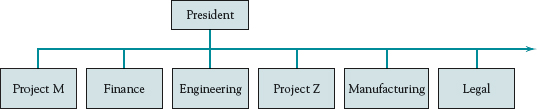

Functional Project Organization

Some projects have a very different type of structure. Assume, for example, that a project is formed to install a new production machine in an operating production line. The project includes the removal of the old machine and the integration of the new machine into the production system. In such a case, we would probably organize the project as an appendage to the Manufacturing division where the production system is located. Figure 2-3 shows a typical example of functional project organization with the project in this case, attached to the manufacturing function.

Quite unlike pure projects that are generally separated from the day-to-day operations of the parent organization, functionally organized projects are embedded in the functional group where the project will be used. This immediately corrects some of the problems associated with pure projects. First, the functional project has immediate, direct, and complete contact with the most important technologies it may need, and it has in-depth access. Second, the fractional resource problem is minimized for anyone working in the project's home functional group. Functionally organized projects do not have the high personnel costs associated with pure projects because they can easily assign people to the project on a part-time basis. Finally, even projectitis will be minimal because the project is not removed from the parent organization and specialists are not divorced from their normal career tracks.

There are, however, two major problems with functionally organized projects. First, communications across functional department boundaries are rarely as simple as most firms think they are. When technological assistance is needed from another division, it may or may not be forthcoming on a timely basis. Technological depth is certainly present, but technological breadth is missing. The same problem exists with communication outside the function. In the pure project, communication lines are short and messages move rapidly. This is particularly important when the client is sending or receiving messages. In most functionally organized projects, the lines of communication to people or units outside the functional division are slow and tortuous. Traditionally, messages are not to be sent outside the division without clearing through the division's senior management. Insisting that project communications follow the organizational chain of command imposes impossible delays on most projects. It most certainly impedes frank and open communication between project team members and the project client.

Figure 2-3 Functional project organization.

Another major problem besets functionally organized projects. The project is rarely a high-priority item in the life of the division. The task of Manufacturing is to produce product. The job of Marketing is to sell. Manufacturing may have a sincere interest in a new machine or Marketing in a new product, but those projects do not make “here and now” contributions to the major objectives of the divisions. We have already noted the tendency of managers to focus on short-run goals. After all, managerial bonuses are usually linked to short-run performance. Given this bias, functionally organized projects often get short shrift from their sponsoring divisions.

Matrix Project Organization

In an attempt to capture the advantages of both the pure project and the functionally organized project as well as to avoid the problems associated with each type, a new type of project organization—more accurately, a combination of the two—was developed.

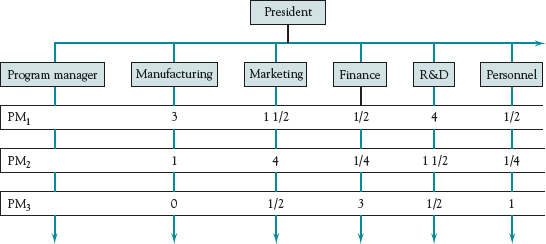

To form a matrix organized project, a pure project is superimposed on a functionally organized system as in Figure 2-4. The PM reports to a program manager or a vicepresident of projects or some senior individual with a similar title whose job it is to coordinate the activities of several or all of the projects. These projects may or may not be related, but they all demand the parent's resources and the use of resources must be coordinated, if not the projects themselves. This method of organizing the interface between projects and the parent organization succeeds in capturing the major advantages of both pure and functional projects. It does, however, create some problems that are unique to this matrix form. To understand both the advantages and disadvantages, we will examine matrix management more closely.

As the figure illustrates, there are two distinct levels of responsibility in a matrix organization. First, there is the normal functional hierarchy that runs vertically in the figure and consists of the regular departments such as marketing, finance, manufacturing, human resources, and so on. (We could have illustrated a bank or university or an enterprise organized on some other principle. The departmental names would differ, but the structure of the system would be the same.) Second, there are horizontal structures, the projects that overlay the functional departments and, presumably, have some access to the functional department's competencies. Heading up these horizontal projects are the project managers.

Figure 2-4 Matrix project organization.

A close examination of Figure 2-4 shows some interesting details. Project 1 has assigned to it three people from the Manufacturing division, one and one-half from Marketing, a half-time person from Finance, four from R&D, and one-half from Personnel, plus an unknown number from other divisions not shown in the figure. Other projects have different make-ups of people assigned. This is typical of projects that have different objectives. Project 2, for example, appears to be aimed at the development of a new product with its concentration of Marketing representation, plus significant assistance from R&D, representation from Manufacturing, and staff assistance from Finance and Personnel. The PM controls what these people do and when they do it. The head of a functional group controls who from the group is assigned to the project and what technology is appropriate for use on the project.

