CHAPTER ONE

KNOW YOUR TERRITORY: THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF GUERRILLA GRANTSMANSHIP

A guerrilla unit should be thoroughly familiar with the terrain of its region of action.

MAO TSE-TUNG, BASIC TACTICS

Before you embark on a journey into unfamiliar territory, it's always a good idea to study a map. Likewise, before you begin seeking grants you need to become familiar with the “lay of the land” and the basic modes of getting around in this area.

This chapter introduces the essential elements of guerrilla grantsmanship. We will address three key questions:

- How can I best relate to grantmakers?

- Who's calling the shots?

- How can I get to the grantmaker?

Equipped with this orientation, you will find it easier to implement the strategies described in later chapters.

Understanding the Funding Relationship

As a grantseeker, your greatest challenge is to develop a good relationship with your grantmaker. Calling this the funding relationship highlights the purpose of the alliance from your perspective.

On the surface, what you want from a funding relationship appears quite simple: financial support in the form of grants. But the tendency to concentrate on one's own needs is exactly the reason so few grantseekers are successful. In funding relationships, as in virtually all relationships, an altruistic strategy seems to work best. The more you concentrate on your partner's needs, the more likely it is that your own needs will be met.

Individual grantmakers have different needs at different times, but some needs and expectations are universal and constant, arising as they do from the basic dynamic of the funding relationship. If you understand this dynamic and conduct yourself in such a way that you meet the grantmaker's expectations, you stand a much better chance of getting what you want from the relationship. What is this basic dynamic? Simply that grantmakers are prospective customers, and they expect to be treated as such.

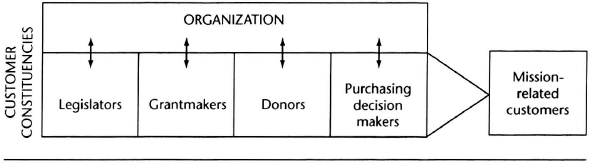

Five Customer Constituencies of Nonprofit Organizations

If you are like many nonprofit executives, you may not be accustomed to viewing grantmakers as your customers, but it is helpful to do so as you begin thinking about the relationship into which you are entering. Actually, in the course of your career you have probably been involved in meeting the needs of several customer constituencies; see Figure 1.1.

To help you develop the strategies you will use to meet the needs of grantmakers, let's look briefly at each of these constituencies: who they are, how they relate to the organization, and their primary needs as customers.

Mission-Related Customers

Mission-related customers are those who use the services of the organization, such as the students of a school, clients of a social service agency, audience of a performing arts organization, or patients of a hospital. They are your most important customer constituency, for without them your organization has no reason to exist.

As organizations and their mission-related customers vary widely, the needs of a specific group of customers will also vary. However, all of them want excellence in service and responsiveness to their needs.

The relationship between mission-related customers and the organization's staff is direct, concrete, and often intimate. For instance, the very lives of patients in a hospital are in the hands of hospital staff, and the future careers of students in a school may be strongly influenced by the teachers they encounter.

FIGURE 1.1. THE NONPROFIT'S CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS.

Although mission-related customers are essential to the nonprofit organization, they can never be its only constituency because they alone cannot keep it financially viable. Many nonprofits provide their services either for free, as in the case of a hunger center, or on a sliding scale, as in the case of a counseling service. Even if all clients pay the highest rate, the fees generated rarely cover the total costs, so the difference must be made up by others.

Purchasing Decision Makers

For some organizations, an important customer constituency is made up of purchasing decision makers, such as the parents who select schools and pay tuition for their children or the third-party payers who select health care providers and pay medical bills for patients.

The relationship between purchasing decision makers and the organization is less immediate and less concrete than in the case of mission-related customers. This relationship hinges on selection criteria and the values that drive the decision-making process. For insurers who select health care providers, for example, low cost is usually the highest priority; for parents of college-age children, the nature and quality of educational programming are the highest priorities, along with cost.

