The World of Project Management

Once upon a time there was a heroine project manager. Her projects were never late. They never ran over budget. They always met contract specifications and invariably satisfied the expectations of her clients. And you know as well as we do, anything that begins with “Once upon a time . . .” is just a fairy tale.

This book is not about fairy tales. Throughout these pages we will be as realistic as we know how to be. We will explain project management practices that we know will work. We will describe project management tools that we know can help the project manager come as close as Mother Nature and Lady Luck will allow to meeting the expectations of all who have a stake in the outcome of the project.

1.1 WHAT IS A PROJECT?

Why this emphasis on project management? The answer is simple: Daily, organizations are asked to accomplish work activities that do not fit neatly into business-as-usual. A software group may be asked to develop an application program that will access U.S. government data on certain commodity prices and generate records on the value of commodity inventories held by a firm; the software must be available for use on April 1. The Illinois State Bureau for Children's Services may require an annually updated census of all Illinois resident children, aged 17 years or younger, living with an illiterate single parent; the census must begin in 18 months. A manufacturer initiates a process improvement project to offset higher energy costs.

Note that each work activity is unique with a specific deliverable aimed at meeting a specific need or purpose. These are projects. The routine issuance of reports on the value of commodity inventories, the routine counseling of single parents on nurturing their offspring, the day-to-day activities associated with running a machine in a factory—these are not projects. The difference between a project and a nonproject is not always crystal clear. For almost any precise definition, we can point to exceptions. At base, however, projects are unique, have a specific deliverable, and have a specific due date. Note that our examples have all those characteristics. The Project Management Institute (PMI) defines in its Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 5th edition, a project as “A temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result” (Project Management Institute, 2013).

![]()

Projects vary widely in size and type. The writing of this book is a project. The reorganization of Procter & Gamble (P&G) into a global enterprise is a project, or more accurately a program, a large integrated set of projects. The construction of a fly-in fishing lodge in Manitoba, Canada, is a project. The organization of “Cat-in-the-Hat Day” so that Mrs. Payne's third grade class can celebrate Dr. Suess's birthday is also a project.

Both the hypothetical projects we mentioned earlier and the real-world projects listed just above have the same characteristics. They are unique, specific, and have desired completion dates. They all qualify as projects under the PMI's definition. They have an additional characteristic in common—they are multidisciplinary. They require input from people with different kinds of knowledge and expertise. This multidisciplinary nature of projects means that they tend to be complex, that is, composed of many interconnected elements and requiring input from groups outside the project. The various areas of knowledge required for the construction of the fly-in fishing lodge are not difficult to imagine. The knowledge needed for globalization of a large conglomerate like P&G is quite beyond the imagination of any one individual and requires input from a diversified group of specialists. Working as a team, the specialists investigate the problem to discover what information, skills, and knowledge are needed to accomplish the overall task. It may take weeks, months, or even years to find the correct inputs and understand how they fit together.

A secondary effect of using multidisciplinary teams to deal with complex problems is conflict. Projects are characterized by conflict. As we will see in later chapters, the project schedule, budget, and specifications conflict with each other. The needs and desires of the client conflict with those of the project team, the senior management of the organization conducting the project and others who may have a less direct stake in the project. Some of the most intense conflicts are those between members of the project team. Much more will be said about this in later chapters. For the moment, it is sufficient to recognize that projects and conflict are often inseparable companions, an environment that is unsuitable and uncomfortable for conflict avoiders.

It is also important to note that projects do not exist in isolation. They are often parts of a larger entity or program, just as projects to develop a new engine and an improved suspension system are parts of the program to develop a new automobile. The overall activity is called a program. Projects are subdivisions of programs. Likewise, projects are composed of tasks, which can be further divided into subtasks that can be broken down further still. The purpose of these subdivisions is to allow the project to be viewed at various levels of detail. The fact that projects are typically parts of larger organizational programs is important for another reason, as is explained in Section 1.5.

Finally, it is appropriate to ask, “Why projects?” The reason is simple. We form projects in order to fix the responsibility and authority for the achievement of an organizational goal on an individual or small group when the job does not clearly fall within the definition of routine work.

Trends in Project Management

Many recent developments in project management are being driven by quickly changing global markets, technology, and education. Global competition is putting pressure on prices, response times, and product/service innovation. Computer and telecommunication technology, along with rapidly expanding higher education across the world allows the use of project management for types of projects and in regions where these sophisticated tools had never been considered before. The most important of these recent developments are covered in this book.

Achieving Strategic Goals There has been a growing use of projects to achieve an organization's strategic goals, and existing major projects are screened to make sure that their objectives support the organization's strategy and mission. Projects that do not have clear ties to the strategy and mission are not approved. A discussion of this is given in Section 1.6, where the Project Portfolio Process is described.

Achieving Routine Goals On the other hand, there has also been a growing use of project management to accomplish routine departmental tasks, normally handled as the usual work of functional departments; e.g., routine machine maintenance. Middle management has become aware that projects are organized to accomplish their performance objectives within their budgets and deadlines. As a result, artificial deadlines and budgets are created to accomplish specific, though routine, departmental tasks—a process called “projectizing.”

![]()

Improving Project Effectiveness A variety of efforts are being pursued to improve the process and results of project management, whether strategic or routine. One well-known effort is the creation of a formal Project Management Office (PMO, see Section 2.5) in many organizations that takes responsibility for many of the administrative and specialized tasks of project management. Another effort is the evaluation of an organization's project management “maturity,” or skill and experience in managing projects (discussed in Section 7.5). This is often one of the responsibilities of the PMO. Another responsibility of the PMO is to educate project managers about the ancillary goals of the organization (Section 8.1), which automatically become a part of the goals of every project whether the project manager knows it or not. Achieving better control over each project through the use of phase gates (Sections 7.1 and 7.4), earned value (Section 7.3), critical ratios (Section 7.4), and other such techniques is also a current trend.

![]()

Virtual Projects With the rapid increase in globalization of industry, many projects now involve global teams whose members operate in different countries and different time zones, each bringing a unique set of talents to the project. These are known as virtual projects because the team members may never physically meet before the team is disbanded and another team reconstituted. Advanced telecommunications and computer technology allow such virtual projects to be created, do their work, and complete their project successfully (see Section 2.1).

Quasi-Projects Led by the demands of the information technology/systems departments, project management is now being extended into areas where the project's objectives are not well understood, time deadlines unknown, and/or budgets undetermined. This ill-defined type of project is extremely difficult to conduct and to date has often resulted in setting an artificial due date and budget, and then specifying project objectives to meet those limits. However, new tools for these quasi-projects are now being developed—prototyping, phase-gating, and others—to help these projects achieve results that satisfy the customer in spite of the unknowns.

![]()

A project, then, is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product or service. It is specific, timely, usually multidisciplinary, and typically conflict ridden. Projects are parts of overall programs and may be broken down into tasks, subtasks, and further if desired. Current trends in project management include achieving strategic goals, achieving routine goals, improving project effectiveness, virtual projects, and quasi-projects.

1.2 PROJECT MANAGEMENT VS. GENERAL MANAGEMENT

As is shown in Table 1-1, project management differs from general management largely because projects differ from what we have referred to as “nonprojects.” The naturally high level of conflict present in projects means that the project manager (PM) must have special skills in conflict resolution. The fact that projects are unique means that the PM must be creative and flexible, and have the ability to adjust rapidly to changes. When managing nonprojects, the general manager tries to “manage by exception.” In other words, for nonprojects almost everything is routine and is handled routinely by subordinates. The manager deals only with the exceptions. For the PM, almost everything is an exception.

