Understanding Business Continuity Plans

Business continuity planning includes all the processes and procedures to prevent mission-critical services from being interrupted or disrupted. A business continuity plan (BCP) also includes disaster recovery elements used to restore the organization to fully functioning operations as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Several events can result in service disruptions, including any of the following:

• Attacks

• Disasters

• Accidents

• Human error

• Equipment failure

• Software or application failure

It’s worth stressing that business continuity planning isn’t a small endeavor. When organizations take it seriously, it entails quite a bit. Figure 12-3 shows the overall steps to develop a BCP.

Figure 12-3 Overall steps for a BCP

The business impact analysis (discussed in more depth in the next section) identifies critical functions within the organization and provides an important starting point. The organization uses these results to develop recovery strategies, such as the use of alternate sites and different backup strategies. Once the strategies are identified, individual plans are created to support the strategies. These plans include detailed steps that can be used in response to a disaster or emergency. The steps must be tested to ensure that they work as expected. Last, personnel are trained to implement the plans, and the plans are regularly reviewed to ensure that they still meet the needs of the organization.

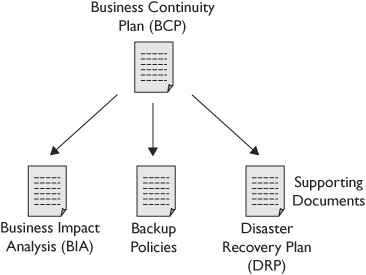

Figure 12-4 illustrates the relationship between a BCP and supporting policies. For example, a BCP starts with a business impact analysis (BIA) to determine what functions are critical, and also includes backup policies to identify critical data to back up, as well as recovery strategies that are documented in a disaster recovery plan (DRP).

Figure 12-4 BCP and supporting elements

TIP The BCP is the primary document used for business continuity. It includes a BIA and other supporting documents based on the needs of the organization.

Some organizations are in high-risk zones for specific types of events, so they often create supporting documents specifically for these events. For example, an organization that is in a high-risk zone for hurricanes would have a document specifically targeted at ensuring that critical operations continue during a hurricane.

Before the hurricane season begins, the organization dusts off last year’s hurricane preparation plan and reviews it. It may decide that it wants to continue to operate critical functions for ten days to ensure that they have ten days of diesel fuel for generators and ten days of food and water stored for personnel who will remain onsite. This plan would also identify exactly what the organization does as a hurricane is approaching, such as when it is within 72 hours, 48 hours, 24 hours, and 12 hours of striking.

For example, when the hurricane is within 72 hours, supplies are checked and items that are outside of the organization’s facility are brought inside. When the hurricane is within 48 hours of the facility, the organization tests the generators and ensures that everything can continue to operate if the storm hits. When the hurricane is within 24 hours, emergency personnel report to work and all other personnel are sent home.

TIP The actual steps that the organization takes are identified in the hurricane preparation document and may be different from the steps identified in this timeline. However, the point is that the members don’t have to guess about what they should do, but instead simply follow the checklists in the BCP. Even if this is the first time that some of the personnel are experiencing a hurricane, they have the benefit of experience that is documented in these checklists.

Business Impact Analysis

A BIA is an important part of a BCP. It identifies the impact to the organization if any business functions are lost due to any type of incident. This information helps an organization identify what business functions are critical to continued operations by identifying the impact to the business if a business function stops.

For example, if a weather event caused a power outage in a building, will this stop the business from functioning? The answer depends on what functions are performed in the building and whether any of these functions are critical. If this building housed primary servers used in an online e-commerce site, the loss of power could cause the entire business to cease functioning. In this case, the purchase of generators for long-term alternative power may be justified. However, if the building was used to ship purchased products, a 24-hour or 48-hour power outage may have only a minor impact on operations.

The BIA evaluates both direct costs and indirect costs. Direct costs are associated with the immediate loss, such as an immediate loss to sales, while indirect costs are expenses related to recovering from the loss. For example, if an e-commerce web server normally generated $5,000 in revenue an hour, than the direct costs are $5,000 for every hour the server is down. However, the organization may have to spend money on public relations to assure customers, and this extra money represents indirect costs. Additionally, some customers may leave forever, causing additional indirect costs.

