CHAPTER SEVEN

PREPARING AND SUBMITTING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL

The fundamental principle is that no battle, combat, or skirmish is to be fought unless it will be won.

CHE GUEVARA, GUERRILLA WARFARE

As mentioned earlier, the art of grantsmanship is permeated by myths. Two of the most dangerous ones have to do with proposals.

Myth Number One: When you want to get a grant, the first thing to do is to write a proposal.

Myth Number Two: The quality of the proposal determines whether a grant is awarded.

By now, you know that when you want to get a grant, the first thing to do is to begin a dialogue with a grantmaker; furthermore, the quality of your proposal is less important than the quality of that dialogue and of the relationship on which it's based. In real life, well-crafted proposals are often turned down and even poorly crafted proposals sometimes result in grants. Not that proposals are unimportant, but you need to keep them in perspective.

Preparing a formal proposal requires a significant investment of time, energy, and resources. Before you begin, therefore, assess your chances of winning an award and decide on that basis whether it is worthwhile to submit a proposal. Go forward only if you are convinced that your chances are good. Otherwise, focus on opportunities that are more promising. Remember, you aren't making this decision blindly; you have numerous opportunities to pick up promising or discouraging signals in your conversations, correspondence, and meetings with the grantmaker.

In this chapter, we define the conditions under which it is worthwhile or not worthwhile to prepare a proposal and explain how to obtain maximum benefit for your organization from the process of proposal preparation. Many people see the process as requiring specialized skills and arcane knowledge, but it is really quite straightforward, albeit very time-consuming.

Contrary to popular belief, proposals for government funds are not fundamentally different from proposals to private foundations. Though it is true that government agencies often have more technical requirements than private foundations, nothing that any government agency requires is beyond the grasp of a well-educated layperson. Remember, if public money is being awarded, it is, in a sense, your money. As a taxpayer, you have as much right to go after it as any other taxpayer. You can demand that the instructions be explained so that you understand them!

Seven Preliminary Scenarios

Before delving into the details of proposal preparation, let's review seven scenarios that represent the range of preliminary exchanges between grantseeker and grantmaker and suggest the best course of action for each in regard to the preparation of a proposal.

When Is It Worthwhile to Prepare a Proposal?

There are three circumstances in which it is worthwhile to prepare a proposal:

- When you have reason to believe that it will result in the immediate or eventual awarding of a grant

- When you are looking for a way to expedite the planning of a project

- When you wish to open a dialogue and the awarding of a grant is secondary

In the first case, where obtaining a grant is your highest priority, one of three positive scenarios may come into play.

Scenario One: The Optimal. The optimal scenario is to be told by your grantmaker that funds have already been earmarked for your organization and that if you prepare and submit a proposal documenting the agreement you have reached verbally, an award will be made. This is not an everyday occurrence in the world of fundraising, but it does happen (more often with government funding sources than private ones). When it happens, rejoice—and then get to work on the writing!

Scenario Two: High Level of Promise. If the grantmaker initiates a conversation in which you are clearly invited to submit a request, your chances of being awarded a grant are high and you can approach the task of preparing a proposal with great optimism.

Scenario Three: Good Level of Promise. The odds of your being awarded a grant may also be favorable if you initiate the contact and the grantmaker responds to your inquiry with enthusiasm, inviting you explicitly or implicitly to submit a proposal.

When obtaining a grant is a secondary concern, two other positive scenarios are possible.

Scenario Four: Expediting the Planning Process. The fourth scenario prevails when your highest priority is to expedite your internal planning process. An imminent proposal submission deadline may be one of the best tools in your motivational arsenal, helping you to marshal your resources and get people moving quickly. As Boswell's Johnson pointed out, “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”1 The same may be said of an imminent proposal deadline.

Scenario Five: Opening a Dialogue. You may find yourself in a situation where you recognize that you need to build a relationship with a grantmaker but it proves impossible to make the initial contact directly by phone, preliminary letter, or personal visit. You may feel, and it may indeed be the reality, that the only avenue open to you is to submit a proposal. The odds of your receiving a grant in response to a “cold” proposal are slim, but if you view a proposal as the opening gambit in a dialogue you hope to establish—and if on this basis alone you can afford the time, energy, and resources required to prepare it—it may be worth proceeding.

When Is It Not Worthwhile to Prepare a Proposal?

It is generally not worthwhile to prepare a proposal if you find yourself in one of the two following situations.

Scenario Six: Unenthusiastic Response. Let's say that you initiate a contact with a grantmaker and describe your idea either in a conversation or in writing, and the response lacks enthusiasm and interest. In this case, it is probably a waste of time to prepare a proposal, as the chances of being awarded a grant are very slight.

Scenario Seven: No Prior Contact. If your sole purpose is to secure a grant from a particular funder at a particular time, and you have had no conversation or personal correspondence with her, it is probably not worthwhile to submit a proposal.

There seems to be no consensus on what the ratio is between proposals submitted and grants awarded, but various scholars estimate it at somewhere between one in five and one in twenty. Whatever the exact number, we know that grantseeking is a highly competitive activity and that the vast majority of the proposals that result in awards are submitted by people who have had direct contact with the grantmaker.

Preparing a Grant Proposal

If it makes sense to submit a proposal but you have never successfully done so before, you may well be uncertain how best to proceed. The balance of this chapter outlines the steps you should take to obtain the greatest benefit from the process and to maximize your chances of success.

