6.3. Implementing least privilege

The ultimate goal of implementing least privilege is reducing the permissions of user and service accounts to the absolute minimum required. Doing this can be difficult and requires considerable planning. This section focuses on this goal from four perspectives:

Separating Windows and database administrator privileges

Reducing the permissions of the SQL Server service accounts

Using proxies and credentials to limit the effective permissions of SQL Server Agent jobs

Using role-based security to simplify and tighten permissions management

Let's begin with a contentious issue: separating and limiting the permissions of DBAs and Windows administrators.

6.3.1. Windows and DBA privilege separation

Removing the local admin group membership from a DBA is almost always likely to provoke a strong response. Most DBAs take it as a personal insult, akin to not being trusted with basic tasks. When questioned about whether Windows administrators should be SQL Server sysadmins, the response is typically as passionate, with the DBAs usually unaware of their own contradiction!

In most cases, DBAs don't need to be local administrators to do their job. Not only that, they shouldn't be. Equally true, Windows administrators shouldn't be SQL Server sysadmins.

Separation of powers in this manner is a basic security concept, but probably the most commonly abused one. The reasons for this are many and varied. First, in previous versions of SQL Server (2005 and earlier) the BUILTINAdministrators group is automatically added to the SQL Server sysadmins server role, making Windows administrators effectively DBAs by default. Second, DBAs are often tasked (particularly in smaller environments) with being the Windows administrator as well as the DBA. And third, to avoid dealing with Windows administrators to get things done, some DBAs will come up with various reasons why they should be local administrators, often bamboozling management into submission.

Why separate permissions? Well, a Windows administrator with very little DBA experience could accidentally delete critical data or entire databases without realizing it. Or a DBA, after accessing sensitive data, could cover his or her tracks by deleting audit files from the operating system.

There are obviously many more examples, all of which require separation of powers to protect against both deliberate and accidental destructive actions. As you saw in chapter 4, SQL Server 2008 helps out in this regard by not including the BUILTIN Administrators group in the sysadmin server role.

Continuing the theme of least privilege, the SQL Server service accounts shouldn't be members of the local administrators group.

6.3.2. SQL Server service account permissions

A common SQL Server myth is that the accounts used by the SQL Server services need to be members of the local administrators group. They don't, and in fact shouldn't be. During installation, SQL Server will assign the necessary file, registry, and system permissions to the accounts nominated for the services.

The need to avoid using local administrator accounts (or the localsystem account) is based on the possibility of the server being compromised and used to run OS-level commands using tools such as xp_cmdshell, which is disabled by default. While other protections should be in place to prevent such attacks, locking down all possible avenues of attack is best practice, and using nonprivileged service accounts is an important part of this process.

As you learned in chapter 4, separate accounts should be used for each SQL Server service to enable the most granular security permissions. Finally, should the security account be changed postinstallation, the SQL Server Configuration Manager tool should be used, rather than a direct assignment using the Control Panel services applet. When you use the Configuration Manager tool, SQL Server will assign the new account the necessary permissions as per the initial installation.

Like all items in this section, configuring nonadministrator accounts for SQL Server services is about assigning the minimal set of privileges possible. This is an important security concept not only for service accounts but for all aspects of SQL Server, including SQL Server Agent jobs.

6.3.3. SQL Server Agent job permissions

A common requirement for SQL Server deployments is for SQL Server Agent jobs (covered in more detail in chapter 14) to access resources outside of SQL Server. Among other tasks, such jobs are typically used for executing batch files and Integration Services packages.

To enable the minimum set of permissions to be in place, SQL Server Agent enables job steps to run under the security context of a proxy. One or more proxies are created as required, each of which uses a stored credential. The combination of credentials and proxies enables job steps to run using a Windows account whose permissions can be tailored (minimized) for the needs of the Agent job step.

In highlighting how proxies and credentials are used, let's walk through a simple example of setting minimal permissions for a SQL Agent job that executes an Integration Services package. We'll begin this process by creating a credential.

Credentials

When you create a SQL Agent proxy, one of the steps is to specify which credential the proxy will use. We'll see that shortly. It follows that before creating the proxy, the credential should be created. Figure 6.5 shows an example of the creation of a credential in SQL Server Management Studio. You access this dialog by right-clicking Credentials under Security and choosing New Credential.

Figure 6.5. Create a credential in order to define the security context of a SQL Agent proxy.

In figure 6.5, we've specified the SQL Proxy-SalesSSISIm account, whose permissions[] have been reduced to the minimum required for executing our Integration Services package. For example, we've granted the account read permissions to a directory containing files to import into the database. In addition to setting permissions at a domain/server level, we'd add this credential as a SQL login with the appropriate database permissions.

[] The credential account must also have the "Log on as a batch job" permission on SQL Server.

After creating the credential, we can now create the proxy.