Major Differences

Certainly, general management's success is dependent on good planning. For projects, however, planning is much more carefully detailed and project success is absolutely dependent on such planning. The project plan is the result of integrating all information about a project's deliverables, generally referred to as the “scope” of the project, and its targeted date of completion. “Scope” has two meanings. One is “product scope,” which defines the performance requirements of a project, and “project scope,” which details the work required to deliver the product scope (see Chapter 5, p. 105 PMBOK Guide of PMBOK, 2013). To avoid confusion, we will use the term scope to mean “product scope” and will allow the work, resources, and time needed by the project to deliver the product scope to the customer to be defined by the project's plan (discussed in detail in Chapter 3). Therefore, the scope and due date of the project determine its plan, that is, its budget, schedule, control, and evaluation. Detailed planning is critically important. One should not, of course, take so much time planning that nothing ever gets done, but careful planning is a major contributor to project success. Project planning is discussed in Chapter 3 and is amplified throughout the rest of this book.

![]()

Table 1-1 Comparison of Project Management and General Management

Project budgeting differs from standard budgeting, not in accounting techniques, but in the way budgets are constructed. Budgets for nonprojects are primarily modifications of budgets for the same activity in the previous period. Project budgets are newly created for each project and often cover several “budget periods” in the future. The project budget is derived directly from the project plan that calls for specific activities. These activities require resources, and such resources are the heart of the project budget. Similarly, the project schedule is also derived from the project plan.

In a nonproject manufacturing line, the sequence in which various things are done is set when the production line is designed. The sequence of activities often is not altered when new models are produced. On the other hand, each project has a schedule of its own. Previous projects with deliverables similar to the one at hand may provide a rough template for the current project, but its specific schedule will be determined by the time required for a specific set of resources to do the specific work that must be done to achieve each project's specific scope by the specific date on which the project is due for delivery to the client. As we will see in later chapters, the special requirements associated with projects have led to the creation of special managerial tools for budgeting and scheduling.

The routine work of most organizations takes place within a well-defined structure of divisions, departments, sections, and similar subdivisions of the total unit. The typical project cannot thrive under such restrictions. The need for technical knowledge, information, and special skills almost always requires that departmental lines be crossed. This is simply another way of describing the multidisciplinary character of projects. When projects are conducted side-by-side with routine activities, chaos tends to result—the nonprojects rarely crossing organizational boundaries and the projects crossing them freely. These problems and recommended actions are discussed at greater length in Chapter 2.

Even when large firms establish manufacturing plants or distribution centers in different countries, a management team is established on site. For projects, “globalization” has a different meaning. Individual members of project teams may be spread across countries, continents, and oceans, and speak several different languages. Some project team members may never even have a face-to-face meeting with the project manager, though transcontinental and intercontinental video meetings combining telephone and computer are common.

The discussion of structure leads to consideration of another difference between project and general management. In general management, there is a reasonably well defined managerial hierarchy. Superior-subordinate relationships are known, and lines of authority are clear. In project management this is rarely true. The PM may be relatively low in the hierarchical chain of command. This does not, however, reduce his or her responsibility of completing a project successfully. Responsibility without the authority of rank or position is so common in project management as to be the rule, not the exception.

Negotiation

With little legitimate authority, the PM depends on negotiation skills to gain the cooperation of the many departments in the organization that may be asked to supply technology, information, resources, and personnel to the project. The parent organization's standard departments have their own objectives, priorities, and personnel. The project is not their responsibility, and the project tends to get the leftovers, if any, after the departments have satisfied their own need for resources. Without any real command authority, the PM must negotiate for almost everything the project needs.

It is important to note that there are three different types of negotiation, win-win negotiation, win-lose negotiation, and lose-lose negotiation. When you negotiate the purchase of a car or a home, you are usually engaging in win-lose negotiation. The less you pay for a home or car, the less profit the seller makes. Your savings are the other party's losses—win-lose negotiation. This type of negotiation is never appropriate when dealing with other members of your organization. If you manage to “defeat” a department head and get resources or commitments that the department head did not wish to give you, imagine what will happen the next time you need something from this individual. The PM simply cannot risk win-lose situations when negotiating with other members of the organization.

Lose-lose negotiation occurs when one party is unwilling to assert his or her position aggressively while at the same time resists cooperating with the other party. This often occurs in situations where one or both of the parties are conflict avoiders. When one party is not willing to help the other party achieve his or her objective and at the same time is unwilling to pursue his or her own objectives, the end result is that both parties lose.

Within the organization, win-win negotiation is mandatory. In essence, in win-win negotiation both parties must try to understand what the other party needs. The problem you face as a negotiator is how to help other parties meet their needs in return for their help in meeting the needs of your project. When negotiation takes place repeatedly between the same individuals, win-win negotiation is the only sensible procedure. PMs spend a great deal of their time negotiating. General managers spend relatively little. Skill at win-win negotiating is a requirement for successful project managing (see Fisher and Ury, 1983; Jandt, 1987; and Raiffa, 1982).

One final point about negotiating: Successful win-win negotiation often involves taking a synergistic approach by searching for the “third alternative.” For example, consider a product development project focusing on the development of a new printer. A design engineer working on the project suggests adding more memory to the printer. The PM initially opposes this suggestion, feeling that the added memory will make the printer too costly. Rather than rejecting the suggestion, however, the PM tries to gain a better understanding of the design engineer's concern.

Based on their discussion, the PM learns that the engineer's purpose in requesting additional memory is to increase the printer's speed. After benchmarking the competition, the design engineer feels the printer will not be competitive as it is currently configured. The PM explains his fear that adding the extra memory will increase the cost of the printer to the point that it also will no longer be cost competitive. Based on this discussion the design engineer and PM agree that they need to search for another (third) alternative that will increase the printer's speed without increasing its costs. A couple of days later, the design engineer identifies a new ink that can simultaneously increase the printer's speed and actually lower its total and operating costs.

Project management differs greatly from general management. Every project is planned, budgeted, scheduled, and controlled as a unique task. Unlike nonprojects, projects are often multidisciplinary and usually have considerable need to cross departmental boundaries for technology, information, resources, and personnel. Crossing these boundaries tends to lead to intergroup conflict. The development of a detailed project plan based on the scope and due date of the project is critical to the project's success.

Unlike their general management counterparts, project managers have responsibility for accomplishing a project, but little or no legitimate authority to command the required resources from the functional departments. The PM must be skilled at win-win negotiation to obtain these resources.

1.3 WHAT IS MANAGED? THE THREE GOALS OF A PROJECT

The performance of a project is measured by three criteria. Is the project on time or early? Is the project on or under budget? Does the project deliver the agreed-upon specification to the satisfaction of the customer? Figure 1-1 shows the three goals of a project. The performance of the project and the PM is measured by the degree to which these goals are achieved.

One of these goals, the project's specifications or “scope,” is set primarily by the client (although the client agrees to all three when contracting for the project). It is the client who must decide what capabilities are required of the project's deliverables—and this is what makes the project unique. Some writers insist that “quality” is a separate and distinct goal of the project along with time, cost, and scope. We do not agree because we consider quality an inherent part of the project specifications.

If we did not live in an uncertain world in which best made plans often go awry, managing projects would be relatively simple, requiring only careful planning. Unfortunately, we do not live in a predictable (deterministic) world, but one characterized by chance events (uncertainty). This ensures that projects travel a rough road. Murphy's law seems as universal as death and taxes, and the result is that the most skilled planning is upset by uncertainty. Thus, the PM spends a great deal of time adapting to unpredicted change. The primary method of adapting is to trade-off one objective for another. If a construction project falls behind schedule because of bad weather, it may be possible to get back on schedule by adding resources—in this case, probably labor using overtime and perhaps some additional equipment. If the budget cannot be raised to cover the additional resources, the PM may have to negotiate with the client for a later delivery date of the building. If neither cost nor schedule can be negotiated, the client may be willing to cut back on some of the features in the building in order to allow the project to finish on time and budget (e.g., substituting carpet for tile in some of the spaces). As a final alternative, the contractor may have to “swallow” the added costs (or pay a penalty for late delivery) and accept lower profits.

