CHAPTER TWO

WHERE THE MONEY IS: CONDUCTING EFFECTIVE PROSPECT RESEARCH

[Strategy is] a plan of action designed in order to achieve some end; a purpose together with a system of measures for its accomplishment.

REAR ADMIRAL JOSEPH C. WYLIE, MILITARY STRATEGY: A GENERAL THEORY OF POWER CONTROL

So far, we have reviewed the basic principles of guerrilla grantsmanship: viewing grantmakers as customers, showing them deference, and addressing their basic priorities and concerns, while always operating with realistic expectations and being able to demonstrate the financial support of others. We also noted that grantmakers have either direct or indirect authority to make grants, and that they may be approached by the grantseeker directly, indirectly, or through paid access.

Even this amount of knowledge probably gives you a significant tactical advantage over the other grantseekers with whom you compete. It is part of the proper mind-set needed to begin developing a strategy and preparing your approach to the grantmaker. But there is more to learn; getting ready to seek grants entails a comprehensive and intensive planning process. This and the following chapter outline the steps to take in developing the kind of relationships that lead to grant awards. They will allow you to understand in advance, before you pick up the phone to begin your first conversation with a future funding partner, several important considerations:

- What type of transaction you are proposing to enter into

- What kind of dynamics this transaction will involve

- Who some of your possible funding partners are

- Who can open the door, and how

- What key facts you should present in your first encounter and which strategic approach is best

What Type of Transaction Will This Be?

As you embark on a grantseeking venture, ask yourself what type of transaction you hope to complete. There are two kinds, and most people new to grantseeking fail to reflect on the critical differences in dynamics, motivation, and strategies between the two.

In Scenario A, the most common type of transaction, the grantseeker initiates the contact and seeks support. Such situations include:

- Development of a new project, service, or organization

- Meeting an emergency need or completing a stalled project

- Meeting an ongoing need

From now on, these will be referred to as Situations One, Two, and Three.

The other type of grantseeking transaction, Scenario B, occurs when the grantmaker initiates contact after identifying a problem or opportunity and deciding to invest in the area. The funder makes it known that a new source of support is available for those who offer solutions to the problem or ways to take advantage of the opportunity. In such cases, the grantseeker must decide whether it is wise to enter into a joint venture as defined by the grantmaker.

In both Scenarios A and B, the funder, who has the money, is more powerful than the grantseeker. However, the dynamics of the two kinds of deals are different, as are the opportunities available to the grantseeker.

If you are a Scenario A grantseeker, you think of the funder primarily as an avenue to securing the support you need or want. In building your case, you must rely on general information about the grantmaker's mission and demonstrate that fulfilling your need will also carry out that mission. Your position, however, is weak because you initiate the contact, build your case based on inferences about the grantmaker's interests that may or may not be accurate, and can clearly express only your own need.

You can strengthen your position by drawing the most accurate inferences possible and by emphasizing that support for your project will also benefit the funder. To the extent that you persuade the funder that you share certain goals and objectives, you come closer to a position of psychological parity or partnership; to the extent that you concentrate on your own need, your position grows weaker and you become a mere supplicant. For this and other reasons, get out of the habit of thinking, talking, and writing in terms of your organization's needs. You will be more effective if you focus on the needs of those you serve—your constituents, the community, and society. The difference is more than semantic; your organization exists not to solve its internal problems and perpetuate itself but to serve people.

Under Scenario B, on the other hand, responding to a funder's announcement of an opportunity can establish you as a potential partner with the funder, one that can help accomplish a task, solve a problem, or address a need. Successful grantseekers in such circumstances make the case that their projects will indeed accomplish the task, solve the problem, or address the need identified by the grantmaker. The goal is explicit, so you need not depend on inferences about it; and though the funder's financial resources make the deal viable, you are in the relatively strong position of being able to provide something she has publicly said she wants. As you are responding to a request, you are by no means a supplicant.

What Kind of Dynamics Will This Transaction Involve?

Once you have determined the kind of deal you are contemplating, you need to understand what dynamics are involved before you can develop an optimal strategy for success. Given the two scenarios and three situations defined above, here is an outline of the basic dynamics of each.