First, the good news: before you embark on the preparation of a proposal, you will have already completed the first step. That is, you will have emerged from the creative struggle of figuring out how to solve a problem or meet a need. You will have generated an idea. This is far and away the most challenging and exciting part of the entire process. Now the bad news: from here on, it is mostly a matter of hard work. However, the method outlined here will enable you to carry out the necessary tasks as efficiently and productively as possible. We discuss in detail the kinds of tasks that must be completed by you, the person in charge of the process, as well as those that can or should be completed by colleagues or other members of your staff.

Sculpting Your Project

The average project is conceived on a fairly abstract level and discussed in a conceptual fashion with grantmakers and perhaps with others. But now it is time to concentrate on making all aspects of the project as concrete as possible.

You might find it helpful to think of this process as mental sculpting. You have the basic materials and a general idea of what you want the finished product to look like; now you will shape the project and add detail to prepare it for exhibition before a select, sophisticated, and demanding audience. On a mundane level, of course, your purpose is to describe in a persuasive fashion the activities that will be part of your project; but even this is a creative process, so bring your creative faculties into play. If you are a verbal thinker, you can develop a list of phrases to describe your project. If you are a visual thinker, you can envision a series of scenes. If you are familiar with the technique of storyboarding, you can use it to illustrate how you believe events will unfold as your project becomes a reality.

Very few grantseekers get dressed, go to their offices, sit down at their desks, and sculpt their projects. The process requires less creativity than generating ideas, but your subconscious can still play a role. You can mull over your project while you do other, less mentally taxing things such as showering, driving, or cooking (but please be careful when mulling while driving or cooking!). Your project will develop organically, evolving as you live with the idea until one day you recognize its proper shape and direction. Given the evolutionary nature of project development, you will be able to carry on other activities that will advance the preparation of your proposal during the days or weeks it takes to reach the final state.

Examining the Criteria for Eligibility

As indicated earlier, the first task that can be conducted on a preliminary basis is determining whether your organization meets the criteria for eligibility established by the grantmaker.

Some requirements, such as tax-exempt status, are almost universal. Only about 5 percent of all grantmaking organizations award grants to individuals. The other 95 percent require that recipients be qualified by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as charitable tax-exempt organizations, according to Section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.2 Other requirements are peculiar to specific funders. Some, for example, require that an organization be in operation for three years before it can be eligible.

Planning the Work

Once you have determined that your organization is eligible for a grant, review the funder's proposal guidelines and map out a plan for preparing all the sections that will eventually be assembled into the document you submit.

Word processing, spreadsheet, and project management software may make it easier for you to do the work in the sequence that makes the most sense and then cut and paste it all together in the order in which it needs to be presented. What information do grantmakers request? In what order do they want it presented, and how much detail do they want to see?

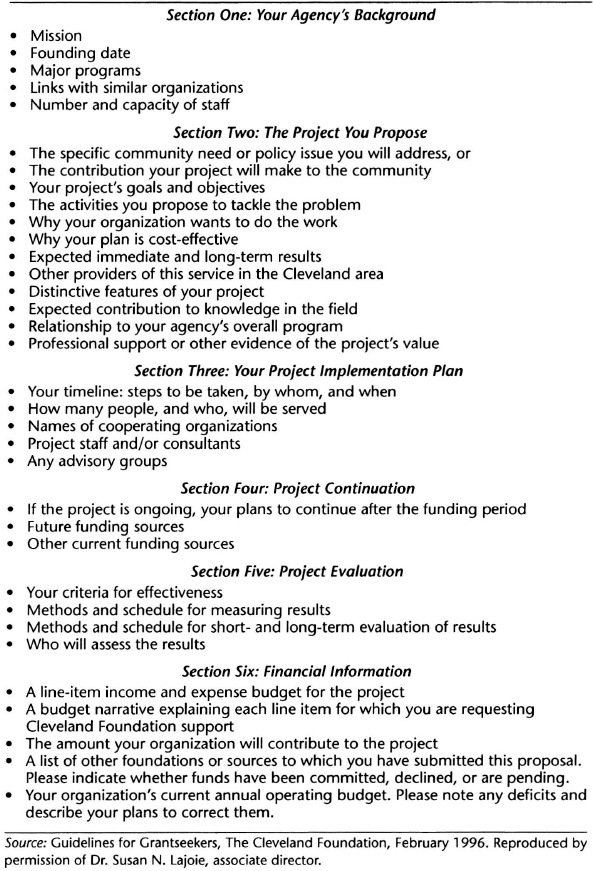

The guidelines published by The Cleveland Foundation, the oldest and second-largest community foundation in the United States, are fairly typical (see Exhibit 7.1).

EXHIBIT 7.1. PROPOSAL GUIDELINES OF THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION.

The order of information requested in Exhibit 7.1 may be quite different from the order in which you do the work of developing it. You should strongly consider preparing the sections in the following order:

- Your agency's background (Section One)

- Project implementation plan (Section Three)

- Financial information (Section Six)

- Project evaluation (Section Five)

- Project continuation (Section Four)

- The project you propose (Section Two)

The reason for this order is that over a period of several days, weeks, or even months, you will be cogitating about your project—which must be completed before you approach the sixth and final task. In the meantime, you can begin working on the other sections of the document. With the order recommended here, each task will lead organically to the next, and the final document, once assembled in the order the grantmaker requests, will flow and be both cogent and compelling.