Once the selection is made, purchasing decision makers need the organization to deliver as promised so that they receive as few complaints as possible from the mission-related customers they represent. Purchasing decision makers can make it either easy or impossible for mission-related customers to use the service, and will do so based on whether the organization meets users' needs. Today's health care environment provides an extreme example: when nonprofit hospitals are unable to satisfy the needs of third-party payers, they may be acquired by for-profit chains or may even close their doors.

Donors

Another group of customers is made up of donors—those who make philanthropic gifts to the organization. These gifts may be used to reduce the gap between operating expenses and income, to implement new programs and services, to expand existing programs and services, to construct new physical facilities, or to expand, renovate, or equip existing facilities.

The relationship between donor and organization may be limited to the writing of a check, in which case it will be more abstract than the relationships with mission-related customers or purchasing decision makers. Many donors, however, are also current or former members of other constituencies. Some may be members of the governing board or other volunteer groups. In these cases, the relationship is clearly complex.

The needs of donors are as varied as the motivations that prompt them to give. The organization may meet a donor's need for recognition, for networking, or for social acceptance; other donors need confirmation that they are “doing the right thing” in terms of their personal philosophy or the values imparted by their families. On the highest level, an organization can help donors attain personal fulfillment or self-actualization through their acts of philanthropy, which do indeed provide enduring benefits to the community or society.1

For this discussion, individual donors are considered separately from grantmakers, who conduct their philanthropic activities through a foundation, corporation, or government agency. In the case of foundations established and controlled by individuals or families, however, the distinction may be a fine one, as we will see.

Legislators

The fourth group of customers is made up of legislators—elected officials who make the laws that dictate the form and amount of public support for nonprofit organizations. The relationship between legislators and specific nonprofits is more distant and abstract than any of the others we have discussed. Legislation deals with social outcomes, and nonprofits merely serve as an instrument to accomplish these outcomes.

For instance, the legislation that established Medicaid provides that medical care must be made available to poor people. When a hospital provides services reimbursed by Medicaid, it becomes, in effect, a government contractor that offers something promised by legislation and is compensated for it according to the terms of the law. The relationship between legislators and nonprofits, then, is defined by the legislation that authorizes the service and the appropriation to pay for it. What legislators want from this relationship is the assurance that the services provided are indeed those desired by their constituents, and that the constituents are satisfied with the services they receive.

Grantmakers: Your Fifth Customer Constituency

Now that we have examined four customer constituencies in a new light, you may be prepared to consider grantmakers as a fifth, whose needs require the same attention, resourcefulness, and intelligence you customarily employ to satisfy the needs of your other constituents.

In the grantseeking process, you will encounter several different types of grantmaking organizations. These may be staffed or unstaffed (that is, managed by paid professionals or simply by trustees); they may award grants on a local, state, regional, or national basis; and their assets may range from a few thousand dollars into the billions. Their interests are as varied as the realm of philanthropy itself—from animal welfare and civic beautification to medical research, education, and cultural advancement.

There are currently over 625,000 charities registered with the federal government, and the number is growing rapidly. For instance, in 1994, there were 599,745 registered charities, and by 1995, this number had risen to 626,226.2 But according to the Foundation Center, there exist fewer than 11,000 foundations that give away $50,000 or more per year. As recently as 1992, foundations employed only slightly more than 6,000 professional staff, of whom about 30 percent worked for twelve of the largest national foundations.3

There are several kinds of foundations. Individual or family foundations are funded by contributions from individual benefactors or families who often exercise a high degree of influence, directly or indirectly, on the awarding of grants. Many of these foundations are established through a substantial bequest upon the death of the founder, which may later be augmented by contributions from other family members. The family foundation executive, if there is one, may be an attorney or other trusted family advisor who does the job part-time. At the other extreme, some family foundations built upon great private fortunes have grown into the world's most powerful grantmaking organizations, sometimes employing more professional staff than many of the nonprofits with whom they deal.