![]()

This example illustrates a fundamental point. Namely, managing the tradeoffs among the three project goals is in fact the primary role of the project manager. Furthermore, managing these trade-offs in the most effective manner requires that the project manager have a clear understanding of how the project supports broader organizational goals. Thus, the organization's overall strategy is the most important consideration for managing the trade-offs that will be required among the three project goals.

Figure 1-1 Scope, cost, and time project performance targets.

All projects are always carried out under conditions of uncertainty. Well-tested software routines may not perform properly when integrated with other well-tested routines. A chemical compound may destroy cancer cells in a test tube—and even in the bodies of test animals—but may kill the host as well as the cancer. Where one cannot find an acceptable way to deal with a problem, the only alternative may be to stop the project and start afresh to achieve the desired deliverables.

As we note throughout this book, projects are all about uncertainty. Therefore, in addition to effectively managing trade-offs, effective project management requires an ability to deal with uncertainty. The time required to complete a project, the availability and costs of key resources, the timing of solutions to technological problems, a wide variety of macroeconomic variables, the whims of a client, the actions taken by competitors, even the likelihood that the output of a project will perform as expected, all these exemplify the uncertainties encountered when managing projects. While there are actions that may be taken to reduce the uncertainty, no actions of a PM can ever eliminate it.

As Hatfield (2008) points out, projects are complex and include interfaces, interdependencies, and many assumptions, any or all of which may turn out to be wrong. Also, projects are managed by people, which adds to the uncertainty. Gale (2008a) reminds us that the uncertainties include everything from legislation that can change how we do business, to earthquakes and other “acts of God.” Therefore, in today's turbulent business environment, effective decision making is predicated on an ability to manage the ambiguity that arises while we operate in a world characterized by uncertain information. (Risk management is discussed in Chapter 11 of the PMBOK, 5th ed., 2013.)

![]()

![]()

The first step in managing risk is to identify these potentially uncertain events and the likelihood that any or all may occur. This is called risk analysis. Different managers and organizations approach this problem in different ways. Gale advises expecting the unexpected; some managers suggest considering those things that keep one awake at night. Many organizations keep formal lists, a “risk register,” and use their Project Management Office (PMO, discussed in Chapter 2) to maintain and update the list of risks and approaches that have been successful in the past in dealing with specific risks. This information is then incorporated into the firm's business-continuity and disaster-recovery plans. Every organization should have a well-defined process for dealing with risk, and we will discuss this issue at greater length in Chapter 3, Section 3.5. At this point we simply overview risk analysis.

![]()

The essence of risk analysis is to make estimates or assumptions about the probability distributions associated with key parameters and variables and to use analytic decision models or Monte Carlo simulation models based on these distributions to evaluate the desirability of certain managerial decisions. Real-world problems are usually large enough that the use of analytic models is very difficult and time consuming. With modern computer software, simulation is not difficult.

A mathematical model of the situation is constructed, and a simulation is run to determine the model's outcomes under various scenarios. The model is run (or replicated) repeatedly, starting from a different point each time based on random choices of values from the probability distributions of the input variables. Outputs of the model are used to construct statistical distributions of items of interest to decision makers, such as costs, profits, completion dates, or return on investment. These distributions are the risk profiles of the outcomes associated with a decision. Risk profiles can be analyzed by the manager when considering a decision, along with many other factors such as strategic concerns, behavioral issues, fit with the organization, cost and scheduling issues, and so on.

![]()

Thus we observe that in addition to managing trade-offs, another critical aspect of project management is managing uncertainty or risk. In fact, managing risk is actually tightly coupled with managing the three traditional goals of project management. For example, the more uncertainty the project manager faces, the greater the risk that the project will go over budget, finish late, and/or not meet its original scope. However, beyond these rather obvious relationships, there is also a more subtle connection. In particular, project risk represents a fourth trade-off opportunity at the project manager's disposal. For example, the project's budget can be increased in order to collect additional data that in turn will reduce the uncertainty related to how long it will take to complete the project. Likewise, the project's deadline can be reduced, but this will increase the uncertainty about whether it will be completed on time.

As a result of the relationship between uncertainty and the three traditional project goals, we adopt the view in this book that managing uncertainty is a fourth goal of project management. Thus, the primary role of the project manager is to effectively manage the trade-offs between cost, time, scope, and risk.

![]()

In the past, it was popular to label technical uncertainties as “technological risk.” This is not very helpful, however, because it is not the technology that is uncertain. We can, in fact, do almost anything we wish, excepting perhaps faster-than-light travel and perpetual motion. What is uncertain is not technological success, but rather how much it will cost and how long it will take to reach success.

![]()

Most of the trade-offs PMs make are reasonably straightforward if the organization's strategy is well understood and trade-offs are discussed during the planning, budgeting, and scheduling phases of the project. Usually they involve trading time and cost, but if we cannot alter either the schedule or the budget, the specifications of the project may be altered or additional risk accepted. Frills on the finished product may be foregone, capabilities not badly needed may be compromised. From the early stages of the project, it is the PM's duty to know which elements of project performance are sacrosanct.

One final comment on this subject: Projects must have some flexibility. Again, this is because we do not live in a deterministic world. Occasionally, a senior manager (who does not have to manage the project) presents the PM with a document precisely listing a set of deliverables, a fixed budget, and a firm schedule. This is failure in the making for the PM. Unless the budget is overly generous, the schedule overlong, and the deliverables easily accomplished, the system is, as mathematicians say, “overdetermined.” If Mother Nature so much as burps, the project will fail to meet its rigid parameters. A PM cannot be successful without flexibility to manage the trade-offs.

Projects have four interrelated objectives: to (1) meet the budget, (2) finish on schedule, (3) generate deliverables that satisfy the client, and (4) to minimize risks. Because we live in an uncertain world, as work on the project proceeds, unexpected problems are bound to arise. These chance events will threaten the project's schedule or budget or scope. The PM must now decide how to trade off one project goal against another (e.g., to stay on schedule by assigning extra resources to the project may mean it will run over the predetermined budget). If the schedule, budget, and scope are rigidly predetermined, the project is probably doomed to failure unless the preset schedule and budget are overly generous or the difficulty in meeting the specifications has been seriously overestimated.

1.4 THE LIFE CYCLES OF PROJECTS

All organisms have a life cycle. They are born, grow, wane, and die. This is true for all living things, for stars and planets, for the products we buy and sell, for our organizations, and for our projects as well. A project's life cycle measures project completion as a function of either time (schedule) or resources (budget). The subject of project life cycles is discussed in PMBOK's Chapter 2 on Organizational Influences and Project Life Cycle. This life cycle must be understood because the PM's managerial focus subtly shifts at different stages of the cycle (Adams and Barndt, 1983; Kloppenborg and Mantel, 1990). During the early stages, the PM must make sure that the project plan really reflects the wishes of the client as well as the abilities of the project team and is designed to be consistent with the goals and objectives of the parent organization.

![]()

![]()

As the project goes into the implementation stage of its life cycle, the PM's attention turns to the job of keeping the project on budget and schedule—or, when chance interferes with progress, to negotiating the appropriate trade-offs to correct or minimize the damage. At the end of the project, the PM turns into a “fuss-budget” to assure that the specifications of the project are truly met, handling all the details of closing out the books on the project, making sure there are no loose ends, and that every “i” is dotted and “t” crossed.