Proxies

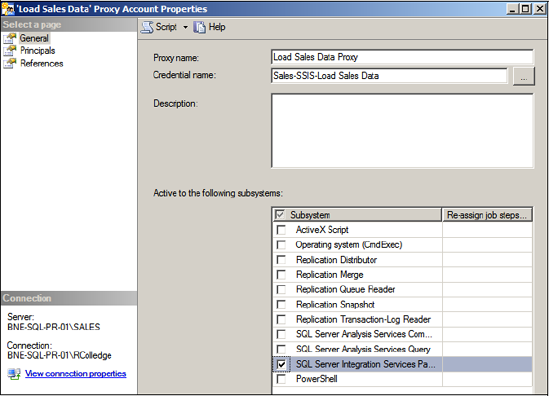

You create a SQL Agent proxy in SQL Server Management Studio by right-clicking Proxies under SQL Server Agent and choosing New Proxy. The resulting screen, as shown in figure 6.6, allows you to specify the details of the proxy, including the name, the credential to use, and which subsystems the proxy can access. In our case, we'll use the credential we created earlier, and grant the proxy access to the SQL Server Integration Services (SSIS) Package subsystem.

Members of the sysadmin group have access to all proxies. The Principals page enables non-sysadmin logins or server roles to be granted access to the proxy, thereby enabling such users to create and execute SQL Agent jobs in the context of the proxy's credential.

Figure 6.6. A proxy is defined with a credential and granted access to one or more subsystems. Once created, it can be used in SQL Agent jobs to limit permissions.

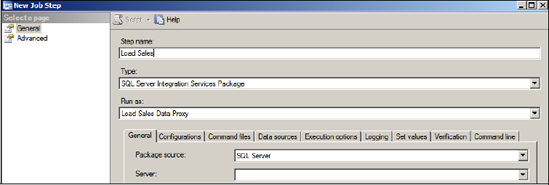

Figure 6.7. A SQL Agent job step can be run under the context of a proxy.

With the proxy created, we can now create a SQL Agent job that uses it.

SQL Agent job steps

When you create a SQL Server Agent job, one of the selections available for each job step is choosing its execution context, or Run As mode. For job steps that perform actions at the operating system level, you have two options for the Run As mode: SQL Agent Service Account or Proxy. As shown in figure 6.7, we've created a SQL Agent job with a job step called Load Sales that uses the Load Sales Data Proxy that we created earlier.

The end result of such a configuration is that the effective permissions of the Load Sales job step are those of the proxy's credential, which is restricted to the requirements of the SSIS package and nothing more, and therefore meets the least privilege objective. Additional SQL Agent jobs and their associated steps can use the Load Sales Data proxy, or have specific proxies created for their unique permission requirements, all without needing to alter the permissions of the service account used for SQL Server Agent.

It's important to note that T-SQL job steps continue to run in the context of the SQL Agent job owner. The proxy/credential process I've described is specific to job steps accessing resources outside of SQL Server.

The ability to create multiple proxies for specific job types and with individual credentials and permissions allows you to implement a powerful and flexible permissions structure—one that conforms to the principles of least privilege.

In finalizing our coverage of least privilege, let's turn our attention to how user's permissions are secured within a server and database using role-based security.

6.3.4. Role-based security

When discussing security in SQL Server, the terms principal and securable are commonly used. A principal is an entity requesting access to SQL Server objects (securables). For example, a user (principal) connects to a database and runs a select command against a table (securable).

When a principal requests access to a securable, SQL Server checks the permissions before granting or denying access. Considering a database application with hundreds or thousands of principals and securables, it's easy to understand how the management of these permissions could become time consuming. Further, the difficulty in management could lead to elevated permissions in an attempt to reduce the time required to implement least privilege.

Fortunately, SQL Server offers several methods for simplifying permissions management. As a result, you can spend more time designing and deploying granular permissions to ensure the least privilege principle is applied all the way down to individual objects within a database.

While a full analysis of permissions management is beyond the scope of this book, it's important we spend some time looking at the means by which we can simplify and tighten permissions management using role-based security. Let's start with a look at database roles.

Database roles

A database role, defined within a database, can be viewed in a similar fashion to an Active Directory group in a Windows domain: a database role contains users (Windows or SQL Server logins) and is assigned permissions to objects (schema, tables, views, stored procedures, and so forth) within a database.

Take our earlier example of the difficulty of managing the database permissions of thousands of users. Using database roles, we can define the permissions for a database role once, and grant multiple users access to the database role. As such, the user's permissions are inherited through the role, and we needn't define permissions on a user-by-user basis. Should different permissions be required for different users, we can create additional database roles with their own permissions.

Let's walk through an example of creating and assigning permissions via a database role. To begin, let's create a role called ViewSales in a database called SalesHistory using T-SQL, as shown in listing 6.1. We'll assign permissions to the role, select permissions on a view and table, and execute permissions on a stored procedure.