Corporate foundations are funded by major corporations, normally with annual contributions that vary with the company's profits. The foundation executive is usually a company employee who may have other responsibilities in public relations or community relations.

Community foundations are funded by contributions from numerous individuals and families in a given community, and limit their grantmaking activities to that community. Although grant awards are ultimately approved by the foundation board or its distribution committee, many donors retain a degree of discretion over awards made from the funds they contribute. Larger community foundations—such as The Cleveland Foundation, the first to be established—may employ several professional staff, including specialists in various areas.

Government agencies whose primary purpose is to make grants are funded by public contributions, generally through annual legislative appropriations. Prominent examples include the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, which operate specific programs through state councils of the arts and humanities. Most of these organizations are professionally managed and are advised by appointed boards of directors. In addition, government agencies at all levels—local, regional, state, and national—also operate ad hoc grantmaking programs mandated by current legislation. In working with these agencies, you may deal with an appointed board or an agency official; such agencies are valid prospects for a grantseeking effort.

Just as nonprofits do with their endowments, most individual, family, and community foundations invest the contributions they receive from donors in an attempt to maintain the integrity of donated funds. In other words, they invest the principal and use only the interest or earnings as the primary source of grant dollars. Whether the earnings are high or low, however, foundations are required by law to give away a specific small percentage of the endowment corpus each year.

To develop a sound funding relationship with grantmakers, three things are essential: first, acknowledge that they are prospective customers and behave with proper deference; second, have realistic expectations; and third, address the grantmaker's priorities and concerns.

Showing Deference to Grantmakers

Adopting the appropriate attitude of deference to grantmakers plays out in several ways. In scheduling meetings, for instance, both the place and time should be set at the convenience of the grantmaker; as the grantseeker, you should be the one to travel or shift other commitments to accommodate the grantmaker's schedule.

The topics of your conversation should also be determined largely by the grantmaker. You may choose to develop an agenda in advance of a meeting in order to ensure that your time together is used as efficiently as possible. But if the grantmaker wishes to discuss something else, that issue should become the focus of your attention.

The timing of a grant award is also up to the grantmaker. As a grantseeker, you would usually prefer to secure funding immediately, but most private foundations and government programs stipulate a specific deadline for the submission of proposals, a specific period during which proposals can be considered, and a specific date on which awards are announced.

If you approach a grantmaker who operates an ongoing program, there may be periodic submission deadlines, perhaps quarterly or annually. Consult your grantmaker about the best time to submit your application and follow the advice you receive. If the grantmaker is not willing or able to provide support until some future funding period, you will either need to delay your project's beginning or arrange for other funding sources in the meantime.

Most important, as in relationships with all customers, you should indicate your willingness—nay, eagerness—to anticipate what the grantmaker will want or need and provide it before you are even asked. If you are unable to anticipate her wants and needs, you should at least respond as promptly as possible once asked. When you study prospective customers and try to satisfy their wants and needs, it makes it possible for them to develop the trust and confidence in you that ultimately justifies their investments in your organization's work.

Operating with Realistic Expectations

In developing a sound funding relationship (or, once again, a sound relationship of any kind), it's important to operate on the basis of realistic expectations. In the past, you may have shied away from grantseeking because you heard about others' bad experiences. But rest assured that you can avoid most problems if you simply refrain from wishful thinking.