Many projects are like building a house. A house-building project starts slowly with a lot of discussion and planning. Then construction begins, and progress is rapid. When the house is built, but not finished inside, progress appears to slow down and it seemingly takes forever to paint everything, to finish all the trim, and to assemble and install the built-in appliances. Progress is slow-fast-slow, as shown in Figure 1-2.

It used to be thought that the S-shaped curve of Figure 1-2 represented the life cycle for all projects. While this is true of many projects, there are important exceptions. Anyone who has baked a cake has dealt with a project that approaches completion by a very different route than the traditional S-curve, as shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-2 The project life cycle.

Figure 1-3 An alternate project life cycle.

The process of baking a cake is straightforward. The ingredients are mixed while the oven is preheated, usually to 350°F. The mixture (technically called “goop”) is placed in a greased pan, inserted in the oven, and the baking process begins. Assume that the entire process from assembling the ingredients to finished cake requires about 45 minutes—15 minutes for assembling the materials and mixing, and 30 minutes for baking. At the end of 15 minutes we have goop. Even after 40 minutes, having baked for 25 minutes, it may look like cake but, as any baker knows, it is still partly goop inside. If a toothpick (our grandmothers used a broom straw) is inserted into the middle of the “cake” and then removed, it does not come out clean. In the last few minutes of the process, the goop in the middle becomes cake. If left a few minutes too long in the oven, the cake will begin to burn on the bottom. Project Cake follows a J-shaped path to completion much like Figure 1-3.

There are many projects that are similar to cake—the development of computer software, and many chemical engineering projects, for instance. In these cases the PM's job begins with great attention to having all the correct project resources at hand or guaranteed to be available when needed. Once the “baking” process is underway—the integration of various sets of code or chemicals—one can usually not add missing ingredients. As the process continues, the PM must concentrate on determining when the project is complete—“done” in the case of cake, or a fully debugged program in the case of software.

In later chapters, we will also see the importance of the shape of the project's life cycle on how management allocates resources or reacts to potential delays in a project. Management does not need to know the precise shape of the life cycle, but merely whether its completion phase is concave (Figure 1-2) or convex (Figure 1-3) to the baseline.

There are two different paths (life cycles) along which projects progress from start to completion. One is S-shaped, and the other is J-shaped. It is an important distinction because identifying the different life cycles helps the PM to focus attention on appropriate matters to ensure successful project completion.

1.5 SELECTING PROJECTS TO MEET ORGANIZATIONAL OBJECTIVES

The accomplishment of important tasks and goals in organizations today is being achieved increasingly through the use of projects. A new kind of organization has emerged recently to deal with the accelerating growth in the number of multiple, simultaneously ongoing, and often interrelated projects in organizations. This project-oriented organization, often called “enterprise project management” (Levine, 1998), “management by projects” (Boznak, 1996), and similar names, was created to tie projects more closely to the organization's goals and strategy and to integrate and centralize management methods for the growing number of ongoing projects. Given that the organization has an appropriate mission statement and strategy, selected projects should be consistent with the strategic goals of the organization. In what follows, we first discuss a variety of common project selection methods. We then describe the process of strategically selecting the best set of projects for implementation, called the Project Portfolio Process.

Project selection is the process of evaluating individual projects or groups of projects and then choosing to implement a set of them so that the objectives of the parent organization are achieved. Before a project begins its life cycle, it must have been selected for funding by the parent organization. Whether the project was proposed by someone within the organization or an outside client, it is subject to approval by a more or less formal selection process. Often conducted by a committee of senior managers, the major function of the selection process is to ensure that several conditions are considered before a commitment is made to undertake any project. These conditions vary widely from firm to firm, but several are quite common: (1) Is the project potentially profitable? Does it have a chance of meeting our return-on-investment hurdle rate? (2) Is the project required by law or the rules of an industrial association; i.e., a “mandate?” (3) Does the firm have, or can it easily acquire, the knowledge and skills to carry out the project successfully? (4) Does the project involve building competencies that are considered consistent with our firm's strategic plan? (5) Does the organization currently have the capacity to carry out the project on its proposed schedule? (6) In the case of R&D projects, if the project is technically successful, does it meet all requirements to make it economically successful? This list could be greatly extended.

The selection process is often complete before a PM is appointed to the project. Why, then, should the PM be concerned? Quite simply, the PM should know exactly why the organization selected the specific project because this sheds considerable light on what the project (and hence the PM) is expected to accomplish, from senior management's point of view, with the project. The project may have been selected because it appeared to be profitable, or was a way of entering a new area of business, or a way of building a reputation of competency with a new client or in a new market. This knowledge can be very helpful to the PM by indicating senior management's goals for the project, which will point to the desirability of some trade-offs and the undesirability of Trade-Offs others.

![]()

There are many different methods for selecting projects, but they may be grouped into two fundamental types, nonnumeric and numeric. The former does not use numbers for evaluation; the latter does. At this point it is important to note that many firms select projects before a detailed project plan has been developed. Clearly, if the potential project's scope, budget, and due dates have not been determined, it will be quite impossible to derive a reasonably accurate estimate of the project's success. Rough estimations may have to suffice in such cases, but specific plans should be developed prior to final project selection. Obviously, mandated projects are an exception. For mandates, budget estimates do not matter but scope and due dates are still important. Mandates must be selected. We will deal further with the selection problem when we consider the Project Management Office in Chapter 2.

Nonnumeric Selection Methods

The Sacred Cow At times, the organization's Chief Executive Officer (CEO) or other senior executive either formally or casually suggests a potential product or service that the organization might offer to its customers. The suggestion often starts, “You know, I was thinking that we might . . .” and concludes with “. . . Take a look at it and see if it looks sensible. If not, we'll drop the whole thing.”

Whatever the selection process, the aforementioned project will be approved. It becomes a “Sacred Cow” and will be shown to be technically, if not economically, feasible. This may seem irrational to new students of project management, but such a judgment ignores senior management's intelligence and valuable years of experience—as well as the subordinate's desire for long-run employment. It also overlooks the value of support from the top of the organization, a condition that is necessary for project success (Green, 1995).

The Operating/Competitive Necessity This method selects any project that is necessary for continued operation of a group, facility, or the firm itself. A “mandated” project obviously must be selected. If the answer to the “Is it necessary . . .?” question is “yes,” and if we wish to continue using the facility or system to stay in business, the project is selected. The Investment Committee of a large manufacturing company started to debate the advisability of purchasing and installing pumps to remove 18 inches of flood water from the floor of a small, but critical production facility. The debate stopped immediately when one officer pointed out that without the pumps the firm was out of business.

The same questions can be directed toward the maintenance of a competitive position. Some years ago, General Electric almost decided to sell a facility that manufactured the large mercury vapor light bulbs used for streetlights and lighting large parking lots. The lighting industry had considerable excess capacity for this type of bulb and the resulting depressed prices meant they could not be sold profitably. GE, however, felt that if they dropped these bulbs from their line of lighting products, they might lose a significant portion of all light bulb sales to municipalities. The profits from such sales were far in excess of the losses on the mercury vapor bulbs.

Comparative Benefits Many organizations have to select from a list of projects that are complex, difficult to assess, and often noncomparable, e.g., United Way organizations and R&D organizations. Such institutions often appoint a selection committee made up of knowledgeable individuals. Each person is asked to arrange a set of potential projects into a rank-ordered set. Typically, each individual judge may use whatever criteria he or she wishes to evaluate projects. Some may use carefully determined technical criteria, but others may try to estimate the project's probable impact on the ability of the organization to meet its goals. While the use of various criteria by different judges may trouble some, it results from a purposeful attempt to get as broad a set of evaluations as possible.