Scenario A: Organization Seeking Support

If you are seeking support for whatever reason, you are aware of a need and have in mind a way it can be met, and thus your goal is to identify a funder whose philanthropic or business purpose is compatible with supporting the activity you propose. Therefore, in making your approach, you must emphasize how this activity can help fulfill the funder's own mission. Discovering that mission is a matter of research: you may best be able to do it by reviewing previous grants the funder has made and speaking with the grantees about their projects.

Some of the strategic decisions you make will be determined by the situation—that is, the specific type of support you are seeking.

Situation One: Developing a New Project, Service, or Organization. This is the most common situation in which grantseekers pursue support. Perhaps, now and then, you have sat at the kitchen table late at night asking yourself, “Wouldn't it be neat if we could . . . ?” If so, your thoughts might be similar to those of nonprofit executives who asked themselves questions such as these:

- Wouldn't it be wonderful if parents of retarded children didn't have to worry about what might happen to their children after they die?

- Wouldn't it be great if welfare mothers had a network of friends, rather than being so isolated?

- Wouldn't it be a blessing to offer hospice care for families with terminally ill children?

- Wouldn't it be nice if inner-city kids could do something productive in the summer instead of hanging out and getting into trouble?

In reality, each of these questions did lead to the development of a new program or service, and in each case it was appropriate to seek external funding for the start-up costs. The nonprofit executives who asked themselves these questions sought support from funders with whom they already had established relationships, and they were all awarded grants.

Some problems can be addressed by developing a project, a specific set of activities to be accomplished within a specific period of time. More often, problems require the development of a program, a specific set of activities that will continue indefinitely but may require external funding only to get them started. In other cases, a project or program to counter a problem is already in place, but a new service may be necessary—that is, a new way to serve existing clients or a way to begin serving a new group of people. On occasion, a whole new organization may be needed when none exists to offer the services people need; this is fairly rare but does happen, as in the mid-1980s when AIDS was first diagnosed and patients and their families needed new forms of support.

Project, program, service, or organization: all have one-time start-up costs. Staff must be recruited and trained; facilities must be located and equipped; communications materials must be produced. And initial operating expenses must be funded until cash flow from other sources is sufficient.

Start-up costs are often the easiest kind of support to secure from philanthropic funders. Many foundation people consider themselves the venture capitalists of the nonprofit world, and by providing start-up support they can legitimately take credit for enabling a new enterprise to begin operation. Furthermore, if you are seeking start-up funding you usually have a strong position: you often will be perceived as bold, creative, and innovative.

Situation Two: Meeting an Emergency Need. Sometimes unanticipated events cause an emergency. Advance planning or insurance can safeguard organizations against many kinds of emergencies, but nonprofit executives may still be forced to make difficult choices that leave their organizations vulnerable. For instance, an organization whose income stream changes may find itself in a cash-flow crunch. If sound planning and effective fundraising programs are in place, the organization will have a cash reserve or an endowment fund that earns enough unrestricted income to meet the challenge. But just as many small businesses are undercapitalized, most nonprofits are underendowed and thus vulnerable to cashflow crises.

Emergencies frequently have to do with capital needs: boilers blow up, roofs begin to leak, and so forth. Adequately funded and well-managed organizations set aside plant funds for such circumstances, but other organizations may be less well prepared. Individual projects are also vulnerable; good managers may start with sound plans and adequate resources, but unexpected conditions can change things. Building projects, for example, can be stalled by any number of conditions beyond one's immediate control—weather, labor problems, interruptions to income streams, unforeseen but necessary design changes. The need to complete a stalled project can constitute an organizational emergency.

For that matter, nonprofit executives may take risks that put the organization in a dangerous position. When the president of a college or the headmaster of a secondary school is forced to spend more than usual to recruit extraordinary talent, for example, faculty or scholarship funds may be depleted. If these funds are not promptly and fully replaced, the school may find itself short of critical resources down the road.

Whatever the circumstance, a single organizational emergency can have widespread ramifications and turn into a full-blown disaster. You may seek philanthropic support to meet the need, but the dynamics of this situation are very different from those involved in seeking support for a new project, service, or organization. Most critically, little benefit accrues to the funder who provides money to fix your roof or replenish your scholarship funds. To secure support in such a situation, you need to prove to your grantmaker that your organization has been neither incompetent nor imprudent. At the very least, you need to show that you have put into place strategies for staying out of trouble in the future.

