10.5. Database snapshots

A common step in deploying changes to a database is to take a backup of the database prior to the change. The backup can then be used as a rollback point if the change/release is deemed a failure. On small and medium databases, such an approach is acceptable; however, consider a multi-terabyte database: how long would the backup and restore take either side of the change? Rolling back a simple change on such a large database would take the database out of action for a considerable period of time.

Database snapshots, not to be confused with snapshot backups,[] can be used to address this type of problem, as well as provide additional functionality for reporting purposes.

[] Snapshot backups are specialized backup solutions commonly used in SANs to create near-instant backups using split-mirror (or similar) technology.

First introduced in SQL Server 2005, and only available in the Enterprise editions of SQL Server, snapshots use a combination of Windows sparse files and a process known as copy on write to provide a point-in-time copy of a database. After the snapshot has been created, a process typically taking only a few seconds, modifications to pages in the database are delayed to allow a copy of the affected page to be posted to the snapshot. After that, the modification can proceed. Subsequent modifications to the same page proceed without delay. Initially empty, the snapshot grows with each database modification.

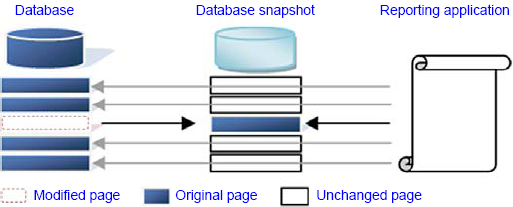

Figure 10.7. Pages are copied to a database snapshot before modification; unchanged page requests are fulfilled from the source database.

As figure 10.7 shows, when a page in a database snapshot is read, if the page hasn't been modified since the snapshot was taken, the read is redirected to the source database. Conversely, modified pages will be read from the snapshot, thus allowing consistent, point-in-time results to be returned.

Let's take a look now at the process of creating a snapshot.

10.5.1. Creating and restoring snapshots

A database snapshot can be created using T-SQL, as shown here:

-- Create a snapshot of the AdventureWorks database

CREATE DATABASE AdventureWorks2008_Snapshot_20080624 ON (

NAME = AdventureWorks2008_Data

, FILENAME = 'E:SQL DataAdventureWorks_Data.ss'

)

AS SNAPSHOT OF [AdventureWorks2008];

GOAs you can see in figure 10.8, a snapshot is visible after creation in SQL Server Management Studio under the Database Snapshots folder. You can select it for querying as you would any other database.

Given its read-only nature, a snapshot has no transaction log file, and when created, each of the data files in the source database must be specified in the snapshot creation statement along with a corresponding filename and directory. The only exceptions are files used for FileStream data, which aren't supported in snapshots.

Figure 10.8. A database snapshot is visible in SQL Server Management Studio under the Database Snapshots folder.

You can create multiple snapshots of the same database. The only limitations are the performance overhead and the potential for the snapshots to fill the available disk space. The disk space used by a snapshot is directly determined by the amount of change in the source database. After the snapshot is first created, its footprint, or used space, is effectively zero, owing to the sparse file technology. With each change, the snapshot grows. It follows that if half of the database is modified since the snapshot was created, the snapshot would be roughly half the size of the database it was created from.

Once created, a database can be reverted to its snapshot through the RESTORE DATABASE T-SQL command using the FROM DATABASE_SNAPSHOT clause as shown here (this example will fail if the AdventureWorks database contains FileStream data). During the restore process, both the source and snapshot databases are unavailable and marked In Restore.

-- Restore the AdventureWorks database from the snapshot USE master GO RESTORE DATABASE AdventureWorks2008 FROM DATABASE_SNAPSHOT = 'AdventureWorks2008_Snapshot_20080624'; GO

There are a number of restrictions with reverting to snapshots, all of which are covered in Books Online. The major ones are as follows:

A database can't revert to a snapshot if more than one snapshot exists. In such a case, all snapshots should be removed except the one to revert to.

Despite the obvious advantages of snapshots, they're no substitute for a good backup strategy. Unlike a database restore with point-in-time roll-forward capabilities, a database reverted to a snapshot loses all data modifications made after the snapshot was taken.

Restoring a snapshot breaks the transaction log backup chain; therefore, after the restore, a full backup of the database should be taken.

Databases with FileStream data can't be reverted.

Given the copy-on-write nature of snapshots, there's a performance overhead in using them, and their unique nature means update and delete modifications aren't permitted against them—that is, they're effectively read-only databases for the duration of their existence. To reduce the performance overhead, older snapshots that are no longer required should be dropped using a DROP DATABASE command such as this one:

-- Drop the snapshot DROP DATABASE AdventureWorks2008_Snapshot_20080624

To fully understand the power of database snapshots, let's cover some of the many different ways they can be used.

10.5.2. Snapshot usage scenarios

Database snapshots are useful in a variety of situations. Let's cover the most common uses, beginning with reporting.

Reporting

Given a snapshot is a read-only view of a database at a given moment, it's ideal for reporting solutions that require data accurate as at a particular moment, such as at the end of a financial period.

The major consideration for using snapshots in this manner is the potential performance impact on the source database. In addition to the copy-on-write impact, the read impact needs to be taken into account: in the absence of a snapshot, would you run reports against the source database? If the requested data for reporting hasn't changed since the snapshot was taken, data requested from the snapshot will be read from the source database.

A common snapshot scenario for reporting solutions is to take scheduled snapshots, for example, once a day. Given each snapshot is exposed as a new database with its own name, reporting applications should ideally be configured so that they are aware of the name change and be capable of dynamically reconnecting to the new snapshot. To assist in this process, name new snapshots consistently to enable a programmatic reconnection solution. Alternatively, synonyms (not covered in this book) can be created and updated to point to the appropriate snapshot objects.

Reading a database mirror

We'll cover database mirroring in the next chapter, but one of the restrictions with the mirror copy of a database is that it can't be read.

When you take a snapshot of the database mirror, you can use it for reporting purposes, but the performance impact of a snapshot may lead to an unacceptable transaction response time in a synchronous mirroring solution, a topic we'll cover in the next chapter.

Rolling back database changes

A common use for snapshots is protecting against database changes that don't go according to plan, such as a schema change as part of an application deployment that causes unexpected errors. Taking a snapshot before the change allows a quick rollback without requiring a full database backup and restore.

The major issue with rolling back to a snapshot in this manner is that all data entered after the snapshot was created is lost. If there's a delay after the change and the decision to roll back, there may be an unacceptable level of data changes that can't be lost.

For changes made during database downtime, when change can be verified while users aren't connected to the database, snapshots can provide an excellent means of reducing the time to deploy the change while also providing a safe rollback point.

Testing

Consider a database used in a testing environment where a given set of tests needs to be performed multiple times against the same data set. Traditionally, a database backup is restored between each test to provide a repeatable baseline. If the database is very large, the restore delay may be unacceptably long. Snapshots provide an excellent solution to this type of problem.

DBCC source

Finally, as you'll see in chapter 12, a DBCC check can be performed against a database snapshot, providing more control over disk space usage during the check.

In closing the chapter, let's focus on a very welcome addition to SQL Server 2008: backup compression.