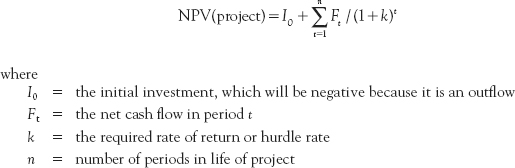

Rank-ordering a small number of projects is not inherently difficult, but when the number of projects exceeds 15 or 20, the difficulty of ordering the group rises rapidly. A Q-sort* is a convenient way to handle the task. First, separate the projects into three subsets, “good,” “fair,” and “poor,” using whatever criteria you have chosen—or been instructed to use. If there are more than seven or eight members in any one classification, divide the group into two subsets, for instance, “good-plus” and “good-minus.” Continue subdividing until no set has more than seven or eight members (see Figure 1-4). Now, rank-order the items in each subset. Arrange the subsets in order of rank, and the entire list will be in order.

The committee can make a composite ranking from the individual lists any way it chooses. One way would be to number the items on each individual list in order of rank, and then add the ranks given to each project by each of the judges. Projects may then be approved in the order of their composite ranks, at least until the organization runs out of available funds.

Numeric Selection Methods

Financial Assessment Methods Most firms select projects on the basis of their expected economic value to the firm. Although there are many economic assessment methods available—payback period, average annual rate of return, internal rate of return, and so on—we will describe here two of the most widely used methods: payback period and discounted cash flow.*

![]()

The payback period for a project is the initial fixed investment in the project divided by the estimated annual net cash inflows from the project (which include the cash inflows from depreciation of the investment). The ratio of these quantities is the number of years required for the project to return its initial investment. Because of this perspective, the payback period is often considered a surrogate measure of risk to the firm: the longer the payback period, the greater the risk. To illustrate, if a project requires an investment of $100,000 and is expected to return a net cash inflow of $25,000 each year, then the payback period is simply 100,000/25,000 = 4 years, assuming the $25,000 annual inflow continues at least 4 years. Although this is a popular financial assessment method, it ignores the time value of money as well as any returns beyond the payback period. For these reasons, it is not recommended as a project selection method, though it is valuable for cash budgeting. Of the financial assessment methods, the discounted cash flow method discussed next is recommended instead.

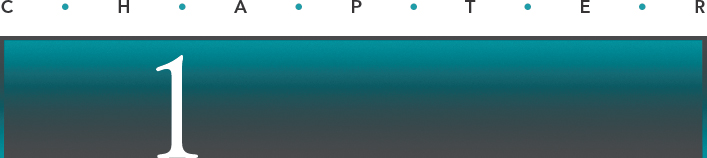

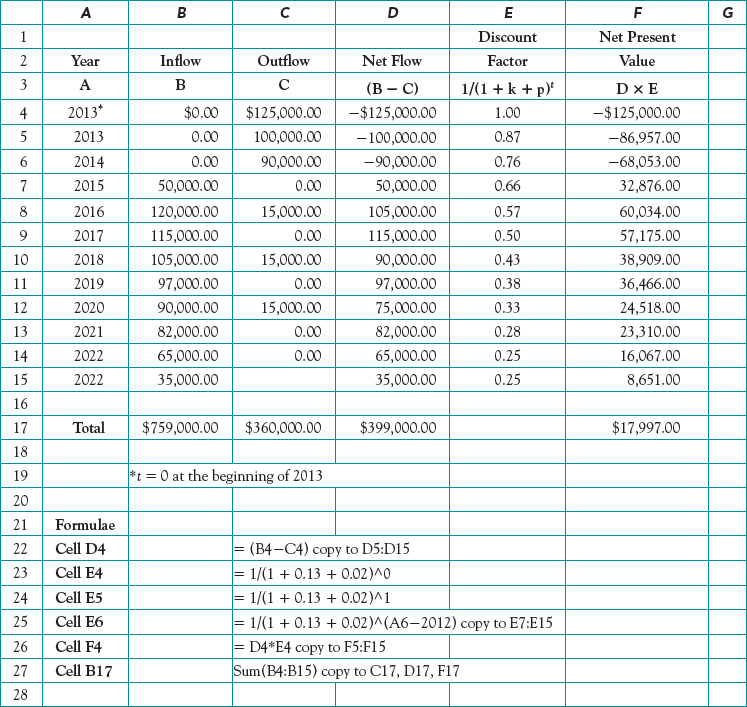

The discounted cash flow method considers the time value of money, the inflation rate, and the firm's return-on-investment (ROI) hurdle rate for projects. The annual cash inflows and outflows are collected and discounted to their net present value (NPV) using the organization's required rate of return (a.k.a. the hurdle rate or cutoff rate).

If one wishes to include the potential effects of inflation or deflation in the calculation, it is quite easily done. The discounting term, (1 + k)t, simply becomes (1 + k + pt)t, where pt is the estimated rate of inflation or deflation for period t. If the required rate of return is 10 percent and we expect the rate of inflation will be 3 percent, then the discount factor becomes (1 + .10 + .03)t = (1.13)t for that period.

In the early years of a project when outflows usually exceed inflows, the NPV of the project for those years will be negative. If the project becomes profitable, inflows become larger than outflows and the NPV for those later years will be positive. If we calculate the present value of the net cash flows for all years, we have the NPV of the project. If this sum is positive, the project may be accepted because it earns more than the required rate of return. The following boxed example illustrates these calculations. Although the example employs a spreadsheet for clarity and convenience in the analysis, we have chosen to illustrate the calculations using the NPV formula directly rather than using a spreadsheet function such as NPV (in Excel®) so the reader can better see what is happening. Once the reader understands how this works, we suggest using the simpler spreadsheet functions to speed up the process.

PsychoCeramic Sciences, Inc.*

PsychoCeramic Sciences, Inc. (PSI) is a large producer of cracked pots and other cracked items. The firm is considering the installation of a new manufacturing line that will, it is hoped, allow more precise quality control on the size, shape, and location of the cracks in its pots as well as in vases designed to hold artificial flowers.

The plant engineering department has submitted a project proposal that estimates the following investment requirements: an initial investment of $125,000 to be paid up-front to the Pocketa-Pocketa Machine Corporation, an additional investment of $100,000 to install the machines, and another $90,000 to add new material handling systems and integrate the new equipment into the overall production system. Delivery and installation is estimated to take 1 year, and integrating the entire system should require an additional year. Thereafter, the engineers predict that scheduled machine overhauls will require further expenditures of about $15,000 every second year, beginning in the fourth year. They will not, however, overhaul the machinery in the last year of its life.

The project schedule calls for the line to begin production in the third year, and to be up-to-speed by the end of that year. Projected manufacturing cost savings and added profits resulting from higher quality are estimated to be $50,000 in the first year of operation and are expected to peak at $120,000 in the second year of operation, and then to follow the gradually declining pattern shown in Table A.

Project life is expected to be 10 years from project inception, at which time the proposed system will be obsolete and will have to be replaced. It is estimated that the machinery will have a salvage value of $35,000. PSI has a 13 percent hurdle rate for capital investments and expects the rate of inflation to be about 2 percent per year over the life of the project. Assuming that the initial expenditure occurs at the beginning of the year and that all other receipts and expenditures occur as lump sums at the end of the year, we can prepare the Net Present Value analysis for the project as shown in Table A.

Because the first cash flow of − $125,000 occurs at the beginning of the first period, there is no need to discount it as it is already in present value terms. The remaining cash flows are assumed to occur at the end of their respective periods. For example, the $115,000 cash flow associated with 2017 is assumed to occur at the end of the fifth period. According to the results, the Net Present Value of the project is positive and, thus, the project can be accepted. (The project would have been rejected if the hurdle rate had been 15 percent or if the inflation rate was 4 percent, either one resulting in a discount rate of 17 percent.)