Situation Three: Meeting an Ongoing Need. Although some activities undertaken by nonprofit organizations become self-sustaining, others never reach that desirable state. Ticket revenues, for example, may never provide all the funds necessary to mount a ballet or concert season. Client fees may never cover the cost of counseling the poor. Tuition alone will never pay the tab for higher education.

Many well-managed nonprofits try to compensate by adding revenue-generating ventures to their charitable programs, but rarely do these produce sufficient funds to balance the financial picture. So nonprofit executives often look to philanthropic sources for continuous support, even though most grantmakers prefer to make one-time or short-term commitments.

Some foundations, however, are sympathetic to certain causes, such as helping the poor or creating art. They understand that it is inherently difficult or impossible to manage such activities in a way that is profitable or even self-sustaining. If your organization fits this description, these are the kind of grantmakers to seek out.

Scenario B: Grantmaker Seeking Projects

When the grantmaker rather than the grantseeker wants to initiate a project, the dynamic of the relationship between the two is very different. For the foundation executive or legislator, the purpose is to address a problem by investing in experimental solutions. For the nonprofit executive, it is an opportunity to secure new money.

In this scenario, the key is to determine whether you have a realistic chance to compete successfully for an award. The most important factor here is the way you learn about the program. Foundations and government agencies generally announce new programs by disseminating a request for proposals (RFP) or a broad agency announcement (BAA). During the program planning process, well before these documents are issued, program officers usually have informal conversations about their plans with people they know and trust—often nonprofit executives who are current or former grantees. If you are among the people a funder calls to discuss a new program, you have already established a relationship with a high level of mutual trust and respect and are in an ideal position to submit a winning proposal.

Funders may also convene formal meetings of advisory groups to discuss the development of a new program. The people who participate in these learn about the opportunity first and may even contribute to the shape and details of the program. Again, if you are part of the planning process, it's very likely that any proposal you submit will receive funding.

Once the program concept is set, the funder distributes the RFP or BAA. Naturally, the only people who are on the mailing list are those with whom the funder has had some contact, and the nature and extent of your contact will determine to what degree your position is enhanced. If you once called an agency and asked to be put on the mailing list, that won't increase your chances of success much. On the other hand, if you are on the mailing list because you have received grants in the past, and your previous projects were successful, then your chances of succeeding again will be quite high.

The RFP or BAA often includes a notice of a public meeting or a series of workshops where representatives of the grantmaker will discuss the opportunity from the funder's point of view. If you attend such a meeting or workshop, you will have an opportunity to meet program staff and discuss the program (but not your specific project) with them. If this is your first meeting with the funder and you make a positive impression, it will increase your chances of winning an award.

By attending these meetings, you may learn that the project you have in mind has a low probability of being funded. Because it takes considerable time, energy, and resources to develop a full proposal, it is often worthwhile to learn enough to make a strategic decision not to submit one.

Invariably, many people who receive the RFP or BAA are unable to attend the workshops. Others receive the documents after the workshops have been held. If you don't attend a workshop, for whatever reason, your chances of winning an award will be dramatically reduced—not only because you have missed an opportunity to learn about the program but, even more important, because you have missed a major opportunity to meet and begin your relationship with the funder.

Many people read RFPs or BAAs only after hearing about them from others who are nice enough to share the news. But if you learn about a new program from a friend or colleague and you have no current relationship with the funder, your chances of winning an award are probably under 10 percent. You've gotten the news relatively late in the process, so you will have less time than many others to develop a relationship with the funder, and to work on a proposal before the deadline for submission.

Most nonprofit executives new to grantseeking have no idea what factors increase or decrease the likelihood of winning. They take the announcement at face value, becoming extremely enthusiastic and entertaining unrealistically high hopes. This may be natural, but to avoid later disappointment, the first thing to do when you learn of a new opportunity is to realistically assess the likelihood of winning based on the way you learned about it. If after doing so you honestly believe you have a reasonable shot at securing funding, then you need to answer the following three strategic questions to help determine whether the opportunity is really worth pursuing.

