CHAPTER FIVE

“SEND ME SOMETHING IN WRITING”: DOCUMENTS THAT GET RESULTS

A small notebook and pen or pencil for taking notes and for letters to the outside or communication with other guerrilla bands ought always to be a part of the guerrilla fighter's equipment.

CHE GUEVARA, GUERRILLA WARFARE

When a grantmaker insists on seeing something in writing before agreeing to meet with you, what you have is a classic case of conflicting goals. You're ready to start talking, to establish your relationship. She wants a quick way to screen serious, worthwhile grantseekers from those who may waste her time. Fortunately, you can turn this lemon into lemonade by adopting a different perspective.

Consider the grantmaker's position. In the early stages of the relationship, grantmakers may have all the control and power, but their situations are far from easy; they are inundated by requests for appointments from grantseekers and by proposals that must be reviewed. As noted in Chapter One, there are only a few thousand professionals working full-time for U.S. foundations but more than half a million nonprofit organizations competing for their attention and that of the busy individuals who volunteer in foundation work. Grantmaking professionals in the public sector are also swamped with requests for more meetings than there are hours in the day, and for several times more dollars than are available. All these people need some way to separate those who merit their attention from those who don't.

The dynamic in this situation is similar to that of a job seeker and a prospective employer in any field where job seekers are more plentiful than jobs. Just as employers will ask to see a résumé or curriculum vitae before interviewing a candidate, so many grantmakers will ask to see a preliminary document before meeting with you. And just as preparing a résumé can help clarify the significance of your past experience and articulate goals for your next position, preparing a preliminary document for a grantmaker can be an opportunity to consolidate your thinking and clarify key issues.

Planning Your Response

Keep in mind that this preliminary document, like a résumé or indeed any business document, may be necessary but it is not sufficient. Yes, you will need to prepare the document carefully. You will need to be cogent and persuasive. You will need to follow the prescribed format and content, present your document in a professional way, and submit it in a timely fashion. But all this will not be sufficient to secure a grant. A document is only part of the story—one element in a complex series of transactions in making a deal.

That said, the first order of business is to respond promptly to the grant-maker's request and to submit a document of high quality. Your goal should be to prepare as brief and cogent a document as possible.

Three Types of Documents

The first decision to be made is what kind of document you will provide. There are three basic types: the letter, the concept paper, and the white paper or position paper. Most often, the grantmaker will specify which one she wants, and you will comply. If she leaves it open, you can choose whichever serves you best.

Although a prompt submission is advantageous, you shouldn't let yourself be pressured into preparing your document too hastily. Time invested in planning and thinking through strategic issues will pay significant dividends in the quality of the relationship developed.

Key Elements of the Document

Whether or not you have the option of deciding which kind of document to prepare, these are the key elements to consider:

- Purpose; the desired outcome

- Role of the document in building the relationship between you and the grantmaker

- Structure

- Strategic content

- Voice or tone

The Letter

If the grantmaker doesn't specify which kind of document she wants, you should generally prepare a letter, as it is the least formal and the closest to a conversation. Remember, it is conversations and the building of relationships, not the submission of documents, that wins grants.

Purpose

The purpose of a letter, like that of an initial telephone conversation, is to establish or enhance your relationship with the grantmaker. You are seeking the same specific outcome: to persuade the grantmaker to meet with you. All other choices you make in developing the document should relate to this goal.

Role in the Relationship

You may have no choice but to comply with the grantmaker's request for a document, but you can still present yourself in it as a colleague rather than a prostrate supplicant. Concentrate on the challenges of developing the project and the longterm funding strategies—the “big picture.” If you emphasize your need to secure immediate grant support, you come off as a supplicant and an undesirable partner.

You can also influence the grantmaker's perception of you by seeking her advice; approach her as a resource, not as an obstacle between you and the grant. Doing so often succeeds for two reasons.

First, even if you are very sophisticated and knowledgeable, your thinking and planning can probably benefit from grantmaker input; grantmakers are often astute, thoughtful, and insightful people. They have much more experience than most grantseekers in observing a wide variety of projects, and they often have a keen sense of what will work and what will not. Many grant-funded projects reflect a cutting-edge approach, or even an experimental one. Grantmakers tend to develop a sixth sense about which kinds of experiments hold promise and which do not. Their perspective helps them to identify weaknesses in planning and to offer ideas that can strengthen a project.