Perhaps the most difficult aspect related to the proper use of discounted cash flow is determining the appropriate discount rate to use. While this determination is made by senior management, it has a major impact on project selection, and therefore, on the life of the PM. For most projects the hurdle rate selected is the organization's cost of capital, though it is often arbitrarily set too high as a general allowance for risk. In the case of particularly risky projects, a higher hurdle rate may be justified, but it is not a good general practice. If a project is competing for funds with alternative investments, the hurdle rate may be the opportunity cost of capital, that is, the rate of return the firm must forego if it invests in the project instead of making an alternative investment. Another common, but misguided practice is to set the hurdle rate high as an allowance for resource cost increases. Neither risk nor inflation should be treated so casually. Specific corrections for each should be made if the firm's management feels it is required. We recommend strongly a careful risk analysis, which we will discuss in further detail throughout this book.

![]()

Because the present value of future returns decreases as the discount rate rises, a high hurdle rate biases the analysis strongly in favor of short-run projects. For example, given a rate of 20 percent, a dollar 10 years from now has a present value of only $.16, (1/1.20)10 = 0.16. The critical feature of long-run projects is that costs associated with them are spent early in the project and have high present values while revenues are delayed for several years and have low present values.

This effect may have far-reaching implications. The high interest rates during the 1970s and 1980s, and again in the 2000s, forced many firms to focus on short-run projects. The resulting disregard for long-term technological advancement led to a deterioration in the ability of some United States firms to compete in world markets (Hayes and Abernathy, 1980).

The discounted cash flow methods of calculation are simple and straightforward. Like the other financial assessment methods, it has a serious defect. First, it ignores all nonmonetary factors except risk. Second, because of the nature of discounting, all the discounted methods bias the selection system by favoring short-run projects. Let us now examine a selection method that goes beyond assessing only financial profitability.

Financial Options and Opportunity Costs A more recent approach to project selection employs financial analysis that recognizes the value of positioning the organization to capitalize on future opportunities. It is based on the financial options approach to valuing prospective capital investment opportunities. Through a financial option an organization or individual acquires the right to do something but is not required to exercise that right. For example, you may be familiar with stock options. When a person or organization purchases a stock option, they acquire the right to purchase a specific number of shares of a particular stock at a specified price within a specified time frame. If the market price of the stock moves above the specified option price within the specified time frame, the entity holding the option can exercise its right and thereby purchase the stock below the fair market price. If the market price of the stock remains below the specified option price, the entity can choose not to exercise its right to buy the stock.

To illustrate the analogy of financial options to project selection, consider a young biotech firm that is ready to begin clinical trials to test a new pharmaceutical product in humans. A key issue the company has to address is how to produce the drug both now in the low volumes needed for the clinical trials and in the mass quantities that will be needed in the future should the new drug succeed in the clinical trial phase. Its options for producing the drug in low volumes for the clinical trials are to invest in an in-house pilot plant or to immediately license the drug to another company. If it invests in an in-house pilot plan, it then has two future options for mass producing the drug: (1) invest in a commercial scale plant or (2) license the manufacturing rights. In effect then, investing now in the pilot plant provides the pharmaceutical company with the option of building a commercial scale plant in the future, an option it would not have if it chooses to license the drug right from the start. Thus by building the in-house pilot plant the pharmaceutical company is in a sense acquiring the right to build a commercial plant in the future. While beyond the scope of this book, we point out to the reader that in addition to the traditional approaches to project selection, the decision to build the pilot plant can also be analyzed using valuation techniques from financial options theory. In this case the value of having the option to build a commercial plant can be estimated.

In addition to considering the value of future opportunities a project may provide, the cost of not doing a project should also be considered. This approach to project selection is based on the well-known economic concept of “opportunity cost.” Consider the problem of making an investment in one of only two projects. An investment in Project A will force us to forgo investing in Project B, and vice versa. If the return on A is 12 percent, making an investment in B will have an opportunity cost of 12 percent, the cost of the opportunity forgone. If the return on B is greater than 12 percent, it may be preferred over selecting Project A.

The same selection principle can be applied to timing the investment in a given project. R&D projects or projects involving the adoption of new technologies, for example, have values that may vary considerably with time. It is common for the passage of time to reduce uncertainties involved in both technological and commercial projects. The value of investing now may be higher (or lower) than investing later. If a project is delayed, the values of its costs and revenues at a later period should be discounted to their present value when compared to an investment not delayed.

Occasionally, organizations will approve projects that are forecast to lose money when fully costed and sometimes even when only direct costed. Such decisions by upper management are not necessarily foolish because there may be other, more important reasons for proceeding with a project, such as to:

- Acquire knowledge concerning a specific or new technology

- Get the organization's “foot in the door”

- Obtain the parts, service, or maintenance portion of the work

- Allow them to bid on a lucrative, follow-on contract

- Improve their competitive position

- Broaden a product line or line of business

Of course, such decisions are expected to lose money in the short term only. Over the longer term they are expected to bring extra profits to the organization. It should be understood that “lowball” or “buy-in” bids (bidding low with the intent of cutting corners on work and material, or forcing subsequent contract changes) are unethical practices, PMBOK Guide violate the PMI Code of Ethics for Project Managers (see PMBOK, p. 2, 2013), and are clearly dishonest.

![]()

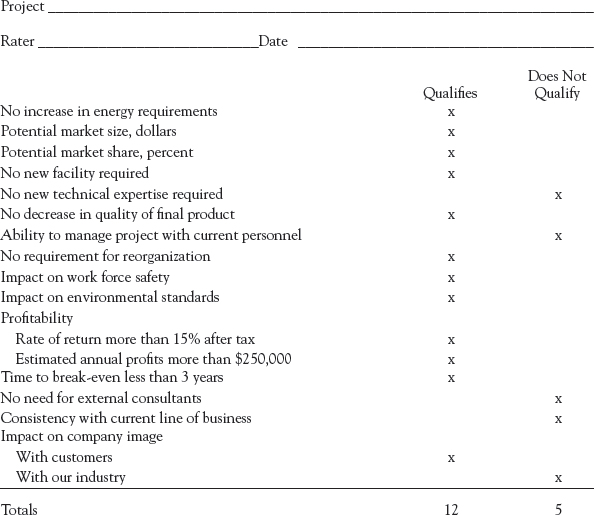

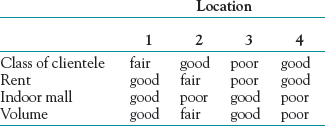

Scoring Methods Scoring methods were developed to overcome some of the disadvantages of the simple financial profitability methods, especially their focus on a single criterion. The simplest scoring approach, the unweighted 0–1 factor method, lists multiple criteria of significant interest to management. Given a list of the organization's goals, a selection committee, usually senior managers familiar with both the organization's criteria and potential project portfolio, check off, for each project, which of the criteria would be satisfied; for example, see Figure 1-5. Those projects that exceed a certain number of check-marks may be selected for funding.

Figure 1-5 A sample project selection form, an unweighted 0–1 scoring model.

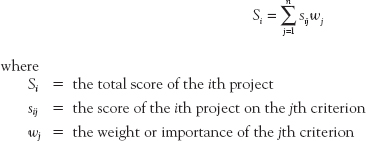

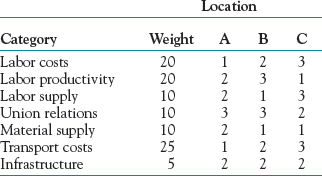

All the criteria, however, may not be equally important and the various projects may satisfy each criterion to different degrees. To correct for these drawbacks, the weighted factor scoring method was developed. In this method, a number of criteria, n, are considered for evaluating each project, and their relative importance weights, wj, are estimated. The sum of the weights over all the j criteria is usually set arbitrarily at 1.00, though this is not mandatory. It is helpful to limit the criteria to just the major factors and not include criteria that are only marginal to the decision, such as representing only 2 or 3 percent importance. A rule of thumb might be to keep n less than eight factors because the higher weights, say 20 percent or more, tend to force the smaller weights to be insignificant. The importance weights, wj, can be determined in any of a number of ways: a particular individual's subjective belief, available objective factors such as surveys or reports, group composite beliefs such as simple averaging among the group members, and so on.