Maximum Acceptable Outage and Recovery Time Objective

One of the most important findings of the BIA is the maximum acceptable outage (MAO) for different services or systems. This is the maximum amount of time that a system can be down before critical business functions are affected. For example, an online web server generating $5,000 an hour may have an MAO of 10 minutes, while a shipping system may have an MAO of 48 hours. The actual MAO is highly flexible from one organization to another. Organizations make a determination for themselves based on their business model.

NOTE MAO is sometimes called maximum tolerable outage (MTO) or maximum tolerable period of disruption (MTPOD). However, each of these terms means the same thing.

The MAO helps an organization determine the recovery time objective (RTO). The RTO is the maximum amount of time that can be taken to restore a system or process to operation. If a failure takes longer than the RTO to restore, then the mission is impacted. The RTO drives the recovery methods used.

Recovery Point Objective

A recovery term often associated with databases is recovery point objective (RPO). An organization needs to ask itself what data is acceptable to lose if a database fails? If an organization has a relatively static database with just a few manual updates during the week, then the organization may determine that the RPO is a single week. In other words, the organization can back up the database weekly; then if it is lost, the organization can restore the database from the backup and then update the database with the manual updates since the backup.

However, if a database is recording online transactions, a failure on Wednesday would result in a loss of all transactions since Saturday night if only weekly backups were done. If the database has thousands of updates during this time, this loss may be unacceptable. In this case, the RPO may be up to the moment of failure.

TIP Database backup strategies can include full and differential backups and the backup of database transaction logs. The transaction logs record every database transaction since the last backup (full or differential) and can be used to restore the database up to the moment of failure.

Although it’s certainly achievable to create a backup strategy for databases to recover a failed database up to the moment of failure, such a strategy is quite expensive. It’s important to determine the actual needs of the organization to determine the RPO. If the BIA determines the organization has a need to restore the database up to the moment of failure, the extra expense to support this RPO is justified.

NOTE Although an RPO is most often associated with databases, the same concepts can be applied to any type of backup.

One of the major outputs of the BIA is a document that identifies the actual monetary losses that can result from the outage of a critical business function. This is invaluable when you are evaluating controls that can mitigate these losses. You may remember from Chapter 9 that the controls are valuable only if they cost less than the losses they’re trying to protect. For example, you wouldn’t spend $1,000 to protect a $10 keyboard. Similarly, you don’t want to spend business continuity funds protecting business functions that aren’t critical. Although an e-commerce web server may be critical to an organization, an intranet web server used to track long-term projects may not be critical.

The BIA identifies how much money can be lost if the e-commerce web server fails and provides management with an idea of the justified costs to keep the system operational even during a major incident.

Figure 12-5 shows one way that a BIA attempts to analyze the probability of an incident and the incident’s impact if it occurs. By graphing different types of disasters and identifying the systems that they can affect, an organization can identify the incidents that deserve the greatest attention.

Figure 12-5 Probability and impact analysis

Historical data helps an organization predict the probability of specific disasters, and the loss of specific services and functions are evaluated to determine the impact. For example, an organization in San Francisco may consider the threat of an earthquake to be significant, while the threat of a hurricane may be nonexistent. Similarly, an organization in Miami may consider the threat of a hurricane to be significant, while the threat of an earthquake may be nonexistent. Although these are extreme examples, other examples aren’t so easy to determine. However, by analyzing and charting the results, the organization can prioritize different risks.

Disaster Recovery Plan

A DRP provides an organization with a plan to restore critical operations after a disaster. The overall goal is to provide employees who are recovering systems with clear-cut steps on what to do and the order of these steps.

Disasters are major events, and people don’t always think clearly when they occur. If employees have steps to follow within a checklist, they can ensure that systems are restored in an orderly manner. On the other hand, if employees don’t have steps to follow, they may spend a lot of time trying to determine what to do, and then more time redoing their steps when things don’t work as planned.

EXAM TIP Disaster recovery and fault tolerance are not the same thing. Disaster recovery helps an organization recover after a disaster. Fault tolerance helps ensure that a system or component continues to function after a failure. Chapter 9 covered fault-tolerance strategies such as RAID and failover clusters.