Second, a frequent stumbling block encountered by grantseekers is the question grantmakers inevitably pose: “How do you intend to support this project after the grant support expires?” You may not have a ready answer when the project is conceived, but if you address the issue of long-term funding early on, you give yourself more time to develop sound strategies, increasing your project's odds of long-term success. The advantage of considering grantmakers as resource people is that with their experience in observing how projects progress from drawing board to full functioning, they can share with you long-term funding strategies that have been successful for similar projects. If you are the one to initiate the discussion of long-term funding, you demonstrate seriousness, impress the grantmaker, and increase your chances of securing an immediate grant.

Structure

The letter should follow this logical progression: background of the organization, background of the project, description of the problem or statement of need, description of the project, budget narrative, request for meeting, and budget summary. As you can see, this outline is similar to the one you used to plan your initial telephone conversation; actually, it can serve as the framework for virtually all communications with grantmakers, including concept papers and grant proposals.

Strategic Content

Your letter should provide enough information to convince the grantmaker that you have a full command of the situation and knowledge of the field, without overloading her with details. Remember, the letter is not a proposal; if you make it too detailed, the grantmaker may even consider it a proposal and evaluate it accordingly. This could bring your dialogue to a premature close.

Strategically, the most important part of your letter is the indication that, now that you have complied with the request for written communication, you will be calling to set up a meeting. By stating that you will make the call, you acknowledge the grantmaker's superior power, at least at this stage of the relationship. A typical closing sentence might be: “I will call within two weeks to set up a convenient time for us to meet and discuss these ideas.” Specify two or three weeks; that's enough time for the grantmaker to read your letter but not so much that she will have forgotten it when you call.

Voice

The voice or tone of your letter should be businesslike, but warmer and more personal than a proposal or concept paper. Make it seem like a conversation, rather than a summary of your annual report:

| Formal Document | Informal Expression in Letter |

| Background of the organization | “Here's who we are.” |

| Background of the project | “Here's our situation.” |

| Description of the problem | “Here's the problem (need) we've identified.” |

| Description of the project | “Here's an idea we have to solve the problem [meet the need].” |

The Concept Paper

A concept paper is a document that describes an idea you have for a project. If your grantmaker requests a concept paper, or you decide that preparing such a document is the most appropriate course of action, keep the following points in mind.

Purpose

A concept paper is intended to capture the interest and imagination of the grantmaker. Although a grant is never made on the basis of a concept paper alone, the document can certainly generate a desire to support your project; use it to convince the grantmaker to meet with you to explore in greater detail the potential of your idea.