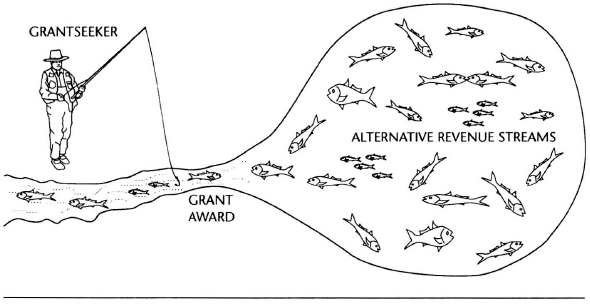

Everyone harbors an intense longing to be cared for and a deep desire for permanence. As a mature person, however, you probably accept that “living happily ever after” is the normal conclusion to events only in fairy tales and TV movies. You need to apply the same kind of realism to your grantseeking efforts. Confidence and high hopes must be tempered by the knowledge that all funding is interim funding—that the maximum duration of support from any source is a while, not forever. Thus grantseekers should always plan for life after the current grant terminates. Many grantseekers get into trouble because, deep down, they see the awarding of the grant as an end to their worries rather than as a milestone on a long road. Grantmakers, however, are generally clear and consistent in their communication: they insist that a grantseeker present a plan for supporting the project after the current funding runs out.

Problems arise when the grantseeker submits a plan for continued funding that is formulated specifically to sound reasonable to the grantmaker but that the organization cannot or does not wish to implement. If you are awarded a grant and do not pursue the plan for alternative funding, then you, your grantmaker, and everyone else involved will end up disappointed.

If you want to avoid this kind of heartache, look at the awarding of a grant as the initial step in the process, rather than the final step. Think of the period during which you will receive grant support not as a honeymoon, but as an opportunity to develop alternative sources of support. Focus on identifying and developing new revenue streams to support the activity during the next phase, if not on a continuing basis (see Figure 1.2).

Just as all funding is interim funding, all funding is partial funding. Dependency may work in some personal relationships, but it is counterproductive in a funding relationship. You may long to secure all the money you need for a project from a single funder, but grantmakers are generally put off by such a prospect.

Some foundations like to be part of a co-funding team, in which two or more grantmakers provide support, reinforce each other's judgment, and share the risk that the project may not work out. In other cases, an individual grantmaker may want to be the only private foundation to support a given project. No grantmaker, however, will likely want to be the sole source of support; each seeks assurance that you are building a diverse funding base, usually with a mix of sources of support. The most popular combination of support sources these days is the public-private partnership; another sound combination is foundation and individual support. In any case, when you meet with grantmakers, be prepared to reassure them by naming other prospective funding sources.

FIGURE 1.2. GRANT AWARDS LEAD TO ALTERNATIVE REVENUE.

Addressing the Grantmaker's Priorities

As the vendor or supplier in a buyer's market, you want to emphasize your commitment to customer service in every way possible. As in other business relationships, you as grantseeker are well advised to frame your thinking and your presentation not from your perspective, but from that of your prospective partner, the grantmaker. Accordingly, you should do some research to determine what the grantmaker is looking for.

We will cover how to conduct this research in Chapter Two. But in general, though the agenda of each is unique, virtually all grantmakers are interested in advancing the mission of the grantmaking organization and in solving a specific problem (or addressing a specific opportunity) identified as a priority by the grantmaking organization. If you can demonstrate that your project will advance the funder's mission, or solve a problem identified by the funder, then your chances of success will increase geometrically.

But the most critical issues in a funding relationship are credibility and trust. Your grantmaker must know that you are who you say you are, and that you will do what you say you will. We will discuss ways of building credibility and trust later in the book, but first we must look more closely at the grantmakers themselves to understand where their authority is vested and how to gain access to them.

Who's Calling the Shots?

Salespeople evaluate customer potential by the size of the possible sale and the effort that will be required to make it. Grantseekers evaluate grantmaker potential by the size of the possible grant and the effort that will be required to get it. This will be explored in greater depth in the next chapter; for now let's examine the issue of authority, which influences both the size of the potential grant and the ease of persuasion. By and large, grantmakers hold one of two levels of authority, direct or indirect.

Direct authority is held by the person or persons who earned or inherited the money used to create a foundation. Grantmakers with direct authority enjoy the highest level of discretion over the distribution of funds and can make decisions about grants as quickly as they wish—even invading principal or giving away the entire corpus and dissolving the foundation to give an especially large grant if they are so motivated! Clearly, from the grantseeker's point of view the simplest and most expeditious option is to deal with a grantmaker who holds direct authority.