In addition, a score, sij, must be determined for how well each project i satisfies each criterion j. Each score is multiplied by its category weight, and the set of scores is summed to give the total weighted score, Si = Σjsijwj for each project, i, from which the best project is then selected. Typically, a 5-point scale is used to ascertain these scores, though 3-, 7-, and even 9-point scales are sometimes used. The top score, such as 5, is reserved for excellent performance on that criterion such as a return on investment (ROI) of 50 percent or more, or a reliability rating of “superior.” The bottom score of 1 is for “poor performance,” such as an ROI of 5 percent or less, or a reliability rating of “poor.” The middle score of 3 is usually for average or nominal performance (e.g., 15–20% ROI), and 4 is “above average” (21–49% ROI) while 2 is “below average” (6–14% ROI). Notice that the bottom score, 1, on one category may be offset by very high scores on other categories. Any condition that is so bad that it makes a project unacceptable, irrespective of how good it may be on other criteria, is a constraint. If a project violates a constraint, it is removed from the set and not scored.

Note two characteristics in these descriptions. First, the categories for each scale need not be in equal intervals—though they should correspond to the subjective beliefs about what constitutes excellent, below average, and so on. Second, the five-point scales can be based on either quantitative or qualitative data, thus allowing the inclusion of financial and other “hard” data (cash flows, net present value, market share growth, costs) as well as “soft” subjective data (fit with the organization's goals, personal preferences, attractiveness, comfort). And again, the soft data also need not be of equal intervals. For example, “superior” may rate a 5 but “OK” may rate only a 2.

The general mathematical form of the weighted factor scoring method is

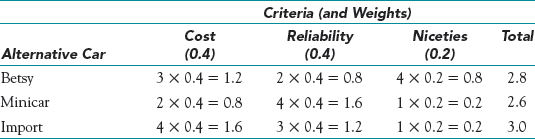

Using a Weighted Scoring Model to Select Wheels

As a college student, you now find that you need to purchase a car in order to get to your new part-time job and around town more quickly. This is not going to be your “forever” car, and your income is limited; basically, you need reliable wheels. You have two primary criteria of equal importance, cost and reliability. You have a limited budget and would like to spend no more than $4,200 on the car. In terms of reliability, you can't afford to have the car break down on your way to work, or for that matter, cost a lot to repair. Beyond these two major criteria, you consider everything else a “nicety” such as comfort, heat and air, appearance, handling, and so on. Such niceties you consider only half as important as either cost or reliability. Table B shows a set of scales you created for your three criteria, converted into quantitative scores.

Table B: Criteria Scales and Equivalent Scores

You have identified three possible cars to purchase. Your sorority sister is graduating this semester and is looking to replace “Betsy,” her nice subcompact. She was going to trade it in but would let you have it for $3,400, a fair deal, except the auto magazines rate its reliability as below average. You have also seen an ad in the paper for a more reliable Minicar for $4,100 but the ad indicates it needs some body work. Last, you tore off a phone number from a campus poster for an old Japanese Import for only $2,900.

In Table C, you have scored each of the cars on each of the criteria, calculated their weighted scores, and summed them to get a total. The weights for the criteria were obtained from the following logic: If Y is the importance weight for Cost, then Y is also the importance for Reliability and ½Y is the importance for Niceties. This results in the formula

![]()

Thus, Cost has 0.4 importance weight, as does Reliability, and Niceties has 0.2 importance.

Table C: Weighted Total Scores for Each Car

Based on this assessment, it appears that the Import with a total weighted score of 3.0 may best satisfy your need for basic transportation. As shown in Table D, spreadsheets are a particularly useful tool for comparing options using a weighted scoring model.

Table D: Creating a Weighted Scoring Model in a Spreadsheet

Project selection is an inherently risky process. Throughout this section we have treated risk by “making allowance” for it. Managing and analyzing risk can be handled in a more straightforward manner. By estimating the highest, lowest, and most likely values that costs, revenues, and other relevant variables may have, and by making some other assumptions about the world, we can estimate outcomes for the projects among which we are trying to make selections. This is accomplished by simulating project outcomes. In Chapter 4, Section 4.5, we will demonstrate how to do this using Crystal Ball® (CB) on a sample selection problem.

The PM should understand why a project is selected for funding so that the project can be managed to optimize its advantages and achieve its objectives. There are two types of project selection methods: numeric and nonnumeric. Both have their advantages. Of the numeric methods, there are two subtypes—methods that assess the profits associated with a project and more general methods that measure nonmonetary advantages in addition to the monetary pluses. Of the financial methods, the discounted cash flow is best. In our judgment, however, the weighted scoring method is the most useful.

1.6 THE PROJECT PORTFOLIO PROCESS

![]()

The Project Portfolio Process (PPP) attempts to link the organization's projects directly to the goals and strategy of the organization. This occurs not only in the project's initiation and planning phases, but also throughout the life cycle of the projects as they are managed and eventually brought to completion. This topic is compared to project PMBOK Guide and program management in PMBOK's Chapter 1: Introduction. Thus, the PPP is also a means for monitoring and controlling the organization's strategic projects, as will be reiterated in Chapter 7: Monitoring and Controlling the Project. On occasion this will mean shutting down projects prior to their completion because their risks have become excessive, their costs have escalated beyond their expected benefits, another (or a new) Risk project does a better job of supporting the goals, or any of a variety of similar reasons. The steps in this process generally follow those described in Longman, Sandahl, and Speir (1999) and Englund and Graham (1999).

![]()

Step 1: Establish a Project Council

The main purpose of the Project Council is to establish and articulate a strategic direction for projects. The Council will also be responsible for allocating funds to those projects that support the organization's goals and controlling the allocation of resources and skills to the projects. In addition to senior management, other appropriate members of the Project Council include: project managers of major projects; the head of the Project Management Office (if one exists, and the Council can also be housed in the PMO); particularly relevant general managers, that is, those who can identify key opportunities and risks facing the organization; and finally, those who can derail the progress of the PPP later in the process.

Step 2: Identify Project Categories and Criteria

In this step, various project categories are identified so the mix of projects funded by the organization will be spread appropriately across those areas making major contributions to the organization's goals. In addition, within each category criteria are established to discriminate between very good and even better projects using the weighted scoring model previously discussed. The criteria are also weighted to reflect their relative importance.

The first task in this step is to list the goals of each existing and proposed project—that is, the mission, or purpose, of each project. Relating these to the organization's goals and strategies should allow the Council to identify a variety of categories that are important to achieving the organization's goals. One way to position many of the projects (particularly product/service development projects) is in terms of the extent of product and process changes. Wheelwright and Clark (1992) have developed a matrix called the aggregate project plan illustrating these changes, as shown in Figure 1-6. Based on the extent of product change and process change, they identified four separate cat-Best Practice egories of projects:

![]()

- Derivative projects These are projects with objectives or deliverables that are only incrementally different in both product and process from existing offerings. They are often meant to replace current offerings or add an extension to current offerings (lower priced version, upscale version).

- Platform projects The planned outputs of these projects represent major departures from existing offerings in terms of either the product/service itself or the process used to make and deliver it, or both. As such, they become “platforms” for the next generation of organizational offerings, such as a new model of automobile or a new type of insurance plan. They form the basis for follow-on derivative projects that attempt to extend the platform in various dimensions.