Is the Goal of the Funder's Program Compatible with the Mission of My Organization? Grantmakers usually state the program goal in the RFP or BAA, but not always in terms that help you make this assessment. If you are at all unclear about the funder's goal, call the funder and discuss it. This is a perfect opportunity to begin a relationship: asking a question that demonstrates that you understand the system and respect it.

If you determine that the funder's goal and your organization's mission are not compatible, do not submit a response no matter how tempting the prospect of bringing in new money may be. If you were to actually win an award in such a circumstance, you would have to implement the unsuitable project or refuse the funds. Either way, you create a problem for yourself.

On the other hand, your mission may be compatible with the funder's goals; if so, consider the following questions:

Is the Project You Have in Mind a Means to the Funder's Ends? To answer this question, you must make a distinction between means and ends. Many nonprofit executives new to grantseeking think that mounting a project is an end in itself, but that is not the case. To determine project ends, you need to step back and look at project outcomes—how the world will be different after your project is implemented. Then you must reflect on the ends sought by the funder and determine whether the two are compatible.1 If they are, proceed to the following, final question in your preliminary assessment.

Do You Want to Enter into a Joint Venture with This Particular Funder? When you respond to an RFP or BAA, any funding you receive will become the glue that binds you to the funding organization. Accepting a grant represents a legal agreement to conduct the activities described in your proposal. So if you have any doubts about your plans, your intentions of following through on them, or your desire to enter into a long-term relationship with a particular funder, you need to face it early on—not after you receive an award.

Only if you can answer all three of the above questions in the affirmative should you proceed to develop your strategy, the first step of which is to conduct research to identify possible funding partners.

Who Are Some of Your Possible Funding Partners?

Finding funding partners requires both research and reflection. In grantseeking, part of your research will focus on locating people who can help you with this process.

Scenario A: Organization Seeking Support

Like many other activities, gathering information about funders is a matter of studying the three E's: elegance, ease, and economy. Elegance refers to the quality of the work, ease refers to the effort it requires, and economy refers to the cost. Because you must always choose between investing time and investing money, you can have two E's, but never all three. If you have more time than money, you can do it yourself. If you have more money than time, you can hire someone to do it for you. Elegance varies with the amount of time or money available.

Conducting Your Own Research. If you choose do-it-yourself research, one organization is a splendid resource: the Foundation Center. This nonprofit group collects published information about private sources of philanthropic funding and some information about public funding. It has national collections in New York City and Washington, D.C., regional collections in Cleveland, Atlanta, and San Francisco, and local collections in 190 libraries throughout the United States (see Resource A).

At the national and regional Foundation Center libraries, free orientation programs are available for new researchers, and Foundation Center staff members often visit local collections to conduct information sessions. Even if no video or personal orientation is available at your site, all Foundation Center collections have written materials that outline the research process and suggest places to start.

In Chicago, the Foundation Center is affiliated with the Donors Forum of Chicago Library, which is sponsored by a regional association of grantmakers in the Greater Chicago metropolitan area.

Working with Consultants. Just as you may pay for access to grantmakers if you can't identify sources of direct or indirect access, you may also pay for research. If you choose this option, you can hire either a research firm or an individual.

If you prefer a firm, in most locations you can select between nonprofit services and commercial ones. The most expert nonprofit service currently available is the Foundation Center. Its national headquarters employs five full-time researchers who will search computerized databases for a relatively modest fee. Some public libraries also offer fee-based research services. If available, as they are in most cities, commercial research firms can access national databases containing information about publicly held companies and their officers. Of course, to work cost-effectively with a research firm you must formulate your questions carefully. At the very least, you need to have a fairly clear idea of the kind of information you are seeking.

In working with research firms and computerized databases, the most serious limitation is the loss of the “serendipity factor;” computers ignore information that is proximate—connected by tenuous but potentially fruitful links. On hiring a research firm, interview the person who will actually conduct the research to make sure he understands your needs. Your researcher should be willing to take an occasional risk, and even to do some nonlinear thinking.