The grantmaker with indirect authority, on the other hand, merely represents or holds a proxy for those who have direct authority. In private philanthropy, the most common forms of proxy are family relationships and professional relationships. In the family relationship, a wealthy person designates a spouse, child, or another relative or relatives to be responsible for distributing grants. In the professional relationship, a wealthy person designates a trusted advisor such as an attorney, trust officer, or financial manager to distribute grants according to the wealthy person's wishes or the professional's best judgment.

In a professional relationship, grantmaking proxy authority is usually part of the terms of employment. This is typically the case in large private foundations and always the case in public agencies that make grants. In private foundations, the proxy represents the responsibility for making grants according to the guidelines established by those with higher authority; in public agencies, the proxy represents the public trust and carries with it responsibility for making grants that implement legislative intent. How much discretion or authority is held by the professional whose authority derives from a proxy? It varies widely, depending on how much confidence the people with direct authority have in the professional who holds the proxy.

The members of a grantmaking staff are usually hired as program officers, meaning they have authority over specific grantmaking programs. At most foundations, each program officer is responsible for a portfolio of requests. Some foundations give program officers responsibility for distributing specific funds.

Although it is preferable to solicit grantmakers with direct authority, that may be difficult or impossible. Such individuals tend to keep themselves remote from grantseekers socially, geographically, or both. Therefore, if you are like most of us, you must work with grantmakers whose authority derives from a proxy. As you forge alliances with them, it helps to remember the dynamics of the proxy situation, even though on a day-to-day operating basis most proxies are largely invisible. The distance between the donor and the individual holding the proxy may be considerable, but program officers usually have such a strong sense of responsibility for and control over their portfolios that they identify with the source of the funds they are distributing. They may even make statements like, “I'm not going to put any of my money into this.” Such statements may strike you as arrogant or at least inaccurate, especially when the speaker is a government agent distributing taxpayer dollars or a community foundation officer distributing money donated by others.

But though such program officers didn't earn or inherit the money themselves, they do in fact represent those who did, and they are often largely responsible for deciding who will receive funding. For all intents and purposes, they are the customers and must be treated accordingly. The foundation's trustees, of course, have the final say on grant awards, but in most cases they merely ratify the recommendations of the professional staff In a later chapter, we will discuss the delicate matter of marshaling any influence you may have with the trustees of grantmaking organizations.

In some cases, the authority of the proxy may be quite explicit. For example, the program officer may view your project as inconsistent with the values dictated by the absolute authority. At such times, you may hear something like this: “Although I personally see this project as having merit, I know that my board would not be interested.” Because your request is being declined, such a statement may bring you little comfort. You can, however, use the program officer's declared personal interest as the basis for asking for help in identifying other prospective sources where your chances might be better.

How Can I Get to the Grantmaker?

How accessible is your grantmaker? It depends on the type of grantmaking organization and the individual's level of authority.

Program officers at most community foundations and government agencies are fairly accessible to most legitimate grantseekers. Busy program people may use screening or delaying tactics, such as requiring something in writing about a project before they agree to a meeting. Nonetheless, they will eventually agree to meet so long as the grantseeker can establish legitimacy by demonstrating that the organization she represents is eligible for a grant and that she has a specific project in mind that is appropriate for grant support.

In general, the higher the level of authority, the less available a person is. It can be fairly difficult for the average grantseeker to reach heads of federal agencies or trustees of national foundations. When the stakes are high and the competition is stiff, however, it may be worthwhile to spend some time and energy developing access to such individuals. This is a little-understood but critically important element of the grantseeking process. Methods of developing access depend on the sources of access—direct, indirect, or paid—you choose to utilize.

Direct Access

All access develops from situations where people come together and become acquainted. You probably have or could get access to more people than you think. A review of your potential sources of access may demonstrate that your network is large enough to do you some good.

As you think about the people to whom you have direct access, you can begin to identify those in a position to help you in the process. In general, the closer the relationship, the more good it can do you. There are times when the access provided by good friends is in itself sufficient to generate grant support. If the right person does the asking, the specific cause matters little as long as it falls somewhere within the grantmaker's purview.