Role in the Relationship

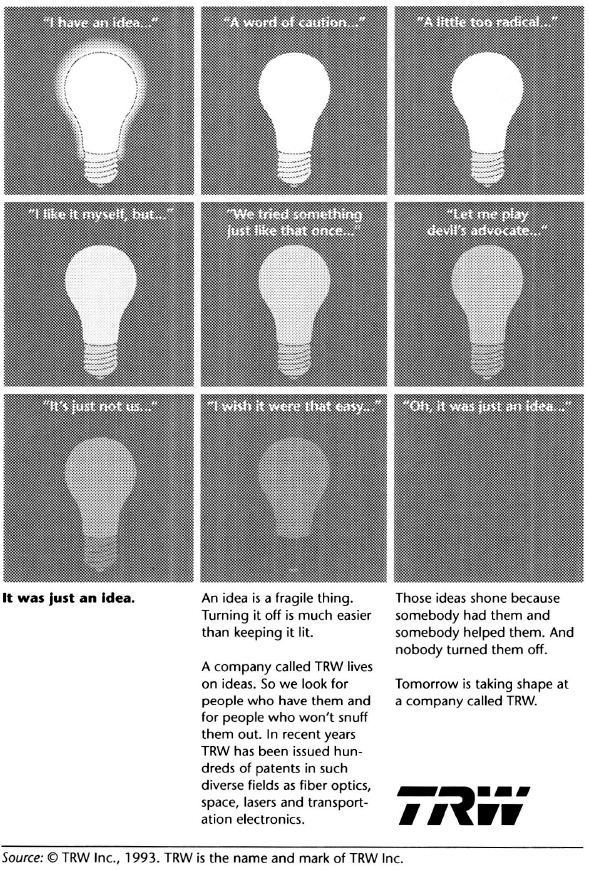

Because the purpose of a concept paper is to share an idea, submitting one implies a high level of trust, which is the cornerstone of a good working relationship. It demonstrates your confidence that the grantmaker will respect your ownership of the idea whether or not she supports it financially, and that she will not share it inappropriately with others. As the advertisement reproduced in Figure 5.1 demonstrates, ideas are not only the most valuable commodity in our culture, but the most fragile.

By sharing your concepts with grantmakers, you get them involved at a very early stage—and in the grantseeking enterprise, the sooner they are involved, the better.

Structure

The structure of the concept paper is similar to that of the letter. If you have already established a relationship with a grantmaker who knows something about your organization, you can cover the background very briefly and then move on to a discussion of the situation that prompted you to develop your idea.

Strategic Content

The concept paper is similar to an essay in which you run an idea up the flagpole to see who salutes; it is the most cerebral of preliminary documents. In it, emphasize why, rather than how, a project should be undertaken. Draw attention to the creative and innovative aspects of your approach and how it differs from others tried in the past.

FIGURE 5.1. AN IDEA IS A FRAGILE THING.

Voice

When novice grantseekers prepare documents, they often adopt a formal style whether it is called for or not. They use highly technical terms and language that is stilted and impersonal; their writing is characterized by a high level of abstraction and a preponderance of the passive voice. Such documents tend to sound as though they are written by one organization for another, rather than by one person for another person. But things don't get done by organizations, only by people. Shy individuals like to hide behind the protective mask of an organization; unfortunately, this creates distance between grantseeker and grantmaker, and distance rarely enhances a relationship.

Author William Mengerink suggests that grantseekers prepare all their documents as if they were writing a letter to Aunt Sylvia, a family member of whom they are fond.1 It's a good idea. Your grantmaker may not be quite as receptive as a relative who loves you, but will probably prefer to hear from a real person instead of an impersonal organization or office. Take the risk of being visible and identifiable as the person responsible for the conception of a project or the shaping of a plan or event. And whenever possible, make your concept more concrete by including vignettes about real people; these examples make it easier for the grantmaker to remember your project.

The White Paper

If your grantmaker requests a white paper (position paper), or you learn of an opportunity to submit one, then rejoice: your chances of success are excellent, because the process has been initiated by the grantmaker. As discussed in Chapter One, grant programs begin when a grantmaker decides to address a problem by investing money in it. Sometimes grantmakers realize that people in the field may have more expertise or knowledge of current developments than they do, and so decide to shape more meaningful programs by soliciting input from practitioners or researchers. When this occurs, one of two things may happen.

Grantmakers on a short timetable may go to their Rolodexes and call a few people, usually current or former grantees, and talk with them. If you are one of these people, you may not need this book, but few grantseekers achieve this stature. Beyond this casual networking approach, a grantmaker may request white papers. What makes this situation so promising for grantseekers? First, the grantmaker is taking the initiative; and second, communication is beginning at an early stage. In other situations, grantseekers are supplicants and all power is held by the grantmakers. But when grantseekers are solicited for white papers, they are being approached as colleagues who have information that the grantmakers need. In our society information is the most valuable currency, and when a grantmaker acknowledges that you, the grantseeker, possess this resource, it shifts the balance of power in the relationship.

Also, when the grant program is still being formulated you work with the grantmaker at the earliest possible stage. You can benefit in many ways from this early involvement. Just as a parent can shape a child's values and development, people involved in the formative stages of a project can influence how it develops; furthermore, early involvement provides more time for you and your grantmaker to become familiar and comfortable with one another. In grantmaking as in other enterprises, people are apt to do business with people they know rather than with strangers. So your early involvement will give you an advantage over competitors who enter the process at a later stage.