If you prefer to work with an individual, two national organizations can provide information about people in the fundraising profession: the National Society of Fund-Raising Executives (NSFRE), based in Arlington, Virginia, and the American Association of Fund-Raising Counsel (AAFRC) in New York City. NSFRE is the professional association for people involved in managing fundraising programs for nonprofit organizations. NSFRE currently has 125 local chapters and more than 17,000 members, and is still growing rapidly. The NSFRE Directory identifies those members who do at least some consulting work. AAFRC is the professional association of fundraising consulting firms. Most of these firms concentrate on providing counsel to organizations conducting major capital campaigns. Large consulting firms have little interest in grantseeking, as it is difficult to generate enough such business to keep their staffs busy and the fees generated are relatively modest. An AAFRC member firm, however, might be able to refer you to an independent consultant in your area who specializes in grantseeking.

A few words of caution: anyone can legally claim to be a fundraising consultant, and a few unscrupulous individuals periodically cause credibility problems for the entire profession. So be sure to exercise care in retaining the services of a consultant. Like other professions, such as accounting and financial planning, the fundraising profession has adopted a certification process. A professional who has met the standards administered by NSFRE is permitted to practice as a certified fundraising executive (CFRE); you might feel more confident if you select a consultant who has earned the CFRE designation.

Hiring somebody to conduct your research is like hiring anyone else: the clearer you are about your expectations, the more likely you are to get the results you want. But some nonprofit executives new to grantseeking think they can simply hire someone and instruct them to get grants. It won't work. No one can get grants for someone else, because grants come about through relationships between grantseekers and grantmakers. You can hire a consultant to fulfill some relationship functions, or to provide occasional interaction. But there is simply no substitute for a real relationship—that curiously complex, ongoing series of shared experiences.

Defining Your Needs. Whether you conduct your own research or retain someone to do it for you, it will be most productive if you begin with a clear idea of what you want or need. Just as novices may believe in the myth that they can hire someone to get grants for them, another form of wishful thinking is the belief that somewhere out there is a “magic list”—that if they can only identify the right foundation prospects through library research and send each a cogently written proposal, one or more checks will arrive by return post. And once in a great while, if a grantmaker is looking for new grantees or competition is light or the moon is in the right phase, this may actually happen. However, it doesn't happen much more frequently than a hole-in-one in golf or winning the lottery; don't count on it. It is far better to concentrate on identifying key individuals in the grantmaking process and developing relationships with them. Though this requires more time and dedication than merely developing a list and zipping off proposals, the investment of time and energy will pay off in the long run.

Where do you start? Two ways of doing research can lead more or less directly to identifying your best prospective funders. First, you can take advantage of the information readily available in your organization's records; and second, you can select those grantmakers whose mission and values most closely match those of your organization.

Reviewing your organization's internal records is the quicker of these two. Every nonprofit has a board of trustees, and most have a base of current donors, both large and small, which includes individuals, foundations, and corporations. Most organizations also maintain records of correspondence with foundations and corporations; from this you can learn who asked for previous grants and who was responsible for making them.

Depending on the type of organization you work for, you may also have records of individuals who benefited from or participated in your activities. Hospitals, for example, have physicians and grateful patients, and patients have relatives. Colleges have faculty, alumni, and parents. Social service agencies have clients, and clients have relatives. Presenters of performing arts programs have subscribers and audience members. In addition to the individuals currently affiliated with your organization, consider those who were affiliated in the past. There may be a reservoir of goodwill among family members of the people who were directly served. (There may also be reservoirs of ill will; if so, it's best to know about them.)

By going through all these institutional records, you can quickly and easily develop a list of people who know your organization and may be inclined to assist you with your grantseeking efforts. The other way to identify those who might help is to select grantmakers whose mission and publicly declared values match those of your organization. Consider the following factors as you put together a list of criteria for selecting these grantmakers.

Geographic Location. Location is almost as important in fundraising as in real estate. For most funders, it is the single most important criterion in awarding grants. Those in the private sector generally prefer to spend their money close to home. Individuals and families like to sponsor organizations in the community in which they live; corporations want to support organizations in the communities where they do business; and community foundations, by charter, support only organizations within a particular geographic area.

National foundations, on the other hand, usually try to distribute grants to all major regions of the country. They often strive to make awards to organizations that represent all kinds of communities, from densely populated urban centers to sparsely populated rural areas. Government funding also usually has a wider focus. The most common consideration in public funding is to distribute grant awards as equitably as possible throughout the political units (states or counties); less common is the targeted public program, in which grant funds are distributed to accomplish specific purposes in specific areas.