Most of us have several potential sources of access to people: family, school, military service, and social, professional, and community activities. The circumstances of your birth provide you with access to an immediate family, and beyond this core group is an extended family brought about by births, marriages, divorces, and remarriages. So you frequently gain access to new people as they become relatives, or as children grow up and develop their own family networks.

From nursery school through graduate school, you had classmates—people with whom you shared significant experiences. If you went to boarding school, you may have gotten to know your classmates even better. In any event, if you made a phone call today to the person who sat next to you in tenth-grade geometry, you would probably get a fairly prompt response. Also during your school years, you probably were introduced to people through extracurricular activities. Sports teams, musical ensembles, school newspapers—all of these put you in contact with people who came to know you, likely remember you, and will at least listen to a request for help.

If you were in the military, people with whom you served usually remain accessible, having shared intimate and even life-changing experiences. If you served when the draft was still in effect, you may have met people who are now in a position to do you some good in civilian life.

Once you are out of school and the service, you meet people through social, professional, and community activities. As a working person, you probably meet and get to know people at all levels of your organization; through professional or business groups, you meet people working for other employers who have backgrounds, skills, and responsibilities similar to your own. As a community resident, you meet a wide variety of people, getting to know your neighbors just because they live nearby and making acquaintances at religious services, concerts, lectures, sporting events, and the like with people who share your interests and values. You get to know others because they share your life situations—other parents, other members of the same profession, even other people with the same disease or addiction.

No matter how reclusive a life you may think you lead, you probably come to the grantseeking table with a sizable network of people to whom you have direct access. In the next chapter we will explore how you go about identifying all the people you know who are involved in the grantmaking process. Meanwhile, you may still be concerned that among the circle of people to whom you have direct access, very few are in a position to assist you in your grantseeking efforts. This may indeed be the case. As a resourceful grantseeker, however, your access is not limited to people you know directly.

Indirect Access

You have indirect access to people who are known by people you know—friends of a friend, that is. Thus for everyone to whom you do have direct access, you have indirect access to several others. To determine in advance how much good an indirect introduction can do, you need to look at several factors:

- How close is your relationship with the person you want to act as your intermediary?

- How close is the relationship between your intermediary and the person (grantmaker) you want to meet?

- Does the grantmaker hold your intermediary in high regard? Will this association help to enhance your image? Will it help to establish you as a credible, trustworthy person?

- Does your intermediary have any influence with the grantmaker?

The answers to these questions will help you forecast how effective the introduction will be in positioning you with the grantmaker.

Paid Access

As in almost any other held of human endeavor, if you cannot identify a source of direct or indirect access to a grantmaker, you can pay for it. The kind of paid help you seek will depend on the funding source you want to approach. As we review each group of prospective funders—foundations, corporations, and government agencies—we will identify sources of paid access. For now, suffice it to say that regardless of financial concerns, it is generally better to use voluntary access than to pay for it. Volunteers simply have more credibility and influence than “hired guns.” However, if the choice is paid access or no access, hiring someone might prove a wise investment. In grantseeking, as in any business enterprise, it takes money to make money.

Obviously, the person who is paid to introduce you has to be known to the grantmaker. In addition to providing an introduction, your intermediary should lay the groundwork for establishing a good relationship between you and your prospective customer. You can have the intermediary present your credentials, the true basis for your credibility. These include your education, professional experience, track record, and any kind of public recognition you have been accorded. Although none of this guarantees your credibility or trustworthiness, it does convey a sense of who you are and where you have been. That often brings a measure of comfort to the grantmaker, especially if the two of you have shared similar experiences. An increased comfort level makes a grantmaker more receptive to the idea that you could make a good partner.

The guerilla fighter needs full help from the people of the area. This is an indispensable condition.4

CHE GUEVARA, GUERRILLA WARFARE