Task One: Your Agency's Background

As you assemble the information listed in Section One of Exhibit 7.1 (describing your organization's mission, programs, staff, and the like), you can also be collecting key documents that grantmakers often require as appendices or enclosures:

- Letter from the IRS designating your organization as tax-exempt

- List of members and officers of your board of trustees, including their business affiliations and positions

- Your current annual report

- A current financial statement, preferably audited

- Job descriptions of project personnel

If this is the first proposal your organization has submitted, or the first one in a long time, you can help your organization by setting up a grantseeking file. Place in it copies of all the documents you assemble so they will be readily available to you and your colleagues in the future. If, on the other hand, your organization has submitted successful proposals in the past, and only your involvement is new, you may be able to take a shortcut: update information in the grantseeking file that is no longer current, and simply appropriate the other information.

At this stage, you also need to start working with people outside your organization on at least two issues that will be fleshed out later: future funding for the project, and (if the project is collaborative) the nature of the partnership and how it will work.

Future Funding Partners

You may have already given some thought to the long-term financial viability of the project, but many grantseekers do not think about this until their grantmaker insists on it. The earlier you figure out how the project will be sustained after the grant period, the more attractive your project will be to prospective investors and the more likely you will be to secure both the start-up and continuing support you require. If future funders are closely involved in the planning of a project, they are more likely to continue their involvement downstream.

Therefore, if you haven't already done so, now is the time to begin building good relationships with prospective permanent funders, sponsors, and customers. You should inform these people about the plans you are developing, and build their interests into your planning process. This requires an investment of time and energy, but the results it can produce are worth it.

Collaborating Organizations

Your project may involve partner organizations that collaborate on your grantseeking venture and will provide service when the project is implemented. If so, you have probably established some kind of contact with them and inquired in general terms about the possibility of working together. Now it is time to firm up your plans for collaboration. You need to meet with at least one representative of each potential collaborative partner to determine the role each is interested in undertaking and the level of commitment each expects to make.

Developing collaborative relationships is usually worth the time and energy it requires, as many grantmakers today prefer to support collaborative efforts rather than single-organization projects. These funders maintain that collaboration is generally more efficient and more cost-effective than the alternative because they avoid duplication of effort. On the other hand, it usually makes the project planning and organizational requirements far more complex; dealing with multiple sources of information and multiple administrative approvals may make the process seem not just arithmetically but geometrically more complex. Plan accordingly.

Funders today also have rising expectations about grantseekers' advance planning and commitment to collaboration. As recently as a few years ago, some funders accepted letters of support—expressing little more than hearty best wishes—as documentation of involvement. Now, however, most require contracts or at least firm, formal commitments contingent upon the receipt of funds. When organizational resources are being committed, of course, appropriate authorization is required. This almost always involves a good deal of negotiation, which naturally takes time. So if your project involves one or more collaborating organizations, you cannot afford to defer discussions on how the arrangement will work. “Fudging” the details in your grant proposal is no longer an option.

Task Two: Project Implementation Plan

By this time, the evolutionary process of sculpting your project should have produced a list of activities or a series of scenarios. With this information in hand, you can move on to the next task: your project implementation plan.

A method I have developed to accomplish this is to create what I will call a “timeline matrix.” In the process of constructing this grid, you will develop the information on the project timeline requested in Section Three of Exhibit 7.1. You will also develop much of the budget information requested in Section Six. In short, you will answer all of the subquestions involved in these megaquestions: Who will do what to whom, with what, at what cost, and by when? How will we all know it's done and how effectively it was done?

To answer these megaquestions, you will need to identify many things.

- All tasks involved in the project

- Who will be responsible for completing each task

- What resources will be employed in completing each task

- What costs will be incurred in employing these resources

- How long it will take to complete each task

- What milestones will indicate the completion of each task

- What measures will be used to evaluate outcomes

- What benchmarks will be established for changes brought about by the project

Developing a Timeline Matrix

Let's say you are developing a marketing project for a performing arts organization, and one activity will be an advertising campaign. You could construct a timeline matrix to spell out exactly how this would be accomplished. First, list all the questions the timeline matrix will address:

- What media will be used in the advertising campaign?

- How will funds be distributed among direct mail, print, radio, television, billboards, and bus cards?

- Which mailing list or lists will be used for direct mail?

- How will mail be sent—bulk rate or first class?

- Who will prepare the mailing?

- What percentage of the ads in print and electronic media will be free public service announcements as opposed to paid ads?

- Which radio and TV stations will attract the audience the organization wants to target?

- How long will each advertisement be?

- At what time of day will the ads be aired?

- Who will compose the ad copy?

- Who will design the graphics?

- Who will reproduce the graphics?

- What items will need to be printed, and how many copies of each will be needed?

- What size audience can each radio and TV station promise?

- Who will perform in the ads?

- Will royalties need to be paid for music used in the ads? If so, how much and to whom?

- How long a commitment will the organization need to make to the advertising media?

- How will the impact of the advertising be measured?

- How will the organization know that this evaluation was impartial and accurate?

- How will the organization analyze the cost-benefit ratio for future planning purposes?

To answer the questions on a timeline matrix and develop a sound plan, you will need to make some decisions based on incomplete information. If you live in a major metropolitan area, for example, it may not be practical to obtain advertising rates for all TV and radio stations. Therefore, you and your colleagues must come to at least a tentative agreement about the scope of the advertising campaign. As soon as you begin this detailed planning, you must make choices—and, as a consequence, limit the potential of your project.

Many issues will arise as you address the questions you have identified and gather the information you need to come up with answers that make sense. When you have finished constructing your timeline matrix, you will have completed much of the planning that needs to be done for your project.