- Breakthrough projects Breakthrough projects typically involve a newer technology than platform projects. It may be a “disruptive” technology that is known to the industry or something proprietary that the organization has been developing over time. Examples here include the use of fiber-optic cables for data transmission, cash-balance pension plans, and hybrid gasoline-electric automobiles.

- R&D projects These projects are “blue-sky,” visionary endeavors, oriented toward using newly developed technologies, or existing technologies in a new manner. They may also be for acquiring new knowledge, or developing new technologies themselves.

The size of the projects plotted on the array indicates the size/resource needs of the project, and the shape may indicate another aspect of the project (for example, internal/external, long/medium/short term, or whatever aspect needs to be shown). The numbers indicate the order, or time frame, in which the projects are to be (or were) implemented, separated by category, if desired.

The aggregate project plan can be used to:

- View the mix of projects within each illustrated aspect (shape)

- Analyze and adjust the mix of projects within each category or aspect

- Assess the resource demands on the organization, indicated by the size, timing, and number of projects shown

- Identify and adjust the gaps in the categories, aspects, sizes, and timing of the projects

- Identify potential career paths for developing project managers, such as team members of a derivative project, then team member of a platform project, manager of a derivative project, member of a breakthrough project, and so on

Step 3: Collect Project Data

For each existing and proposed project, assemble the data appropriate to that category's criteria. Include the timing, both date and duration, for expected benefits and resource needs. Use the project plan, a schedule of project activities, past experience, expert opinion, whatever is available to get a good estimate of these data. If the project is new, you may want to fund only enough work on the project to verify the assumptions.

Next, use the criteria score limits, or constraints as described in our discussions of scoring models, to screen out the weaker projects. For example, have costs on existing projects escalated beyond the project's expected benefits? Has the benefit of a project lessened because the organization's goals have changed? Also, screen in any projects that do not require deliberation, such as projects mandated by regulations or laws, projects that are competitive or operating necessities (described above), projects required for environmental or personnel reasons, and so on. The fewer projects that need to be compared and analyzed, the easier the work of the Council.

When we discussed financial models and scoring models, we urged the use of multiple criteria when selecting projects. ROI on a project may be lower than the firm's cut-off rate, or even negative, but the project may be a platform for follow-on projects that have very high benefits for the firm. Wheatly (2009) also warns against the use of a single criterion, commonly the return on investment (ROI), to evaluate projects. A project aimed at boosting employee satisfaction will often yield improvements in output, quality, costs, and other such factors. For example, Mindtree, of Bangalore, India, measures benefits on five dimensions; revenue, profit, customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and intellectual capital created—in sum, “Have we become a better company?”

Step 4: Assess Resource Availability

Next, assess the availability of both internal and external resources, by type, department, and timing. Note that labor availability should be estimated conservatively. Timing is particularly important, since project resource needs by type typically vary up to 100 percent over the life cycle of projects. Needing a normally plentiful resource at the same moment it is fully utilized elsewhere may doom an otherwise promising project. Eventually, the Council will be trying to balance aggregate project resource needs over future periods with resource availabilities, so timing is as important as the amount of maximum demand and availability. Many managers insist on trying to schedule resource usage as closely as possible to system capacity. This is almost certain to produce a catastrophe (see Chapter 6, Section 6.3, subsection on Resource Loading/Leveling and Uncertainty).

Step 5: Reduce the Project and Criteria Set

In this step, multiple screens are employed to reduce the number of competing projects. As noted earlier, the first screen is each project's support of the organization's goals. Other possible screens might be criteria such as:

- Whether the required competence exists in the organization

- Whether there is a market for the offering

- The likely profitability of the offering

- How risky the project is

- If there is a potential partner to help with the project

- If the right resources are available at the right times

- If the project is a good technological/knowledge fit with the organization

- If the project uses the organization's strengths, or depends on its weaknesses

- If the project is synergistic with other important projects

- If the project is dominated by another existing or proposed project

- If the project has slipped in its desirability since the last evaluation

Step 6: Prioritize the Projects within Categories

Apply the scores and criterion weights to rank the projects within each category. It is acceptable to hold some hard-to-measure criteria out for subjective evaluation, such as riskiness, or development of new knowledge. Subjective evaluations can be translated from verbal to numeric terms easily by the Delphi* Method, pairwise comparisons, or other methods.

It is also possible at this time for the Council to summarize the “returns” from the projects to the organization. This, however, should be done by category, not for each project individually, since different projects are offering different packages of benefits that are not comparable. For example, R&D projects will not have the expected monetary return of derivative projects; yet it would be foolish to eliminate them simply because they do not measure up on this (irrelevant, for this category) criterion.

Step 7: Select the Projects to Be Funded and Held in Reserve

The first task in this step is to determine the mix of projects across the various categories (and aspects, if used) and time periods. Next, be sure to leave some percent (the common 10–15% is often insufficient) of the organization's resource capacity free for new opportunities, crises in existing projects, errors in estimates, and so on. Then allocate the categorized projects in rank order to the categories according to the mix desired. It is usually good practice to include some speculative projects in each category to allow future options, knowledge improvement, additional experience in new areas, and so on. The focus should be on committing to fewer projects but with sufficient funding to allow project completion. Document why late projects were delayed and why any were defended.

Step 8: Implement the Process

The first task in this final step is to make the results of the PPP widely known, including the documented reasons for project cancellations, deferrals, and nonselection as was mentioned earlier. Top management must now make their commitment to this project portfolio process totally clear by supporting the process and its results. This may require a PPP champion near the top of the organization. As project proposers come to understand and appreciate the workings and importance of the PPP, their proposals will more closely fit the profile of the kinds of projects the organization wishes to fund. As this happens, it is important to note that the Council will have to concern itself with the reliability and accuracy of proposals competing for limited funds. Senior management must fully fund the selected projects. It is unethical and inappropriate for senior management to undermine PPP and the Council as well as strategically important projects by playing a game of arbitrarily cutting X percent from project budgets. It is equally unethical and inappropriate to pad potential project budgets on the expectation that they will be arbitrarily cut.

Finally, the process must be repeated on a regular basis. The Council should determine the frequency, which to some extent will depend on the speed of change within the organization's industry. For some industries, quarterly analysis may be best, while in slow-moving industries yearly may be fine.

In an article on competitive intelligence, Gale (2008b) reports that Cisco Systems Inc. constantly tracks industry trends, competitors, the stock market, and end users to stay ahead of their competition and to know which potential projects to fund. Pharmaceutical companies are equally interested in knowing which projects to drop if competitors are too far ahead of them, thereby saving millions of dollars in development and testing costs.

Hildebrand (2008) suggests giving another task to the Project Council (or the PMO): formulating a change-response strategy so the company can modify the project portfolio quickly when unexpected events occur. Although significant events seem to occur without warning, most, but not all, significant events follow a stream of lesser events or cues that might have been identified through standard risk identification techniques. Advanced preparation to define the types of data, control, and execution resources needed to make wise decisions in the midst of a crisis will pay substantial dividends. Practice exercises or simulations can enhance the firm's ability for effective crisis response. If project staffs understand how the portfolio was originally built and why specific projects were selected or dropped, they will be more likely to understand what a crisis implies for the portfolio and to support crisis-related decisions.

Projects are often subdivisions of major programs. Long-run success is determined by the organization's portfolio of projects. Classified by the extent of innovation in product and process, there are four types of projects: derivative, breakthrough, platform, and R & D projects. The actual mix of projects is a direct expression of the organization's competitive strategy. A proper mix of project categories can help ensure its long-run competitive position. It is important for the Project Council or PMO to preplan project portfolio adjustments to respond to significant changes in the state of competition and other industrial crises.

1.7 THE MATERIALS IN THIS TEXT