Although there is nothing you can do about your location, knowing the funder's geographic priorities can help you assess more realistically your odds of succeeding in a national or statewide competition.

Areas of Interest. It may seem obvious, but keep in mind the area in which your organization is working: health care, social services, the arts, and so forth. A program officer recently said that over half the proposals received by her foundation come from social service agencies, which her foundation does not support. Clearly, many grantseekers do not make sure there is a match between the work they do and the kind that the foundation or government agency supports. Sometimes, however, thinking about your organization's work in a creative way may help you identify more potential sources of support than you otherwise might consider.

When probing for matches with funders' areas of interest, research conducted by people rather than computers may well be superior, so doing it yourself may be more productive than hiring someone who is less familiar with your programs. If your project is relevant to several disciplines, it could attract a variety of funders.

True Story

The CEO of a social service agency with a preschool program became aware that many youngsters in his program were being abused at home. He wanted his staff members to be able to help the children and their parents stop the abuse. So the CEO and his staff developed a new project.

A child psychiatrist who specialized in dealing with abuse visited the center regularly. The psychiatrist met with and began treating the children in greatest distress. The psychiatrist also provided training sessions to raise the staff's awareness of child abuse, and taught laypersons strategies for dealing with these situations.

For this project, the social service agency was eligible to seek grants from funders with a variety of interests, including domestic violence, mental health, preschool children, families living in poverty, and education and training.

Thinking broadly and creatively about the area in which you are working may open new doors.

Type of Support. Most funders are very clear about the types of support they will provide. The basic categories are:

- Project funding—support for a clearly defined set of activities designed to accomplish a specific purpose within a specific time

- Endowment funding—financial assets that are to be invested to generate income; the income is expended and the principal remains intact

- Capital funding—investment in buildings, land, equipment, or anything else considered part of an organization's permanent physical assets

- Operating support—funding for ongoing expenses such as rent, utilities, and staff salaries

- Program funding—grants that reflect operating support if the program is ongoing, or project support if its duration is limited

Because most funders prefer to support projects rather than operations, grantseekers often go to great lengths trying to disguise operating needs as special projects. This is not a sound strategy as any funder who's been around more than five minutes will easily see through it. It's better to use a straightforward approach: make a clear presentation of what you want or need, and proceed to develop the kind of relationship that can lead to the support you seek, even if it might not be immediately available because of the funder's published guidelines.

Range of Grants. The magnitude of the project or need is important in determining which prospects appear promising. In general, the larger the potential grant amount indicated by the funder, the better. Although it is unwise to put all your eggs in one basket, securing two or three large grants is clearly more efficient than going after dozens of small ones to raise the same amount of money. Remember that grants come out of relationships, and you will have to develop a relationship with each and every prospective funder you approach. Each will require time and attention.

People. Once you have selected funders that meet your criteria of location, area of interest, type of support, and range of grants, you can turn to the most important part of the research process: developing a list of individuals associated with the grantmaking organization. This is the heart of the grantseeking process!