Allocating Resources to Proposal Preparation

Developing your matrix will be easier if you adopt two strategic approaches to preparing your proposal.

First, make sure you budget sufficient time and resources for the planning and research involved. Before you commit to preparing a proposal, consider how much time and what kind of help is available to you. Factor in this information when deciding whether you can realistically meet the deadline under discussion.

Second, your project will be better planned and its implementation will go more smoothly if you involve colleagues in planning and proposal preparation. You probably have several kinds of colleagues who can help in several ways.

Participating colleagues represent disciplines or functions that will be involved in implementing the project. For instance, if you are planning an educational project, you will want to involve teachers; if you are planning a research effort, you will want to involve researchers.

Service colleagues are those who perform duties that support the mission-oriented work of your organization. The advancement function, for example, includes fund development, marketing, public relations, and planning. Another is the fiscal management function, where colleagues could be consulted if you need to know the value of 10 percent of a staff member's time or the cost of his health insurance. If you need to know how much it will cost to produce a brochure, you would ask someone in public relations to help you develop the estimate.

When you involve colleagues in the planning and proposal preparation process, it helps lighten your personal burden. Beyond that, involving those who will be responsible for implementing and supporting the project confers ownership of the venture on them; people who have been involved in planning a project will be motivated to implement it with greater enthusiasm than those who are merely presented with a fait accompli.

Most assistance in preparing your timeline matrix may come from your own staff, but you may need to go outside your organization as well. Do not hesitate to ask professionals or vendors to develop bids; remember, everyone in business is concerned about developing new business. The ethical approach to securing bids or estimates at this point is to make it clear that you do not currently have funding in hand for the work you are discussing. To encourage a prompt response, point out that the estimate or bid process is part of your fundraising effort, and that once you do have the funds in hand, you will consider that vendor to provide the product or service on which they are bidding.

An ancillary benefit of preparing proposals is that you often gain additional information that is even more valuable than what you set out to collect. In most instances, for example, you will follow sound business practice and secure at least two or three bids for each major product or service involved in your project. In this process, you also learn which vendors are easiest to work with and which professionals best fit the culture and style of your organization. Preliminary contact and working together is like courtship and marriage; a date who exhibits bad table manners probably won't improve merely by becoming a husband, and a vendor who fails to return phone calls promptly as you make initial inquiries probably will not improve by being chosen a project implementer.

The timeline matrix you develop will provide the information you need to prepare two key sections of your proposal: the timeline (for Section Three) and the budget (for Section Six).

Completing the Project Timeline

The timeline identifies each activity within your project, who will be responsible for completing it, and what period of time it will require. The time scale you specify depends on the nature of your project, but whether you outline events on a week-by-week or quarter-by-quarter basis, what counts is to demonstrate that you understand all of these:

- What needs to be done

- The order in which tasks need to be accomplished

- How much time this will take

- What resources will be required

Your proposal will have a more professional appearance if you present this information in graphic as well as narrative form. You can do this fairly easily by using project management software to generate a Gantt or PERT (project evaluation and review technique) chart.

Most grantseekers, by the way, significantly underestimate the time required to complete the activities involved in their projects; a good rule of thumb is to double your original estimate. In your project implementation plan, try to accommodate the operation of Murphy's Law: assume things will go wrong. Most grantmakers have extensive experience with a broad range of projects, and if you underestimate the time required to accomplish your goals, they will see you as naive, a poor planner, or both—and that will discourage them from getting involved with you.

Task Three: Financial Information

Many grantmakers agree that they look at the budget first and give it more rigorous scrutiny than any other part of the proposal. If a grantmaker specifies a format for your budget information, follow it. If no format is specified, a template that seems to accommodate most situations is that of The Cleveland Foundation. Their forms are included as Resource B, and you are welcome to reproduce them.

Before you begin to build your budget, think through all the basic components and parameters of your project:

- Duration of the project

- How much of the project's duration you are asking the funder to support

- Level of resource commitment from your organization

- Number and identity of collaborating organizations and the levels of their resource commitments

- Number and identity of external funders to whom you are applying

- Preferences of specific external funders and any restrictions they will place on the use of funds

Nine Golden Rules

As you plan your budget, you can make it more attractive to funders by applying the nine golden rules of budget building.

Rule One: Keep It Simple. Whenever possible, divide the support you request from multiple sources on a percentage basis. Let's say an expense item costs $1,000 and you have four funders equally capable of supporting it and equally likely to do so. Request $250 from each of the four.

Rule Two: Give Yourself Full Credit. Document as high a level of organizational support as you honestly can. Many people fail through mere oversight to credit their organizations for support in the form of standard business operating costs. Every time someone puts in a new toner cartridge, runs a letter through the postage meter, or staples two pieces of paper together, the organization incurs expenses. Give your organization full credit for providing this support. The more of it you can demonstrate, the more committed your organization will appear and the more attractive your project will be to external funders.

Organizational support can be provided in cash, in-kind services, or both. The expenses involved may be direct or indirect. Commitment is most clearly demonstrated by an allocation of cash for direct expenses, such as compensation for an individual hired specifically to work on the project or the purchase of a piece of equipment specifically for use in it. In-kind services normally include services, staff time, supplies, or equipment provided by the organization without reimbursement. The organization, for example, may donate office space to support the project, or the fiscal officer may agree to oversee the project budget in addition to her other responsibilities.

Indirect expenses may also be incurred. These include overhead or administrative costs that are necessary to the functioning of the project but do not support direct service to clients. Indirect costs are often funded through a donation of in-kind services by the sponsoring organization.