Purpose

Your goal should be to impress grantmakers by making them understand that you are a member of the new aristocracy of our information society—an “information overlord.” You want to show that your knowledge is both broad and deep, that your information is up-to-the-minute, and that your contacts include leaders in your field. If you succeed, you will achieve the desired outcome: the grantmaker will seek to continue the dialogue and eventually request a formal proposal.

Role in the Relationship

The preparation of a white paper presents a great opportunity to establish yourself in the eyes of the grantmaker as a most attractive potential business partner by demonstrating that you are both well informed and well connected. The white paper should also imply that you can make the grantmaker look good; if you can provide useful information and help her stand out among her peers and colleagues, you will earn a high degree of respect and gratitude.

This also puts you in good standing for subsequent interactions, including the preparation and submission of a proposal. In any relationship, you may be called upon to play several roles, but the first one usually makes the strongest impression; your initial role as a colleague and helper will influence a grantmaker's perception of you when you become a competitive grantseeker. Your proposal, of course, will be reviewed along with all the others, but many of these will be viewed as coming from supplicants.

Structure

Your white paper should include the following elements in the following order:

- Description of the issue or problem—its scope, size, shape, and dynamics

- Impact of the issue or problem

- Previous attempt(s) to address the issue or solve the problem

- Description of your new solution and why it holds greater promise than previous efforts

- Potential benefits of implementing your new solution

Strategic Content

Each of the above elements should be approached with your purpose clearly in mind. Because the grantmaker who solicits a white paper usually has a working knowledge of the issue or problem, your description of it can usually be covered briefly, but if you are not sure how much detail the grantmaker wants, you have a wonderful opportunity to open the dialogue by asking about it directly. In the course of your conversation, you can gain a lot of useful information about the program and the grantmaker's interests.

Take care in preparing the section on previous attempts to solve the problem and the one on the solution you propose, because the people who suggested previous solutions may be known to the grantmaker; she may even have supported some of their earlier work. For that matter, some of them are almost certainly preparing white papers to compete with yours. So show proper respect for the work that preceded your own by treading lightly in discussing previous efforts that failed or experienced only limited success.

Concentrate on the section that describes the potential benefits of implementing your proposed solution. This section has the greatest potential to persuade the grantmaker to support your project. Keep focused on your ultimate purpose: you are trying to get a grant, not preparing an academic treatise.

Voice

Because the white paper calls for a fairly high level of abstraction, it is tempting to adopt an academic tone and to write from a stance that is distant and aloof. But to make your submission memorable, include as many concrete examples and statistics as possible. These demonstrate your grasp of details and perhaps even of arcane data, which is bound to impress your grantmaker.

Before You Start to Write

Whether you're generating a letter, concept paper, or white paper, before you sit down to draft it, think through your strategy. The first step is to define your purpose and to outline the result you hope to achieve. Think about what interests the grantmaker and try to match your presentation to those interests.

Outline all the information you have available, and identify any gaps to be filled in. Try to identify the best sources for the information you lack. If your initial outline raises questions, write them down and figure out how they can best be answered, and by whom. As you begin to draft your document, try to answer these questions:

- Who will direct the project?

- Who will benefit from it?

- What activities will need to be carried out?

- Who will carry them out?

- What human and physical resources, and in what quantity, will be needed to carry out these activities?

- Where will these resources come from?

- What will they cost?

- How will you know when you have succeeded?

- How will the world be different once you have succeeded?

Answering these questions even in summary form may require a considerable investment of time and energy, so you will get the job done faster if several people gather the information. Once all of it has been assembled, select one person to write your document. Just as a symphony orchestra sounds better with a conductor in charge, your document will read better and make a stronger impression if it is written in one voice.

After your first telephone conversation and after you've submitted something in writing, if asked to do so, you are ready to prepare for your first meeting with the grantmaker.

The guerrilla . . . turns the hazards of the terrain to his advantage and makes an ally of tropic rains, heavy snow, intense heat, and freezing cold.

CHE GUEVARA, GUERRILLA WARFARE