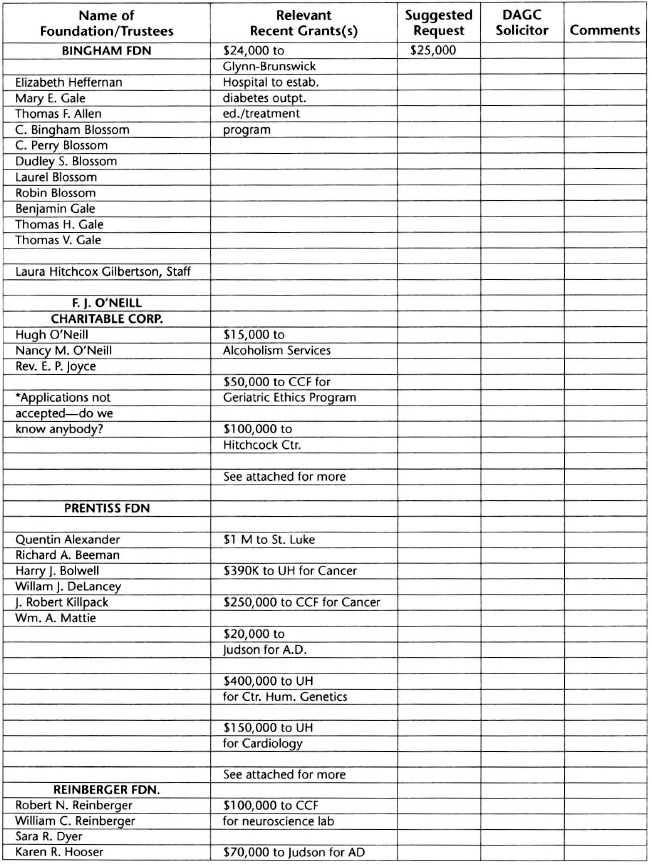

Identifying key individuals is the most important part of any research effort, because your relationships with these people will ultimately determine your success. Your list of key individuals at each grantmaking establishment should include professional staff as well as officers and trustees. Exhibit 2.1 shows one format that many organizations find useful for identifying these relationships.

Reviewing such a list with the trustees or volunteers of your organization who are responsible for raising money can be very helpful. But as it is much easier to respond to a list than to generate one, you will identify many more contacts if you prepare a preliminary version, rather than generating it on the spot by asking your trustees to identify people they know who serve on foundation boards. Furthermore, if you do the review in a group, the dynamics of peer pressure will come into play, and people will be encouraged to sign up as solicitors.

EXHIBIT 2.1. FOUNDATION PROSPECTS FOR THE DIABETES ASSOCIATION OF GREATER CLEVELAND (DAGC).

As you conduct the review, be sure to ask your trustees to provide any information they can, whether or not they intend to contact the grantmaker themselves. For instance, if a trustee knows that a listed individual has the greatest influence on the foundation's decision-making process, it is essential for your organization to know that. If a trustee has information about the personal circumstances of any listed individuals, this can also be helpful in planning your approach. For instance, if a foundation trustee is nearing retirement or going through a divorce, this may affect his financial position or the chances of his responding to a request for special consideration.

Note and transfer to your organization's permanent file all the information gleaned from reviews. Foundation trustees generally serve for long periods, and the information may prove helpful for years to come.

Scenario B: Grantmaker Seeking Projects

When a funder announces an opportunity, the research strategies are different. To decide whether you want to respond to an RFP or BAA, you will need to determine the following:

- What kind of responses will be competitive

- What criteria will be used to separate winners from losers

- How stiff the competition will be

There are three sources of information who may be able to help: representatives of the grantmaker, colleagues who have more insight or experience than you, and consultants who specialize in grantseeking. In general, the closer your source to the grantmaker, the more valuable the information will be.

In evaluating information about a funding opportunity, two caveats are in order. First, be wary of colleagues who discourage you; those who are thinking about preparing a competing proposal are probably interested in reducing the competition.

Second, when considering government programs, bear in mind the appropriations game, played as follows: In Year One, an agency issues an RFP for a program funded at the $50 million level. The agency receives applications from 1,000 organizations requesting a total of $5 billion, but makes only ten grants averaging $5 million each. Lots of applicants are disappointed, but when appropriations time rolls around again the agency will be able to demonstrate sufficient interest in the program to justify an increase in its appropriation for Year Two. Legislators, interested generally in bringing more government dollars to their constituents and specifically in assuaging the feelings of those who were disappointed the first time, may be inclined to appropriate $ 100 million or more on the second go-round.

For these reasons, government program staff often encourage virtually every organization to prepare and submit a proposal. It's not because we live in a great democracy where every organization has an equal chance of securing public funds, but because staffers want their agency and its programs to appear important so the agency can grow and they can keep their jobs. And one way to demonstrate the importance of a program is to generate requests for many times more dollars than are available.

Most funding opportunities, public or private, are highly competitive. Don't waste your time developing a proposal if you see any indication that you might not stand a good chance of winning. You will be far more successful if you spend your time improving the odds by building relationships and then submitting proposals when you know your chances are good.

We should be informed of all aspects of the terrain that are disadvantageous to us ... such as narrow roads, river crossings, circuitous routes for avoiding these river crossings and narrow roads, etc.

MAO TSE-TUNC, BASIC TACTICS