To determine whether organizational resources should be considered cash or in-kind services, ask yourself if you expect a check to be cut specifically for a given expenditure. If you do, that expense probably involves a cash commitment. If you do not expect a check to be cut to cover an expense—such as for 5 percent of the rent or 10 percent of an existing staff person's time—then the commitment is probably in-kind.

Rule Three: Detail the Commitments of Partners. If your project involves one or more collaborating organizations, identify them in your budget and detail their commitment of resources. This demonstrates their level of involvement and their enthusiasm for the project.

Rule Four: Be Specific. Wherever possible, give your budget an aura of specificity by spelling out the number of units and the unit cost before multiplying to come up with a forecasted expense. For instance, if your project involves mailing a newsletter, determine how many copies need to be printed, their unit cost, and the postage cost per copy. Then multiply the unit cost with postage by the number of copies to estimate the total costs of the mailing.

Rule Five: If You Can't Be Specific, Create a Reasonable Fiction. When it is impossible to forecast precisely what something will cost, you can create a reasonable, fact-based fiction. For instance, many funders expect you to be able to forecast exact costs for copying, which is extremely difficult to do. But if you review your organization's expenditures for copying over a recent period, you can probably extrapolate from that to the project you are planning; the number is fictional but reasonable.

Rule Six: Be Prepared for Change. No costs remain static over the life of a project, especially if it lasts more than a year, so allow for inflation and for annual increases in staff compensation. Make sure year-to-year budget projections also reflect any changes in the activities involved in your project; costs increase as you introduce new activities or expand existing activities to serve more people.

Start-up costs should disappear after the first year. Once software has been developed, for example, ongoing maintenance costs can still be included in your budget but the original development cost should be eliminated.

Rule Seven: Nothing Lasts Forever. As discussed previously, though all funders recognize that external support is usually required to get a project up and running, few want to support projects that can never become self-sustaining. Over time, your budget should reflect a diminishing reliance on external funding and an increasing reliance on your own donor base, together with any revenues the project may be able to generate for itself.

Rule Eight: Be Consistent. If you are applying to more than one grantmaker for support, bear in mind that funders are likely to compare notes. They tend to develop their grantmaking strategies in relation to what their counterparts at other foundations or agencies are doing. To maintain your credibility, keep your budget numbers consistent in all the proposals you submit.

Rule Nine: Be Respectful. We all like to think that our organizations are distinctive, even unique, and we are not pleased when others make unwarranted assumptions about us. Grantmakers feel much the same way. Try to respect the limitations of individual funders as you build your budget. For instance, in getting computers paid for, some funders prefer that their money be used to purchase hardware and some prefer that it buy software. If you are aware of such preferences, they should be reflected in the way you build your budget.

Building a Budget: An Example

To illustrate how these guidelines play out in practice, we consider here how one grantseeker built a budget, and the thinking that went into its presentation. You will develop the various sections of your budget in much the same way as you do the proposal narrative: doing the work in one sequence but presenting it in another.