Advantages We can disregard the problems raised by the split authority for the moment and concentrate on the strong points of this arrangement. Because there are many possible combinations of the pure project and the functional project, the matrix project may have some characteristics of each organizational type. If the matrix project closely resembles the pure project with many individuals assigned full-time to the project, it is referred to as a “strong” matrix or a “project” matrix. If, on the other hand, functional departments assign resource capacity to the project rather than people, the matrix is referred to as a “weak” matrix or a “functional” matrix. The project might, of course, have some people and some capacity assigned to it, in which case it is sometimes referred to as a “balanced” matrix. (The Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines “balanced” as “being in harmonious or proper arrangement . . .” In no way does the balanced matrix qualify as “balanced.”) None of the terms—strong, weak, balanced—is precise, and matrix projects may be anywhere along the continuum from strong to weak. It may even be stronger or weaker at various times during the project's life.

The primary reason for choosing a strong or weak matrix depends on the needs of both the project and the various functional groups. If the project is likely to require complex technical problem solving, it will probably have the appropriate technical specialists assigned to it. If the project's technology is less demanding, it will be a weaker matrix that is able to draw on a functional group's capacity when needed. A firm manufacturing household oven cleaners might borrow chemists from the R&D department to develop cleaning compounds that could dissolve baked-on grease. The project might also test whether such products were toxic to humans by using the capacity of the firm's Toxicity Laboratory rather than having individual toxicity testers assigned to the project team.

One of the most important strengths of the matrix form is this flexibility in the way it can interface with the parent organization. Because it is, or can be, connected to any or all of the parent organization's functional units, it has access to any or all of the parent organization's technology. The way it utilizes the services of the several technical units need not be the same for each unit. This allows the functional departments to optimize their contributions to any project. They can meet a project's needs in a way that is most efficient. Being able to share expertise with several projects during a limited time period makes the matrix arrangement far less expensive than the pure project with its duplication of competencies, and just as technologically “deep” as the functional project. The flexibility of the matrix is particularly useful for globalized projects that often require integrating knowledge and personnel coming from geographically dispersed independent business units, each of which may be organized quite differently than the others.

The matrix has a strong focus on the project itself, just as does the pure project. In this, it is clearly superior to the functional project that often is subordinate to the regular work of the functional group. In general, matrix organized projects have the advantages of both pure and functional projects. For the most part, they avoid the major disadvantages of each. Close contact with functional groups tends to mitigate projectitis. Individuals involved with matrix projects are never far from their home department and do not develop the detached feelings that sometimes strike those involved with pure projects.

Disadvantages With all their advantages, matrix projects have their own, unique problems. By far the most significant of these is the violation of an old dictum of the military and of management theory, the Unity of Command principle: For each subordinate, there shall be one, and only one, superior. In matrix projects, the individual specialist borrowed from a function has two bosses. As we noted above, the project manager may control which tasks the specialist undertakes, but the specialist reports to a functional manager who makes decisions about the specialist's performance evaluation, promotion, and salary. Thus, project workers are often faced with conflicting orders from the PM and the functional manager. The result is conflicting demands on their time and activities. The project manager is in charge of the project, but the functional manager is usually superior to the PM on the firm's organizational chart, and may have far more political clout in the parent organization. Life on a matrix project is rarely comfortable for anyone, PM or worker.

As we have said, in matrix organizations the PM controls administrative decisions and the functional heads control technological decisions. This distinction is simple enough when writing about project management, but for the operating PM the distinction, and partial division of authority and responsibility, is complex indeed. The ability of the PM to negotiate anything from resources to technical assistance to delivery dates is a key contributor to project success. As we have said before and will certainly say again, success is doubtful for a PM without strong negotiating skills.

While the ability to balance resources, schedules, and deliverables between several projects is an advantage of matrix organization, that ability has its dark side. The organization's full set of projects must be carefully monitored by the program manager, a tough job. Further, the movement of resources from project to project in order to satisfy the individual schedules of the multiple projects may foster political infighting among the several PMs. As usual, there are no winners in these battles. Naturally, each PM is more interested in ensuring success for his or her individual project than in maintaining general organization-wide goals. Not only is this suboptimization injurious to the parent organization, it also raises serious ethical issues. In Chapter 1 we discussed some of the issues involved in aggregate planning, and we will have much more to say on this matter in Chapter 6.