Example 6.1. Creating a database role

-- Create the Role USE [SalesHistory] GO CREATE ROLE [ViewSales] GO -- Assign permissions to the role GRANT EXECUTE ON [dbo].[uspViewSalesHistory] TO [ViewSales] GO GRANT SELECT ON [dbo].[Store] TO [ViewSales] GO GRANT SELECT ON [dbo].[vwSalesRep] TO [ViewSales] GO |

With the database role in place, we can now assign logins to the role and have those logins inherit the role's permission. Consider the T-SQL code in listing 6.2.

Example 6.2. Assigning logins to a database role

-- Create Logins from Windows Users USE [MASTER] GO CREATE LOGIN [WIDGETINCJSMith] FROM WINDOWS WITH DEFAULT_DATABASE=[SalesHistory] GO CREATE LOGIN [WIDGETINCKBrown] FROM WINDOWS WITH DEFAULT_DATABASE=[SalesHistory] GO CREATE LOGIN [WIDGETINCLTurner] FROM WINDOWS WITH DEFAULT_DATABASE=[SalesHistory] GO -- Create Database Users mapped to the Logins USE [SalesHistory] GO CREATE USER JSMith FOR LOGIN [WIDGETINCJSMith] GO CREATE USER KBrown FOR LOGIN [WIDGETINCKBrown] GO CREATE USER LTurner FOR LOGIN [WIDGETINCLTurner] GO -- Assign the Users Role Membership EXEC sp_addrolemember N'ViewSales', N'WIDGETINCJSmith' GO EXEC sp_addrolemember N'ViewSales', N'WIDGETINCKBrown' GO EXEC sp_addrolemember N'ViewSales', N'WIDGETINCLTurner' GO |

The code in listing 6.2 has three sections. First, we create SQL Server logins based on existing Windows user accounts in the WIDGETINC domain. Second, we create users in the SalesHistory database for each of the three logins we just created. Finally, we assign the users to the ViewSales database role created earlier. The net effect is that the three Windows accounts have access to the SalesHistory database with their permissions defined through membership of the database role.

Apart from avoiding the need to define permissions for each user, the real power of database roles comes with changing permissions. If we need to create a new table and grant a number of users access to the table, we can grant the permissions against the database role once, with all members of the role automatically receiving the permissions. In a similar manner, reducing permissions is done at a role level.

Not only do roles simplify permissions management, they also make permissions consistent for all similar users. In our example, if we have a new class of users that require specific permissions beyond those of the ViewSales role, we can create a new database role with the required permissions and add users as appropriate.

In cases where permissions are defined at an application level, application roles can be used.

Application roles

In some cases, access to database objects is provided and managed as part of an application rather than direct database permissions granted to users. In such cases, there's typically an application management function where users are defined and managed on an administration screen. In these cases, application roles can be used to simplify permissions. In effect, the application role is granted the superset of the permissions required, with the individual user permissions then managed within the application itself.

Application roles are invoked on connection to SQL Server by using the sp_setapprole stored procedure and supplying an application role name and password. As with a SQL Server login, you must ensure the password is stored in a secure location. Ideally, the password would be stored in an encrypted form, with the application decrypting it before supplying it to SQL Server.

The side benefit of application roles is that the only means through which users are able to access the database is via the application itself, meaning that direct user access using tools such as SQL Server Management Studio is prevented.

In closing this section, let's consider two additional types of roles: fixed server and database roles.

Fixed server roles

In environments with lots of server instances and many DBAs, some sites prefer to avoid having all DBAs defined as members of the sysadmin role and lean toward a more granular approach whereby some DBAs are allocated a subset of responsibilities. In supporting this, SQL Server provides a number of fixed server roles in addition to the sysadmin role, which grants the highest level of access to the server instance.

An example of a fixed server role is the processadmin role, used to grant users permissions to view and kill running server processes, and the dbcreator role, used to enable users to create, drop, alter, and restore databases. SQL Server BOL contains a complete listing of the fixed server roles and their permissions.

Similar to fixed server roles, fixed database roles come with predefined permissions that enable a subset of database permissions to be allocated to a specific user.

Fixed database roles

In addition to the db_owner role, which is the highest level of permission in a database, SQL Server provides a number of fixed database roles. Again, all of these roles and descriptions are defined in BOL. Commonly used fixed database roles are the db_datareader and db_datawriter roles, used to grant read and add/delete/modify permissions respectively to all tables within a database.

One of the nice features of permissions management within SQL Server is that roles can include other roles. For example, the db_datareader role could contain the custom ViewSales database role that we created earlier, in effect granting select permissions on all tables to members of the ViewSales role, in addition to the other permissions granted with this role.

So far in this chapter, we've addressed techniques used to prevent unauthorized access. If such access be gained, it's important we have auditing in place, a topic we'll address next.