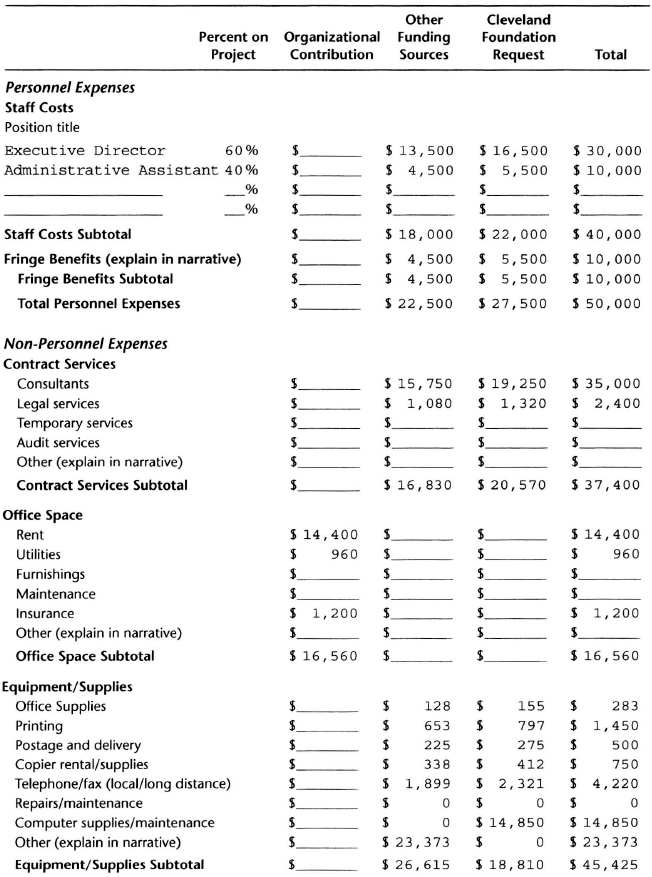

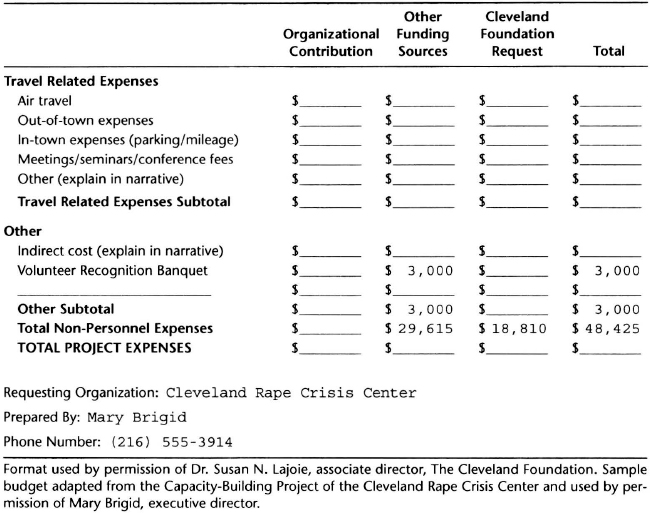

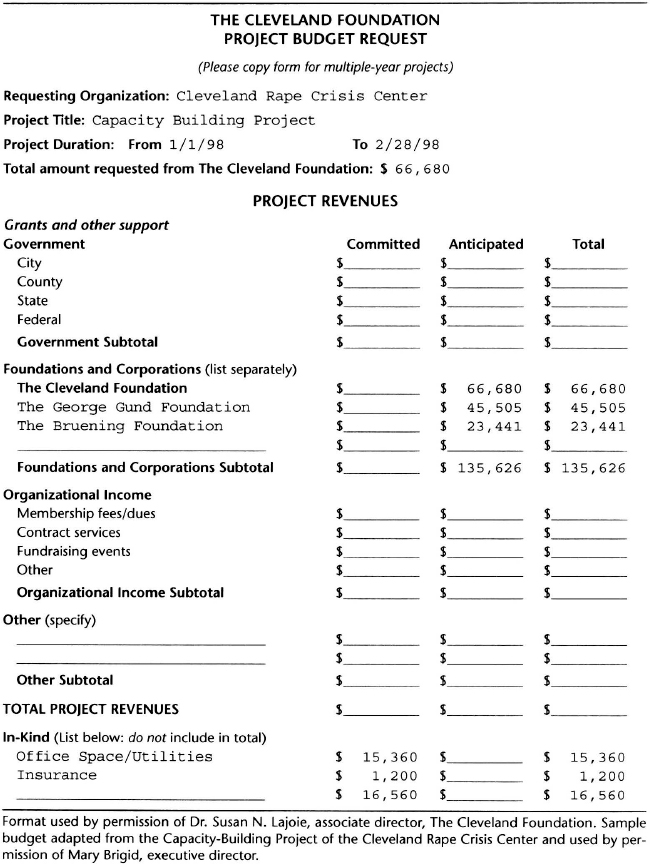

Expenses. Accounting convention requires that revenues be listed before expenses. In putting together a proposal budget, however, you need to calculate your expenses first so you can decide how much grant support to request. To do this, use a project expenses form such as that shown in Exhibit 7.2 to begin building your budget. This example has been filled in for a one-year period. If your project will last more than one year, copy the form and do each year separately. When all years have been completed, total them on another form to serve as a summary. As we review each section of Exhibit 7.2, guidelines will be suggested for developing both the line items and the narrative that must accompany the budget.

Personnel Expenses. In estimating the percentage of a person's time allocated to a project, it is usually easiest to think about how much time the individual will spend on a weekly basis and then multiply by fifty-two. For people who will be spending a major portion of their time on the project, you can base your calculations on a total of 2,080 paid work hours in the year.

EXHIBIT 7.2. PROJECT EXPENSES.

Consult your fiscal office to obtain information on fringe benefits. Be sure to ask what costs are covered, as these vary considerably from one organization to another, and even from one position to another.

Nonpersonnel Expenses. Contract services, especially consultants, can present problems in a review by a program officer. Because foundations generally base their own payments to consultants on the government rate, program officers who scrutinize your proposal may not be well informed about current market rates. You are well advised to contact a national organization in the consultant's field of expertise and request a written statement that documents the generally accepted market rates in the field. If you cannot obtain a written statement, at least discuss the matter with an objective third party and take some notes on what market rates are perceived to be. To determine a consulting fee, you will need either the consultant's estimated total fee, or an hourly or daily rate plus the consultant's estimate of the amount of time the job will require.

Your project may or may not involve other contract services. If it does, be sure to retain the worksheets in which your estimate was developed—hourly rate and number of hours—to review with your grantmaker during a meeting after the proposal is submitted.

Office Space. You may have given minimal thought to some line items, such as the cost of insurance or utilities. Wherever costs are unknown to you, work with your business office staff to do the research and estimate the numbers.

Equipment and Supplies. It's very difficult to forecast many of these line items. The best method is to prorate your organization's annual expenditures based on the relationship of your project to the rest of the organization's activities.

Travel and Related Expenses. Because so many scandals and abuses have involved the inappropriate use of grant, government, or nonprofit funds, this section will be very closely scrutinized. To make sure your budget holds up, be extra careful when estimating any travel expenses for which you are seeking support. Hotel and airline rates change frequently and sometimes dramatically; when you prepare your budget, you may not know where your professional meetings and conferences will be held two or three years later. Many large organizations book hotel space as far in advance as possible, but smaller organizations may not select a site for a meeting that far ahead. If that is the case:

- Review your actual travel costs for the past few years.

- Select a few representative meeting sites. Contact a travel agent to determine the current travel and hotel costs for these sites.

- Hope that the organization doesn't select a site that is much more distant or a hotel that is much more expensive.