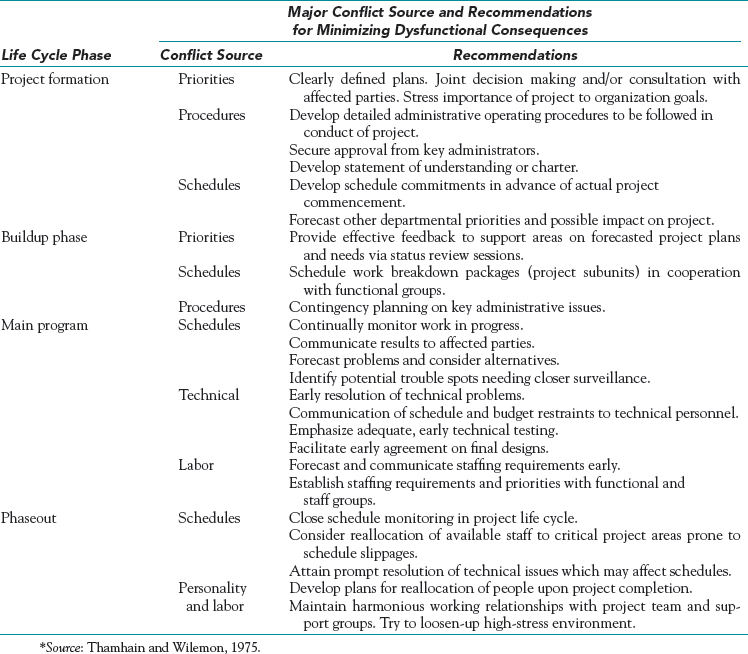

Intrateam conflict is a characteristic of all projects, but the conflicts seem to us to be particularly numerous and contentious in matrix projects. In addition to conflicts arising from the split authority and from the violation of Unity of Command, another major source of conflict appears to be inherent in the nature of the transdisciplinary teams in a matrix setting. Functional projects have such teams, but team members have a strong common interest, their common functional home. Pure projects have transdisciplinary teams, but the entire team is full-time and committed to the project. Matrix project teams are transdisciplinary, but team members are often not full-time, have different functional homes, and have other commitments than the project. They are often committed to their functional area or to their career specialty, rather than to the project. As we emphasize in the next section, high levels of trust between project team members is critical for optimum team performance. Conflicts do not necessarily lead to distrust on a project team, but unless matrix organized teams are focused on the project rather than on their individual contribution to it, distrust between team members is almost certain to affect project outcomes negatively.

Figure 2-5 Mixed project organization.

A young man of our acquaintance works one-quarter time on each of two projects and half-time in his functional group, the mechanical engineering group in an R&D division. He estimates that approximately three-quarters of the time he is expected to be in two or more places at the same time. He indicated that this is normal.

With all its problems, there is no real choice about project organization for most firms. Functional projects are too limited and too slow. Pure projects are far too expensive. Matrix projects are both effective and efficient. They are here to stay, conflict and all.

Mixed Organizational Systems

Functional, matrix, and pure projects exist side by side in some organizations (see Figure 2-5). In reality, they are never quite as neatly defined as they appear here. Matrix or functional projects may be organized, become very successful and expand into pure projects. It may not stop there, with the pure project growing into an operating division of the parent firm, perhaps becoming a subsidiary or even a stand-alone, venture firm. There are many such cases (e.g., Texas Instruments and the Speak and Spell toy developed by one of its employees).

The ability to organize projects to fit the needs of the parent firm has allowed projects to be used under conditions that might be quite difficult were project organization constrained to one or two specific forms. As the hybridization increases, though, the firm risks increasing the level of conflict in and between projects because of duplication, overlapping authority, and increased friction between project and functional management.

The Project Management Office and Project Maturity

There is another way of solving some of the problems of choosing one or another organizational form for projects. The parent organization can set up a project management office (PMO), more or less like a functional group. This group may act as staff to some or to all projects (Block, 1998; Bolles, 1998). The project office may handle some or all of the budgeting, scheduling, reporting, scope, compliance with corporate governance, and risk management activities while the functional units supply the technical work. The PMO often serves as a repository for project documents and histories. However, the PMO must never replace the project manager as officer in charge of and accountable for the project.

![]()

This approach is particularly useful when the system operates many small projects with short lives. For example, facility maintenance projects may be operated this way. Maintenance team leaders act as PMs, and the PMO keeps the records and makes reports. Because the teams are semi-permanent groups, they develop techniques for working together and often specialize in specific types of maintenance problems. Reports and records are standardized, and the system has few of the administrative problems of many maintenance systems.