Comparing a BCP and a DRP

It’s important to recognize the differences between a BCP and a DRP. Although many people and even some organizations combine them into one document, they are different documents used for different purposes. In short, the BCP has a much wider scope and helps an organization continue to operate. In contrast, the DRP is a part of the BCP and is used only to restore a system to operation after an incident results in a major failure.

For example, if an organization is in the midst of a disaster and needs to move operations to an alternate location, the BCP would provide the details on where the alternate location is and what business functions it will perform. After the disaster, the DRP would provide the details on how to restore operations at the primary location.

EXAM TIP The BCP provides the information to keep critical functions running during a disaster (such as which critical functions to move to an alternate location). A DRP has a narrower focus and identifies how one or more individual systems can be recovered after a failure.

Even though a BCP and a DRP are not the same thing, you may run across documentation that treats them as though they are the same. However, (ISC)2 documentation distinguishes between the two.

Alternate Locations

If an organization determines that it must be able to continue operations even if only a single location suffers a catastrophic failure, it must designate an alternate location. For example, banks and investment companies need to provide access to customer data even if a weather event (such as a tornado, flood, or hurricane) causes so much damage to one location that they can no longer operate at that location.

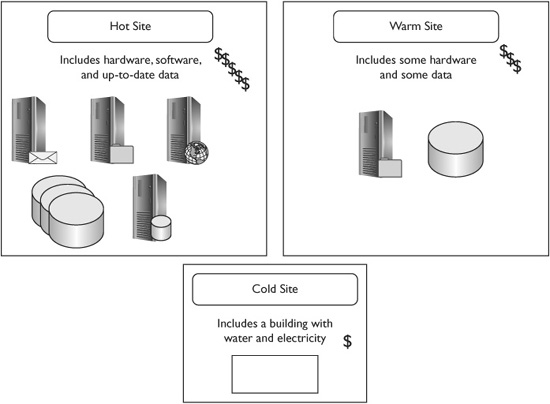

Depending on the needs of the organization, it can choose a hot site, a cold site, or a warm site. These different types of sites provide different services and have different costs. Figure 12-6 provides an overall view of each of these types of alternate locations and they are explained in more depth in the following subsections.

Figure 12-6 Comparison of alternate locations

Hot Site

A hot site includes all of the resources necessary to take over the operations of another location in a very short period of time, sometimes within minutes. This includes hardware such as servers and the network infrastructure, up-to-date data, and personnel to manage the functions of the alternate location.

Hot sites are valuable if an organization needs to prepare for a catastrophic failure that can occur at any time. For example, many banks and investment companies have hot sites in case of major incidents, such as the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Organizations that operate in earthquake or tornado zones often need to have hot sites available. Hot sites are the most expensive of the three alternate location types. However, hot sites are the easiest to test, because everything is in place.

It’s rare for a hot site to be used only as an alternate location for an organization. Instead, it is used for less critical operations the majority of the time, but it is kept in a ready state to take over the critical operations at a moment’s notice. For example, the organization could have a location that provides basic customer services, but also hosts the equipment and infrastructure as a hot site. The majority of the time, the location only provides customer services. However, in the event of an emergency, the customer services could be scaled back to dedicate resources to take over for the primary location.

Similarly, regional locations often have the capability of taking over another region’s services. For example, an organization can have major locations in the western and eastern parts of a country. If either region’s location fails, the other location can take over the critical operations of the failed location.

Cold Site

A cold site is a building with a roof, running water, and electricity. It doesn’t include the necessary hardware, software, or personnel. In the event of an emergency, all of the resources must be moved to the cold site location, hooked up, and configured for operation.

It’s difficult to test a cold site, because nothing exists at the location. However, a cold site is significantly cheaper to maintain.

Warm Site

A warm site is a compromise between a cold site and a hot site. The organization makes compromises with costs and time. Instead of ensuring that the site can be brought up in moments, the organization may decide that 24 hours’ notice is enough to bring it online.

For example, an organization may operate in a hurricane zone. Because hurricanes travel relatively slowly, communities often have more than a days’ notice of a possible hurricane landfall. When a storm is approaching, the organization can use the time to implement a plan to bring the warm site up and operational, update all of the data, and deploy a team to man the site during the emergency.