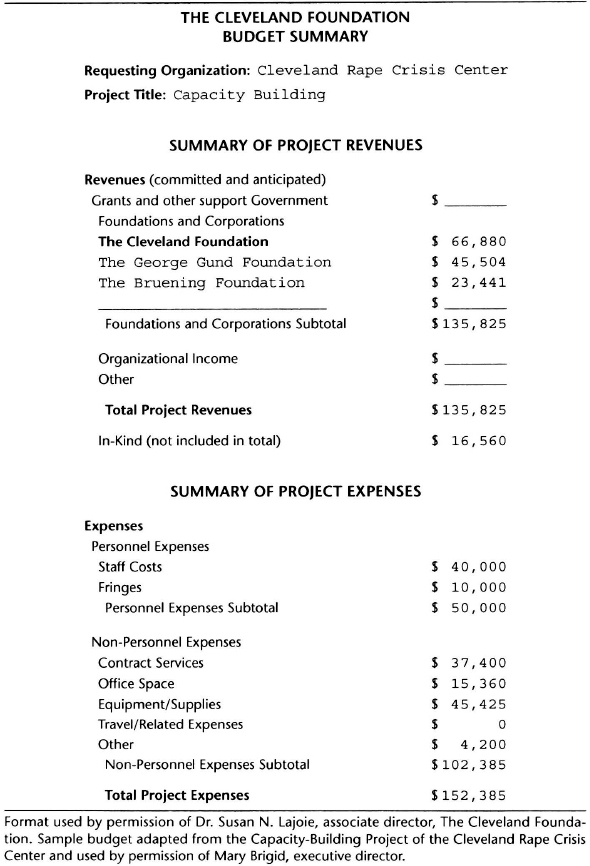

Revenues. When you have finished estimating your project expenses, you can move on to the next section of the budget: project revenues. In the Exhibit 7.3 example, the format requires you to distinguish between funds that are committed and those that are anticipated. Under “Committed Funds,” list only those grants for which you have a written, legally binding commitment. Organizational income may be challenging to forecast; you will usually be close if you review your organization's budget history and base your calculations on the trends of the past several years.

EXHIBIT 7.3. PROJECT REVENUES.

From the revenue section of your budget, you draw the information to use in the project budget request. For obvious reasons, most grantmakers are more interested in the funds you are requesting from them than the funds you are seeking elsewhere. Prior to any meeting or conversation with them regarding budgets, review your backup material; when you discuss the funds you are seeking from them, be prepared to discuss in detail the reasoning behind each line item.

With all this detail completed, you are now in a position to prepare a budget summary like the one in Exhibit 7.4. The numbers in a budget summary should be taken directly from the budget detail and be consistent throughout your budget sheets. If you use spreadsheet software to develop your budget, your numbers will be subject to rounding; be sure to review all sums manually so you can correct the effects of rounding, because you can be sure that your grantmaker will check your math manually. Any errors, even those produced by automatic rounding, can damage your credibility.

Budget Narrative. The grantmaker may suggest the level of detail grantseekers should include in the budget narrative. Following are two of The Cleveland Foundation's examples of detail about expenses for which funding is sought, one for a staff position and one for a nonpersonnel item.

Project director: This position is accountable for planning, organizing, and directing the implementation and operations of the project. Specific responsibilities include directing staff, orientation, training, and evaluation in accordance with department standards. The project director also directly supervises three case managers.

Postage: The total requested postage budget is $2,500. This includes mailing routine correspondence, as well as the community health assessment questionnaire. The questionnaire is an integral component of our activities in year one, as outlined on page 22 of our proposal. The total number of questionnaires to be mailed is 7,500, at a cost of $2,175. The $325 balance is for the mailing of routine correspondence.3

Task Four: Project Evaluation

By this time, you know more about your project than you probably ever cared to, and you are definitely in the home stretch. Now you need to flesh out the plan for evaluating your project, which will become Section Five of your completed proposal.

EXHIBIT 7.4. A BUDGET SUMMARY.

You must define the criteria for a successful project, explaining when and how you plan to measure your results, both short-term and long-term, and who will be responsible for the evaluation process. Whenever possible, try to use standard instruments to measure progress. If no one within your organization really understands project evaluation, consult an expert from a university in your area.

Task Five: Project Continuation

If you recall, at the outset you were encouraged to pursue discussions with future funders, beneficiaries of your services, and members of other key constituencies in order to incorporate their interests into your planning and proposal preparation process. And in developing your budget projections, you were encouraged to show progressively less dependence on external sources of funding over time.

To complete the task of preparing Section Four of your proposal, provide as much detail as you can on how you plan to continue the project after the termination of the grant. Refer to projected budget revenues and explain how each source of committed funds and anticipated funds will contribute to the ongoing support of the project. These may include increased support from your own donor base as well as any revenues generated by the project.

Task Six: Project Description

Strange as it may sound, this moment late in the process is truly the best time to develop your statement of need, which will become Section Two of your proposal describing in detail the problem you are hoping to solve or the issue you are planning to address. Here, you also explain your project's goals and objectives and provide other information you may have skipped over in your first pass. Show how your project goals relate to your organization's overall mission, purpose, and long-range plan.

Why formulate your goals and objectives after your timeline and budget? Because only then will you have thought through what you are really going to do! You will not be indulging in vague rhetoric, as so many grantseekers do, but making definite statements that can be fully supported by all the detailed information you developed in the course of completing the previous tasks. At this point, of course, your goals and objectives should clearly reflect the activities you are going to conduct, including evaluation of the project.

Final Steps

Once the proposal narrative and budget are completed, you can move on to the part of the package that, next to the budget, will get the most attention: the executive summary. You also need to prepare a cover letter and assemble letters of support, and it all has to be done by the deadline.