At times the PMO is effective, and at times it is not. Based on limited observation, it appears to us that the system works well when the functional specialists have fairly routine projects. If this is not the case, the team must be involved in generating the project's budget, schedule, and scope, and must be kept well informed about the progress of the project measured against its goals. Some years ago, a large pharmaceutical firm used a similar arrangement on R&D projects, the purpose being to “protect” their scientists from having to deal with project schedules, budgets, and progress reports, all of which were handled by the PMO. The scientists were not even bothered with having to read the reports. The result was precisely what one might expect. All projects were late and over budget—very late and far over budget.

But in another case, the US Federal Transportation Security Administration had only 3 months and $20 million to build a 13,500 square foot coordination center, involving the coordination of up to 300 tradespeople working simultaneously on various aspects of the center (PMI, May 2004). A strong Project Management Office was crucial to making the effort a success. The PMO accelerated the procurement and approval process, cutting times in half in some cases. They engaged a team leader, a master scheduler, a master financial manager, a procurement specialist, a civil engineer, and other specialists to manage the multiple facets of the construction project, finishing the entire project in 97 days and on budget, receiving an award from the National Assn. of Industrial and Office Properties for the quality of its project management and overall facility.

In general, however, the role of the PMO is much broader than this example, and it is now not uncommon to find several different types of PMOs existing at different levels of large firms with different, but sometimes overlapping, areas of operation. They have titles such as CPMO for Corporate Project Management Office, or EPMO for Enterprise Project Management Office, and many other variants. It is also common to find an EPMO (or CPMO) followed by a PMO for each unit of the parent organization that actually carries out the projects and reports to the senior EPMO.

Involvement of senior management in EPMOs allows the EPMO to provide some important functions. The EPMO (or PMO if there is only one in the firm) is in a unique position to maintain oversight of the entire portfolio of projects carried out by the firm, acting as a project selection committee, making sure that the set of projects is consistent with the firm's strategies, generating and insuring compliance with matters of corporate governance, maintaining project histories as well as composite data on project costs, schedules, etc., setting project or program priorities across departments, helping projects to acquire resources, and similar issues. Project champions, senior managers who have a strong interest in a project or program and may use their political clout to help the project with priority issues or resource acquisition when such clout may be useful, are often appropriate members of the EPMOs. Again, care must be taken for the EPMO or its individual members to avoid usurping the PM as the accountable, officer-in-charge of the project.

While such activities are necessary and, indeed, helpful, EPMO actions sometimes may cause significant management problems. Because many senior managers have little or no training in project management, they tend to focus on assessment of project progress and evaluation by using planned cost versus actual cost as a primary measurement tool. (We will discuss the problems caused by this simplistic measure several times in the following chapters, and in some detail in Chapter 7 on Project Control.) As senior management has become aware of these and other problems, many EPMOs have taken on the task of assuring that the organization is following “best practices” for the management of its projects. The EPMO is expected to monitor and continuously improve the organization's project management skills. In the past few years, a number of different ways to measure this “project management maturity” (Pennypacker et al., 2003) have been suggested, such as basing the evaluation on PMI's PMBOK Guide (Lubianiker, 2000; see also www.pmi.org) or the ISO 9001 standards of the International Organization for Standardization.

![]()

![]()

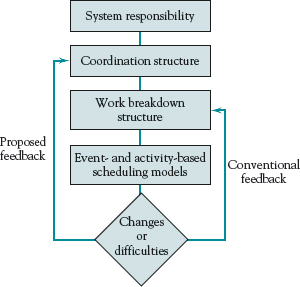

Quite a few consulting firms, as well as scholars, have devised formal maturity measures; one such, PM3, is described by R. Remy (1997). In this system, the final project management “maturity” of an organization is assessed as being at one of five levels: ad-hoc (disorganized, accidental successes and failures); abbreviated (some processes exist, inconsistent management, unpredictable results); organized (standardized processes, more predictable results); managed (controlled and measured processes, results more in line with plans); and adaptive (continuous improvement in processes, success is normal, performance keeps improving).

![]()

Another maturity model was applied to 38 organizations in four industries (Ibbs and Kwak, 2000). The survey included 148 questions covering six processes/life cycle phases (initiating, planning, executing, controlling, closing, and project-driven organization environment) and ten PMBOK knowledge areas (integration, scope, time, cost, quality, human resources, communication, risk, procurement, and stakeholders). The model assesses project management maturity in terms of five stages called: ad hoc, planned, managed, integrated, and sustained.

![]()

Regardless of the model form, it appears that most organizations do not score very well in maturity tests. On one form, about three-quarters are no higher than level 2 (planned) and fewer than 6 percent are above level 3. Individual firms ranged from 1.8 to 4.6 on the five-point scale.