Executive Summary

Preparing this is one of the most challenging tasks a writer can be assigned. In a few hundred words you must summarize, in a coherent and persuasive fashion, the most important points you have made in the six sections of your proposal and give the reader the sense that your project deserves full attention and close consideration. Faced with this challenge, many grantseekers resort to vague generalizations; others struggle to include as many facts as possible. Neither is ideal. A better approach is to try to select those significant few facts that best support the major points you want to get across. Be sure to leave plenty of time to perform this task. As Pascal once noted: “The present letter is a very long one simply because I had no leisure to make it shorter.”4

Most grantmakers do specify a length limit for this section, and it should be strictly observed. Sometimes grantseekers succumb to the temptation to reduce the size of the type they are using in order to cram in more copy, rather than editing the contents ruthlessly. This is not a good idea. If a grantmaker has to squint to read it, your document will put her in a bad mood, and if she is in a bad mood, she will be more critical of your document, if she reads it at all. Picture her at 11 P.M. with a big stack of proposals before her. For your own best outcome, be considerate and never use smaller type than twelve-point!

Cover Letter

In your cover letter, you will have even less room for facts or persuasion. You can take a paragraph to describe the nature of your project, its cost, and the amount of the grant you are seeking, which should be mentioned as early as possible. In another paragraph, you can emphasize why you chose to approach this particular grantmaker, and mention the benefits to constituents that will be most important to the grantmaker.

The cover letter should be signed by the officials specified by the grantmaker, usually the chief executive officer and an officer of the board. If they have specific thoughts about the importance of your project, their perspective should be integrated into the letter. If someone else in your organization has had direct contact with the grantmaker, try to dream up a clever way to refer to this person so the grantmaker can identify more closely with your organization.

Letters of Support or Participation

You may be aware that many proposals include letters of support and that you need to secure them and include them before your proposal can be submitted. Your first inclination—especially if you work in a large organization—would be to approach the head of the department in which the grant is being sought, or the CEO of your organization. Although securing letters from these individuals is the easiest path, using such letters gives the grantmaker the wrong impression. At best, it makes your organization appear either self-serving or arrogant; at worst, it makes your organization appear as one in which cooperation and collaboration are so rare that cases of people working together merit documentation.

The people on whom you should concentrate, rather, are external partners in a collaborative project, or outside experts in your field.

The best way to secure good letters from people external to your organization is to follow the procedure we will outline here, a procedure which recognizes that it is unlikely that the people who head organizations and need to sign the letters will be able to draft them within your time constraints, which usually means within a day or two at most. Remember, no matter how enthusiastic they may be, your project is probably not nearly as important to them as it is to you. Also, you probably know your project much better than they do—which means that it is easier for you to draft a letter which is relevant to your project than it is for them.

To ensure that you receive the letters you need in a timely fashion, therefore, and that they are as accurate as possible, you can get what you need and enhance your relationships with colleagues in the process, if you follow these steps:

- Call the person whom you are asking to sign the letter. Explain that you would appreciate having a letter of support (or participation) for a project you are seeking to fund.

- To make it as easy as possible for her to comply with your request, offer to provide a draft of the letter.

- Once she indicates that she is willing to sign a letter, make arrangements to send her the draft. If you are sending the draft on a computer disk, make sure to inquire about compatibility of word processing software, and be sure you exchange accurate addresses to accommodate the requirements of the mode of transmission, whether it be the postal service, overnight delivery service, or electronic mail.

- Draft the letter as you would like it to read. Follow the same principles you applied in writing your proposal: keep it specific, and keep it short.

The point of going to such lengths is to make the preparation of the letter as easy as possible for the person who will be signing it. Ideally, as soon as she receives your draft, her secretary will merely print out the draft on her letterhead, have it signed, and send it back to you.

Sending the Proposal

When you have received all the letters from your collaborating partners or supporting organizations, add them to your proposal packet. At last, it is time to ship the proposal to the grantmaker! Just a few notes about this final step.

If the grantmaker is a government agency, your proposal absolutely, positively must arrive by the deadline specified. Bureaucrats are simply inflexible. If you get caught in a last-minute crunch, as most grantseekers do, be sure to take an additional step just in case the weather prevents your overnight carrier from delivering on time: different carriers have air hubs in different parts of the country, so send a duplicate package by a different carrier. At least one is almost certain to arrive on time. This is cheap insurance! Finally, be sure to mail copies of the completed proposal promptly to your collaborating partners, to help them feel good about your partnership. Also send a copy to your board president or chair.

Benefits of Preparing a Proposal

By keeping the proposal preparation process in its proper perspective—as an element that is necessary but not sufficient to win a grant award—you are in a position to judge when it is worthwhile to commit yourself to the hard work required to prepare a high-quality proposal.

You should also be prepared to approach this complex task in an efficient and effective manner. If you follow the steps outlined here, you accomplish much of the planning required to shape your project, in the process developing and refining many skills that will help you to become a more effective manager: allocating time and resources, collaborating with colleagues and others outside your organization, conducting research, planning, and budgeting. In all these ways, you and your organization benefit from the process of preparing a grant proposal. Most important, you greatly increase your chances of winning an award and advancing the work of your organization.

Bundles of writing materials should not be carried in excess of needs. Normally, two bundles per regiment, one per battalion, and one per company are permissible. The weight of each bundle should not exceed 40 kilograms.

MAO TSE-TUNG, BASIC TACTICS